Abstract

This paper proposes sustainable entrepreneurial orientation (SEO) as a multidimensional construct that offers researchers the possibility of empirically testing their theoretical proposals in the sustainable entrepreneurship field. The authors propose an integration of different theories. In accordance with the dynamic capabilities view, SEO is approached under an organizational paradigm of strategic orientations delimited by competitive culture and multiple orientation perspectives. Furthermore, SEO’s nature is conceived at a firm-based entrepreneurship level and is based on an integrated triple bottom line sustainability. This approach is conceptualized using a categorization scheme and defined in accordance with the organizational predisposition perspective. Several research lines are proposed, all based on relational models with SEO as the key concept.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship and sustainable development are not mutually exclusive [1]. We live in an international scenario in which governments foster both growth through entrepreneurship (e.g., Global Entrepreneurship Monitor) and achievement of sustainable development (e.g., UN Sustainable Development Goals), by creating tools for worldwide impact such as UN Global Compact to reconcile business interests with the demands of communities. Following from this, the pursuit of opportunities within the interplay of sustainability and entrepreneurship is presented as a major and ongoing challenge for organizations [2].

Society needs to manage its economic, social and natural capital, the depletion of which could be irreversible if steps are not taken [3], as stated in the Brundtland Report [4], which settled the guidelines for creating more sustainable business models. Along these lines, given that ecological and social problems were once largely attributed to the effects of entrepreneurship itself, there is an increasing line of thought that it can also minimize and eliminate the abovementioned negative consequences [5]. In the past, issues such as climate change, industrial toxins, water and air pollution or human rights abuses, were usually tackled by legislative, legitimizing, ethical or competitive initiatives. More recently however, incentives to do so are increasingly emerging from the perspective of entrepreneurship linked to the notion of sustainability [6].

Although entrepreneurs starting sustainable practices have existed since nineteenth century [7], it has not been until recent years that entrepreneurship for sustainable development has emerged as a debate topic of great interest in environmental management, business and entrepreneurship literature [8,9]. However, most contributions are just conceptual and theoretical. In this sense, there is a need for more theoretical research based on empirical models that provide these contributions with validity and reliability through their empirical testing [10].

From an organizational strategic orientation approach, the study of a strategic orientation for sustainable entrepreneurship is scarce and vague. Considering this, the paper aims to cover the following research gaps regarding the construct of sustainable entrepreneurial orientation (hereafter, SEO). As a first research gap, we consider that there is a lack of a clear conceptualization and operationalization of the SEO construct. A second research gap detected is the lack of relationship models including SEO antecedents and consequences.

Thus, the main purpose of this manuscript is to provide a theoretical proof of SEO as a business strategic orientation. We look forward to contributing to its conceptualization and definition and, therefore, to its consolidation as a construct of reference in sustainable entrepreneurship research.

This work seeks to enhance the value of the literature by combining different isolated theories in the conceptualization of the SEO construct. After undertaking an in-depth literature review, SEO is approached, in accordance with the dynamic capabilities view, within the organizational strategic orientations standpoint, following the competitive culture delimitation and multiple orientation perspective [11]. On this point, SEO is specifically defined from entrepreneurial orientation (EO) [12,13] and sustainability orientation (SO) [14] approaches. Consequently, SEO’s nature is conceived both at a firm-based entrepreneurship [15,16] and at an integrated triple bottom line sustainability level [17]. Regarding its conceptualization, SEO is approached through a categorization scheme and defined according to the organizational predisposition perspective [18].

Moreover, this paper proposes SEO as a construct that provides the basis for empirically testing the assertions that arise in sustainable entrepreneurship studies. Considering several contributions of researchers in the areas of entrepreneurship and sustainability at an organizational level, we propose some research questions for future proposals, all based on relational models with SEO as the key concept.

Regarding the structure, after a comprehensive review of the subarea of knowledge revolving around sustainable entrepreneurship, this paper continues with a review of SEO in the literature. This entails an examination of its conceptual description and contextualizes it within the dynamic capabilities approach. It then proposes a number of findings on the dimensionality of SEO to set up the foundations of its empirical validation. Finally, it concludes with several research lines revolving around the SEO concept.

2. Towards a Sustainable Entrepreneurship Framework: Contributions from Literature Research

In academic circles, there is consolidated recognition that sustainability issues are inextricably intertwined with the practice of entrepreneurship [19,20,21], but understanding of exactly how entrepreneurial organizations can develop the opportunities presented by sustainable development not covered in current markets is still at a very early stage [22,23].

Several authors suggest a focus on entrepreneurship from a sustainability point of view [8,24,25,26,27]. In this regard, the field of entrepreneurship can benefit from a more complete view of value creation by identifying opportunities, possibilities and impacts not only for the organization but also for other stakeholders and the society as a whole, in line with Cohen et al. [26]. These authors state that the pursuit of economic, social and environmental objectives is synergetic. Therefore, the usual economic stance taken when analyzing entrepreneurship at any level (individual, organizational or contextual) is not in itself sufficient to understand the holistic nature of entrepreneurial activity. As stated by Kuckertz and Wagner [8], entrepreneurial activities in general are related to sustainable development by promoting or impeding it, but in fact, only a few contribute positively to it. Thus, the aggregation of social and environmental dimensions to this economic dimension of entrepreneurship contributes to a maximization of global value [26].

Over the last decade a wave of scholarly works [9,22] has focused on sustainable entrepreneurship, as an important subarea of entrepreneurship [8]. In this vein, three main different research approaches can be distinguished between authors focused on an entrepreneurship that refers to entrepreneurial activities that positively contribute to sustainable development and the objectives derived thereof [8]. In this sense, sustainable entrepreneurship is the shortened term for entrepreneurship for sustainable development [8,21,28].

There exists an academic stream principally focused on the environmental aspect of sustainable entrepreneurship [29,30,31,32]. In the literature it is also known as environmental entrepreneurship [29,33], eco-preneurship [30], enviro-preneurship [34], green entrepreneurship [35], envirocapitalism [7] or green–green business [36]. Most authors following this environmental sustainable entrepreneurship approach define it at an individual level, emphasizing environmental entrepreneurs (or eco-preneurs or green entrepreneurs) instead of environmental entrepreneurial organizations [25,30,33]. As proposed by O’Neill and Gibbs [33] (p. 1731), “green entrepreneurs are those entrepreneurs who run businesses to achieve both environmental and business goals, and who wish to transform their sectors to be more sustainable”.

The literature on sustainable entrepreneurship has another line of research centered on the so-called social entrepreneurship, with contributions that focused primarily on the social aspect of sustainability (e.g., Prahalad and Hammond [37], Nicolls [38], Hall et al. [22], De Clercq and Voronov [20], Apetrei et al. [39], Ferreira et al. [40]); that is, on non-economic aspects of work, like social improvement and welfare [41]. According to Zahra et al. [42], this type of entrepreneurship refers to all activities and processes aimed at identifying and exploiting those opportunities that improve social wealth through the creation of social capital, social change or attention to social needs.

Considering these two approaches to sustainable entrepreneurship as either environmental or social entrepreneurship, some authors stand for a sustainable “double result” entrepreneurship; in other words, an entrepreneurship that only needs to combine two of the three dimensions (economic, social and/or environmental) to be considered as sustainable (e.g., Gerlach [43], Schaltegger and Wagner [44]).

Nevertheless, other works jointly integrate these social and environmental aspects [10,45] together with economic ones to qualify entrepreneurship as being sustainable [46,47]. This is with the purpose of achieving a complete and holistic perspective that complies with the three dimensions of sustainability, in accordance with the triple bottom line conceptualization by Elkington [48]. In Tilley and Young’s own words [49] (p. 87), “only those entrepreneurs that balance their efforts in contributing to the three areas of wealth generation can be truly called sustainability entrepreneurs”. Thus, it is not as much about sustainability as the intersection of three dimensions, but as an integration of them [17]. This paper adopts this approach in the understanding of sustainable entrepreneurship.

Regarding its definition, sustainable entrepreneurship is encompassed in literature in any of the following terms: innovative behavior [43], a continuing commitment [50], an examination [24], a process [28,51,52], an ability [53], a form of creation [44], a discovery and exploitation [10], a focus [46], a type of entrepreneurship [54] or a kind of entrepreneurial activities [8], as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

A literature review of the sustainable entrepreneurship definition.

A common aspect present among almost all the different definitions is the reference to opportunities, their examination, discovery, evaluation or perception and the dimensions of the sustainability triple bottom line. Although, in this latter case, some definitions only refer to two of the dimensions as necessary for sustainable development to take place (e.g., Gerlach [43], Schaltegger and Wagner [44]); this disagrees with the concept of sustainability adopted in our work. Thus, we reiterate that for sustainable entrepreneurship to occur, the presence of the three dimensions—economic, environmental and social—is essential. They are requisite for an organization’s entrepreneurial activities, in line with the contributions of Crals and Vereeck [50], O’Neill et al. [51], Schlange [17], Hockerts and Wüstenhagen [10], Shepherd and Patzelt [46] and Spence et al. [53], among other authors.

Additionally, sustainable entrepreneurship binds the process of entrepreneurship and opportunity recognition together [8], as shown in the distinct definitions provided. These opportunities are contemplated as sustainable entrepreneurship discovery opportunities (already present in existing economic structures) or sustainable entrepreneurship creation opportunities (that require the development of new economic institutions) [55]. They can be framed in Schumpeter’s [56] creative destruction concept, since sustainable entrepreneurial organizations can provide sustainable products, services, transport, processes or organizational structures that displace hitherto established companies with less- or non-sustainable practices [10,30,51,57]. It is usually the case for startups or small companies, given that large consolidated companies are often reluctant to change their business model. However, if they want to change it, they can transition to a more sustainable business model through innovation—process or product innovation [10]—and, therefore, through an entrepreneurship which actively fosters the introduction of processes and sustainable products in the organization.

3. The Convergence of Sustainability and Entrepreneurial Orientations from a Dynamic Capabilities View

In this path to an entrepreneurship for sustainable development, authors have settled their studies considering different theoretical approaches, as reflected in Table 2. For example, Hitt et al. [58] suggest that stakeholder theory can be used in order to foster a strategic entrepreneurship that achieve other types of benefits, such as natural and social benefits. Tilley and Young [49] relate sustainability and entrepreneurship under an ecological modernization theory, noting that this approach recognizes the structural character of current environmental issues. Thus, they propose that environmental issues are the promoters of industrial activity and economic growth and entrepreneurs are the promoters of sustainability. On the contrary, Pacheco et al. [55] consider sustainability as a ‘green prison’ for entrepreneurs. These authors explain their proposal under the game theory postulates, suggesting that only if entrepreneurs could influence the design of incentives in the competitive game, would the adoption of sustainable behaviors in organizations be worth it, not only at a collective level but also at an individual level. Regarding also the role of incentives, Meek et al. [59] highlight the influence of centralized and decentralized institutions in the implementation of incentives and regulations for an entrepreneurship focused on sustainable development goals, under an institutional theoretical perspective. From an integrated approach, Spence et al. [53] propose a combination of entrepreneurship, management and neo-institutional theories in the construction of a sustainable development theory. They suggest that sustainable entrepreneurship derives from the assumption of an interrelated scenario of individual, organizational and contextual factors.

Table 2.

Some related theories to the study of sustainability and entrepreneurship together.

However, according to an organizational strategic standpoint, the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities perspective have mainly served to provide the different authors with an explanation for the strategic integration of sustainability in the entrepreneurial mindset of organizations [60,63]. According to Hart [64], one of the main determinants of the development of capabilities in organizations comes from the restrictions of the biophysical environment. To this end, he proposes the natural-resource-based view to relate organizational competitive advantage with the natural environment, through the interconnection of the three strategies of pollution prevention, product stewardship and sustainable development.

Under the dynamic capabilities approach, Aragón-Correa and Sharma [60] consider for the first time environmental proactivity as a dynamic capability. They state that it is a socially complex, specific, dependent, non-replicable and inimitable strategy that goes beyond business environmental regulation. According to this proposal, other authors [61,65,66] also conceive environmental proactivity as a dynamic capability that allows organizations to adapt to the dynamism of their internal and external business environments. Similarly, some authors suggest that the dynamic capability for strategic change towards sustainability is a multidimensional construct involving exploration, identification and reconfiguration capabilities, as well as the interpretation of environmental issues as opportunities [60]. Therefore, dynamic capabilities allow organizations to reexamine their competitive strategies and thus achieve long-term growth while implementing their sustainable development strategy. Organizations can address environmental pressures that are often dynamic, complex and ambiguous [67] and then turn potential threats into competitive opportunities [63,68]. In this paper, we propose EO and SO as dynamic capabilities that together can foster sustainable entrepreneurship. Considering that EO is a strategic orientation that is resource-intensive and requires high investment [69], understanding its effects in terms of sustainability is an important research gap in the literature [47].

Boso et al. [70] propose EO as an internal strategic business capability that can stimulate the success of entrepreneurial firms in changing environments [71,72,73]. In addition, Zahra [74] indicates that entrepreneurship is important for creating and maintaining organizational internal ‘generative capability’. It is conceived as the capability for operational renewal that allows the creation of new capabilities. Both aspects reviewed by these authors coincide with the definition of dynamic capability. This work, therefore, follows the proposal initiated by these and other authors, conceptualizing EO as an organizational dynamic capability.

As a dynamic capability, EO is formed by a set of resources or capabilities that respond to the name of dimensions [66]. This dimensionality of EO has meant a theoretical division in the evolution of the construct in the literature, forming two main perspectives: one that follows the proposal of Miller [12], and one that prefers the proposal by Lumpkin and Dess [75]. We understand EO according to the tradition begun by Miller [12] and consolidated by Covin and Slevin [13], which determines that innovativeness, pro-activeness and risk-taking dimensions are a manifestation of firm entrepreneurial behavior. This approach to EO emphasizes the entrepreneurial process itself more than the role of top managers, thereby having important implications [76]. Besides, the three underlying EO dimensions put together enable firms to renew their organization, destroy market existing orders [77] and provide an alternative value proposition, which is potentially superior for the customer [78,79,80]. Innovativeness promotes knowledge acquisition through market information scanning and use, risk-taking provides a knowledge base from a focus on ‘trial and error’, and pro-activeness, as a looking-to-the-future perspective, increases market knowledge levels by pursuing new market opportunities [78,81].

As a strategic orientation, EO can be framed in the competitive culture perspective of Noble et al. [11]. This approach focuses on the importance of strategic orientation in organizational corporate culture as a business philosophy [82] that reflects the values of that culture [83]. Thus, EO encourages decision-making and specific behaviors, processes and practices that allow companies to create value by exploring and exploiting new emerging opportunities that offer future advantages (development of new goods, new productive methods, new markets, etc.) [16,69,75,78]. This work assumes this perspective in the EO study.

As mentioned before, the incorporation of sustainability into business strategy can therefore imply a competitive advantage based on intangible resources such as organizational culture and dynamic capabilities related to sustainability [84]. One such dynamic capability related to sustainability is SO, which like EO is a strategic orientation that, in this work, is framed in the perspective of competitive culture [11]. Thus, in line with Crittenden et al. [84], SO is conceived at a corporate culture level regarding a business philosophy that reflects the values of sustainable development [82,83].

As opposed to EO, SO as an organizational strategic posture has little presence in the literature, as it is a relatively recent interest among some authors, such as Corral-Verdugo et al. [85], Bos-Brouwers [14,86], Kuckertz and Wagner [8], Wagner and Maximilians [21], Eberhardt-Toth and Wasieleski [87], and Gagnon et al. [88]. SO is generally defined at the individual level [89]. However, in this research SO is a construct that is defined at the firm level and is rooted in business philosophy [65]. Paraphrasing Roxas and Coetzer [90], we refer to SO as the organizational strategic orientation toward the integration of sustainable interests and practices into strategic, tactical and operational activities. Thus, a company develops and demonstrates its orientation towards sustainability by integrating sustainable interests into its culture, decision-making, strategy and business operations and through its interactions with stakeholders [91]. Therefore, it is not only a matter of responding to customer needs, but of having an ideological commitment to sustainable development [84,92].

Regarding its conceptualization, we follow Bos-Brouwers’ proposal [14,86], seing SO as a unidimensional construct that can manifest itself in three different forms depending on how sustainability is perceived by the firm, as an opportunity, an obligation, or a cost, referring to the third, second or first phase of corporate sustainability [14,86,93]. Furthermore, according to these authors, SO includes the underlying factors of consciousness and motivation, which enable sustainability integration in the organization.

The meager academic studies exploring sustainable development from an EO perspective [22], indicate that while sustainable organizations usually have a high EO [53], the inclusion of sustainable development aspects in entrepreneurship entails greater risk, given its long-term perspective in measuring the outcomes of actions and recovering the investment. In this regard, knowing the sustainability orientation (SO) of an organization can help with the understanding of its entrepreneurial intentions to some extent, as conclude Kuckertz and Wagner [8]. Although these authors do not address SEO as such, they try to analyze the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and SO at an individual level, starting from entrepreneurship theory. To that end, they base their research in Dean and McMullen’s [25] sustainable entrepreneurship definition, considering that opportunities created by market imperfections to develop sustainable entrepreneurship can be made larger by adding SO to entrepreneurial intention models. SO is, therefore, considered as an antecedent of entrepreneurial intention. The authors’ explanation is based on the fact that individuals with SO are more likely to perceive entrepreneurial opportunities resulting from unsustainable economic behavior and to act in accordance with their social and environmental convictions. However, the results from their study suggest that this positive impact of SO tends to diminish or disappear with business experience. The more experience the organization has, the less influence SO has on the intentions for entrepreneurship [8]. Although these findings are consistent with organizational legitimacy and business ethics literature, they differ from other authors’ contributions, who indicate that business experience is an important qualification for the implementation of business models based on sustainable entrepreneurship opportunities [94].

Another contribution that empirically analyzes the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and SO is proposed by Wagner and Maximilians [21]. According to these authors, SO has a positive influence on the search for entrepreneurial opportunities related to sustainability, but not with entrepreneurial intentions, which are associated with entrepreneurial intent and direction. In short, for these scholars, what essentially drives entrepreneurship for sustainable development are entrepreneurial attitudes and not SO. Gawel [1] also examines the relationship between EO and sustainability, noting that while EO is part of the organizational culture and indicates a way of acting, sustainability is a set of principles and objectives. These social and environmental sustainability principles can be incorporated into the strategy and thus facilitate activities rebuilt by developing new products, new markets and new processes that provide measurable benefits to the organization. This author also proposes to measure the intensity of each of the dimensions of EO in relation to sustainability, reaching the following results: a high intensity in innovation and proactivity is related to the introduction of radical innovation in sustainable development issues, and a neutral intensity in risk taking promotes a strategy for a sustainable future. In this regard, Gawel [1] concludes that an organization’s involvement in sustainable development can be considered an entrepreneurial act.

Summarizing, Kuckertz and Wagner [8] and Wagner and Maximilians [21] studied the relationship between SO and one aspect of entrepreneurship, i.e., entrepreneurial intentions, and Gawel [1] focuses on the relationship between EO and sustainability. Even if those contributions are undoubtedly important in understanding the convergence of SO and EO, none of them specifically refers to their combination, or the nature of the relationship between them. Only Gagnon et al. [88] address, from the upper echelons perspective, the relationship between these strategic directions, jointly with market orientation, and their result in information processing and business performance. Gagnon et al. [88] note that EO and SO have a positive interactive effect on their relationship with information processing and that, while EO has a positive effect on performance, this is not the case for SO. Thus, in order to provide more insights on this topic, we propose that to follow the path of sustainability, organizations should draw from both EO and SO, converging into a single overall strategic orientation called SEO.

As such, SEO has not been extensively reflected in the academic literature. However, there are many terms related to a firm oriented to entrepreneurship and which includes sustainability in its managerial processes and practices, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

A literature review of terms related to SEO.

All these terms have in common a unique, holistic view of the business context, conceived with a long-term horizon and a commitment to responding to current and future stakeholders [60,62,88,101] according to SEO fundamentals. In this sense, sustainably- and entrepreneurially-oriented firms actively contribute—together with other organizations, institutions and public and private associations from economic, social and political circles—to sustainable development [102] as stated in the Brundtland Report [4].

On the contrary, some researchers emphasize several obstacles in relation to firms adopting SEO, such as unsustainable consumer behavior, arduous and complicated administrative and legal management [103] which can only be circumvented through incentives and substantial rewards [49,62], and resources and complex capability development such as technology, abilities, attitudes and top-level managerial conduct [60].

4. Results

4.1. SEO Construct: Nature and Contextualization from a Multiple Orientation Perspective

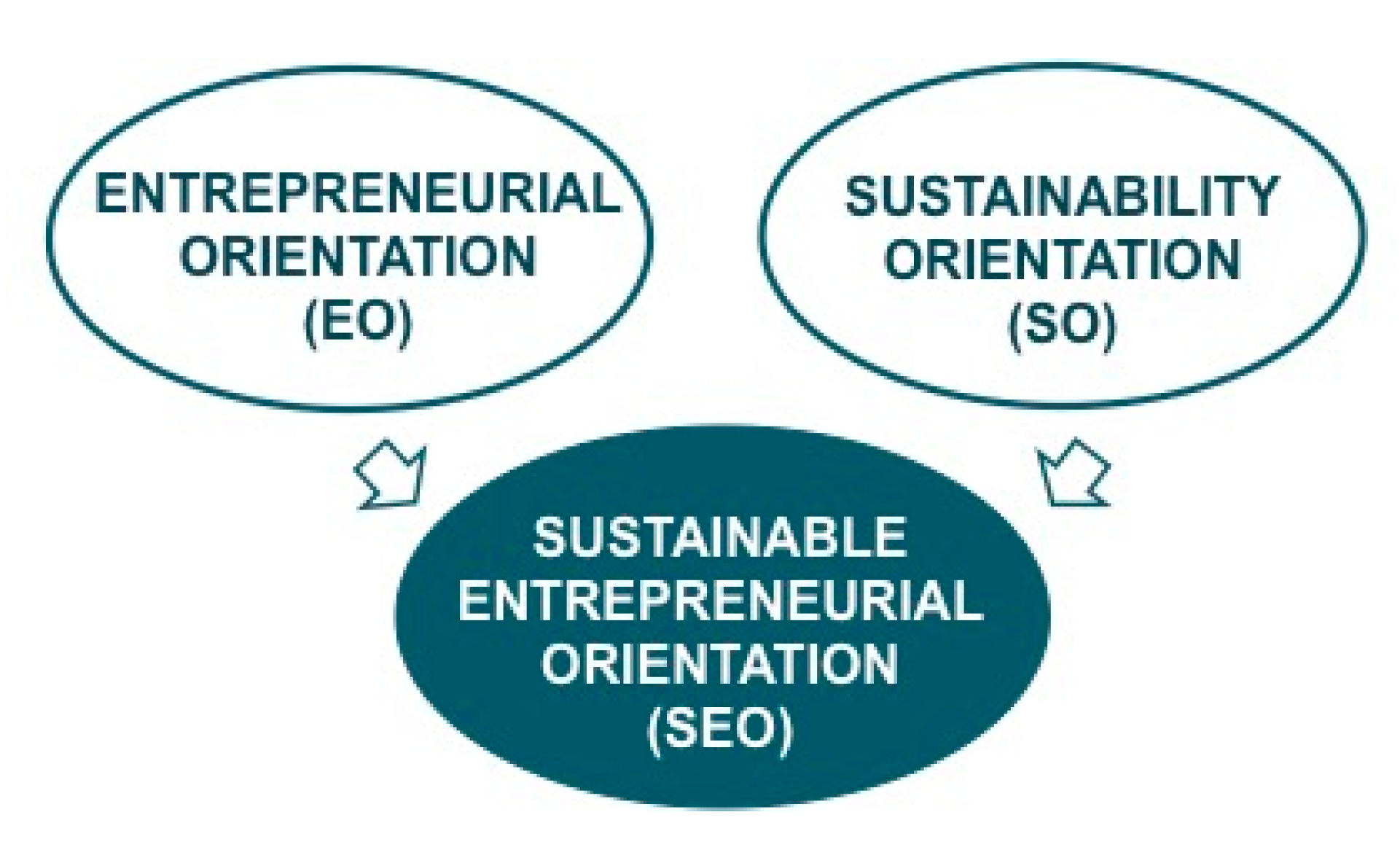

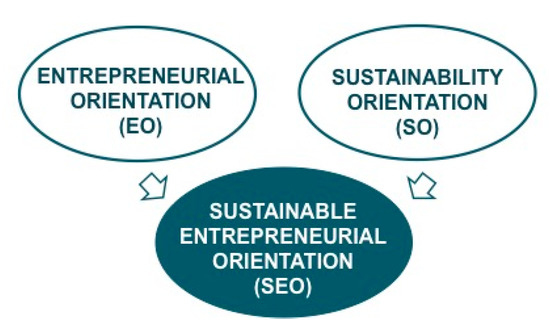

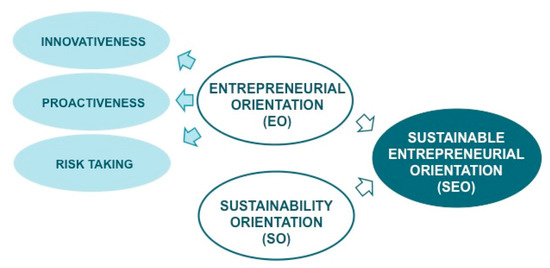

This paper follows the multiple orientation approach recommended by several authors [11,70,78,104,105,106], stressing the importance of companies adopting multiple orientations instead of solely one to avoid an undermining of responsiveness to the environment. Thus, we propose a configuration of the SEO construct as an integration of the two strategic orientations of EO and SO into the overall strategic orientation, as shown in Figure 1, in order to more effectively respond to the current environmental demands and instabilities through the combination of flexible adaptation and emerging opportunities discovery and exploitation capabilities. These approaches assist in the achievement of successful results at an economic, social and environmental level and, therefore, increase the chances of an organizations’ survival [48,84,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115].

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of SEO construct configuration.

Other studies that propose the construction of multiple strategic orientations are those by Covin and Miller [15], Mitchell [62], Zhou [81] and Frishammar and Andersson [116]. On the one hand, Mitchell [62] considers the creation of a sustainable market orientation as the integration of market orientation and sustainable development. As is asserted in our work, multiple strategic orientation configuration results from the combination of two constructs, EO and SO. On the other hand, Covin and Miller [15], Zhou [81] and Frishammar and Andersson [116] measure international entrepreneurial orientation as the relationship between EO and a dependent variable related to international performance. Contrary to these authors, in this paper SEO is not considered only as an organizational result but also as an important part of organizational culture reflected in business philosophy—both EO and SO are defined as organizational culture traits [84,111,112,113]. Thus, SEO performance outputs should be measured with a dependent variable which consider results at an economic, social and environmental level.

Among the proposed theories to address the integration of entrepreneurship and sustainability, the argument to adjust multiple orientations is supported within the logic of the dynamic capabilities approach, which states that superior performance can come from combinations of the strategic configuration, complementarity and existing business capabilities [117]. Thus, in accordance with Aragón-Correa and Sharma [60] and Menguc et al. [61], we conceive SEO as a dynamic capability, whose nature can be delimited in some of the classifications provided by the academic literature.

On the one hand, we propose SEO as a high-order capability, since it includes the ability to modify or create new first-order capabilities, as they can be EO and SO [118]. It is also identified as a renewing capability, since it modifies the resource base and allows opportunity identification and exploitation at an economic, social and environmental level [119]. Additionally, SEO is seen as an adaptive capability, since it refers to the strategic flexibility derived from the ability to explore and exploit emerging market opportunities in line with sustainable development [120,121]. Moreover, it can also be contemplated as an innovation capability, related to the ability to develop new products, productive methods, markets, supply sources and/or organizational forms, through a combination of strategic orientation and a set of innovative behaviors and processes—in this case, the combination of EO, formed by innovativeness, pro-activeness and risk-taking capabilities, and SO—to achieve organizational change behaviors consistent with sustainable development [77,122]. Finally, we conceive SEO as an externally-oriented capability, which tries to connect the rest of the organization’s capabilities by defining processes with the external environment, and, at the same time, allows the firm to compete more effectively in anticipating market requirements and establishing long-lasting and stable relationships with stakeholders [123].

On the other hand, according to Escribá-Esteve et al. [124], SEO is contemplated as an organizational overall strategic orientation. This is considered as a specific directional attitude that guides strategic planning and decision-making processes; moreover, this orientation should reflect several strategic orientations to successfully respond to context challenges. As well as EO and SO, SEO is a construct defined at the firm level, in accordance with proposals by other authors, such as Covin and Miller [15]. In this regard, Kuckertz and Wagner [8] note that application at an individual level can result in a reductionist view of the entrepreneurial phenomenon. Just as individuals develop habits of thought and action, organizations develop habitual response patterns [125]. This condition is known as organizational predisposition, which is inherent to any strategic orientation of the firm, and is the result of existing organizational rules and routines and organizational past performance [18]. In this case, organizational culture and values or core beliefs [69] play an important role in the organization’s adoption of sustainable entrepreneurial behavior as part and result of such a predisposition [126]. A firm with SEO is supported not only by the culture and internal organizational routines, but also by showing an EO, that is, innovativeness, pro-activeness and risk taking, in its commitment to—integrated, voluntary and formalized—managerial sustainable practices [53], consciously integrating interests towards sustainable development in decision-making, strategy, business operations and through their interactions with stakeholders [91]. In addition, SEO also shows an SO. Sustainability defined from the triple bottom line framework (i.e., economic, social and environmental dimensions) not only increases entrepreneurial firms’ opportunities for success [24] through the generation of sustainable competitive advantages coming from experimentation with new ideas, new products or new resources reconfigurations [65], but are also opportunities to create a more transparent, open and informative system for customers and other stakeholders [2]. In this respect, the success visibility of firms with SEO can increase other firms’ desire to incorporate such a strategic orientation, then further contributing to social cohesion and environmental protection [5].

In short, we propose that SEO is a high-order, adaptive, innovative and externally-oriented dynamic capability, which refers to an overall strategic orientation at the firm level [16] that shows an organizational predisposition to accept proactive, innovative and risk-taking processes, practices and behaviors [13,75,78] towards the achievement of sustainable development [28], through a conscious integration of either social and environmental issues in the business model [14,86] or the identification and exploitation of opportunities to produce economic prosperity, social cohesion and environmental protection [8,21].

4.2. SEO Categorization and Dimensionality

In line with the proposal by George and Marino [127] about the possibilities of EO conceived as a family of constructs rather than as a single construct, this paper extends this categorization scheme to include SEO, as one of constructs in the EO family, as these authors did with social entrepreneurship orientation. To explain its conceptualization, George and Marino [127] considered that Satori’s [128] conceptual development methodology was appropriate for the creation of concept categories with well-defined attributes depending on whether they are classic or radial categories. According to this classification, each categorization has a primary category (i.e., EO) and a secondary category (i.e., SEO) whose meaning is based in part on the main category. In classical categorization, a secondary category (i.e., SEO) contains all the elements of a primary category (i.e., EO’s innovativeness, pro-activeness and risk taking) plus additional components that make its unique (i.e., SO) with respect to other types of EO, such as international entrepreneurial orientation or social entrepreneurial orientation. This means that cases included in the secondary category are a contents subset of the primary category, i.e., movement from EO to SEO involves an increase in intension and a decrease in extension (implying more specificity and application to smaller cases). In the radial categorization, the secondary category contains some but not all components of the primary category (for example, an orientation to innovative entrepreneurship would contain EO’s innovativeness category, but not necessarily those of pro-activeness and risk taking). Therefore, taking classical modeling as a starting point, we consider SEO as a secondary category as reflected in Table 4.

Table 4.

Classical categorization schema of the SEO concept 1.

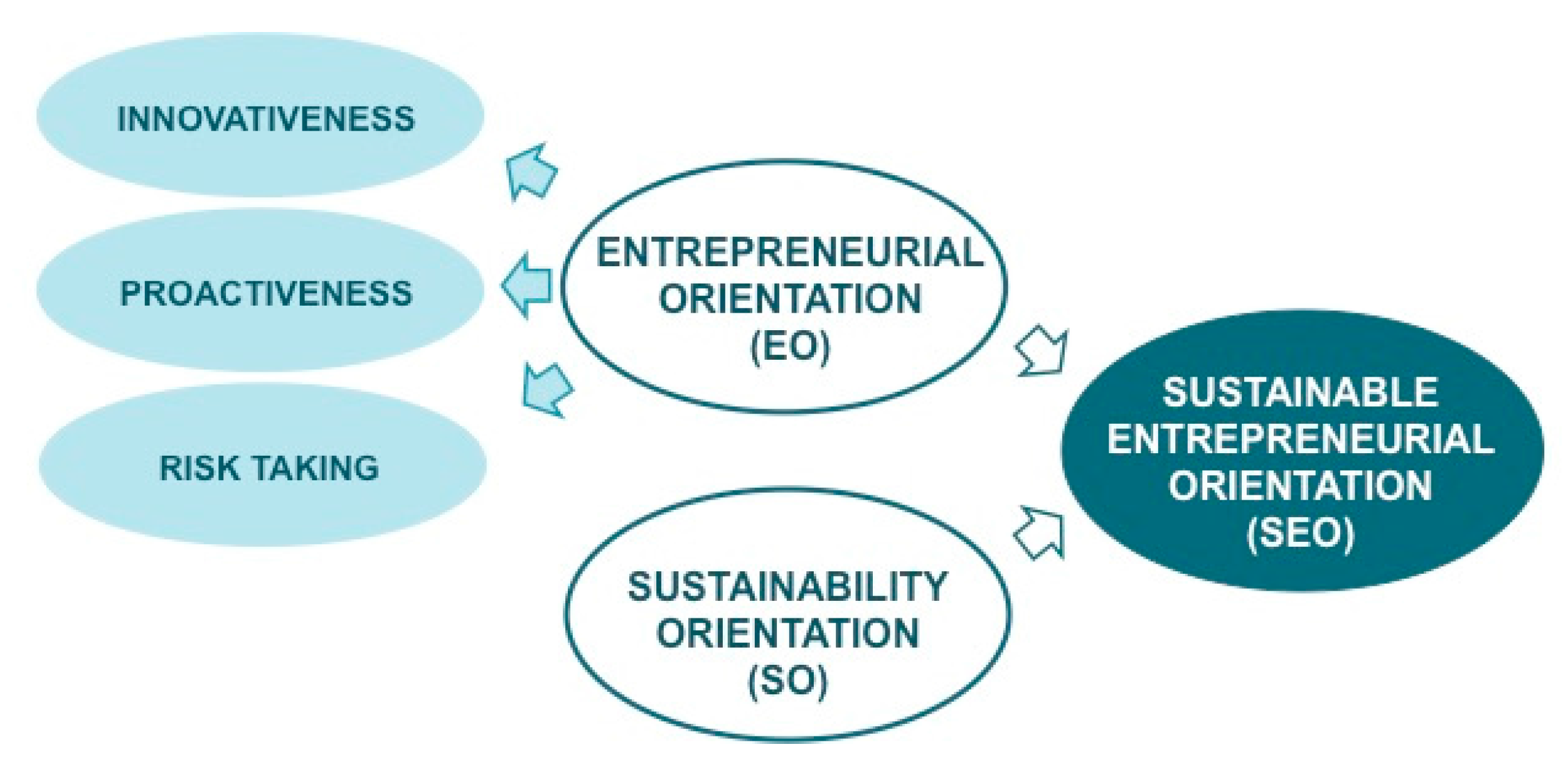

Concerning its dimensionality, this paper proposes that the dynamic capability of SEO is formed by SO and EO dynamic capabilities, the latter being, in turn, the combination of innovativeness, pro-activeness and risk-taking capabilities. SEO is therefore conceived as a third-order construct, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SEO dimensionality.

In sum, SEO has been defined in this research as a general higher order strategic orientation that functions as an umbrella term formed by the EO and SO subconstructs (hence a multiple strategic orientation). According to Cadogan [129], multiple strategic orientations are formative constructs by nature, since the variable dimensions of the formative strategic orientation can have their own nomological networks and, therefore, each dimension of the strategic orientation has the potential to have different consequences (i.e., EO and SO can have different results when evaluated independently). This means that these dimensions are combined to produce the construct [130]. Among different existing typologies of aggregate constructs (e.g., Edwards [130]), in this work SEO is thus considered as an aggregate construct, typified as reflective first-order, reflective second-order and formative third-order.

EO, as shown in the previous figure, is, in turn, a second-order construct of reflective first-order and reflective second-order [130], since each of its dimensions (innovativeness, risk-taking and pro-activeness) represents a different manifestation of the underlying concept, with relationships flowing from the construct to its dimensions. EO is thus measured according to numerous authors who estimate that their empirical measurement, even following the aggregate/composite/unidimensional current proposed by Miller [12] and Covin and Slevin [13], should be multidimensional and reflective in order to capture the essence of what the conceptual construct means [127,131], although other authors such as Dess et al. [132] believe that EO can be investigated as both a formative and a reflective construct. SO is considered a latent unidimensional reflective construct.

5. Discussion

Although SEO has not been treated as such in the literature, in the intersection of the two strategic orientations of EO and SO, there are distinct contributions in the academic literature. Spence et al. [53] points out that a sustainable firm has a high EO. The commitment to sustainable development principles can be understood as a proactive act [60,66] which generally leads to innovation [133]—also called sustainable innovation, green innovation or eco-innovation [14,134]—encouraging an organization’s adoption and integration of sustainability-oriented practices. This sustainable entrepreneurship entails risk taking, given the long period in which the scope and return of actions undertaken are projected [53,135]. However, in this regard, there is no consensus among academics. While Rodgers [95] found that firms with SEO have a risk tolerance over any other entrepreneurial firm, Spence et al. [53] and Gawel [1] indicate that risk taking exists but is calculated and limited, and Lumpkin et al. [41] argue that, in this type of firm, risks tend to be avoided. In any case, as stressed by Murillo-Luna et al. [136], a proactive strategy towards sustainable development involves the implementation of new processes, technologies and systems, and this always carries a certain risk due to the uncertainty of its eventual impact on organizational performance. The lack of agreement in this regard signals that further research is required to determine the role of sustainable entrepreneurship at the strategic business level.

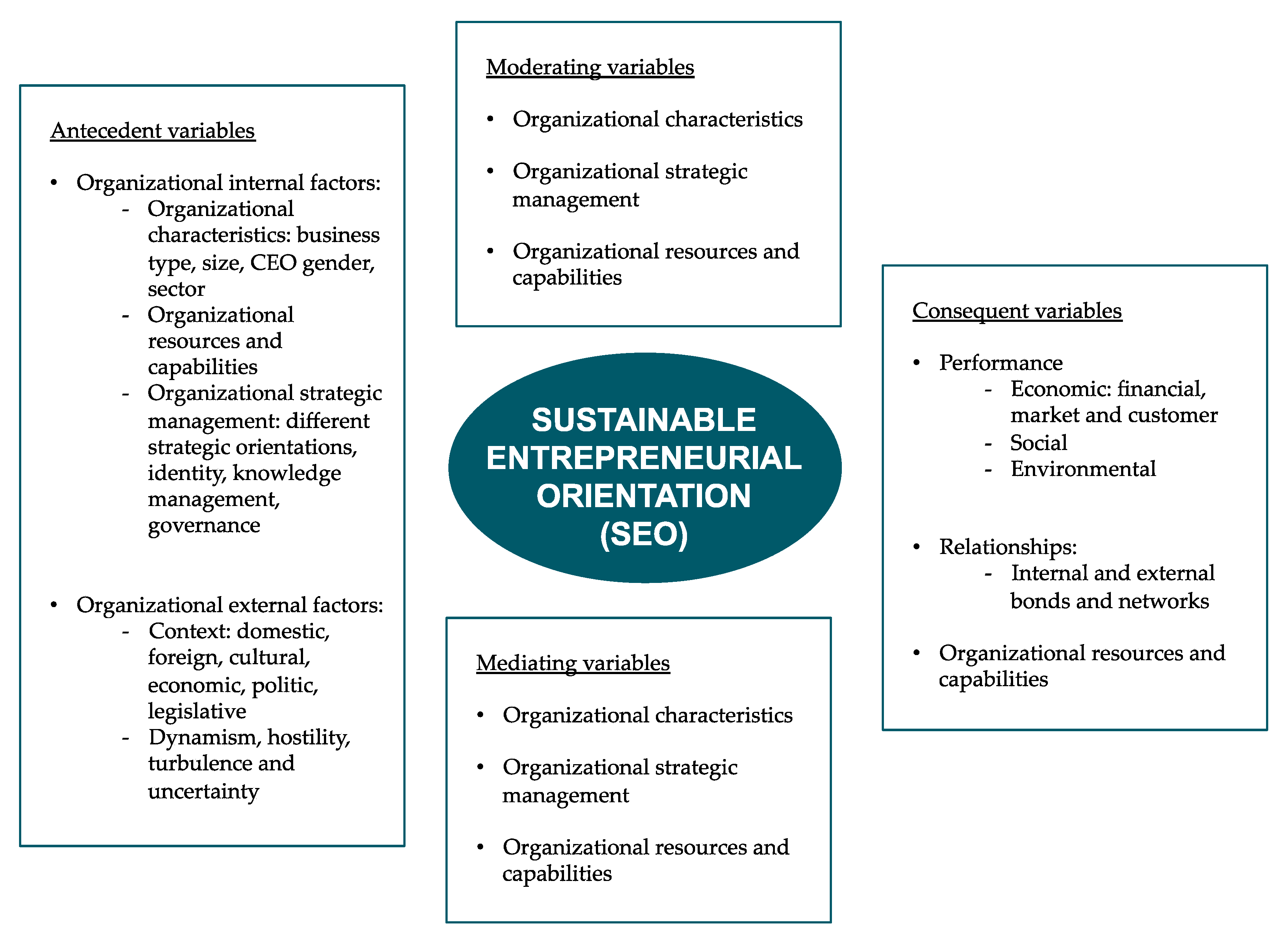

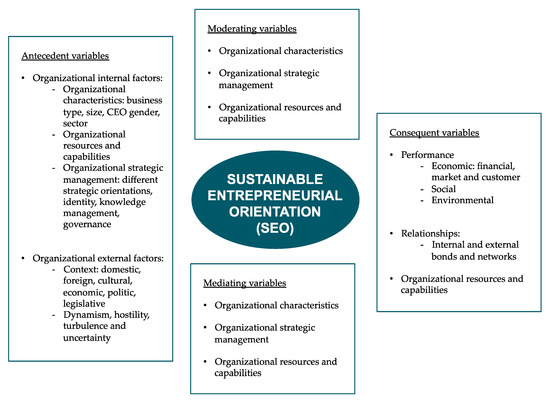

From the literature on strategic management, business, marketing, entrepreneurship, organization, strategy, business ethics, and sustainability, on the whole it can be gauged that EO and SO have been approached with antecedent, moderating, mediating and consequent variables in order to understand the role of these strategic orientations in the dynamic and changing environment of organizations. Since SEO is considered as a general high-order strategic orientation, researchers have the opportunity to test its relationship with the variables that allow them to be better familiarized with organizational behavior in a specific environment and in consideration of variables previously used in literature. Besides theoretical approaches to sustainable entrepreneurship, there is a need for more contributions based on empirical models that provide validity and reliability for these conceptual proposals. We offer a proposal of variables for empirical testing research in sustainable entrepreneurship with SEO as the key concept (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A proposal of variables for further research on SEO.

There are some research questions that arise from the literature that could be approached through this model.

- ●

- What effects do company size, age or sector have on the adoption of a SEO? How does CEO gender affect the relationship between SEO and performance? Is it possible to adopt SEO once you are established or it is only possible for startup companies?

- ●

- Is social capital an antecedent or a consequence of SEO? How do they relate with stakeholder engagement? How can SEO create value for different stakeholders? What is the effect of cultural context on SEO?

- ●

- What is the role of different organizational resources and capabilities in fostering SEO? Is SEO an antecedent that creates other resources and capabilities?

- ●

- What is the relationship between SEO and other strategic orientations? How do they behave in an international context?

6. Conclusions

Companies can undertake entrepreneurial ventures incorporating sustainability into their strategy in response to the uncertain nature of the environment in which they operate [137] and thus adapt their strategic orientation accordingly [138,139]. However, the versatility of today’s markets implies that organizations must build their strategy according to multiple strategic orientations, instead of solely one [11,70,78,104,105,106]. They should constitute an overall strategic orientation that collects the different strategic orientations within the organization [140]. In this work, we proposed that organizations should draw on both an EO and an SO, converging these into a single overall strategic orientation called SEO.

A review of the literature in the field establishes that there are three main approaches between authors in understanding sustainable entrepreneurship: environmental, social and integrated sustainable entrepreneurship. In this paper we adopted the latter approach, considering sustainable entrepreneurship from a holistic perspective that integrates the three dimensions of sustainability.

In this regard, this paper contributes to expanding the theory of dynamic capabilities from a strategic orientation approach, as both EO and SO are considered dynamic capabilities that enable organizational adaptation and renewal towards sustainable development at the corporate culture level, as stated in the competitive culture approach by Noble et al. [11].

The few studies focused on the study of the relationship between these two strategic orientations (i.e., EO and SO), have explained neither the nature of their relationship nor their combination. To this purpose, we propose an SEO construct. As such, SEO has scarcely been approached in the literature, even if there are some terms related to a firm’s orientation towards the inclusion of sustainability and entrepreneurship into business processes. Thus, we propose SEO from a multiple strategic approach as a construct integrated by EO and SO strategic orientations. In turn, we define SEO as a high-order dynamic capability that has the possibility of creating new first-order capabilities, such as EO and SO. SEO is also identified by being an adaptive, innovative and externally-oriented capability that refers to the organizational predisposition to accept proactive, innovative and risk-taking processes, practices and behaviors towards sustainable development achievement. According to the categorization proposed by George and Marino [127], SEO is conceived as a construct that belongs to the family of EO. Regarding its dimensionality, SEO is a formative third-order construct, formed by the reflective constructs of EO and SO. In turn, EO is a reflective second-order construct with a reflective first-order of innovativeness, pro-activeness and risk-taking dimensions. SO is a latent unidimensional reflective construct. Additionally, this paper proposes some research questions on the relationship models of antecedents, interactions and consequences with SEO as a key concept that provides researchers with both future research lines and the foundations to empirically test their proposals around sustainable entrepreneurship.

Therefore, this work provides some useful insights to enhance the existing gaps in the literature regarding the construct of SEO. In sum, we provided a contextualization and conceptualization of the SEO construct contributing to its theoretical consolidation in the literature. Moreover, we developed a proposal of SEO operationalization as a multidimensional construct for its empirical testing in future research. To that end, this paper suggests some research questions based on relationship models that include SEO antecedents and consequences. Ultimately, this work contributes to the study of the sustainable entrepreneurship knowledge area from a level of analysis that implies different theoretical approaches and to a basis for the empirical testing scholars’ research proposals focusing on this topic. As Shepherd and Patzelt [9] argue, it is necessary to work on the delimitation of sustainable entrepreneurship with a diversity of contributions that will undoubtedly benefit its consolidation.

From a managerial viewpoint, the pressure for organizations to adopt measures according to sustainable development principles can be minimized by promoting SEO as a strategic asset that allows companies to integrate economic, environmental and social objectives into their corporate culture. Organizations with an SEO are identified as being creative in both problem resolution and the implementation of new market strategies, even if these initiatives can entail some calculated risks. This kind of firm is constantly seeking changes in order to be ahead and leverage new opportunities. They do not see uncertainty as a threat but as a favorable opportunity. They are conscious of and motivated towards sustainability as an important part of their culture. Sustainability is an investment, a duty and an opportunity to grow and remain in the long-run. Moreover, it should be noted that SEO is everywhere in such an organization, in each member, each process, each technique, and each product or service.

Regarding the limitations of this study, they are mainly due to the inherent choice of different theoretical approaches. According to this, further research around the SEO concept and measurement could elucidate more understanding of the better perspectives to employ in its study and SEO behavior as an antecedent or consequence in regard to other strategic constructs.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the support given by the university chair Cátedra Ciudad de Valencia 2013, the InnDEA Foundation of the Valencian local government, and the University of Valencia for their research funding.

Author Contributions

A.C.-G., A.C.-T. and M.-A.I.-B. have equally contributed to the work in this research. This paper is part of a research project directed by A.C.-T.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

References

- Gawel, A. Entrepreneurship and sustainability: Do they have anything in common? Poznán Univ. Econ. Rev. 2012, 12, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.P.; Munilla, L.S.; Darroch, J. Sustainable corporate entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 5, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; ISBN 019282080X. [Google Scholar]

- López-Puga, J. Modelos actitudinales y emprendimiento sostenible. Cuides 2012, 8, 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- York, J.G.; Venkataraman, S. The entrepreneur-environment nexus: Uncertainty, innovation, and allocation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.L.; Leal, D.R. Enviro-Capitalists: Doing Good While Doing Well; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-8476-8382-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. Researching Entrepreneurships’ Role in Sustainable Development. In Trailblazing in Entrepreneurship; Palgrave MacMillan: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 149–179. ISBN 978-3-319-48701-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hockerts, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids—Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, C.; Sinha, R.K.; Kumar, A. Market orientation and alternative strategic orientations: A longitudinal assessment of performance implications. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Brouwers, H.E.J. Corporate Sustainability and Innovation in SMEs: Evidence of Themes and Activities in Practice. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Miller, D. International entrepreneurial orientation: Conceptual considerations, research themes, measurement issues, and future research directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, A.; Kubea, H.; Schmidt, S.; Flatten, C. Entrepreneurial orientation in turbulent environments: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1353–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlange, L.E. Stakeholder identification in sustainability entrepreneurship. The role of managerial and organisational cognition. Greener Manag. Int. 2006, 55, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmos, D.P.; Duchon, D.; McDaniel, R.R. Participation in strategic decision making: The role of organizational predisposition and issue interpretation. Decis. Sci. 1998, 29, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobers, P.; Rolf, W. Competing with ‘soft’ issues -from managing the environment to sustainable business strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2000, 9, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Voronov, M. Sustainability in entrepreneurship: A tale of two logics. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Maximilians, J. Ventures for the public good and entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis of sustainability orientation as a determining factor. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2012, 25, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltz, F.M.; Binder, J.K. Sustainable entrepreneurship: A convergent process model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Smith, B.; Mitchell, R. Toward a sustainable conceptualization of dependent variables in entrepreneurship research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stål, H.I.; Bonnedahl, K. Conceptualizing strong sustainable entrepreneurship. Small Enterp. Res. 2016, 23, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikis, I.N.; Kyrgidou, L.P. The concept of sustainable entrepreneurship: A conceptual framework and empirical analysis. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S. A framework for ecopreneurship: Leading bioneers and environmental managers to ecopreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 2002, 38, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, D. Sustainability Entrepreneurs, Ecopreneurs and the Development of a Sustainable Economy. Greener Manag. Int. 2009, 55, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staber, U. An ecological perspective on entrepreneurship in industrial districts. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1997, 24, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnanen, L. An insider’s experience with environmental entrepreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 2002, 38, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O′Neill, K.; Gibbs, D. Rethinking Green Entrepreneurship—Fluid Narratives of the Green Economy. Environ. Plan. A 2016, 48, 1727–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Menon, A. Enviropreneurial marketing strategy: The emergence of corporate environmentalism as marketing strategy. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubisi, N.O.; Nair, S.R. Green Entrepreneurship (GE) and Green Value Added (GVA): A conceptual framework. Int. J. Entrep. 2009, 13, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Isaak, R. Globalisation and green entrepreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 1997, 18, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hammond, A. Serving the world’s poor, profitably. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nicolls, A. Social Entrepreneurship—New Models of Sustainable Social Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; ISBN 0199283877. [Google Scholar]

- Apetrei, A.; Ribeiro, D.; Roig, S.; Tur, A.M. El Emprendedor Social-Una Explicación Intercultural. Available online: http://www.ciriec-revistaeconomia.es/banco/CIRIEC_7802_Apetrei_et_al.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2017).

- Ferreira, J.J.; Fernandes, C.I.; Peres-Ortiz, M.; Alves, H. Conceptualizing social entrepreneurship: Perspectives from the literature. Int. Rev. Public Non-Profit Market. 2017, 14, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Moss, T.W.; Gras, D.M.; Kato, S.; Amezcua, A.S. Entrepreneurial processes in social contexts: Hoy are they different, if at all? Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, A. Sustainable entrepreneurship and innovation. In Proceedings of the Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management Conference, Leeds, UK, 29–30 June 2003; pp. 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Innovation: Categories and Interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, B.D. Sustainability-driven entrepreneurship: Principles of organization design. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: studying entrepreneurial action linking ‘what is to be sustained’ with ‘what is to be developed’. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsohn, D.; Brundin, E. Beyond “shades of green”: Opportunities for a renewed conceptualisation of entrepreneurial sustainability in SMEs: A literature review. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual ICSB World Conference: Back to the future: Changes in Perspectives of Global Entrepreneurship & Innovation, Stockholm, Sweden, 15–18 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, F.; Young, W. Sustainability entrepreneurs. Could they be the true wealth generators of the future? Greener Manag. Int. 2009, 55, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Crals, E.; Vereeck, L. The affordability of sustainable entrepreneurship certification for SMEs. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World. 2005, 12, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, G.D.; Hershauer, J.C.; Golden, J.S. The cultural context of sustainability entrepreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 2006, 55, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labelle, F.; St-Jean, E.; Dutot, V. Déterminants de l’entrepreneuriat durable: Quelques constats auprès d′étudiants universitaires. LaRSG 2012, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M.; Gherib, J.B.B.; Biwolé, V.O. Sustainable entrepreneurship: Is entrepreneurial will enough? A north-south comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 335–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, R.; Dobes, V. An integrated approach towards sustainable entrepreneurship—Experience from the TEST project in transitional economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1807–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.F.; Dean, T.J.; Payne, D.S. Escaping the green prison: Entrepreneurship and the creation of opportunities for sustainable development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Harper and Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1942; ISBN 0061561614. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.; Wagner, M. Editorial: The Challenges and Opportunities of Sustainable Development for Entrepreneurship and Small Business. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2012, 25, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Sirmon, D.G.; Trahms, C.A. Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating value for individuals, organizations and society. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, W.R.; Pacheco, D.F.; York, J.G. The impact of social norms on entrepreneurial action: Evidence from the environmental entrepreneurship context. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Sharma, S. A contingent resource-based view of proactive corporate environmental strategy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S.; Ozanne, L. The interactive effect of internal and external factors on a proactive environmental strategy and its influence on a firm’s performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.W. Sustainable Market Orientation: Its Applicability in Conservation and Tourism Management. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schrettle, S.; Hinz, A.; Scherrer-Rathje, M.; Friedli, T. Turning sustainability into action: Explaining firms’ sustainability efforts and their impact on firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Matute, J.; Melero, I. El aprendizaje y la innovación como determinantes del desarrollo de una capacidad de gestión medioambiental proactiva. Cuademos Economia Direccion Empresa 2013, 16, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; García-Morales, V.J.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E. Un Modelo Explicativo de las Estrategias Medioambientales Avanzadas para Pequeñas y Medianas Empresas y su Influencia en los Resultados. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/807/80717237002.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2017).

- Bowen, F.; Sharma, S. Resourcing corporate environmental strategy: Behavioral and resource-based perspectives. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Rueda, A. The contingent influence of organizational capabilities on proactive environmental strategy in the service sector: An analysis of North American and European ski resorts. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2007, 24, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrep. Theory. Pract. 1991, 16, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Boso, N.; Story, V.M.; Cadogan, J.W. Entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation, network ties, and performance: Study of entrepreneurial firms in a developing economy. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 708–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, K.; Pennings, J.M. Internal capabilities, external networks and performance: A study on technology-based ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 615–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S. The asymmetric moderating role of market orientation on the ambidexterity-firm performance relationship for prospectors and defenders. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Ireland, R.D. Strategic entrepreneurship within family-controlled firms: Opportunities and challenges. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2010, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. Entrepreneurial risk taking in family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2005, 18, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J. The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation—Performance Relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 56, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economics Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1934; ISBN 0878556982. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno, K.; Mentzer, J.T.; Ozsomer, A. The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and market orientation on business performance. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpandé, R.; Farley, J.U.; Webster, F.E., Jr. Corporate culture, customer orientation and innovativeness in Japanese firms: A quadrad analysis. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market orientation and the learning organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and foreign market knowledge on early internationalization. J. World Bus. 2007, 42, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrat, K.; Shoham, A. The interaction between environment and strategic orientation in born globals’ choice of entry mode. Int. Mark. Rev. 2013, 30, 536–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, G.T.; Wert-Gray, S. Marketing entrepreneurship: Linking alertness to entrepreneurial opportunities with strategic orientations. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2012, 6, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden, V.L.; Crittenden, W.F.; Ferrell, L.K.; Ferrell, O.C.; Pinney, C.C. Market-oriented sustainability: A conceptual framework and propositions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Bonnes, M.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Frías-Armenta, M.; Carrus, G. Correlates of pro-sustainability orientation: The affinity towards diversity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Brouwers, H.E.J. Sustainable Innovation Processes within Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Ph.D. Thesis, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt-Toth, E.; Wasieleski, D.M. A cognitive elaboration model of sustainability decision making: Investigating financial managers’ orientation toward environmental issues. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.A.; Michael, J.H.; Elser, N.; Gyory, C. Seeing green in several ways: The interplay of entrepreneurial, sustainable and market orientations on executive scanning and small business performance. J. Market. Dev. Compet. 2013, 7, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Parboteeah, K.P.; Addae, H.M.; Cullen, J.B. Propensity to support sustainability initiatives: A cross-national model. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B.; Coetzer, A. Institutional environment, managerial attitudes and environmental sustainability orientation of small firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, C.; Goebel, P.; Foerstl, K. The impact of stakeholder orientation os sustainability and cost prevalence in supplier selection decisions. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2012, 18, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N.; Reichel, A.; Shani, A. Ecological orientation of tourists: An empirical investigation. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2007, 7, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keijzers, G. The transition to the sustainable enterprise. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, D. The process of entrepreneurial learning: A conceptual framework. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, C. Sustainable entrepreneurship in SMEs: A case study analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, P.D.; Polonsky, M.J. Environmental commitment: A basis for environmental entrepreneurship? J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1998, 11, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorne, F.T. Macro-entrepreneurship and sustainable development: The need for innovative solutions for promoting win-win interactions. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2009, 10, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Wagner, M. Integrating Sustainability into Firms’ Processes: Performance effects and the moderating role of business models and innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurel, E. Why SMEs invest in environmental measures: Sustainability evidence from small and medium-sized printing firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariail, D.L.; Quinet, G.R.; Thacker, R.M. Creating and fostering sustainable intrapreneurship: A conversation with David Gutiérrez. J. Appl. Manag. Entrep. 2010, 15, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R. ISO 26000 and the standardization of strategic management processes for sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, M. Family and territory values for a sustainable entrepreneurship: The experience of Loccioni Group and Varnelli Distillery in Italy. J. Market. Dev. Compet. 2012, 6, 120–139. [Google Scholar]

- Pastakia, A. Grassroots ecopreneurs: Change agents for a sustainable society. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1998, 11, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Yim, C.K.B.; Tse, D.K. The effects of strategic orientations on technology-and market-based breakthrough innovations. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, F.; Lindsay, N.J.; Shoham, A. Entrepreneurial, market, and learning orientations and international entrepreneurial business venture performance in South African firms. Int. Market. Rev. 2006, 23, 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstein, A. The relationship between market orientation and alternative strategic orientations: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: Two models of strategic momentum. Strateg. Manag. J. 1982, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Strategy-Making and Environment: The third link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1983, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, H.H.; Gumpert, D. The heart of entrepreneurship. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1985, 85, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.H.; Paul, G.W. The relationship between entrepreneurship and marketing in established firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 1987, 2, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, S. The distinctive domain of entrepreneurship research. In Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth; Katz, J., Brockhaus, R., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 119–138. ISBN 978-0762300037. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Busenitz, L.W. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certo, S.T.; Moss, T.W.; Short, J.C. Entrepreneurial orientation: An applied perspective. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettel, M.; Rottenberger, J.D. Examining the link between entrepreneurial orientation and learning processes in small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Golini, R.; Cagliano, R. The role of New Forms of Work Organization in developing sustainability strategies in operations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frishammar, J.; Andersson, S. The overestimated role of strategic orientations for international performance in smaller firms. J. Int. Entrep. 2009, 7, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.G. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, V.; Bowman, C.; Collier, N. Dynamic capabilities: An exploration of how firms renew their resource base. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, B.S. Adaptation: A promising metaphor for strategic management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, R. Strategic flexibility in product competition. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. The development and validation of the organisational innovativeness construct using confirmatory factor analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2004, 7, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. The capabilities of market-driven organizations. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribá-Esteve, A.; Sánchez-Peinado, L.; Sánchez-Peinado, E. The influence of top management teams in the strategic orientation and performance of small and medium-sized enterprises. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. Strategy as a field of study: Why search for a new paradigm? Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Basso, O.; Bouchard, V. Three levels of culture and firms’ entrepreneurial orientation: A research agenda. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.A.; Marino, L. The epistemology of entrepreneurial orientation: Conceptual formation, modeling and operationalization. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 989–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satori, G. Concept misformation in comparative politics. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1970, 64, 1033–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadogan, J.W. International marketing, strategic orientations and business success: Reflections on the path ahead. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwarsd, J.R. Multidimensional constructs in organizational behavior research: An integrative analytical framework. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 144–192. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Li, P.-C.; Evans, K.R. Effects of interaction and entrepreneurial orientation on organizational performance: Insights into market driven and market driving. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Pinkham, B.C.; Yang, H. Entrepreneurial orientation: Assessing the construct’s validity and addressing some of its implications for research in the areas of family business and organizational learning. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M.; Carstedt, G. Innovating our way to the next industrial revolution. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2001, 42, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, S.; El-Kafafi, S. Drivers of sustainable innovation push, pull or policy. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 6, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Brigham, K.H.; Moss, T.W. Long-term orientation: Implications for the entrepreneurial orientation and performance of family businesses. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Luna, J.L.; Garcés-Ayerbe, C.; Rivera-Torres, P. Estrategia medioambiental y expectativas de ventajas competitivas. Cuadernos Estudios Empresariales 2008, 18, 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Özsomer, A.; Calantone, R.J.; Di Benedetto, A. What makes firms more innovative? A look at organizational and environmental factors. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 1997, 12, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforet, S. Effects of size, market and strategic orientation on innovation in non-hightech manufacturing SMEs. Eur. J. Mark. 2009, 43, 188–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, H. Strategic orientations in management literature: Three approaches to understanding the interaction between market, technology, entrepreneurial and learning orientations. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.; Jaju, A.; Puzakova, M.; Rocereto, J.F. The connubial relationship between market orientation and entrepreneurial orientation. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2013, 21, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).