Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection with Harmonic Analysis and Low-Rank Decomposition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

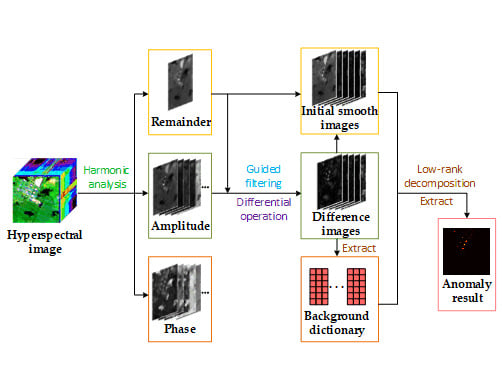

2. Harmonic Analysis and Low-Rank Decomposition

2.1. Hyperspectral Harmonic Analysis

| Algorithm 1. Harmonic analysis |

| 1. Input: Hyperspectral matrix Y = [Y1, Y2, …, YM] ∈ RB×M, maximum harmonic number hmax. |

| 2. Transformation process |

| for each pixel Yi do |

| (1) calculate remainder Re by Equation (2); |

| for h = 1 to hmax do |

| (2) Calculate coefficients of HA by Equations (3)–(6); |

| end for |

| (3) Get the reconstructed pixel Y′i by Equayion (1); |

| end for |

| 3. Output: remainder Re, amplitude Hh and phase Ph. |

2.2. Guided Filtering and Dictionary Construction

2.2.1. Guided Filtering

2.2.2. Dictionary Construction

2.3. Low-Rank Decomposition

| Algorithm 2. Low-rank Decomposition |

| Input: Initial smooth image S, background dictionary D. |

| Initialization: Give λ according to different input data, τ = 10−6, η = 10−6, τmax = 1010, ζ = 1.1, F = U = A = L1 = L2 = 0. |

| while not satisfy the convergence condition (21) do |

| (1) Update variable U according to Equation (17); |

| (2) Update variable F according to Equation (18); |

| (3) Update variable A according to Equation (19); |

| (4) Update Lagrange multipliers L1 and L2 according to Equation (20); |

| (5) Update variable τ, where τ = min(τmax, τ*ζ); |

| end while |

| Return: Coefficient matrix F, sparse matrix A. |

| Calculate anomaly result T according to Equation (22); |

| Output: Anomaly result T. |

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Data Sets

3.2. Detection Performance Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADLR | Abundance and dictionary-based low-rank decomposition |

| AED | Anomaly detector based on attribute and edge-preserving filters |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| AVIRIS | Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer |

| CRD | Collaborative representation-based anomaly detection |

| ENVI | Environment for Visualizing Images |

| GF | Guided filter |

| GoDec | Go Decomposition |

| HA | Harmonic analysis |

| HALR | Harmonic analysis and low-rank decomposition |

| HA-PSO-SVM | Harmonic analysis-particle swarm optimization-support vector machine |

| KRX | Kernel RX |

| LADMAP | Linearized alternating direction method with adaptive penalty |

| LRASR | Low-rank and sparse representation |

| LRR | Low rank representation |

| LRX | Local RX |

| LSMAD | Low-rank and sparse matrix decomposition-based mahalanobis distance method for hyperspectral anomaly detection |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| ROSIS | Reflective Optics System Imaging Spectrometer-03 |

| RPCA | Robust principal component analysis |

| RSAD | Random-selection-based anomaly detector |

| RX | Reed-Xiaoli |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| SSRX | Subspace-based RX |

| STGF | Structure tensor and guided filtering |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| WSCF | Whitening spatial correlation filtering |

References

- Bioucas-Dias, J.M.; Plaza, A.; Camps-Valls, G.; Scheunders, P.; Nasrabadi, N.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral remote sensing data analysis and future challenges. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2013, 1, 6–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, D.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Q. Hyperspectral anomaly detection via discriminative feature learning with multiple-dictionary sparse representation. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, L.; Wen, G.; Qiu, S. Low-rank and sparse matrix decomposition with cluster weighting for hyperspectral anomaly detection. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matteoli, S.; Diani, M.; Corsini, G. A tutorial overview of anomaly detection in hyperspectral images. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2010, 25, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Chang, S.S. Anomaly detection and classification for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 40, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manolakis, D.; Shaw, G. Detection algorithms for hyperspectral imaging applications. IEEE Signal Proc. Mag. 2002, 19, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolakis, D.; Truslow, E.; Pieper, M.; Cooley, T.; Brueggeman, M. Detection algorithms in hyperspectral imaging systems: An overview of practical algorithms. IEEE Signal Proc. Mag. 2014, 31, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, I.S.; Yu, X. Adaptive multiple-band cfar detection of an optical pattern with unknown spectral distribution. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1990, 38, 1760–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.M.; Chang, C.I. Multiple-Window Anomaly Detection for Hyperspectral Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Boston, MA, USA, 7–11 July 2008; pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, G.; Dai, W. A tensor decomposition-based anomaly detection algorithm for hyperspectral image. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 5801–5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteoli, S.; Diani, M.; Corsini, G. Hyperspectral anomaly detection with kurtosis-driven local covariance matrix corruption mitigation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2011, 8, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y. Exploiting structured sparsity for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 4050–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaum, A. Hyperspectral anomaly detection beyond rx. Proc. SPIE 2007, 6565, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Du, B.; Zhang, L. Random-selection-based anomaly detector for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Kernel rx-algorithm: A nonlinear anomaly detector for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2005, 43, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubauskas, M.E.; Legates, D.R.; Kastens, J.H. Harmonic analysis of time-series avhrr ndvi data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2001, 67, 461–470. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubauskas, M.E.; Legates, D.R.; Kastens, J.H. Crop identification using harmonic analysis of time-series avhrr ndvi data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2002, 37, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, B.A.; Jacob, R.W.; Hermance, J.F.; Mustard, J.F. A curve fitting procedure to derive inter-annual phenologies from time series of noisy satellite ndvi data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 106, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, A.; Plaza, A.; Gamba, P. Harmonic mixture modeling for efficient nonlinear hyperspectral unmixing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 4247–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Du, P.; Su, H. Harmonic analysis for hyperspectral image classification integrated with pso optimized svm. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 2131–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaucel, J.M.; Guillaume, M.; Bourennane, S. Whitening spatial correlation filtering for hyperspectral anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–23 March 2005; pp. 333–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Li, J.; Benediktsson, J.A. Hyperspectral anomaly detection with attribute and edge-preserving filters. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 5600–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, K.; Hao, Q.; Duan, P.; Kang, X. Hyperspectral anomaly detection with multiscale attribute and edge-preserving filters. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.; Lei, J. Structure tensor and guided filtering-based algorithm for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 4218–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Nasrabadi, N.M.; Tran, T.D. Sparse representation for target detection in hyperspectral imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2011, 5, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, Q. Collaborative representation for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chanussot, J.; Wei, Z. Joint reconstruction and anomaly detection from compressive hyperspectral images using mahalanobis distance-regularized tensor rpca. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 2919–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Yao, D.; Li, Q.; Zhuang, L.; Zhang, B.; Bioucas-Dias, J.M. A new low-rank representation based hyperspectral image denoising method for mineral mapping. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S. A low-rank and sparse matrix decomposition-based mahalanobis distance method for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 54, 1376–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Plaza, A.; Wei, Z. Anomaly detection in hyperspectral images based on low-rank and sparse representation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 1990–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Wang, B. Hyperspectral anomaly detection based on low-rank representation and learned dictionary. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, W.; Guo, R.; Ayhan, B.; Kwan, C.; Vance, S.; Qi, H. Hyperspectral anomaly detection through spectral unmixing and dictionary-based low-rank decomposition. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 4391–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. A selective kpca algorithm based on high-order statistics for anomaly detection in hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2008, 5, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L.; Vetterli, M.; Devore, R.A.; Daubechies, I. Data compression and harmonic analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1998, 44, 2435–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, Y.; Jiao, W.; Long, T.; He, G.; Gong, C. An extension of phase correlation-based image registration to estimate similarity transform using multiple polar Fourier transform. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomson, D.J. Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. Proc. IEEE 2005, 70, 1055–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, W.; Zhou, H.; Rong, S.; Qian, K.; Yu, Y. Fusion of multi-focus images via a gaussian curvature filter and synthetic focusing degree criterion. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, 10092–10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Kang, X.; Hu, J. Image fusion with guided filtering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2013, 22, 2864–2875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, X. Guided image filtering. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. 2013, 35, 1397–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Lai, R.; Xiong, A. Wavelet Deep Neural Network for Stripe Noise Removal. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 44544–44554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Lai, R.; Xiong, A. Learning Spatiotemporal Features for Single Image Stripe Noise Removal. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 144489–144499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, J.; Qian, K.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, Z. Hyperspectral anomaly detection based on anomalous component extraction framework. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 96, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, L. Hyperspectral anomaly detection by the use of background joint sparse representation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 2523–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Zickler, T. Statistics of real-world hyperspectral images. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2011), Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 20–25 June 2011; pp. 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, S.; Liu, D. Hyperspectral anomaly detection via dictionary construction-based low-rank representation and adaptive weighting. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, K.; Hou, Z.; Ma, D.; Chen, Y.; Du, Q. Anomaly detection in hyperspectral imagery based on low-rank representation incorporating a spatial constraint. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, W.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Lai, Y.M.; Li, W. Low-rank and sparse matrix decomposition-based anomaly detection for hyperspectral imagery. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2014, 8, 083641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Xu, X.; Tao, D. Discriminative godec+ for classification. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2017, 65, 3414–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, R.; Cao, J.; Zhang, J.; Lai, Y.K.; Liu, X. Online low-rank representation learning for joint multi-subspace recovery and clustering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ren, X.; Lin, Z. Linearized alternating direction method with adaptive penalty and warm starts for fast solving transform invariant low-rank textures. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2013, 104, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fazel, M.; Hindi, H.; Boyd, S.P. A rank minimization heuristic with application to minimum order system approximation. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Proceedings of American Control Conference, Arlington, VA, USA, 25–27 June 2001; pp. 4734–4739. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Jiao, L. Low-rank representation with local constraint for graph construction. Neurocomputing 2013, 122, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.F.; Candès, E.J.; Shen, Z. A singular value thresholding algorithm for matrix completion. SIAM J. Optim. 2010, 20, 1956–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, A.; Zhou, R.; Zhu, C. Robust subspace segmentation by self-representation constrained low-rank representation. Neural Process. Lett. 2018, 48, 1671–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Yang, S.; Kalpakis, K.; Chang, C.I. Low-rank decomposition-based anomaly detection. Proc. SPIE 2013, 8743, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Qi, B.; Wang, J. Global and local real-time anomaly detectors for hyperspectral remote sensing imagery. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 3966–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stefanou, M.S.; Kerekes, J.P. A method for assessing spectral image utility. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Set | Salinas | San Diego | Beach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor | AVIRISa | AVIRISa | ROSISb |

| Captured place | Salinas Valley, CA, USA | San Diego, CA, USA | Pavia, Italy |

| Spatial resolution | 3.7 m | 3.5 m | 1.3 m |

| Total band | 224 | 224 | 102 |

| Available band | 204 | 189 | 102 |

| Test image size | 150 × 150 | 100 × 100 | 100 × 100 |

| Datasets | Methods | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RX | LRX | WSCF | CRD | RPCA-RX | LSMAD | AED | HALR | |

| Synthetic | 0.1370 | 0.9823 | 0.9072 | 0.9998 | 0.9602 | 0.9836 | 0.9997 | 0.9998 |

| San Diego | 0.9832 | 0.8467 | 0.9855 | 0.9875 | 0.9799 | 0.9867 | 0.9871 | 0.9939 |

| Beach | 0.9855 | 0.9347 | 0.9819 | 0.9716 | 0.9758 | 0.9828 | 0.7594 | 0.9920 |

| Datasets | Synthetic | San Diego | Beach | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 1 | 0.9999 | 0.9934 | 0.9899 |

| 2 | 0.9996 | 0.9969 | 0.9949 | |

| 3 | 0.9998 | 0.9886 | 0.9899 | |

| 4 | 0.9999 | 0.9832 | 0.9939 | |

| 5 | 0.9998 | 0.9956 | 0.9928 | |

| 6 | 0.9997 | 0.9944 | 0.9915 | |

| 7 | 0.9998 | 0.9939 | 0.9932 | |

| 8 | 0.9999 | 0.9936 | 0.9898 | |

| 9 | 0.9997 | 0.9898 | 0.9942 | |

| 10 | 0.9999 | 0.9968 | 0.9931 | |

| Average AUC | 0.9998 | 0.9926 | 0.9922 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.00011 | 0.0043 | 0.002 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiang, P.; Song, J.; Li, H.; Gu, L.; Zhou, H. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection with Harmonic Analysis and Low-Rank Decomposition. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 3028. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11243028

Xiang P, Song J, Li H, Gu L, Zhou H. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection with Harmonic Analysis and Low-Rank Decomposition. Remote Sensing. 2019; 11(24):3028. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11243028

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiang, Pei, Jiangluqi Song, Huan Li, Lin Gu, and Huixin Zhou. 2019. "Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection with Harmonic Analysis and Low-Rank Decomposition" Remote Sensing 11, no. 24: 3028. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11243028

APA StyleXiang, P., Song, J., Li, H., Gu, L., & Zhou, H. (2019). Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection with Harmonic Analysis and Low-Rank Decomposition. Remote Sensing, 11(24), 3028. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11243028