Abstract

Frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) and orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) technologies play significant roles in millimeter-wave radar and communication. Their combinations, however, are understudied in the literature. This paper introduces a novel OFDM-FMCW dual-functional radar-communications (DFRC) system that takes advantage of the merits of both technologies. Specifically, we introduce a baseband modulation to the traditional FMCW radar system architecture. This integration combines the advantages of both waveforms, enhancing the diversity of radar transmission waveforms without compromising high-resolution distance detection and enjoying the communication capabilities of OFDM in the meantime. We establish the system and signal models for the proposed DFRC and develop holistic methods for both sensing and communications to accommodate the integration. For radar, we develop an efficient radar sensing scheme, with the impacts of adding OFDM also being analyzed. A communication scheme is also proposed, utilizing the undersampling theory to recover the OFDM baseband signals modulated by FMCW. The theoretical model of the communication receive signal is analyzed, and a coarse estimation combined with a fine estimation method for Carrier Frequency Offset (CFO) estimation is proposed. System simulations validate the feasibility of radar detection and communication demodulation.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of radio technology, Dual-Function Radar-Communication (DFRC) systems play an increasingly important role in emerging fields, such as low-altitude economy [1], Internet of Vehicles (IoV) [2], and intelligent transportation [3,4]. These fields demand higher standards for sensing and communication technologies in terms of precision, reliability, and integration [5]. Consequently, the pursuit of integrated sensing and communication technologies has become a hot topic of research in both academia and industry in recent years [6,7], with frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) and orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) being the two most widely studied technologies.

FMCW radar, due to its high precision and resolution, has extensive applications in various fields such as Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADASs), intelligent monitoring, and health monitoring [8,9], and it remains crucial in future emerging applications. Therefore, research on DFRC technology based on FMCW millimeter-wave radar holds significant practical value. In existing studies, although various DFRC technologies have been proposed, such as sidelobe amplitude modulation [10], phase modulation [11], and multi- waveform amplitude keying [12,13], most of these methods are not based on the FMCW radar platform or are highly complex and impractical to implement. Among the methods more suitable for the FMCW platform, the paper [14] proposed a dual-function radar communication system (FRaC) based on FMCW radar waveforms, embedding information through index modulation (IM), including spatial allocation and frequency diversity [15]. Compared to traditional phase-modulated DFRC, this system achieves a higher communication rate but requires complex signal processing algorithms to synchronize and optimize radar and communication functions. The article [16] proposed an MCSIF-DFRC mechanism, effectively implementing DFRC functions through multi-channel separation and spatial information fusion. However, it can be prone to synchronization and parameter estimation errors. The work [17], based on frequency-modulated continuous waves, proposed a DFRC waveform that embeds data using constrained frequency hopping (C-FH) sequence mapping and up/down slopes, achieving efficient data communication and a low-loss radar detection performance. The aim is to balance the communication rate, symbol error rate, and out-of-band leakage, but it faces challenges in design complexity, performance balance, and hardware requirements.

Compared to existing methods, this paper proposes a new approach that combines OFDM with FMCW to achieve DFRC. This OFDM-FMCW DFRC technology not only ensures the high-range resolution characteristic of FMCW radar but also fully utilizes the richness of OFDM signals to enhance the system’s anti-jamming and communication capabilities [18]. Benefiting from OFDM as a key technology in the field of communication, it plays a significant role in modern wireless communication due to its high-speed data transmission, resistance to multipath interference, high spectral efficiency, and strong resistance to fading [19]. FMCW radar, on the other hand, has the advantages of a large bandwidth, high resolution, and low to medium frequency sampling. Therefore, exploring the integration of FMCW radar with OFDM communication technology to achieve DFRC functionality has important research significance and application value [20]. In existing combinations of OFDM and FMCW technologies, the work [21] primarily focuses on maintaining a high resolution and range while reducing the demand for high-speed Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADCs) and Digital-to-Analog Converters (DACs), thus lacking communication functionality. The work [22] proposed Flexible Sensing Insertion OFDM (FSI-OFDM) technology, which maps the time-domain chirp signal to different subcarriers and is equivalent to a short spread spectrum for the subcarriers. However, this method reduces the Doppler measurement range. The work [23] implemented the design of a 155 GHz FMCW and stepped frequency carrier OFDM radar sensor transceiver integrated circuit, which, while consistent with the design approach proposed in this paper, primarily focuses on design aspects related to integrated circuit performance.

This paper systematically studies the integration of FMCW and OFDM in millimeter-wave DFRC. Building upon the traditional FMCW radar system architecture, we introduce a transmission baseband and modulate narrowband OFDM signals with a broadband FMCW local oscillator to form the final integrated sensing and communication transmission waveform. This integration not only enhances the diversity of radar transmission waveforms but also achieves OFDM communication functionality without sacrificing high-resolution distance detection at close ranges. These characteristics perfectly meet the application requirements within the framework of intelligent transportation systems (ITSs). We aim for autonomous vehicles to independently achieve accurate perception of the surrounding traffic conditions during travel and to facilitate information exchange through Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) communication [24]. By integrating sensory data from other vehicles and traffic infrastructure, autonomous vehicles can broaden their perceptual range, providing early warnings of distant traffic conditions or potential obstacles, thus enabling beyond-the-horizon perception. It is important to highlight that the integration of FMCW and OFDM presents novel challenges that have not been addressed in the existing literature. Specifically, two key issues stand out:

- 1

- Radar Echo Model Complexity: The radar echo model in an FMCW-OFDM system is fundamentally different from traditional models. Variations in target distance result in frequency offsets in the echo baseband signal, rendering traditional pulse compression techniques inapplicable.

- 2

- Dual-Carrier Segment Issue in Communication Reception: Asynchrony between the transmission and reception local oscillators, coupled with spatial delays, causes the received baseband signal to exhibit a dual-carrier segment. This leads to abrupt phase and frequency changes, presenting significant hurdles for communication demodulation.

To tackle these critical challenges, this work introduces innovative methods and analytical frameworks, marking a departure from traditional approaches and offering solutions tailored to the unique demands of FMCW-OFDM systems.

The paper makes several significant contributions. Firstly, it derives the radar echo model for the OFDM-FMCW system structure. Secondly, it proposes two pulse compression methods, one in the time domain and another in the frequency domain. The analysis focuses on the phase sensitivity introduced by frequency-domain pulse compression to echo delay, and derives detection range constraint conditions based on pulse compression loss. The paper also compares the performance differences between OFDM-FMCW and traditional FMCW radars. For communication reception, the paper addresses the dual-carrier segment issue by applying undersampling principles and reasonable parameter settings. It introduces a combined method of coarse and fine estimation to achieve a precise Carrier Frequency Offset (CFO) estimation. Finally, system simulations confirm the feasibility of radar detection and communication demodulation, validating the effectiveness of the proposed methods.

The main arrangement of the subsequent paper is as follows. Section 2 mainly introduces the radar system structure and model of the proposed OFDM-FMCW DFRC. Based on the transmission and reception waveform model analysis in Section 2.1, time-domain- and frequency-domain-matched filtering methods are proposed in Section 2.2 and Section 2.3, respectively, with a brief summary of the two pulse compression methods in Section 2.4. In Section 3, the communication received signal model is established, and a detailed analysis is provided of the impact of the sudden frequency changes in the echo carrier due to different transmission and reception sources on the final demodulation. In Section 3.2, an estimation method based on coarse and fine estimation is proposed. In Section 4, systematic radar and communication simulations are conducted to validate the correctness of the proposed theories.

2. OFDM-FMCW Radar System Model

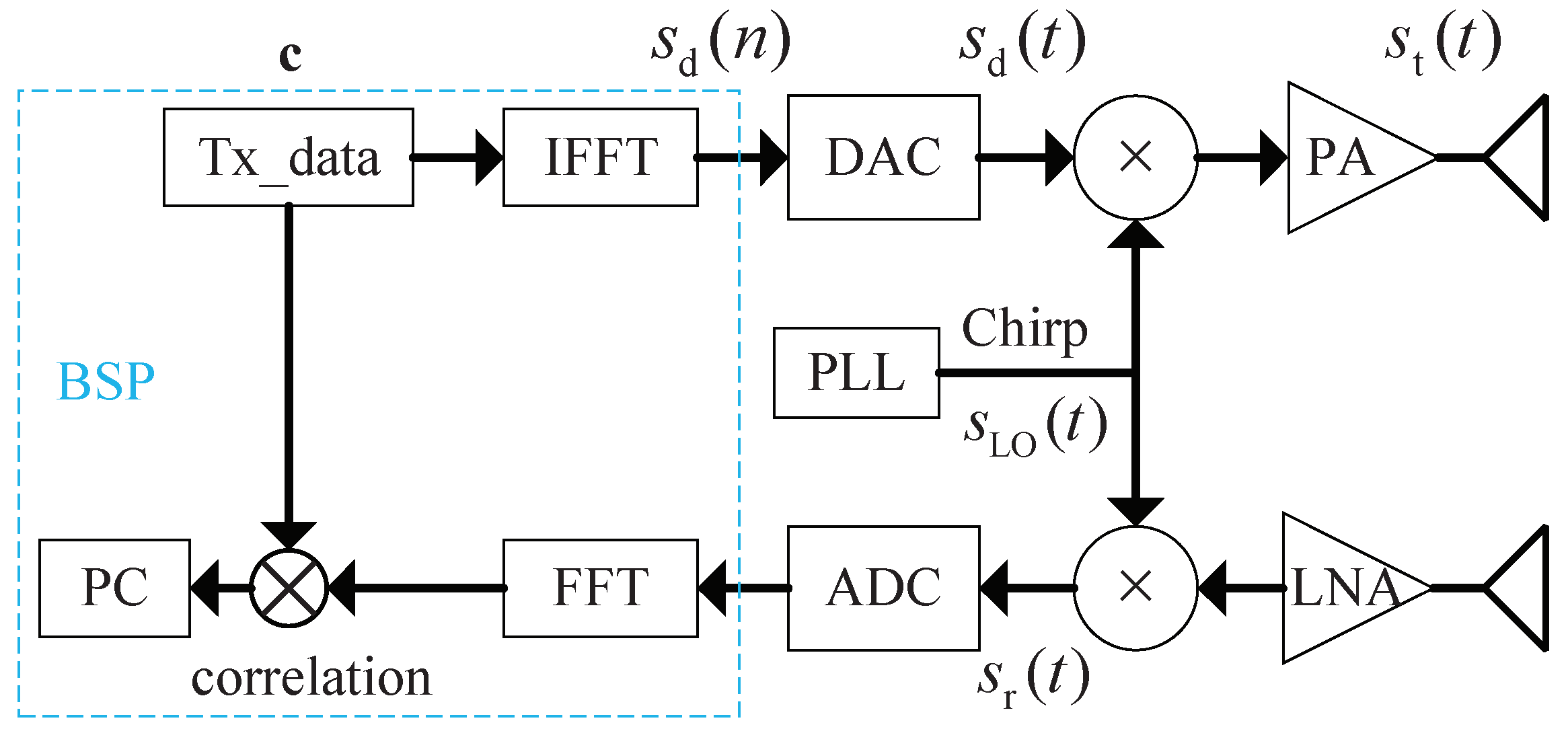

The transmission signal of a traditional FMCW radar is primarily determined by the local oscillator. By adding a baseband signal to the transmitter, the proposed DFRC system structure is shown in Figure 1. In this case, the local oscillator signal remains a chirp signal, and by setting the baseband transmission signal to an OFDM waveform, an OFDM-FMCW DFRC system is formed, with the final transmission signal being the superposition of traditional FMCW and OFDM signals.

Figure 1.

OFDM-FMCW System Structure.

2.1. Radar Signal Model

For a traditional FMCW radar, the transmission signal, which is the local oscillator signal, can be expressed as

where is the initial frequency, is the frequency modulation slope, and and are the bandwidth and time width of the chirp signal, respectively, while is the rectangular function, which is 1 for and 0 otherwise. Let the delay of the single-point target echo be and the velocity be v; then, the Doppler frequency is , and thus the baseband signal of the target echo after dechirping is

where is the echo strength of the target and is the wavelength of the transmitted carrier frequency.

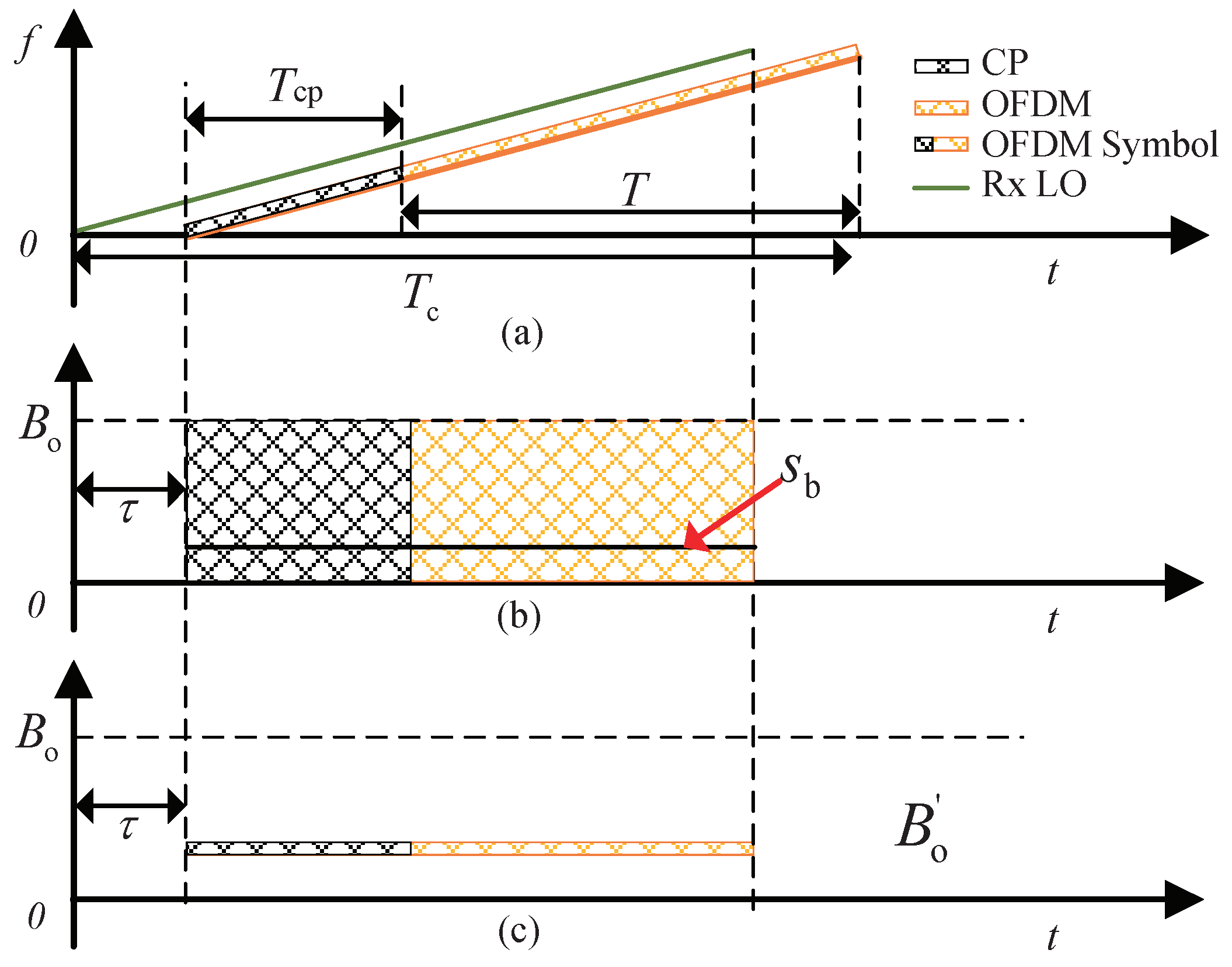

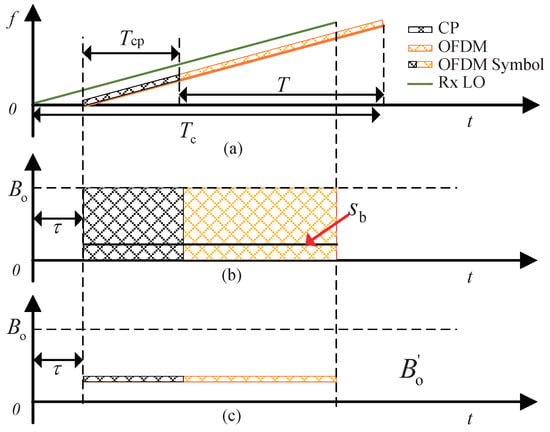

For the proposed DFRC radar subsystem, as shown in Figure 1, compared to the traditional FMCW radar, an additional baseband OFDM modulation term is present. In the generation process of the OFDM transmission signal, the data symbol vector (such as QAM or PSK symbols) mapped onto each subcarrier is transformed into a time-domain signal through IFFT, where m is the subcarrier index and M is the number of subcarriers. This process ensures the orthogonality of the subcarriers in the time domain and also constrains the relationship between the sampling frequency and the subcarriers. To effectively suppress Intersymbol Interference (ISI) and Interchannel Interference (ICI), a cyclic prefix (CP) is generally added to the OFDM signal. As shown in Figure 2a, where T is the effective time length of the OFDM signal and is the cyclic prefix time length, we let the time width of the local oscillator chirp signal be the same as the time width of an OFDM symbol, then . We then let the sampling frequency of the DAC be and the number of discrete points corresponding to one OFDM symbol be N, then . When then let , where is the OFDM signal bandwidth, then the subcarrier frequency interval satisfies

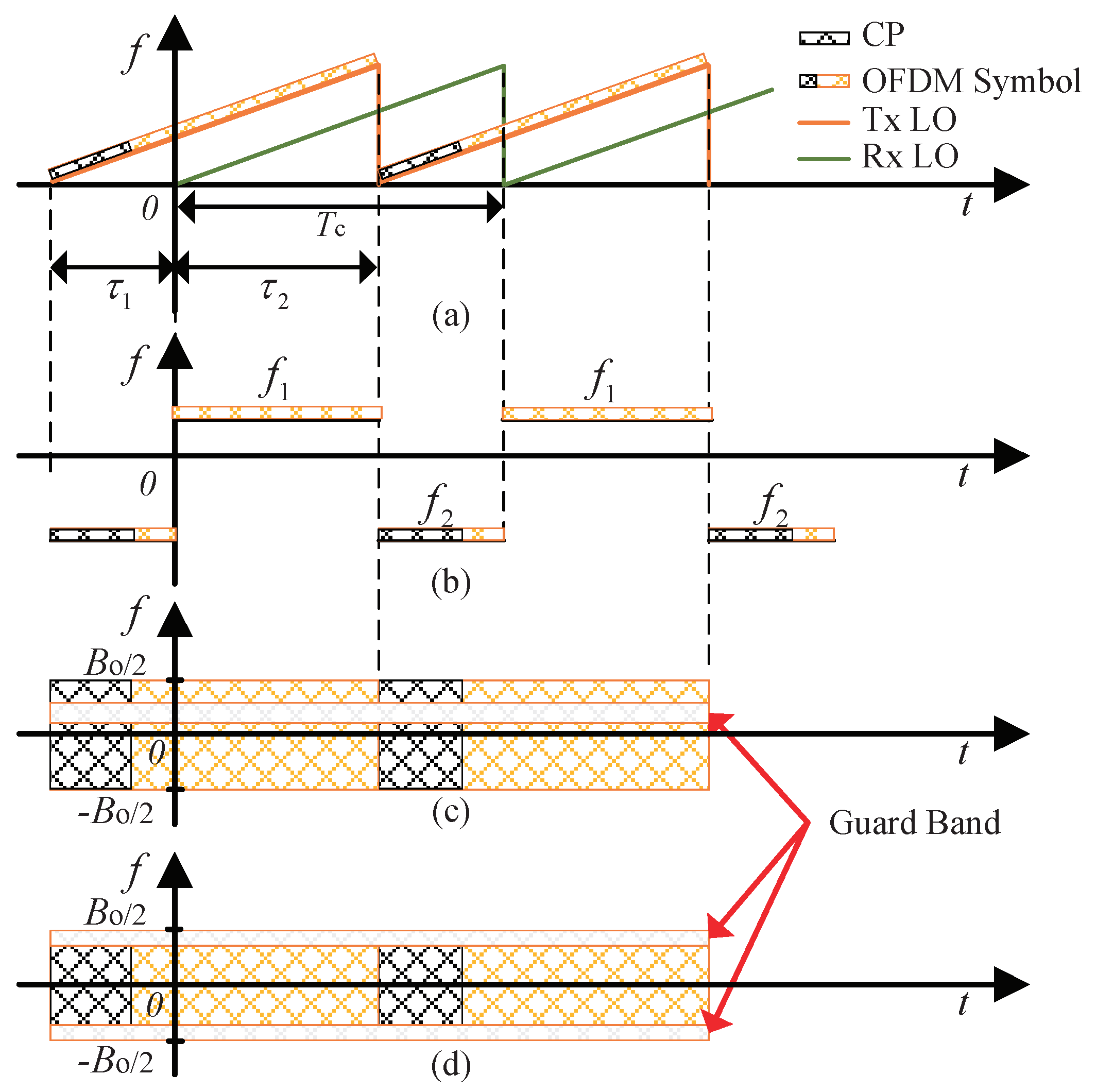

Figure 2.

OFDM-FMCW Radar Echo Processing. (a) Time-frequency of OFDM-FMCW transmit-receive signals; (b) Baseband time-frequency post-FMCW dechirping; (c) Baseband time-frequency at reduced OFDM bandwidth .

Thus, the time-domain waveform of the transmitted OFDM signal can be expressed as

where n is the discrete time sequence, m is the subcarrier index, and is the OFDM data sequence. The corresponding analog continuous-time signal after DAC conversion can be expressed as

After upconversion by the chirp local oscillator, the final transmitted signal waveform is

The baseband waveform of the target reflection echo signal after dechirping with the local oscillator signal (1) is

where “∗” denotes the conjugate. At this point, the baseband echo is the result of the transmitted baseband signal being delayed and multiplied by the traditional FMCW baseband echo.

2.2. Time-Domain Correlation-Matched Filtering

In traditional OFDM-based communication systems for radar detection, since the local oscillator signal is a single carrier frequency, the received echo is the transmitted signal (5) after being reflected by the target with a time delay. Compared to (7), the baseband signal of the echo can be expressed as

The corresponding pulse compression result is the auto-correlation result of the transmitted waveform and the received waveform

Here, represents the echo delay introduced by the target distance, and represents the time delay of the cross-correlation function. Therefore, Equation (9) indicates that the time-domain-matched pulse compression result of traditional OFDM signals is the translation of its transmitted signal’s autocorrelation function along the time axis based on the echo delay of different targets.

Similar to the traditional time-domain correlation pulse compression method, the echoes from different distances based on the OFDM-FMCW signal (7) can be understood as OFDM signals with different carrier frequencies. Thus, we can construct the echo-matching coefficients for targets at different distances to achieve time-domain-signal-matched filtering.

The matching filter coefficients for a target echo delay of can be expressed as

where

Compared to (2), the matching coefficient (11) lacks the Doppler term, thus preserving the target’s velocity information after matched filtering. The process of time-domain matching based on the matching coefficient (10) can be expressed as

When , then ; at this point, the two signals are perfectly matched, and attains its maximum value. However, when , the matching result is approximately zero.

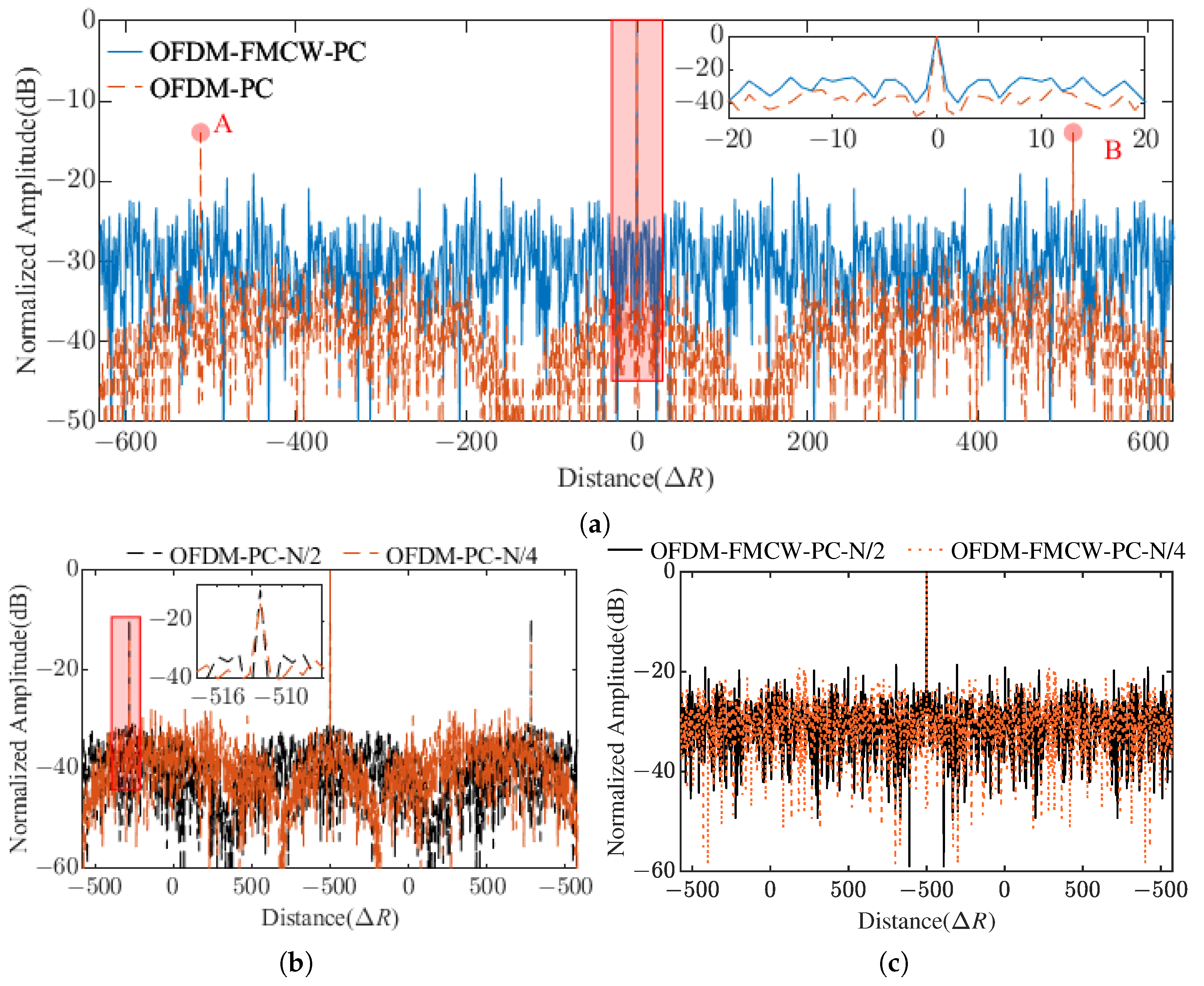

Comparing the time-domain-matched filtering results of OFDM-FMCW with traditional OFDM, as shown in Figure 3, as (9) and (12). The x-axis represents the normalized distance based on range resolution, with the range resolution of the OFDM signal being and that of the OFDM-FMCW signal being . It can be observed that the bottom noise of the OFDM-FMCW pulse compression is relatively high, but it optimizes the interference false targets in the traditional OFDM pulse compression results caused by the CP, namely the A and B peaks in Figure 3a. Self-interference is a critical issue in radar and communication systems. The addition of a cyclic prefix in OFDM signals can mitigate multipath effects and prevent ISI and ICI, thereby enhancing signal integrity and the accuracy of demodulation. The length of the cyclic prefix is determined by the maximum multipath delay spread in the environment. A longer cyclic prefix can improve the receiver’s resistance to multipath interference but reduces the efficiency of bandwidth usage. For traditional OFDM signals used in radar detection, the addition of a cyclic prefix can lead to an increase in self-interference false targets. This is because the introduction of the cyclic prefix increases the redundancy of the signal in the time domain, making it easier for false echo signals to be generated at the radar receiver, which affects the accuracy of target detection. As shown in Figure 3b, the difference in the strength of self-interference false targets for traditional OFDM signal pulse compression with cyclic prefix lengths of and is approximately 4.6 dB, where N is the effective sequence length of the OFDM signal. In contrast, the pulse compression results of the OFDM-FMCW waveform are not affected by the cyclic prefix, as shown in Figure 3c. This is because the echo delay of different targets only causes a time shift in traditional OFDM signals, allowing the cyclic prefixes of different targets to form a certain degree of correlation. However, the echo delay of different targets in OFDM-FMCW signals results in frequency offsets, preventing the cyclic prefixes of different targets from forming direct correlations.

Figure 3.

(a) Comparison of time-domain pulse compression results between OFDM and OFDM-FMCW signals; (b) Comparison of pulse compression results for OFDM signals with different cyclic prefix lengths; (c) Comparison of pulse compression results for OFDM-FMCW signals with different cyclic prefix lengths.

This method, while simple, involves different matching coefficients for targets at various distances, necessitating the construction of matching filter coefficients corresponding to different distances within the detection range to perform traversal matching on the echo signals. Consequently, the computational load increases linearly with the precision and range of traversal. Moreover, to ensure the pulse compression effect, the step size of in the matching coefficient should be less than or equal to the echo delay corresponding to the range resolution, i.e.,

2.3. Frequency-Domain Correlation-Matched Filtering

To reduce the excessive computational load caused by the traversal of constructing matching coefficients in the time-domain pulse compression process, we further investigate the frequency-domain pulse compression method to reduce the pulse compression computational load and achieve rapid pulse compression.

2.3.1. Principle of Frequency-Domain Correlation-Matched Filtering

By conducting a spectral analysis of the echo baseband signal (7), according to the concept that the Fourier transform of a time-domain product equals the frequency-domain convolution, the result can be expressed as

where represents different carrier frequency points and ⊗ denotes the convolution operation. Let , representing the spectral result of the OFDM signal component in the received signal, where is the spectral result of the transmitted baseband signal . From (4), it is known that and is the frequency domain result of . From (2), it is known that the signal is a single-frequency signal determined by the target delay and velocity v. Let its corresponding frequency be ; then, its Fourier transform is an impulse function, which is the pulse compression result of traditional FMCW

Therefore, (14) can be further organized into

Thus, the result of (16) can be understood as the data symbol vector being superimposed with different phase shifts and then being shifted to the position.

Performing cross-correlation between and , according to the derivation in Appendix A, we obtain

where represents the frequency axis delay quantity. Expression (17) indicates that the cross-correlation function between and is essentially the convolution of with the cross-correlation function . Furthermore, from (15) and the shifting property of the impulse function, it is known that the result of physically means that the cross-correlation function is shifted to the position on the frequency axis. Thus, the correlation function between the transmitted phase encoding and the phase encoding in the received signal determines the performance of the pulse compression, while reflects the target’s position and velocity information.

2.3.2. Time-Delay Sensitivity of Frequency-Domain Pulse Compression Phase Encoding

Similar to the Doppler sensitivity issue in the time-domain pulse compression of traditional phase-encoded signals, the sensitivity of pulse compression after combining OFDM with FMCW stems from a phase mismatch caused by time delay. Expanding in (17), we obtain

Since corresponds to the encoded symbols of the transmitted data and can be considered as random phases, the accumulation is non-zero only when , i.e., . Therefore, the above simplifies to

From the result (19), it can be seen that the correlation degrades with an increase in the delay quantity .

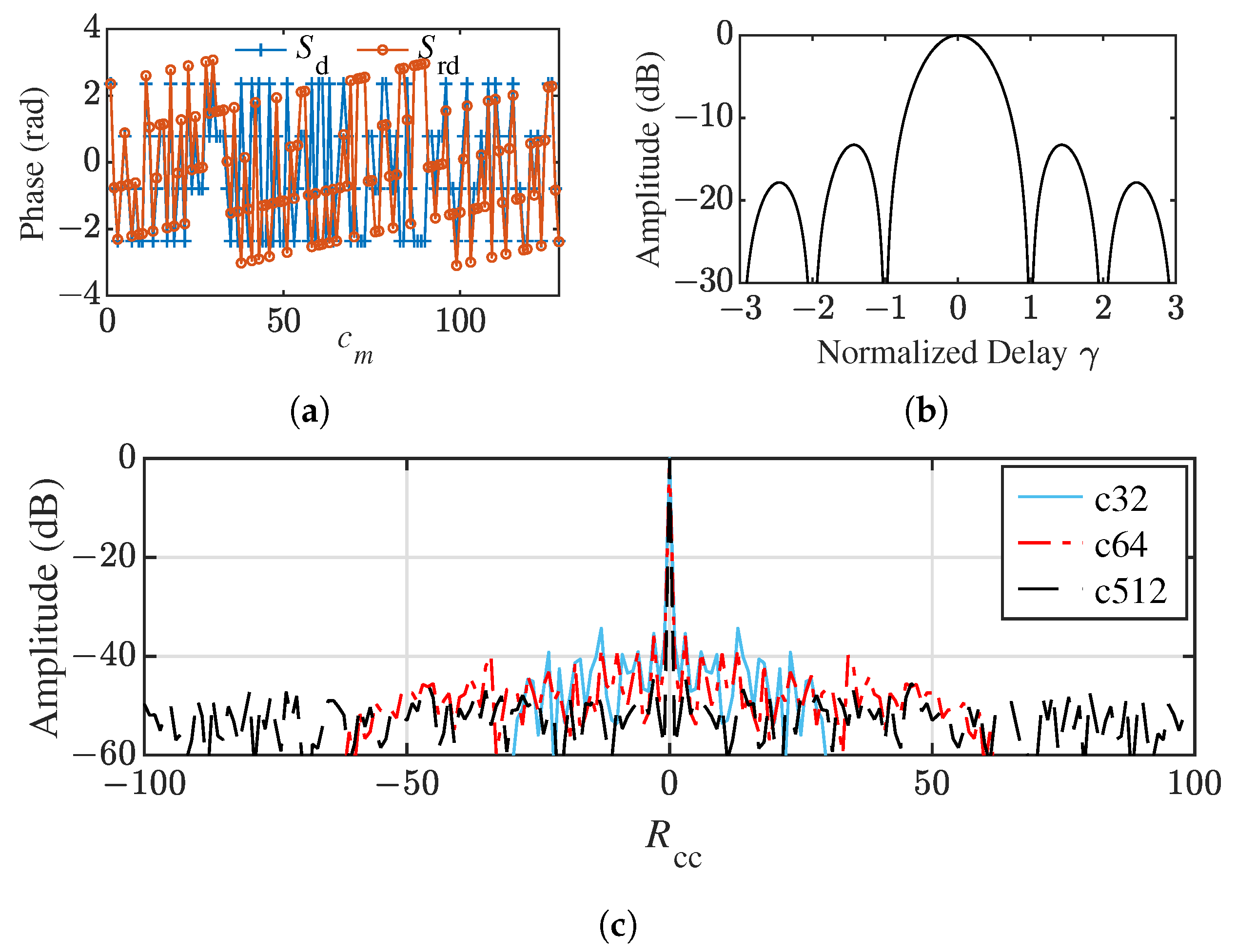

As shown in Figure 4a, when the time delay , a clear mismatch occurs in the QPSK phase encoding, where is the DAC sampling period of the OFDM signal. Figure 4b corresponds to the pulse compression loss caused by the target echo delay in (19), where the normalized delay is . It can be seen from the figure that, when the delay exceeds one sampling point, i.e., , the pulse compression result forms a zero point. When the delay , the resulting pulse compression loss is approximately dB. During the generation of the OFDM signal, the DAC sampling frequency satisfies , so the maximum frequency contained in the OFDM signal is . As shown in Figure 2b, when the echo baseband sampling frequency is still , the signal produced by dechirping causes a frequency shift of in the OFDM spectrum. Due to spectral aliasing, the OFDM spectrum in the echo will cycle shift with the frequency offset caused by . We define the maximum acceptable pulse compression loss as when the phase shift caused by the target delay to the OFDM signal is . At this point,

Figure 4.

(a) Phase encoding variation due to delay; (b) pulse compression loss due to delay; (c) autocorrelation diagram of different OFDM orders.

Drawing from the constraints on echo delay imposed by the acceptable range of pulse compression loss due to a frequency-domain phase mismatch as described in (20), and in conjunction with the established relationship , we define the OFDM-FMCW Max. lossless distance as

To reduce the loss caused by pulse compression mismatch and increase the radar detection range, the actual bandwidth of the OFDM signal used can be reduced based on (21). Let the actual bandwidth of the OFDM signal be

where, represents the utilization rate of the bandwidth . Then , which means that, when the signal bandwidth is reduced by a factor of , the maximum detection range will increase by a factor of . As shown in Figure 2c, this is the case when the effective bandwidth used is small.

For different carrier numbers of OFDM encoding , after 256 accumulations of matching results, the ambiguity function zero Doppler cut plane diagram is shown in Figure 4c. When the OFDM signal has a full bandwidth with 512 subcarriers, the sidelobes will slightly increase when the number of subcarriers corresponding to is 64 and 32, respectively, due to the reduction of bandwidth .

From (17), it is evident that the detection performance of the proposed OFDM-FMC waveform for targets is still constrained by the characteristics of traditional FMCW radars, and the range and velocity detection performance under this waveform is consistent with that of traditional FMCW radars, primarily depending on . The maximum unambiguous range of traditional FMCW is given by

where C is the speed of light and is the frequency modulation slope of the chirp signal. Thus, the maximum detection range of OFMD-FMCW is the intersection of the constraints given by (21) and (23), i.e.,

Taking into account the relatively low signal-to-noise ratio of echoes in practical systems, the effective detection range of the actual system should be less than the maximum detection range constrained by the system, as indicated by (24). The range resolution, velocity resolution, and maximum unambiguous speed are all calculated in the same way as traditional FMCW radar.

where is the carrier wavelength and I is the number of pulse accumulations.

2.4. Comparison of Two Pulse Compression Differences

Comparing Equations (12) and (17), these two pulse compression methods have fundamental differences and their own advantages. Firstly, the radar range resolution, velocity resolution, and speed measurement range obtained by these two methods are consistent with traditional FMCW radar. Secondly, the time-domain pulse compression method described in Section 2.2 has a large computational load but simple logic that is suitable for parallel computing. The frequency-domain pulse compression method described in Section 2.3 has a smaller computational load, but the maximum detection range is greatly affected by the bandwidth . Therefore, to achieve a better detection range, the actual OFDM communication bandwidth used will be reduced.

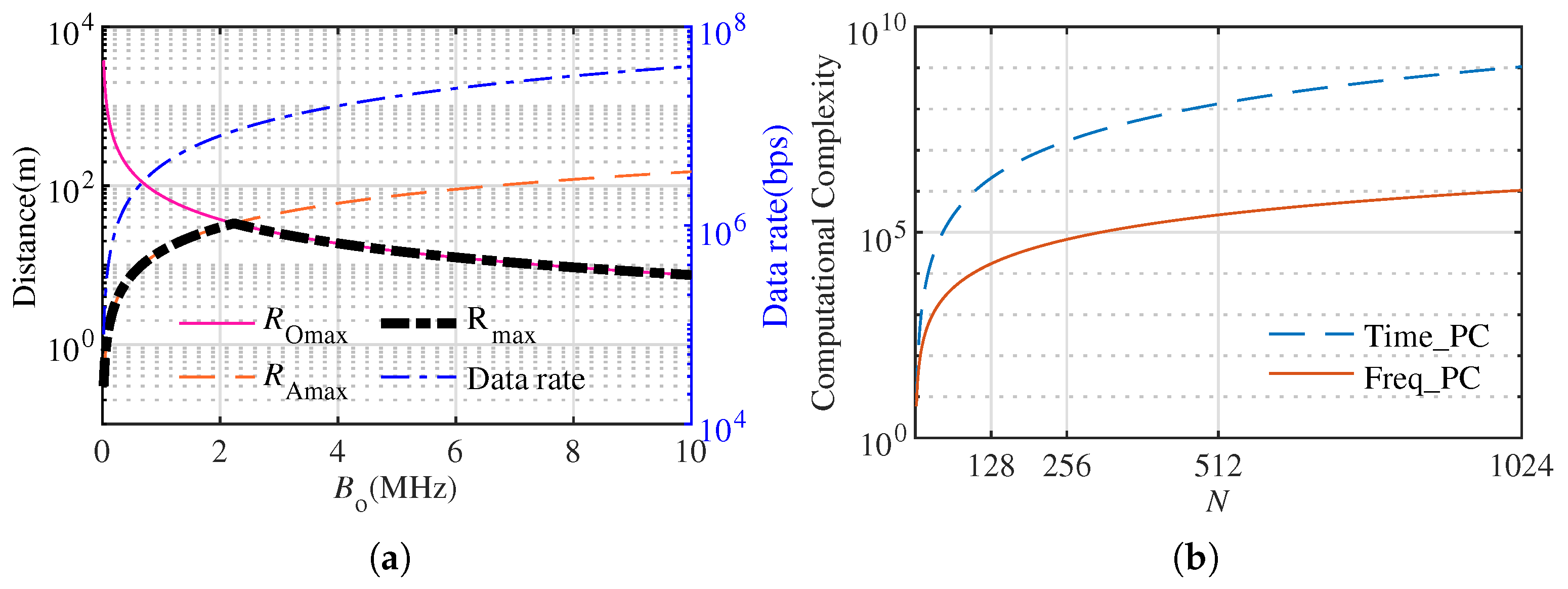

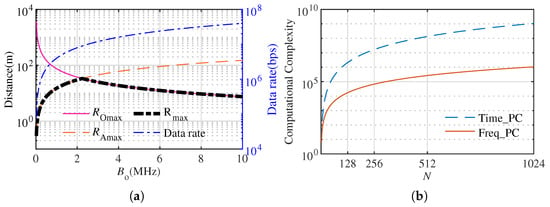

Figure 5a depicts the relationship between the maximum detection range of radar and the communication data rate, both as functions of the transmitted baseband signal bandwidth , when employing the two pulse compression techniques. When the chirp duration is and the sampling rate of the radar reception channel baseband is , utilizing the time-domain pulse compression method, according to (12), the maximum detection range of the radar is , which increases linearly with . In contrast, when employing the frequency-domain pulse compression approach, according to (24), the maximum detection range is the minimum of and . The bolded curve in the figure indicates that this range initially increases and then decreases with the signal bandwidth . Meanwhile, the communication data rate for both methods increases linearly with . Therefore, for different requirements of the detection range and communication bandwidth, appropriate parameters can be selected through trade-offs to meet various scenario needs.

Figure 5.

(a) The variation in the maximum detection range and communication bandwidth with the transmission baseband signal bandwidth . (b) Comparison of computational complexity between time-domain and frequency-domain pulse compression.

There is a substantial computational disparity between the two pulse compression methods. Assuming the number of received echo sample points is N, the autocorrelation computation for an N-point vector is . When utilizing the time-domain method, under the constraint of (13), we consider , where is the step factor for traversing the matching coefficients within the interval . This results in a total computational complexity of . If the proposed frequency-domain method is applied, the computational complexity for converting the echo data to the frequency domain is , plus the autocorrelation computation, yielding a total computational complexity of . To visually illustrate the difference in computational workload between these two methods, Figure 5b depicts the disparity in computational complexity under varying values of N when . It is evident that, at , the computational load of the time-domain method is approximately 500 times that of the frequency-domain method.

3. Communication Signal Model and Demodulation

For the communication end, due to the asynchronization and different sources of the transmit and receive systems, the frequency difference and propagation delay-induced frequency difference between the transmit and receive local oscillators will increase the complexity of the sampling time offset (STO), CFO, and channel error estimation for the OFDM signal.

3.1. Communication Signal Model

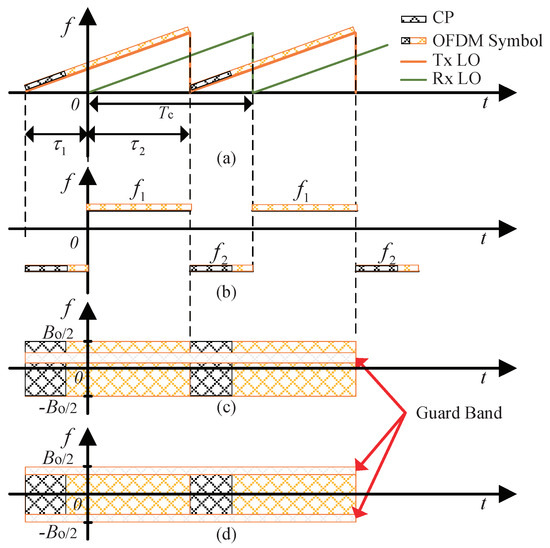

For a single-transmitter single-receiver system, the signal variation process at the communication reception end is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Signal variation process at the communication receiver. (a) Time-frequency diagram of ODFM-FMCW transmit-receive signals; (b) Time-frequency diagram of communication reception baseband; (c) Baseband time-frequency diagram after undersampling in communication reception; (d) Baseband time-frequency diagram after CFO compensation in reception.

As shown in Figure 6a, the transmitted OFDM-FMCW signal is

where i is the chirp index (OFDM symbol index), is the duration of one chirp (OFDM symbol period), K is the frequency modulation slope, and represents the OFDM baseband signal for different symbols, expressed as

The receive end local oscillator signal is

After downconversion by the receive local oscillator (28), the baseband signal with two carrier frequencies, denoted as and , is obtained as shown in Figure 6b. Taking the start of the communication receive end local oscillator signal as time 0, as shown in Figure 6a, the radar transmit end OFDM signal leads the communication receive end local oscillator by , i.e., in the figure. The lag time for the next OFDM symbol is . Based on the conclusions of Equations (2) and (7), the baseband signal shown in (29) can be derived.

Here, is the complex channel parameter and is the system noise.

From (29), it is known that the frequencies of the received baseband during these two time intervals are

Thus, . Considering the bandwidth of the OFDM signal, the total signal bandwidth of the received baseband is

To achieve acquisition of the broadband signal in (31), extremely high performance and sampling frequency requirements for the ADC would be necessary, and this is very impractical in reality. However, although the communication reception in Formula (31) indicates a large required reception bandwidth, the bandwidth carrying communication information remains . Therefore, to reduce the sampling rate requirements at the communication end, undersampling can be considered to achieve an effective signal acquisition. Considering the convenience of OFDM signal demodulation, the relationship between the receive end sampling frequency and the bandwidth of the OFDM signal and chirp signal is set as

where denotes the set of positive integers. Therefore, after undersampling by the ADC,

where denotes the remainder. This means that, after undersampling, . From (7), it is known that this frequency is also the Carrier Frequency Offset of the OFDM signal at the communication receive end. It should be noted that there is a phase discontinuity at the frequency switch between and , i.e., at time . According to (29), the specific phase discontinuity can be calculated as

This phase change can be equivalent to adding a fixed amplitude and phase error during the communication transmission process, so this error can be compensated for during the estimation of each OFDM channel.

Theorem 1.

A single-frequency signal that experiences a fixed phase jump at a specific time point can have its spectral peak equivalent to adding a fixed amplitude and phase error in the communication transmission process.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Let the discrete single-frequency signal sequence have a length of N with an initial phase of and a frequency of k. Then, its Fourier transform at the k frequency point is

If a phase jump of occurs at position L in this sequence, then

where is a determined complex number. Comparing (35) and (36), it can be understood that (36) multiplies the original ideal peak values at each frequency point by the fixed complex term , so this process can be equivalent to adding a fixed amplitude and phase offset at different frequency points based on the original channel. □

The spectral result of the baseband received signal after undersampling is shown in Figure 6c. When the effective signal bandwidth of the OFDM is large, i.e., the spectral protection band is small, the large causes spectral aliasing. Considering transmission attenuation and channel effects, the baseband communication received signal can be expressed as

where represents the equivalent channel error, A is the received signal amplitude, is the channel complex parameter for different subcarriers, and is the amplitude-phase error quantity introduced by the phase jump in (34).

3.2. OFDM Demodulation

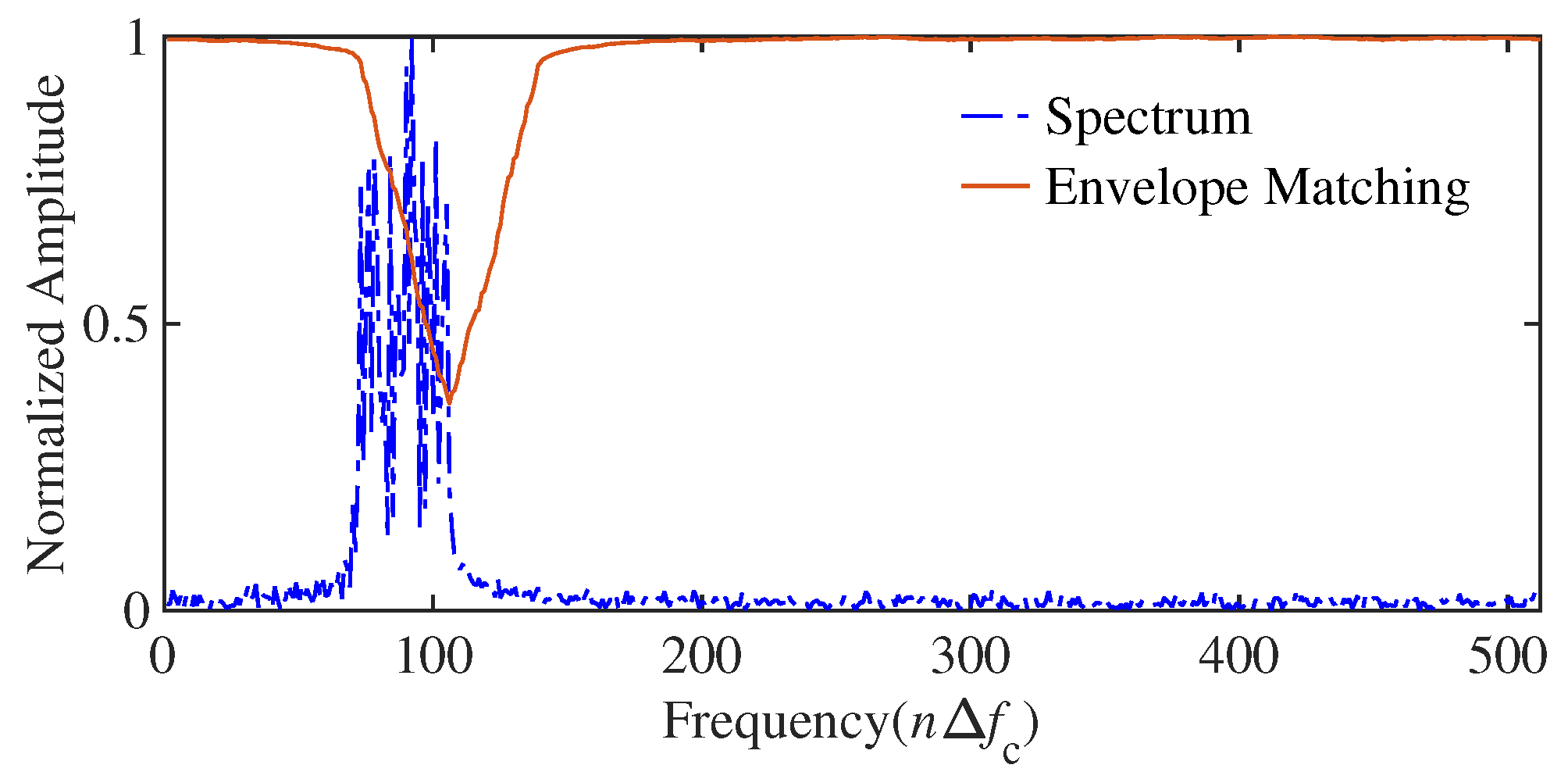

According to the OFDM signal at the communication receive end shown in (37), it does not differ much from traditional OFDM communication. Both face the challenges of STO estimation, CFO estimation, and channel estimation. STO and channel estimation can be fully implemented based on traditional methods (for details refer to [25]), while CFO estimation in the OFDM-FMCW system is relatively more troublesome. Since , the frequency offset error range is large. The method based on [25] can only achieve an error estimation within the range of , and thus it cannot directly meet this application scenario. Therefore, this paper proposes using the OFDM spectral protection band for rough CFO estimation and then using the traditional method in [25] for fine estimation to achieve the precise estimation of the final frequency offset. As shown in Figure 6d, the diagram illustrates the baseband waveform’s time-frequency plot post-CFO compensation.

The ideal OFDM signal spectrum is symmetrically distributed around the zero frequency point with a rectangular shape. A large frequency offset causes spectral aliasing, causing the rectangular function to cycle shift within the sampling frequency band. The existence of the spectral protection band creates a gap in the entire spectral bandwidth. In standard OFDM communication, when is less than the cyclic frequency , the spectral gap is located at the edge of the frequency band. In the OFDM-FMCW scenario, may be randomly distributed throughout the sampling frequency band, causing the spectral gap position to also be randomly distributed. Let the total number of subcarriers of the OFDM signal be M, with effective subcarriers and protection band subcarriers, satisfying . By using a rectangular function of width to cyclically shift match the envelope of the OFDM spectrum, the minimum position of can be determined. However, due to being limited by the spectral resolution, the estimation accuracy of this method is the same as the spectral resolution.

4. Simulation Analysis

To further investigate the accuracy and performance of the theory proposed in Section 2, this section will conduct system simulation experiments to analyze the radar and communication performance in detail. The proposed millimeter-wave OFDM-FMCW DFRC system is particularly well suited for autonomous vehicles in intelligent transportation systems. In the context of highway autonomous driving, the DFRC system is capable of accurately detecting vehicles and obstacles ahead, providing crucial data for functions such as adaptive cruise control (ACC), emergency braking assistance, and lane change assistance, ensuring driving safety. Additionally, it can transmit data in real-time via high-bandwidth communication, supporting V2V and V2I information exchanges. This real-time data sharing allows vehicles to anticipate traffic conditions, optimize driving routes, and implement adaptive cruise control and preventive collision avoidance, thereby significantly enhancing traffic efficiency and safety. Based on this application scenario, we have conducted simulation analyses for both the radar and communication systems.

At the transmitter, each chirp is set to last for , carrying a complete OFDM symbol. The effective duration of the OFDM signal is , with a cyclic prefix of . Consequently, the subcarrier spacing of the OFDM signal, denoted as , is 25 kHz. Assuming a total of 512 subcarriers, the bandwidth of the OFDM signal is 12.8 MHz. Each subcarrier of the OFDM signal employs 4-PSK modulation, carrying 2 bits of information. If the radar pulse compression utilizes the time-domain correlation matching method described in Section 2.2, the OFDM can transmit data at the full bandwidth (assuming no need for spectral protection bands). At this rate, the communication information carrying capacity per second is , which equates to a data rate of 20.48 Mbps (megabits per second). If the frequency-domain correlation-matching pulse compression method outlined in Section 2.3 is used, the effective bandwidth of the OFDM signal must be reduced to ensure that the pulse compression loss, corresponding to the maximum detection range as shown in (23), is within an acceptable range. As shown in Table 1, the effective number of subcarriers for the OFDM signal is 32, corresponding to an effective bandwidth of only 0.8 MHz, or in (22), at which point the communication transmission data rate is . Based on the communication demodulation method described in Section 2.4, the chirp bandwidth and the OFDM signal bandwidth should satisfy (32), hence should be an integer multiple of . Here, we design , meaning is 100 times . These two pulse compression methods can support information transmission at two different communication rates to accommodate the needs of various application scenarios. For instance, in autonomous driving, this enables the exchange of small amounts of data, such as vehicle coordinates, speed, and emergency braking status, between vehicles, as well as the collection of point cloud data and map updates between vehicles and surrounding infrastructures, which involves the exchange of large amounts of data.

Table 1.

Parameters of the OFDM-FMCW Radar.

4.1. Radar System Simulation

Based on the system simulation parameters in Table 1, the main parameter results for the corresponding radar performance are shown in Table 2. At this time, based on (21), the maximum pulse compression lossless distance is approximately 93.69 m, and based on (23), and according to the FMCW frequency modulation slope and sampling rate, the maximum unambiguous detection distance is 74.95 m. Therefore, using (24) to determine the minimum value between the two, the final system detection distance is 74.95 m. The distance resolution calculated by (25) is m, the maximum unambiguous speed is m/s, and the velocity resolution is m/s.

Table 2.

Performance of the OFDM-FMCW Radar.

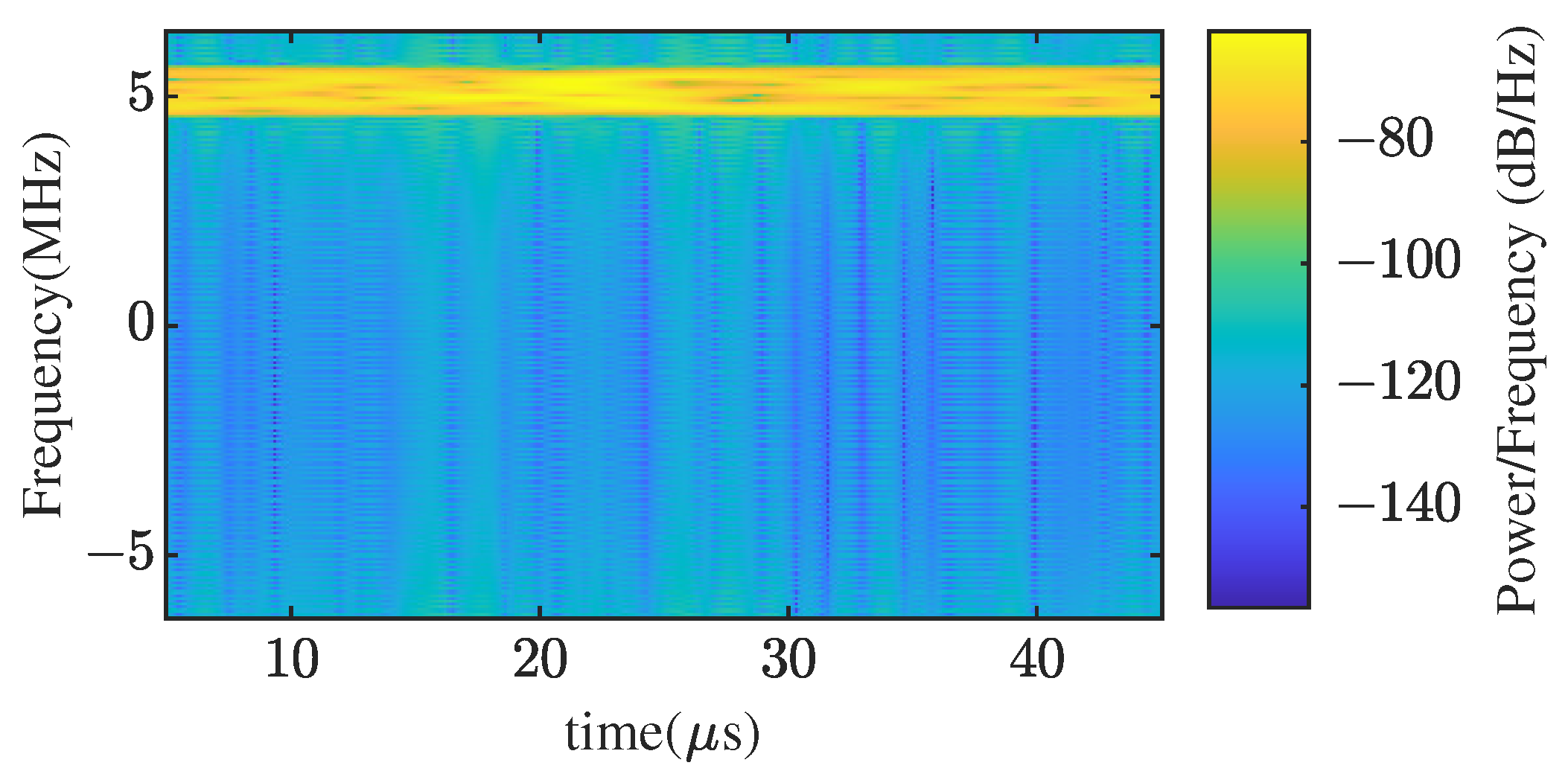

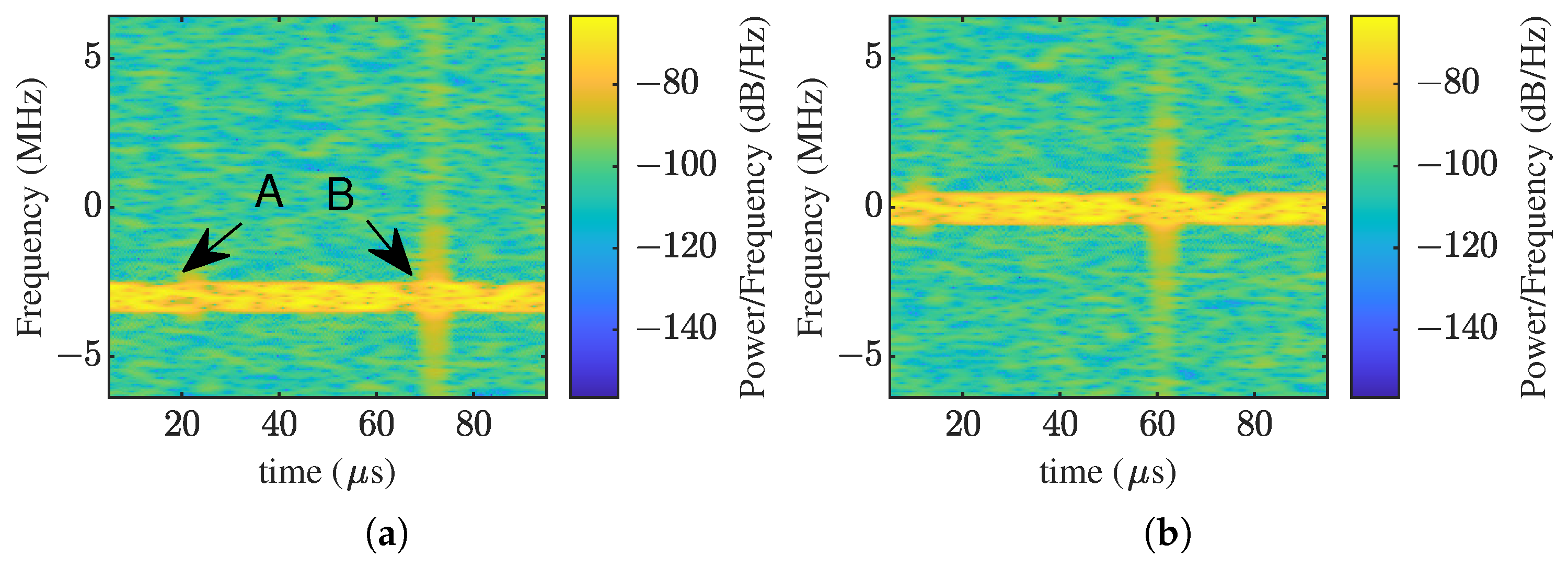

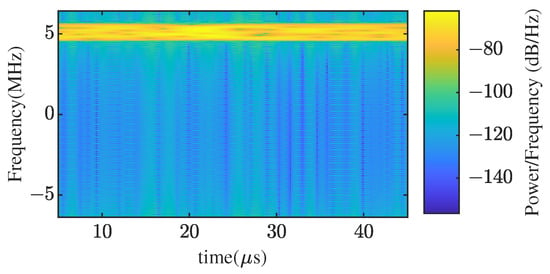

For a single-target scenario, assume it is located at 30 m. The short-time Fourier spectrum of the radar echo baseband signal is shown in Figure 7, corresponding to the situation in Figure 2c in Section 2.1. At this time, the OFDM signal spectrum in the echo is located at ∼ MHz, with the center frequency at 5.12 MHz, corresponding to the traditional FMCW signal echo spectrum.

Figure 7.

Radar Echo Time-Frequency Diagram.

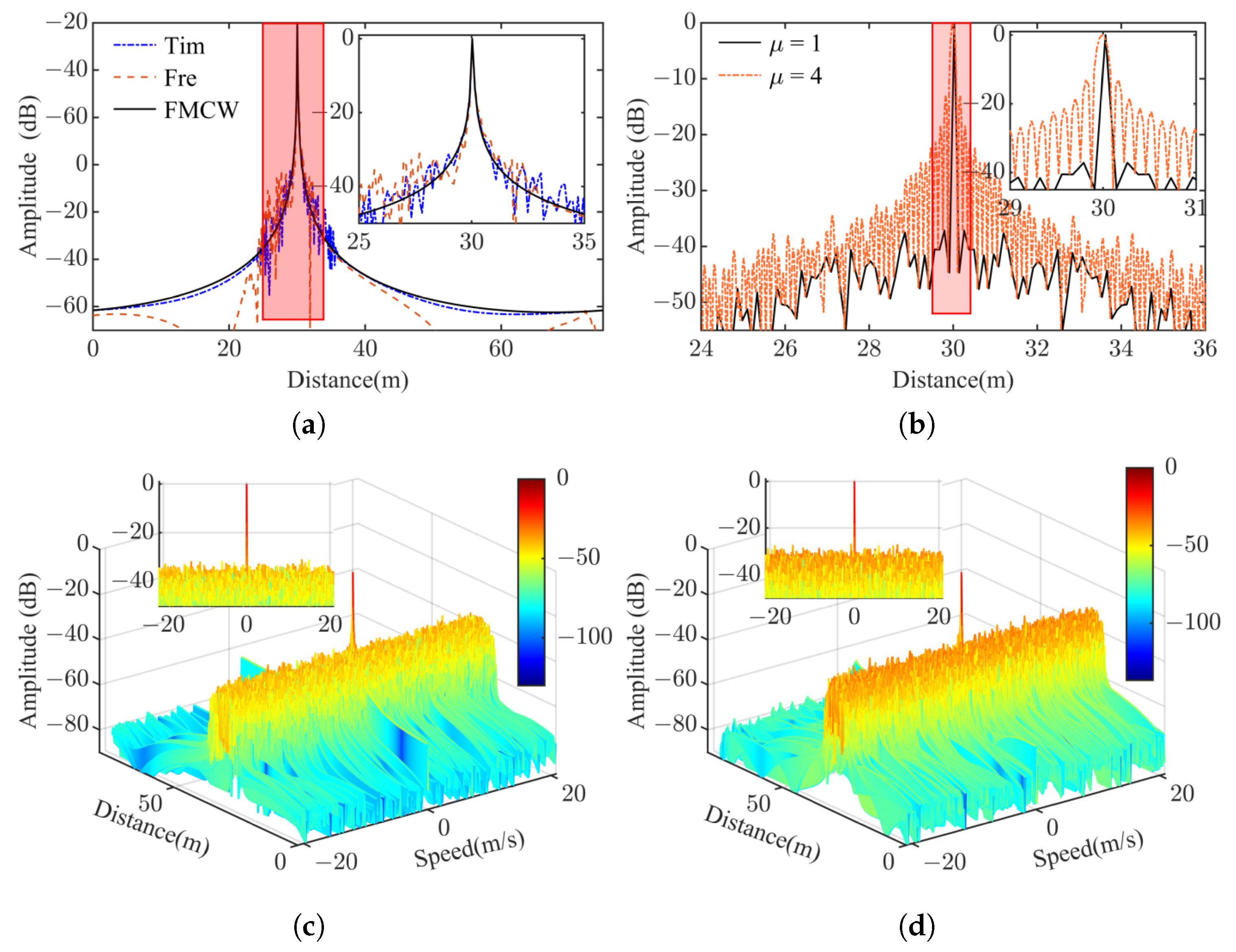

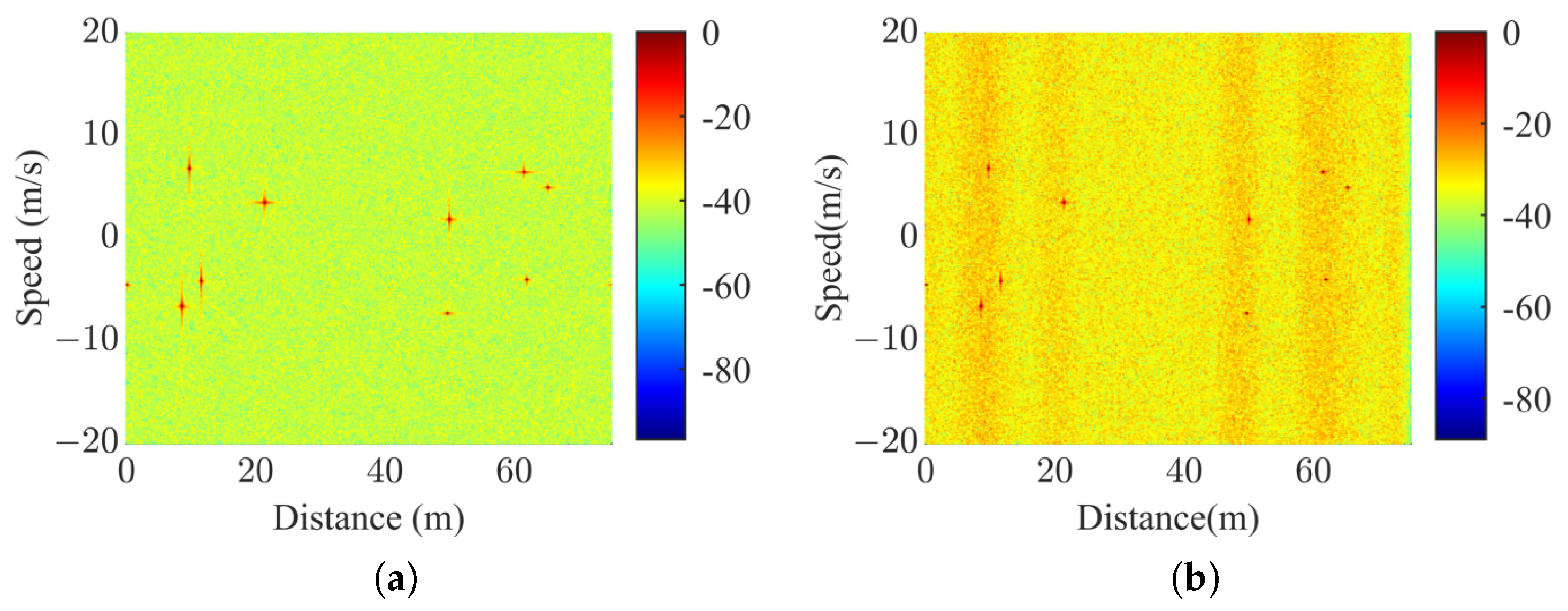

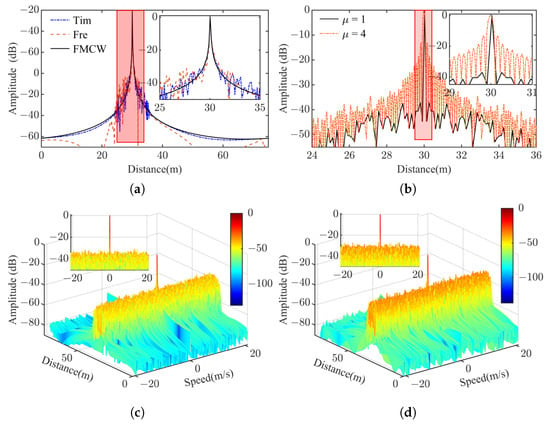

Based on the time-domain and frequency-domain pulse compression methods proposed in Section 2, a comparison of the pulse compression results between the OFDM-FMCW waveform and the traditional FMCW waveform is presented. As shown in Figure 8a, it can be observed that, among the different methods, the FMCW waveform exhibits the best pulse compression performance while the frequency-domain pulse compression of the OFDM-FMCW waveform performs the worst. However, the overall difference among the three curves is not significant. Figure 8b illustrates the difference in pulse compression performance when constructing matching coefficients with varying step sizes during the time-domain pulse compression of the OFDM-FMCW waveform. It is evident that when the step size is increased fourfold relative to the range resolution, the pulse compression result more closely approximates a sinc function. Figure 8c,d depict the Moving Target Detection (MTD) results for radar detection under the time-domain and frequency-domain pulse compression methods, respectively. Due to the randomness of the phase of the OFDM transmitted data, the noise floor near the target is elevated after coherent accumulation. It can be observed that the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for the target is approximately 35 dB when using the time-domain method and around 30 dB when employing the frequency-domain method. At the location of the simulated target, the time-domain method outperforms the frequency-domain method by about 5 dB.

Figure 8.

(a) A comparison of the pulse compression outcomes for a single-point target across different waveforms and pulse compression techniques; (b) the impact of different step sizes in the construction of matching coefficients on the performance of time-domain pulse compression; (c,d) the MTD results for the OFDM-FMCW waveform under time-domain and frequency-domain pulse compression methods, respectively.

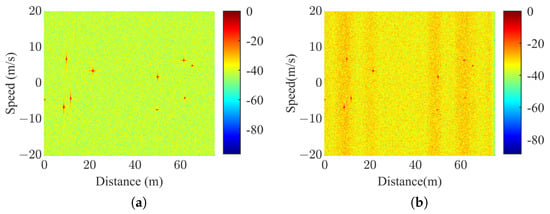

Through simulation analysis with multiple random point targets, the Range-Doppler Map (RDM) of targets under traditional FMCW and OFDM-FMCW waveforms based on the parameters in Table 1, are compared, and the results are shown in Figure 9a,b, respectively. It can be observed that, under the same echo, the RDM of the traditional FMCW has a bottom noise level approximately 10 dB lower than that of the OFDM-FMCW waveform. However, the proposed waveform structure exhibits a better pin effect for target peaks.

Figure 9.

(a) The RDM of a Traditional FMCW Waveform; (b) the RDM of a Proposed OFDM-FMCW Waveform.

It should be noted that, in our simulation analysis, we have overlooked the practical engineering issue of transmission leakage into the reception channel. Traditional FMCW radars typically employ high-pass filters in their reception channel baseband to eliminate low-frequency signals introduced by transmission leakage, a method that is not applicable in OFDM-FMCW systems. To address the problem of transmission leakage into the reception channel, it is necessary to ensure, from a hardware design perspective, that the transmission and reception channels have good isolation to prevent the leakage signals from saturating the reception channel. From the perspective of signal processing, there are various methods to eliminate this fixed coherent interfering signal, with the simplest approach being the implementation of coherent cancellation. Further research is needed to have these hardware design and signal processing techniques to work in practice across different operating conditions, varying across temperatures, etc.

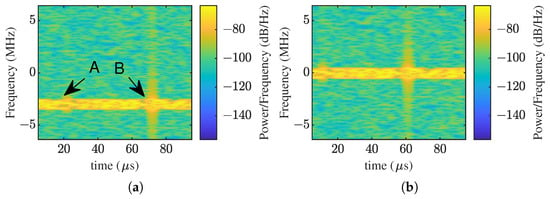

4.2. Communication System Simulation

After downconversion by the communication receive end’s local oscillator, based on the analysis in Section 3.1, an OFDM baseband signal with a frequency offset of is obtained. Figure 10a is the time-frequency diagram of the baseband signal after two consecutive chirps are downconverted at the communication receive end with a signal-to-noise ratio of 20dB. Point A in the figure corresponds to the phase jump position at time in Figure 6 due to the alternation of chirps at the transmit end, corresponding to the phase change quantity shown in (34). The reason why there is no phase jump at in Figure 6 (at in Figure 10a) is because and have an integer multiple relationship. Point B in the figure is the echo phase jump point in the next chirp of the receive local oscillator, hence the time interval between points A and B is . Figure 10b is the time-frequency diagram after rough and fine CFO estimation compensation and STO synchronization, at which point the signal only has channel errors. In the CFO rough estimation process, the spectrum of a single symbol and the waveform based on spectrum envelope matching are shown in Figure 11. It can be seen that the minimum value position of the envelope-matching curve corresponds exactly to the starting position of the spectrum protection band. In the simulation analysis, fine CFO estimation, STO estimation, and channel estimation, respectively employed the CFO estimation based on CP, STO time-domain estimation based on CP, and channel estimation based on training symbols, as described in [25].

Figure 10.

(a) Comparison of Two Pulse Compression Results for Point Targets; (b) MTD Result for Point Targets.

Figure 11.

Time-Frequency Diagram of Radar Echo.

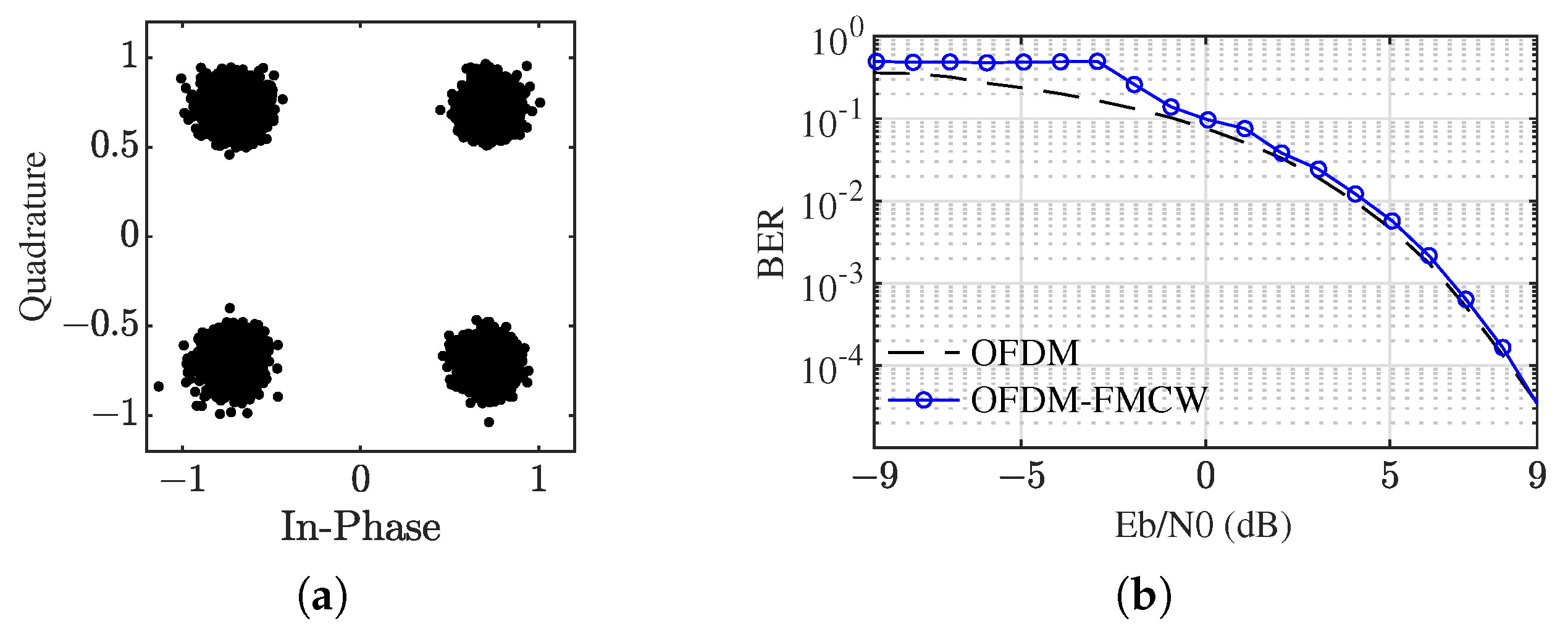

To thoroughly analyze the communication performance of OFDM-FMCW, simulations were conducted to examine the demodulation of OFDM-FMCW communication under various random transmit–receive delays, and a statistical analysis based on the Monte Carlo method was used to compare its BER curves with those of traditional OFDM waveforms. Figure 12a describes the constellation diagram of the final demodulation of the OFDM-FMCW waveform under the echo conditions of Figure 10, showing an ideal constellation diagram at this signal-to-noise ratio. Figure 12b describes the comparison of BER curves between traditional OFDM signals and OFDM-FMCW signals, indicating that, at high signal-to-noise ratios, the BER curve of the OFDM-FMCW signal is slightly worse than that of the traditional OFDM signal, but the difference is very small. This difference is primarily due to the loss introduced by the phase jump quantity (34) caused by the random synchronization position at the transmit and receive ends.

Figure 12.

(a) Constellation Diagram of OFDM-FMCW Communication Demodulation; (b) comparison of the BER Curves between OFDM-FMCW Demodulation and Traditional OFDM Demodulation.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a design for integrating OFDM with FMCW millimeter-wave radar by incorporating a transmission baseband, thereby achieving an OFDM-FMCW radar-communication integrated system. This design not only maintains the high-resolution, high-precision, and low-complexity attributes of traditional FMCW radars but also leverages the advantages of OFDM waveforms, including their diversity, robustness against interference, and high communication bandwidths. Through meticulous system modeling and analysis, we have proposed two distinct pulse compression methodologies, namely one that constructs matching coefficients in the time domain and achieves pulse compression through correlation matching via traversal and another that facilitates rapid pulse compression in the frequency domain. We compared the differences and characteristics of these methods and established the constraints for acceptable pulse compression loss in the frequency domain. By analyzing the structure of the communication receiver’s waveform, we proposed a demodulation method utilizing undersampling techniques. A systematic simulation analysis has validated the accuracy of our theoretical framework and derivations, confirming the feasibility of the proposed system structure for implementing OFDM-FMCW DFRC as an effective integrated communication and sensing solution.This approach addresses the future development needs for high performance and multifunctionality, demonstrating its potential and value across various application scenarios. Future work will concentrate on further optimizing system performance, reducing implementation complexity, and exploring the deployment and testing of this technology in more practical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, W.F.; software, J.L. and S.X.; validation, W.F.; formal analysis, J.L. and W.F.; investigation, S.X.; resources, T.S. and J.C.; data curation, S.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, W.F.; visualization, S.X.; supervision, T.S.; project administration, T.S. and J.C.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Derivation of Cross-Correlation Results

Derivation and Proof of Equation (17)

where step (a) involves expanding the convolution process ; step (b) utilizes the folding and shifting properties of convolution to interchange the order of integration; and step (c) defines the autocorrelation function .

References

- Liang, H.; Cho, J.; Seo, S. Construction Site Multi-Category Target Detection System Based on UAV Low-Altitude Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwany, E.; Mahgoub, I. Security and Trust Management in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV): Challenges and Machine Learning Solutions. Sensors 2024, 24, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, K.; Ullah, A.; Lloret, J.; Ser, J.D.; de Albuquerque, V.H.C. Deep Learning for Safe Autonomous Driving: Current Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 4316–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.Z.; Shahjalal, M.; Ahmed, S.; Jang, Y.M. 6G Wireless Communication Systems: Applications, Requirements, Technologies, Challenges, and Research Directions. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2020, 1, 957–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Tong, F.; Sun, P.; Feng, X.; Zhao, Z. Joint Design of Transmitting Waveform and Receiving Filter via Novel Riemannian Idea for DFRC System. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Zhang, J.A.; Huang, X.; Guo, Y.J. Joint Communications and Sensing Employing Multi-or Single-Carrier OFDM Communication Signals: A Tutorial on Sensing Methods, Recent Progress and a Novel Design. Sensors 2022, 22, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Liu, T.; Song, Y.; Yin, H.; Tian, B.; Zhu, N. Modified Hybrid Integration Algorithm for Moving Weak Target in Dual-Function Radar and Communication System. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, L. A Survey on Internet of Vehicles: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 4587–4599. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Fang, S.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Low-altitude intelligent transportation: System architecture, infrastructure, and key technologies. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 42, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euziere, J.; Guinvarc’h, R.; Lesturgie, M.; Uguen, B.; Gillard, R. Dual function radar communication time-modulated array. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Radar Conference, Lille, France, 13–17 October 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanie, A.; Amin, M.G.; Zhang, Y.D.; Ahmad, F. Phase-modulation based dual-function radar-communications. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2016, 10, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanien, A.; Amin, M.G.; Zhang, Y.D.; Ahmad, F. Dual-Function Radar-Communications: Information Embedding Using Sidelobe Control and Waveform Diversity. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2016, 64, 2168–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanien, A.; Amin, M.G.; Zhang, Y.D.; Ahmad, F. A dual function radar-communications system using sidelobe control and waveform diversity. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarCon), Arlington, VA, USA, 10–15 May 2015; pp. 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Shlezinger, N.; Huang, T.; Liu, Y.; Eldar, Y.C. FRaC: FMCW-Based Joint Radar-Communications System Via Index Modulation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2021, 15, 1348–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basar, E.; Wen, M.; Mesleh, R.; Di Renzo, M.; Xiao, Y.; Haas, H. Index Modulation Techniques for Next-Generation Wireless Networks. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 16693–16746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, Z. A DFRC Based on Multi-Channel and Spatial Information Fusion for Multi-Radar Communication. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 23, 1423–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wen, R.; Li, G.; Chu, C.; Wen, G. Dual-functional radar-communication based on frequency modulated continuous wave exploiting constraint frequency hopping. Signal Process. 2024, 219, 109403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A.; Vipiana, F.; Muma, M. A Survey on Radar and Communication Integration: From the Perspective of Spectrum Sharing and Coexistence. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2020, 6, 301–317. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani, M.; Beach, M.; Nix, A. Millimeter-Wave Massive MIMO for 5G Mobile Communications: Beamforming Design and Channel Measurement. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 2017, 12, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzi, S.; Colavolpe, G.; Corazza, G. On the Performance of OFDM in the Presence of Carrier Frequency Offsets and I/Q Imbalances. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2017, 65, 3017–3031. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, D.; Schweizer, B.; Knill, C.; Hasch, J.; Waldschmidt, C. MIMO-OFDM Radar Using a Linear Frequency Modulated Carrier to Reduce Sampling Requirements. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2018, 66, 3511–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Yu, G.; Xia, S.; Hu, L. A Spectrum Efficient Waveform Integrating OFDM and FMCW for Joint Communications and Sensing. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–20 May 2022; pp. 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, A.; Bonen, S.; Dadash, M.S.; Gong, M.J.; Hasch, J.; Voinigescu, S.P. 155 GHz FMCW and Stepped-Frequency Carrier OFDM Radar Sensor Transceiver IC Featuring a PLL With <30 ns Settling Time and 40 fs rms Jitter. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2021, 69, 4908–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwatt, D.S.; Lin, Y.; Ding, J.; Sun, Y.; Ning, H. Metaverse for Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS): A Comprehensive Review of Technologies, Applications, Implications, Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 6290–6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampe, J.J.V.T. MIMO-OFDM Wireless Communications with MATLAB®; Wiley-IEEE Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Chapters 1–16; p. 544. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).