The Role of Vitamin E in Immunity

Abstract

:1. Vitamin E: Definition, Structure, Sources, and Functions

1.1. Definition and Structure

1.2. Sources

1.3. Functions

2. Modulation of Immune Responses and Infectious Diseases by Vitamin E Supplementation

2.1. Immune Responses in Animals

2.2. Immune Responses in Humans

2.3. Infectious Diseases in Animals

2.4. Infectious Diseases in Humans

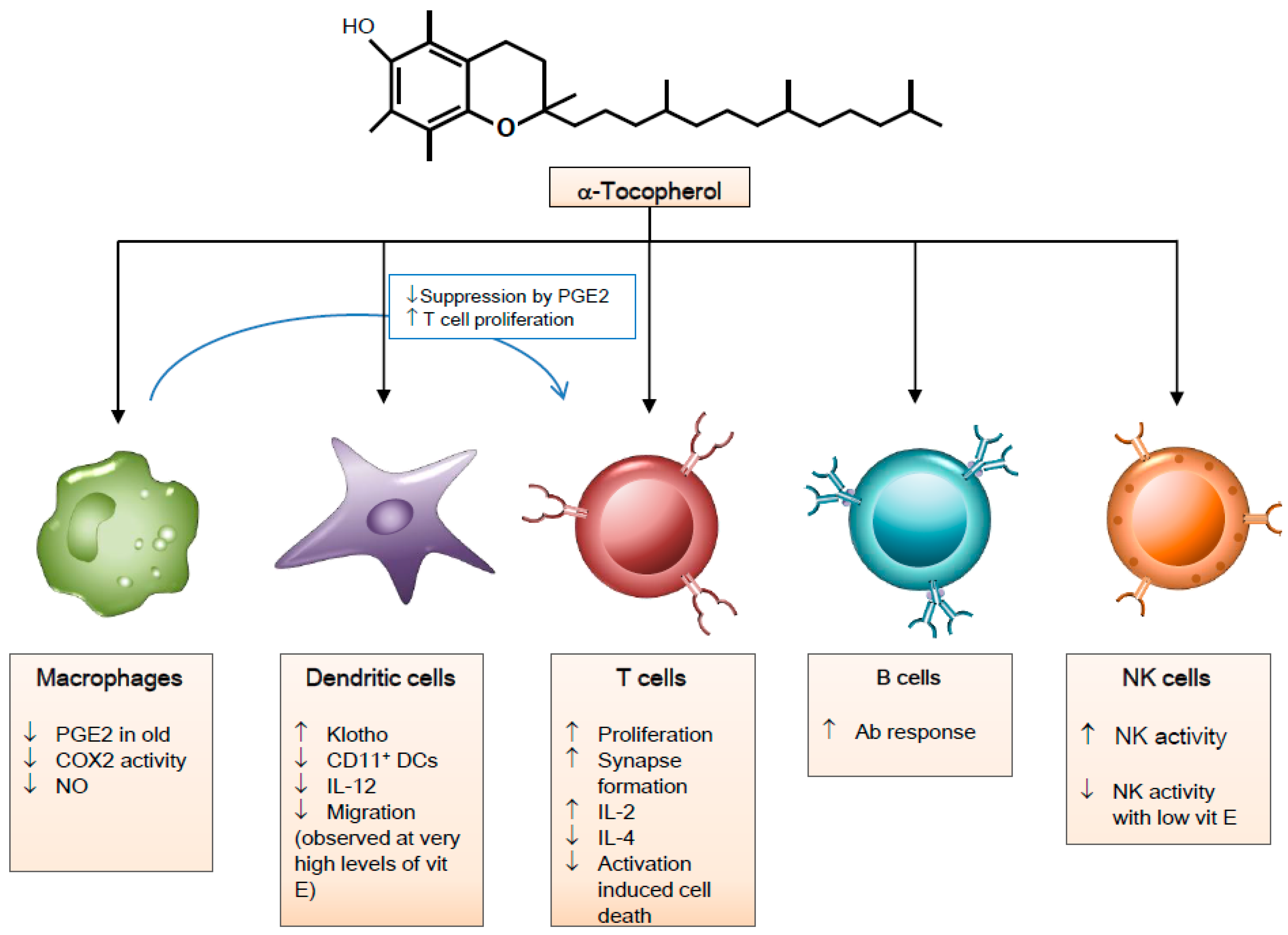

3. Vitamin E and Immune Cells

3.1. Macrophages

3.2. Natural Killer Cells

3.3. Dendritic Cells

3.4. T Cells

3.5. B Cells

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Traber, M.G. Vitamin E regulatory mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, A.J.; Pennington, J.A.T.; Weihrauch, J.L. Analysis and distribution of vitamin E in vegetable oils and foods. In Vitamin E in Health and Disease; Packer, L., Fuchs, J., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 7–65. [Google Scholar]

- Traber, M.G.; Atkinson, J. Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing m more. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingg, J.M. Vitamin E: A role in signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2015, 35, 135–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinzerling, R.H.; Tengerdy, R.P.; Wick, L.L.; Lueker, D.C. Vitamin E protects mice against Diplococcus pneumoniae type I infection. Infect. Immun. 1974, 10, 1292–1295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, S.N.; Wu, D.; Ha, W.K.; Beharka, A.; Smith, D.E.; Bender, B.S.; Meydani, S.N. Vitamin E supplementation increases T helper 1 cytokine production in old mice infected with influenza virus. Immunology 2000, 100, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayek, M.G.; Taylor, S.F.; Bender, B.S.; Han, S.N.; Meydani, M.; Smith, D.E.; Eghtesada, S.; Meydani, S.N. Vitamin E supplementation decreases lung virus titers in mice infected with influenza. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 176, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalia, A.M.; Loh, T.C.; Sazili, A.Q.; Jahromi, M.F.; Samsudin, A.A. Effects of vitamin E, inorganic selenium, bacterial organic selenium, and their combinations on immunity response in broiler chickens. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xu, X.; Su, G.; Shi, B.; Shan, A. High concentration of vitamin E supplementation in sow diet during the last week of gestation and lactation affects the immunological variables and antioxidative parameters in piglets. J. Dairy Res. 2017, 84, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, T.; Thomas, D.G.; Morel, P.C.; Rutherfurd-Markwick, K.J. Moderate dietary supplementation with vitamin E enhances lymphocyte functionality in the adult cat. Res. Vet. Sci. 2015, 99, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Pae, M.; Dao, M.C.; Smith, D.; Meydani, S.N.; Wu, D. Dietary supplementation with tocotrienols enhances immune function in C57BL/6 mice. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendich, A.; Gabriel, E.; Machlin, L.J. Dietary vitamin E requirement for optimum immune responses in the rat. J. Nutr. 1986, 116, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meydani, S.N.; Meydani, M.; Verdon, C.P.; Shapiro, A.A.; Blumberg, J.B.; Hayes, K.C. Vitamin E supplementation suppresses prostaglandin E1(2) synthesis and enhances the immune response of aged mice. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1986, 34, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakikawa, A.; Utsuyama, M.; Wakabayashi, A.; Kitagawa, M.; Hirokawa, K. Vitamin E enhances the immune functions of young but not old mice under restraint stress. Exp. Gerontol. 1999, 34, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, S.; Kobayashi, N.; Kishino, Y. High dietary intakes of vitamin E and cellular immune functions in rats. J. Nutr. 1990, 120, 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, S.; Moriguchi, S. Long-term feeding of high vitamin E diet improves the decreased mitogen response of rat splenic lymphocytes with aging. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 1997, 43, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, P.G.; Morrill, J.L.; Minocha, H.C.; Stevenson, J.S. Vitamin E is Immunostimulatory in calves. J. Dairy Sci. 1987, 70, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J.; Fujiwara, H.; Torisu, M. Vitamin E and immune response. I. Enhancement of helper T cell activity by dietary supplementation of vitamin E in mice. Immunology 1979, 38, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beharka, A.A.; Han, S.N.; Adolfsson, O.; Wu, D.; Lipman, R.; Smith, D.; Cao, G.; Meydani, M.; Meydani, S.N. Long-term dietary antioxidant supplementation reduces production of selected inflammatory mediators by murine macrophages. Nutr. Res. 2000, 20, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capó, X.; Martorell, M.; Sureda, A.; Riera, J.; Drobnic, F.; Tur, J.A.; Pons, A. Effects of Almond- and Olive Oil-Based Docosahexaenoic- and Vitamin E-Enriched Beverage Dietary Supplementation on Inflammation Associated to Exercise and Age. Nutrients. 2016, 8, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalingam, D.; Radhakrishnan, A.K.; Amom, Z.; Ibrahim, N.; Nesaretnam, K. Effects of supplementation with tocotrienol-rich fraction on immune response to tetanus toxoid immunization in normal healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, A.K.; Lee, A.L.; Wong, P.F.; Kaur, J.; Aung, H.; Nesaretnam, K. Daily supplementation of tocotrienol-rich fraction or alpha-tocopherol did not induce immunomodulatory changes in healthy human volunteers. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, J.S. Effect of vitamin E supplementation on leukocyte function. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1980, 33, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harman, D.; Miller, R.W. Effect of vitamin E on the immune response to influenza virus vaccine and the incidence of infectious disease in man. Age 1986, 9, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydani, S.N.; Barklund, M.P.; Liu, S.; Meydani, M.; Miller, R.A.; Cannon, J.G.; Morrow, F.D.; Rocklin, R.; Blumberg, J.B. Vitamin E supplementation enhances cell-mediated immunity in healthy elderly subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 52, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Waart, F.G.; Portengen, L.; Doekes, G.; Verwaal, C.J.; Kok, F.J. Effect of 3 months vitamin E supplementation on indices of the cellular and humoral immune response in elderly subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 1997, 78, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meydani, S.N.; Meydani, M.; Blumberg, J.B.; Leka, L.S.; Siber, G.; Loszewski, R.; Thompson, C.; Pedrosa, M.C.; Diamond, R.D.; Stollar, B.D. Vitamin E supplementation and in vivo immune response in healthy elderly subjects. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1997, 277, 1380–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallast, E.G.; Schouten, E.G.; de Waart, F.G.; Fonk, H.C.; Doekes, G.; von Blomberg, B.M.; Kok, F.J. Effect of 50- and 100-mg vitamin E supplements on cellular immune function in noninstitutionalized elderly persons. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Okano, T.; Tamai, H.; Mino, M. Superoxide generation in leukocytes and vitamin E. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1991, 61, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Richards, G.A.; Theron, A.J.; van Rensburg, C.E.; van Rensburg, A.J.; van der Merwe, C.A.; Kuyl, J.M.; Anderson, R. Investigation of the effects of oral administration of vitamin E and beta-carotene on the chemiluminescence responses and the frequency of sister chromatid exchanges in circulating leukocytes from cigarette smokers. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990, 142, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, T.R.; Schoene, N.; Douglass, L.W.; Judd, J.T.; Ballard-Barbash, R.; Taylor, P.R.; Bhagavan, H.N.; Nair, P.P. Increased vitamin E intake restores fish-oil-induced suppressed blastogenesis of mitogen-stimulated T lymphocytes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, D.; Han, S.N.; Meydani, M.; Meydani, S.N. Effect of concomitant consumption of fish oil and vitamin E on T cell mediated function in the elderly: A randomized double-blind trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2006, 25, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, J.G.; Meydani, S.N.; Fielding, R.A.; Fiatarone, M.A.; Meydani, M.; Farhangmehr, M.; Orencole, S.F.; Blumberg, J.B.; Evans, W.J. Acute phase response in exercise. II. Associations between vitamin E, cytokines, and muscle proteolysis. Am. J. Physiol. 1991, 260, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierpaoli, E.; Orlando, F.; Cirioni, O.; Simonetti, O.; Giacometti, A.; Provinciali, M. Supplementation with tocotrienols from Bixa orellana improves the in vivo efficacy of daptomycin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a mouse model of infected wound. Phytomedicine 2017, 36, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bou Ghanem, E.N.; Clark, S.; Du, X.; Wu, D.; Camilli, A.; Leong, J.M.; Meydani, S.N. The α-tocopherol form of vitamin E reverses age-associated susceptibility to streptococcus pneumoniae lung infection by modulating pulmonary neutrophil recruitment. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wolf, B.M.; Zajac, A.M.; Hoffer, K.A.; Sartini, B.L.; Bowdridge, S.; LaRoith, T.; Petersson, K.H. The effect of vitamin E supplementation on an experimental Haemonchus contortus infection in lambs. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 205, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, P.A.; Beck, M.A. The immune response to herpes simplex virus encephalitis in mice is modulated by dietary vitamin E. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, D.S.; Eskelson, C.D.; Watson, R.R. Long-Term Dietary Vitamin E Retards Development of Retrovirus-Induced Disregulation in Cytokine Production. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1994, 72, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, P.G.; Morrill, J.L.; Minocha, H.C.; Morrill, M.B.; Dayton, A.D.; Frey, R.A. Effect of supplemental vitamin E on the immune system of calves. J. Dairy Sci. 1986, 69, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.H.; Peck, M.D.; Alexander, J.W.; Babcock, G.F.; Warden, G.D. The effect of free radical scavengers on outcome after infection in burned mice. J. Trauma. 1990, 30, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, R.; Petro, T.M. Cellular immune response, corticosteroid levels and resistance to Listeria monocytogenes and murine leukemia in mice fed a high vitamin E diet. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1982, 393, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvedten, H.W.; Whitehair, C.K.; Langham, R.F. Influence of vitamins A and E on gnotobiotic and conventionally maintained rats exposed to Mycoplasma pulmonis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1973, 163, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stephens, L.C.; McChesney, A.E.; Nockels, C.F. Improved recovery of vitamin E-treated lambs that have been experimentally infected with intratracheal Chlamydia. Br. Vet. J. 1979, 135, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildknecht, E.G.; Squibb, R.L. The effect of vitamins A, E and K on experimentally induced histomoniasis in turkeys. Parasitology 1979, 78, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teige, J.; Tollersrud, S.; Lund, A.; Larsen, H.J. Swine dysentery: The influence of dietary vitamin E and selenium on the clinical and pathological effects of Treponema hyodysenteriae infection in pigs. Res. Vet. Sci. 1982, 32, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tengerdy, R.P.; Meyer, D.L.; Lauerman, L.H.; Lueker, D.C.; Nockels, C.F. Vitamin E-enhanced humoral antibody response to Clostridium perfringens type D in sheep. Br. Vet. J. 1983, 139, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.L.; Harrison, J.H.; Hancock, D.D.; Todhunter, D.A.; Conrad, H.R. Effect of vitamin E and selenium supplementation on incidence of clinical mastitis and duration of clinical symptoms. J. Dairy Sci. 1984, 67, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzerling, R.H.; Nockels, C.F.; Quarles, C.L.; Tengerdy, R.P. Protection of chicks against E.coli infection by dietary supplementation with vitamin E. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1974, 146, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengerdy, R.P.; Nockels, C.F. Vitamin E or vitamin A protects chickens against E. coli infection. Poult. Sci. 1975, 54, 1292–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likoff, R.O.; Guptill, D.R.; Lawrence, L.M.; McKay, C.C.; Mathias, M.M.; Nockels, C.F.; Tengerdy, R.P. Vitamin E and aspirin depress prostaglandins in protection of chickens against Escherichia coli infection. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1981, 34, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ellis, R.P.; Vorhies, M.W. Effect of supplemental dietary vitamin E on the serologic response of swine to an Escherichia coli bacterin. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1976, 168, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hemilä, H. Vitamin E administration may decrease the incidence of pneumonia in elderly males. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofin, I.O.; Spiegelman, D.; Aboud, S.; Duggan, C.; Danaei, G.; Fawzi, W.W. Supplementation with multivitamins and vitamin A and incidence of malaria among HIV-infected Tanzanian women. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 67 (Suppl. S4), S173–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, F.; Yoshida, C.; Barreto, R.; Naito, Y.; Packer, L. Oxidative-inflammatory damage in cirrhosis: Effect of vitamin E and a fermented papaya preparation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 22, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenbaek, K.; Friis, H.; Hansen, M.; Ring-Larsen, H.; Krarup, H.B. The effect of antioxidant supplementation on hepatitis C viral load, transaminases and oxidative status: A randomized trial among chronic hepatitis C virus-infected patients. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 18, 985–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meydani, S.N.; Leka, L.S.; Fine, B.C.; Dallal, G.E.; Keusch, G.T.; Singh, M.F.; Hamer, D.H. Vitamin E and respiratory tract infections in elderly nursing home residents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 292, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemilä, H.; Kaprio, J.; Albanes, D.; Heinonen, O.P.; Virtamo, J. Vitamin C, vitamin E, and beta-carotene in relation to common cold incidence in male smokers. Epidemiology 2002, 13, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemilä, H.; Virtamo, J.; Albanes, D.; Kaprio, J. Vitamin E and beta-carotene supplementation and hospital-treated pneumonia incidence in male smokers. Chest 2004, 125, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graat, J.M.; Schouten, E.G.; Kok, F.J. Effect of daily vitamin E and multivitamin-mineral supplementation on acute respiratory tract infections in elderly persons: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002, 288, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosser, D.M.; Edwards, J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meydani, S.N.; Han, S.N.; Wu, D. Vitamin E and immune response in the aged: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Immunol. Rev. 2005, 205, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beharka, A.A.; We, D.; Han, S.N.; Meydani, S.N. Macrophage prostaglandin production contributes to the age-associated decrease in T cell function which is reversed by the dietary antioxidant vitamin E. Mech. Age. Dev. 1997, 93, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, M.G.; Mura, C.; Wu, D.; Beharka, A.A.; Han, S.N.; Paulson, K.E.; Hwang, D.; Meydani, S.N. Enhanced expression of inducible cyclooxygenase with age in murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 1997, 159, 2445–2451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Mura, C.; Beharka, A.A.; Han, S.N.; Paulson, K.E.; Hwang, D.; Meydani, S.N. Age-associated increase in PGE2 synthesis and COX activity in murine macrophages is reversed by vitamin E. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 275, C661–C668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beharka, A.A.; Wu, D.; Serafini, M.; Meydani, S.N. Mechanism of vitamin E inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity in macrophages from old mice: Role of peroxynitrite. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 32, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, A. Nitric Oxide Synthase and Cyclooxygenase Pathways: A Complex Interplay in Cellular Signaling. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 2559–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworski, R.; Han, W.; Blackwell, T.S.; Hoskins, A.; Freeman, M.L. Vitamin E prevents NRF2 suppression by allergens in asthmatic alveolar macrophages in vivo. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adachi, N.; Migita, M.; Ohta, T.; Higashi, A.; Matsuda, I. Depressed natural killer cell activity due to decreased natural killer cell population in a vitamin E-deficient patient with Shwachman syndrome: Reversible natural killer cell abnormality by alpha-tocopherol supplementation. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1997, 156, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravaglia, G.; Forti, P.; Maioli, F.; Bastagli, L.; Facchini, A.; Mariani, E.; Savarino, L.; Sassi, S.; Cucinotta, D.; Lenaz, G. Effect of micronutrient status on natural killer cell immune function in healthy free-living subjects aged ≥90 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, M.G.; Ozenci, V.; Carlsten, M.C.; Glimelius, B.L.; Frödin, J.E.; Masucci, G.; Malmberg, K.J.; Kiessling, R.V. A short-term dietary supplementation with high doses of vitamin E increases NK cell cytolytic activity in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2007, 56, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiff, A.; Trikha, P.; Mundy-Bosse, B.; McMichael, E.; Mace, T.A.; Benner, B.; Kendra, K.; Campbell, A.; Gautam, S.; Abood, D.; et al. Nitric Oxide Production by Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Plays a Role in Impairing Fc Receptor-Mediated Natural Killer Cell Function. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1891–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, D.; Haak, S.; Sisirak, V.; Reizis, B. The role of dendritic cells in autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, E.J.; Everts, B. Dendritic cell metabolism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alloatti, A.; Kotsias, F.; Magalhaes, J.G.; Amigorena, S. Dendritic cell maturation and cross-presentation: Timing matters! Immunol. Rev. 2016, 272, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, P.H.; Sagoo, P.; Chan, C.; Yates, J.B.; Campbell, J.; Beutelspacher, S.C.; Foxwell, B.M.; Lombardi, G.; George, A.J. Inhibition of NF-kappa B and oxidative pathways in human dendritic cells by antioxidative vitamins generates regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 7633–7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, N.T.; Trang, P.T.; Van Phong, N.; Toan, N.L.; Trung, D.M.; Bac, N.D.; Nguyen, V.L.; Hoang, N.H.; van Hai, N. Klotho sensitive regulation of dendritic cell functions by vitamin E. Biol. Res. 2016, 49, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buendía, P.; Ramírez, R.; Aljama, P.; Carracedo, J. Klotho Prevents Translocation of NFκB. Vitam. Horm. 2016, 101, 119–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdala-Valencia, H.; Berdnikovs, S.; Soveg, F.W.; Cook-Mills, J.M. α-Tocopherol supplementation of allergic female mice inhibits development of CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cells in utero and allergic inflammation in neonates. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2014, 307, L482–L496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdala-Valencia, H.; Soveg, F.; Cook-Mills, J.M. γ-Tocopherol supplementation of allergic female mice augments development of CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cells in utero and allergic inflammation in neonates. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2016, 310, L759–L771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molano, A.; Meydani, S.N. Vitamin E, signalosomes and gene expression in T cells. Mol. Aspects. Med. 2012, 33, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolfsson, O.; Huber, B.T.; Meydani, S.N. Vitamin E-enhanced IL-2 production in old mice: Naive but not memory T cells show increased cell division cycling and IL-2-producing capacity. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 3809–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marko, M.G.; Ahmed, T.; Bunnell, S.C.; Wu, D.; Chung, H.; Huber, B.T.; Meydani, S.N. Age-associated decline in effective immune synapse formation of CD4(+) T cells is reversed by vitamin E supplementation. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marko, M.G.; Pang, H.J.; Ren, Z.; Azzi, A.; Huber, B.T.; Bunnell, S.C.; Meydani, S.N. Vitamin E reverses impaired linker for activation of T cells activation in T cells from aged C57BL/6 mice. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.N.; Adolfsson, O.; Lee, C.K.; Prolla, T.A.; Ordovas, J.; Meydani, S.N. Age and vitamin E-induced changes in gene expression profiles of T cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 6052–6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelizon, C. Down to the origin: Cdc6 protein and the competence to replicate. Trends Cell Biol. 2003, 13, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Weber, M.; Giaisi, M.; Treiber, M.K.; Krammer, P.H. Vitamin E inhibits IL-4 gene expression in peripheral blood T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002, 32, 2401–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malmberg, K.J.; Lenkei, R.; Petersson, M.; Ohlum, T.; Ichihara, F.; Glimelius, B.; Frödin, J.E.; Masucci, G. A short-term dietary supplementation of high doses of vitamin E increases T helper 1 cytokine production in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002, 8, 1772–1778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li-Weber, M.; Weigand, M.A.; Giaisi, M.; Süss, D.; Treiber, M.K.; Baumann, S.; Ritsou, E.; Breitkreutz, R.; Krammer, P.H. Vitamin E inhibits CD95 ligand expression and protects T cells from activation-induced cell death. J. Clin. Invest. 2002, 110, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Neuzil, J.; Svensson, I.; Weber, T.; Weber, C.; Brunk, U.T. α-tocopheryl succinate-induced apoptosis in Jurkat T cells involves caspase-3 activation, and both lysosomal and mitochondrial destabilisation. FEBS Lett. 1999, 445, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Dosage and Duration | Form of Vitamin E Used | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicks, female broiler (n = 6/group, 6 replicate) | 100 mg/kg diet for 21 days | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | ↑Plasma IgM levels at day 21 | Dalia et al. 2018 [8] |

| ↔Splenic expressions of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-10 | ||||

| Pregnant cows (n = 24/group) | 250 IU/day from day 107 of gestation to day 21 of lactation | NA | ↑IgG and IgA concentration in sow plasma | Wang et al. 2017 [9] |

| Domestic cats (39 castrated male and 33 intact female) (n = 8/group) | 225, 450 mg/kg diet for 28 days | α-tocopherol | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA, PHA) | O’ Brien et al. 2015 [10] |

| Young and old mice (n = 11–13/group) | 500 mg/kg diet for 6 weeks | dl-α-tocotrienol | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation in old (ConA, PHA) | Ren et al. 2010 [11] |

| ↑IL-1β production in young | ||||

| Young rats (n = 6/group) | 50, 200 mg/kg diet for 8–10 weeks | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA, LPS) | Bendich et al. 1986 [12] | |

| Old mice (n = 10/group) | 500 mg/kg diet for 6 weeks | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA, LPS) | Meydani et al. 1986 [13] |

| ↑DTH response | ||||

| ↑IL-2 production | ||||

| ↓PGE2 production | ||||

| Young and old mice (n = 5/group) | 500 IU (500 mg) for 9 weeks | dl-α-tocopherol acetate | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA) in young | Wakikawa et al. 1999 [14] |

| ↔Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA) in old | ||||

| ↑IFN-γ in young under restraint stress | ||||

| Young rats (n = 10/group) | 50, 100, 250, 500, 2500 mg/kg diet for 7 days | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (>100 mg/kg diet, ConA) (>250 mg/kg diet, LPS) | Moriguchi et al. 1990 [15] |

| ↑NK activity (>250 mg/kg diet) | ||||

| Old rats (n = 5/group) | 585 mg/kg diet for 12 months | dl-α-tocopheryl nicotinate | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA, PHA) | Sakai S & Moriguchi 1997 [16] |

| ↑IL-2 production | ||||

| Young calves (n = 8/group) | 125, 250, 500 IU (125, 250, 500 mg)/day for 24 weeks | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (PHA, ConA, pokeweed mitogen) | Reddy et al. 1987 [17] |

| ↑Antibovine herpesvirus Ab titer to booster in 125 IU/day group | ||||

| Young mice (n = 8/group) | 200 mg/kg diet for 6–12 weeks | α-tocopheryl acetate | ↑Ab response | Tanake et al. 1979 [18] |

| ↑Helper T cell activity | ||||

| Mice (n = 10/group) | 500 mg/kg diet for 6 months | α-tocopherol acetate (Tekland, Madison, WI) | ↓IL-6 and PGEs (unstimulated) production by macrophages | Beharka et al. 2000 [19] |

| ↓Nitric oxide production (LPS) by macrophages |

| Subjects | Age | Amount and Duration of Supplementation | Form of Vitamin E Used | Effects on Immune Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young (n = 5) and senior athletes (n = 5) | 18–25, 35–57 | 4.6 ± 0.3 mg/100 mL of vitamin E-enriched beverage 5 days/week for 5 weeks | α-tocopherol acetate | ↑15LOX2, TNF-α expression | Capo et al. 2016 [20] |

| Healthy women (n = 108) | 18–25 | 400 mg TRF/day for 56 days | d-α-tocotrienol | ↑IL-4 (TT vaccine), IFN-γ (ConA) | Mahalingam et al. 2011 [21] |

| d-γ-tocotrienol | |||||

| d-δ-tocotrienol | ↓IL-6 (LPS) | ||||

| d-α-tocopherol | |||||

| Healthy men and women (n = 19, 34) | 20–50 | 200 mg/day for 56 days | α-tocopherol | ↔IL-4, IFN-γ production (ConA) | Radhakrishnan et al. 2009 [22] |

| Adult males and young boys (n = 18) | 25–30, 13–18 | 300 mg/day for 3 weeks | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | ↓Lymphocyte proliferation (PHA) | Prasad 1980 [23] |

| ↔DTH | |||||

| ↓Bactericidal activity | |||||

| Institutionalized adult males and females (n = 103) | 24–104 | 200, 400 mg/day for 6 months | α-tocopherol acetate | ↔Ab development to influenza virus | Harman and Miller 1986 [24] |

| Healthy elderly males and females (n = 32) | ≥60 | 800 mg/day for 30 days | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA) | Meydani et al. 1990 [25] |

| ↑DTH | |||||

| ↑IL-2 production (ConA) | |||||

| ↓PGE2 production (PHA) | |||||

| Eldery males and females (n = 74) | ≥65 | 100 mg/day for 3 months | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | ↔Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA, PHA) | De Waart et al. 1997 [26] |

| ↔IgG, IgA levels | |||||

| Healthy elderly males and females (n = 88) | ≥65 | 60, 200, 800 mg/day for 235 days | dl-α-tocopherol | ↑DTH and antibody titer to hepatitis B with 200, 800 mg | Meydani et al. 1997 [27] |

| Healthy elderly males and females (n = 161) | 65–80 | 50, 100 mg/day for 6 months | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | ↑No. of positive DTH reaction with 100 mg | Pallast et al. 1999 [28] |

| ↑dDiameter of induration of DTH reaction in a subgroup supplemented with 100 mg | |||||

| ↔IL-2 production | |||||

| ↓IFN-γ production | |||||

| Healthy young adults (n = 31) and premature infants (n = 10) | 24–31 | 600 mg/day for 3 months40 mg/kg body weight for 8–14 days | ↓Chemiluminescence | Okano et al. 1990 [29] | |

| Cigarette smoker (n = 60) | 33 ± 4 | 900 IU/day for 6 weeks | ↓Chemiluminescence | Richards et al. 1990 [30] | |

| Healthy males (n = 40) | 24–57 | 200 mg/day for 4 months | all-rac-α-tocopherol | Prevented fish-oil-induced suppression of ConA mitogenesis | Kramer et al. 1991 [31] |

| Healthy elderly (n = 40) | >65 | 100, 200, or 400 mg/day for 3 months | dl-α-tocopherol | ↑DTH (maximal diameter) in 100, 200, 400 mg groups | Wu et al. 2006 [32] |

| ↑Lymphocyte proliferation (ConA) in 200 mg group | |||||

| Sedentary young and elderly males (n = 21) | 22–29, 55–74 | 800 IU (727 mg)/day for 48 days | dl-α-tocopherol | ↓IL-6 secretion | Cannon et al. 1991 [33] |

| ↓Exercise-enhanced IL-1β secretion |

| Subjects | Age | Dose and Duration of Supplementation | Form of Vitamin E Used | Infection Organism and Route of Infection | Results: Effects of Vitamin E Supplementation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice BALB/c (n = 3–6/group) | 6 months | 100 mg/kg for 8 days before MRSA-challenge | δ-, γ-Tocotrienol | MRSA, inoculated onto superficial surgical wounds | Higher NK cytotoxicity | Pierpaoli et al. 2017 [34] |

| Higher IL-24 mRNA expression levels | ||||||

| Young and aged male mice C57BL/6 (n = 6/group) | 2, 22–26 months | 500 mg/kg for 4 weeks prior to infection | d-α-tocopheryl acetate | Streptococcus pneumoniae, intra-tracheally injected | 1000-fold fewer bacteria in their lung | Bou Ghanem et al. 2015 [35] |

| Age-associated higher production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-, IL-6) were reduced | ||||||

| 3-fold reduction in the number of PMNs | ||||||

| Worm-free lambs (n =10/group) | 28–32 weeks | 5.3 IU (3.56 mg)/kg BW for 12 weeks | d-α-tocopherol | H. contortus L3 larvae, route NA | No difference in serum IgG or peripheral mRNA expression of IL-4 or IFN-γ | De Wolf et al. 2014 [36] |

| Lower PCV, FEC, and worm burden | ||||||

| Male mice BALB/c (n = 6–7/group) | At weaning | Deficient, Adequate (38.4 mg/kg diet), or Supplemented (384 mg/kg diet) for 4 weeks | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | HSV-1, intranasally | Higher viral titre and ILβ, TNF-α, RANTES in the brain with E deficiency | Sheridan & Beck. 2008 [37] |

| No difference in expressions of IL-6, TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-10 between adequate and supplemented | ||||||

| Mice C57BL (n = 6–9/group) | 22 months | 500 mg/kg diet for 8 weeks | dl-α-tocopherol acetate | Influenza by nasal inoculation | Lower viral titer | Han et al. 2000 [6] |

| Higher IL-2 and IFN-γ production | ||||||

| Mice, C57BL/6 (n = 4–9) | 22 months | 500mg/kg diet for 6 weeks | dl-α-tocopherol acetate | Influenza A/PC/1/73 (H3N2) by nasal inoculation | Lower viral titre | Hayek et al. 1997 [7] |

| Mice, C57BL/6 (n = 6) | 5 weeks | 160 IU/L liquid diet for 4, 8, 12, 16 weeks | all-rac-α-tocopheryl acetate | Murine LP-BM5 leukaemia retrovirus by IP injection | Restored IL-2 and IFN-γ production by splenocytes following infection | Wang et al. 1994 [38] |

| Calves, Holstein (n = 7) | 1d | 1400 or 2800 mg orally once per week, 1400 mg injection once per week for 12 weeks | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Bovine rhinotracheitis virus, in vitro | Serum from vitamin E-supplemented calves inhibited the replication of bovine rhinotracheitis virus in vitro | Reddy et al. 1986 [39] |

| Mice, Swiss Webster (n = 10) | 4 weeks | 180 mg/kg diet for 4 weeks | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Diplococcus pneumoniae type I by IP injection | Higher survival | Heinzerling et al. 1974a [5] |

| Mice, BALB/C (n = 25) | NA | 25 or 250 mg/kg bw orally for 4 days, starting 2 days before burn injury | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, subeschar injection to burned mice | Lower mortality rate | Fang et al. 1990 [40] |

| Mice, BALB/C (NA) | 3 weeks | 4000mg/kg diet for 2, 4, or 14 weeks | Vitamin E injectable (aqueous) | Listeria monocytogenes by IP injection | No difference in resistance | Watson & Petro 1982 [41] |

| Rats, Sprague-Dawley (n = 6) | 3 weeks | 180 mg/kg diet + 6000 IU vitamin A/kg diet for 6 weeks | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Mycoplasma pulmonis by aerosol | Higher resistance to infection | Tvedten et al. 1973 [42] |

| Lambs (n = 10) | NA | 1000 IU orally, 300 mg/kg diet for 23 days | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Chlamydia by intratracheal inoculation | Faster recovery (higher food intake and weight gains) | Stephens et al. 1979 [43] |

| Turkey, broadbreasted white poults (n = 6) | 1 day | 500 mg/kg diet for 14 days before infection and 18–21 days after infection | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Histomonas meleagridis, oral | No effect on mortality by vitamin E supplementation alone | Schildknecht & Squibb 1979 [44] |

| Lower mortality and lesion score in combination with ipronidazole | ||||||

| Pigs (n = 6) | NA | 200 mg/pig per day for 59 days before infection and 22 days after infection | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Treponema hyodysenteriae, oral | Improved weight gain and recovery rate | Teige et al. 1982 [45] |

| No beneficial effect on appetite and diarrhoea | ||||||

| Sheep (n = 12) | 3–6 months | 300 mg/kg diet starting 2 weeks before first vaccination | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Clostridium perfringens type D by IV injection after two IM vaccinations | Higher Ab titre | Tengerdy et al. 1983 [46] |

| Fail to prove beneficial effect of vitamin E on protection (none of the vaccinated lambs died) | ||||||

| Cows (n = 20) | NA | 740 mg/cow per day, duration NA | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Natural occurrence of clinical mastitis due to Streptococci, Coliform, Staphylococci, Clostridium bovis | Lower clinical cases of mastitis | Smith et al. 1984 [47] |

| Chicks, broiler (n = 12–14) | 1day | 150 mg or 300mg/kg diet for 2 weeks before infection | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Escherichia coli, orally and post-thoracic air sac | Lower mortality | Heinzerling et al. 1974b [48] |

| Higher Ab titre | ||||||

| Chicks, broiler (n = 10) | 1 day | 300 mg/kg diet for 6 weeks, starting 3 weeks before first infection | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | E. coli, post-thoracic air sac | Lower mortality | Tengerdy & Nockels 1975 [49] |

| Chicks, Leghorn (n = 22) | 1 day | 300 mg/kg diet for 4 weeks before infection | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | E. coli by IV injection | Lower mortality | Likoff et al. 1981 [50] |

| Pigs (n = 10) | 6–8 weeks | 100, 000 mg/t diet for 10 weeks, starting 2 weeks before infection | Vitamin E; Tompson-Hayward, Minneapolis, MN, USA | E. coli by IM injection | Higher serum Ab titre | Ellis & Vorhies 1976 [51] |

| Subjects | Age | Dose and Duration of Supplementation | Form of Vitamin E Used | Infection Organism and Route of Infection | Results: Effects of Vitamin E Supplementation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male smoker | 50–69 | 50 mg/d for median of 6 years | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Natural incidence of pneumonia | 69% Lower incidence of pneumonia among subgroups including participants who smoked 5–19 cigarettes per day at baseline and exercised at leisure time | Hemila et al. 2016 [52] |

| 14% Lower incidence of pneumonia among subgroups including participants who smoked ≥20 cigarettes per day at baseline and did not exercise | ||||||

| HIV-infected pregnant Tanzanian women | 25.4 | 30 mg during pregnancy (multivitamin form with 20 mg vitamins B1, 20 mg B2, 25 mg B6, 100 mg niacin, 50 μg B12, 500 mg C, and 800 μg folic acid) | NA | Natural incidence of malaria after having received malaria prophylaxis during pregnancy | Lower incidence of presumptive clinical malaria, but higher risk of any malaria parasitemia | Olofin et al. 2014 [53] |

| Patients with HCV-related cirrhosis | 54–75 | 900 IU (604.03 mg for d- or 818.18 mg for dl-)/day for 6 months | α-tocopherol | Natural incidence of cirrhosis | Reduced glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase, which are significantly lower in cirrhotic patients (p < 0.05), were comparably improved by vitamin E regimens | Marotta et al. 2007 [54] |

| Patients with chronic HCV | 18–75 | 945 IU (634.23 mg)/day for 6 months with 500 mg ascorbic acid and 200 μg of selenium | d-α-tocopherol | Natural incidence of HCV | No difference in median log plasma HCV-RNA | Groenbak et al. 2006 [55] |

| Nursing home residents | >65 | 200 IU/day for 1 year | dl-α-tocopherol | Natural incidence of respiratory infections | Fewer numbers of subjects with all and upper respiratory infections | Meydani et al. 2004 [56] |

| Lower incidence of common cold | ||||||

| No effect on lower respiratory infection | ||||||

| Male smokers | 50–69 | 50 mg/day during 4-year follow-up | α-tocopherol | Natural incidence of common cold episodes | Lower incidence of common cold | Hemila et al. 2002 [57] |

| Reduction was greatest among older city dwellers who smoked fewer than 15 cigarettes per day | ||||||

| Male smokers | 50–69 years | 50 mg/day for median of 6.1 years | dl-α-tocopheryl acetate | Natural incidence of pneumonia | No overall effect on the incidence of pneumonia. | Hemila et al. 2004 [58] |

| Lower incidence of pneumonia among the subjects who had initiated smoking at a later age (>21) | ||||||

| Non-institutionalized individuals | >60 years | 200 mg/day for median of 441 days | α-tocopherol acetate | Natural incidence and severity of self-reported acute respiratory tract infections | No effect on incidence and severity of acute respiratory tract infections | Graat et al. 2002 [59] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, G.Y.; Han, S.N. The Role of Vitamin E in Immunity. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111614

Lee GY, Han SN. The Role of Vitamin E in Immunity. Nutrients. 2018; 10(11):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111614

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ga Young, and Sung Nim Han. 2018. "The Role of Vitamin E in Immunity" Nutrients 10, no. 11: 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111614

APA StyleLee, G. Y., & Han, S. N. (2018). The Role of Vitamin E in Immunity. Nutrients, 10(11), 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111614