Abstract

The increasing recognition of sarcopenia, the age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function (muscle strength and physical performance), as a determinant of poor health in older age, has emphasized the importance of understanding more about its aetiology to inform strategies both for preventing and treating this condition. There is growing interest in the effects of modifiable factors such as diet; some nutrients have been studied but less is known about the influence of overall diet quality on sarcopenia. We conducted a systematic review of the literature examining the relationship between diet quality and the individual components of sarcopenia, i.e., muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance, and the overall risk of sarcopenia, among older adults. We identified 23 studies that met review inclusion criteria. The studies were diverse in terms of the design, setting, measures of diet quality, and outcome measurements. A small body of evidence suggested a relationship between “healthier” diets and better muscle mass outcomes. There was limited and inconsistent evidence for a link between “healthier” diets and lower risk of declines in muscle strength. There was strong and consistent observational evidence for a link between “healthier” diets and lower risk of declines in physical performance. There was a small body of cross-sectional evidence showing an association between “healthier” diets and lower risk of sarcopenia. This review provides observational evidence to support the benefits of diets of higher quality for physical performance among older adults. Findings for the other outcomes considered suggest some benefits, although the evidence is either limited in its extent (sarcopenia) or inconsistent/weak in its nature (muscle mass, muscle strength). Further studies are needed to assess the potential of whole-diet interventions for the prevention and management of sarcopenia.

1. Introduction

Sarcopenia is now widely recognised, consisting of a loss of skeletal muscle mass and physical function (muscle strength or physical performance) that occurs with advancing age [1,2,3]. It is associated with physical disability, poor quality of life and increased mortality in older adults [2] and with significant financial costs, having been estimated to increase hospitalization costs by 34% for patients aged 65 years and over [4]. Although a loss of muscle mass and decline in physical function may be expected with ageing, there is variation in the rates of decline across the population [5]. This indicates that modifiable behavioural factors such as diet could influence the development of sarcopenia. As poor diets and nutritional status are commonly reported [6,7,8,9], improving diet and nutrition may be effective for both prevention and treatment of this condition, and promoting health in later life [10].

There is significant interest in the role of dietary patterns and the effects of whole diets in predicting health, in order to take account of the collinearity between foods and nutrients and the effects of complex interactions between food constituents. The term “diet quality” is broadly used to describe how well an individual’s diet conforms to dietary recommendations and to describe how “healthy” the diet is [11,12]; often identified using principal component or factor analysis, it also includes a-priori-defined patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet. Despite using different assessment methods, there are commonalities across diet quality measures, as the “healthiness” of diets is characterised by similar foods [13]. When compared with poorer diet quality, better diet quality is characterised by higher intake of beneficial foods (e.g., fruit and vegetables, whole grains, fish, lean meat, low-fat dairy, nuts, and olive oil), but lower in energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods (e.g., refined grains, sweets and animal products that are high in saturated fats) [11,13].

Higher diet quality in older adults has been linked with various health outcomes, including to a reduced risk of common age-related diseases and to greater longevity. In general, adherence to diets of better quality, assessed by different dietary indices or a “prudent”/healthy dietary pattern, is associated with beneficial health effects; better quality diets are associated with significantly reduced risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and neurodegenerative disease, as well as reduced mortality in cancer survivors [14,15,16,17].

Less is known about the influence of diet quality on sarcopenia (muscle mass and physical function) in older age, although there is a growing evidence base linking “healthier” diets with greater muscle strength and better physical performance outcomes in older adults [10,18]. However, much of this evidence is cross-sectional. A recent systematic review on the relationship between diet quality and successful ageing [19] concluded that with regards to physical function, there were too few longitudinal studies to draw firm conclusions, although there is growing evidence of benefits of greater adherence to a Mediterranean diet [20,21]. To the best of our knowledge no reviews have collated studies, using different definitions of diet quality, to examine effects on sarcopenia. The aim of this systematic review was to bring this evidence together and to assess the relationship between diet quality and muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance, and sarcopenia, among older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

We used the methods recommended by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), University of York [22] and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [23]. The study protocol was registered on 17 January 2017, with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, registration number CRD42017047597.

2.1. Literature Search and Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible studies were those that reported a relationship between overall diet quality and a measure of muscle mass and/or physical function in older adults. Studies were included which met criteria in terms of the sample of people investigated, the exposure, the outcomes and the study design.

To be included in this review, studies were required to meet the following criteria: (1) be published in a peer-reviewed journal, with full-text availability in English; (2) the study participants were aged 50 years or older, or aged 50 years or older at study baseline for longitudinal studies (in order for a study to be included in this review, all participants needed to be over 50 years), and we included studies concerning specific patient groups such as overweight older adults or those with type 2 diabetes; (3) the study reported an analysis of the relationship between diet quality as measured using dietary patterns (including a priori dietary indices or a posteriori (or data-driven) methods [11]), or a measure of dietary variety, and an appropriate outcome measure as specified below; or an intervention study that reported the effect of following recommendations for a “healthy” diet (leading to improvements in the overall quality of diet) on an appropriate outcome measure; (4) the study included at least one physical function outcome measure of the following: muscle mass, muscle strength, physical performance, or sarcopenia (see Table 1 for further details); (5) observational studies (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional), as well as randomised controlled trials with relevant data. The exclusion criteria included: (1) the study included age groups younger than 50 years; (2) the study combined diet quality with other lifestyle measures into a “lifestyle score” (except where associations with diet quality was reported separately); (3) the study evaluated intake of individual nutrients or single foods or food groups only; (4) the study only included a subjective measure of the physical function outcome, with no objective measure available; (5) the study outcome was protein synthesis, muscle fibre hypertrophy or biochemical properties of muscle.

Table 1.

Types of measures considered for relevant outcomes, namely muscle mass, strength, physical performance, and sarcopenia.

2.1.2. Search Strategy

An information specialist provided assistance in generating relevant search terms and performing the literature search. Eight databases, namely MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, CINAHL, AMED, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and DARE via Cochrane Library, were searched for relevant articles using both MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and free-text terms related to diet quality and muscle outcomes. A sample of the search strategy and search terms that were used for this research (applied in the MEDLINE database) are detailed in a supplementary table (see Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials published online). The search terms (including terms relating to ageing) were combined using Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR”), and filters were used to limit the results to those in the English language and in humans. The search was performed in August 2016 and no date restrictions were applied. We considered studies conducted in any part of the world and the setting was noted during the data extraction process.

2.2. Study Selection

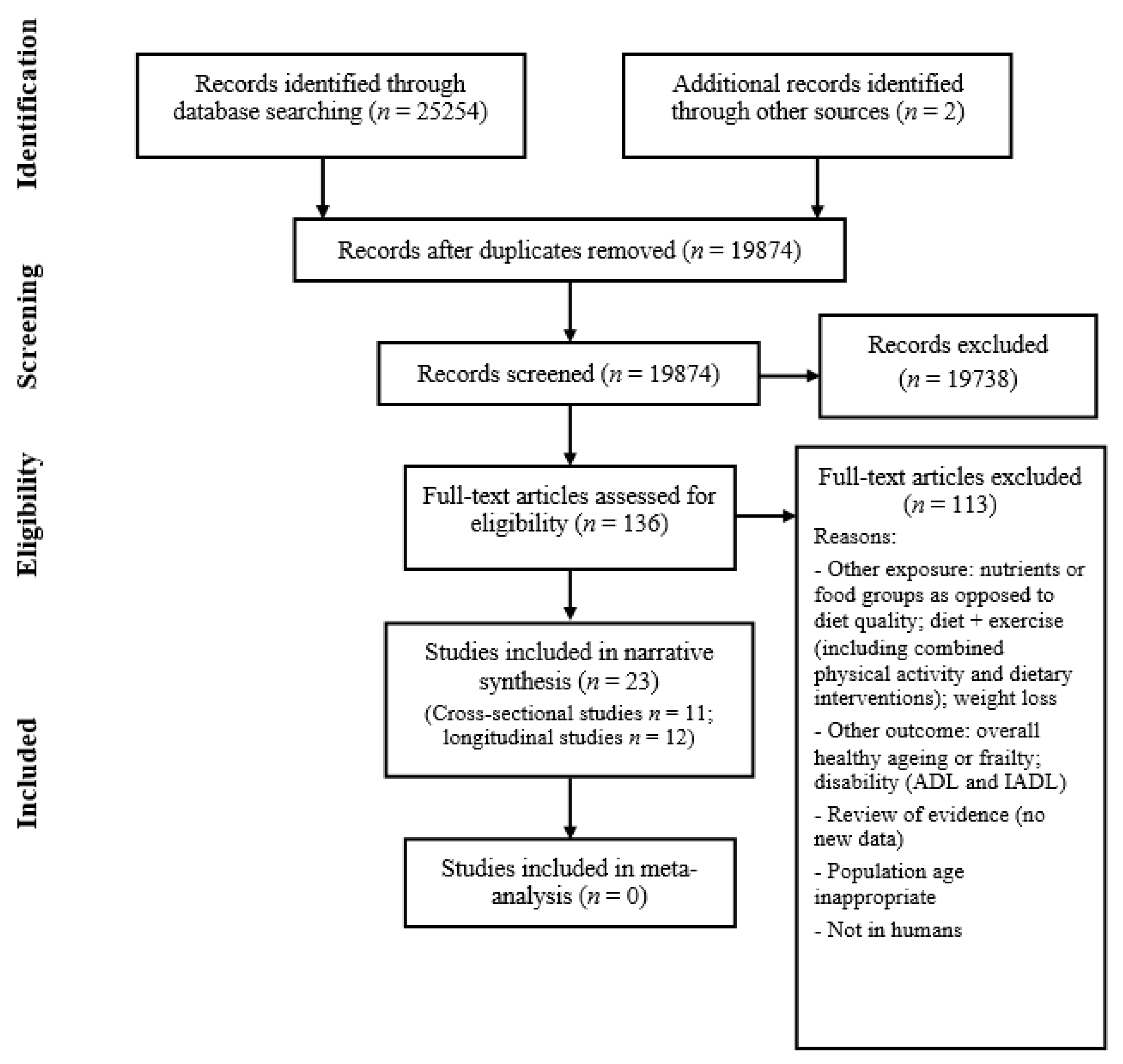

Figure 1 shows how studies were identified and selected for inclusion in the review. The database search yielded 25,254 results and discussions with experts, followed by hand searching, yielding another two studies. A total of 5382 duplicate articles were removed, leaving a total of 19,874 articles to screen titles and abstracts. Two authors (I.B. and C.S.) independently screened these records with 19,738 articles being excluded at this stage. Full-text articles were retrieved for 136 records and both authors assessed these for eligibility. This led to the identification of 23 papers which were eligible for inclusion in the review. In cases of disagreement about a study’s suitability, a third author (J.B.) was consulted. I.B. and C.S. also screened the reference lists of the included papers for any further potentially relevant articles, although none were found.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram summary of articles identified in search and showing the selection of studies for inclusion in the review.

2.3. Data Extraction and Assessment of Risk of Bias

The two reviewers, I.B. and C.S., working independently, extracted relevant data from each included article and assessed risk of bias using established criteria for observational studies, following the methods recommended by the CRD and adapted from a standard assessment tool [24]. The form was piloted on the included studies. The reviewers assessed the risk of bias of each study in relation to the review question using a set of 10 criteria, and recorded the results electronically (see Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials published online for details on the criteria and scoring system used to assess risk of bias of studies included in this review). These addressed areas including study setting, design and population, whether the exposure and outcome measurements were reliably obtained, losses to follow-up and the appropriateness of analyses presented. Regarding the confounding factors adjusted for in the analyses, we decided a priori which were important and assessed studies on the basis of how many of these were adjusted for in the analyses (the following factors were considered as important confounding factors: age, gender, physical activity, ethnicity, socioeconomic status/education, co-morbidities, smoking status). I.B. and C.S. independently carried out the quality assessment of each paper, and any discrepancies in scoring were resolved by mutual discussion or through discussion with J.B. An overall risk of bias rating was assigned to each study based on the quality score; studies were classified as either “high risk” (total score −9 to −3); “medium risk” (−2 to +3); or “low risk” of bias (+4 to +10) (see Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials for further details).

2.4. Data Synthesis

We carried out a narrative synthesis of study findings and considered the scope for meta-analysis.

3. Results

Twenty-three studies met review inclusion criteria. Studies are grouped according to outcome in Table 2 and their characteristics are shown in Table 3, also presented by outcome, first describing longitudinal and then cross-sectional studies. There were 11 cross-sectional and 12 longitudinal studies. Sample sizes ranged from 98 to 5350 participants. Almost half of the studies (n = 11) had over 1000 participants. Most studies (n = 21) were set in the community, with one set in a nursing home and another including participants from either the community or care facilities. Most of the studies (n = 16) had participants whose mean age ranged between 65 and 75 years, with five studies featuring mean ages > 75 years and only two studies having participants whose mean age was below 65 years.

Table 2.

Summary of systematic review studies by outcome.

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

Diet quality as an exposure was measured using different methods. Eight studies used a posteriori or data-driven methods, namely principal component analysis or factor analysis [25,26,27,28,29,30], and cluster analysis [31,32], to assess diet quality. Seventeen of the included studies included a priori measures of diet quality (i.e., diet indices) [26,29,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]; 15 different diet indices were used (Table 3) (dietary variety score, n = 1; fruit and vegetable variety score, n = 1; Mediterranean-type diet score (mMedTypeDiet), n = 1; Canadian Healthy Eating Index (C-HEI), n = 1; Dietary Variety Score (DVS), n = 2; Mediterranean diet score (MDS), n = 6; Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI), n = 1; Nordic diet score (NDS), n = 1; Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS), n = 1; Healthy Eating Index-2005 (HEI-2005), n = 1; alternate MED score, n = 1; Mediterranean Style Dietary Pattern Score (MSDPS), n = 1; Healthy Eating Index (HEI), n = 1; Healthy Diet Indicator (HDI), n = 1; Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I), n = 1), with four studies including multiple indices [29,33,42,47] and two studies including both indices and a posteriori methods in their analyses [26,29]. The most common a priori method used was assessment of adherence to a Mediterranean diet.

The outcomes considered, namely muscle mass, muscle strength, physical performance, and sarcopenia, were assessed using various objective tests or measurements (the outcomes considered were decided by the inclusion criteria—see Table 1). Muscle mass outcomes included appendicular lean mass (ALM) or appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM) [46]; ALM/Wt (Weight) [31]; ALM/BMI (body mass index) [34]; ALM/FM (fat mass) [34]; percentage lean mass [47]; mean arm muscle area [33]; and thigh muscle area [33]. Muscle strength outcomes included handgrip strength (most commonly assessed) [25,28,32,35,41,42,44,45,46]; knee extensor strength [35,36,43]; and elbow flexor strength [35]. Physical performance outcomes comprised walking speed (most commonly assessed) [26,28,38,40,41,42,43,44,46]; Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) [37,45,47]; Timed Up-and-Go (TUG) test [32]; chair–rise test (sit–stand chair rises) [27]; balance test [27]; and the Senior Fitness Test (SFT) battery [39]. Sarcopenia was defined in one study according to the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) algorithm [29], and in the other according to the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) criteria [30]. More than half of the studies (n = 13) used cut-off values for muscle mass, strength or function, and ten of the included studies used continuous scales to describe muscle outcomes.

Eight of the included studies were classified as having a low risk of bias in relation to our research question, while only two were deemed to have a high risk of bias (Table 2). Over half of the studies (n = 13) were classified as having a medium risk of bias (see Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials published online for a summary table of risk of bias for all studies included in the review).

The synthesis of study findings is presented by outcome in the following order: muscle mass, strength, physical performance, and sarcopenia.

3.1. Muscle Mass

Of the five studies that included muscle mass as an outcome (Table 2), four showed a positive association with diet quality. Four were cross-sectional [31,33,34,47]; none had a low risk of bias, and two had a high risk of bias [33,47]. Of the five studies, one used a posteriori methods to assess diet quality [31], and four used dietary indices or a priori measures of diet quality [33,34,46,47]. One of the studies was European [34], one was from the US [33], one was Australian [47], and two were from Asia [31,46].

A cross-sectional study [33] found that in women, a higher fruit and vegetable variety score was associated with higher mid-arm muscle area. Another cross-sectional study from Korea [31] found that a westernized dietary pattern was associated with a markedly increased abnormality of muscle mass (ASM/Wt (kg)) (authors defined abnormality of ASM/Wt as being less than the value of a young reference group, aged 20–39 years), compared to a more traditional pattern. However, no association was observed for a dietary pattern characterised by a higher consumption of meat and alcohol, and muscle mass. Another cross-sectional study [34] found that better adherence to a Mediterranean diet was associated with better muscle mass outcomes in women, but not in men. An Australian cross-sectional study [47] did not find an association between lean mass and the HEI (Healthy Eating Index) score; however, in women, there was a weak association between a higher HDI (Healthy Diet Indicator) score and higher percentage of lean mass, which disappeared when adjusted for age. The single longitudinal study [46] found that better diet quality (greater dietary variety) was not significantly associated with changes in either lean body mass or appendicular lean mass.

To summarise, there is a small body of mainly cross-sectional evidence regarding the relationship between diet quality and muscle mass, suggesting a possible relationship between healthier diets and better muscle mass outcomes in older people, especially in women. Overall, however, the evidence for an association between diet quality and muscle mass is weak, especially given the relatively lower quality of studies in this group.

3.2. Muscle Strength

Eleven of the included studies examined muscle strength as an outcome (Table 2), of which five showed a positive association with diet quality. Four were cross-sectional studies [25,43,44,45] and five had a low risk of bias [25,28,42,43,44]. Of the 11 studies, three used a posteriori methods to assess diet quality [25,28,32], and eight used a priori measures of diet quality [35,36,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Seven of the studies were European [25,28,32,41,42,44,45], two were North American [35,43], and two were from Japan [36,46].

One of the cross-sectional studies [25] found a healthier pattern of eating to be independently associated with higher handgrip strength in women but not in men. Another cross-sectional study [43] found that higher total HEI-2005 scores were associated with greater knee extension strength, however this association was no longer statistically significant after adjustment for physical activity. Two cross-sectional studies [44,45] found no statistically significant associations between higher adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern and handgrip strength. In a longitudinal study [32], dietary patterns high in red meats, potato and gravy, or butter were associated with lower grip strength and greater decline in grip strength in men, however, no association was observed in women. A longitudinal Japanese study [46] found greater dietary variety to be associated with lower risk for future declines in grip strength. Conversely, three other longitudinal studies [28,41,42] found no statistically significant associations between diet quality and handgrip strength. Another longitudinal study [35] showed no significant association between diet quality measured using the C-HEI (Canadian Healthy Eating Index) at baseline and maintenance of three measures of muscle strength. Similarly, a longitudinal study of Japanese women [36], found no significant relationship between diet quality (dietary variety) and knee extension strength.

To summarise, few studies have found positive associations between diet quality and muscle strength, and there is limited evidence for a link between “healthier” diets and lower risk of declines in muscle strength. There was a suggestion that the effects of diet on muscle strength might be different for men and women, however the evidence was inconsistent. The quality of studies was fairly good, given that almost half the studies had a low risk of bias and the others had a medium risk of bias. Overall, however, the current evidence regarding the relationship between diet quality and muscle strength is inconsistent.

3.3. Physical Performance

Of the 15 studies that looked at physical performance (Table 2), 14 showed a positive association with diet quality. Six studies were cross-sectional [27,40,43,44,45,47]; and six had a low risk of bias [28,38,39,42,43,44]. Of the 15 studies, four used a posteriori methods to assess diet quality [26,27,28,32], and 12 used a priori measures [26,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Ten of the studies were European [26,27,28,32,37,39,41,42,44,45], three of the studies were from the US [38,40,43], one was Australian [47], and one from Japan [46].

Two cross-sectional studies [40,44] found an association between higher adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern and faster walking speed (better physical performance). Another cross-sectional study [45] found that high adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern was associated with a higher SPPB score (better physical performance). A cross-sectional study [43] found that older adults with higher HEI-2005 scores had a faster walking speed, although this association was no longer statistically significant after adjustment for physical activity. On the other hand, another cross-sectional study [47] found no significant association between HEI score and SPPB score in either men or women (separately), but in men there was a weak association between a higher HDI score and better SPPB. Another study [27] did not find any independent associations between a “prudent” dietary pattern and physical performance measures. A longitudinal study [28] found that greater adherence to a “Westernized” diet pattern was associated with increased risk of slow walking speed, after a follow-up period of three and a half years. A greater adherence to a “prudent” diet pattern showed a statistically non-significant association with a lower risk of slow walking speed. Similarly, another longitudinal study [26] found that participants with greater adherence to the “Western-type” dietary pattern were more likely to have lower walking speed; the study did not find an association for the “healthy-foods” dietary pattern, or for adherence to the AHEI (Alternative Healthy Eating Index). A longitudinal study [42] found that a higher Mediterranean diet score was associated with reduced risk of slow walking after the follow-up period. Another longitudinal study [46] found that greater dietary variety was associated with lower risk for future declines in walking speed. Three other longitudinal studies [37,38,41] reported consistent associations between higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet at baseline and better physical performance (smaller decline) after follow-up periods ranging from three to nine years (in two studies, measured as walking speed, and in one using the SPPB), even when adjusting for physical activity in two of them [37,38]. In a longitudinal study [32], men with dietary patterns high in red meats and women with dietary patterns high in butter had worse physical performance (slower Timed Up-and-Go Test) than those with a “low meat” pattern, but similar rates of decline. Another longitudinal study [39] found that for women a healthy Nordic diet predicted better physical performance (SFT) at 10-year follow-up; however, no such association was observed in men.

To summarise, there is a sizeable body of longitudinal evidence regarding the relationship between diet quality and physical performance, which shows consistent evidence for a link between “healthier” diets and smaller declines in physical performance. The evidence suggests that there may be differences in the effects of diet on performance for men and women, although these gender differences were inconsistent across the studies reviewed. The quality of studies was fairly good, given that the majority of studies had a medium risk of bias and six had a low risk of bias. Overall, the current observational evidence of a positive relationship between diet quality and physical performance is strong.

3.4. Sarcopenia

Both of the studies that looked at sarcopenia (Table 2) showed an association with diet quality; one had a low risk of bias [29] and the other a medium risk of bias [30]. Both of the studies used data-driven methods to measure diet quality and one also used dietary indices [29]. A cross-sectional Iranian study [30] found that individuals with greater adherence to a Mediterranean diet pattern had a lower odds ratio for sarcopenia. A longitudinal study from China [29] found that a higher “vegetables–fruits” dietary pattern score was associated with lower likelihood of prevalent sarcopenia in older men; however, no such associations were observed in women. Although the study [29] found no association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and odds of sarcopenia, it found that a higher DQI-I (Diet Quality Index—International) score was associated with lower likelihood of prevalent sarcopenia in older men, although no such association was observed in women. Furthermore, no significant associations were found between any of the diet quality measures and four-year incident sarcopenia in either gender.

To summarise, the small body of evidence for the relationship between diet quality and sarcopenia points to a possible association between healthier diets and lower likelihood of sarcopenia in older people. There is, however, a lack of longitudinal evidence for a relationship. The quality of studies was fairly good, given that one had a low risk of bias and the other a medium risk. Overall, there is some cross-sectional evidence for a link between “healthier” diets and lower odds of sarcopenia.

We could not carry out a meta-analysis for any of the groups of studies because the definitions of both the exposure (measures of diet quality) and outcomes (measures of muscle mass, muscle strength, physical performance and sarcopenia) varied widely between studies.

4. Discussion

We systematically assessed the evidence regarding the relationship between diet quality and muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance, and sarcopenia in later life. To the best of the authors’ knowledge this is the first study to systematically review this body of evidence. We found 23 studies of older adults (≥50 years) in which the association of overall diet quality and relevant outcomes was examined. The studies were diverse in terms of the design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal, and the duration of follow-up), setting, participants included (ages varied from early old age to the very old), measures of diet quality, outcome measurements, as well as confounding factors adjusted for in the statistical models. These discrepancies could potentially contribute to some of the heterogeneity in the results.

Overall, there is a small body of mainly cross-sectional evidence suggesting a possible relationship between healthier diets and better muscle mass outcomes in older people, although, on the whole, the current evidence is fairly weak. There is limited evidence for a link between “healthier” diets and lower risk of declines in muscle strength, and overall the evidence is inconsistent. In contrast, there is a sizeable body of longitudinal evidence providing consistent evidence of a link between “healthier” diets and smaller declines in physical performance; overall, the current observational evidence for a positive relationship between diet quality and physical performance is strong. Overall, there is a small body of cross-sectional evidence pointing to a possible association between healthier diets and lower likelihood of sarcopenia in older people. There is, however, a lack of longitudinal evidence for a relationship. Some of the evidence suggests that there may be differences between men and women in terms of the effects of diet quality on both muscle strength and physical performance, although these findings were inconsistent and the overall message on differences by gender was not clear.

A recently published longitudinal study by Perälä and colleagues [52], not included in this review, provides further evidence of the benefits of diet quality for muscle strength (both grip strength and knee extensor strength). The authors found that in women, adherence to a healthy Nordic diet was associated with greater muscle strength measured 10 years later.

In general, “healthier” diets are characterised by greater fruit and vegetable consumption, greater consumption of wholemeal cereals and oily fish, which indicate higher intakes of a range of nutrients and dietary constituents that could be important for health, including for muscle function, such as higher intakes of vitamin D and n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs), higher antioxidant and protein intakes [18]. There is evidence for a link between differences in nutrient intake and status and the components of sarcopenia, with the most consistent associations found for protein, vitamin D, antioxidant nutrients and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids [18]. Protein intake has been recognised as one of the main anabolic stimuli for muscle protein synthesis [18]. There is growing evidence for benefits of supplementation with vitamin D to preserve muscle mass, strength and physical function in older age and to prevent and treat sarcopenia, and it could be that supplementation with vitamin D in combination with other nutrients might be important [18]. Sarcopenia is considered to be an inflammatory state driven by cytokines and oxidative stress; an accumulation of reactive oxygen species may lead to oxidative damage and likely contribute to losses of muscle mass and strength [10]. Omega-3 LCPUFAs have potent anti-inflammatory properties, and variations in intake could be of importance [10]. Aside from effects on inflammation, these fatty acids could also have direct effects on muscle protein synthesis [18]. “Healthier diets” are also higher in plant phytochemicals, such as polyphenols, which could have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects on muscle mass and function [18].

Although we did not find evidence for a longitudinal relationship between diet quality and sarcopenia in this review, there is evidence from a recent systematic review that better diet quality is associated with lower risk of prevalent, as well as future, frailty [53]. Nevertheless, of the 19 studies that were included in that review, only three studies examined the relationship between overall diet quality and frailty. The identification of frailty was based on the frailty phenotype described by Fried et al. [54], in two of the three studies, and on the FRAIL scale [55] in the other study. Some of the Fried frailty assessment components, namely muscle strength (grip strength) and physical performance (walking time), are common to sarcopenia. However, the FRAIL frailty scale is based on self-reported criteria (including difficulty walking), so the relationship with sarcopenia is less clear. A recent systematic review on diet quality and successful ageing [19] did not include any studies that investigated the link between diet quality measured using data-driven methods and physical function. The review did include studies that assessed the relationship between dietary indices and physical function in older adults (using both report-based and objective measures). Although there was a lack of longitudinal studies, the findings suggested a relationship between healthier diets and better physical function. Two recent systematic reviews investigated the relationship between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and musculoskeletal–functional outcomes; one focused on musculoskeletal health (including bone and muscle outcomes, specifically sarcopenia incidence or combined outcomes) in all ages [20], while the other investigated the association between a Mediterranean diet and frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia in older people [21]. The review findings indicate growing evidence of benefits of greater adherence to a Mediterranean diet, although they conclude that further research is needed to understand the relationship between a Mediterranean diet and sarcopenia and musculoskeletal health.

The studies included in the present review were all observational and most of them were from high-income countries (the majority of the studies were from countries in Europe or North America, four were from Asia, and one was from Australia). These are limitations of the current evidence-base and there is a need for more intervention studies, especially from lower-income populations, to improve our understanding of effects of diet quality on physical function. In most of the studies, diet was only assessed at one time point (baseline) therefore, any changes in diet during the follow-up period were not captured. Although different methods were used across the studies to assess dietary intake, different dietary assessment methods have been shown to define dietary patterns in a comparable manner [56,57,58]. The diversity in methods of diet quality assessment, e.g., different statistical techniques and numerous dietary indices with differing scoring approaches, should be noted; however, the core tenets of these measures are similar since the “healthiness” of diets is generally characterized by similar foods [11,13]. Around half of the included studies (n = 12) adjusted for energy intake in their analyses, and a limitation of this review is that energy intake was not considered as one of the important confounders when quality assessing the studies. A further limitation is that diverse measures of effect sizes were used across the studies, making it difficult to draw any firm conclusions about effect size (the smallest effect size for the relationship between diet quality and physical performance was a regression coefficient of 0.06 and the largest was an odds ratio of 1.85). This systematic review employed a comprehensive search strategy, in which eight databases were systematically searched, and supplemented by hand searching and contact with experts. The approach to study selection, data extraction and quality assessment followed guidance for best practice in systematic reviews, and findings are reported according to the PRISMA guidance. Another strength is that this review provides evidence for the benefits of a range of diets on musculoskeletal–functional outcomes in older people, adding to the existing evidence base that links overall diet quality with health outcomes in later life, including all-cause mortality [16,59] and chronic disease [60]. A common limitation of systematic reviews is publication bias. Although we have attempted to mitigate against this by contacting experts and hand searching, we did not identify any unpublished analyses and it remains a potential limitation of this work.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review provides observational evidence to support the importance of diets of adequate quality to protect physical performance in older age. Findings for muscle mass, muscle strength and sarcopenia are also suggestive of a link with “healthier” diets, although there are gaps in the evidence base and further studies are needed. The balance of the existing observational evidence suggests that the potential of intervention studies that take a whole-diet approach, leading to changes in intakes of a range of foods and nutrients, should be explored as strategies for the prevention and/or management of age-related losses in muscle mass and physical function. Further intervention studies are needed, especially from lower-income countries and populations, to improve our understanding of effects of diet quality on sarcopenia and its components.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/3/308/s1, Table S1: Search strategy and terms (application to the Ovid MEDLINE database); Table S2: Quality assessment form used to assess risk of bias of studies included in the review, alongside guidance notes relating to the scoring system; Table S3: Summary of scoring results in terms of risk of bias (low, medium or high) of all studies included in the review.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council and the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, a partnership between University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Southampton that is funded by the NIHR.

Author Contributions

C.C., S.R., J.B. contributed to conceptualization and methodology of this study. I.B. and C.S. performed the literature screening and data extraction and assessment of risk of bias. I.B. wrote the first draft of the article. All authors approved the final version.

Conflicts of Interest

C.C. has received lecture fees and honoraria from Amgen, Danone, Eli Lilly, GSK, Medtronic, Merck, Nestlé, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Shire, Takeda and UCB outside of the submitted work. I.B., C.S., S.R. and J.B. declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shaw, S.C.; Dennison, E.M.; Cooper, C. Epidemiology of Sarcopenia: Determinants Throughout the Lifecourse. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2017, 101, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Baeyens, J.P.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Landi, F.; Martin, F.C.; Michel, J.-P.; Rolland, Y.; Schneider, S.M.; et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayer, A.A. Sarcopenia the new geriatric giant: Time to translate research findings into clinical practice. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 736–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, A.S.; Guerra, R.S.; Fonseca, I.; Pichel, F.; Ferreira, S.; Amaral, T.F. Financial impact of sarcopenia on hospitalization costs. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodds, R.M.; Syddall, H.E.; Cooper, R.; Benzeval, M.; Deary, I.J.; Dennison, E.M.; Der, G.; Gale, C.R.; Inskip, H.M.; Jagger, C.; et al. Grip Strength across the Life Course: Normative Data from Twelve British Studies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, M.; Gunnell, D.; Ness, A.R.; Abraham, L.; Bates, C.J.; Blane, D. What influences diet in early old age? Prospective and cross-sectional analyses of the Boyd Orr cohort. Eur. J. Public Health 2006, 16, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, M.; Russell, C.A.; Stratton, R.J. Malnutrition in the UK: Policies to address the problem. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.E.; Donkin, A.J.; Morgan, K.; Neale, R.J.; Page, R.M.; Silburn, R.L. Fruit and vegetable consumption in later life. Age Ageing 1998, 27, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margetts, B.M.; Thompson, R.L.; Elia, M.; Jackson, A.A. Prevalence of risk of undernutrition is associated with poor health status in older people in the UK. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.; Cooper, C.; Aihie Sayer, A. Nutrition and sarcopenia: A review of the evidence and implications for preventive strategies. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waijers, P.M.; Feskens, E.J.; Ocké, M.C. A critical review of predefined diet quality scores. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.B. Dietary pattern analysis: A new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2002, 13, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcox, D.C.; Scapagnini, G.; Willcox, B.J. Healthy aging diets other than the Mediterranean: A focus on the Okinawan diet. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2014, 136–137, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Bogensberger, B.; Hoffmann, G. Diet Quality as Assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwedhelm, C.; Boeing, H.; Hoffmann, G.; Aleksandrova, K.; Schwingshackl, L. Effect of diet on mortality and cancer recurrence among cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, S.A.; Bates, C.J.; Mishra, G.D. Diet quality is associated with all-cause mortality in adults aged 65 years and older. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, S.A.; Dunstan, D.W.; Ball, K.; Shaw, J.; Crawford, D. Dietary Quality Is Associated with Diabetes and Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.M.; Reginster, J.Y.; Rizzoli, R.; Shaw, S.C.; Kanis, J.A.; Bautmans, I.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; Bruyère, O.; Cesari, M.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; et al. Does nutrition play a role in the prevention and management of sarcopenia? Clin. Nutr. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milte, C.M.; McNaughton, S.A. Dietary patterns and successful ageing: A systematic review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 4234–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, J.V.; Bunn, D.K.; Hayhoe, R.P.; Appleyard, W.O.; Lenaghan, E.A.; Welch, A.A. Relationship between the Mediterranean dietary pattern and musculoskeletal health in children, adolescents, and adults: Systematic review and evidence map. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 830–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.; Pizato, N.; Da Mata, F.; Figueiredo, A.; Ito, M.; Pereira, M.G. Mediterranean diet and musculoskeletal-functional outcomes in community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. 2009. Available online: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2017).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, M.; Berkman, N.D. Development of the RTI item bank on risk of bias and precision of observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, M.A.; Tucker, K.L.; Ryan, N.D.; O’Neill, E.F.; Clements, K.M.; Nelson, M.E.; Evans, W.J.; Singh, M.A.F. Higher dietary variety is associated with better nutritional status in frail elderly people. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, B.; Morais, J.A.; Dionne, I.J.; Gaudreau, P.; Payette, H.; Shatenstein, B. The combined effects of diet quality and physical activity on maintenance of muscle strength among diabetic older adults from the NuAge cohort. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 49, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Bandinelli, S.; Corsi, A.M.; Lauretani, F.; Paolisso, G.; Dominguez, L.J.; Semba, R.D.; Tanaka, T.; Abbatecola, A.M.; Talegawkar, S.A.; et al. Mediterranean diet and mobility decline in older persons. Exp. Gerontol. 2011, 46, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talegawkar, S.A.; Bandinelli, S.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Chen, P.; Milaneschi, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Semba, R.D.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. A higher adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet is inversely associated with the development of frailty in community-dwelling elderly men and women. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 2161–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Nishi, M.; Murayama, H.; Amano, H.; Taniguchi, Y.; Nofuji, Y.; Narita, M.; Matsuo, E.; Seino, S.; Kawano, Y.; et al. Dietary variety and decline in lean mass and physical performance in community-dwelling older Japanese: A 4-year follow-up study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smee, D.; Pumpa, K.; Falchi, M.; Lithander, F.E. The Relationship between Diet Quality and Falls Risk, Physical Function and Body Composition in Older Adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2015, 19, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, R.; Leung, J.; Woo, J. A Prospective Cohort Study to Examine the Association Between Dietary Patterns and Sarcopenia in Chinese Community-Dwelling Older People in Hong Kong. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, C.; No, J.K.; Kim, H.S. Dietary pattern classifications with nutrient intake and body composition changes in Korean elderly. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2014, 8, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, N.; Kim, M.; Saito, K.; Yoshida, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Hirano, H.; Obuchi, S.; Shimada, H.; Suzuki, T.; Kim, H. Lifestyle-Related Factors Contributing to Decline in Knee Extension Strength among Elderly Women: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahar, D.R.; Houston, D.K.; Hue, T.F.; Lee, J.S.; Sahyoun, N.R.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Geva, D.; Vardi, H.; Harris, T.B. Adherence to mediterranean diet and decline in walking speed over 8 years in community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1881–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Munoz, L.M.; Guallar-Castillon, P.; Lopez-Garcia, E.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F. Mediterranean diet and risk of frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, R.; Motlagh, A.D.; Heshmat, R.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Payab, M.; Yousefinia, M.; Siassi, F.; Pasalar, P.; Baygi, F. Diet and its relationship to sarcopenia in community dwelling Iranian elderly: A cross sectional study. Nutrition 2015, 31, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolov, J.; Spira, D.; Aleksandrova, K.; Otten, L.; Meyer, A.; Demuth, I.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Eckardt, R.; Norman, K. Adherence to a Mediterranean-Style Diet and Appendicular Lean Mass in Community-Dwelling Older People: Results From the Berlin Aging Study II. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.M.; Jameson, K.A.; Batelaan, S.F.; Martin, H.J.; Syddall, H.E.; Dennison, E.M.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A.; Hertfordshire Cohort Study Group. Diet and its relationship with grip strength in community-dwelling older men and women: The Hertfordshire cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbaraly, T.; Sabia, S.; Hagger-Johnson, G.; Tabak, A.G.; Shipley, M.J.; Jokela, M.; Brunner, E.J.; Hamer, M.; Batty, G.D.; Singh-Manoux, A.; et al. Does Overall Diet in Midlife Predict Future Aging Phenotypes? A Cohort Study. Am. J. Med. 2013, 126, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Munoz, L.M.; Garcia-Esquinas, E.; Lopez-Garcia, E.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F. Major dietary patterns and risk of frailty in older adults: A prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perala, M.M.; Von Bonsdorff, M.; Mannisto, S.; Salonen, M.K.; Simonen, M.; Kanerva, N.; Pohjolainen, P.; Kajantie, E.; Rantanen, T.; Eriksson, J.G. A healthy Nordic diet and physical performance in old age: Findings from the longitudinal Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granic, A.; Jagger, C.; Davies, K.; Adamson, A.; Kirkwood, T.; Hill, T.R.; Siervo, M.; Mathers, J.C.; Sayer, A.A. Effect of Dietary Patterns on Muscle Strength and Physical Performance in the Very Old: Findings from the Newcastle 85+ Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, H.; Aihie Sayer, A.; Jameson, K.; Syddall, H.; Dennison, E.M.; Cooper, C.; Robinson, S. Does diet influence physical performance in community-dwelling older people? Findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Houston, D.K.; Locher, J.L.; Ellison, K.J.; Gropper, S.; Buys, D.R.; Zizza, C.A. Higher Healthy Eating Index-2005 scores are associated with better physical performance. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbeida, M.; Goldsmith, R.; Shimony, T.; Vardi, H.; Naggan, L.; Shahar, D.R. Mediterranean diet and functional indicators among older adults in non-Mediterranean and Mediterranean countries. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 18, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollwein, J.; Diekmann, R.; Kaiser, M.J.; Bauer, J.M.; Uter, W.; Sieber, C.C.; Volkert, D. Dietary quality is related to frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fougere, B.; Mazzuco, S.; Spagnolo, P.; Guyonnet, S.; Vellas, B.; Cesari, M.; Gallucci, M. Association between the Mediterranean-style dietary pattern score and physical performance: Results from TRELONG study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2016, 20, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Smith, R.; Aulet, M.; Bensen, B.; Lichtman, S.; Wang, J.; Pierson, R.N., Jr. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass: measurement by dual-photon absorptiometry. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 52, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, S.; Watanabe, S.; Shibata, H.; Amano, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; Shinkai, S.; Yoshida, H.; Suzuki, T.; Yukawa, H.; Yasumura, S.; et al. Effects of dietary variety on declines in high-level functional capacity in elderly people living in a community. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2003, 50, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 26, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.T.; McCullough, M.L.; Newby, P.K.; Manson, J.E.; Meigs, J.B.; Rifai, N.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perälä, M.-M.; Von Bonsdorff, M.B.; Männistö, S.; Salonen, M.K.; Simonen, M.; Kanerva, N.; Rantanen, T.; Pohjolainen, P.; Eriksson, J.G. The healthy Nordic diet predicts muscle strength 10 years later in old women, but not old men. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-López, L.; Maseda, A.; De Labra, C.; Regueiro-Folgueira, L.; Rodríguez-Villamil, J.L.; Millán-Calenti, J.C. Nutritional determinants of frailty in older adults: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Cardiovascular Hlth Study, C.; Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.B.; Rimm, E.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Feskanich, D.; Stampfer, M.J.; Ascherio, A.; Sampson, L.; Willett, W.C. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed with a food-frequency questionnaire. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, S.A.; Mishra, G.D.; Bramwell, G.; Paul, A.A.; Wadsworth, M.E.J. Comparability of dietary patterns assessed by multiple dietary assessment methods: Results from the 1946 British Birth Cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crozier, S.R.; Inskip, H.M.; Godfrey, K.M.; Robinson, S.M. Dietary patterns in pregnant women: A comparison of food frequency questionnaires and four-day prospective diaries. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, D.W.; Jensen, G.L.; Hartman, T.J.; Wray, L.; Smiciklas-Wright, H. Association Between Dietary Quality and Mortality in Older Adults: A Review of the Epidemiological Evidence. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 32, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, A.K. Dietary patterns: Biomarkers and chronic disease risk. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 35, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).