4.1. Factors Impacting Consumer Acceptance of Health and Nutrition Claims

The results from this study suggest that consumers’ ability to process health and nutrition claims is impacted by a range of factors, but primarily whether the nutrient or substance is recognisable to them as being relevant or important to food or health in some way. When a claim refers to an unfamiliar nutrient, they appear to find the claim less understandable or credible.

“Doco-something, I’ve never heard of it” “I don’t understand this so if they would advertise with it I wouldn’t be convinced”.

(NL)

“They’re statements that are true but I worry about what they mean by barley beta glucans and plant steroids and plant sterols. I have no idea what they are, they could be plant fibres, plant sterols, plant steroids, I’m struggling to think what they might be”.

(UK)

“There are health claims which I cannot understand. I am not a biologist, who would know all these nutrients/substances”.

(SL)

“Plant sterols and plant stanol esters also belong to the second category. You may have noticed that I am not a chemist and do not know all these terms”.

(DE)

Also of importance in terms of consumer understanding and acceptance of health and nutrition claims, is whether the claim is recognisable as being relevant for them as an individual or for other specific population groups, and this construct was clearly reflected in the free sort strategies utilised by many of the participants across all the countries.

“Cholesterol level is for older people”.

(DE)

“Card 1, I do not know where to classify but it is also important for kids”.

(ES)

“I know that, because I also suffer from a high blood pressure”.

(DE)

“Decrease of tiredness, that is appealing because I’m tired”.

(NL)

“I’m not interested in cholesterol because I feel there is no danger for me yet”.

(SL)

It was also recognised by many participants in both their free sorting strategies and the qualitative data they provided that some of the claims presented to them lacked a stated benefit, function or effect whilst other claims did include this information and in some cases linked the nutrient with a disease.

“The ingredient is mentioned here but also there is an effect of each ingredient mentioned”.

(various cards, DE)

“No added sugar or fat-free, or rich in vitamin C, or source of Omega-3, contains wholegrain or naturally low in sodium, one of your 5 a day…. It is assumed, that the consumer knows their effects”.

(DE)

“This information does not say the benefits it provides.”

(Card 25, ES)

“The card about walnuts refers to how the product improves something”

(Card 6, NL)

“Of course, you could say something like: little sugar is good for diabetics. But that fact has not been mentioned in this claim”.

(Card 22, DE)

“One can recognize diseases here”.

(Card 12, DE)

However, it would appear to be less important for consumers if the stated function or benefit is omitted from a claim when the nutrient or substance in the claim is familiar to them, as they demonstrated that they are able to activate knowledge from previous experience to elaborate on the information given and decide based on this whether they perceive the claim to be beneficial to health, relevant for them or even credible. This process of ‘spreading activation’ suggests that claim statements have the ability to promote inferences that go beyond what is actually stated [

31,

32], although these inferences are not necessarily always correct.

“I don’t really understand these but can relate them to existing knowledge enough to take seriously, though I don’t think they’re relevant to me personally”.

(SL)

“I recently started to use vitamin B12 because someone pointed out to me that it works really well against Parkinson disease”.

(NL)

“The salt one, reducing salt, I know that’s supposed to be really good for you because it helps reduce your blood pressure”.

(UK)

“Contains wholegrain – if you eat that regularly, the risk of getting diseases is decreased.”

(DE)

“Walnuts are good for the nerves”.

(NL)

“Wholegrain, it is good for weight loss”.

(ES)

“Omega 3 is for brain, I mean not really for a brain, it is to some extent connected with problems in the stomach and problems with thought. I don’t know how to say... also fatigue, it is all connected”.

(SL)

“Sodium is good for the heart”.

(DE)

“I’ve heard this somewhere that too much calcium in the body may not affect your bone structure, but it might affect your stomach and that, you know, having too much calcium”.

(UK)

One might suggest, therefore, that the inclusion of a stated function or benefit in the claim when an unfamiliar nutrient is present may help consumers to process claims, or perhaps even minimise any potential incorrect inferences being made by consumers when a nutrient is familiar. However, our results demonstrate that by increasing the perceived level of complexity of the claim, lengthening the text or including more scientific language there is the potential to make the claim less appealing overall for many of the participants.

“The short and clear claims I find most appealing. I have to think really hard about the other claims”.

(NL)

“I believe that on these cards (cards 4 & 14) they could reduce the amount of information written”.

(SL)

In addition, a number of participants across all the countries indicated that they would be unlikely to engage with the more detailed, complex claims when shopping.

“Such long texts are obstructive. After all I want to go shopping and not reading novels”.

(DE)

“If there is a lot of writing someone who is the customer in the shop will not read it, because he does not have patience to read”.

(SL)

Conversely, some participants expressed the desire for more information, or perhaps better clarity, with respect to the nutrition claims, particularly those related to fat and sugar.

“If you find on card sentence “without fat” it does not tell you a lot; it could be good or bad for your health”.

(SL)

“We know that vitamin C is healthy, but the claim does not say it is healthy. But vitamin C is healthy. This claim does not say that it is good or bad”.

(NL)

“It’s more complicated, just “fat-free” is a bland statement”.

(UK)

Despite the shorter, less complex nutrient claims being generally described more favourably in terms of complexity, due to the lack of a stated function or benefit these claims were described by some as more likely to be promotional recommendations which invoked acceptance and credibility issues, particularly in the UK and this was also echoed in some of the other countries.

“This is just a promotion to make us buy [the product]”.

(SL)

“It is interesting to me that when I eat an orange it is rich in vitamin C. But if that is stated on a package I’m not sure if that’s really true. These things have to be stated on products in order to make them sell, it seems”.

(NL)

4.2. Consumer-Derived Typology for Nutrition and Health Claims

Our results suggest that depending on the associative networks consumers have previously formed between familiar nutrients and health benefits, they may not consciously differentiate between a nutrition claim and a health claim in the way that regulatory experts do. While this is in line with previous research [

8,

11,

12,

13,

14] the value of our research is that the MSP methodology provides rich qualitative data across a wide range of claims, providing an explanation as to why this might occur and revealing where there is greatest potential for consumer misunderstanding.

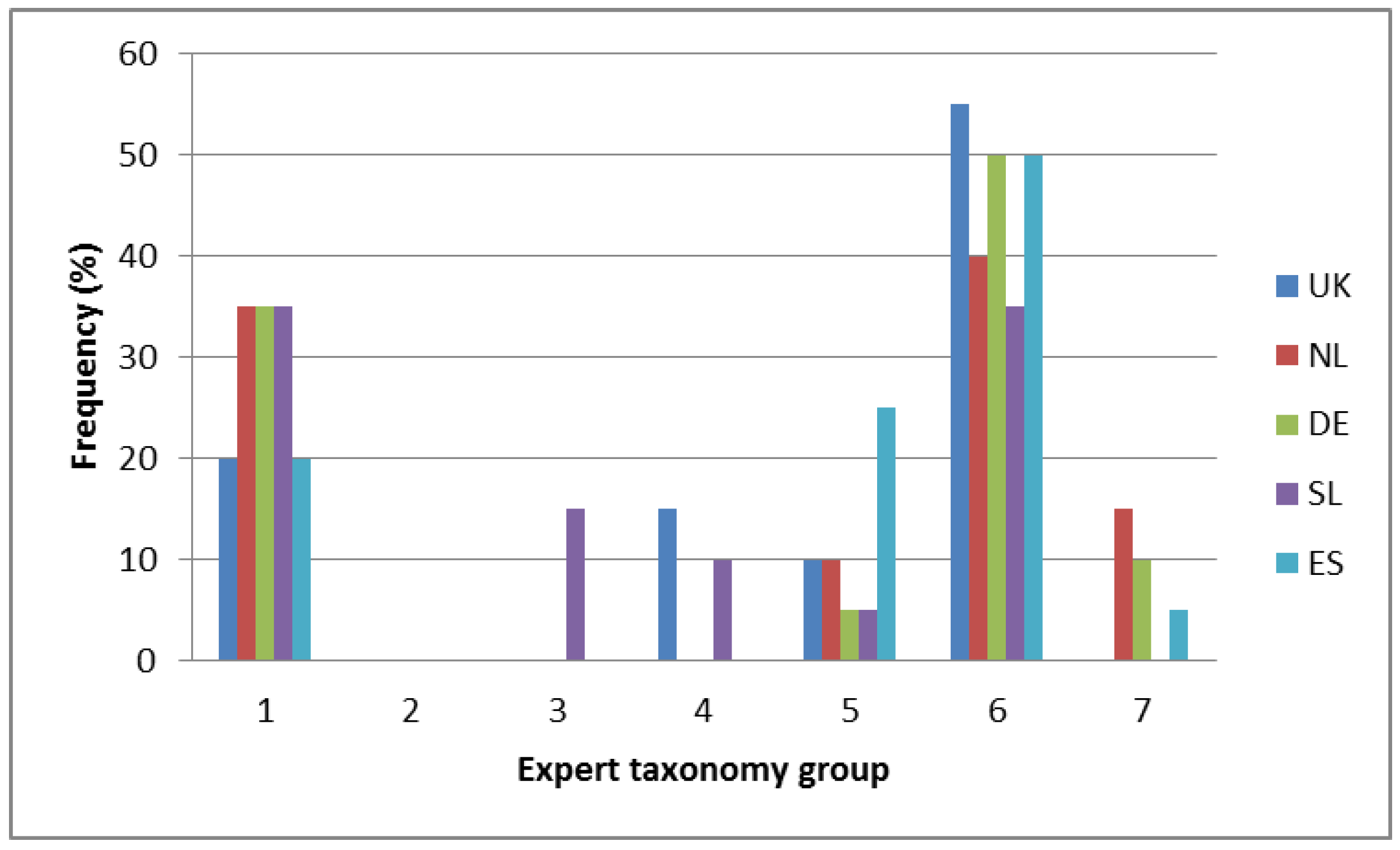

The free sorting results suggest that when categorising claims, consumers do not appear to differentiate between ‘Article 13a General function’ claims relating to growth development and functions of the body and ‘Article 14 Disease risk reduction’ claims in the way that regulatory experts do; although, in the structured sorting they were more likely to place the disease risk reduction claims under the appropriate expert typology group than they were for the Article 13a General Function claims.

Driven by how participants across the five countries categorised and made sense of the various nutrition and health claims presented in this study, we propose a typology based on three key dimensions:

Familiarity with the nutrient, substance or food stated in the claim.

Statement type in terms of its simplicity/complexity.

Relevance of the claim, either personally or for a stated population group.

Familiarity with the nutrient, substance or food stated in the claim: It has been suggested that consumer perceptions of health claims are often driven by prior beliefs about a food product or nutrient rather than by the information provided within a claim [

31]. Whether a claim contains a stated benefit or function appears to be of less importance to the consumer if they are familiar with the nutrient or functional ingredient since they appear to be able to draw on an associative network of stored knowledge and associations [

32], which they then use to make sense of the claim. It would appear from the way in which some of the claims were assigned by participants in the structured sorting task this spreading activation [

33,

34] can also lead to associations being made between a claim and a general function or the reduction of disease risk even when these were not stated in the claim. Therefore, consumer understanding or misunderstanding of nutrition and health claims, whilst affected by a number of factors, appears to be impacted primarily by their familiarity with the nutrient or substance within the claim.

“This additional information is nonsense … because everybody knows that calcium is good for bones”.

(Card 1)

Statement type in terms of its simplicity/complexity: In-line with previous research [

13,

35], our results also demonstrate that consumers perceive short and simple claims more favourably, are unlikely to engage with detailed information on the product packaging whilst shopping and are unlikely to perceive information associated with an unfamiliar nutrient positively, regardless of how detailed it is. In addition, expression of the more detailed general function claims or disease risk reduction claims utilising ‘scientific’ or ‘regulatory’ language is a problem for many consumers. Therefore, their preformed associative networks are unlikely to be formed or corrected by increasing the level or scientific basis of the information placed on the food packaging in the form of a complex claim statement. Moreover, recent research has shown that adding information to the claim does not necessarily lead to improvements in adequate understanding [

36].

Relevance of the claim, either personally or for a stated population group: In terms of consumers’ ability to assign claims to the expert typology from the NHCR within our study, it would appear that this is facilitated when the claim is deemed to be personally relevant by the consumer. Previous research has suggested that motivation to process a claim into meaningful understanding is an important factor [

8] as is how easily consumers can link the information in the claim to that which they have previously stored in their memory [

9]. In addition, Dean et al. (2012) demonstrated that relevance has a strong influence on perceptions of personal benefit and willingness to buy products with health claims [

37]. Therefore, relevance would appear to be a key factor in influencing consumer understanding, but also whether a claim is perceived favourably or not.

4.3. Policy Implications

By considering the various nutrition and health claims according to the proposed three key consumer-derived dimensions, regulatory bodies concerned with appropriate consumer understanding of health claims and stakeholders concerned with promoting consumer acceptance of health claims, can perhaps gain a deeper insight into this domain from a consumer perspective.

In terms of promoting consumer acceptance of health and nutrition claims, any claim classified as 1a/2a/3a by the proposed typology (

Table 5) is likely to be the most favourably received by consumers in that it refers to a familiar nutrient, substance or food for which the consumer has previous knowledge to draw upon. That is to say, it states the claim in a nutrient content format only, and resonates with the consumer because they perceive it to be personally relevant. In contrast, claims classified as 1b/2b/3c by this typology are likely to be the least favourably received by consumers in that they contain an unfamiliar nutrient, are complex and not easily attributable in terms of relevance to oneself or a specific population group. This perhaps explains why the claim on Card 8 ‘DHA contributes to normal brain function’ was so poorly perceived by our study participants.

Whilst claims classified by this typology as 1a/2a/3a are the most likely to be positively perceived by consumers it should be recognised that from a regulatory perspective, they also have the greatest potential to promote the process of spreading activation and possibly even the generation of incorrect inferences in consumers. The degree to which this may occur is obviously dependent on the associative networks that a consumer has previously established in relation to a particular nutrient.

In line with Ausubel’s theory of Meaningful Learning [

38], the results from our study suggest that both the associative networks and beliefs that consumers have previously developed in relation to nutrients/substances and their relationship with health outcomes, are key drivers to the way in which health claims are interpreted and understood. They also provide further evidence that consumers do not consciously differentiate between a nutrition claim and a health claim in the way that regulatory experts envision they should do. Particularly, when nutrients/substances in the claim are familiar and personally relevant there is the potential for consumers to ‘upgrade’ the former for the latter simply based on their network and prior beliefs, as opposed to what is actually stated in the claim. From a regulatory point of view, if the actual format of the claim, that is, whether it is a detailed risk reduction claim or a simple nutrition claim, is of less importance to the consumer when they have a preformed associative network for the nutrient or substance in the claim, it is then imperative that the associative networks consumers draw upon are correct and well-informed.

Our results support previous research findings that consumers perceive short and simple claims more favourably [

13,

14,

35], are unlikely to engage with detailed information on the product packaging whilst shopping and, are unlikely to perceive information associated with an unfamiliar nutrient positively, regardless of how detailed it is. In addition, they suggest that expression of the more detailed general function claims or disease risk reduction claims utilising ‘scientific’ or ‘regulatory’ language is a problem for many consumers. Therefore, these associative networks are unlikely to be formed or corrected by increasing the level or scientific basis of the information placed on the food packaging in the form of a complex claim statement. It is also important to recognise, at this point, that the removal of a claim from the packaging of a product or product category is unlikely itself, to result in consumers spontaneously readdressing their preformed associative networks regarding the benefits of that product or product category. For example, in the UK, it has been suggested that yoghurt sales have not been significantly impacted as a result of the removal of digestive health claims due to successful repositioning in terms of positive lifestyle and general wellbeing. However, it has also been suggested that this could be due, in some part, to an ‘echo chamber’ of embedded digestive health benefits within consumers previously formed associative networks [

39].

Furthermore, how aware are consumers of the relatively recent changes to the health claims legislation? It is fair to suggest that there has not been any comprehensive or structured communication to consumers on the differences between the various levels of health claims that are now permitted/not permitted and what they really mean. Regulatory bodies and those stakeholders concerned with fostering appropriate understanding of health claims in consumers should, therefore consider employing strategies to impact on this awareness in consumers, and also to impact on the associative networks consumers have previously made around particular nutrients in the nutrition and health claim domain.

For more familiar nutrients or functional ingredients where strong associative networks have been previously formed, but the claims are no longer legally allowed by the regulations, there is a need to re-educate the consumer appropriately. Similarly, for new functional ingredients, or less familiar nutrients, where associative networks have not been previously formed, there is an opportunity to educate the consumer appropriately, thus making claims for these functional ingredients potentially more appealing to consumers.

When products containing relatively unfamiliar nutrients or new functional ingredients are developed, it has been previously recognised that these need to be supported by an effective communication strategy to inform consumers of their function and benefits [

35]. In the commercial world, establishing associative networks in relevant consumer groups is a fundamental part of an effective product marketing strategy. These strategies are usually delivered in the form of magazine editorials, television advertising and more recently social media and other consumer resources accessed via the internet. Once established, the associative networks formed in consumers’ minds by these mass marketing strategies are then activated via short and consumer-tailored statements on the product packaging at point of purchase.

It is interesting to note at this point that to parallel the above commercial efforts to promote new products displaying health claims, there appears to be no authoritative information or educational resource that is independent from industry for consumers to draw upon easily. The existing EU legislation and/or the scientific literature is of little use to the lay consumer in helping them to form new, or even correct, their existing associative networks for the nutrients, functions and benefits within the health claims arena both past and present. Since two of the three main constructs identified in the proposed typology—‘familiarity’ and ‘relevance’—are constructs with individual differences, the situation is further complicated by the fact that different consumers are likely to receive the same claims differently based on their established network and beliefs.