Increasing Chocolate’s Sugar Content Enhances Its Psychoactive Effects and Intake

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Questionnaires

2.4. Anthropometric Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subjective Appetite Responses

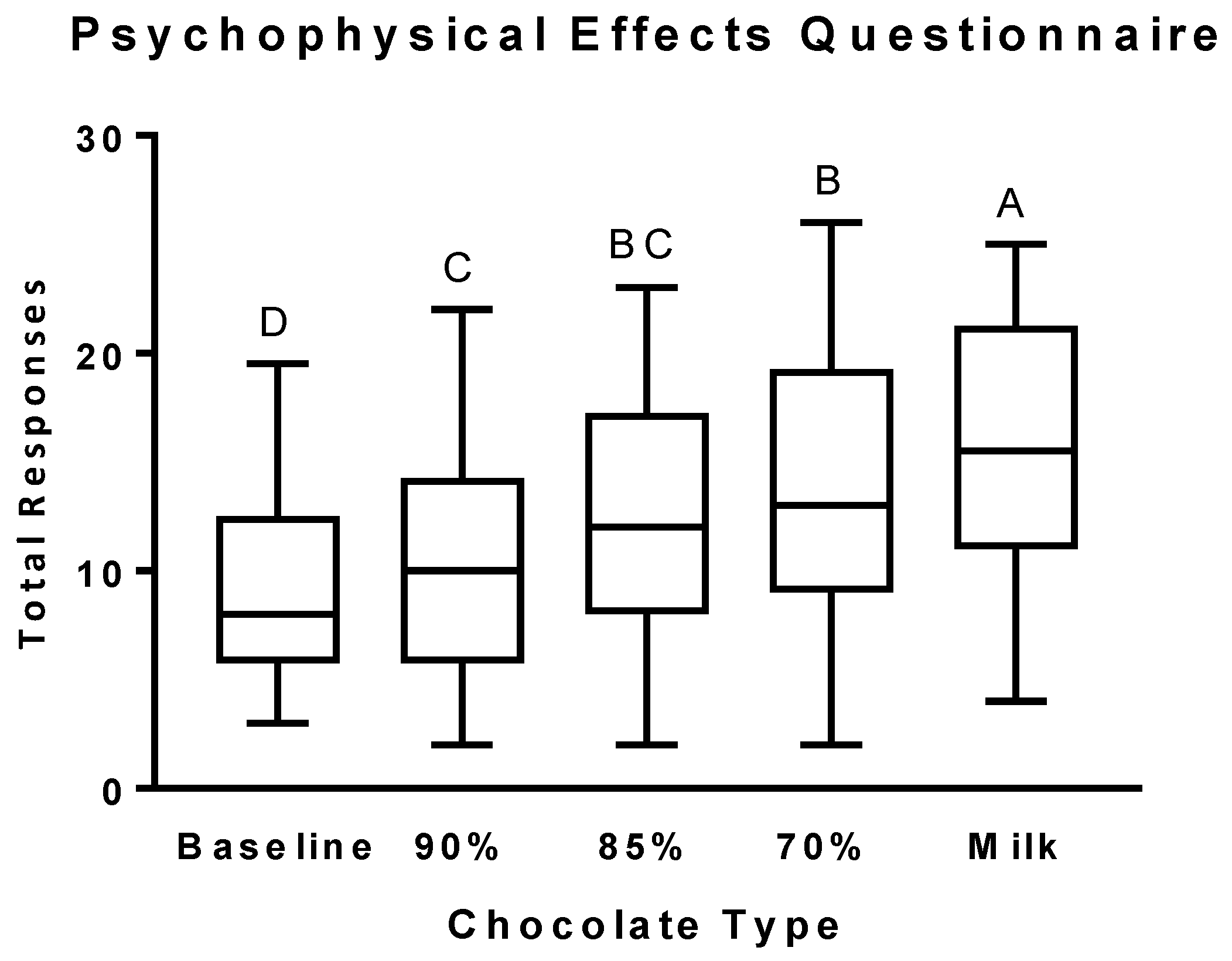

3.2. Psychophysical Effects Questionnaire

3.3. Chocolate Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schulte, E.M.; Avena, N.M.; Gearhardt, A.N. Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, M.; Dettmer, D. Everyday mood and emotions after eating a chocolate bar or an apple. Appetite 2006, 46, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, B.P.; Noll, S.W.; Molokwu, O.J. The sweet life: The effect of mindful chocolate consumption on mood. Appetite 2017, 108, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmaro, D.; Liotti, M. High-caloric and chocolate stimuli processing in healthy humans: An integration of functional imaging and electrophysiological findings. Nutrients 2014, 6, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, H.J.; Gaffan, E.A.; Rogers, P.J. Methylxanthines are the psycho-pharmacologically active constituents of chocolate. Psychopharmacology 2004, 176, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, J.A.; Bradley, L.E.; Leitzsch, J.B.; Chohan, O.; Fasulo, K.; Haller, J.; Jaeger, K.; Szulanczyk, B.; Del Parigi, A. Psychoactive effects of tasting chocolate and desire for more chocolate. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 104, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFeliceantonio, A.G.; Coppin, G.; Rigoux, L.; Edwin Thanarajah, S.; Dagher, A.; Tittgemeyer, M.; Small, D.M. Supra-additive effects of combining fat and carbohydrate on food reward. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 33–44.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, L.H.; Carr, K.A.; Lin, H.; Fletcher, K.D. Food reinforcement, energy intake, and macronutrient choice. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stice, E.; Burger, K.S.; Yokum, S. Relative ability of fat and sugar tastes to activate reward, gustatory, and somatosensory regions. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casperson, S.L.; Johnson, L.; Roemmich, J.N. The relative reinforcing value of sweet versus savory snack foods after consumption of sugar- or non-nutritive sweetened beverages. Appetite 2017, 112, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casperson, S.L.; Roemmich, J.N. Impact of dietary protein and gender on food reinforcement. Nutrients 2017, 9, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, K.C. ‘Liking’ and ‘wanting’ food rewards: Brain substrates and roles in eating disorders. Physiol. Behav. 2009, 97, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pecina, S. Opioid reward ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ in the nucleus accumbens. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 94, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, R.A. Role of brain dopamine in food reward and reinforcement. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2006, 361, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balster, R.L.; Walsh, S.L. Addiction research center inventory. In Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology; Stolerman, I.P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Haertzen, C.A. Development of scales based on patterns of drug effects, using the addiction research center inventory (arci). Psychol. Rep. 1966, 18, 163–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, E.M.; Smeal, J.K.; Gearhardt, A.N. Foods are differentially associated with subjective effect report questions of abuse liability. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, S.J.; Morris, M.J. The role of reward circuitry and food addiction in the obesity epidemic: An update. Biol. Psychol. 2018, 131, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelle, M.G.; Dieguez, C. Food addiction and binge eating: Lessons learned from animal models. Nutrients 2018, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholey, A.; Owen, L. Effects of chocolate on cognitive function and mood: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinsma, K.; Taren, D.L. Chocolate: Food or drug? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1999, 99, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Parker, I.; Brotchie, H. Mood state effects of chocolate. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 92, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massolt, E.T.; van Haard, P.M.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Posthuma, E.F.; van der Veer, E.; Schweitzer, D.H. Appetite suppression through smelling of dark chocolate correlates with changes in ghrelin in young women. Regul. Pept. 2010, 161, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, L.B.; Astrup, A. Eating dark and milk chocolate: A randomized crossover study of effects on appetite and energy intake. Nutr. Diabetes 2011, 1, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michener, W.; Rozin, P. Pharmacological versus sensory factors in the satiation of chocolate craving. Physiol. Behav. 1994, 56, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avena, N.M.; Rada, P.; Hoebel, B.G. Evidence for sugar addiction: Behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2008, 32, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Treatment for Stimulant Use Disorders; Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 33; Center for Substance Abuse Treatment: Rockville, MD, USA, 1999.

- Lee, A.A.; Owyang, C. Sugars, sweet taste receptors, and brain responses. Nutrients 2017, 9, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.Y.; McBride, R.L.; Lacy, K.E.; Keast, R.S. Psychophysical evaluation of sweetness functions across multiple sweeteners. Chem. Senses 2017, 42, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, H.R.; Cosa Linan, A.; Spanagel, R. Largely overlapping neuronal substrates of reactivity to drug, gambling, food and sexual cues: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggott, M.J.; Childs, E.; Hart, A.B.; de Bruin, E.; Palmer, A.A.; Wilkinson, J.E.; de Wit, H. Psychopharmacology of theobromine in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 2013, 228, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, H.J.; Rogers, P.J. Effects of low doses of caffeine on cognitive performance, mood and thirst in low and higher caffeine consumers. Psychopharmacology 2000, 152, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetherington, M.; Rolls, B.J.; Burley, V.J. The time course of sensory-specific satiety. Appetite 1989, 12, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.L.; Bulkley, A.M.; Badawy, R.L.; Krause, N.; McCann, S.; Epstein, L.H. Differential effects of daily snack food intake on the reinforcing value of food in obese and nonobese women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Tomasi, D.; Baler, R.D. Obesity and addiction: Neurobiological overlaps. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, L.H.; Carr, K.A.; Lin, H.; Fletcher, K.D.; Roemmich, J.N. Usual energy intake mediates the relationship between food reinforcement and bmi. Obesity 2012, 20, 1815–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.A.; Levitan, R.D.; Reid, C.; Carter, J.C.; Kaplan, A.S.; Patte, K.A.; King, N.; Curtis, C.; Kennedy, J.L. Dopamine for “wanting” and opioids for “liking”: A comparison of obese adults with and without binge eating. Obesity 2009, 17, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, J.A.; Evans, S.M.; Geliebter, A.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; Foltin, R.W. Use of an operant task to estimate food reinforcement in adult humans with and without bed. Obesity 2008, 16, 1816–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulik, C.M.; Brinded, E.C. The effect of food deprivation on the reinforcing value of food and smoking in bulimic and control women. Physiol. Behav. 1994, 55, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkovsky, P.; Veisenberger, E.; Haycock, J.W.; Akopian, A.; Garcia-Espana, A.; Meller, E. Activity-dependent phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase in dopaminergic neurons of the rat retina. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 4242–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, J.; Illiano, P.; Sotnikova, T.D.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Beaulieu, J.M.; Hebert, M. The electroretinogram as a biomarker of central dopamine and serotonin: Potential relevance to psychiatric disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Smelson, D.A.; Roy, A. Abnormal electroretinogram in cocaine-dependent patients. Relationship to craving. Br. J. Psychiatry 1996, 168, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smelson, D.A.; Roy, A.; Roy, M.; Tershakovec, D.; Engelhart, C.; Losonczy, M.F. Electroretinogram and cue-elicited craving in withdrawn cocaine-dependent patients: A replication. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2001, 27, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Roy, M.; Berman, J.; Gonzalez, B. Blue cone electroretinogram amplitudes are related to dopamine function in cocaine-dependent patients. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 117, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, J.A.; Del Parigi, A.; Merhige, K.; Wolper, C.; Geliebter, A.; Hashim, S.A. Electroretinographic detection of human brain dopamine response to oral food stimulation. Obesity 2013, 21, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, G.J.; Geliebter, A.; Volkow, N.D.; Telang, F.W.; Logan, J.; Jayne, M.C.; Galanti, K.; Selig, P.A.; Han, H.; Zhu, W.; et al. Enhanced striatal dopamine release during food stimulation in binge eating disorder. Obesity 2011, 19, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grand Forks | Philadelphia | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (F/M) | 20 (14/6) | 10 (6/4) | 30 (20/10) |

| Age, years | 24.1 ± 6.8 | 26.1 ± 6.0 | 24.8 ± 6.5 |

| Height, cm | 168.7 ± 9.3 | 172.3 ± 11.1 | 169.9 ± 9.9 |

| Weight, kg | 72.1 ± 10.9 | 70.3 ± 11.1 | 70.7 ± 9.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.3 ± 3.5 | 23.8 ± 4.3 | 24.8 ± 3.8 |

| Chocolate Type | kcal | Cocoa (%) | Sugar (g) | Fat (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lindt® milk | 29 | 38 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Lindt® dark | 30 | 70 | 1.5 | 2.4 |

| Lindt® extra dark | 29 | 85 | 0.6 | 2.3 |

| Lindt® supreme dark | 30 | 90 | 0.4 | 2.8 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casperson, S.L.; Lanza, L.; Albajri, E.; Nasser, J.A. Increasing Chocolate’s Sugar Content Enhances Its Psychoactive Effects and Intake. Nutrients 2019, 11, 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030596

Casperson SL, Lanza L, Albajri E, Nasser JA. Increasing Chocolate’s Sugar Content Enhances Its Psychoactive Effects and Intake. Nutrients. 2019; 11(3):596. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030596

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasperson, Shanon L., Lisa Lanza, Eram Albajri, and Jennifer A. Nasser. 2019. "Increasing Chocolate’s Sugar Content Enhances Its Psychoactive Effects and Intake" Nutrients 11, no. 3: 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030596