The Interplay of Diet Quality and Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Risk Score in Relation to Cognitive Performance Among Urban African Americans

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Participants

2.3. Dietary Methods and Quality

2.3.1. Method

2.3.2. Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HEI2010)

2.3.3. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)

2.3.4. Mean Adequacy Ratio (MAR)

2.3.5. Cognitive Measures

2.3.6. Covariates

2.3.7. Genetic Data

2.3.8. Genetic Risk Score Calculation

2.3.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Cognitive Tests and Their Association with Diet Quality Indices

3.3. hAlzScore Interaction with Diet Quality Scores in Relation to Cognitive Tests

3.4. SNP Interaction with Diet Quality Scores in Relation to Cognitive Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moore, K.; Hughes, C.F.; Ward, M.; Hoey, L.; McNulty, H. Diet, nutrition and the ageing brain: Current evidence and new directions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrott, M.D.; Shatenstein, B.; Ferland, G.; Payette, H.; Morais, J.A.; Belleville, S.; Kergoat, M.J.; Gaudreau, P.; Greenwood, C.E. Relationship between diet quality and cognition depends on socioeconomic position in healthy older adults. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1767–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, R.S.; Waldstein, S.R.; Kuczmarski, M.F.; Pohlig, R.T.; Gerassimakis, C.S.; Gaynor, B.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. Diet quality and cognitive function in an urban sample: Findings from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span (HANDLS) study. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehtisalo, J.; Ngandu, T.; Valve, P.; Antikainen, R.; Laatikainen, T.; Strandberg, T.; Soininen, H.; Tuomilehto, J.; Kivipelto, M.; Lindström, J. Nutrient intake and dietary changes during a 2-year multi-domain lifestyle intervention among older adults: Secondary analysis of the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER) randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodside, J.V.; Gallagher, N.E.; Neville, C.E.; McKinley, M.C. Mediterranean diet interventions to prevent cognitive decline--opportunities and challenges. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 1241–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulose, S.M.; Miller, M.G.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Role of walnuts in maintaining brain health with age. J. Nutr. 2014, 144 (Suppl. 4), 561S–566S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Scott, T.; Gao, X.; Maras, J.E.; Bakun, P.J.; Tucker, K.L. Mediterranean diet, healthy eating index 2005, and cognitive function in middle-aged and older Puerto Rican adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, e271–e273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourida, I.; Soni, M.; Thompson-Coon, J.; Purandare, N.; Lang, I.A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Llewellyn, D.J. Mediterranean diet, cognitive function, and dementia: A systematic review. Epidemiology 2013, 24, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aridi, Y.S.; Walker, J.L.; Wright, O.R.L. The Association between the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and Cognitive Health: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatenstein, B.; Ferland, G.; Belleville, S.; Gray-Donald, K.; Kergoat, M.J.; Morais, J.; Gaudreau, P.; Payette, H.; Greenwood, C. Diet quality and cognition among older adults from the NuAge study. Exp. Gerontol. 2012, 47, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannakoulia, M.; Kontogianni, M.; Scarmeas, N. Cognitive health and Mediterranean diet: Just diet or lifestyle pattern? Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 20, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, I.H.; Miller, J.W. Nutritional factors in physical and cognitive functions of elderly people. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992, 55 (Suppl. 6), 1237S–1243S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troesch, B.; Weber, P.; Mohajeri, M.H. Potential Links between Impaired One-Carbon Metabolism Due to Polymorphisms, Inadequate B-Vitamin Status, and the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2016, 8, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, T.G.; Chouinard-Watkins, R.; Plourde, M. Carriers of an apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele are more vulnerable to a dietary deficiency in omega-3 fatty acids and cognitive decline. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862 Pt A, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.M.; Ha, J.K.; Park, J.M.; Lee, B.D.; Moon, E.; Chung, Y.I.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Mun, C.W.; Kim, T.H.; et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype modulates effects of vitamin B12 and homocysteine on grey matter volume in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychogeriatrics 2016, 16, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.P.; Brickman, A.M. An Inflammation-related Nutrient Pattern is Associated with Both Brain and Cognitive Measures in a Multiethnic Elderly Population. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2018, 15, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jacka, F.N.; Cherbuin, N.; Anstey, K.J.; Sachdev, P.; Butterworth, P. Western diet is associated with a smaller hippocampus: A longitudinal investigation. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, A. An overview of the role of diet during the ageing process. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2008, 13, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, A.; Dehghan, M.; O’Donnell, M.; Anderson, C.; Teo, K.; Gao, P.; Sleight, P.; Dagenais, G.; Probstfield, J.L.; Mente, A.; et al. Healthy eating and reduced risk of cognitive decline: A cohort from 40 countries. Neurology 2015, 84, 2258–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, M.K.; Lepkowski, J.M.; Powe, N.R.; LaVeist, T.; Kuczmarski, M.F.; Zonderman, A.B. Healthy aging in neighborhoods of diversity across the life span (HANDLS): Overcoming barriers to implementing a longitudinal, epidemiologic, urban study of health, race, and socioeconomic status. Ethn. Dis. 2010, 20, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Moshfegh, A.J.; Rhodes, D.G.; Baer, D.J.; Murayi, T.; Clemens, J.C.; Rumpler, W.V.; Paul, D.R.; Sebastian, R.S.; Kuczynski, K.J.; Ingwersen, L.A.; et al. The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raper, N.; Perloff, B.; Ingwersen, L.; Steinfeldt, L.; Anand, J. An overview of USDA’s Dietary Intake Data System. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2004, 17, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FNDDS. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fndds/ (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- How to Choose an Analysis Method Dependent on Purpose. Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/tools.html. (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Healthy Eating Index 2010. Available online: https://handls.nih.gov/06Coll-w01HEI.htm (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Mellen, P.B.; Gao, S.K.; Vitolins, M.Z.; Goff, D.C., Jr. Deteriorating dietary habits among adults with hypertension: DASH dietary accordance, NHANES 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.P.; Foote, J.A.; Wilkens, L.R.; Basiotis, P.P.; Carlson, A.; White, K.K.; Yonemori, K.M. Simple measures of dietary variety are associated with improved dietary quality. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanelli Kuczmarski, M.; Mason, M.A.; Beydoun, M.A.; Allegro, D.; Zonderman, A.B.; Evans, M.K. Dietary patterns and sarcopenia in an urban African American and White population in the United States. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 32, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitamin, C. Fact Sheet. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Fanelli Kuczmarski, M.; Bodt, B.A.; Stave Shupe, E.; Zonderman, A.B.; Evans, M.K. Dietary Patterns Associated with Lower 10-Year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk among Urban African-American and White Adults Consuming Western Diets. Nutrients 2018, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau UC. US Census Bureau, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division; Poverty Thresholds; Bureau UC: Suitland-Silver Hill, MD, USA, 2004. Available online: https://www.census.gov/ces/researchprograms/sehsd_papers_presentations.html (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Bertram, L.; McQueen, M.B.; Mullin, K.; Blacker, D.; Tanzi, R.E. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: The AlzGene database. Nature Genet. 2007, 39, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisato, V.; Zuliani, G.; Vigliano, M.; Longo, G.; Franchini, E.; Secchiero, P.; Zauli, G.; Paraboschi, E.M.; Singh, A.V.; Serino, M.L.; et al. Gene-gene interactions among coding genes of iron-homeostasis proteins and APOE-alleles in cognitive impairment diseases. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finckh, U.; Von Der Kammer, H.; Velden, J.; Michel, T.; Andresen, B.; Deng, A.; Zhang, J.; Müller-Thomsen, T.; Zuchowski, K.; Menzer, G.; et al. Genetic association of a cystatin C gene polymorphism with late-onset Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2000, 57, 1579–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Z. The TT allele of rs405509 synergizes with APOE epsilon4 in the impairment of cognition and its underlying default mode network in non-demented elderly. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berr, C.; Richard, F.; Dufouil, C.; Amant, C.; Alperovitch, A.; Amouyel, P. Polymorphism of the prion protein is associated with cognitive impairment in the elderly: The EVA study. Neurology 1998, 51, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, A.; DeKosky, S.T.; Kamboh, M.I. Lack of association of 5 SNPs in the vicinity of the insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) gene with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 406, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillenes, M.S.; Støen, M.; Günther, C.C.; Selnes, P.; Stenset, V.T.; Espeseth, T.; Reinvang, I.; Fladby, T.; Tønjum, T. Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) rs1937 and AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) rs1130409 alleles are associated with reduced cognitive performance. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 645, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, F.F.; Bertolucci, P.H.; Chen, E.S.; Smith, M.C. Brain-penetrating angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and cognitive change in patients with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014, 42 (Suppl. 3), S321–S324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonell, A.; Balasa, M.; Oliva, R.; Lladó, A.; Bosch, B.; Fabregat, N.; Fortea, J.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Sánchez-Valle, R. A novel PSEN1 gene mutation (L235R) associated with familial early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 496, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SNPedia. Available online: https://www.snpedia.com/index.php/SNPedia 2017 (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Statistics/Data Analysis: Release 15.0 Computer Program; Stata Corporation: College Station, TX, USA, 2017.

- Heckman, J.J. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 1979, 47, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, Y.; Tamhane, A.C. Multiple Comparison Procedures; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Dore, G.A.; Canas, J.A.; Liang, H.; Beydoun, H.A.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. Systemic Inflammation Is Associated with Longitudinal Changes in Cognitive Performance Among Urban Adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersi, M.; Irvine, B.; Gupta, P.; Gomes, J.; Birkett, N.; Krewski, D. Risk factors associated with the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of the evidence. Neurotoxicology 2017, 61, 143–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.R.; Beresford, S.A.; Risica, P.M.; Aragaki, A.; Brunner, R.L.; Bowen, D.J.; Naughton, M.; Rosal, M.C.; Snetselaar, L.; Wenger, N. Low-Fat Dietary Pattern Intervention and Health-Related Quality of Life: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, K.E. Eating well: Ageing gracefully! Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 11 (Suppl. 3), S607–S617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviglus, M.L.; Plassman, B.L.; Pirzada, A.; Bell, C.C.; Bowen, P.E.; Burke, J.R.; Connolly, E.S.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.M.; Granieri, E.C.; McGarry, K.; et al. Risk factors and preventive interventions for Alzheimer disease: State of the science. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritani, T.; Akamatsu, Y. Effect of Exericse and Nutrition upon Lifestyle-Related Disease and Cognitive Function. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2015, 61, S122–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, R.M.; Gianoudis, J.; Prosser, M.; Kidgell, D.; Ellis, K.A.; O’Connell, S.; Nowson, C.A. The effects of a protein enriched diet with lean red meat combined with a multi-modal exercise program on muscle and cognitive health and function in older adults: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015, 16, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsitto, G. Different components of nutritional status in older inpatients with cognitive impairment. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wengreen, H.J.; Neilson, C.; Munger, R.; Corcoran, C. Diet quality is associated with better cognitive test performance among aging men and women. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1944–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flicker, L.; Lautenschlager, N.T.; Almeida, O.P. Healthy mental ageing. J. Br. Menopause Soc. 2006, 12, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardman, R.J.; Kennedy, G.; Macpherson, H.; Scholey, A.B.; Pipingas, A. Adherence to a Mediterranean-Style Diet and Effects on Cognition in Adults: A Qualitative Evaluation and Systematic Review of Longitudinal and Prospective Trials. Front. Nutr. 2016, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dussaillant, C.; Echeverria, G.; Urquiaga, I.; Velasco, N.; Rigotti, A. Current evidence on health benefits of the mediterranean diet. Rev. Med. Chile 2016, 144, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Solfrizzi, V.; Panza, F.; Frisardi, V.; Seripa, D.; Logroscino, G.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Pilotto, A. Diet and Alzheimer’s disease risk factors or prevention: The current evidence. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 677–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, S.D.; Philippou, E. Mediterranean Diet, Cognitive Function, and Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Martin-Calvo, N. Mediterranean diet and life expectancy; beyond olive oil, fruits, and vegetables. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| hAlzScore | rs1049~C | rs1064~A | rs1659~T | rs1799~A | rs2251~T | rs2306~C | rs4055~A | rs4291_A | rs4343_A | rs4496~A | rs4806~C | rs4845~G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hAlzScore | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| rs1049296_C | 0.23 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| rs1064039_A | 0.32 | 0.03 * | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| rs165932_T | 0.32 | 0.03 * | 0.03 * | 1.00 | |||||||||

| rs1799990_A | 0.36 | −0.007 * | 0.02 * | 0.06 * | 1.00 | ||||||||

| rs2251101_T | 0.23 | 0.03 * | 0.004 * | 0.007 * | 0.03 * | 1.00 | |||||||

| rs2306604_C | 0.40 | 0.02 * | 0.05 * | 0.01 * | 0.01 * | 0.05 * | 1.00 | ||||||

| rs405509_A | 0.16 | −0.03 * | −0.03 * | −0.07 * | 0.03 * | −0.07 * | 0.06 * | 1.00 | |||||

| rs4291_A | 0.37 | 0.02 * | −0.05 * | 0.02 * | 0.009 * | 0.01 * | −0.01 * | −0.03 * | 1.00 | ||||

| rs4343_A | 0.31 | −0.001 * | −0.004 * | −0.04 * | −0.02 * | −0.02 * | −0.03 * | 0.02 * | 0.11 | 1.00 | |||

| rs449647_A | 0.17 | −0.01 * | 0.04 * | −0.002 * | −0.03 * | 0.01 * | −0.007 * | −0.43 | 0.03 * | −0.05 * | 1.00 | ||

| rs4806173_C | 0.33 | −0.002 * | −0.004 * | 0.02 * | −0.03 * | −0.03 * | 0.03 * | −0.03 * | −0.004 * | 0.02 * | 0.0230 * | 1.00 | |

| rs4845378_G | 0.21 | 0.03 * | −0.02 * | 0.02 * | 0.01 * | −0.006 * | 0.01 * | 0.02 * | 0.02 * | 0.01 * | −0.01 * | 0.003 * | 1.00 |

| All | Women | Men | Psex1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 304) | (N = 163) | (N = 141) | ||

| Age at baseline, years | 56.90 ± 0.24 | 56.87 ± 0.33 | 56.93 ± 0.35 | 0.90 |

| Education, | 2.29 ± 0.03 | 2.29 ± 0.04 | 2.29 ± 0.05 | 0.96 |

| Literacy (WRAT Score) | 39.9 ± 0.46 | 40.37 ± 0.58 | 39.52 ± 0.73 | 0.36 |

| Poverty Status<125%, % | 44.4 | 46.6 | 41.8 | 0.40 |

| Smoking Status, % | 42.8 * | 33.7 * | 53.2 * | 0.001 * |

| Use of illicit drugs, % | 12.8 * | 8.0 * | 18.4 * | 0.007 * |

| Body Mass Index, kg.m−2 | 30.46 ± 0.43 * | 32.60 ± 0.65 * | 27.99 ± 0.49 * | <0.001 * |

| hAlzScore | 12.63 ± 0.10 | 12.67 ± 0.14 | 12.58 ± 0.16 | 0.70 |

| HEI-total score | 43.98 ± 0.65 * | 45.64 ± 0.94 * | 42.06 ± 0.86 * | 0.006 * |

| DASH-total score | 1.76 ± 0.08 | 2.01 ± 0.12 | 1.47 ± 0.09 | 0.40 |

| MAR-total score | 77.22 ± 1.29 | 76.20 ± 2.16 | 78.39 ± 1.25 | 0.40 |

| Depressive Symptoms (CES-D Score) | 14.67 ± 0.64 | 15.25 ± 0.94 | 14.00 ± 0.64 | 0.33 |

| Diabetes; % | 23.7 | 24.5 | 22.7 | 0.70 |

| Hypertension; % | 62.8 * | 68.1 * | 56.7 * | 0.04 * |

| Dyslipidemia; % | 36.5 * | 41.1 * | 31.2 * | 0.07 * |

| Cardiovascular disease; % | 24.7 | 26.4 | 22.7 | 0.45 |

| Inflammatory conditions; % | 19.4 * | 26.4 * | 11.4 * | 0.001 * |

| NSAIDS; % | 28.6 | 26.4 | 31.2 | 0.35 |

| Cognitive Test Scores | ||||

| MMSE, (N) | 27.04 ± 0.15, (304) | 27.31 ± 0.18, (163) | 26.73 ± 0.24, (141) | 0.05 * |

| CVLT-List A, (N) | 22.27 ± 0.34 *, (260) | 23.40 ± 0.43 *, (147) | 20.80 ± 0.51 *, (113) | <0.001 * |

| CVLT-DFR, (N) | 22.50 ± 0.33 *, (253) | 23.54 ± 0.42 *, (144) | 21.12 ± 0.50 *, (109) | <0.001 * |

| BVRT, (N) | 7.79 ± 0.33, (296) | 7.94 ± 0.46, (159) | 7.61 ± 0.47, (137) | 0.61 |

| Attention, (N) | 5.96 ± 0.14, (271) | 6.00 ± 0.19, (147) | 5.92 ± 0.22, (124) | 0.80 |

| Trails A, (N) | 49.08 ± 3.40, (300) | 45.48 ± 3.75, (161) | 53.25 ± 5.91, (139) | 0.25 |

| Trails B, (N) | 226.14 ± 11.87, (300) | 223.42 ± 16.03, (161) | 229.28 ± 17.71, (139) | 0.80 |

| Digit Span Forward, (N) | 6.74 ± 0.12, (294) | 6.67 ± 0.16, (156) | 6.81 ± 0.18, (138) | 0.58 |

| Digit Span Backward, (N) | 5.08 ± 0.12, (292) | 5.11 ± 0.16, (154) | 5.04 ± 0.17, (138) | 0.76 |

| Clock Command, (N) | 8.64 ± 0.07, (300) | 8.64 ± 0.09, (162) | 8.63 ± 0.10, (138) | 0.94 |

| Identical Pictures, (N) | 20.38 ± 0.34, (230) | 20.72 ± 0.46, (126) | 19.96 ± 0.52, (104) | 0.28 |

| Card Rotation, (N) | 29.03 ± 1.04 *, (233) | 25.89 ± 1.36 *, (128) | 32.84 ± 1.53 *, (105) | <0.001 * |

| Verbal fluency, (N) | 17.34 ± 0.28 *, (301) | 16.78 ± 0.34 *, (160) | 17.97 ± 0.45 *, (141) | 0.03 * |

| All | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE (N) | (p-Values) | β ± SE (N) | (p-Values) | β ± SE (N) | (p-Values) | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam, (MMSE) | ||||||

| hAlzScore | −0.01 ± 0.07 (304) | 0.92 | 0.01 ± 0.09 (163) | 0.93 | 0.03 ± 0.11 (141) | 0.76 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), List A | ||||||

| hAlzScore | −0.34 * ± 0.17 (267) | 0.05 | −0.42 * ± 0.24 (149) | 0.08 | −0.22 ± 0.27 (118) | 0.43 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), Free Recall Long Delay (FRLD) | ||||||

| hAlzScore | −0.44 ** ± 0.17 (261) | 0.01 | −0.48 ** ± 0.24 (146) | 0.04 | −0.39 ± 0.27 (115) | 0.16 |

| Benton Visual Retention Test, (BVRT) | ||||||

| hAlzScore | 0.37 ** ± 0.17 (302) | 0.03 | 0.68 *** ± 0.25 (162) | 0.007 | 0.04 ± 0.25 (140) | 0.88 |

| Clock, Command | ||||||

| hAlzScore | −0.02 ± 0.04 (304) | 0.61 | −0.03 ± 0.05 (164) | 0.53 | 0.01 ± 0.05 (140) | 0.89 |

| Brief Test of Attention | ||||||

| hAlzScore | −0.06 ± 0.07 (277) | 0.43 | −0.16 ± 0.11 (149) | 0.14 | 0.01 ± 0.11 (128) | 0.36 |

| Trailmaking Test, Part A | ||||||

| hAlzScore | −2.861 ± 1.79 (312) | 0.11 | −3.45 ± 2.17 (164) | 0.11 | −4.96 ± 3.07 (148) | 0.11 |

| Trailmaking Test, Part B | ||||||

| hAlzScore | −5.79 ± 5.50 (311) | 0.29 | 0.01 * ± 8.38 (164) | 0.10 | −12.52 * ± 7.66 (147) | 0.10 |

| Digits Span, Forward | ||||||

| hAlzScore | 0.02 ± 0.06 (300) | 0.77 | −0.17 ± 0.09 (158) | 0.84 | 0.10 ± 0.09 (142) | 0.28 |

| Digits Span, Backward | ||||||

| hAlzScore | −0.04 ± 0.05 (298) | 0.51 | −0.14 * ± 0.08 (156) | 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.08 (142) | 0.32 |

| Card Rotation test | ||||||

| hAlzScore | 0.08 ± 0.56 (236) | 0.89 | 0.40 ± 0.81 (129) | 0.62 | −0.94 ± 0.82 (107) | 0.25 |

| Identical Pictures | ||||||

| hAlzScore | 0.20 ± 0.18 (233) | 0.28 | 0.23 ± 0.27 (127) | 0.38 | 0.12 ± 0.28 (106) | 0.66 |

| Animal Fluency | ||||||

| hAlzScore | 0.05 ± 0.16 (307) | 0.71 | −0.12 ± 0.19 (162) | 0.53 | 0.26 ± 0.24 (145) | 0.28 |

| All | Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mini-Mental State Exam, MMSE | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.01 ± 0.01, 0.60 | 0.002 ± 0.01, 0.86 | −0.02 ± 0.02, 0.45 |

| Model 2: DASH | 0.02 ± 0.09, 0.80 | −0.05 ± 0.10, 0.64 | 0.20 ± 0.18, 0.28 |

| Model 3: MAR | 0.002 ± 0.01, 0.77 | 0.004 ± 0.01, 0.60 | −0.01 ± 0.02, 0.73 |

| California Verbal Learning Test CVLT, List A | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.034 ± 0.03, 0.23 | −0.01 ± 0.04, 0.89 | −0.08 ± 0.05, 0.12 |

| Model 2: DASH | −0.20 ± 0.24, 0.40 | −0.14 ± 0.29, 0.63 | −0.37 ± 0.44, 0.41 |

| Model 3: MAR | −0.03 ± 0.02, 0.08 | −0.02 ± 0.02, 0.34 | −0.09 ± 0.04, 0.03 |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), Free Recall Long Delay (FRLD) | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.03 ± 0.03, 0.28 | 0.00 ± 0.04, 0.99 | −0.07 ± 0.05. 0.16 |

| Model 2: DASH | −0.25 ± 0.24, 0.28 | −0.14 ± 0.29, 0.63 | −0.57 ± 0.44, 0.20 |

| Model 3: MAR | −0.03 ± 0.02, 0.09 | −0.02 ± 0.02, 0.44 | −0.08 ± 0.04, 0.05 |

| Benton Visual Retention Test, BVRT | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | 0.01 ± 0.03, 0.80 | 0.001 ± 0.04, 0.98 | 0.04 ± 0.05, 0.37 |

| Model 2: DASH | −0.20 ± 0.25, 0.41 | −0.28 ± 0.31, 0.36 | 0.16 ± 0.42, 0.71 |

| Model 3: MAR | −0.04 ± 0.02, 0.03 | −0.04 ± 0.02, 0.07 | −0.02 ± 0.04, 0.68 |

| Clock, Command | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.001 ± 0.01, 0.90 | −0.01 ± 0.01, 0.26 | 0.01 ± 0.01, 0.23 |

| Model 2: DASH | −0.05 ± 0.05, 0.31 | −0.08 ± 0.07, 0.22 | −0.01 ± 0.01, 0.91 |

| Model 3: MAR | 0.01 ± 0.004, 0.17 | 0.002 ± 0.004, 0.66 | 0.013 ± 0.01, 0.14 |

| Brief Test of Attention | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.01 ± 0.01, 0.35 | −0.01 ± 0.02, 0.39 | −0.004 ± 0.02, 0.84 |

| Model 2: DASH | −0.07 ± 0.10, 0.49 | −0.08 ± 0.13, 0.53 | −0.10 ± 0.18, 0.61 |

| Model 3: MAR | 0.02 ± 0.01, 0.03 | 0.01 ± 0.01, 0.11 | 0.03 ± 0.02, 0.09 |

| Trailmaking Test, Part A | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | 0.01 ± 0.31, 0.97 | 0.01 ± 0.34, 0.98 | −0.09 ± 0.60, 0.88 |

| Model 2: DASH | −3.41 ± 2.55, 0.18 | −1.71 ± 2.61, 0.51 | −7.75 ± 5.37, 0.15 |

| Model 3: MAR | −0.04 ± 0.18, 0.84 | −0.01 ± 0.17, 0.96 | 0.07 ± 0.51, 0.90 |

| Trailmaking Test, Part B | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | 0.02 ± 0.96, 0.98 | −0.69 ± 1.31, 0.60 | 1.28 ± 1.49, 0.98 |

| Model 2: DASH | 7.95 ± 7.80, 0.31 | 15.34 ± 9.90, 0.12 | −8.68 ± 13.48, 0.52 |

| Model 3: MAR | 0.09 ± 0.541, 0.87 | −0.25 ± 0.65, 0.70 | 1.15 ± 1.26, 0.37 |

| Digits Span, Forward | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | 0.02 ± 0.01, 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.01, 0.17 | 0.02 ± 0.02, 0.29 |

| Model 2: DASH | −0.07 ± 0.08, 0.40 | 0.02 ± 0.10, 0.85 | −0.24 ± 0.16, 0.13 |

| Model 3: MAR | 0.01 ± 0.01, 0.33 | 0.01 ± 0.01, 0.29 | 0.002 ± 0.02, 0.88 |

| Digits Span, Backward | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.01 ± 0.01, 0.21 | −0.01 ± 0.01, 0.40 | −0.01 ± 0.02, 0.60 |

| Model 2: DASH | −0.07 ± 0.08, 0.34 | −0.15 ± 0.10, 0.11 | 0.07 ± 0.14, 0.62 |

| Model 3: MAR | 0.003 ± 0.01, 0.54 | 0.01 ± 0.01, 0.31 | 0.001 ± 0.01, 0.97 |

| Card Rotation test | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.02 ± 0.09, 0.81 | −0.04 ± 0.12, 0.74 | 0.05 ± 0.16, 0.75 |

| Model 2: DASH | 0.26 ± 0.76, 0.74 | −0.08 ± 0.94, 0.93 | 1.07 ± 1.32, 0.42 |

| Model 3: MAR | 0.05 ± 0.05, 0.31 | 0.03 ± 0.06, 0.65 | 0.21 ± 0.15, 0.16 |

| Identical Pictures | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.01 ± 0.03, 0.69 | -0.03 ± 0.04, 0.51 | 0.03 ± 0.06, 0.65 |

| Model 2: DASH | 0.07 ± 0.25, 0.77 | 0.08 ± 0.31, 0.81 | 0.04 ± 0.45, 0.93 |

| Model 3: MAR | −0.01 ± 0.02, 0.56 | -0.02 ± 0.02, 0.30 | 0.09 ± 0.05, 0.08 |

| Verbal fluency | |||

| Model 1: HEI-2010 | −0.002 ± 0.03, 0.93 | -0.01 ± 0.03, 0.72 | 0.001 ± 0.05, 0.99 |

| Model 2: DASH | −0.11 ± 0.21, 0.61 | -0.18 ± 0.23, 0.44 | 0.03 ± 0.42, 0.95 |

| Model 3: MAR | 0.01 ± 0.01, 0.41 | 0.01 ± 0.02, 0.55 | 0.02 ± 0.04, 0.58 |

| All | Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clock, Command | |||

| Model 1: hAlzScore × HEI2010 | 0.01 ± 0.003, 0.10 | 0.01 ± 0.004, 0.17 | 0.003 ± 0.01, 0.46 |

| Model 2: hAlzScore × DASH | 0.02 ± 0.03, 0.49 | 0.02 ± 0.03, 0.57 | 0.01 ± 0.05, 0.88 |

| Model 3: hAlzScore × MAR | 0.003 ± 0.001, 0.13 | 0.01 ± 0.002, 0.04 ** | −0.003 ± 0.0003, 0.38 |

| Card Rotation test | |||

| Model 1: hAlzScore × HEI2010 | 0.11 ± 0.05, 0.04 ** | 0.10 ± 0.07, 0.13 | 0.08 ± 0.10, 0.44 |

| Model 2: hAlzScore × DASH | 0.45 ± 0.44, 0.31 | 0.73 ± 0.54, 0.18 | −0.59 ± 0.83, 0.47 |

| Model 3: hAlzScore × MAR | −0.02 ± 0.03, 0.56 | −0.02 ± 0.04, 0.63 | 0.03 ± 0.07, 0.66 |

| Identical Pictures | |||

| Model 1: hAlzScore × HEI2010 | 0.03 ± 0.02, 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.02, 0.31 | 0.05 ± 0.03, 0.13 |

| Model 2: hAlzScore × DASH | 0.14 ± 0.15, 0.35 | 0.25 ± 0.18, 0.16 | −0.10 ± 0.28, 0.71 |

| Model 3: hAlzScore × MAR | 0.004 ± 0.01, 0.74 | 0.002 ± 0.01, 0.85 | 0.02 ± 0.02, 0.39 |

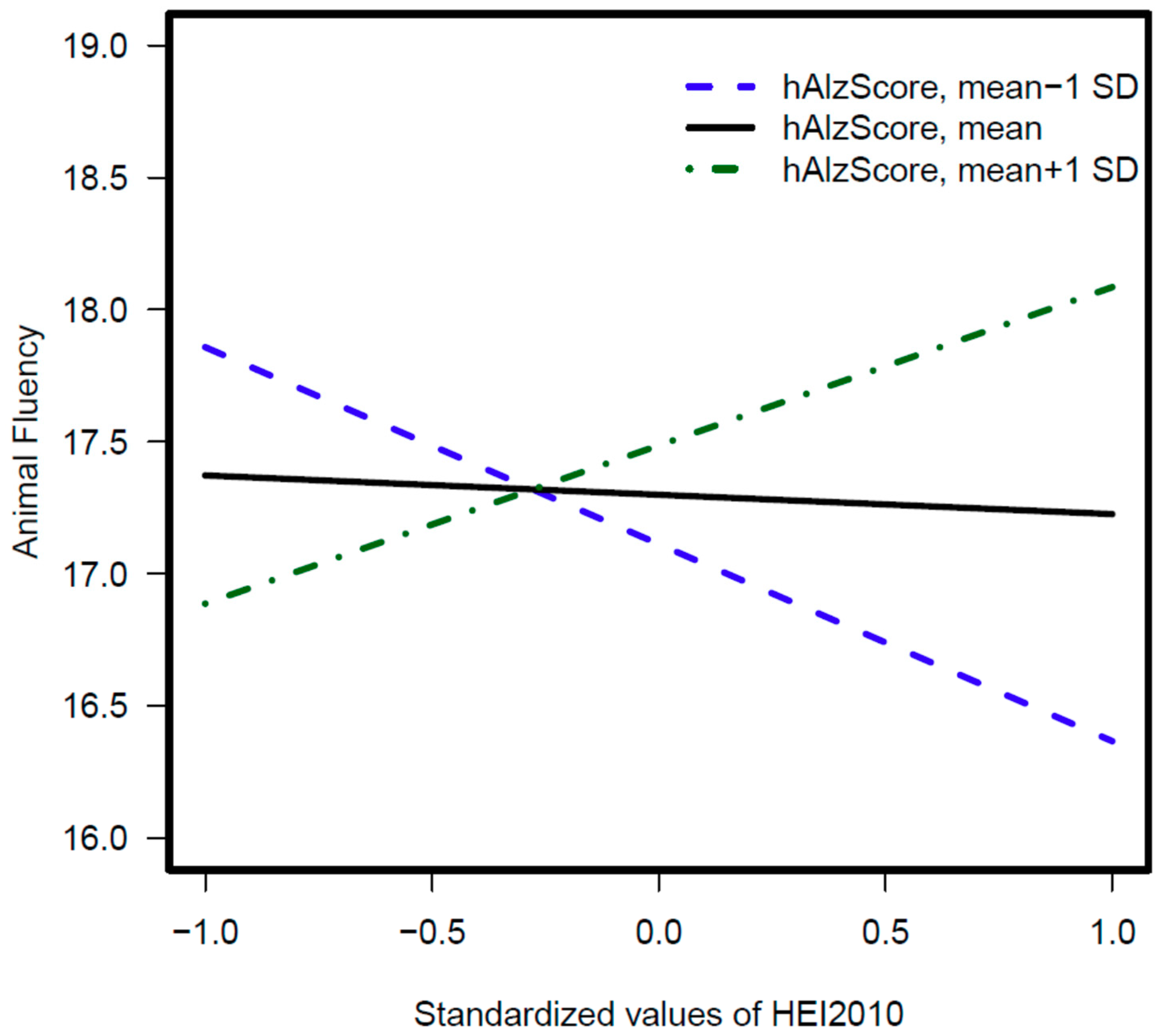

| Verbal fluency | |||

| Model 1: hAlzScore × HEI2010 | 0.03 ± 0.01, 0.02 ** | 0.04 ± 0.02, 0.02 ** | 0.02 ± 0.02, 0.37 |

| Model 2: hAlzScore × DASH | 0.18 ± 0.11, 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.12, 0.04 ** | −0.01 ± 0.22, 0.98 |

| Model 3: hAlzScore × MAR | 0.01 ± 0.01, 0.32 | 0.01 ± 0.01, 0.51 | 0.01 ± 0.02, 0.71 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hossain, S.; Beydoun, M.A.; Kuczmarski, M.F.; Tajuddin, S.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. The Interplay of Diet Quality and Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Risk Score in Relation to Cognitive Performance Among Urban African Americans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2181. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092181

Hossain S, Beydoun MA, Kuczmarski MF, Tajuddin S, Evans MK, Zonderman AB. The Interplay of Diet Quality and Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Risk Score in Relation to Cognitive Performance Among Urban African Americans. Nutrients. 2019; 11(9):2181. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092181

Chicago/Turabian StyleHossain, Sharmin, May A. Beydoun, Marie F Kuczmarski, Salman Tajuddin, Michele K Evans, and Alan B Zonderman. 2019. "The Interplay of Diet Quality and Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Risk Score in Relation to Cognitive Performance Among Urban African Americans" Nutrients 11, no. 9: 2181. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092181