Examining the Influence of Cultural Immersion on Willingness to Try Fruits and Vegetables among Children in Guam: The Traditions Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

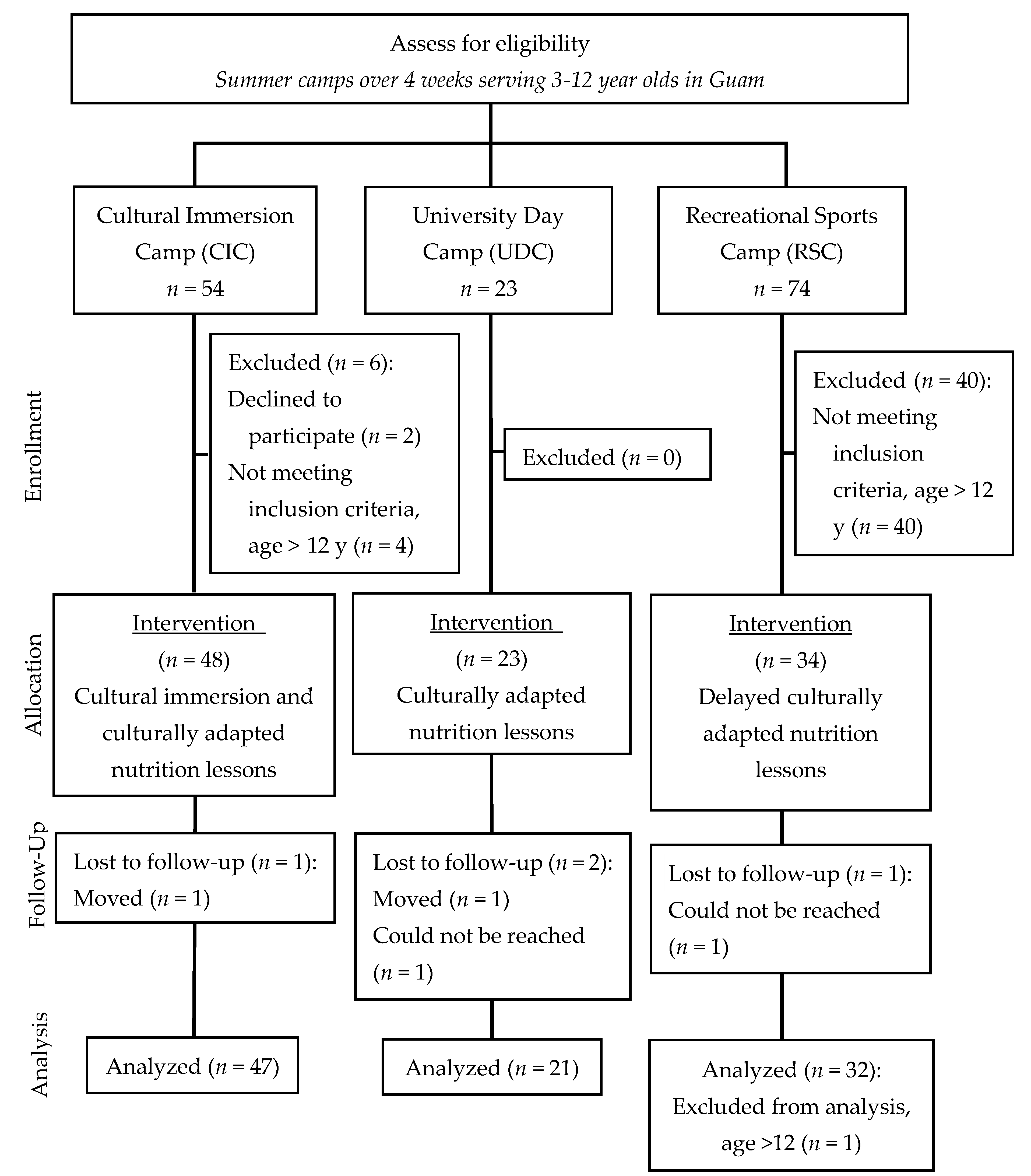

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance; The National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.T.; Drewnowski, A.; Kumanyika, S.K.; Glass, T.A. A systems-oriented multi-level framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2009, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Govula, C.; Kattelman, K.; Ren, C. Culturally appropriate nutrition lessons increased fruit and vegetable consumption in American Indian children. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 22, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, L.; Brug, J. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among 6–12 year-old children and effective interventions to increase consumption. J. Hum. Nutr. Dietet. 2005, 18, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranowski, T.; Baranowski, J.C.; Cullen, K.W.; Thompson, D.I.; Nicklas, T.; Zakeri, I.E.; Rochson, J. The fun, food, and fitness project (FFFP): The Baylor GEMS pilot study. Ethn. Dis. 2003, 13, S30–S39. [Google Scholar]

- Pobocik, R.S.; Montgomery, D. Roff Gemlo, L. Modification of a school-based nutrition education curriculum to be culturally relevant for western pacific islanders. J. Nutr. Educ. 1998, 30, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.K.; Worobey, J. Early influences on the development of food preferences. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aflague, T.F.; Leon Guerrero, R.T.; Boushey, C.J. Adaptation and evaluation of the WillTry tool to assess willingness to try fruits and vegetables among children 3–11y in Guam. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomson, J.L.; McCabe-Sellers, B.J.; Strickland, E.; Lovera, D.; Nuss, H.J.; Yadrick, K.; Duke, S.; Bogle, M.L. Development and evaluation of WillTry. An instrument for measuring children’s willingness to try fruits and vegetables. Appetite 2010, 54, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowdon, W.; Raj, A.; Reeve, E.; Guerrero, R.L.T.; Fesaitu, J.; Catine, K.; Guignet, C. Processed Foods Available in the Pacific Islands; Global Health: Edinburgh, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B.M. Contemporary nutritional transition: Determinants of diet and its impact on body composition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2011, 70, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuhnlein, H.V.; Receveur, O. Dietary change and traditional food systems of indigenous peoples. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1996, 16, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satia-About a, J.; Patterson, E.R.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Elder, J. Dietary acculturation applications to nutrition research and dietetics. JADA 2002, 102, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Torsch, V. Living the health transition among the Chamorros of Guam. Pac. Health Dialog 2002, 9, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuhnlein, H.; Erasmus, B.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.; Englberger, L.; Okeke, C.; Turner, N.; Allen, L.; Bhattacharjee, L. Indigenous peoples’ food systems for health: Finding interventions that work. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 9, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renzaho, A.M.N.; Swinburn, B.; Burns, C. Maintenance of traditional cultural orientation is associated with lower rates of obesity and sedentary behaviours among African migrant children to Australia. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lind, C.; Mirchandani, G.G.; Castrucci, B.C.; Chavez, N.; Handler, A.; Hoelscher, D.M. The effects of acculturation on healthy lifestyle characteristics among Hispanic fourth-grade children in Texas public schools, 2004–2005. J. Sch. Health 2012, 82, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, A.D.; McGregor, J.C.; Perencevich, E.N.; Furuno, J.P.; Zhu, J.; Peterson, D.E.; Finkelstein, J. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2006, 13, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokua Hawai’i Foundation Resources: AINA Nutrition Education Unit Overview. Kokua Hawaii Foundation: Haleiwa, HI, USA. Available online: http://kokuahawaiifoundation.org/aina/resources (accessed on 8 March 2014).

- Auld, G.; Baker, S.; Conway, L.; Dollahite, J.; Lambea, M.C.; McGirr, K. Outcome effectiveness of the widely adopted EFNEP curriculum Eating Smart Being Active. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, B.L.; Schap, T.E.; Ettienne-Gittens, R.; Zhu, F.M.; Bosch, M.; Delp, E.J.; Ebert, D.S.; Kerr, D.A.; Boushey, C.J. Novel technologies for assessing dietary intake: Evaluating the usability of a mobile telephone food record among adults and adolescents. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, B.L.; Schap, T.E.; Zhu, F.M.; Mariappan, A.; Bosch, M.; Delp, E.J.; Ebert, D.S.; Kerr, D.A.; Boushey, C.J. Evidence-based development of a mobile telephone food record. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aflague, T.F.; Boushey, C.J.; Leon-Guerrero, R.T.; Ahmad, Z.; Kerr, D.A.; Delp, E.J. Feasibility and use of the mobile food record for capturing eating occasions among children ages 3–10 years in Guam. Nutrients. 2015, 7, 4403–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaholokula, J.K.; Iwane, M.K.; Nacapoy, A.H. Effects of received racism and acculturation on hypertension in Native Hawaiians. Hawaii Med. J. 2010, 69, 11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedman, L.M.; Furberg, C.D.; DeMets, D.L. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials; John Wright, PSG Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Chiuve, S.E.; Fung, T.T.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; McCullough, M.L.; Wang, M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hochberg, Y.; Tamhane, A.C. Multiple Comparison Procedures; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fialkowski, M.K.; DeBaryshe, B.; Bersamin, A.; Nigg, C.; Leon Guerrero, R.; Rojas, G.; Areta, A.A.R.; Vargo, A.; Belyeu-Camacho, T.; Castro, R.; et al. A community engagement process identifies environmental priorities to prevent early childhood obesity: The children’s healthy living (CHL) program for remote underserved populations in the US affiliated Pacific Islands, Hawaii and Alaska. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 18, 2261–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Summer Day Camp Programs | Cultural Immersion Camp (CIC) | University Day Camp (UDC) | Recreational Sports Camp (RSC) |

| Philosophy/Mission | To promote and perpetuate the Chamorro language and culture through the implementation of immersion | Food, Fitness, & Fun: To promote physical activity and healthy foods for children and families with limited resources based on the OrganWise Guys® curricula. | To promote health, recreation, physical activity, and a lifetime of wellness in an environment with fun, cooperation, sportsmanship, and environmental awareness. |

| Language | Chamorro, spoken 80% of time | English | English |

| Core Subject Areas | Language (speaking, reading, & writing) Culture/Traditions/ValuesHistory (4 eras) | Ties healthy eating to human anatomy and physiology. Links core curricula standards: Math, language arts, and science | Daily physical activity, age-appropriate skill development in various sports, and recreational games. |

| Activities | Food:

| Food:

| Physical Activity:

|

| Lesson 1 | Lesson 2 | Lesson 3 | Lesson 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Safety & Hand Washing | A Foundation for Good Health | Label Detectives | Food Choices for Your Environment |

Key Concepts:

| Key Concepts

| Key Concepts

| Key Concepts

|

Activities:

| Activities:

| Activities:

| Activities:

|

| Recipe: Breadfruit kabobs: steamed breadfruit dipped in warm coconut milk | Recipe: Eggplant (egg) scramble | Recipe: Papaya and/or mango smoothie | Recipe: Soursop popsicles and frozen or dehydrated star fruit |

| Child Characteristics | n | CIC 1 (n = 46) | UDC 2 (n = 21) | RSC 3 (n = 32) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | n (percent, %) | |||

| Boys | 29 | 17 (37) | 1 (5) | 11 (34) |

| Girls | 70 | 29 (63) | 20 (95) | 21 (66) |

| Ethnic Group | ||||

| Chamorro, only | 53 | 25 (54) | 12 (57) | 16 (50) |

| Chamorro, mixed | 33 | 21(46) | 3 (14) | 9 (28) |

| Other | 12 | 0 (0) | 6 (29) | 6 (19) |

| No response | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Age Group, years | ||||

| 3–6 | 28 | 17 (37) | 1 (5) | 10 (31) |

| 7–8 | 39 | 14 (30) | 8 (38) | 17 (53) |

| 9– 12 | 32 | 15 (33) | 12 (57) | 5 (16) |

| Weight status, BMI † percentile | ||||

| Underweight, <5th percentile | 3 | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Healthy weight, 5 to <85th percentile | 66 | 28 (61) | 16 (76) | 22 (69) |

| Overweight, ≥85 to <95th percentile | 16 | 9 (20) | 3 (14) | 4 (12) |

| Obese, ≥95th percentile | 14 | 7 (15) | 1 (5) | 6 (19) |

| Parent’s cultural affiliation | ||||

| Traditional | 15 | 6 (13) | 5 (23) | 4 (12) |

| Integrated | 79 | 38 (83) | 14 (67) | 27 (84) |

| Marginalized | 2 | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Assimilated | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| No response | 2 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Pre-Assessments | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Adapted WillTry (unadjusted) scores | ||||

| Local Novel | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | |

| Local Common | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | |

| Imported | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | |

| Whole FV ‡ (servings) | 0.6 ± 0.5 a | 1.2 ± 1.1 b | n/a # | |

| Post Means 1 | p-Value for Pairwise Comparisons 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIC (n = 47) | UDC (n = 21) | RSC (n = 32) | Global p-value 2 | CIC vs. UDC | CIC vs. RSC | USC vs. RSC | |

| Local Novel Adapted WillTry score | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.87 |

| Local Common Adapted WillTry Score | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| Imported Adapted WillTry Score | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.27 | 0.06 |

| Whole FV (servings) | 0.3 a | 0.7 b | n/a ‡ | 0.25 | 0.25 | n/a | n/a |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aflague, T.F.; Leon Guerrero, R.T.; Delormier, T.; Novotny, R.; Wilkens, L.R.; Boushey, C.J. Examining the Influence of Cultural Immersion on Willingness to Try Fruits and Vegetables among Children in Guam: The Traditions Pilot Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010018

Aflague TF, Leon Guerrero RT, Delormier T, Novotny R, Wilkens LR, Boushey CJ. Examining the Influence of Cultural Immersion on Willingness to Try Fruits and Vegetables among Children in Guam: The Traditions Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2020; 12(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleAflague, Tanisha F., Rachael T. Leon Guerrero, Treena Delormier, Rachel Novotny, Lynne R. Wilkens, and Carol J. Boushey. 2020. "Examining the Influence of Cultural Immersion on Willingness to Try Fruits and Vegetables among Children in Guam: The Traditions Pilot Study" Nutrients 12, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010018

APA StyleAflague, T. F., Leon Guerrero, R. T., Delormier, T., Novotny, R., Wilkens, L. R., & Boushey, C. J. (2020). Examining the Influence of Cultural Immersion on Willingness to Try Fruits and Vegetables among Children in Guam: The Traditions Pilot Study. Nutrients, 12(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010018