Vitamin C and the Lens: New Insights into Delaying the Onset of Cataract

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Cataract Epidemic

3. Aetiology of the Different Types of Cataract

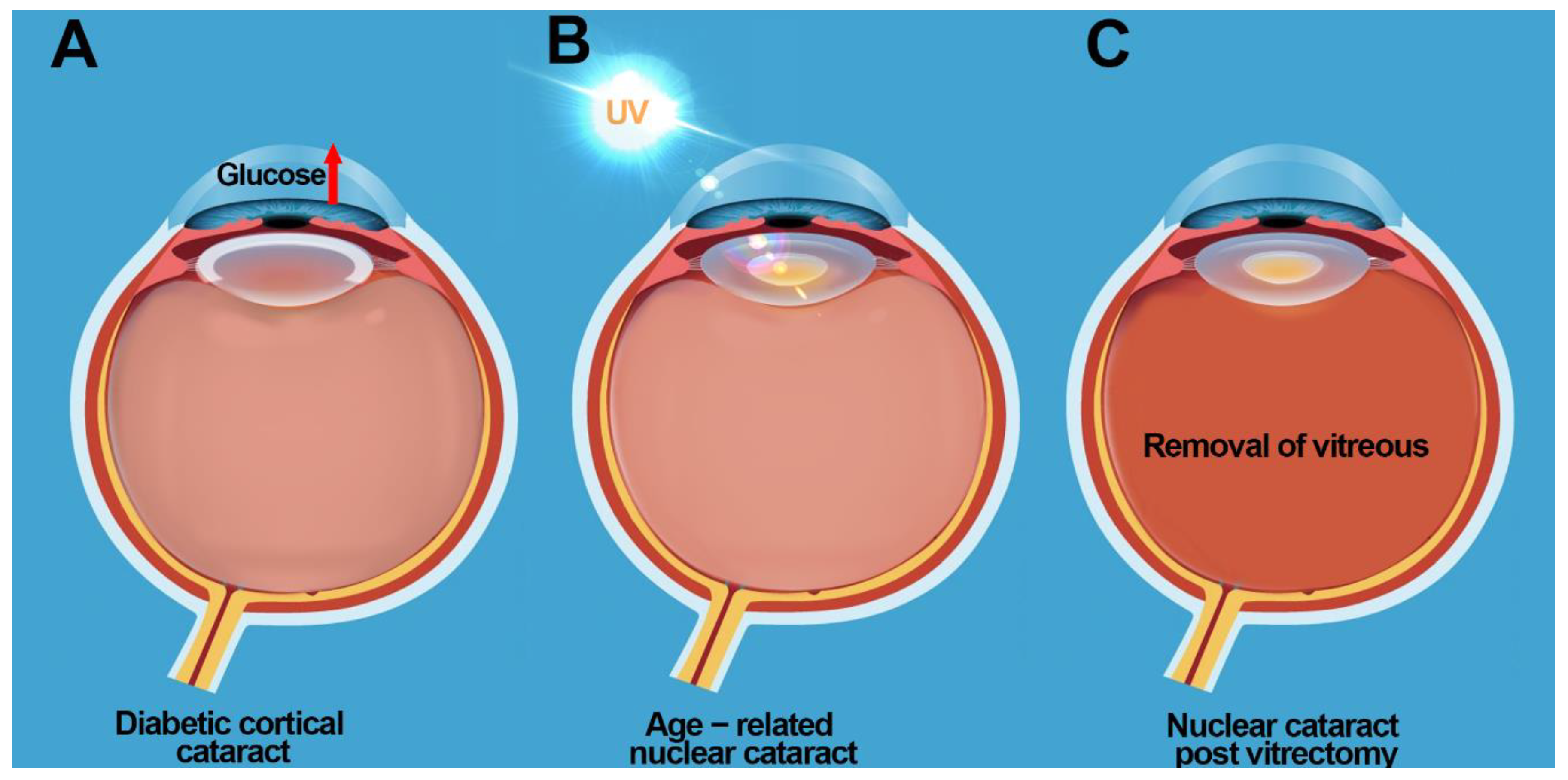

3.1. Diabetic Cortical Cataracts

3.2. Nuclear Cataracts

4. Roles of Vitamin C in the Eye

5. Biochemical Properties of Vitamin C

6. Transport of Vitamin C into the Ocular Humors

7. Delivery and Uptake of Vitamin C and DHA into the Lens

8. Evidence of the Effects of Vitamin C on Cataract Prevention

8.1. Animal Studies

8.1.1. The Antioxidant Role of Vitamin C in the Lens

8.1.2. The Pro-Oxidant Role of Vitamin C in the Lens

8.2. Evidence of the Effects of Supplemental or Dietary Vitamin C on the Prevention of Cataracts in Humans

9. Cataract Prevention Post Vitrectomy: Restoring Antioxidant Balance in the Eye?

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. Blindness and Vision Impairment Prevention. Available online: https://www.who.int/blindness/causes/priority/en/index1.html (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Hodge, W.G.; Whitcher, J.P.; Satariano, W. Risk factors for age-related cataracts. Epidemiol. Rev. 1995, 17, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Age Related Eye Disease Group. Risk factors associated with age-related nuclear and cortical cataract: A case-control study in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, AREDS Report No. 5. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.E.; Klein, R.; Wang, Q.; Moss, S.E. Older-onset diabetes and lens opacities: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalm. Epid. 1995, 2, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian, G.; Taylor, H. Cataract blindness-challenges for the 21st century. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weikel, K.A.; Garber, C.; Baburins, A.; Taylor, A. Nutritional modulation of cataract. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braakhuis, A.J.; Donaldson, C.I.; Lim, J.C.; Donaldson, P.J. Nutritional strategies to prevent lens cataract: Current status and future strategies. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sella, R.; Afshari, N.A. Nutritional effect on age-related cataract formation and progression. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 30, 643–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, Y.B.; Holekamp, N.M.; Kramer, B.C.; Crowley, J.R.; Wilkins, M.A.; Chu, F.; Malone, P.E.; Mangers, S.J.; Hou, J.H.; Siegfried, C.J.; et al. The gel state of the vitreous and ascorbate-dependent oxygen consumption: Relationship to the etiology of nuclear cataracts. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2009, 127, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumari, S.; Talwar, B.; Dharmalingam, K.; Ravindran, R.D.; Jayanthi, R.; Sundaresan, P.; Saravanan, C.; Young, I.S.; Dangour, A.D.; Fletcher, A.E. Polymorphisms in sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter genes and plasma, aqueous humor and lens nucleus ascorbate concentrations in an ascorbate depleted setting. Exp. Eye Res. 2014, 124, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, F.; Moreaux, V.; Birlouez-Aragon, I.; Junes, P.; Mondon, H. Decrease in vitamin C concentration in human lenses during cataract progression. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1998, 68, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.; Jacques, P.F.; Nadler, D.; Morrow, F.; Sulsky, S.I.; Shepard, D. Relationship in humans between ascorbic acid consumption and levels of total and reduced ascorbic acid in lens, aqueous humor, and plasma. Curr. Eye Res. 1991, 10, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Siegfried, C.; Kubota, M.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Dana, B.; Huang, A.; Beebe, D.; Yan, H.; et al. Expression Profiling of Ascorbic Acid–Related Transporters in Human and Mouse Eyes. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 3440–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, P.J.; Grey, A.C.; Maceo Heilman, B.; Lim, J.C.; Vaghefi, E. The physiological optics of the lens. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 56, e1–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsuan, J.D.; Brown, N.A.; Bron, A.J.; Patel, C.K.; Rosen, P.H. Posterior subcapsular and nuclear cataract after vitrectomy. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2001, 27, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Kahloun, R.; Bourne, R.; Limburg, H.; Flaxman, S.R.; Jonas, J.B.; Keefe, J.; Leasher, J.; Naidoo, K.; Pesudovs, K.; et al. Number of people blind or visually impaired by cataract worldwide and in world regions, 1990 to 2010. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 6762–6769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascolini, D.; Mariotti, S.P. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 96, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.R. Cataract: How much surgery do we have to do? Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.K.; Valmadrid, C.T. Epidemiology of risk factors for age-related cataract. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1995, 39, 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, J.J.; van Heyningen, R. Epidemiology and risk factors for cataract. Eye 1987, 1, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, N.M.; Shui, Y.B.; Beebe, D.C. Vitrectomy surgery increases oxygen exposure to the lens: A possible mechanism for nuclear cataract formation. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 139, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, A.J.; Sparrow, J.; Brown, N.A.; Harding, J.J.; Blakytny, R. The lens in diabetets. Eye 1993, 7, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uspal, N.G.; Schapiro, E.S. Cataracts as the initial manifestation of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2011, 27, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chylack, L.T.J.; Ransil, B.J.; White, O. Classification of human senile cataractous change by the American Cooperative Cataract Research Group (CCRG) method: III. The association of nuclear color (sclerosis) with extent of cataract formation, age, and visual acuity. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1984, 25, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Adrien Shun-Shin, G.; Brown, N.P.; Bron, A.J.; Sparrow, J.M. Dynamic nature of posterior subcapsular cataract. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1989, 73, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.; Shah, D.N.; Chaudhary, R.P. Scleritis and Takayasu’s disease—Rare combined presentation. Nepal. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 9, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.E.; Klein, R.E.; Moss, S.E. Incidence of cataract surgery in the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1995, 119, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caird, F.I.; Garrett, C.J. Progression and regression of diabetic retinopathy. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1962, 55, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, J.H. Mechanisms initiating cataract formation. Proctor Lecture. Investig. Ophthalmol. 1974, 13, 713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, J.H. Cataracts in galactosemia. The Jonas S. Friedenwald Memorial Lecture. Investig. Ophthalmol. 1965, 4, 786–799. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.S.; Ho, E.C.; Lam, K.S.; Chung, S.K. Contribution of polyol pathway to diabetes-induced oxidative stress. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, S233–S236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.W.; Ho, Y.S.; Chung, S.K.; Chung, S.S. Synergistic effect of osmotic and oxidative stress in slow-developing cataract formation. Exp. Eye Res. 2008, 87, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammarata, P.R.; Schafer, G.; Chen, S.W.; Guo, Z.; Reeves, R.E. Osmoregulatory alterations in taurine uptake by cultured human and bovine lens epithelial cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 425–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jedziniak, J.A.; Chylack, L.T., Jr.; Cheng, H.M.; Gillis, M.K.; Kalustian, A.A.; Tung, W.H. The sorbitol pathway in the human lens: Aldose reductase and polyol dehydrogenase. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1981, 20, 314–326. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, S.D.; Kinoshita, J.H. The absence of cataracts in mice with congenital hyperglycemia. Exp. Eye Res. 1974, 19, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.C.; Vorontsova, I.; Martis, R.M.; Donaldson, P.J. Animal Models in Cataract Research. In Animal Models for the Study of Human Disease, 2nd ed.; Conn, P.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R.; Lin, B.; Lee, K.W.; Ortwerth, B.J. Similarity of the yellow chromophores isolated from human cataracts with those from ascorbic acid-modified calf lens proteins: Evidence for ascorbic acid glycation during cataract formation. Biochim. Biphys. Acta 2001, 1537, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truscott, R.J.; Augusteyn, R.C. Changes in human lens proteins during nuclear cataract formation. Exp. Eye Res. 1977, 24, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truscott, R.J.; Augusteyn, R.C. The state of sulphydryl groups in normal and cataractous human lenses. Exp. Eye Res. 1977, 25, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, A.; Roy, D. Disulfide-linked high molecular weight protein associated with human cataract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 3244–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, M.F. Redox regulation in the lens. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2003, 22, 657–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truscott, R.J. Age-related nuclear cataract-oxidation is the key. Exp. Eye Res. 2005, 80, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, C.J.; Shui, Y.B. Intraocular Oxygen and Antioxidant Status: New Insights on the Effect of Vitrectomy and Glaucoma Pathogenesis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 203, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.; Jacques, P.F.; Nowell, T.; Perrone, G.; Blumberg, J.; Handelman, G.; Jozwiak, B.; Nadler, D. Vitamin C in human and guinea pig aqueous, lens and plasma in relation to intake. Curr. Eye Res. 1997, 16, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.N. Glutathione and its function in the lens. Exp. Eye Res. 1990, 50, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.H.; Truscott, R.J. An impediment to glutathione diffusion in older normal human lenses: A possible precondition for nuclear cataract. Exp. Eye Res. 1998, 67, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherfan, G.M.; Michels, R.G.; de Bustros, S.; Enger, C.; Glaser, B.M. Nuclear sclerotic cataract after vitrectomy for idiopathic epiretinal membranes causing macular pucker. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1991, 111, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Effenterre, G.; Ameline, B.; Campinchi, F.; Quesnot, S.; Le Mer, Y.J.H. Is vitrectomy cataractogenic? Study of changes of the crystalline lens after surgery of retinal detachment. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 1992, 15, 449–454. [Google Scholar]

- Melberg, N.S.; Thomas, M.A. Nuclear sclerotic cataract after vitrectomy in patients younger than 50 years of age. Ophthalmology 1995, 102, 1466–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheng, L.; Azen, S.P.; El-Brady, M.H.; Scholz, B.M.; Chaidhawangul, S.; Toyoguchi, M.; Freeman, W.R. Duration of vitrectomy and postoperative cataract in the Vitrectomy for Macular Hole Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 132, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.T.; Glaser, B.M.; Sjaarda, R.N.; Murphy, R.P. Progression of nuclear sclerosis in long-term visual results after vitrectomy with transforming growth factor Beta-2 for macular holes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1995, 119, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbazetto, I.A.; Liang, J.; Chang, S.; Zheng, L.; Spector, R.A.; Dillon, J.P. Oxygen tension in the rabbit lens and vitreous before and after vitrectomy. Exp. Eye Res. 2004, 78, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNulty, R.; Wang, H.; Mathias, R.T.; Ortwerth, B.J.; Truscott, R.J.; Bassnett, S. Regulation of tissue oxygen levels in the mammalian lens. J. Physiol. 2004, 559, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, Y.B.; Fu, J.J.; Garcia, C.; Dattilo, L.K.; Rajagopal, R.; McMillan, S.; Mak, G.; Holekamp, N.M.; Lewis, A. Oxygen distribution in the rabbit eye and oxygen consumption by the lens. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, D.C.; Shui, Y.B.; Siegfried, C.J.; Holekamp, N.M.; Bai, F. Preserve the (intraocular) environment: The importance of maintaining normal oxygen gradients in the eye. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 58, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe, D.C.; Holekamp, N.; Siegfried, C.; Shui, Y.B. Vitreoretinal influences on lens function and cataract. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, G.R.; Werness, P.G.; Zollman, P.E.; Brubaker, R.F. Ascorbic acid levels in the aqueous humor of nocturnal and diurnal mammals. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1986, 104, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinvold, A. The significance of ascorbate in the aqueous humour protection against UV-A and UV-B. Exp. Eye Res. 1996, 62, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, A.I.R.N.A.; Nunes, F.M.; Gonçalves, B.; Bennett, R.N.; Silva, A.P. Effect of cooking on total vitamin C contents and antioxidant activity of sweet chestnuts. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, R.F.; Bourne, W.M.; Bachman, L.A.; McLaren, J.W. Ascorbic acid content of human corneal epithelium. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 1681–1683. [Google Scholar]

- Talluri, R.S.; Katragadda, S.; Pal, D.; Mitra, A.K. Mechanism of Lascorbic acid uptake by rabbit corneal epithelial cells: Evidence for the involvement of sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2. Curr. Eye Res. 2006, 31, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.I.; Spector, A. Oxidation-reduction reactions involving ascorbic acid and the hexosemonophosphate shunt in corneal epithelium. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1971, 10, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, S.D.; Kumar, S.; Richards, R.D. Light-induced damage to ocular lens cation pump: Prevention by vitamin C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 3504–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corti, A.; Pompella, A. Cellular pathways for transport and efflux of ascorbate and dehydroascorbate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 500, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, D.L. Ascorbic acid and the eye. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 1198S–1202S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pehlivan, F.E. Vitamin C-an antioxidant agent. In Vitamin C; Hamza, A.H., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, G.; Godin, J.-R.; Pagé, B. The genetics of vitamin C loss in vertebrates. Curr. Genom. 2011, 12, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikimi, M.; Yagi, K. Molecular basis for the deficiency in humans of gulonolactone oxidase, a key enzyme for ascorbic acid biosynthesis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 1203S–1208S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linetsky, M.; Shipova, J.; Cheng, R.; Ortwerth, B.J. Glycation by ascorbic acid oxidation products leads to the aggregation of lens proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1782, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppenol, W.H.; Hider, R.H. Iron and Redox Cycling. Do’s and Don’ts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, L.; Nilsson, S.; Ver Hoeve, J.; Wu, S.Y.; Kaufman, P.; Alm, A. Adler’s Physiology of the Eye, 9th ed.; Mosby-Year Book Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bassnett, S.; Shi, Y.; Vrensen, G.F. Biological glass: Structural determinants of eye lens transparency. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 1250–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civan, C.W.D.M. Basis of chloride transport in ciliary epithelium. J. Membr. Biol. 2004, 200, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaguchi, H.; Tokui, T.; Mackenzie, B.; Berger, U.V.; Chen, X.Z.; Wang, Y.; Brubaker, F.; Hediger, M.A. A family of mammalian Na+-dependent L-ascorbic acid transporters. Nature 1999, 399, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Kim, Y.J.; Martis, R.M.; Donaldson, P.J.; Lim, J.C. Characterisation of glutathione export from human donor lenses. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, R.; Stolz, A.; Ji, Q.; Prasad, P.D.; Ganapathy, V. Vitamin C Transport in Human Lens Epithelial Cells: Evidence for the Presence of SVCT. Exp. Eye Res. 2001, 73, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Oka, M.; Mitsuishi, A.; Bando, M.; Takehana, M. Quantitative analysis of ascorbic acid permeability of aquaporin 0 in the lens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 415, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Oka, M.; Bando, M.; Inoue, T.; Takehana, M. The role of ascorbic acid transporter in the lens of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Biomed. Prev. Nutr. 2011, 1, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, H.L.; Zolot, S.L. Transport of vitamin C in the lens. Curr. Eye Res. 1987, 6, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.C.; Perwick, R.D.; Li, B.; Donaldson, P.J. Comparison of the Expression and Spatial Localization of Glucose Transporters in the Rat, Bovine and Human Lens. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xiong, J.; Hu, J.; Ran, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y. Vitamin C and risk of age-related cataracts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 11, 8929–8940. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. Cataract: Relationship between nutrition and oxidation. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1993, 12, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Jacques, P.F.; Chylack, L.T.J.; Hankinson, S.E.; Khu, P.M.; Rogers, G.; Friend, J.; Tung, W.; Wolfe, J.K.; Padhye, N.; et al. Long-term intake of vitamins and carotenoids and odds of early age-related cortical and posterior subcapsular lens opacities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, M.P.; Fletcher, A.E.; De Stavola, B.L.; Vioque, J.; Alepuz, V.C. Vitamin C is associated with reduced risk of cataract in a Mediterranean population. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Liang, G.; Cai, C.; Lv, J. Association of vitamin C with the risk of age-related cataract: A meta-analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016, 94, e170–e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.B.; Bhat, K.S. Protection against UVB inactivation (in vitro) of rat lens enzymes by natural antioxidants. Mol. Cell Biochem. 1999, 194, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.; Lu, M.; Dudek, E.; Reddan, H.; Taylor, A. Vitamin C and vitamin E restore the resistance of GSH-depleted lens cells to H2O2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, K.R.; Varma, S.D. Protective effect of ascorbate against oxidative stress in the mouse lens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1670, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R.; Feng, Q.; Ortwerth, B.J. LC-MS display of the total modified amino acids in cataract lens proteins and in lens proteins glycated by ascorbic acid in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1762, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ortwerth, B.J.; Olesen, P.R. Ascorbic acid induced crosslinking of lens proteins: Evidence supporting a Maillard reaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1988, 956, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensch, K.G.; Fleming, G.J.E.; Lohmann, W. The role of ascorbic acid in senile cataract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 7193–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortwerth, B.J.; Feather, M.S.; Olesen, P.R. The precipitation and cross-linking of lens crystallins by ascorbic acid. Exp. Eye Res. 1988, 47, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.N.; Giblin, F.J.; Lin, L.R.; Chakrapani, B. The effect of aqueous humor ascorbate on ultraviolet B induced DNA damage in lens epithelium. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998, 39, 344–350. [Google Scholar]

- Blondin, J.; Baragi, V.J.; Schwartz, E.; Sadowski, J.; Taylor, A. Delay of UV induced eye lens protein damage in guinea pigs by dietary ascorbate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1986, 2, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devamanoharan, P.S.; Henein, M.; Morris, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Richards, R.D.; Varma, S.D. Prevention of selenite cataract by vitamin C. Exp. Eye Res. 1991, 52, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Hashizume, K.; Kishimoto, S.; Tezuka, Y.; Nishigori, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Kondo, Y.; Maruyama, N.; Ishigami, A.; Kurosaka, D. Effect of vitamin C depletion on UVR-B induced cataract in SMP30/GNL knockout mice. Exp. Eye Res. 2012, 94, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkaya, D.; Naziroğlu, M.; Armağan, A.; Demirel, A.; Köroglu, B.K.; Çolakoğlu, N.; Kükner, A.; Sönmez, T.T. Dietary vitamin C and E modulates oxidative stress induced-kidney and lens injury in diabetic aged male rats through modulating glucose homeostasis and antioxidant systems. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2011, 29, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linklater, H.A.; Dzialoszynski, T.; McLeod, H.L.; Sanford, S.E. Modelling cortical cataractogenesis. XI. Vitamin C reduces gamma-crystallin leakage from lenses in diabetic rats. Exp. Eye Res. 1990, 51, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naziroğlu, M.; Dilsiz, N.; Cay, M. Protective role of intraperitoneally administered vitamins C and E and selenium on the levels of lipid peroxidation in the lens of rats made diabetic with streptozotocin. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1999, 70, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Reneker, L.W.; Obrenovich, M.E.; Strauch, C.; Cheng, R.; Jarvis, S.M.; Ortwerth, B.J.; Monnier, V.M. Vitamin C mediates chemical aging of lens crystallins by the Maillard reaction in a humanized mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 16912–16917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, V.C.; Kakar, M.; Elfving, A.; Lofgren, S. Drinking water supplementation with ascorbate is not protective against UVR-B-induced cataract in the guinea pig. Acta Opthalmol. 2008, 86, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Sell, D.R.; Hao, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, B.; Wesson, D.W.; Siedlak, S.; Zhu, X.; Kavanagh, T.J.; Harrison, F.E.; et al. Vitamin C is a source of oxoaldehyde and glycative stress in age-related cataract and neurodegenerative diseases. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.L.W.; Ortwerth, B.J. The non-oxidative degradation of ascorbic acid at physiological conditions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1501, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Lin, B.; Ortwerth, B.J. Rate of formation of AGEs during ascorbate glycation and during aging in human lens tissue. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1587, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Prabhakaran, M.; Ortwerth, B.J. The glycation and cross-linking of isolated lens crystallins by ascorbic acid. Exp. Eye Res. 1992, 55, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Mossine, V.; Ortwerth, B.J. The relative ability of glucose and ascorbate to glycate and crosslink lens proteins in vitro. Exp. Eye Res. 1998, 67, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, F.; Obrenovich, M.; Monnier, V.M. Structure and mechanism of formation of human lens fluorophore LM-1. Relationship to vesperlysine A and the advanced Maillard reaction in aging, diabetes, and cataractogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 20796–20804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, R.H.; Shamsi, F.A.; Huber, B.; Pischetsrieder, M. Immunochemical detection of oxalate monoalkylamide, an ascorbate-derived Maillard reaction product in the human lens. FEBS Lett. 1999, 453, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.C.; Umapathy, A.; Donaldson, P.J. Tools to fight the cataract epidemic: A review of experimental animal models that mimic age related nuclear cataract. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 145, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.J.; Taylor, A. Nutritional antioxidants and age-related cataract and maculopathy. Exp. Eye Res. 2007, 84, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P.F.; Chylack, L.T., Jr. Epidemiologic evidence of a role for the antioxidant vitamins and carotenoids in cataract prevention. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 53, 352S–355S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P.F.; Taylor, A.; Hankinson, S.E.; Willett, W.C.; Mahnken, B.; Lee, Y.; Vaid, K.; Lahav, M. Long-term vitamin C supplement use and prevalence of early age-related lens opacities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 66, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperduto, R.D.; Hu, T.; Milton, R.C.; Zhao, J.; Everett, D.F.; Cheng, Q.; Blot, W.J.; Bing, L.; Taylor, P.R.; Jun-Yao, L.; et al. The Linxian cataract studies. Two nutrition intervention trials. Clin. Trial Arch. Ophthalmol. 1993, 111, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebocontrolled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E and beta carotene for age-related cataract and vision loss: AREDS report No. 9. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 1439–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chylack, L.T., Jr.; Brown, N.P.; Bron, A.; Hurst, M.; Köpcke, W.; Thien, U.; Schalch, W. The Roche European American Cataract Trial (REACT): A randomized clinical trial to investigate the efficacy of an oral antioxidant micronutrient mixture to slow progression of age-related cataract. Clin. Trial Ophthal. Epidemiol. 2002, 9, 49–80. [Google Scholar]

- Christen, W.G.; Glynn, R.J.; Sesso, H.D.; Kurth, T.; MacFadyen, J.; Bubes, V.; Buring, J.E.; Manson, J.E.; Gaziano, J.M. Age-related cataract in a randomized trial of vitamins E and C in men. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautiainen, S.; Lindblad, B.E.; Morgenstern, R.; Wolk, A. Vitamin C supplements and the risk of age-related cataract: A population-based prospective cohort study in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng Selin, J.; Rautiainen, S.; Lindblad, B.E.; Morgenstern, R.; Wolk, A. High-dose supplements of vitamins C and E, low-dose multivitamins, and the risk of age-related cataract: A population-based prospective cohort study of men. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.L.; Gahche, J.J.; Lentino, C.V.; Dwyer, J.T.; Engel, J.S.; Thomas, P.R.; Betz, J.M.; Sempos, C.T.; Picciano, M.F. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003–2006. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, J. Factors affecting the use of dietary supplements by Korean adults: Data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentjes, M.A.; Welch, A.A.; Keogh, R.H.; Luben, R.N.; Khaw, K.T. Opposites don’t attract: High spouse concordance for dietary supplement use in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Kaaks, R.; Linseisen, J.; Rohrmann, S. Consistency of vitamin and/or mineral supplement use and demographic, lifestyle and health-status predictors: Findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Heidelberg cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerer, M.; Johansson, S.E.; Wolk, A. Sociodemographic and health behaviour factors among dietary supplement and natural remedy users. Eur J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouchieu, C.; Andreeva, V.A.; Péneau, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Lassale, C.; Hercberg, S.; Touvier, M. Sociodemographic, lifestyle and dietary correlates of dietary supplement use in a large sample of French adults: Results from the NutriNet-Sante cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 1480–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakur, Y.A.; Tarasuk, V.; Corey, P.; O’Connor, D.L. A comparison of micronutrient inadequacy and risk of high micronutrient intakes among vitamin and mineral supplement users and nonusers in Canada. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P.F.; Chylack, L.T., Jr.; Hankinson, S.E.; Khu, P.M.; Rogers, G.; Friend, J.; Tung, W.; Wolfe, J.K.; Padhye, N.; Willett, W.C.; et al. Long-term nutrient intake and early age-related nuclear lens opacities. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Wu, J.; Cho, E.; Ogata, S.; Jacques, P.; Taylor, A.; Chiu, C.; Wiggs, J.L.; Seddon, J.M.; Hankinson, S.E.; et al. Contribution of the Nurses’ Health Study to the Epidemiology of Cataract, Age-Related Macular Degeneration, and Glaucoma. Rev. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.D.; Vashist, P.; Gupta, S.K.; Young, I.S.; Maraini, G.; Camparini, M.; Jayanthi, R.; John, N.; Fitzpatrick, K.E.; Chakravarthy, U. Inverse association of vitamin C with cataract in older people in India. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 1958–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Valero, M. Fruit and vegetable intake and vitamins C and E are associated with a reduced prevalence of cataract in a Spanish Mediterranean population. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares-Perlman, J.A.; Lyle, B.J.; Klein, R.; Fisher, A.I.; Brady, W.E.; Vanden-Langenberg, G.M.; Trabulsi, J.N.; Palta, M. Vitamin supplement use and incident cataracts in a population-based study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2000, 118, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulou, S.; Samoli, E.; Theodossiadis, P.G.; Papathanassiou, M.; Lagiou, A.; Lagiou, P.; Tzonou, A. Diet and cataract: A case–control study. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2014, 34, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, J.A.; Voland, R.; Adler, R.; Tinker, L.; Millen, A.E.; Moeller, S.M.; Blodi, B.; Gehrs, K.M.; Wallace, R.B.; Chappell, R. Healthy diets and the subsequent prevalence of nuclear cataract in women. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunis, S.W.; Brownlow, M.D.; Schmidt, E.E. The Post-Vitrectomy Lenstatin™ Study: A Randomized Double Blind Human Clinical Trial Testing the Efficacy of Lenstatin, an Oral Antioxidant Nutritional Supplement, in Inhibiting Nuclear Cataract Progression After Pars Plana Vitrectomy. EC Ophthalmol. 2018, 95, 299–307. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Method of Cataract Induction | Type of Cataract | Vitamin C Elevation or Depletion | Parameters Measured | Outcome | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro studies | Rats Wistar/NIN inbred strain (3 months old) | Irradiation of lenses at 300 nm for 24 h | No lens opacification | Lenses irradiated in media containing 2 mM ascorbic acid or 2 μM α-tocopherol acetate or 10 μm β-carotene | -Enzyme activity of glycolysis pathways (hexokinase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, aldose reductase) -Na, K- ATPase activity -Lipid peroxidation | Addition of ascorbic acid or α-tocopherol or β-carotene to the media, reduced lipid peroxidation and increased activities of enzyme involved in the glycolysis hexomonophosphate pathway | [86] |

| Rabbit lens epithelial cells | Buthionine sulfoximine | Not reported. Lenses exhibited a depletion of ~75% GSH | Cells were cultured in 25–50 µM vitamin C or 5–40 µM vitamin E at the same time as BSO treatment for 24 h and then exposed to H2O2 for 1 h | -Cell viability: MTS assay, LDH assay -GSH/GSSG levels | Supplementation of vitamin C and vitamin E protects GSH-depleted lens epithelial cells by reducing levels of GSSG | [87] | |

| Mice CD-1 (25g) | Lenses were cultured in xanthine, xanthine oxidase, and uricase | Not stated | Lenses were cultured in 2 mM ascorbate and ROS-inducing reagents along with 86RbCl | -Membrane transport activity -ATP levels -GSH levels | ROS agents decreased membrane transport activity, ATP and GSH. Ascorbate minimized these effects significantly | [88] | |

| Calf lenses | NA | NA | Water-insoluble proteins from aged normal human lenses, early stage brunescent cataract lenses and calf lens proteins were reacted with or without 20 mM ascorbate in air for 4 weeks | -Protein modifications (glycation reactions) | AGEs present in aged and cataractous human lenses eluted at the same retention times as those from ascorbic acid glycated calf lens proteins, suggesting that the yellow chromophores in brunescent lenses represent AGEs due to ascorbic acid glycation | [37] | |

| Water-insoluble proteins from aged normal human lenses, early stage brunescent cataract lenses and calf lens proteins were reacted with or without 20 mM ascorbate in air for 4 weeks | -Amino acid modifications -Protein modifications (glycation reactions) | LC-MS revealed that the majority of the major modified amino acids present in early stage brunescent cataract lens proteins were as a result of ascorbic acid modification | [89] | ||||

| Incubation of calf lens extracts with either 10 mM ascorbic acid, 20 mM sorbitol, or 20 mM glucose for 8 weeks | -Protein precipitation and browning -Cross linking of proteins -Protein modifications (glycation) | Only ascorbic acid induced the formation of high molecular weight aggregates with extensive browning | [90] | ||||

| Bovine lens crystallin proteins | NA | NA | Bovine lens crystallin proteins incubated with [14C] ascorbic acid for 1 month and the fluorescence spectrum compared to human cataractous lenses | -Browning -Binding of Ascorbic Acid Oxidation Products to Proteins. -Comparison of fluorescence Spectra | Formation of brown condensation products correlated with increased protein radioactivity. Fluorescence spectrum of condensation products was similar to spectrum of human cataractous lenses | [91] | |

| Bovine lens β-crystallin incubated with increasing concentrations of sugars and sugar derivatives for a period of 2 weeks in the dark at 37 °C | -Protein precipitation and browning -Cross linking of proteins | Protein precipitation and browning reaction was observed with both vitamin C and DHA. No reaction was seen with several other sugars suggesting that vitamin C is a significant glycating agent | [92] | ||||

| In vivo studies | Guinea pigs (between 280 and 320 g) | UV-B (0.25–0.75 J/cm2) 10 min exposure time | Not mentioned | Vitamin C depletion via guinea pigs fed an ascorbate-deficient diet | -DNA damage (DNA single strand breaks) | Lenses from ascorbate deficient guinea pigs showed 50% more DNA damage than those from normal guinea pigs after UV exposure | [93] |

| Rats Harlan Sprague-Dawley (300 g) | UV-B (0.25–0.75 J/cm2) 10 min exposure time | Not mentioned | IP injections of sodium ascorbate (1 g/kg) | -DNA damage (DNA single strand breaks) | Increase in vitamin C in AH and lenses; 50% decrease in UV-induced DNA strand breaks compared to non-ascorbate injected rats | [93] | |

| Guinea pigs (56 days old, 500–600 gm each) | NA | NA | High dietary ascorbate (50 mg/day) vs. low dietary ascorbate (2 mg/day) for 21 weeks. Lens homogenates exposed to UV light. | -Protein damage (high-molecular-weight aggregates and enhanced loss of exopeptidase activity) | Markers of light-induced protein damage were reduced in the HDA animals compared to LDA animals | [94] | |

| Rat Sprague-Dawley (p8-p21) | IP admin of sodium selenite at postnatal day 10 | Nuclear | Daily IP dose of sodium ascorbate (0.3 mmol) at postnatal day 8 until postnatal day 25 | -ATP -GSH -MDA -Soluble protein -Lens transparency | Ascorbate was able to restore ATP and GSH levels and reduced MDA levels that were altered in sodium selenite lenses. Significantly reduced cataracts in animals administered with ascorbate | [95] | |

| Senescence marker protein-30 knockout (KO) mice | UVR-B (200 mW/cm2) for 100 s twice a week for 3 weeks | Anterior subcapsular cataract | Fed a vitamin C sufficient diet (1.5 g/L) or vitamin C deficient diet (0.0375 g/L) and then exposed to UV-B | -Lens morphology -Protein content -Lens transparency | Less extensive opacities | [96] | |

| Rats Wistar (18–20 months) | Streptozotocin | Cortical | STZ diabetic rats were fed a Vitamin C (1 g ascorbate/kg feed) and vitamin E (600 mg dl-α-tocopherol acetate/kg feed) supplemented diet | -Lipid peroxidation -GSH -GSH-Px activity | Lowered lipid peroxidation levels in the lens Increased GSH-Px activity No mention of effects on lens opacities | [97] | |

| Rats Wistar (age not specified) | Streptozotocin | Cortical | STZ diabetic rats were fed vitamin C at 0%, 0.3%, and 1.0% (w/w) to rodent chow | -Membrane integrity -ATP -Lens transparency | Treatment of diabetic group with vit C at 0.3% and 1% lead to decrease in leakage of γ-crystallins into the aqueous and vitreous humor. A reduction in cataract was detected for the 1% dietary vitamin C group | [98] | |

| Rats Wistar (12 weeks) | Streptozotocin | Cortical | IP administered with vitamin E (20 mg over 24 h), selenium (0.3 mg over 24 h), vitamin E (20 mg) and selenium combination (0.3 mg over 24 h), or vitamin C (30 mg over 24 h). On the fourth day after injection, IP injections of STZ were administered. | -MDA -GSH -GPx activity | Vitamins C and E and selenium can protect the lens against oxidative damage, but the effect of vitamin C appears to be much greater than that of vitamin E and selenium. No mention of lens opacities | [99] | |

| Transgenic mouse in which SVCT2 is overexpressed | NA | At 12 months of age, transgenic lenses were a yellow colour similar to that observed in older human lenses | Transgenic lenses contained 10-fold greater vitamin C and 25-fold more DHA than WT lenses | -Protein modifications | Transgenic lenses contained increased levels of vitamin C derived advanced ascorbylation end products which are also known to be present in the aging human lens | [100] | |

| Guinea pigs (6–9 weeks) | UVR-B (80 kJ/m2) | Superficial anterior cataract | Drinking water supplemented with or without 5.5 mm l-ascorbate for 4 weeks. After supplementation, animals were exposed in vivo to 80 kJ/m2 UVR-B. | -Lens transparency via forward light scattering measurements | Cataract develops in lenses exposed to UVR-B both in animals given drinking water that is supplemented with ascorbate and those whose drinking | [101] |

| Study, Type | Nutrients | Population | Disease Outcome | Results | Year, Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-related cataract in a randomized trial of vitamins E and C in men. Eight years of treatment and follow-up RCT | Vitamin E 400 IU or placebo on alternate days and vitamin C 500 mg of or placebo daily | Participants: 11,545 United States male ≥50 years | Incidence of age-related cataract | No significant beneficial or harmful effect on the risk of cataract. HR 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.91–1.14 | [116] |

| The Swedish mammography cohort study follow up. 8.2 years of follow-up Population-based, prospective cohort of women. | Vitamin C (approximately 1 g) Vitamin c within a multivitamin supplement (approximately 60 mg) | Participants: 24,593 Sweden female 49–83 years | Incidence of age-related cataracts | The use of vitamin C supplements may be associated with a higher risk of age-related cataract among women. The multivariable HR for vitamin C supplement vs. nonusers was 1.25 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.50). The HR for the duration of 10 y of use before baseline was 1.46 (95% CI: 0.93, 2.31). The HR for the use of multivitamins containing vitamin C was 1.09 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.25). | [117] |

| High-dose Supplements of Vitamins C and E, Low-Dose Multivitamins, and the Risk of Age-Related Cataract Follow-up of 8.4 years Cohort | Vitamin C and vitamin E as single supplements was estimated to be 1 g and 100 mg, respectively. Multivitamins were estimated to contain 60 mg of vitamin C and 9 mg of vitamin E | Participants: 31,120 Sweden male 45–79 years | Risk of age-related cataract | Use of high-dose (but not low-dose) single vitamin C supplements increased the risk of age-related cataract. The multivariable- adjusted HR for men using vitamin C supplements only was 1.21 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.04, 1.41) in a comparison with that of non-supplement users. The HR for long-term vitamin C users (≥10 years before baseline) was 1.36 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.81). The risk of cataract with vitamin C use was stronger among older men (>65 years) (HR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.41, 2.60) and corticosteroid users (HR = 2.11, 95% CI: 1.48, 3.02) | [118] |

| Study, Design | Nutrients Studied | Population | Disease Outcome | Results | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The India Study of Age-related Eye Disease (INDEYE study) a population-based study. Cross-sectional analytic study | Vitamin C and inclusion of other antioxidants (lutein, zeaxanthin, retinol, β-carotene, and α-tocopherol) | Participants:5638 North and South India Male and female ≥60 years | Incidence of cataract in the Indian setting | Vitamin C was inversely associated with cataract (adjusted OR for highest to lowest quartile = 0.61; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.51–0.74; p = 1.1 × 10−6). Similar results were seen by type of cataract: nuclear cataract (adjusted OR 0.66; CI, 0.54–0.80; p = 0.0001), cortical cataract (adjusted OR 0.70; CI, 0.54–0.90; p = 0.002), and PSC (adjusted OR 0.58; CI, 0.45–0.74; p = 0.00003) | [128] |

| Healthy Diets and the Subsequent Prevalence of Nuclear Cataract in Women. Participated in the Carotenoids in Age-Related Eye Disease Study—7 years follow up | Vitamin C (40 vs. 207 mg/d); vitamin E (3 vs. 11 mg/d) | Participants: 1808 United States female 50–79 years | Prevalence of nuclear cataract in women. | Adjustment of the OR for nuclear cataract among women with high vs. low HEI-95 scores, for vitamin C intake from foods attenuated the ORs (Multivariate OR (95%CI) = 0.76 (0.50–1.15), suggesting that higher vitamin C intakes partly explained the associations with HEI-95 dietary assessment. There was a significant linear trend for a protective association of vitamin C intake from foods | [132] |

| The European Eye Study (EUREYE study). Recruited during 1-year period. Multi-center cross-sectional population-based study | Carotenoids, vitamins C (107 mg/d) and E | Participants: 599 Spain Male/female ≥65 years | Prevalence of cataract with fruit and vegetable intake | High daily intakes of fruit and vegetables and vitamin c were associated with a significantly decreased prevalence of cataract or cataract surgery (p for trend = 0.008). Increasing quartiles of dietary intakes from 107 mg/d of vitamin C showed a significant decreasing association with prevalence of cataract or cataract extraction (p for trend = 0.047) | [129] |

| Diet and cataract. Case-control study | Carbohydrates carotene vitamins C and E | Participants: 314 cataract cases and 314 controls Greece Male/Female 45–85 years | Association between diet and risk of cataract in Athens | There was a protective association between cataract risk and intake of vitamin c (OR = 0.50, p \ 0.001 for cataract overall; OR = 0.55, p \ 0.001 for nuclear cataract; OR = 0.30, p\0.001 for PSC) | [131] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, J.C.; Caballero Arredondo, M.; Braakhuis, A.J.; Donaldson, P.J. Vitamin C and the Lens: New Insights into Delaying the Onset of Cataract. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103142

Lim JC, Caballero Arredondo M, Braakhuis AJ, Donaldson PJ. Vitamin C and the Lens: New Insights into Delaying the Onset of Cataract. Nutrients. 2020; 12(10):3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103142

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Julie C, Mariana Caballero Arredondo, Andrea J. Braakhuis, and Paul J. Donaldson. 2020. "Vitamin C and the Lens: New Insights into Delaying the Onset of Cataract" Nutrients 12, no. 10: 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103142

APA StyleLim, J. C., Caballero Arredondo, M., Braakhuis, A. J., & Donaldson, P. J. (2020). Vitamin C and the Lens: New Insights into Delaying the Onset of Cataract. Nutrients, 12(10), 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103142