Effects of Advertising on Food Consumption Preferences in Children

Abstract

:1. Introduction

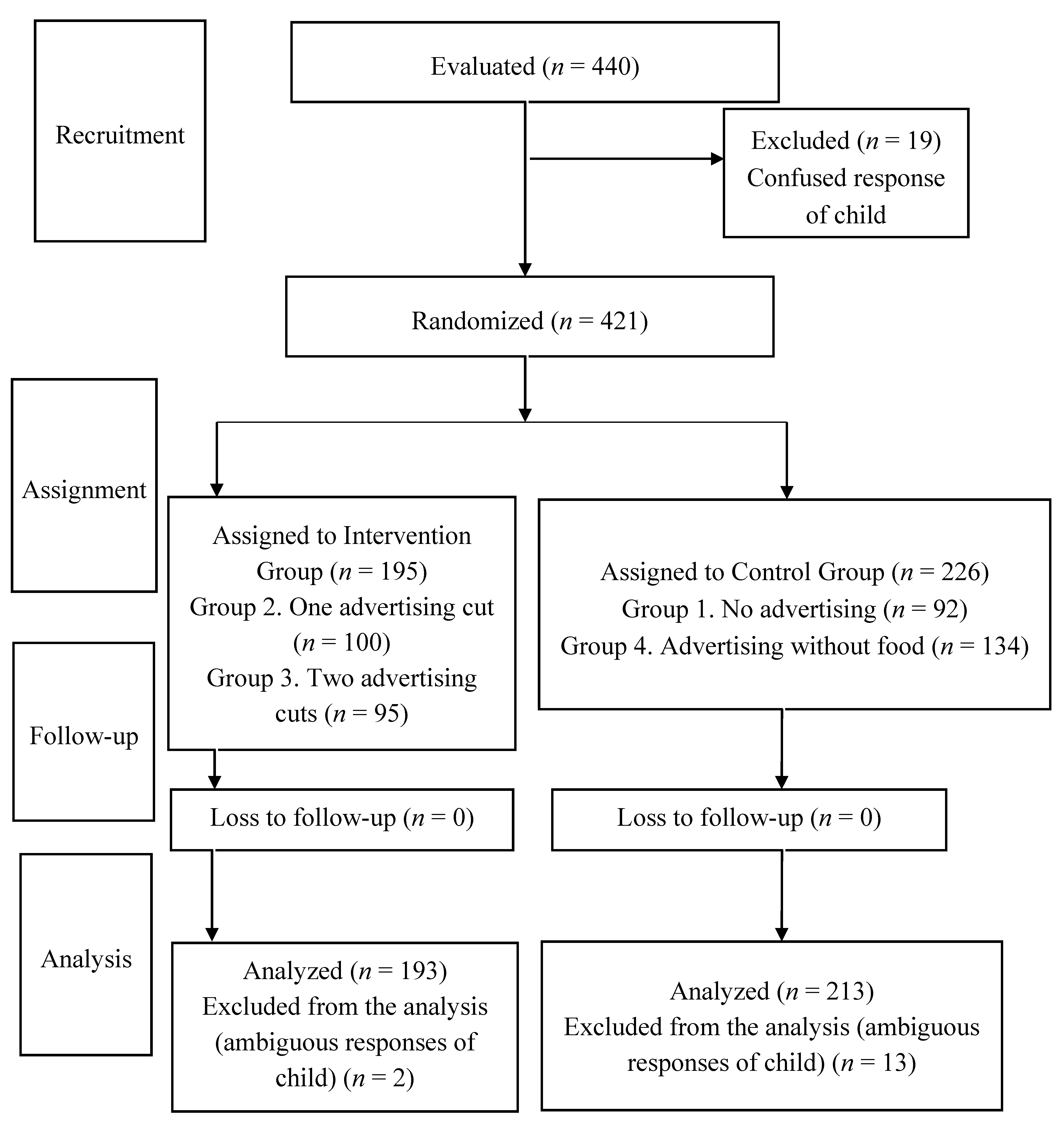

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

2.2. Procedure

- ✓

- Commercials of high fat and/or sugar content food products aimed at a child audience.

- ✓

- Products aimed to be consumed at breakfast and included in the most frequently announced food groups: sugared cereals, cookies, cocoa, and dairy products.

- ✓

- Including some commercial which employs special effects or fantastic situations, another which promotes giving some gift, collectible, or present, and a third one which uses the testimony of some famous character.

- Third commercial: “Miel Pops” cereals.Final voiceover with a slogan: “Mielpops, el desayuno más pop” (“Mielpops, the most pop breakfast”). Spot based on the use of shocking images and on fantastic situations by means of animation techniques.

- Fourth commercial: “Príncipe Double Choc” chocolate cookies.Spot in which a famous Spanish soccer player explains the benefit of the product or his experiences related with it: “I like them with a lot of chocolate cream, like my Príncipe Double Choc”. This is a testimonial spot which uses the words of a celebrity as an advertising resource.

- First commercial: “Puleva®” cocoa shakes.Final voiceover saying: “Descubre el Club Batidos Puleva y podrás ganar Play Stations, juegos Sing Star y miles de regalos” (“Discover the Puleva Shake Club and you can win Play Stations, Sing Star games, and thousands of presents”). Advertising version: “Estos batidos son algo especial: Son batidos Puleva” (“These shakes are something special. They are Puleva shakes”). Spot based on music and on visual experimentation.

- Second commercial: “Bollycao” chocolate-filled roll.Final voiceover saying: “Ahora con los Bollycao únete a la banda de ‘Los Simpsons’ con los ‘bollytransfer’” (“Now with the Bollycaos, join the ‘The Simpsons’ gang with the ‘bollytransfers’”). Spot based on music and on visual experimentation. It also presents a gift inside the wrapping, a “bollytransfer”, which is a sticker with a character from “The Simpsons”.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emond, J.A.; Longacre, M.R.; Drake, K.M.; Titus, L.J.; Hendricks, K.; MacKenzie, T.; Harris, J.L.; Carroll, J.E.; Cleveland, L.P.; Gaynor, K.; et al. Influence of child-targeted fast food TV advertising exposure on fast food intake: A longitudinal study of preschool-age children. Appetite 2019, 140, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund International. NOURISHING Framework: Restrict Food Advertising and Other Forms of Commercial Promotion; World Cancer Research Fund International: London, UK, 2016; Available online: http://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-framework/restrict-food-marketing (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: A pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 2016, 387, 1377–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. Prevalencia de Sobrepeso y Obesidad en ESPAÑA en el Informe “The Heavy Burden of Obesity (OCDE 2019) y en Otras Fuentes de Datos; Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Recommendations from a Pan American Health Organization Expert Consultation on the Marketing of Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children in the Americas; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. A Framework for Implementing the Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, F.J.; Bell, J.F. Associations of television content type and obesity in children. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.K.; Yoon, J.; Chung, S.J. Effects of exposure to television advertising for energy-dense/ nutrient-poor food on children’s food intake and obesity in South Korea. Appetite 2014, 81, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenheck, R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: A systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraak, V.L.; Story, M. Influence of food companies’ brand mascots and entertainment companies’ cartoon media characters on children’s diet and health: A systematic review and research needs. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poor, M.; Duhachek, A.; Krishnan, H.S. How images of other consumers influence subsequent taste perceptions. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, T.L.; van Baaren, R. Human mimicry. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 41, 219–274. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, R.S.; Krishna, A. The “visual depiction effect” in advertising: Facilitating embodied mental simulation through product orientation. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papies, E.K. Tempting food words activate eating simulations. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, L.M.; Schermbeck, R.M.; Chaloupka, F.J. Nutritional content of food and beverage products in television advertisements seen on children’s programming. Child. Obes. 2013, 9, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, S.; Kunkel, D.; Mermin, S.E. Government can regulate food advertising to children because cognitive research shows that it is inherently misleading. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Neijens, P.C.; Smit, E.G. A new branch of advertising reviewing factors that influence reactions to product placement. J. Advert. Res. 2009, 49, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.D.; Carruthers Den Hoed, R.; Conlon, M.J. Food branding and young children’s taste preferences: A reassessment. Can. J. Public Health 2013, 104, e364–e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, H.; Niven, P.; Scully, M.; Wakefield, M. Food marketing with movie character toys: Effects on young children’s preferences for unhealthy and healthier fast food meals. Appetite 2017, 117, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, R.; Fuentes-García, A. The effects of TV unhealthy food brand placement on children. Its separate and joint effect with advertising. Appetite 2015, 91, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, S.; Elliott, C. Measuring the impact of product placement on children using digital brand integration. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2013, 19, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reijmersdal, E.; Jansz, J.; Peters, O.; van Noort, G. The effects of interactive brand placements in online games on children’s cognitive, affective, and conative brand responses. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Blandón, J.A.; Deitos-Vasquez, M.E.; Romero-Castillo, R.; da Rosa-Viana, D.; Robles-Romero, J.M.; Mendes-Lipinski, J. Sedentary Behaviors of a School Population in Brazil and Related Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2020, 17, 6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía. Estadísticas Avance Curso 2011/2012; Consejería de Educación: Sevilla, Spain, 2012.

- Borzekowski, D.L.G.; Robinson, T.N. The 30-Second Effect: An Experiment Revealing the Impact of Television Commercials on Food Preferences of Preschoolers. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2001, 101, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Blandón, J.A.; Pabón-Carrasco, M.; Lomas-Campos, M.M. Análisis de contenido de la publicidad de productos alimenticios dirigidos a la población infantile. Gac. Sanit. 2017, 31, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponce-Blandón, J.A.; Pabón-Carrasco, M.; Lomas-Campos, M.M. Contents Analysis of Food Advertisements Addressed to Children and Adults in Adalusia. Nurs. Advan. Health Care 2017, 1, 006. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Rubio, A.; Soto-Moreno, A.M. Plan Integral de Obesidad Infantil de Andalucía: 2007–2012; Consejería de Salud Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anschutz, D.J.; Engels, R.C.; van Strien, T. Side effects of television food commercials on concurrent nonadvertised sweet snack food intakes in young children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harris, J.L.; Bargh, J.A. The relationship between Television Viewing and unhealthy eating: Implications for children and media interventions. Health Commun. 2009, 24, 660–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L.A.; Gwozdz, W.; Barba, G.; de Henauw, S.; Lascorz, N.; Pigeot, I. Experimental evidence on the impact of food advertising on children’s knowledge about and preferences for healthful food. J. Obes. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.; Kelly, B.; McMahon, A.T.; Boyland, E.; Baur, L.A.; Chapman, K.; King, L.; Hughes, C.; Bauman, A. Sustained impact of energy-dense TV and online food advertising on children’s dietary intake: A within-subject, randomized, crossover, counter-balanced trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anschutz, D.J.; Engels, R.C.; van Strien, T. Maternal encouragement to be thin moderates the effect of commercials on children’s snack food intake. Appetite 2010, 55, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, T.B.; McAlister, A.R.; Polmear-Swendris, N. Children’s knowledge of packaged and fast food brands and their BMI. Why then relationship matters for policy makers. Appetite 2014, 81, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Hattersley, L.; King, L.; Flood, V. Persuasive food marketing to children: Use of cartoons and competitions in Australian commercial television advertisements. Health Promot. Int. 2008, 23, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, J.D.; Witherspoon, E.M. The mass media and American adolescents’ health. J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 31, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyland, E.J.; Harrold, J.A.; Kirkham, T.C.; Corker, C.; Cuddy, J.; Evans, D.; Dovey, T.M.; Lawton, C.L.; Blundell, J.E.; Halford, J.C.G. Food commercials increase preference for energy-dense foods, particularly in children who watch more television. Pediatrics 2011, 128, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longacre, M.R.; Drake, K.M.; Titus, L.J.; Harris, J.; Cleveland, L.P.; Langeloh, G.; Hendricks, K.; Dalton, M.A. Child-targeted TV advertising and preschooler’s consumption of high-sugar breakfast cereals. Appetite 2017, 108, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castetbon, K.; Harris, J.L.; Schwartz, M.B. Purchases of ready-to-eat cereals vary across US household sociodemographic categories according to nutritional value and advertising targets. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dixon, H.; Scully, M.; Niven, P.; Kelly, B.; Chapman, K.; Donovan, R.; Martin, J.; Baur, L.A.; Crawford, D.; Wakefield, M. Effects of nutrient content claims, sports celebrity endorsements and premium offers on pre-adolescent children’s food preferences: Experimental research. Pediatr. Obes. 2014, 9, e47–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.M.; Szczpka, G.; Chaloupka, F.J.; Braunschweig, C.L. Nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallez, L.; Qutteina, Y.; Raedschelders, M.; Boen, F.; Smits, T. That’s my cue to eat: Systematic review of the persuasiveness of front-of-pack cues on food packages for children vs. adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendes-Lipinski, J.; Romero-Martín, M.; Jiménez-Picón, N.; Lomas-Campos, M.M.; Romero-Castillo, R.; Ponce-Blandón, J.A. Breakfast Habits among Schoolchildren in the City of Uruguaiana, Brazil. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, e61490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product | Total (N = 421) n (%) | Control Group (n = 200) n (%) | Intervention Group (n = 191) n (%) | RR (CI 95%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair No. 1 Sugary cereals | Advertised: “Miel pops” | 231 (55.3) | 124 (55.6) | 107 (54.9) | 0.98 (0.79–1.21) | 0.8803 |

| Not advertised: “Frostis Kellogg’s” | 187 (44.7) | 99 (44.4) | 88 (45.1) | |||

| Pair No. 2 Chocolate cookies | Advertised: “Príncipe Double Choc” | 184 (43.7) | 100 (44.2) | 84 (43.1) | 1.02 (0.82–1.27) | 0.8091 |

| Not advertised: “Tosta Rica Choco Guay” | 237 (56.3) | 126 (55.8) | 111 (56.9) | |||

| Pair No. 3 Chocolate milkshake | Advertised: “Batidos Puleva” | 270 (64.9) | 147 (65.9) | 123 (63.7) | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 0.6408 |

| Not advertised: “Batidos Pascual” | 146 (35.1) | 76 (34.1) | 70 (36.3) | |||

| Pair No. 4 Buns filled with chocolate | Advertised: “Bollycao” | 212 (51.2) | 102 (46.8) | 106 (56.2) | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 0.0448 |

| Not advertised: “Qé Tentación” | 202 (48.8) | 117 (53.2) | 89 (43.8) |

| Variables | Categories | PAIR No. 1 Sugary Cereals | PAIR No. 2 Chocolate Cookies | PAIR No. 3 Chocolate Milkshake | PAIR No. 4 Buns Filled with Chocolate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Miel pops” | Frosties Kellogg’s | Príncipe Double Choc | Tosta Rica Choco Guay | Milkshake Puleva | Milkshake Pascual | Bollycao | Qé Tentación | ||

| Sex | Boys | 80 (39.8%) | 121 (60.2%) | 133 (65.8%) | 69 (34.2%) | 121 (60.5%) | 79 (39.5%) | 111 (55.5%) | 89 (44.5%) |

| Girls | 151 (69.6%) | 66 (30.4%) | 104 (47.5%) | 115 (52.5%) | 149 (69.0) | 67 (31.0%) | 101 (47.2%) | 113 (52.8%) | |

| RR (CI 95%) p | 1.98 (1.57–2.49) 0.00000 | 1.54 (1.22–1.93) 0.00015 | 1.14 (0.98–1.31) 0.0701 | 0.85 (0.70–1.02) 0.0912 | |||||

| Nationality | Spanish | 214 (55.2%) | 174 (44.8%) | 176 (45.0%) | 215 (55.0%) | 249 (64.5%) | 137 (35.5%) | 202 (52.6%) | 182 (47.4%) |

| Other nationalities | 16 (55.2%) | 13 (44.8%) | 8 (27.6%) | 21 (72.4%) | 20 (69.0%) | 9 (31.0%) | 10 (34.5%) | 19 (65.5%) | |

| RR (CI 95%) p | 1.03 (0.67–1.58) 0.8725 | 1.68 (0.92–3.08) 0.0499 | 0.92 (0.72–1.17) 0.5437 | 1.57 (0.94–2.64) 0.0419 | |||||

| Predictor Variable | Odds Ratio | CI 95% | Coef. | Standard Error | Statistical | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair No. 1 | ||||||

| Group (intervention/control) | 1.084 | (0.69–1.69) | 0.080 | 0.22 | 0.355 | 0.722 |

| Nationality | 0.978 | (0.43–2.17) | −0.021 | 0.40 | −0.052 | 0.958 |

| Sex | 0.285 | (0.19–0.42) | −1.252 | 0.20 | −6.015 | 0.000 |

| Pair No. 2 | ||||||

| Group (intervention/control) | 1.003 | (0.64–1.52) | 0.003 | 0.222 | 0.017 | 0.986 |

| Nationality | 0.383 | (0.27–0.94) | −0.959 | 0.440 | −2.176 | 0.0295 |

| Sex | 0.457 | (0.30–0.68) | −0.781 | 0.204 | −3.822 | 0.0001 |

| Pair No. 3 | ||||||

| Group (intervention/control) | 0.9512 | (0.61–1.48) | −0.050 | 0.2262 | −0.221 | 0.824 |

| Nationality | 1.2738 | (0.55–2.90) | 0.242 | 0.4200 | 0.576 | 0.564 |

| Sex | 0.6803 | (0.45–1.02) | −0.385 | 0.2069 | −1.862 | 0.062 |

| Pair No. 4 | ||||||

| Group (intervention/control) | 1.349 | (0.88–2,06) | 0.299 | 0.217 | 1.376 | 0.168 |

| Nationality | 0.513 | (0.22–1.14) | −0.667 | 0.411 | −1.623 | 0.104 |

| Sex | 1.399 | (0.94–2.07) | 0.336 | 0.199 | 1.683 | 0.092 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ponce-Blandón, J.A.; Pabón-Carrasco, M.; Romero-Castillo, R.; Romero-Martín, M.; Jiménez-Picón, N.; Lomas-Campos, M.d.l.M. Effects of Advertising on Food Consumption Preferences in Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3337. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113337

Ponce-Blandón JA, Pabón-Carrasco M, Romero-Castillo R, Romero-Martín M, Jiménez-Picón N, Lomas-Campos MdlM. Effects of Advertising on Food Consumption Preferences in Children. Nutrients. 2020; 12(11):3337. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113337

Chicago/Turabian StylePonce-Blandón, José Antonio, Manuel Pabón-Carrasco, Rocío Romero-Castillo, Macarena Romero-Martín, Nerea Jiménez-Picón, and María de las Mercedes Lomas-Campos. 2020. "Effects of Advertising on Food Consumption Preferences in Children" Nutrients 12, no. 11: 3337. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113337

APA StylePonce-Blandón, J. A., Pabón-Carrasco, M., Romero-Castillo, R., Romero-Martín, M., Jiménez-Picón, N., & Lomas-Campos, M. d. l. M. (2020). Effects of Advertising on Food Consumption Preferences in Children. Nutrients, 12(11), 3337. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113337