Sugar Content in Processed Foods in Spain and a Comparison of Mandatory Nutrition Labelling and Laboratory Values

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

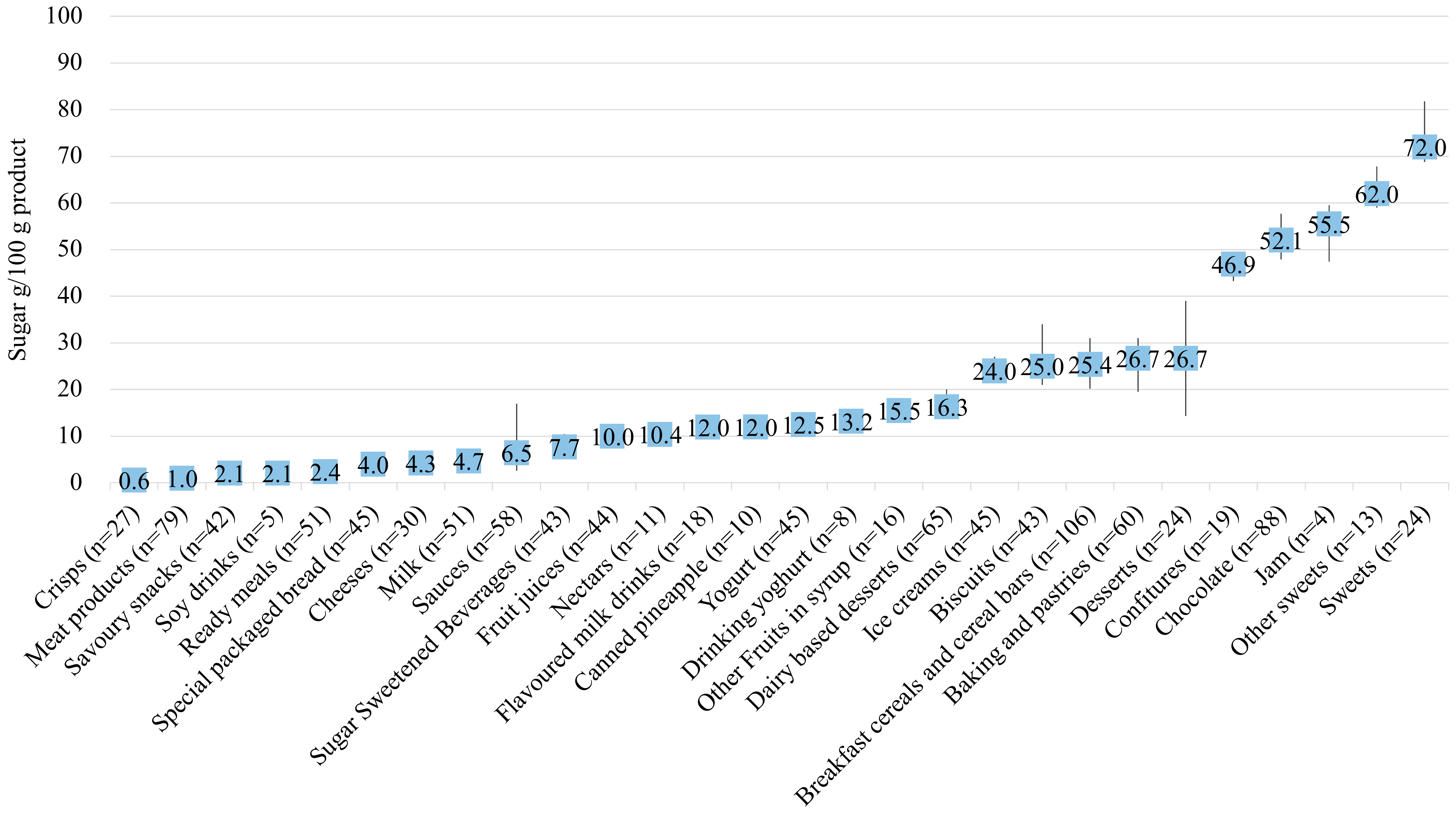

3.1. Descriptive Study of the Total Sugar AV and LV

3.2. Adequacy Study of the LV Based on the EU Labelling Requirements for the Tolerance of the Values Declared on the Label

3.3. Appropriateness Study of Using the LV as Reference Data for Reformulation, Monitoring, and other Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blundell, J.E.; Baker, J.L.; Boyland, E.; Blaak, E.; Charzewska, J.; de Henauw, S.; Frühbeck, G.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Hebebrand, J.; Holm, L.; et al. Variations in the prevalence of obesity among european countries, and a consideration of possible causes. Obes. Facts 2017, 10, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Effects of Dietary Risks in 195 Countries, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017—The Lancet. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(19)30041-8/fulltext (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE). Nutrition and Food Systems. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; Committee on World Food Security: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- White Paper on a Strategy for Europe on Nutrition, Overweight and Obesity Related to Health Issues; COM(2007) 279 Final; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2007.

- EU Framework for National Salt Initiatives. 2008. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/nutrition/documents/salt_initiative.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- EU Framework for National Initiatives on Selected Nutrients. 2009. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/euframework_national_nutrients_en.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Annex I Saturated Fats. EU Framework for National Initiatives on Selected Nutrients. 2012. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/satured_fat_eufnisn_en.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Annex II Added Sugars. EU Framework for National Initiatives on Selected Nutrients. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/added_sugars_en.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Ortega, R.M.; López-Sobaler, A.M.; Ballesteros, J.M.; Pérez-Farinós, N.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.; Aparicio, A.; Perea, J.M.; Andrés, P. Estimation of salt intake by 24 h urinary sodium excretion in a representative sample of Spanish adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Farinós, N.; Dal Re Saavedra, M.Á.; Villar Villalba, C.; Robledo de Dios, T. Trans-fatty acid content of food products in Spain in 2015. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contenido de sal en los Alimentos en España. 2012. Agencia Española de Consumo, Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Madrid; 2015. Available online: http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/estudio_contenido_sal_alimentos.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Trans Fatty Acid Content in Foods in Spain 2010. Spanish Agency for Consumer Affairs, Food Safety and Nutrition; Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Madrid; 2014. Available online: http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/Informe_ingles_Contenido_AGT_alimentos_2010_ingles.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Trans Fatty Acid Content in Food in Spain 2015. Spanish Agency for Consumer Affairs, Food Safety and Nutrition; Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Madrid; 2016. Available online: http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/Informe_AGT2015_Ingles.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Reformulacion de Alimentos. Convenios y Acuerdos; Aecosan—Agencia Española de Consumo, Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. Available online: http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/web/nutricion/ampliacion/reformulacion_alimentos.htm (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Pérez Farinós, N.; Santos Sanz, S.; Dal Re, M.Á.; Yusta Boyo, J.; Robledo, T.; Castrodeza, J.J.; Campos Amado, J.; Villar, C. Salt content in bread in Spain, 2014. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estudio ENALIA 2012–2014: Encuesta Nacional de Consumo de Alimentos en Población Infantil y Adolescente. Agencia Española de Consumo, Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Madrid; 2017. Available online: http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/seguridad_alimentaria/gestion_riesgos/Informe_ENALIA2014_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- García, M. Informe 2015 del Mercado de Supermercados—Informes y Reportajes de Alimentación en Alimarket, Información Económica Sectorial. Available online: http://www.alimarket.es/alimentacion/informe/182798/informe-2015-del-mercado-de-supermercados (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Orden de 18 de Julio de 1989 por la que se Aprueban los Métodos Oficiales de Análisis para el Control de Determinados Azúcares Destinados al Consumo Humano. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-1989-17511 (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Laying Down Community Methods of Analysis for Testing Certain Sugars Intended for Human Consumption; The Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 1979; 79/78 6/EEC.

- Joint Action on Nutrition and Physical Activity (JANPA). Work Package 5 Nutritional Information Monitoring and Food Reformulation Prompting; European Commission 3rd Health Programme (2014-2020): Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Menard, C.; Dumas, C.; Goglia, R.; Spiteri, M.; Gillot, N.; Combris, P.; Ireland, J.; Soler, L.G.; Volatier, J.L. OQALI: A French database on processed foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidance Document for Competent Authorities for the Control of Compliance with EU Legislation with Regard to the Setting of Tolerances for Nutrients Values Decslred on a Label; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Guide to Creating a Front of Pack (FoP) Nutrition Label for Pre-Packed Products Sold through Retail Outlets; Department of Health and Food Standard Agency: London, UK, 2016.

- Aprobación de Nueva ley de Alimentos en Chile: Resumen del Proceso. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura Organización Panamericana de la Salud Santiago. 2017. Available online: http://www.dinta.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/FAO-Ley-etiquetado-Chile-Resumen-2017.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- EUR-Lex—32011R1169—EN—EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32011R1169 (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- EUR-Lex—32006R1924—EN—EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32006R1924 (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Ruiz, E.; Ávila, J.M.; Valero, T.; del Pozo, S.; Rodriguez, P.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Gil, Á.; González-Gross, M.; Ortega, R.M.; Serra-Majem, L.; et al. Energy intake, profile, and dietary sources in the spanish population: Findings of the anibes study. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4739–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, E.; Rodriguez, P.; Valero, T.; Ávila, J.M.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Gil, Á.; González-Gross, M.; Ortega, R.M.; Serra-Majem, L.; Varela-Moreiras, G. Dietary intake of individual (free and intrinsic) sugars and food sources in the spanish population: Findings from the ANIBES study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azaïs-Braesco, V.; Sluik, D.; Maillot, M.; Kok, F.; Moreno, L.A. A review of total & added sugar intakes and dietary sources in Europe. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moynihan, P. Sugars and dental caries: evidence for setting a recommended threshold for intake. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Morenga, L.; Mallard, S.; Mann, J. Dietary sugars and body weight: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 2012, 346, e7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Morenga, L.A.; Howatson, A.J.; Jones, R.M.; Mann, J. Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of the effects on blood pressure and lipids. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Gregg, E.W.; Flanders, W.D.; Merritt, R.; Hu, F.B. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaboration PLAN for the Improvement of the Composition of Food and Beverages and Other Measures 2020. Spanish Agency for Consumer Affairs, Food Safety and Nutrition; Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Madrid; 2018. Available online: http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/Plan_Colaboracion_INGLES.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- EU Action Plan on Childhood Obesity 2014–2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/childhoodobesity_actionplan_2014_2020_en.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020. World Health OrganizationRegional Office for Europe. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/294474/European-Food-Nutrition-Action-Plan-20152020-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Federici, C.; Detzel, P.; Petracca, F.; Dainelli, L.; Fattore, G. The impact of food reformulation on nutrient intakes and health, a systematic review of modelling studies. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, J.K.C.; Li, Y.; Nickle, M.S.; Haytowitz, D.B.; Roseland, J.; Nguyen, Q.; Khan, M.; Wu, X.; Somanchi, M.; Williams, J.; et al. Comparison of label and laboratory sodium values in popular sodium-contributing foods in the United States. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food Groups to Focus Action on Added Sugar Reduction, According to Annex II of the High Level Group on Nutrition and Physical Activity (HLGNPA) | Selected Groups for this Study (HLGNPA Groups + other Highly Consumed Groups by Spanish Children) |

|---|---|

| Sugar sweetened Beverages | Sugar sweetened beverages |

| Sugar sweetened dairy and dairy imitates | Flavoured milk drinks |

| Drinking yoghurt | |

| Yoghurt | |

| Dairy-based desserts | |

| Cheese | |

| Soy drinks | |

| Breakfast cereals | Breakfast cereals and cereal bars |

| Bread and bread products | Special packaged bread |

| Bakery products (e.g., cakes and cookies) | Baking and pastries |

| Biscuits | |

| Confectionaries | Sweets |

| Chocolates | |

| Other sweets (chewing gum, marshmallow, etc.) | |

| Ready meals (including ready to prepare products like dry soups, dried mashed potatoes, rice mixture) | Ready meals |

| Savoury snacks | Savoury snacks |

| Crisps | |

| Sauces (including ketchup) | Sauces |

| Sugar sweetened desserts, ice cream and topping | Desserts |

| Ice creams | |

| Jam | |

| Confitures | |

| Canned fruits and vegetables | Canned pineapple |

| Other Fruits in syrup | |

| Milk | |

| Fruit juices | |

| Nectars | |

| Meat products |

| All Products (n = 1173) | Products with Nutritional Claims (n = 64) | Products without Nutritional Claims (n = 1109) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | n | Median | (P25–P75) IQR | N | Median | (P25–P75) IQR 2 | n | Median | (P2–P75) IQR |

| Baking and pastries | 61 | 27.3 | (19.8–31.5) 11.7 | 1 | -- | 4.6 | 60 | 27.4 | (19.9–31.7) 11.9 |

| Biscuits | 45 | 24.9 | (20.9–34.0) 13.1 | 2 | -- | (0.3, 0.6) | 43 | 25.3 | (21.0–34.1) 13.1 |

| Breakfast cereals and cereal bars | 107 | 25.8 | (19.3–31.4) 12.1 | 1 | -- | 0.1 | 106 | 25.9 | (19.3–31.4) 12.1 |

| Canned pineapple | 10 | 11.7 | (11.4–12.2) 0.8 | -- | -- | -- | 10 | 11.7 | (11.4–12.2) 0.8 |

| Cheeses | 30 | 4.4 | (2.8–4.9) 2.1 | -- | -- | -- | 30 | 4.4 | (2.8–4.9) 2.1 |

| Chocolate | 92 | 52.0 | (47.3–58.0) 10.7 | 2 | -- | (0.6, 13.5) | 90 | 52.6 | (47.8–58.0) 10.2 |

| Confitures | 30 | 42.5 | (26.3–46.7) 20.4 | 11 | 5.5 | (2.2–35.0) 32.8 | 19 | 46.5 | (42.6–47.0) 4.4 |

| Crisps | 30 | 0.7 | (0.4–0.8) 0.4 | -- | -- | -- | 30 | 0.7 | (0.4–0.8) 0.4 |

| Dairy-based desserts | 65 | 15.9 | (14.1–19.3) 5.2 | -- | -- | -- | 65 | 15.9 | (14.1–19.3) 5.2 |

| Desserts 1 | 29 | 23.2 | (12.7–33.8) 21.1 | 4 | 9.8 | (6.7–23.1) 16.4 | 25 | 26.7 | (15.6–39.1) 23.5 |

| Drinking yoghurt | 10 | 13.1 | (11.6–13.2) 1.6 | 2 | -- | (4.0, 4.7) | 8 | 13.2 | (12.7–13.4) 0.7 |

| Flavoured milk drinks | 20 | 11.3 | (10.4–12.0) 1.6 | 2 | -- | (4.6, 5.8) | 18 | 11.6 | (10.9–12.0) 1.1 |

| Fruit juices | 44 | 10.0 | (9.0–11.0) 2.1 | -- | -- | -- | 44 | 10.0 | (9.0–11.0) 2.1 |

| Ice creams | 45 | 24.2 | (21.0–27.1) 6.1 | -- | -- | -- | 45 | 24.2 | (21.0–27.1) 6.1 |

| Jam | 5 | 51.2 | (43.2–58.8) 15.6 | 1 | -- | 2.9 | 4 | 55.0 | (47.2–59.5) 12.3 |

| Meat products | 90 | 0.7 | (0.1–1.2) 1.1 | -- | -- | -- | 90 | 0.7 | (0.1–1.2) 1.1 |

| Milk | 51 | 4.7 | (4.6–4.8) 0.2 | -- | -- | -- | 51 | 4.7 | (4.6–4.8) 0.2 |

| Nectars | 18 | 9.5 | (4.3–10.7) 6.4 | 7 | 4.2 | (4.1–6.0) 1.9 | 11 | 10.4 | (9.6–11.1) 1.5 |

| Other Fruits in syrup | 20 | 14.3 | (13.7–16.4) 2.7 | 3 | 5.3 | (5.2–5.8) 0.6 | 17 | 15.6 | (14.0–16.7) 2.7 |

| Other sweets | 27 | 49.4 | (0.1–66.9) 66.8 | 10 | 0.1 | (0.1–0.1) 0.0 | 17 | 61.6 | (54.8–67.1) 12.3 |

| Ready meals | 55 | 2.1 | (1.0–3.2) 2.2 | -- | -- | -- | 55 | 2.1 | (1.0–3.2) 2.2 |

| Sauces | 63 | 6.4 | (2.4–17.0) 14.6 | 4 | 3.7 | (2.5–7.6) 5.1 | 59 | 6.4 | (2.4–18.9) 16.5 |

| Savoury snacks | 45 | 1.2 | (0.4–2.8) 2.4 | -- | -- | -- | 45 | 1.2 | (0.4–2.8) 2.4 |

| Soy drinks | 5 | 2.1 | (1.0–2.7) 1.7 | -- | -- | -- | 5 | 2.1 | (1.0–2.7) 1.7 |

| Special packaged bread | 45 | 4.4 | (3.9–5.1) 1.2 | -- | -- | -- | 45 | 4.4 | (3.9–5.1) 1.2 |

| Sugar Sweetened Beverages | 47 | 7.2 | (4.7–10.1) 5.4 | 4 | 4.6 | (4.0–5.8) 1.9 | 43 | 7.6 | (6.0–10.2) 4.2 |

| Sweets | 34 | 70.2 | (62.8–76.1) 13.3 | 5 | 0.1 | (0.1–0.1) 0.0 | 29 | 71.4 | (66.3–81.7) 15.4 |

| Yoghurt | 50 | 12.3 | (5.8–13.5) 7.7 | 5 | 4.9 | (4.9–5.2) 0.3 | 45 | 12.6 | (10.5–13.6) 3.1 |

| Total | 1173 | 11.6 | (3.7–26.9) 23.2 | 64 | 4.2 | (0.2–5.8) 5.6 | 1109 | 12.2 | (4.0–28.1) 24.1 |

| Meets n (%) | Does not Meet (n (%)) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Label Value (LV) >Analytical Vvalue (AV) | Label value (LV) <Analytical value (AV) | ||

| Baking and pastries | 60 | 59 (98.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) |

| Biscuits | 43 | 43 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Breakfast cereals and cereal bars | 106 | 102 (96.2) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Canned pineapple | 10 | 10 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cheese | 30 | 29 (96.7) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) |

| Chocolate | 88 | 88 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Confitures | 19 | 19 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Crisps | 27 | 27 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Dairy-based desserts | 65 | 64 (98.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Desserts | 24 | 23 (95.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) |

| Drinking yoghurt | 8 | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Flavoured milk drinks | 18 | 18 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Fruit juices | 44 | 44 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ice creams | 45 | 45 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Jam | 4 | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Meat products | 79 | 78 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Milk | 51 | 51 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Nectars | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other fruits in syrup | 16 | 16 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other sweets | 13 | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ready meals | 51 | 51 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sauces | 58 | 57 (98.3) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) |

| Savoury snacks | 42 | 39 (92.9) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0) |

| Soy drinks | 5 | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Special packaged bread | 45 | 44 (97.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) |

| Sugar Sweetened Beverages | 43 | 41 (95.3) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0) |

| Sweets | 24 | 24 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Yoghurt | 45 | 45 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 1074 | 1057 (98.4) | 12 (1.1) | 5 (0.5) |

| Groups | Product | LV (g/100g) | AV (g/100g) | LV-AV (g/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baking and pastries | Children’s industrial bakery | 20 | 38.6 | −18.6 |

| Breakfast cereals and cereal bars | Breakfast cereals with honey | 49 | 35 | 14 |

| Cereal bars | 36 | 21 | 15 | |

| Integral breakfast cereals with fruit | 23 | 30.5 | −7.5 | |

| Muesli | 20.2 | 12.9 | 7.3 | |

| Cheeses | Spread and melted cheeses | 7 | 4.7 | 2.3 |

| Dairy-based desserts | Custard | 4.5 | 15.2 | −10.7 |

| Desserts | Chocolate cake | 15.2 | 21.9 | −6.7 |

| Meat products | Chopped | 3.5 | 0.8 | 2.7 |

| Nectars | Nectar | 14.4 | 10 | 4.4 |

| Sauces | Mustard | 5.9 | 3.5 | 2.4 |

| Savoury snacks | Microwave popcorn 1 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 3.4 |

| Microwave popcorn 2 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 3 | |

| Microwave popcorn 3 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 3 | |

| Special packaged bread | Integral tin loaf bread | 3 | 6.2 | −3.2 |

| Sugar Sweetened Beverages | Sugar sweetened beverage 1 | 6.3 | 4.1 | 2.2 |

| Sugar sweetened beverage 2 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 2.1 |

| Groups | Subcategories | n | Label Value (LV) (g/100 g) | Analytical Value (AV) (g/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (P25–P75) | Median (P25–P75) | |||

| Baking and pastries | Industrial croissants and similar | 11 | 12.0 (12.0–13.0) | 12.4 (12.1–13.0) |

| Industrial pastries for children | 21 | 32.0 (24.6–39.0) | 32.0 (26.5–38.0) | |

| Muffins | 15 | 29.0 (26.4–30.0) | 29.1 (26.9–31.3) | |

| Other (donuts, etc.) | 13 | 24.4 (19.0–30.0) | 24.4 (19.8–29.9) | |

| Total | 60 | 26.7 (19.5–31.0) | 27.4 (19.9–31.7) | |

| Biscuits | Filled biscuits | 18 | 37.0 (32.0–41.0) | 37.3 (33.1–40.7) |

| Sweet biscuit | 21 | 22.0 (21.0–24.0) | 23.6 (20.9–24.6) | |

| Other unfilled biscuits (digestives, cookies, etc.) | 4 | 18.0 (17.2–18.0) | 18.0 (17.2–18.2) | |

| Total | 43 | 25.0 (21.0–34.0) | 25.3 (21.0–34.1) | |

| Breakfast cereals and cereal bars | Breakfast Cereals with honey | 16 | 30.5 (26.7–36.0) | 31.0 (27.5–35.1) |

| Cereal bars | 16 | 30.7 (28.0–36.0) | 30.4 (27.5–34.5) | |

| Chocolate filled Breakfast Cereals | 6 | 33.3 (29.0–36.0) | 34.3 (29.4–36.8) | |

| Chocolate flavoured Breakfast Cereals | 14 | 28.9 (28.0–34.0) | 29.7 (28.7–34.0) | |

| Cornflakes cereals | 14 | 7.0 (5.0–8.0) | 7.1 (4.9–8.0) | |

| Muesli | 16 | 22.2 (20.2–25.7) | 22.4 (18.9–24.3) | |

| Sugared breakfast cereals | 12 | 25.0 (24.1–30.5) | 24.4 (23.4–30.0) | |

| Other breakfast cereals | 12 | 19.0 (2.8–23.5) | 18.8 (2.8–23.5) | |

| Total | 106 | 25.4 (20.2–31.0) | 25.9 (19.3–31.4) | |

| Canned pineapple | Canned pineapple | 10 | 12.0 (11.6–12.0) | 11.7 (11.4–12.2) |

| Total | ||||

| Cheeses | Spread and melted cheeses | 30 | 4.3 (3.0–5.2) | 4.4 (2.8–4.9) |

| Total | ||||

| Chocolates | Chocolate bars | 15 | 49.5 (44.0–51.1) | 48.9 (46.3–51.7) |

| Chocolate eggs and similar | 5 | 57.7 (57.6–58.0) | 58.0 (56.9–58.2) | |

| Chocolate large bars (dark, with milk, white) | 31 | 53.8 (46.0–55.9) | 54.0 (46.3–56.1) | |

| Chocolate like bean (carob) and similar | 5 | 53.8 (43.7–64.1) | 53.5 (44.4–62.4) | |

| Chocolate spreads | 5 | 58.0 (57.0–59.0) | 58.0 (56.8–58.1) | |

| Chocolates | 20 | 49.6 (47.1–51.9) | 50.3 (46.7–51.8) | |

| Cocoa powder | 7 | 70.0 (67.0–75.7) | 69.9 (68.1–75.4) | |

| Total | 88 | 52.1 (47.9–57.7) | 52.0 (47.7–58.0) | |

| Confitures | Confitures | 19 | 46.9 (43.2–47.0) | 46.5 (42.6–47.0) |

| Total | ||||

| Crisps | Crisps | 27 | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.7 (0.4–0.8) |

| Total | ||||

| Dairy-based desserts | Custard | 15 | 16.0 (15.0–16.8) | 15.9 (15.0–16.6) |

| Flan | 15 | 20.8 (16.0–24.3) | 19.7 (15.9–23.3) | |

| Flavoured fromage frais | 13 | 13.4 (13.0–14.0) | 13.1 (12.3–13.8) | |

| Others (chocolate cups, mousse, etc.) | 22 | 17.4 (16.0–20.0) | 17.4 (15.0–19.9) | |

| Total | 65 | 16.3 (14.9–20.0) | 15.9 (14.1–19.3) | |

| Desserts | Non-dairy desserts | 16 | 19.6 (14.4–35.0) | 21.0 (14.3–36.0) |

| Powder for dessert preparation 1 | 8 | 29.0 (13.3–70.4) | 28.9 (13.6–69.9) | |

| Total | 24 | 26.7 (14.4–39.0) | 26.9 (14.3–39.6) | |

| Drinking yoghurt | Drinking yoghurt | 8 | 13.2 (12.7–13.8) | 13.2 (12.7–13.4) |

| Total | ||||

| Flavoured milk drinks | Flavoured milk drinks | 18 | 12.0 (11.0–12.0) | 11.6 (10.9–12.0) |

| Total | ||||

| Fruit juices | Fruit juices | 44 | 10.0 (9.2–11.0) | 10.0 (9.0–11.0) |

| Total | ||||

| Ice creams | Ice cream to share (bars, frozen cakes, etc.) | 25 | 24.0 (22.6–26.0) | 23.8 (21.0–26.2) |

| Individual ice cream | 20 | 25.4 (21.5–29.0) | 25.0 (21.1–28.4) | |

| Total | 45 | 24.0 (22.0–27.0) | 24.2 (21.0–27.1) | |

| Jam | Jam | 4 | 55.5 (47.4–59.5) | 55.0 (47.2–59.5) |

| Total | ||||

| Meat products | Chopped | 9 | 1.0 (0.5–2.5) | 0.8 (0.1–0.9) |

| Cooked ham | 10 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.4) | |

| Cured ham | 15 | 0.4 (0.1–0.5) | 0.1 (0.1–0.4)* | |

| Cured sausage (chorizo) | 9 | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) | 0.4 (0.1–1.0) | |

| Cured sausage (salchichon) | 9 | 3.0 (1.6–3.5) | 3.0 (1.7–3.8) | |

| Sausages | 18 | 1.0 (0.5–1.0) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | |

| Turkey | 9 | 1.0 (0.4–2.0) | 0.5 (0.1–1.5) | |

| Total | 79 | 1.0 (0.5–1.6) | 0.7 (0.1–1.3)* | |

| Milk | Whole milk | 15 | 4.6 (4.6–4.7) | 4.7 (4.6–4.8) |

| Semi-skimmed milk | 15 | 4.7 (4.7–4.8) | 4.7 (4.6–4.7) | |

| Skimmed milk | 15 | 4.8 (4.7–4.8) | 4.7 (4.7–4.8) | |

| Lactose free milk | 6 | 4.8 (4.7–4.8) | 4.7 (4.6–4.8) | |

| Total | 51 | 4.7 (4.7–4.8) | 4.7 (4.6–4.8) | |

| Nectar | Nectar | 11 | 10.4 (10.0–11.6) | 10.4 (9.6–11.1) |

| Total | ||||

| Other fruits in syrup | Peach | 8 | 16.2 (14.0–17.0) | 15.9 (13.9–17.1) |

| Pineapple | 3 | 15.0 (14.0–16.4) | 14.2 (14.1–16.7) | |

| Other fruits | 5 | 14.0 (14.0–16.0) | 14.3 (13.8–15.6) | |

| Total | 16 | 15.5 (14.0–16.4) | 15.0 (13.9–16.4) | |

| Other sweets | Other sweets 2 | 13 | 62.0 (59.0–67.8) | 62.0 (59.3–67.5) |

| Total | ||||

| Ready meals | Lasagna /cannelloni | 11 | 2.7 (1.2–3.4) | 2.7 (1.0–3.4) |

| Pizza | 20 | 2.4 (1.7–3.5) | 2.7 (1.7–3.4) | |

| Others | 20 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.9 (0.8–2.8) | |

| Total | 51 | 2.4 (1.2–3.1) | 2.3 (1.3–3.3) | |

| Sauces | Ketchup | 14 | 21.4 (19.3–22.8) | 20.8 (19.1–22.8) |

| Mayonnaise | 14 | 1.6 (1.4–3.0) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | |

| Tomato sauce | 13 | 7.4 (6.7–8.1) | 7.2 (7.1–7.8) | |

| Other sauces | 17 | 3.0 (2.6–5.9) | 3.2 (2.6–4.9) | |

| Total | 58 | 6.5 (2.6–17.0) | 6.4 (2.4–17.0) | |

| Savoury snacks | Corn snacks | 15 | 2.2 (1.0–4.1) | 2.1 (0.8–4.2) |

| Microwave popcorn | 8 | 1.1 (0.4–3.6) | 0.4 (0.4–0.9) | |

| Other savoury snacks 3 | 19 | 1.8 (0.7–5.1) | 1.9 (0.1–4.9) | |

| Total | 42 | 2.1 (0.8–3.8) | 1.4 (0.4–3.7) | |

| Soy drinks | Soy drinks | 5 | 2.1 (0.7–2.8) | 2.1 (1.0–2.7) |

| Total | ||||

| Special packaged bread | White tin loaf bread | 14 | 3.2 (2.9–4.0) | 4.0 (3.5–4.5) |

| Integral tin loaf bread | 16 | 3.0 (2.7–4.2) | 4.2 (3.4–4.8) | |

| Toasted bread | 15 | 5.1 (4.3–5.6) | 5.5 (4.4–5.9) | |

| Total | 45 | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.4 (3.9–5.1) | |

| Sugar sweetened beverages | Beverages with fruits | 3 | 11.0 (4.6–11.9) | 10.8 (4.6–11.9) |

| Sugar Sweetened beverages | 40 | 7.5 (6.3–10.2) | 7.5 (6.1–10.1) | |

| Total | 43 | 7.7 (6.3–10.5) | 7.6 (6.0–10.2) | |

| Sweets | Sweets | 24 | 72.0 (68.8–81.8) | 71.9 (67.2–81.9) |

| Total | ||||

| Yoghurt | Plain yoghurt | 9 | 4.0 (4.0–4.3) | 4.0 (3.9–4.8) |

| Flavoured yoghurt | 18 | 12.8 (11.0–14.0) | 12.8 (11.4–13.5) | |

| Fruit Yoghurt | 12 | 14.1 (12.8–15.0) | 14.3 (12.8–15.1) | |

| Sugar sweetened yoghurt | 6 | 12.5 (12.3–13.3) | 12.4 (12.2–13.4) | |

| Total | 45 | 12.5 (10.1–14.0) | 12.6 (10.5–13.6) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yusta-Boyo, M.J.; Bermejo, L.M.; García-Solano, M.; López-Sobaler, A.M.; Ortega, R.M.; García-Pérez, M.; Dal-Re Saavedra, M.Á.; on behalf of the SUCOPROFS Study Researchers. Sugar Content in Processed Foods in Spain and a Comparison of Mandatory Nutrition Labelling and Laboratory Values. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041078

Yusta-Boyo MJ, Bermejo LM, García-Solano M, López-Sobaler AM, Ortega RM, García-Pérez M, Dal-Re Saavedra MÁ, on behalf of the SUCOPROFS Study Researchers. Sugar Content in Processed Foods in Spain and a Comparison of Mandatory Nutrition Labelling and Laboratory Values. Nutrients. 2020; 12(4):1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041078

Chicago/Turabian StyleYusta-Boyo, María José, Laura M. Bermejo, Marta García-Solano, Ana M. López-Sobaler, Rosa M. Ortega, Marta García-Pérez, María Ángeles Dal-Re Saavedra, and on behalf of the SUCOPROFS Study Researchers. 2020. "Sugar Content in Processed Foods in Spain and a Comparison of Mandatory Nutrition Labelling and Laboratory Values" Nutrients 12, no. 4: 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041078

APA StyleYusta-Boyo, M. J., Bermejo, L. M., García-Solano, M., López-Sobaler, A. M., Ortega, R. M., García-Pérez, M., Dal-Re Saavedra, M. Á., & on behalf of the SUCOPROFS Study Researchers. (2020). Sugar Content in Processed Foods in Spain and a Comparison of Mandatory Nutrition Labelling and Laboratory Values. Nutrients, 12(4), 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041078