Maternal Diets in India: Gaps, Barriers, and Opportunities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review of Dietary Data from National Surveys

2.2. Empirical Analysis of Publicly Available Data

2.3. Literature Review

3. Results

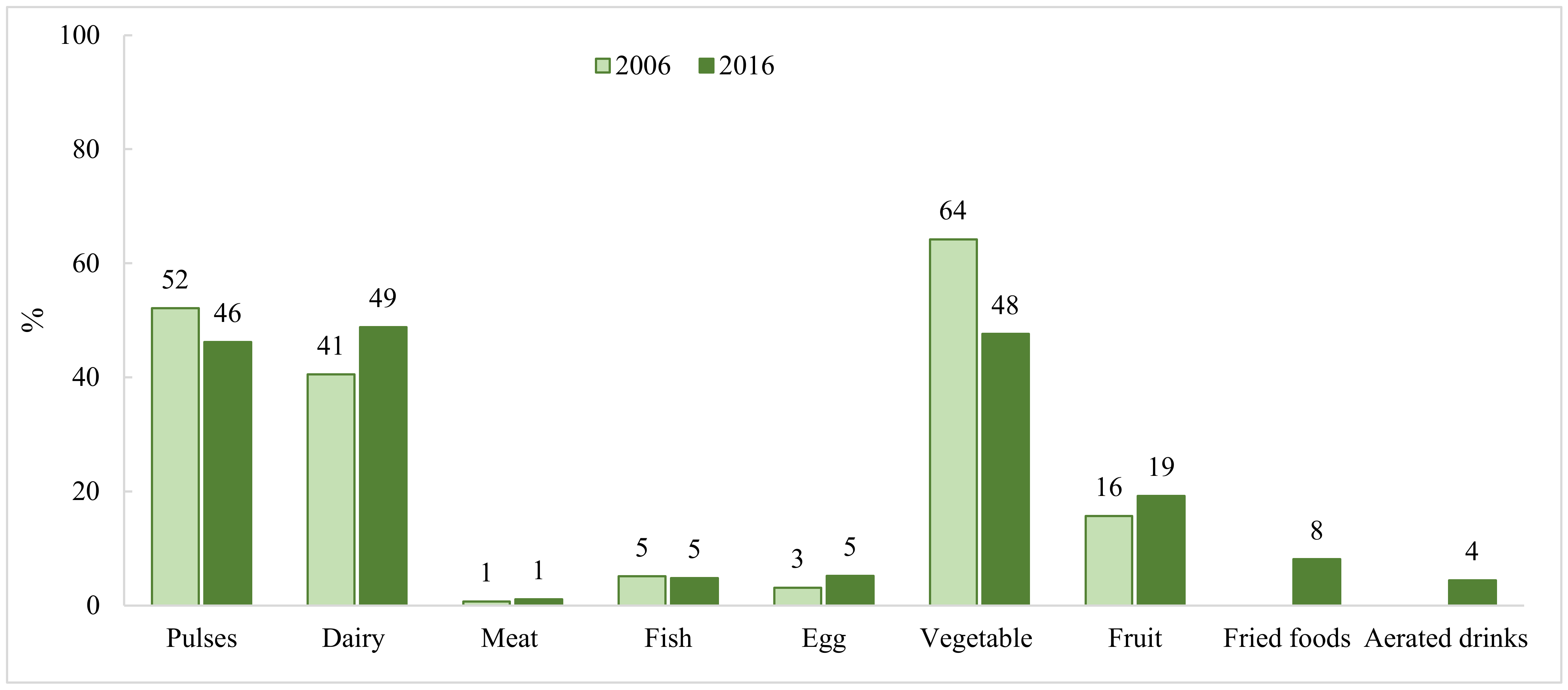

3.1. Current Situation of Maternal Diets in India

3.1.1. Maternal Diets at the National Level

3.1.2. Maternal Diets at the Subnational Level

3.2. Enablers of and Barriers to Adopting Recommended Diets in India

3.2.1. Food Availability and Accessibility

3.2.2. Economic Constraint and Affordability

3.2.3. Exposure to Health and Nutrition Services

3.2.4. Maternal Education

3.2.5. Maternal Knowledge

3.2.6. Food Taboos and Restrictions during Pregnancy

3.2.7. Family Influence

3.2.8. Gender Norms

3.2.9. Other Demographic Factors

3.2.10. Indigenous Foods

3.3. Policies to Improve Maternal Diet

3.4. Current Intervention Strategies in India to Improve Dietary Intakes and Their Effectiveness

3.4.1. Hot Cooked Meals

3.4.2. Food Innovations in Take-Home Rations

3.4.3. Maternal Cash Transfers

3.4.4. Food Fortification of Staples

3.4.5. Behavior Change Communication

3.4.6. Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Interventions: Empowerment through Income and Access to Nutritious Foods

4. Discussion

4.1. Data Gaps on Maternal Dietary Practices and Evaluation Impacts of Programs and Interventions

4.2. Factors Influencing Maternal Diets in India

4.3. Intervention Strategies with Potential to Improve Maternal Diets in India

4.4. Policy Implication

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Victora, C.G.; Christian, P.; Vidaletti, L.P.; Gatica-Dominguez, G.; Menon, P.; Black, R.E. Revisiting maternal and child undernutrition in low-income and middle-income countries: Variable progress towards an unfinished agenda. Lancet 2021, 397, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, U.; Grant, F.; Goldenberg, T.; Zongrone, A.; Martorell, R. Effect of women’s nutrition before and during early pregnancy on maternal and infant outcomes: A systematic review. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26 (Suppl. 1), 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Health Observatory. Data on Anemia. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/anaemia_in_women_and_children (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet 2020, 395, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barker, D.J.P. Mothers, Babies and Health in Later Life; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.E.; Talegawkar, S.A.; Merialdi, M.; Caulfield, L.E. Dietary intakes of women during pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1340–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lander, R.L.; Hambidge, K.M.; Westcott, J.E.; Tejeda, G.; Diba, T.S.; Mastiholi, S.C.; Khan, U.S.; Garces, A.; Figueroa, L.; Tshefu, A.; et al. Pregnant women in four low-middle income countries have a high prevalence of inadequate dietary intakes that are improved by dietary diversity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Scott, S.; Avula, R.; Tran, L.M.; Menon, P. Trends and drivers of change in the prevalence of anaemia among 1 million women and children in India, 2006 to 2016. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e001010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, M.F.; Nguyen, P.; Tran, L.M.; Avula, R.; Menon, P. A double edged sword? Improvements in economic conditions over a decade in India led to declines in undernutrition as well as increases in overweight among adolescents and women. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, B.; Agrawal, S.; Beaudreault, A.R.; Avula, L.; Martorell, R.; Osendarp, S.; Prabhakaran, D.; McLean, M.S. Dietary and nutritional change in India: Implications for strategies, policies, and interventions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1395, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramakrishnan, U.; Lowe, A.; Vir, S.; Kumar, S.; Mohanraj, R.; Chaturvedi, A.; Noznesky, E.A.; Martorell, R.; Mason, J.B. Public health interventions, barriers, and opportunities for improving maternal nutrition in India. Food Nutr. Bull. 2012, 33, S71–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abhiyaan, P. PM’s Overarching Scheme for Holistic Nourishment. Available online: http://poshanabhiyaan.gov.in/#/ (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau. Diet and Nutritional Status of Rural Population, Prevalence of Hypertension & Diabetes Among Adults and Infant & Young Child Feeding Practices—Report of Third Repeat Survey; NNMB Technical Report No 26; National Institute of Nutrition; Indian Council of Medical Research: Hyderabad, India, 2012.

- IIPS—International Institute for Population Sciences and Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06; IIPS: Mumbai, India, 2007; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- IIPS—International Institute for Population Sciences and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16; IIPS: Mumbai, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ICMR-National Institute of Nutrition. Recommended Dietary Allowances and Estimated Average Requirements Nutrient Requirements for Indians-2020: A Report of the Expert Group Indian Council of Medical Research National Institute of Nutrition; National Institute of Nutrition: Hyderabad, India, 2020.

- Otten, J.; Hellwig, J.; Meyers, L. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Torheim, L.E.; Ferguson, E.L.; Penrose, K.; Arimond, M. Women in resource-poor settings are at risk of inadequate intakes of multiple micronutrients. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 2051S–2058S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Kachwaha, S.; Avula, R.; Young, M.; Tran, L.M.; Ghosh, S.; Agrawal, R.; Escobar-Alegria, J.; Patil, S.; Menon, P. Maternal nutrition practices in Uttar Pradesh, India: Role of key influential demand and supply factors. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unisa, S.; Saraswat, A.; Bhanot, A.; Jaleel, A.; Parhi, R.N.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Purty, A.; Rath, S.; Mohapatra, B.; Lumba, A.; et al. Predictors of the diets consumed by adolescent girls, pregnant women and mothers with children under age two years in rural eastern India. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2020, 53, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alive & Thrive. Nutrition Practices in Uttar Pradesh, Results of a Formative Research Study; Alive & Thrive: Uttar Pradesh, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, L.T.; Thilsted, S.H.; Nielsen, B.B.; Rangasamy, S. Food and nutrient intakes among pregnant women in rural Tamil Nadu, South India. Public Health Nutr. 2003, 6, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Catherin, N.; Rock, B.; Roger, V.; Anlita, C.; Ashish, G.; Delwin, P.; Shanbhag, D.; Goud, B. Beliefs and practices regarding nutrition during pregnancy and lactation in a rural area in Karnataka, India: A qualitative study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2015, 2, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Chakrabarti, A. Food taboos in pregnancy and early lactation among women living in a rural area of West Bengal. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Raghunathan, K.; Alderman, H.; Menon, P.; Nguyen, P. India’s Integrated Child Development Services programme; equity and extent of coverage in 2006 and 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H.C.; Jeyanthi, R.; Pelto, G.; Willford, A.C.; Stoltzfus, R.J. Using a cultural-ecological framework to explore dietary beliefs and practices during pregnancy and lactation among women in Adivasi communities in the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve, India. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2018, 57, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganpule-Rao, A.V.; Roy, D.; Karandikar, B.A.; Yajnik, C.S.; Rush, E.C. Food Access and Nutritional Status of Rural Adolescents in India: Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 58, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, N.R. In-Depth Understanding of Drivers of Maternal Nutrition Behavior Change in the Context of an Ongoing Maternal Nutrition Intervention in Uttar Pradesh, India. Master’s Thesis, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/n296x0341?locale=en (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Kachwaha, S.; Nguyen, P.H.; DeFreese, M.; Avula, R.; Cyriac, S.; Girard, A.; Menon, P. Assessing the Economic Feasibility of Assuring Nutritionally Adequate Diets for Vulnerable Populations in Uttar Pradesh, India: Findings from a “Cost of the Diet” Analysis. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, S.H.; Dhurde, V.; Bhaise, S.; Kale, R.; Kumaran, K.; Gelli, A.; Rengalakshmi, R.; Lawrence, W.; Bloom, I.; Sahariah, S.A.; et al. Barriers and facilitators to fruit and vegetable consumption among rural indian women of reproductive age. Food Nutr. Bull. 2019, 40, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lakshmi, G. Food preferences and taboos during ante-natal period among the tribal women of north coastal Andhra Pradesh. J. Community Nutr. Health 2013, 2, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sarkar, A. Pregnancy-related food habits among women of rural Sikkim, India. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raghunathan, K.; Headey, D.; Herforth, A. Affordability of nutritious diets in rural India. Food Policy 2021, 99, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammohan, A.; Goli, S.; Singh, D.; Ganguly, D.; Singh, U. Maternal dietary diversity and odds of low birth weight: Empirical findings from India. Women Health 2019, 59, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ROSHNI—ROSHNI-Centre of Women Collectives Led Social Action. Formative Research on Engaging Men & Boys for Advancing Gender Equality in the Swabhimaan Programme; Lady Irwin College: New Delhi, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sadhu, G.; Prusty, R.K.; Rani, V.; Nigam, S.; Bandhu, A.; Dhakad, R.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, V.K.; Sharif Gautam, S. A Study Report on “Formulation of Evidence-Based and Actionable Dietary Advice for Pregnant and Lactating Women in Rajasthan”; Institute of Health and Management Research: Rajasthan, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A.; Sabharwal, V.; Qualitz, G.; Bader, N. Influence of Social Inequalities on Dietary Diversity and Household Food Insecurity: An In-Depth Nutrition Baseline Survey Conducted in Madhya Pradesh, India. World Rev. Nutr. Diet 2020, 121, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Akhtar, F.; Kumar Singh, R.; Mehra, S. Dietary patterns and determinants of pregnant and lactating women from marginalized communities in india: A community-based cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 595170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OneWorld Foundation India; UNICEF. Forest Lanterns; Penguin Random House India Pvt. Ltd.: Haryana, India, 2017; Available online: https://oneworld.net.in/wp-content/uploads/forest-lanterns.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Stephens, C. Nutrition, Biodiversity and Traditional Knowledge. The Malnoursihed Tribal. A Symposium on the Continuing Burden of Hunger and Illness in Our Tribal Communities. 2014. Available online: https://www.india-seminar.com/2014/661/661_carolyn_stephens.htm (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Sarangi, D.; Trustee, M.; Patra, P. Forests as a Food Producing Habitat. Nourishing Tribals. A Symposium on Nutrition Sensitive Practices in Schedule V States of India. 2016. Available online: https://www.india-seminar.com/2016/681/681_debjeet_sarangi_et_al.htm (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- ICMR; NIN; Abhiyaan, P. Area-Wise Diet Charts Developed for Pregnant Women and Malnourished Pregnant Women in Reproductive Age. 2020. Available online: https://wcd.nic.in/acts/area-wise-diet-charts-developed-pregnant-women-and-malnourished-pregnant-women-reproductive-age (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Sethi, V.; Tiwari, K.; Sareen, N.; Singh, S.; Mishra, C.; Jagadeeshwar, M.; Sunitha, K.; Kumar, S.V.; de Wagt, A.; Sachdev, H.P.S. Delivering an Integrated Package of Maternal Nutrition Services in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (India). Food Nutr. Bull. 2019, 40, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Nutrition. Assessment of Effect of ‘Anna Amrutha Hastham’ on Nutritional Status of Pregnant Women and Lactating Mothers in the State of Andhra Pradesh; Indian Council of Medical Research: Hyderabad, India, 2016.

- Babu, G.R.; Shapeti, S.S.; Saldanha, N.; Deepa, R.; Prafully, S.; Yamuna, A. Evaluating the Effect of One Full Meal a Day in Pregnant and Lactating Women (FEEL): A Prospective Study; Indian Institute of Public Health; Public Health Foundation of India: Bangaluru, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Tiwari, S.K. Probiotic Potential of Lactobacillus plantarum LD1 Isolated from Batter of Dosa, a South Indian Fermented Food. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2014, 6, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunathan, K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Avula, R.; Kim, S.S. Can conditional cash transfers improve the uptake of nutrition interventions and household food security? Evidence from Odisha’s Mamata scheme. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, G.J.; Sodani, P.R.; Sankar, R.; Fairhurst, J.; Siling, K.; Guevarra, E.; Norris, A.; Myatt, M. Household coverage of fortified staple food commodities in Rajasthan, India. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Kishore, A.; Raghunathan, K.; Scott, S.P. Impact of subsidized fortified wheat on anaemia in pregnant Indian women. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collison, D.K.; Kekre, P.; Verma, P.; Melgen, S.; Kram, N.; Colton, J.; Blount, W.; Girard, A.W. Acceptability and utility of an innovative feeding toolkit to improve maternal and child dietary practices in Bihar, India. Food Nutr. Bull. 2015, 36, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Kashyap, S. Effect of counseling on nutritional status during pregnancy. Indian J. Pediatr. 2006, 73, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Kachwaha, S.; Tran, L.M.; Avula, R.; Young, M.F.; Ghosh, S.; Sharma, P.K.; Escobar-Alegria, J.; Forissier, T.; Patil, S.; et al. Strengthening nutrition interventions in antenatal care services affects dietary intake, micronutrient intake, gestational weight gain, and breastfeeding in Uttar Pradesh, India: Results of a cluster-randomized program evaluation. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2282–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivalli, S.; Srivastava, R.K.; Singh, G.P. Trials of improved practices (TIPs) to enhance the dietary and iron-folate intake during pregnancy—A quasi experimental study among rural pregnant women of Varanasi, India. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Daivadanam, M.; Wahlstrom, R.; Ravindran, T.K.S.; Sarma, P.S.; Sivasankaran, S.; Thankappan, K.R. Changing household dietary behaviours through community-based networks: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial in rural Kerala, India. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, V.; Kumar, P.; Wagt, A.D. Development of a maternal service package for mothers of children with severe acute malnutrition admitted to nutrition rehabilitation centres in India. Field Exch. 2019, 59, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Beesabathuni, K.; Lingala, S.; Kumari, P. How Eggs and Women Transformed a Malnutrition-Prone Village. 2021. Available online: https://poshan.outlookindia.com/story/poshan-news-how-eggs-transformed-women-and-a-malnutrition-prone-tribal-village/375087 (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Kadiyala, S.; Harris-Fry, H.; Pradhan, R.; Mohanty, S.; Padhan, S.; Rath, S.; James, P.; Fivian, E.; Koniz-Booher, P.; Nair, N.; et al. Effect of nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions with participatory videos and women’s group meetings on maternal and child nutritional outcomes in rural Odisha, India (UPAVAN trial): A four-arm, observer-blind, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5, e263–e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, D.; Biebinger, R.; Bruins, M.J.; Hoeft, B.; Kraemer, K. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, folic acid, and vitamin A from fortified maize. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1312, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO; FAO. Guidelines on Food Fortification with Micronutrients; World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Choedon, T.; Dinachandra, K.; Sethi, V.; Kumar, P. Screening and management of maternal malnutrition in nutritional rehabilitation centers as a routine service: A feasibility study in kalawati saran children hospital, New Delhi. Indian J. Community Med. 2021, 46, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Development Initiatives. Global Nutrition Report 2017: Nourishing the SDGs; Development Initiatives: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau. Diet and Nutritional Status of Urban Population in India and Prevalence of Obesity, Hypertension, Diabetes Among Hyperlipidemia in Urban Men and Women. A Brief Report NNMB Urban Nutrition Report; NNMB Technical Report No 27; National Institute of Nutrition; Indian Council of Medical Research: Hyderabad, India, 2017.

- National Institute of Nutrition. Dietary Guidelines for Indians: A Manual; National Institute of Nutrition: Hyderabad, India, 2011.

- Kachwaha, S.R.; Avula, P.; Menon, V.; Sethi, W.; Joe, W.; Laxmaiah, A. Improving Maternal Nutrition in India Through Integrated Hot-Cooked Meal Programs: A Review of Implementation Evidence; International Food Policy Research Institute: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Fry, H.A.; Paudel, P.; Harrisson, T.; Shrestha, N.; Jha, S.; Beard, B.J.; Copas, A.; Shrestha, B.P.; Manandhar, D.S.; Costello, A.M.L.; et al. Participatory women’s groups with cash transfers can increase dietary diversity and micronutrient adequacy during pregnancy, whereas women’s groups with food transfers can increase equity in intrahousehold energy allocation. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olney, D.K.; Talukder, A.; Iannotti, L.L.; Ruel, M.T.; Quinn, V. Assessing impact and impact pathways of a homestead food production program on household and child nutrition in Cambodia. Food Nutr. Bull. 2009, 30, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Kim, S.S.; Sanghvi, T.; Mahmud, Z.; Tran, L.M.; Shabnam, S.; Aktar, B.; Haque, R.; Afsana, K.; Frongillo, E.A.; et al. Integrating nutrition interventions into an existing maternal, neonatal, and child health program increased maternal dietary diversity, micronutrient intake, and exclusive breastfeeding practices in Bangladesh: Results of a cluster-randomized program evaluation. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 2326–2337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chilton, S.N.; Burton, J.P.; Reid, G. Inclusion of fermented foods in food guides around the world. Nutrients 2015, 7, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamang, J.P. History and culture of indian ethnic fermented foods and beverages. In Ethnic Fermented Foods and Beverages of India: Science History and Culture; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

| NNMB Survey 1 (n = 322) | Uttar Pradesh 2 (n = 667) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Intake per Day | Inadequate Intake 3 | Average Intake per Day | Inadequate Intake 4 | |||

| Median | Mean (SD) | % | Median | Mean (SD) | % | |

| Macronutrients | ||||||

| Energy intake (kcal) | 1736 | 1773 (604) | 13.7 | 1647 | 1759 (743) | NA |

| Protein intake (g) | 44.5 | 48.6 (21.5) | 35.7 | 55.8 | 59.4 (28.3) | 10.9 |

| Fat (g) | 23.5 | 28.1 (17.5) | 19.6 | 19.7 | 25.3 (19.8) | 88.2 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | NA | NA | NA | 349 | 379 (163) | 0.8 |

| Micronutrients | ||||||

| Calcium (g) | 334 | 418 (321) | 76.1 | 227 | 335.5 (296.4) | 89.6 |

| Iron (mg) | 11.3 | 13.7 (9.3) | 78.0 | 5.2 | 6.8 (5.5) | 94.6 |

| Zinc (mg) | NA | NA | NA | 4.2 | 5.1 (3.5) | 87.8 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 28.0 | 43.0 (48.0) | 50.6 | 35.1 | 52.7 (71.6) | 82.0 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 1.1 | 1.3 (0.7) | 16.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 (0.6) | 45.4 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.7 | 0.8 (0.3) | 52.5 | 0.74 | 0.9 (0.7) | 80.5 |

| Niacin—Vitamin B3 (mg) | 12.9 | 13.8 (6.3) | 13.4 | 12.2 | 13.1 (6.1) | 59.8 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | NA | NA | NA | 0.6 | 0.7 (0.4) | 94.3 |

| Folate total (µg) | 109.0 | 129.0 (84.5) | 72.0 | 104 | 128.8 (99.1) | 96.9 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | NA | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0 (0.1) | 98.2 |

| Vitamin A (RAE) (µg) | 124 | 291 (480) | 83.2 | 9.0 | 27.6 (51.6) | 98.2 |

| Pulses | Dairy | Meat/Fish/Eggs | Fruits | Dark Green Leafy Vegetables | Unhealthy Foods | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Socioeconomic status (ref: poorest) | ||||||

| Poor | 1.10 (1.00, 1.20) | 1.34 *** (1.22, 1.48) | 1.32 * (1.04, 1.68) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.10) | 1.65 *** (1.36, 2.00) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.15) |

| Middle | 1.07 (0.97, 1.18) | 1.71 *** (1.54, 1.90) | 1.91 *** (1.50, 2.43) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.18) | 2.12 *** (1.77, 2.55) | 0.91 (0.80, 1.04) |

| Rich | 1.08 (0.98, 1.20) | 2.43 *** (2.19, 2.70) | 1.72 *** (1.33, 2.22) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.09) | 2.84 *** (2.36, 3.42) | 0.82 ** (0.72, 0.93) |

| Very rich | 1.10 (0.99, 1.23) | 3.71 *** (3.31, 4.15) | 1.84 *** (1.43, 2.38) | 1.05 (0.94, 1.17) | 5.01 *** (4.17, 6.02) | 0.73 *** (0.64, 0.84) |

| Household size (ref: ≤4) | ||||||

| 5–6 people | 1.09 * (1.02, 1.18) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) | 0.73 *** (0.63, 0.85) | 0.92 * (0.86, 0.99) | 0.76 *** (0.69, 0.85) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.15) |

| ≥7 people | 1.27 *** (1.18, 1.36) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.04) | 0.62 *** (0.53, 0.72) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 0.66 *** (0.59, 0.74) | 1.10 * (1.01, 1.21) |

| Place of residence (ref: rural) | 1.12 ** (1.03, 1.22) | 1.66 *** (1.51, 1.82) | 1.28 ** (1.09, 1.50) | 1.11 * (1.02, 1.21) | 2.74 *** (2.47, 3.04) | 0.81 *** (0.73, 0.90) |

| Hindu religion (ref: other) | 1.35 *** (1.24, 1.46) | 1.49 *** (1.37, 1.62) | 0.34 *** (0.30, 0.39) | 1.02 (0.94, 1.11) | 0.79 *** (0.71, 0.89) | 1.14 ** (1.04, 1.26) |

| Mother | ||||||

| Age, y | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.99 * (0.98, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.99 * (0.98, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) |

| Early marriage | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.85 *** (0.79, 0.92) | 1.10 (0.95, 1.27) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.12) | 0.77 *** (0.69, 0.85) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) |

| Education (ref: illiterate) | ||||||

| Primary | 1.03 (0.94, 1.14) | 1.07 (0.96, 1.18) | 1.96 *** (1.51, 2.53) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.18) | 1.57 *** (1.29, 1.90) | 0.98 (0.87, 1.12) |

| Secondary | 1.24 *** (1.14, 1.35) | 1.61 *** (1.48, 1.75) | 2.53 *** (2.05, 3.11) | 1.28 *** (1.18, 1.38) | 2.80 *** (2.41, 3.26) | 0.97 (0.87, 1.07) |

| High school or higher | 1.68 *** (1.48, 1.90) | 2.98 *** (2.59, 3.42) | 3.63 *** (2.81, 4.69) | 1.30 *** (1.15, 1.47) | 5.66 *** (4.72, 6.79) | 0.91 (0.79, 1.06) |

| Scheduled caste/tribe/OBC (ref: general) | 0.85 *** (0.79, 0.92) | 0.79 *** (0.72, 0.86) | 1.18 (1.00, 1.39) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.02) | 0.92 (0.81, 1.04) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.08) |

| Author, Year | State | Study Objective | Design/Sample Size | Enablers | Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive & Thrive (2016) [23] | Uttar Pradesh | To understand the factors that influence a mother’s diet and the feeding practices of her children. | In-depth interviews and observations (N = 360 PW and mothers), small group discussions (N = 218 husbands and mothers-in-law). | Most women were confident that they could incorporate green leafy vegetables, followed by lentils, milk, and milk products; over 40% were confident that they would be able to consume animal foods daily. The primary factors that would facilitate uptake of the recommended foods are cheaper price and support from family members. | The primary barriers preventing daily consumption of food from all food groups include affordability, availability, and food habits. |

| Andersen et al. (2003) [24] | Tamil Nadu | To describe how factors such as education level, economy, and folk dietetics influence PW’s food choice. | 24-h dietary recall with weighing of foods and recipes of dishes (N = 30 PW). | Factors such as education level, family type, pregnancy number, and folk dietetics did not have a negative effect on food choices. | Eating customs and economic factors influenced women’s food choice negatively in relation to recommendations. |

| Catherin et al. (2015) [25] | Karnataka | To assess beliefs and practices regarding nutrition during pregnancy and lactation. | 4 FGDs and 12 in-depth interviews | N/A | Avoidance of food items like ragi, papaya, mango and guava during pregnancy and reduced water consumption during the postnatal period. Beliefs like “casting an evil eye” or “color of the baby” had an influence on the food given to antenatal mother. |

| Chakrabarti et al. (2019) [26] | West Bengal | To examine food taboos in pregnancy and early lactation. | Qualitative with 4 FGDs Cross-sectional interview (N = 44 pregnant and lactating women) | N/A | Taboos on consumption of fruits (banana, papaya, jackfruit, coconut), vegetables (brinjal, leafy vegetables), meat, fish, and eggs during pregnancy to prevent miscarriage and fetal malformations and promote easy delivery. Taboos in the lactation period included avoidance of small fish, foods with multiple seeds, other "cold" foods, and fluid restriction in some areas. |

| Chakrabarti et al. (2019) [27] | India | To investigate coverage and equity of food supplementation for pregnant women. | N = 36,850 mother–child pairs in 2006 and 190,804 in 2016. | N/A | Supplementary food for PW increased between 2006 and 2016, from 19% to 53%. Key barriers to access food supplementation were being in the poorest quintiles, low schooling levels, and belonging to disadvantaged castes and tribes. |

| Craig et al. (2018) [28] | Tamil Nadu | To understand maternal dietary beliefs and practices. | Ethnographic study (N = 33). | Some women reported certain foods were beneficial during pregnancy, including apples, forest greens, egg, and various meats (chicken, mutton, rabbit, and deer). | Women avoided foods including fruit, animal products, tubers and root vegetables, legumes/pulses, and seeds during pregnancy. Most food avoidance was based on advice from elders and family members. Women reduced consumption of millets and switched to rice due to lack of availability. |

| Ganpule-Rao et al. (2020) [29] | Maharashtra | To assess food access and nutritional status among adolescents. | Cross-sectional, (N = 418). | With easier access to food, consumption of staple foods decreased and outside food increased. | N/A |

| Jhaveri et al. (2021) [30] | Uttar Pradesh | To identify key facilitators and barriers that affect behavioral adoption for diet diversity. | Qualitative in-depth interviews with 24 PW, 13 husbands, and 15 mothers-in-law. | High overall awareness and knowledge of dietary diversity recommendations among PW and family members. Family support to procure nutritious foods. | Structural opportunity barriers (financial strain, lack of food availability and accessibility) and individual barriers such as food preferences (likes and dislikes) and nausea prevented consistent behavioral change. |

| Kachwaha et al. (2020) [31] | Uttar Pradesh | To examine the cost and affordability of nutritious diets for households with PW. | 24 market and 125 household surveys. | Home production had potential to reduce the cost of nutritious diets by 35%, subsidized grains by 19%, and supplementary food by 10%. | The nutritious diet was unaffordable for 75% of households given current income levels, consumption patterns, and food prices. Household income and dietary preferences, rather than food availability, were the key barriers to obtain nutritious diets. |

| Kehoe, S. H., et al. (2019) [32] | Maharashtra | To identify barriers and facilitators to fruit and vegetable consumption among WRA. | 9 FGDs and 12 in-depth interviews | Women knew that fruit and vegetables were beneficial to health and wanted to increase the intake of these foods for themselves. | Potential barriers to fruit and vegetable consumption: (1) personal factors, (2) household dynamics, (3) social and cultural norms, (4) workload, (5) time pressures, (6) environmental factors, and (7) cost. |

| Lakshmi (2013) [33] | Andhra Pradesh | To examine the food preferences and restrictions practices by tribal PW women | In-depth interviews and direct observation. N = 600 PW aged 15–45. | Tribal women prefer iron-rich food during the antenatal period, believe it is food for growth and development of the fetus. Of the women, 60% believed nutrient-rich foods should be consumed during pregnancy. | Restrictions to consume raw papaya, sesame, coconut water, and fermented rice because they fear it may induce abortions. Of the women, 82% believed that some food items should be restricted for PW. |

| Mukhopadhyay and Sarkar (2009) [34] | Sikkim | To document pregnancy-related food practices and the social–cultural factors linked with them. | Cross-sectional study with mothers with child <1 year (N = 199). | Higher literacy and lower parity were associated with consuming special foods (milk, animal protein, pulses, green vegetables, and fruits) during pregnancy. | Taboos on different food categories, including milk, eggs, fish, meat, pulses, green vegetables, and fruits (perceived as hot and sour foods) during the postpartum were reported by 65% of mothers. |

| Nguyen et al. (2019) [21] | Uttar Pradesh | To understand the factors associated with consumption of diverse diets. | Cluster-randomized control trial with repeated cross-sectional surveys (N = 667 PW) | Higher dietary diversity and greater number of food groups consumed was associated with higher nutrition knowledge (OR = 1.2), receiving counseling (OR = 1.9), higher maternal education (OR = 1.1), and higher economic status (OR = 1.1). | Lower diet diversity and consumption of fewer number of food groups were associated with low caste status and higher parity (OR = 0.9). |

| Raghunathan et al. (2021) [35] | India | To estimate the cost of satisfying India’s national dietary guidelines and assess this diet’s affordability. | Nationally representative rural price and wage data | Nutritious diets became substantially more affordable over time. | Nutritious diets in 2011 were expensive relative to unskilled wages, constituting approximately 80–90% of female and 50–60% of male daily wages. Overall, estimate that 63–76% of the rural poor could not afford a recommended diet in 2011. |

| Rammohan et al. (2018) [36] | Uttar Pradesh | To assess the socioeconomic factors associated with dietary diversity among PW. | Cross-sectional study (N = 230) | Women with higher education and economic status were less likely to have low dietary diversity (OR = 0.4). | Dietary diversity was low among women who had no prior contact with a health professional or doctor (OR = 0.6), and those with parity of two or more (OR = 1.2). |

| Roshni (2019) [37] | Chhattisgarh | To assess feasibility to work with men and boys to improve the nutritional status of adolescent girls, pregnant women, and mothers of children <2 years. | FGDs with women, men, and adolescent boys and girls. In-depth interviews with girls and mothers. Key informant interviews with key stakeholders | N/A | Strong gendered roles inside and outside the household, social norms, reproductive health and nutrition behaviour and practice. Women had limited mobility, lower decision-making power. Women tend to eat the least amount of food and eat last in their family. |

| Sadhu et al. (2017) [38] | Rajasthan | To identify realistic and specific dietary advice/recommendations to address nutrient gaps for PW and lactating women. | Cross-sectional study (N = 2160) | Solid foods were specifically restricted during pregnancy. Maternal beliefs related to “hot” and “cold” foods relate to abortion and in causing difficulty in delivery of the baby. Women did not consume suggested foods due to lack of money and dislike of the prescribed food. | |

| Sarkar, A., et al. (2020) [39] | Madhya Pradesh | To assess how underlying factors influence nutrition diversity and food security. | Cross-sectional study | Access to food and nutrition services (OR = 1.5), exposure to nutrition counselling (OR = 1.3), and hygiene practices (OR = 1.8) were associated with higher dietary diversity and food security. | Caste status negatively influences dietary diversity, especially among women and those with household food insecurity. |

| Sharma et al. (2020) [40] | Delhi, Karnataka, Bihar, Rajasthan | To explore dietary patterns and their determinants among PW and lactating women. | Cross-sectional study. (N = 476 PW and 446 lactating women). | Women who received nutrition advice had 2–3 times higher odds of consuming a nutritious “high-mixed vegetarian diet”. | Hindus and women who lived in rural areas had higher odds of consuming a poor “low-mixed vegetarian diet” and lower odds of consuming a nutritious “high-mixed vegetarian diet” (OR = 6.9). |

| Unisa et al. (2020) [22] | Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Odisha | To measure the dietary diversity of PW. | Cross-sectional study (N = 17,680 PW) | Having at least 6 years of education, belonging to a relatively rich household, and possessing a ration card increased mean dietary diversity. | N/A |

| Author, Year | State | Study Objectives | Intervention Strategies | Design/Sample Size | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sethi, V. et al. (2019) [45] | Andhra Pradesh, Telangana | To evaluate the maternal spot feeding programs in 2 Southern Indian states | Hot cooked meal | Cross-sectional surveys with PW and lactating women (N = 720); open-ended interviews (N = 252) | Average days of consumption of hot cooked meal in a month ranged from 17 to 22 days, against the targeted 25 days. Hot cooked meal enhanced high dietary diversity (≥6 food groups; 57–59%) and consumption of eggs and milk (74–96%) among pregnant and lactating women. Computed dietary energy and protein intake was higher on days when hot cooked meal was consumed compared with on days it was not consumed. |

| National Institute of Nutrition (2016) [46] | Andhra Pradesh | To assess the effect of hot cooked meal on nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women | Hot cooked meal | Ex-post quasi-experimental design; 24-h dietary recall (N = 516) | The per capita distribution of different foods and nutrients under the HCM program was lower than program norms with 102–130 feeding days for pregnant and lactating women against the target of 150 days. About 80% of women consumed meals and felt that quality of food was moderate to good. Consumption of all foods except cereals and nutrient intakes were lower than recommended levels. |

| Babu, G.R, et al. (2020) [47] | Karnataka | To estimate the impact of hot cooked meal on gestational weight gain and hemoglobin | Hot cooked meal | Mixed methods: quantitative surveys and qualitative in-depth interviews N = 1257 PW | Mothers who consumed HCM for >75 days had improved weight gain (average 10.27 kgs from the 1st to 3rd trimester) and an increase in hemoglobin (average 0.52% from the 1st to 3rd trimester). |

| Gupta et al. (2014) [48] | India | To assess potential of fermented foods in THR | THR | Lab-based methods | A Lactobacillus plantarum strain isolated from the dosa has been found to inhibit the growth of a range of food-borne pathogens. Thus, fermented foods have potential roles on gut health and nutrition status. |

| Raghunathan et al. (2017) [49] | Odisha | To study the effects of the Mamata conditional cash transfer scheme on use of maternal nutrition services and household food security | Cash transfer | Cross-section. household survey (n = 1161 mothers with children <2 years) | Receipt of payments from the Mamata scheme is associated with a decline of 0.84 on the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale. Nearly 60% of mothers enrolled in the scheme, and over 90% of those enrolled reported receiving money from the Mamata scheme. The key bottlenecks were transfers being smaller than expected and delays in payments to beneficiaries. |

| Aaron et al. (2016) [50] | Rajasthan | To assess household coverage of atta wheat flour, edible oil, and salt. | Food fortification | Cross-section. N = 4627 households (including caregiver and child <2 years) | Only 7% of the atta wheat flour was classified as fortifiable, and only 6% was actually fortified (mostly inadequately). For oil, almost 90% of edible oil consumed by households was classified as fortifiable, but only 24% was fortified. 66% of households used adequately fortified salt. The key bottleneck was most households (82%) reported purchasing whole grain and milling at home/local mills. A second major bottleneck was lack of monitoring and evaluation of compliance to fortification protocols. |

| Chakrabarti et al. (2019) [51] | Punjab, Tamil Nadu vs. Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka | To assess impact of subsidized fortified wheat on anemia among PW | Food fortification | District panel. N = 10,186 Difference-in-difference analysis | In northern India, no impact on Hb or anemia reduction was found, as expected, given that the intervention targeted only non-poor households and demand for fortified wheat was low. In southern India, where intervention coverage was high, there was no impact on Hb but an impact on anemia reduction (8%), which was unexpected given low consumption of wheat in this predominantly rice-eating region. |

| Collison et al. (2015) [52] | Bihar | To explore the acceptability and utility of a low-cost and simple-to-use feeding toolkit of optimal dietary practices | BCC | 16 FGDs and 8 key informant interviews; 14 days of user testing with 60 PW, lactating women, and RDW | After using the toolkit, the proportion of pregnant and breastfeeding women consuming an extra portion of food per day increased from 0% to 100%, and the number of meals taken per day increased from 2–3 to 3–4 meals. The toolkit, which is made of plastic, was well accepted by the community, although the communities recommended manufacturing the bowl and spoon in steel. Some mothers-in-law were not present during initial counseling, thus worried of the toolkit benefits and did not allow PW to use them. Some PW were hesitant to use the tools for fear that their morning sickness would intensify. |

| Garg and Kashyap (2006) [53] | Uttar Pradesh | To assess the effect of counseling on dietary intakes during pregnancy | BCC | Baseline and endline survey (N = 100 PW) | There was a significant increase in the amount of all food groups and nutrients consumed among those who received nutrition education post-intervention. However, the improvements still did not meet adequate intakes, except for vitamin A and C. Husbands and mothers-in-law played an important role in motivating women to adopt recommended behaviors. |

| Nguyen et al. (2021) [54] | Uttar Pradesh | To assess the impact of Alive & Thrive nutrition counseling interventions on maternal dietary diversity | BCC | Cluster-randomized control trial with repeated cross-sectional surveys (N = 660 PW) | Women in the intervention arm received more counseling on core nutrition messages (DID: 10–23 pp). Maternal food group consumption (∼4 food groups) and probability of adequacy of micronutrients (∼20%) remained low in both arms. Interventions showed modest impact on consumption of vitamin A-rich foods (10 pp, 11 g/d) and other vegetables and fruits (22–29 g/d). Factors explaining modest impacts on dietary diversity included limited resources and food preferences. |

| Shivalli et al. (2015) [55] | Uttar Pradesh | To examine the effectiveness of a BCC intervention on dietary intake during pregnancy. | BCC | Community-based quasi-experimental study with a control group (N = 86 PW) | The mean intake of protein increased by 1.8 grams in the intervention group and decreased by 1.8 grams in the control group. More than two-thirds of PW in the intervention group were taking one extra meal compared to only one-third in the control group. More than half of PW in both study groups decreased their dietary intake since conception. |

| Daivadanam et al. (2018) [56] | Kerala | To assess the effectiveness of a BCC intervention on dietary intake at the individual and household level | BCC | Community-based cluster-randomized controlled trial (N = 471) | There was significant, modest increase in fruit intake from baseline in the intervention arm (12.5%), but no significant impact of the intervention on vegetable intake over the control arm. Monthly household consumption of salt, sugar, and oil was greatly reduced in the intervention arm compared to the control arm, with the actual effect sizes showing an overall reduction by 45%, 40%, and 48%, respectively. |

| Vani Sethi et al. (2019) [57] | Delhi and Uttar Pradesh | To develop a maternal service package of interventions for mothers-to-be integrated in routine services at nutrition rehabilitation centers | BCC | 427 mothers of inpatient children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) | Universal interventions for all mothers not at nutritional risk include hospital diet, micronutrient supplementation and deworming, group-based nutrition education and counselling. Additional interventions for mothers at some nutritional risk include 15 minutes of individual, mother-focused tailoring to the mother’s specific nutritional risk. Mothers at severe nutritional risk got therapeutic foods (F-100). Evaluation was not done. |

| Beesabathuni et al. (2021) [58] | Madhya Pradesh | To test a poultry cooperative model to improve women empowerment, nutrition conditions, and SES | Nutrition-sensitive agriculture | Quasi-experimental study | Income increased by eight times per household, and more eggs became available in the community. Women and children now have access to an egg every other day |

| Kadiyala et. al (2021) [59] | Odisha | To test the effects of three nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions on maternal diet diversity | Nutrition-sensitive agriculture | Four-arm, observer-blind, cluster-randomized trial (N = ~4736) | An increase in the proportion of mothers consuming at least five of ten food groups was seen in the nutrition-sensitive agriculture videos (adjusted RR 1.2) and nutrition-sensitive agriculture videos + participatory learning and action (RR: 1.30) groups compared with the control group, but not in the group that received only nutrition-specific videos (RR: 1.16). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, P.H.; Kachwaha, S.; Tran, L.M.; Sanghvi, T.; Ghosh, S.; Kulkarni, B.; Beesabathuni, K.; Menon, P.; Sethi, V. Maternal Diets in India: Gaps, Barriers, and Opportunities. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3534. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103534

Nguyen PH, Kachwaha S, Tran LM, Sanghvi T, Ghosh S, Kulkarni B, Beesabathuni K, Menon P, Sethi V. Maternal Diets in India: Gaps, Barriers, and Opportunities. Nutrients. 2021; 13(10):3534. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103534

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Phuong Hong, Shivani Kachwaha, Lan Mai Tran, Tina Sanghvi, Sebanti Ghosh, Bharati Kulkarni, Kalpana Beesabathuni, Purnima Menon, and Vani Sethi. 2021. "Maternal Diets in India: Gaps, Barriers, and Opportunities" Nutrients 13, no. 10: 3534. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103534

APA StyleNguyen, P. H., Kachwaha, S., Tran, L. M., Sanghvi, T., Ghosh, S., Kulkarni, B., Beesabathuni, K., Menon, P., & Sethi, V. (2021). Maternal Diets in India: Gaps, Barriers, and Opportunities. Nutrients, 13(10), 3534. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103534