MALDI-TOF MS Characterisation of the Serum Proteomic Profile in Insulin-Resistant Normal-Weight Individuals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Groups

2.2. Serum Samples Pretreatment

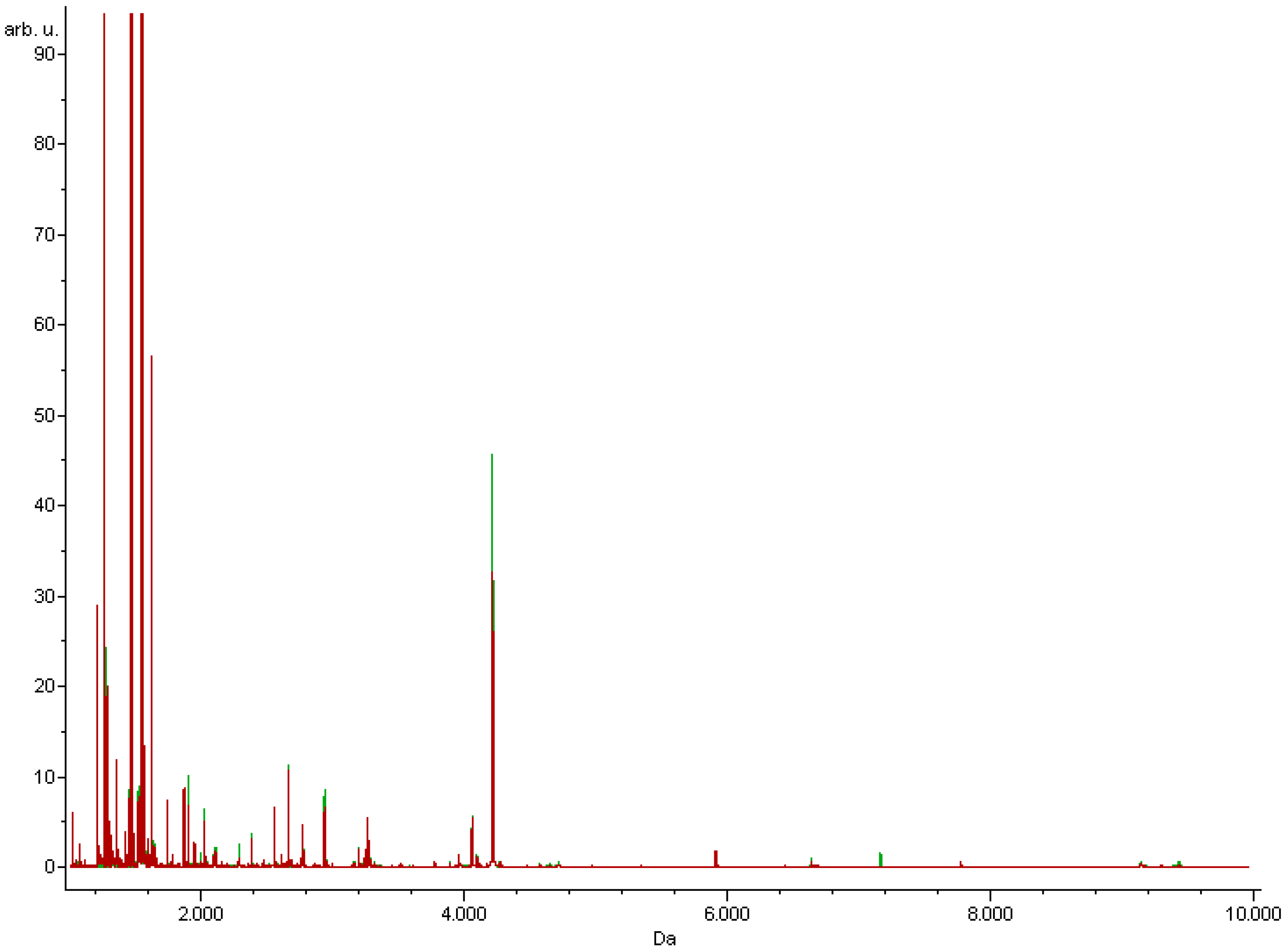

2.3. MALDI-TOF Proteomic Profiling

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. NanoLC-MALDI-TOF/TOF MS Identification of the Discriminative Peaks

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freeman, A.M.; Pennings, N. Insulin resistance. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Farrokhi, F.R.; Butler, A.E.; Sahebkar, A. Insulin resistance: Review of the underlying molecular mechanisms. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8152–8161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matulewicz, N.; Karczewska-Kupczewska, M. Insulin resistance and chronic inflammation. Postępy Hig. I Med. Doświadczalnej 2016, 70, 1245–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek-Tupikowska, G.; Stachowska, B.; Miazgowski, T.; Krzyżanowska-Świniarska, B.; Katra, B.; Jaworski, M.; Kuliczkowska-Płaksej, J.; Rokita, A.J.; Tupikowska, M.; Bolanowski, M.; et al. Evaluation of the prevalence of metabolic obesity and normal weight among the Polish population. Endokrynol. Pol. 2012, 63, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Östenson, C.-G. The pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus: An overview. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2001, 171, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormazabal, V.; Nair, S.; Elfeky, O.; Aguayo, C.; Salomon, C.; Zuñiga, F.A. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowicz-Frontczak, A.; Majchrzak, A.; Zozulińska-Ziółkiewicz, D. Insulin resistance in endocrine disorders—treatment options. Endokrynol. Pol. 2017, 68, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanase, D.M.; Gosav, E.M.; Costea, C.F.; Ciocoiu, M.; Lacatusu, C.M.; Maranduca, M.A.; Ouatu, A.; Floria, M. The Intricate Relationship between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), Insulin Resistance (IR), and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.R.; Matta, S.T.; Haymond, M.W.; Chung, S.T. Measuring Insulin Resistance in Humans. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2021, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szurkowska, M.; Szafraniec, K.; Gilis-Januszewska, A.; Szybiński, Z.; Huszno, B. Insulin resistance indices in population-based study and their predictive value in defining metabolic syndrome. Prz. Epidemiol. 2005, 59, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Crespo, J.; López, J.L. A better understanding of molecular mechanisms underlying human disease. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2007, 1, 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyohara, M.; Shirakawa, J.; Okuyama, T.; Kimura, A.; Togashi, Y.; Tajima, K.; Hirano, H.; Terauchi, Y. Serum Quantitative Proteomic Analysis Reveals Soluble EGFR To Be a Marker of Insulin Resistance in Male Mice and Humans. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 4152–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, J.; Liao, B.; Peng, X.; Li, T.; Li, J.; Tan, Q.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Proteomics analysis of potential serum biomarkers for insulin resistance in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and ?-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basics on data preparation model generation and spectra classification. In ClinProTools 3.0. Software for Biomarker Detection and Evaluation User Manual; Bruker Daltonics: Bremen, Germany, 2011; pp. 51–96.

- Matuszewska, E.; Matysiak, J.; Bręborowicz, A.; Olejniczak, K.; Kycler, Z.; Kokot, Z.J.; Matysiak, J. Proteomic fea-tures characterization of Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2019, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiatly, A.; Horala, A.; Hajduk, J.; Matysiak, J.; Nowak-Markwitz, E.; Kokot, Z.J. MALDI-TOF-MS analysis in discovery and identi-fication of serum proteomic patterns of ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, J.; Matuszewska, E.; Kowalski, M.L.; Kosiński, S.W.; Smorawska-Sabanty, E.; Matysiak, J. Associa-tion between Venom Immunotherapy and Changes in Serum Protein—Peptide Patterns. Vaccines 2021, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P02671 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Raynaud, E.; Perez-Martin, A.; Brun, J.-F.; Aïssa-Benhaddad, A.; Fédou, C.; Mercier, J. Relationships between fibrinogen and insulin resistance. Atherosclerosis 2000, 150, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, G.; Hedblad, B.; Stavenow, L.; Lind, P.; Janzon, L.; Lindgärde, F. Inflammation-Sensitive Plasma Proteins Are Associated With Future Weight Gain. Diabetes 2003, 52, 2097–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P02768 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Ishizaka, N.; Ishizaka, Y.; Nagai, R.; Toda, E.-I.; Hashimoto, H.; Yamakado, M. Association between serum albumin, carotid atherosclerosis, and metabolic syndrome in Japanese individuals. Atherosclerosis 2007, 193, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.C.; Seo, S.H.; Hur, K.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.-S.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, W.-Y.; Rhee, E.J.; Oh, K.W. Association between Serum Albumin, Insulin Resistance, and Incident Diabetes in Nondiabetic Subjects. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 28, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, C.E.; Kalinyak, J.E.; Hutson, S.M.; Jefferson, L.S. Stimulation of albumin gene transcription by insulin in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1987, 252, C205–C214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peavy, D.E.; Taylor., J.M.; Jefferson, L.S. Time course of changes in albumin synthesis and mRNA in diabetic and insulintreated diabetic rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1985, 248, E656–E663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P01042 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Benabdelkamel, H.; Masood, A.; Okla, M.; Al-Naami, M.Y.; Alfadda, A.A. A Proteomics-Based Approach Reveals Differential Regulation of Urine Proteins between Metabolically Healthy and Unhealthy Obese Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, H.; Kang, G.; Cao, B.; Kang, Q.; Li, R.; Zhu, X.; Rao, W.; Yu, Q. Kininogen-1 as a protein biomarker for schizophrenia through mass spectrometry and genetic association analyses. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.; Li, R.; Kang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Yan, L.; Yu, Y.; Yu, Q. Fibrinogen and Kininogen are Potential Serum Protein Biomarkers for Depressive Disorder. Clin. Lab. 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Lin, C.; Li, X.; Fang, X.; Zhong, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, S. Identification of Kininogen 1 as a Serum Protein Marker of Colorectal Adenoma in Patients with a Family History of Colorectal Cancer. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P01024 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Wang, B.; Li, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, L.; Luo, R.; Cheng, Q.; Qing, H. Serum complement C3 has a stronger association with insulin resistance than high sensitive C-reactive protein in non-diabetic Chinese. Inflamm. Res. 2011, 60, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano-Castillo, D.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Fernandez-Garcia, J.C.; Clemente-Postigo, M.; Castro-Cabezas, M.; Tinahones, F.J.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Cardona, F. Complement Factor C3 Methylation and mRNA Expression Is Associated to BMI and Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Genes 2018, 9, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursini, F.; Grembiale, A.; Naty, S.; Grembiale, R.D. Serum complement C3 correlates with insulin resistance in never treated psoriatic arthritis patients. Clin. Rheumatol. 2014, 33, 1759–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Q.; Song, Y.; Tian, B.; Cheng, Q.; Qing, H.; Zhong, L.; Xia, W. Serum complement C3 has a stronger association with insulin resistance than high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1749–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkhaneh, M.; Qorbani, M.; Mohajeri-Tehrani, M.R.; Hoseini, S. Association of serum complement C3 with metabolic syndrome components in normal weight obese women. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2017, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P02787 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaquero, M.P.; Martínez-Maqueda, D.; Gallego-Narbón, A.; Zapatera, B.; Pérez-Jiménez, J. Relationship between iron status markers and insulin resistance: An exploratory study in subjects with excess body weight. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galaris, D.; Barbouti, A.; Pantopoulos, K. Iron homeostasis and oxidative stress: An intimate relationship. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P01857 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

| Parameters | Research Group | Control Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | 21 | 43 | |

| Men | 4 | 13 | 0.3858 |

| Women | 17 | 30 | |

| Age [years] | 44.10 ± 13.26 | 43.26 ± 12.26 | 0.8426 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 22.18 ± 2.27 | 22.61 ± 2.04 | 0.2671 |

| Glucose [mg/dL] | 96.38 ± 17.87 | 87.09 ± 12.85 | <0.0001 |

| Insulin [mmol/L] | 21.13 ± 9.93 | 6.91 ± 3.95 | 0.0015 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.99 ± 2.07 | 1.54 ± 1.23 | <0.0001 |

| GA | QC | SNN |

|---|---|---|

| 1321.27 3240.65 1546.37 3964.52 1305.22 1207.20 1897.25 3278.35 1077.93 9133.97 1568.41 1519.79 8916.44 4122.57 3996.08 | 1020.86 1207.20 1269.76 1283.24 1305.22 1350.78 | 2755.13 |

| GA | QC | SNN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-validation (%) | 44.15 | 57.6 | 80.56 |

| Recognition capability (%) | 90.72 | 56.51 | 46.42 |

| Correct classified (%) | |||

| Insulin resistance | 71.4 | 14.3 | 92.9 |

| Control | 96.3 | 100 | 0 |

| No. | Precursor Ion m/z | Peptide Fragmentation Sequence | UniProtKB-ID | Protein Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1321.27 | K.STSGGTAALGCLVK.D | IGHG1_HUMAN | Ig gamma-1 chain |

| 2. | 1546.37 | A.DSGEGDFLAEGGGVR.G | FIBA_HUMAN | Fibrinogen alpha chain |

| 1207.20 | G.EGDFLAEGGGVR.G | |||

| 1077.93 | E.GDFLAEGGGVR.G | |||

| 1020.86 | G.DFLAEGGGVR.G | |||

| 1350.78 | D.SGEGDFLAEGGGV.R | |||

| 3. | 1305.22 | K.ECCEKPLLEK.S | ALBU_HUMAN | Serum albumin |

| 4. | 1568.41 | H.GHEQQHGLGHGHKF.K | KNG1-HUMAN | Kininogen-1 |

| 5. | 1519.79 | G.SPMYSIITPNILR.L | CO3_HUMAN | Complement C3 |

| 2755.13 | R.EGVQKEDIPPADLSDQVPDTESETR.I | |||

| 6. | 1283.24 | K.EGYYGYTGAFR.C | TRFE_HUMAN | Serotransferrin |

| Protein Name | Precursor Ion m/z | Spearmana’s R-Value | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Research Group | Control Group | |||

| Ig gamma-1 chain | 1321.27 | −0.17 | −0.17 | −0.12 | statistically insignificant >0.05 |

| Fibrinogen alpha chain | 1020.86 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.07 | |

| 1077.93 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.19 | ||

| 1207.20 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.15 | ||

| 1350.78 | −0.04 | −0.24 | −0.17 | ||

| 1546.37 | −0.16 | −0.39 | 0.13 | ||

| Serum albumin | 1305.22 | −0.14 | −0.20 | −0.11 | |

| Kininogen-1 | 1568.41 | −0.14 | −0.28 | −0.16 | |

| Complement C3 | 1519.79 | −0.14 | −0.28 | 0.09 | |

| 2755.13 | 0.13 | −0.46 | 0.34 | ||

| Serotransferrin | 1283.24 | −0.09 | −0.26 | −0.31 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pastusiak, K.; Matuszewska, E.; Pietkiewicz, D.; Matysiak, J.; Bogdanski, P. MALDI-TOF MS Characterisation of the Serum Proteomic Profile in Insulin-Resistant Normal-Weight Individuals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13113853

Pastusiak K, Matuszewska E, Pietkiewicz D, Matysiak J, Bogdanski P. MALDI-TOF MS Characterisation of the Serum Proteomic Profile in Insulin-Resistant Normal-Weight Individuals. Nutrients. 2021; 13(11):3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13113853

Chicago/Turabian StylePastusiak, Katarzyna, Eliza Matuszewska, Dagmara Pietkiewicz, Jan Matysiak, and Pawel Bogdanski. 2021. "MALDI-TOF MS Characterisation of the Serum Proteomic Profile in Insulin-Resistant Normal-Weight Individuals" Nutrients 13, no. 11: 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13113853

APA StylePastusiak, K., Matuszewska, E., Pietkiewicz, D., Matysiak, J., & Bogdanski, P. (2021). MALDI-TOF MS Characterisation of the Serum Proteomic Profile in Insulin-Resistant Normal-Weight Individuals. Nutrients, 13(11), 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13113853