Breastfeeding Practices among Adolescent Mothers and Associated Factors in Bangladesh (2004–2014)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Outcome and Confounding Factors

- EBF was defined as the proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk only and no other solids or liquids except for vitamins, minerals, medicines or oral rehydration solution;

- PBF was defined as the proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk and water, water-based liquids such as sugar water and juices but not infant formula or milk;

- EIBF was defined as the proportion of children aged 0–23 months who were put to the breast within one hour of birth and,

- BotBF was defined as the proportion of children aged 0–23 months who received any food or liquid including non-human milk and formula, any liquid (including breast milk) or semi-solid food from a bottle with nipple/teat.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

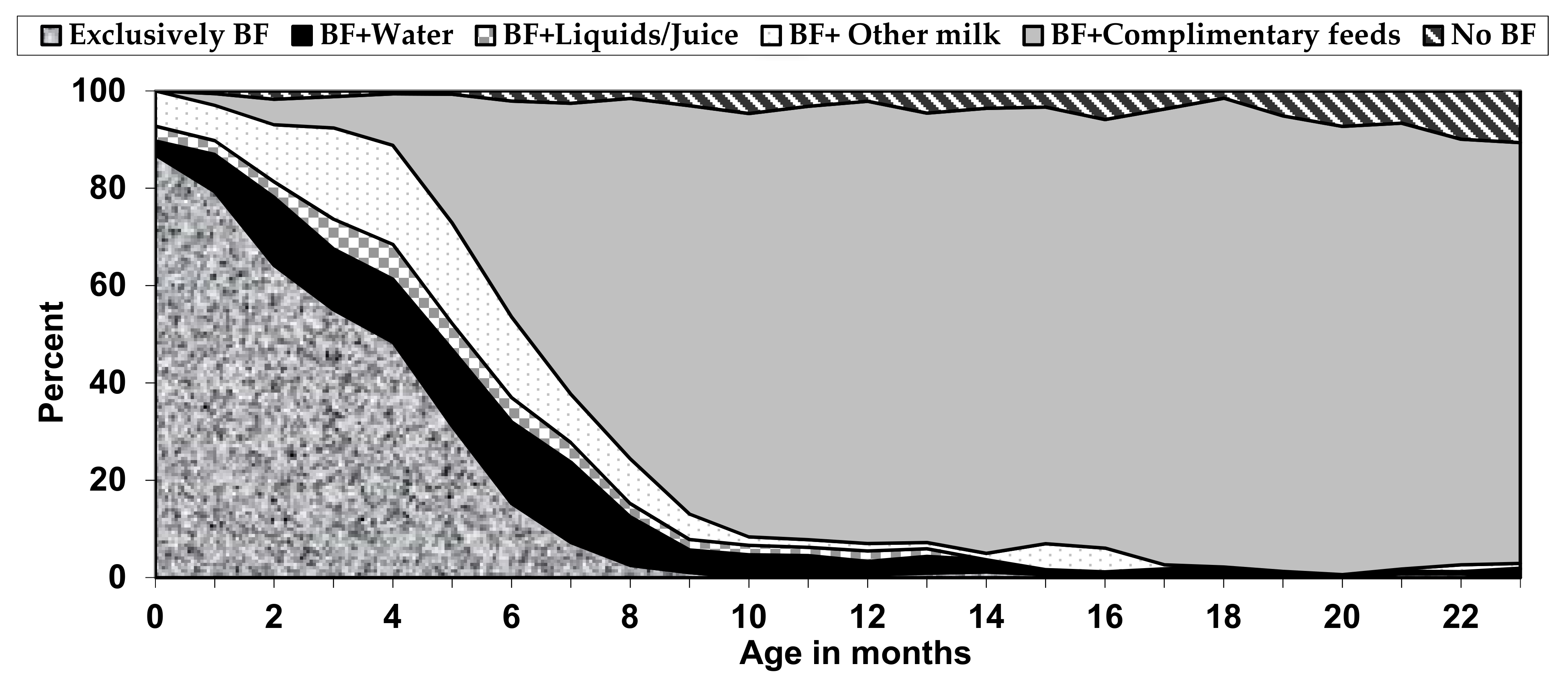

3.2. Breastfeeding and Infant Feeding Indicators

3.3. Determinants of Selected Feeding Indicators

3.3.1. Factors Associated with Delayed Initiation of Breastfeeding and Bottle-Feeding

3.3.2. Factors Associated with Exclusive Breastfeeding and Predominant Breastfeeding

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- UNFPA. Girlhood, Not Motherhood: Preventing Adolescent Pregnancy; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Darroch, J.; Woog, V.; Bankole, A.; Ashford, L.S. Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits of Meeting the Contraceptive Needs of Adolescents; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund-Bangladesh. Young People Online; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://bangladesh.unfpa.org/en/topics/young-people-10 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- World Health Organization. Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): Guidance to Support Country Implementation; Contract No., Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, R.C.; Olsen, H.E.; Ikeda, C.T.; Echko, M.M.; Ballestreros, K.E.; Manguerra, H.; Martopullo, I.; Millear, A.; Shields, C.; Smith, A.; et al. Diseases, injuries, and risk factors in child and adolescent health, 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2017 Study. JAMA Pediatrics 2019, 173, e190337. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; UNICEF; Mathers, C. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; França, G.V.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C.; et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogbo, F.A.; Page, A.; Idoko, J.; Claudio, F.; Agho, K.E. Diarrhoea and Suboptimal Feeding Practices in Nigeria: Evidence from the National Household Surveys. Paediatr. Périnat. Epidemiol. 2016, 30, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbo, F.A.; Agho, K.; Ogeleka, P.; Woolfenden, S.; Page, A.; Eastwood, J. Infant feeding practices and diarrhoea in sub-Saharan African countries with high diarrhoea mortality. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turfkruyer, M.; Verhasselt, V. Breast milk and its impact on maturation of the neonatal immune system. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 28, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Coates, M.M.; Coggeshall, M.; Dandona, L.; Diallo, K.; Franca, E.B.; Fraser, M.; Fullman, N.; Gething, P.W.; et al. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1725–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, K.Y.; Page, A.; Arora, A.; Ogbo, F.A. Associations between infant and young child feeding practices and acute respiratory infection and diarrhoea in Ethiopia: A propensity score matching approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.J.; Baird, K.; Mazerolle, P.; Broidy, L. Exploring the influence of psychosocial factors on exclusive breastfeeding in Bangladesh. Arch. Women’s Mental Health 2017, 20, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Kim, S.S.; Tran, L.M.; Menon, P.; Frongillo, E.A. Early breastfeeding practices contribute to exclusive breastfeeding in Bangladesh, Vietnam and Ethiopia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e13012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hossain, M.; Islam, A.; Kamarul, T.; Hossain, G. Exclusive breastfeeding practice during first six months of an infant’s life in Bangladesh: A country based cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, M.A.; Khan, M.N.; Akter, S.; Rahman, A.; Alam, M.M.; Khan, M.A.; Rahman, M. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice in Bangladesh: Evidence from nationally representative survey data. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.; Khan, A.N.S.; Tasnim, F.; Chowdhury, M.A.K.; Billah, S.M.; Karim, T.; El-Arifeen, S.; Garnett, S.P. Prevalence and determinants of initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth: An analysis of the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogbo, F.A.; Eastwood, J.; Page, A.; Arora, A.; McKenzie, A.; Jalaludin, B.; Tennant, E.; Miller, E.; Kohlhoff, J.; Noble, J.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of cessation of exclusive breastfeeding in the early postnatal period in Sydney, Australia. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2016, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogbo, F.A.; Ezeh, O.K.; Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J.; Ahmed, K.Y.; Eastwood, J.; Khanlari, S.; Naz, S.; Senanayake, P.; Ahmed, K.Y.; et al. Determinants of Exclusive Breastfeeding Cessation in the Early Postnatal Period among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Australian Mothers. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mossman, M.; Heaman, M.I.; Dennis, C.-L.; Morris, M. The Influence of Adolescent Mothers’ Breastfeeding Confidence and Attitudes on Breastfeeding Initiation and Duration. J. Hum. Lact. 2008, 24, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Senanayake, P.; O’Connor, E.; Ogbo, F.A. National and rural-urban prevalence and determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in India. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luthje, E.H.; Mainardi, T.E.B.; Luthje, G.M.H.; Lopez, E.A. Prevalence of Exclusive Breastfeeding and Factors Associated with Exclusive Breastfeeding in Adolescent Mothers in an Upper Middle Income Country. Off. J. Am. Acad. Pediatrics 2020, 146, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agho, K.E.; Ogeleka, P.; Ogbo, F.A.; Ezeh, O.K.; Eastwood, J.G.; Page, A. Trends and Predictors of Prelacteal Feeding Practices in Nigeria (2003–2013). Nutrients 2016, 8, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hackett, K.M.; Mukta, U.S.; Jalal, C.S.; Sellen, D.W. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions on infant and young child nutrition and feeding among adolescent girls and young mothers in rural Bangladesh. Matern. Child Nutr. 2015, 11, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Nomani, D.; Taneepanichskul, S. Trends and Determinants of EBF among Adolescent Children Born to Adolescent Mothers in Rural Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Population and Training Mitra and Associates D [Bangladesh]; ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2013. In National Institute of Population and Training; National Institute of Population and Training and ICF International: Calverton, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, R.; Baines, S.K.; Agho, K.E.; Dibley, M.J. Determinants of breastfeeding indicators among children less than 24 months of age in Tanzania: A secondary analysis of the 2010 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e001529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dhami, M.V.; Ogbo, F.A.; Diallo, T.M.; Agho, K.; on behalf of the Global Maternal and Child Health Research Collaboration (GloMACH). Regional Analysis of Associations between Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices and Diarrhoea in Indian Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USAID; AED; FANTA 2; UCDavis; IFPRI; UNICEF; WHO. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices I; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Agho, K.E.; Ezeh, O.K.; Ghimire, P.R.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Stevens, G.J.; Tannous, W.K.; Fleming, C.; Ogbo, F.A.; Global Maternal and Child Health Research Collaboration (GloMACH). Exclusive Breastfeeding Rates and Associated Factors in 13 “Economic Community of West African States” (ECOWAS) Countries. Nutrients 2019, 11, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dhami, M.V.; Ogbo, F.A.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Agho, K.E. Prevalence and factors associated with complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 months in India: A regional analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogbo, F.A.; Dhami, M.V.; Awosemo, A.O.; Olusanya, B.O.; Olusanya, J.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Ghimire, P.R.; Page, A.; Agho, K.E. Regional prevalence and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in India. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2019, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hector, D.; King, L.; Webb, K.; Heywood, P. Factors affecting breastfeeding practices. Applying a conceptual framework. J. N. S. W. Public Health Bull. 2005, 16, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filmer, D.; Pritchett, L.H. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 2001, 38, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. UNICEF Statistics, Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS)—Assessing the Economic Status of Households. 2005. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/statistics/index_24302.html (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Benova, L.; Siddiqi, M.; Abejirinde, I.O.; Badejo, O. Time trends and determinants of breastfeeding practices among adolescents and young women in Nigeria, 2003–2018. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, A.-A.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Hagan, J.E., Jr.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Abodey, E.; Odoi, A.; Agbaglo, E.; Sambah, F.; Tackie, V.; Schack, T. Mass media exposure and women’s household decision-making capacity in 30 sub-Saharan African countries: Analysis of demographic and health surveys. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 581614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senarath, U.; Gunawardena, N.S. Women’s autonomy in decision making for health care in South Asia. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2009, 21, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.E.; Perkins, J.; Islam, S.; Siddique, A.B.; Moinuddin, M.; Anwar, M.R.; Mazumder, T.; Ansar, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Raihana, S.; et al. Knowledge and involvement of husbands in maternal and newborn health in rural Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hackett, K.M.; Mukta, U.S.; Jalal, C.S.B.; Sellen, D.W. A qualitative study exploring perceived barriers to infant feeding and caregiving among adolescent girls and young women in rural Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Takahashi, K.; Ganchimeg, T.; Ota, E.; Vogel, J.P.; Souza, J.P.; Laopaiboon, M.; Castro, C.P.; Jayaratne, K.; Ortiz-Panozo, E.; Lumbiganon, P.; et al. Prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding and determinants of delayed initiation of breastfeeding: Secondary analysis of the WHO Global Survey. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep44868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karim, F.; Billah, S.M.; Chowdhury, M.A.K.; Zaka, N.; Manu, A.; El Arifeen, S.; Khan, A.N.S. Initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth and its determinants among normal vaginal deliveries at primary and secondary health facilities in Bangladesh: A case-observation study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shamim, S.; Jamalvi, S.W.; Naz, F. Determinants of bottle use amongst economically disadvantaged mothers. J. Ayub Med Coll. Abbottabad JAMC 2006, 18, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, S.N.; Verma, A.; Dhumal, G.G. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding breastfeeding in postpartum mothers at a tertiary care institute during a public health awareness campaign. Breastfeed. Rev. 2017, 25, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrul, N.; Hafid, F.; Ramadhan, K.; Suza, D.E.; Efendi, F. Factors associated with bottle feeding in children aged 0–23 months in Indonesia. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacking, R.; Nyqvist, K.H.; Ewald, U. Effects of socioeconomic status on breastfeeding duration in mothers of preterm and term infants. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibley, M.J.; Roy, S.K.; Senarath, U.; Patel, A.; Tiwari, K.; Agho, K.; Mihrshahi, S.; for the South Asia Infant Feeding Research Network (SAIFRN). Across-Country Comparisons of Selected Infant and Young Child Feeding Indicators and Associated Factors in Four South Asian Countries. Food Nutr. Bull. 2010, 31, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazir, T.; Akram, D.-S.; Nisar, Y.B.; Kazmi, N.; Agho, K.E.; Abbasi, S.; Khan, A.M.; Dibley, M.J. Determinants of suboptimal breast-feeding practices in Pakistan. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 16, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ogbo, F.A.; Akombi, B.J.; Ahmed, K.Y.; Rwabilimbo, A.G.; Ogbo, A.O.; Uwaibi, N.; Ezeh, O.K.; Agho, K.; on behalf of the Global Maternal and Child Health Research Collaboration (GloMACH). Breastfeeding in the Community—How Can Partners/Fathers Help? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Kabir, I.; Roy, S.K.; Agho, K.E.; Senarath, U.; Dibley, M.J.; for the South Asia Infant Feeding Research Network (SAIFRN). Determinants of Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices in Bangladesh: Secondary Data Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Food Nutr. Bull. 2010, 31, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gila-Díaz, A.; Carrillo, G.H.; López de Pablo, Á.L.; Arribas, S.M.; Ramiro-Cortijo, D. Association between maternal postpartum depression, stress, optimism, and breastfeeding pattern in the first six months. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, K.; Lenters, L.; Vandermorris, A.; LaFleur, C.; Newton, S.; Ndeki, S.; Zlotkin, S. How can engagement of adolescents in antenatal care be enhanced? Learning from the perspectives of young mothers in Ghana and Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipojola, R.; Lee, G.T.; Chiu, H.-Y.; Chang, P.-C.; Kuo, S.-Y. Determinants of breastfeeding practices among mothers in Malawi: A population-based survey. Int. Health 2019, 12, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Allen, L.H.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Caulfield, L.E.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Mathers, C.; Rivera, J. Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008, 371, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqui, A.H.; Ahmed, S.; El-Arifeen, S.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Rosecrans, A.M.; Mannan, I.; Rahman, S.M.; Begum, N.; Mahmud, A.B.; Seraji, H.R.; et al. Effect of timing of first postnatal care home visit on neonatal mortality in Bangladesh: A observational cohort study. BMJ 2009, 339, b2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Individual-level factors | ||

| Mother’s religion (n = 2553) | ||

| Islam | 2374 | 93.0 |

| Others $ | 179 | 7.0 |

| Maternal working status | ||

| Non-working | 2320 | 90.8 |

| Working (past 12 months)s | 234 | 9.2 |

| Maternal education | ||

| No education | 268 | 10.5 |

| Primary | 811 | 31.8 |

| Secondary and higher | 1475 | 57.8 |

| Partner’s education | ||

| No education | 596 | 23.3 |

| Primary | 1064 | 41.7 |

| Secondary and higher | 892 | 34.9 |

| Husband’s occupation (n = 2552) | ||

| Non-agricultural | 1582 | 61.9 |

| Agricultural | 667 | 26.1 |

| Not working | 305 | 12.0 |

| Mother’s age | ||

| 12–18 years | 1062 | 41.6 |

| 18–19 years | 1492 | 58.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 2527 | 99.0 |

| Formerly married ^ | 26 | 1.0 |

| Birth order | ||

| First-born | 2083 | 81.6 |

| 2nd–4th | 471 | 18.4 |

| Preceding birth interval | ||

| No previous birth | 2083 | 81.6 |

| Yes | 467 | 18.3 |

| Sex of baby | ||

| Male | 1303 | 51.0 |

| Female | 1251 | 49.0 |

| Number of living children | ||

| 1 | 2157 | 84.5 |

| 2–4 | 396 | 15.5 |

| Age of child (in months) | ||

| 0–5 | 745 | 29.2 |

| 6–11 | 717 | 28.1 |

| 12–17 | 628 | 24.6 |

| 18–23 | 464 | 18.2 |

| Combined mode and place of delivery (n = 2548) | ||

| Caesarean | 299 | 12.1 |

| Vaginal | 289 | 11.9 |

| Home | 1955 | 75.7 |

| Type of delivery assistance (n = 2543) | ||

| Health professional | 549 | 21.2 |

| Non-health professional | 2005 | 78.4 |

| Antenatal Clinic (ANC) visits | ||

| 8+ | 104 | 4.1 |

| 4–7 | 508 | 19.9 |

| 1–3 | 1179 | 46.2 |

| None | 763 | 29.9 |

| Postnatal check-up | ||

| 0–2 days | 631 | 24.7 |

| After 2 days | 295 | 11.6 |

| No postnatal check-up | 1628 | 63.8 |

| Mother’s BMI (n = 2521) | ||

| <18.5 | 754 | 29.5 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1675 | 65.6 |

| 25+ | 92 | 3.6 |

| Exposure to Media | ||

| Mother reading newspapers (n = 2552) | ||

| Not at all | 2196 | 86.0 |

| Yes # | 355 | 13.9 |

| Mother listening to radio | ||

| Not at all | 1950 | 76.3 |

| Yes # | 604 | 23.7 |

| Mother watching television (n = 2552) | ||

| Not at all | 1056 | 41.4 |

| Yes # | 1496 | 58.6 |

| Household-level factors | ||

| Household wealth Index | ||

| Richest | 497 | 19.5 |

| Richer | 542 | 21.2 |

| Middle | 507 | 19.9 |

| Poorer | 503 | 19.7 |

| Poorest | 505 | 19.8 |

| Decision-making (Autonomy) | ||

| No Decision (0 scores) | 1061 | 41,5 |

| Some Decisions (1–2 scores) | 801 | 31.4 |

| All Decisions (3 scores) | 693 | 27.1 |

| Community-level factors | ||

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 516 | 20.2 |

| Rural | 2038 | 79.8 |

| Geographical Region without Rangpur | ||

| Barisal | 145 | 6.1 |

| Chittagong | 534 | 22.5 |

| Dhaka | 791 | 33.3 |

| Khulna | 266 | 11.2 |

| Rajshahi | 494 | 20.8 |

| Sylhet | 145 | 6.1 |

| Geographical Region with Rangpur | ||

| Barisal | 145 | 5.7 |

| Chittagong | 534 | 20.9 |

| Dhaka | 791 | 31.0 |

| Khulna | 266 | 10.4 |

| Rajshahi | 494 | 19.4 |

| Sylhet | 145 | 5.7 |

| Rangpur | 178 | 7.0 |

| Breastfeeding Indicators | N * | n * | Rate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early initiation of breastfeeding rate a | |||

| Yes | 2554 | 1078 | 42.2 (39.7,44.8) |

| Ever breastfed rate a | |||

| Yes | 2554 | 2546 | 99.7 (99.3, 99.9) |

| Bottle-feeding rate a^ | |||

| Yes | 2032 | 319 | 15.7 (13.7, 17.9) |

| Current breastfeeding rate a | |||

| Yes | 2554 | 2546 | 99.7 (99.3, 99.9) |

| Age-appropriate breastfeeding | |||

| Yes | 2554 | 1938 | 75.9 (73.8,77.8) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding rate b | |||

| Yes | 745 | 395 | 53.0 (48.6, 57.3) |

| Predominant breastfeeding rate b | |||

| Yes | 745 | 129 | 17.3 (14.4,20.6) |

| Continued breastfeeding rate (1 year) c | |||

| Yes | 413 | 397 | 96.2 (93.1, 97.9) |

| Continued breastfeeding rate (2 years) d | |||

| Yes | 284 | 260 | 91.4 (86.6, 94.6) |

| Early introduction of complementary feeding rate e | |||

| Yes | 361 | 234 | 64.9 (59.0, 70.4) |

| Median duration of any breastfeeding a (months) | 23.0 | ||

| Median duration of exclusive breastfeeding a (months) | 3.6 | ||

| Characteristic | Delayed Initiation of BF | BotBF | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||||||

| OR | [95% CI] | p | OR | [95% CI] | p | OR | [95% CI] | p | OR | [95% CI] | p | |||||

| Individual-level factors | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother’s religion | ||||||||||||||||

| Others $ (Islam, OR = 1) | 0.81 | 0.57 | 1.16 | 0.247 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 1.18 | 0.144 | ||||||||

| Maternal working status | ||||||||||||||||

| Working (Non-working, OR = 1) | 0.87 | 0.64 | 1.17 | 0.359 | 0.90 | 0.52 | 1.57 | 0.703 | ||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||||

| Formerly married ^ (Currently married, OR = 1) | 0.88 | 0.39 | 1.99 | 0.760 | 1.01 | 0.20 | 4.97 | 0.991 | ||||||||

| Maternal education | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary (No education, OR = 1) | 0.80 | 0.57 | 1.12 | 0.197 | 0.92 | 0.54 | 1.60 | 0.776 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 1.15 | 0.139 | ||||

| Secondary and above | 0.82 | 0.59 | 1.13 | 0.214 | 1.25 | 0.73 | 2.12 | 0.417 | 0.57 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.049 | ||||

| Partner’s education | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary (No education, OR = 1) | 0.97 | 0.71 | 1.32 | 0.826 | 0.86 | 0.48 | 1.53 | 0.606 | ||||||||

| Secondary and above | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.94 | 0.015 | 1.30 | 0.76 | 2.21 | 0.334 | ||||||||

| Husband’s occupation | ||||||||||||||||

| Agricultural (Non-agricultural, OR = 1) | 0.99 | 0.80 | 1.23 | 0.939 | 0.72 | 0.43 | 1.20 | 0.212 | ||||||||

| Not working | 0.77 | 0.58 | 1.03 | 0.080 | 0.96 | 0.63 | 1.46 | 0.851 | ||||||||

| Mother’s age | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–19 years (12–18 years, OR = 1) | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.028 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.95 | 0.014 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.37 | 0.995 | ||||

| Birth order | ||||||||||||||||

| 2nd–4th (First-born, OR = 1) | 0.99 | 0.77 | 1.27 | 0.948 | 0.66 | 0.43 | 1.01 | 0.054 | ||||||||

| Preceding birth interval | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes (No previous birth, OR = 1) | 0.98 | 0.76 | 1.26 | 0.862 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.94 | 0.024 | ||||||||

| Sex of baby | ||||||||||||||||

| Female (Male, OR = 1) | 1.09 | 0.91 | 1.32 | 0.354 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.96 | 0.026 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.96 | 0.026 | ||||

| Number of children | ||||||||||||||||

| 2–4 (I child, OR = 1) | 1.01 | 0.77 | 1.33 | 0.937 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.89 | 0.014 | ||||||||

| Age of child (months) | ||||||||||||||||

| 6–11 (0–5 months, OR = 1) | 0.93 | 0.69 | 1.24 | 0.606 | 1.31 | 0.83 | 2.05 | 0.244 | 1.30 | 0.85 | 1.99 | 0.233 | ||||

| 12–17 | 1.07 | 0.84 | 1.37 | 0.560 | 0.85 | 0.58 | 1.27 | 0.432 | 0.88 | 0.58 | 1.33 | 0.545 | ||||

| 18–23 | 0.95 | 0.72 | 1.26 | 0.730 | 0.63 | 0.40 | 0.99 | 0.047 | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 0.043 | ||||

| Combined Mode and Place of delivery | ||||||||||||||||

| Vaginal (Caesarean, OR = 1) | 0.83 | 0.64 | 1.08 | 0.163 | 1.07 | 0.79 | 1.45 | 0.683 | 1.29 | 0.83 | 2.00 | 0.257 | ||||

| Home | 1.93 | 1.42 | 2.63 | <0.001 | 2.60 | 1.86 | 3.69 | 1.93 | 1.31 | 2.85 | 0.001 | |||||

| Type of delivery assistance | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-health professional (Health professional, OR = 1) | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.98 | 0.029 | 0.62 | 0.45 | 0.86 | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Antenatal Clinic visits | ||||||||||||||||

| 4–7 (8+, OR = 1) | 1.30 | 0.82 | 2.06 | 0.259 | 1.52 | 0.96 | 2.41 | 0.076 | 0.89 | 0.41 | 1.94 | 0.763 | 0.99 | 0.46 | 2.11 | 0.978 |

| 1–3 | 1.18 | 0.75 | 1.85 | 0.482 | 1.34 | 0.85 | 2.12 | 0.204 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 1.20 | 0.150 | 0.72 | 0.36 | 1.42 | 0.341 |

| None | 1.60 | 1.00 | 2.57 | 0.050 | 1.83 | 1.13 | 2.97 | 0.014 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.58 | 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.80 | 0.011 |

| Postnatal check-up | ||||||||||||||||

| After 2 days (0–2 days, OR = 1) | 1.61 | 1.17 | 2.20 | 0.003 | 1.70 | 1.24 | 2.35 | 0.001 | 0.91 | 0.56 | 1.48 | 0.707 | ||||

| No postnatal check-up | 1.12 | 0.89 | 1.40 | 0.337 | 1.26 | 0.96 | 1.64 | 0.091 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.89 | 0.008 | ||||

| Mother’s BMI | ||||||||||||||||

| 18.5–24.9 (<18.5, OR = 1) | 1.03 | 0.65 | 1.65 | 0.885 | 0.75 | 0.41 | 1.36 | 0.336 | ||||||||

| 25+ | 1.16 | 0.71 | 1.91 | 0.548 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 0.052 | ||||||||

| Exposure to Media | ||||||||||||||||

| Mothers reading Newspapers | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes # (Not at all, OR = 1) | 1.07 | 0.80 | 1.43 | 0.661 | 1.60 | 1.10 | 2.34 | 0.014 | ||||||||

| Mothers listening to the radio | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes # (Not at all, OR = 1) | 1.28 | 1.02 | 1.60 | 0.033 | 1.30 | 0.92 | 1.83 | 0.137 | ||||||||

| Mothers watching TV | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes # (Not at all, OR = 1) | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.98 | 0.028 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.94 | 0.006 | 1.72 | 1.15 | 2.57 | 0.009 | ||||

| Household-level factors | ||||||||||||||||

| Household Wealth Index | ||||||||||||||||

| Richer (Richest, OR = 1) | 1.14 | 0.86 | 1.50 | 0.359 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 1.08 | 0.104 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 1.20 | 0.225 | ||||

| Middle | 1.07 | 0.78 | 1.45 | 0.685 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.75 | 0.001 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.90 | 0.015 | ||||

| Poorer | 1.05 | 0.80 | 1.38 | 0.729 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.64 | <0.001 | ||||

| Poorest | 1.00 | 0.72 | 1.37 | 0.976 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.39 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.44 | <0.001 | ||||

| Decisions women have a final say | ||||||||||||||||

| Some Decisions (No Decision, OR = 1) | 1.06 | 0.85 | 1.32 | 0.581 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 1.36 | 0.877 | ||||||||

| All Decisions | 0.82 | 0.65 | 1.03 | 0.081 | 0.82 | 0.54 | 1.21 | 0.313 | ||||||||

| Residence | ||||||||||||||||

| Rural (Urban, OR = 1) | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.19 | 0.700 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.86 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Geographical Region without Rangpur | ||||||||||||||||

| Chittagong (Barisal, OR = 1) | 1.03 | 0.71 | 1.48 | 0.890 | 0.84 | 0.46 | 1.53 | 0.564 | ||||||||

| Dhaka | 0.91 | 0.64 | 1.29 | 0.584 | 2.21 | 1.27 | 3.86 | 0.005 | ||||||||

| Khulna | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.98 | 0.041 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 1.35 | 0.308 | ||||||||

| Rajshahi | 0.83 | 0.59 | 1.19 | 0.310 | 1.29 | 0.71 | 2.34 | 0.401 | ||||||||

| Sylhet | 0.77 | 0.53 | 1.11 | 0.166 | 1.21 | 0.64 | 2.28 | 0.560 | ||||||||

| Geographical Region with Rangpur | ||||||||||||||||

| Chittagong (Barisal, OR = 1) | 1.03 | 0.71 | 1.48 | 0.890 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 1.63 | 0.567 | 0.84 | 0.46 | 1.53 | 0.564 | ||||

| Dhaka | 0.91 | 0.64 | 1.29 | 0.584 | 0.98 | 0.69 | 1.40 | 0.913 | 2.21 | 1.27 | 3.86 | 0.005 | ||||

| Khulna | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.98 | 0.041 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 1.08 | 0.120 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 1.35 | 0.308 | ||||

| Rajshahi | 0.83 | 0.59 | 1.19 | 0.310 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 1.12 | 0.656 | 1.29 | 0.71 | 2.34 | 0.401 | ||||

| Sylhet | 0.77 | 0.53 | 1.12 | 0.168 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 1.16 | 0.211 | 1.21 | 0.64 | 2.28 | 0.559 | ||||

| Rangpur | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.74 | 0.001 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.82 | 0.004 | 0.72 | 0.31 | 1.71 | 0.461 | ||||

| Characteristic | EBF | PBF | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||||||

| OR | [95% CI] | p | OR | [95% CI] | p | OR | [95% CI] | p | OR | [95% CI] | p | |||||

| Individual-level factors | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother’s religion | ||||||||||||||||

| Others $ (Islam, OR = 1) | 1.74 | 0.84 | 3.58 | 0.133 | 0.80 | 0.23 | 2.86 | 0.735 | ||||||||

| Maternal working status | ||||||||||||||||

| Working (Non-working, OR = 1) | 0.64 | 0.30 | 1.39 | 0.262 | 2.53 | 1.02 | 6.29 | 0.045 | ||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||||

| Formerly married ^ (Currently married, OR = 1) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Maternal education | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary (No education, OR = 1) | 0.70 | 0.37 | 1.32 | 0.263 | 1.07 | 0.46 | 2.48 | 0.876 | ||||||||

| Secondary and above | 0.76 | 0.44 | 1.31 | 0.326 | 1.74 | 0.80 | 3.78 | 0.160 | ||||||||

| Partner’s education | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary (No education, OR = 1) | 1.24 | 0.78 | 1.97 | 0.360 | 0.87 | 0.50 | 1.51 | 0.615 | ||||||||

| Secondary and above | 1.48 | 0.92 | 2.38 | 0.102 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 1.50 | 0.566 | ||||||||

| Husband’s occupation | ||||||||||||||||

| Agricultural (Non-agricultural, OR = 1) | 0.98 | 0.64 | 1.50 | 0.921 | 1.37 | 0.80 | 2.35 | 0.252 | ||||||||

| Not working | 1.13 | 0.64 | 2.00 | 0.669 | 1.09 | 0.58 | 2.05 | 0.791 | ||||||||

| Mother’s age | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–19 years (12–18 years, OR = 1) | 1.30 | 0.89 | 1.88 | 0.170 | 1.07 | 0.70 | 1.64 | 0.758 | ||||||||

| Birth order | ||||||||||||||||

| 2nd–4th (First-born, OR = 1) | 1.38 | 0.89 | 2.15 | 0.149 | 0.82 | 0.49 | 1.36 | 0.439 | ||||||||

| Preceding birth interval | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes (No previous birth, OR = 1) | 1.38 | 0.89 | 2.15 | 0.149 | 0.82 | 0.49 | 1.36 | 0.439 | ||||||||

| Sex of baby | ||||||||||||||||

| Female (Male, OR = 1) | 1.23 | 0.85 | 1.79 | 0.278 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 1.05 | 0.082 | ||||||||

| Number of children | ||||||||||||||||

| 2–4 (1 child, OR = 1) | 1.62 | 1.02 | 2.59 | 0.041 | 1.72 | 1.00 | 2.97 | 0.050 | 0.72 | 0.41 | 1.26 | 0.254 | ||||

| Age of child (months) | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.65 | <0.001 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.62 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.33 | 0.018 | 1.16 | 1.02 | 1.315 | 0.029 |

| Combined Mode and Place of delivery | ||||||||||||||||

| Vaginal (Caesarean, OR = 1) | 1.47 | 0.88 | 2.43 | 0.139 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 1.02 | 0.058 | ||||||||

| Home | 1.08 | 0.64 | 1.81 | 0.784 | 0.70 | 0.36 | 1.35 | 0.286 | ||||||||

| Type of delivery assistance | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-health professional (Health professional, OR = 1) | 0.76 | 0.50 | 1.14 | 0.183 | 1.53 | 0.91 | 2.58 | 0.108 | ||||||||

| Antenatal Clinic visits | ||||||||||||||||

| 4–7 (8+, OR = 1) | 0.67 | 0.18 | 2.41 | 0.537 | 1.49 | 0.41 | 5.51 | 0.545 | ||||||||

| 1–3 | 0.51 | 0.16 | 1.64 | 0.257 | 1.20 | 0.34 | 4.26 | 0.781 | ||||||||

| None | 0.58 | 0.18 | 1.89 | 0.366 | 1.96 | 0.53 | 7.23 | 0.310 | ||||||||

| Postnatal check-up | ||||||||||||||||

| After 2 days (0–2 days, OR = 1) | 1.13 | 0.51 | 2.54 | 0.761 | 1.37 | 1.21 | 4.65 | 0.012 | 0.69 | 0.32 | 1.48 | 0.337 | ||||

| No postnatal check-up | 0.80 | 0.33 | 1.92 | 0.619 | 1.20 | 0.78 | 1.91 | 0.430 | 1.02 | 0.64 | 1.64 | 0.919 | ||||

| Mother’s BMI | ||||||||||||||||

| 18.5–24.9 (<18.5, OR = 1) | 1.13 | 0.51 | 2.54 | 0.761 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 2.71 | 0.998 | ||||||||

| 25+ | 0.80 | 0.33 | 1.92 | 0.619 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 2.82 | 0.959 | ||||||||

| Exposure to Media | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother reading Newspapers | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes # (Not at all, OR = 1) | 0.81 | 0.52 | 1.28 | 0.367 | 1.43 | 0.83 | 2.48 | 0.196 | ||||||||

| Mother listening to the radio | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes # (Not at all, OR = 1) | 0.71 | 0.47 | 1.07 | 0.100 | 1.61 | 1.02 | 2.54 | 0.040 | 1.71 | 1.07 | 2.73 | 0.024 | ||||

| Mother watching television | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes # (Not at all, OR = 1) | 0.83 | 0.57 | 1.21 | 0.336 | 1.15 | 0.74 | 1.77 | 0.531 | ||||||||

| Household-level factors | ||||||||||||||||

| Household Wealth Index | ||||||||||||||||

| Richer (Richest, OR = 1) | 1.15 | 0.70 | 1.89 | 0.573 | 0.95 | 0.51 | 1.75 | 0.865 | ||||||||

| Middle | 1.25 | 0.72 | 2.18 | 0.428 | 0.76 | 0.36 | 1.58 | 0.459 | ||||||||

| Poorer | 1.11 | 0.65 | 1.90 | 0.696 | 0.92 | 0.47 | 1.78 | 0.796 | ||||||||

| Poorest | 1.29 | 0.67 | 2.48 | 0.450 | 0.63 | 0.30 | 1.29 | 0.206 | ||||||||

| Decision-marking (Autonomy) | ||||||||||||||||

| Some Decisions (No Decision, OR = 1) | 0.67 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 0.055 | 1.43 | 0.89 | 2,28 | 0.137 | ||||||||

| All Decisions | 0.79 | 0.47 | 1.34 | 0.392 | 0.88 | 0.48 | 1.63 | 0.693 | ||||||||

| Residence | ||||||||||||||||

| Rural (Urban, OR = 1) | 1.25 | 0.85 | 1.85 | 0.258 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 1.64 | 0.989 | ||||||||

| Geographical Region without Rangpur | ||||||||||||||||

| Chittagong (Barisal, OR = 1) | 3.14 | 1.70 | 5.82 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.93 | 0.030 | ||||||||

| Dhaka | 1.53 | 0.83 | 2.82 | 0.171 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| Khulna | 3.10 | 1.66 | 5.78 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.25 | 1.10 | 0.089 | ||||||||

| Rajshahi | 1.42 | 0.78 | 2.59 | 0.254 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.015 | ||||||||

| Sylhet | 4.13 | 2.00 | 8.56 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.26 | 1.29 | 0.178 | ||||||||

| Geographical Region with Rangpur | ||||||||||||||||

| Chittagong (Barisal, OR = 1) | 3.14 | 1.70 | 5.82 | <0.001 | 3.19 | 1.59 | 6.41 | 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.93 | 0.030 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 0.92 | 0.029 |

| Dhaka | 1.53 | 0.83 | 2.82 | 0.171 | 1.33 | 0.71 | 2.50 | 0.372 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.002 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.64 | 0.002 |

| Khulna | 3.10 | 1.66 | 5.78 | <0.001 | 3.62 | 1.80 | 7.29 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.25 | 1.10 | 0.089 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 1.03 | 0.061 |

| Rajshahi | 1.42 | 0.78 | 2.59 | 0.254 | 1.34 | 0.69 | 2.62 | 0.389 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.015 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.80 | 0.011 |

| Sylhet | 4.13 | 1.97 | 8.65 | <0.001 | 5.11 | 2.24 | 11.63 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.26 | 1.30 | 0.184 | 0.57 | 0.25 | 1.28 | 0.173 |

| Rangpur | 6.42 | 2.71 | 15.22 | <0.001 | 6.10 | 2.20 | 16.86 | 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.002 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.58 | 0.003 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agho, K.E.; Ahmed, T.; Fleming, C.; Dhami, M.V.; Miner, C.A.; Torome, R.; Ogbo, F.A.; on behalf of the Global Maternal and Child Health Research Collaboration (GloMACH). Breastfeeding Practices among Adolescent Mothers and Associated Factors in Bangladesh (2004–2014). Nutrients 2021, 13, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020557

Agho KE, Ahmed T, Fleming C, Dhami MV, Miner CA, Torome R, Ogbo FA, on behalf of the Global Maternal and Child Health Research Collaboration (GloMACH). Breastfeeding Practices among Adolescent Mothers and Associated Factors in Bangladesh (2004–2014). Nutrients. 2021; 13(2):557. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020557

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgho, Kingsley Emwinyore, Tahmeed Ahmed, Catharine Fleming, Mansi Vijaybhai Dhami, Chundung Asabe Miner, Raphael Torome, Felix Akpojene Ogbo, and on behalf of the Global Maternal and Child Health Research Collaboration (GloMACH). 2021. "Breastfeeding Practices among Adolescent Mothers and Associated Factors in Bangladesh (2004–2014)" Nutrients 13, no. 2: 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020557

APA StyleAgho, K. E., Ahmed, T., Fleming, C., Dhami, M. V., Miner, C. A., Torome, R., Ogbo, F. A., & on behalf of the Global Maternal and Child Health Research Collaboration (GloMACH). (2021). Breastfeeding Practices among Adolescent Mothers and Associated Factors in Bangladesh (2004–2014). Nutrients, 13(2), 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020557