Adequacy and Sources of Protein Intake among Pregnant Women in the United States, NHANES 2003–2012

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Population Characteristics

2.3. Dietary Intake Data

2.4. Assessment of Protein Intake and Adequacy

2.5. Identification of Protein by Source

2.6. Assessment of Protein Adequacy Using Alternate Requirements

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

3.2. Intake of Protein and Adequacy of Intake

3.3. Intake of Protein by Source

3.4. Animal Protein and Protein Requirements

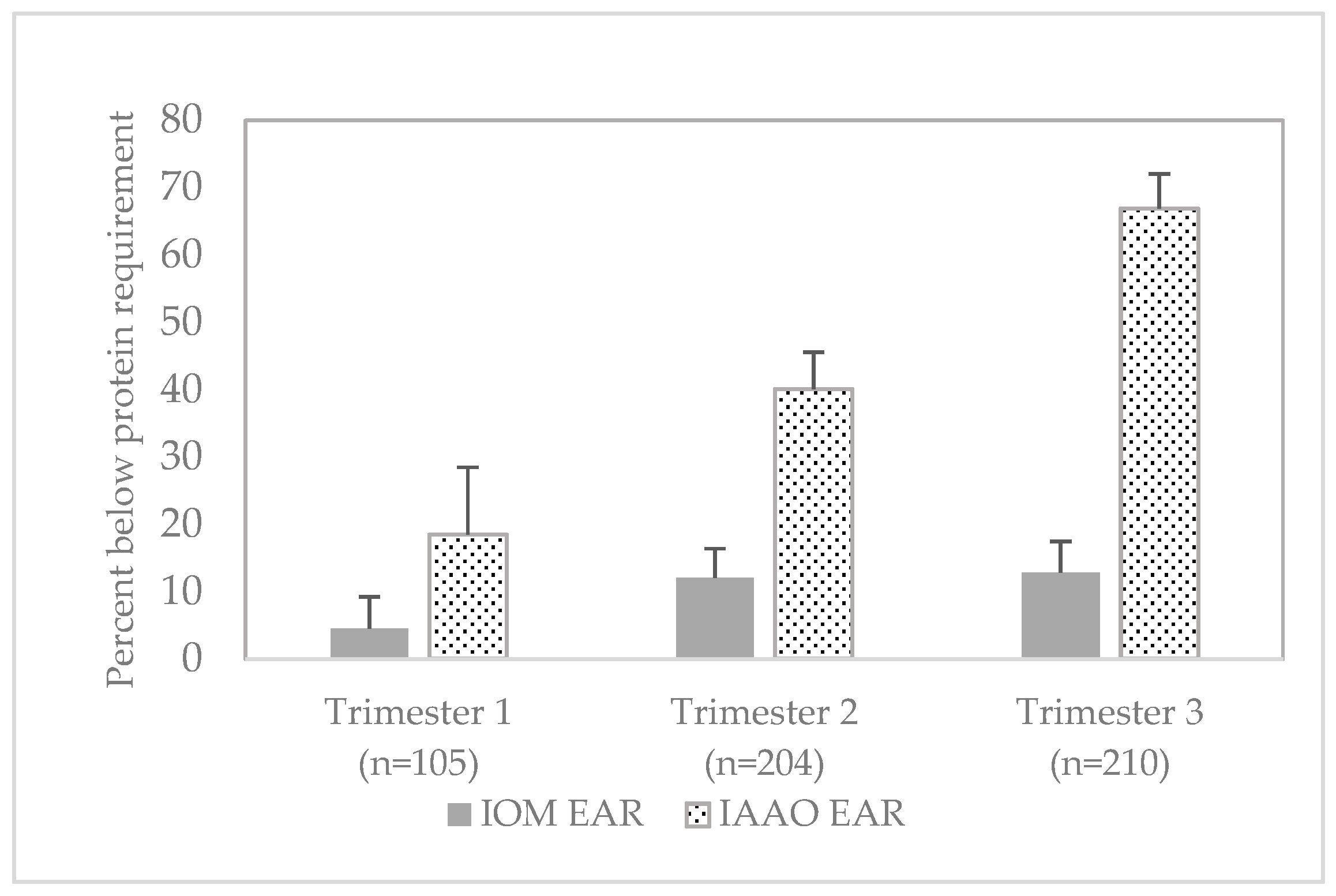

3.5. Adequacy of Protein Intake Based on Alternate Requirements

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Procter, S.B.; Campbell, C.G. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Nutrition and lifestyle for a healthy pregnancy outcome. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2014, 114, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picciano, M.F. Pregnancy and lactation: Physiological adjustments, nutritional requirements and the role of dietary supplements. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1997S–2002S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrates, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein and Amino Acids; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for protein. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Baerlocher, K.; Bauer, J.M.; Elmadfa, I.; Heseker, H.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Stangl, G.; Vokert, D.; Stehle, P. Revised Reference Values for the Intake of Protein. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elango, R.; Ball, R.O. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements during Pregnancy. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 839S–844S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stephens, T.V.; Payne, M.; Ball, R.O.; Pencharz, P.B.; Elango, R. Protein requirements of healthy pregnant women during early and late gestation are higher than current recommendations. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bailey, R.L.; Pac, S.G.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Reidy, K.C.; Catalano, P.M. Estimation of Total Usual Dietary Intakes of Pregnant Women in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e195967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service. Protein (g/day): Mean Intake and Percentiles of Usual Intake from Food and Beverages by Dietary Reference Intake Age-Gender Groups in the United States, Females 19–50, 2007–2010. 2014. Available online: https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015/advisory-report/appendix-e-2/appendix-e-24#protein (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Berryman, C.E.; Lieberman, H.R.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Pasiakos, S.M. Protein intake trends and conformity with the Dietary Reference Intakes in the United States: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2014. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd. Current protein intake in America: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2004. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1554S–1557S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Ahluwalia, N.; Dwyer, J.; Terry, A.; Moshfegh, A.; Johnson, C. Update on NHANES Dietary Data: Focus on Collection, Release, Analytical Considerations, and Uses to Inform Public Policy. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Institute of Medicine. Weight Gain during Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service. Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fndds-download-databases/ (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Moshfegh, A.; Goldman, J.; Cleveland, L. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2001–2002: Usual Nutrient Intakes from Food Compared to Dietary Reference Intakes. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2005. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/0102/usualintaketables2001-02.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service. Usual Nutrient Intakes, WWEIA NHANES 2015–2018. 2021. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/usual/Usual_Intake_gender_WWEIA_2015_2018.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Legacy Release. Available online: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/usda-national-nutrient-database-standard-reference-legacy-release (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service. Food Patterns Equivalents Database. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fped-databases/ (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Tooze, J.A.; Kipnis, V.; Buckman, D.W.; Carroll, R.J.; Freedman, L.S.; Guenther, P.M.; Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Subar, A.F.; Dodd, K.W. A mixed-effects model approach for estimating the distribution of usual intake of nutrients: The NCI method. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 2857–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Herrick, K.A.; Rossen, L.M.; Parsons, R.; Dodd, K.W. Estimating Usual Dietary in Take from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data Using the National Cancer Institute Method. Vital Health Stat. 2018, 2, 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: Applications in Dietary Assessment; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, L.S.; Guenther, P.M.; Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Kott, P.S. A population’s mean Healthy Eating Index-2005 scores are best estimated by the score of the population ratio when one 24-hour recall is available. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 1725–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Analytic and Reporting Guidelines: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES III (1988–94). Hyattsville, MD. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1996. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/analyticguidelines/88-94-analytic-reporting-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service. WWEIA Data Tables. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/wweia-data-tables/ (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Hoy, M.K.; Clemens, J.C.; Moshfegh, A. Protein Intake of Adults in the U.S.: What We Eat in America, NHANES 2015–2016. Food Surveys Research Group Dietary Data Brief No. 29. January 2021, Revised Slightly from July 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/DBrief/29_Protein_Intake_of_Adults_1516.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th Edition. 2020. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Millward, D.J.; Jackson, A.A. Protein requirements and the indicator amino acid oxidation method. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1498–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fukagawa, N.K. Protein requirements: Methodologic controversy amid a call for change. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 761–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matthews, D.E. Can We Define Dietary Requirements of Dispensable Amino Acids? J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Total with Trimester of Pregnancy 1 (n = 528) | Trimester 1 (n = 109) | Trimester 2 (n = 207) | Trimester 3 (n = 212) | Missing Trimester 2 (n = 75) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.7 ± 0.44 | 27.9 ± 0.61 | 28.3 ± 0.69 | 29.6 ± 0.74 | 28.3 ± 1.07 |

| Age (%) | |||||

| 20–30 years | 62.4 ± 3.76 | 75.0 ± 6.34 | 62.7 ± 5.64 | 53.6 ± 6.8 | 66.9 ± 7.53 |

| 31–44 years | 37.6 ± 3.76 | 25.0 ± 6.34 | 37.3 ± 5.64 | 46.4 ± 6.8 | 33.1 ± 7.53 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |||||

| Mexican American/ Other Hispanic | 23.1 ± 3.26 | 24.2 ± 7.06 | 22.2 ± 4.76 | 23.2 ± 3.91 | 18.0 ± 6.08 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 52.9 ± 4.25 | 58.6 ± 8.86 | 47.3 ± 5.87 | 53.7 ± 5.84 | 46.3 ± 9.38 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13.5 ± 2.68 | 8.7 ± 3.69 | 20.9 ± 4.41 | 10.6 ± 3.15 | 29.6 ± 7.46 |

| Other race | 10.5 ± 2.52 | 8.6 ± 4.13 | 9.7 ± 3.92 | 12.5 ± 4.15 | 6.1 ± 3.79 |

| Poverty income ratio (PIR, %) | |||||

| <1.85 | 34.6 ± 3.92 | 32.6 ± 8.73 | 38.3 ± 5.49 | 32.8 ± 5.36 | 39.5 ± 8.58 |

| ≥1.85 | 65.4 ± 3.92 | 67.4 ± 8.73 | 61.7 ± 5.49 | 67.2 ± 5.36 | 60.5 ± 8.58 |

| Education status (%) | |||||

| <High school | 19.9 ± 2.47 | 14.1 ± 3.94 | 23.4 ± 5.28 | 20.8 ± 4.70 | 19.5 ± 6.83 |

| High school diploma | 13.7 ± 1.93 | 9.7 ± 3.19 | 15.1 ± 3.68 | 15.4 ± 3.28 | 34.9 ± 9.02 |

| Some college | 33.2 ± 3.34 | 47.7 ± 8.15 | 29.7 ± 4.69 | 26.3 ± 5.25 | 21.5 ± 5.8 |

| Undergraduate degree or higher | 33.2 ± 3.36 | 28.5 ± 7.18 | 31.9 ± 5.55 | 37.5 ± 6.39 | 24.0 ± 7.6 |

| Parity (%) | |||||

| 0 | 25.6 ± 3.55 | 31.7 ± 7.94 | 30.0 ± 5.53 | 18.3 ± 2.97 | 38.4 ± 12.74 |

| 1 | 43.5 ± 3.82 | 40.4 ± 7.10 | 51.8 ± 6.67 | 38.8 ± 6.10 | 25.5 ± 11.71 |

| ≥2 | 30.9 ± 3.20 | 27.9 ± 5.78 | 18.2 ± 3.24 | 42.9 ± 5.62 | 36.1 ± 10.85 |

| Marital status (%) | |||||

| Married | 69.3 ± 3.06 | 68.6 ± 6.74 | 68.9 ± 5.29 | 70.2 ± 5.00 | 49.1 ± 9.13 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 2.3 ± 0.69 | 3.7 ± 1.84 | 1.0 ± 0.43 | 2.3 ± 1.25 | 3.1 ± 1.39 |

| Never married | 28.4 ± 3.1 | 27.7 ± 6.62 | 30.1 ± 5.12 | 27.5 ± 4.98 | 47.8 ± 8.84 |

| Physical activity, minutes/week (%) | |||||

| <10 | 31.7 ± 3.44 | 24.9 ± 6.41 | 34.4 ± 5.82 | 34.1 ± 5.86 | 51.2 ± 8.93 |

| 10 to <150 | 30.1 ± 3.57 | 35.2 ± 6.83 | 29.1 ± 4.97 | 27.5 ± 5.38 | 19.7 ± 4.51 |

| ≥150 | 38.2 ± 3.94 | 39.9 ± 7.26 | 36.5 ± 5.76 | 38.4 ± 6.74 | 29.1 ± 9.17 |

| Smoking status (%) | |||||

| Never smoked | 69.3 ± 3.53 | 69.5 ± 6.73 | 65.5 ± 6.33 | 72.4 ± 5.16 | 69.4 ± 8.92 |

| Past smoker | 23.3 ± 3.46 | 21.3 ± 6.15 | 26.7 ± 5.94 | 21.7 ± 4.72 | 17.4 ± 8.27 |

| Current smoker | 7.4 ± 1.48 | 9.2 ± 3.04 | 7.7 ± 3.25 | 6.0 ± 2.67 | 13.2 ± 5.87 |

| Dietary supplement use (%) | 85.6 ± 2.11 | 75.7 ± 5.76 | 88.6 ± 3.35 | 89.7 ± 3.79 | 43.8 ± 8.29 |

| Pre-pregnancy body weight (kg) | 70.7 ± 1.37 | 74.0 ± 3.03 | 72.6 ± 2.76 | 68.0 ± 1.97 | - |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 26.8 ± 0.5 | 27.6 ± 1.0 | 27.7 ± 0.93 | 25.6 ± 0.79 | - |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI status (%) | |||||

| Underweight | 5.2 ± 1.7 | 4.1 ± 3.45 | 5.8 ± 2.41 | 5.4 ± 3.27 | - |

| Normal weight | 46.7 ± 3.57 | 40.6 ± 8.21 | 39.3 ± 5.31 | 57.0 ± 5.68 | - |

| Overweight | 21.8 ± 2.91 | 16.3 ± 6.07 | 25.7 ± 5.67 | 22.0 ± 4.16 | - |

| Obese | 26.3 ± 3.35 | 39.0 ± 8.11 | 29.1 ± 4.86 | 15.7 ± 3.56 | - |

| GWG status (%) | |||||

| Inadequate | 19.7 ± 2.87 | 35.8 ± 8.47 | 16.0 ± 3.78 | 12.2 ± 3.63 | - |

| Adequate | 31.5 ± 3.87 | 30.8 ± 8.45 | 30.4 ± 5.86 | 32.8 ± 6.62 | - |

| Excess | 48.9 ± 3.75 | 33.3 ± 7.47 | 53.6 ± 6.24 | 55.1 ± 6.73 | - |

| Trimester of Pregnancy | Percentile | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | |

| grams protein per day (g/day) | ||||||||

| Total (n = 528) | 84 ± 2.3 | 57 ± 3.8 | 62 ± 3.3 | 71 ± 2.7 | 83 ± 2.3 | 95 ± 2.9 | 107 ± 4.2 | 115 ± 5.2 |

| 1 (n = 109) | 88 ± 4.3 | 61 ± 5.4 1 | 66 ± 5.2 1 | 75 ± 4.8 | 87 ± 4.4 | 100 ± 4.7 | 112 ± 5.51 | 120 ± 6.3 1 |

| 2 (n = 207) | 82 ± 3.1 | 55 ± 4.0 | 60 ± 3.6 | 70 ± 3.2 | 80 ± 3.0 | 92 ± 3.8 | 104 ± 5.1 | 111 ± 6.0 |

| 3 (n = 212) | 82 ± 2.9 | 56 ± 4.1 | 61 ± 3.7 | 70 ± 3.2 | 82 ± 2.9 | 94 ± 3.5 | 105 ± 4.9 | 112 ± 5.9 |

| grams protein per kilogram body weight (g/kg bw/day) 2 | ||||||||

| Total (n = 519) | 1.34 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.10 | 0.82 ± 0.09 | 1.04 ± 0.07 | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 1.61 ± 0.05 | 1.88 ± 0.08 | 2.06 ± 0.10 |

| 1 (n = 105) | 1.30 ± 0.10 | 0.68 ± 0.15 1 | 0.79 ± 0.14 1 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 1.27 ± 0.11 | 1.57 ± 0.09 | 1.84 ± 0.09 1 | 2.03 ± 0.09 1 |

| 2 (n = 204) | 1.35 ± 0.06 | 0.71 ± 0.09 | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 1.32 ± 0.05 | 1.61 ± 0.08 | 1.90 ± 0.11 | 2.07 ± 0.13 |

| 3 (n = 210) | 1.35 ± 0.05 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 1.05 ± 0.06 | 1.33 ± 0.05 | 1.62 ± 0.07 | 1.89 ± 0.11 | 2.07 ± 0.13 |

| Protein Intake | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n1 | g/day | g/kg bw/day 2 |

| Total with Trimester of Pregnancy | 528/519 | 84 ± 1.9 | 1.31 ± 03 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–30 | 356/348 | 86 ± 2.3 | 1.41 ± 0.04 |

| 31–44 | 172/171 | 82 ± 2.7 | 1.32 ± 0.04 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Mexican American/Other Hispanic | 180/175 | 87 ± 3.4 | 1.45 ± 0.06 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 239/237 | 81 ± 3.0 | 1.28 ± 0.05 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 72/70 | 86 ± 4.0 | 1.41 ± 0.08 |

| Poverty income ratio (PIR) | |||

| <1.85 | 222/218 | 86 ± 2.8 | 1.42 ± 0.04 |

| ≥1.85 | 279/275 | 83 ± 2.6 | 1.35 ± 0.04 |

| Education status | |||

| <High school | 136/135 | 82 ± 3.5 | 1.37 ± 0.06 |

| High school diploma | 96/92 | 88 ± 5.2 | 1.51 ± 0.11 |

| Some college | 156/153 | 83 ± 3.6 | 1.32 ± 0.07 |

| Undergraduate degree or higher | 140/139 | 86 ± 3.3 | 1.38 ± 0.05 |

| Protein Source | Total (n = 528) | Trimester 1 (n = 109) | Trimester 2 (n = 207) | Trimester 3 (n = 212) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Protein | |||||

| Animal | Total | 66.2 ± 0.9 | 69.1 ± 1.3 | 64.9 ± 1.8 | 65.3 ± 1.1 |

| Total red meat 1 | 15.5 ± 1.2 | 18.2 ± 2.7 | 11.7 ± 1.3 | 16.6 ± 1.9 | |

| Beef | 12.7 ± 1.1 | 14.8 ± 2.7 | 10 ± 1.1 | 13.3 ± 1.7 | |

| Pork | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.9 | |

| Poultry | 13.2 ± 1.1 | 12.6 ± 2.2 | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 13.1 ± 1.8 | |

| Cured meat and poultry | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 6.5 ± 1.0 | 5.8 ± 1.0 | |

| Dairy | 23.1 ± 0.8 | 22.7 ± 1.6 | 25.2 ± 1.5 | 21.7 ± 1.1 | |

| Egg | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | |

| Seafood | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 1.9 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 4.1 ± 1.0 | |

| Plant | Total | 33.8 ± 0.9 | 30.9 ± 1.3 | 35.1 ± 1.8 | 34.7 ± 1.1 |

| Characteristic | n | % of Protein by Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal | Plant | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–30 | 356 | 67.4 ± 1.0 | 32.6 ± 1.0 |

| 31–44 | 172 | 64.2 ± 1.4 | 35.8 ± 1.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Mexican American/Other Hispanic | 180 | 67.9 ± 1.0 | 32.1 ± 1.0 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 239 | 65.3 ± 1.4 | 34.7 ± 1.4 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 72 | 70.6 ± 1.2 | 29.4 ± 1.2 |

| Poverty income ratio (PIR) | |||

| <1.85 | 222 | 69.5 ± 1.5 | 30.5 ± 1.5 |

| ≥1.85 | 279 | 64.6 ± 1.2 | 35.4 ± 1.2 |

| Education status | |||

| <High school | 136 | 68.7 ± 1.2 | 31.3 ± 1.2 |

| High school diploma | 96 | 70.8 ± 1.4 | 29.2 ± 1.4 |

| Some college | 156 | 67.1 ± 1.7 | 32.9 ± 1.7 |

| Undergraduate degree or higher | 140 | 62.1 ± 1.5 | 37.9 ± 1.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murphy, M.M.; Higgins, K.A.; Bi, X.; Barraj, L.M. Adequacy and Sources of Protein Intake among Pregnant Women in the United States, NHANES 2003–2012. Nutrients 2021, 13, 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030795

Murphy MM, Higgins KA, Bi X, Barraj LM. Adequacy and Sources of Protein Intake among Pregnant Women in the United States, NHANES 2003–2012. Nutrients. 2021; 13(3):795. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030795

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurphy, Mary M., Kelly A. Higgins, Xiaoyu Bi, and Leila M. Barraj. 2021. "Adequacy and Sources of Protein Intake among Pregnant Women in the United States, NHANES 2003–2012" Nutrients 13, no. 3: 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030795