Coffee Consumption and Prostate Cancer Risk: Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010 and Mendelian Randomization Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population in NHANES

2.2. Coffee Consumption Assessment in NHANES

2.3. Covariates Used in NHANES

2.4. Genetic Instruments for Coffee Consumption

2.5. Genetic Summary Data of Prostate Cancer

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Coffee Intake and Prostate Cancer Risk in NHANES

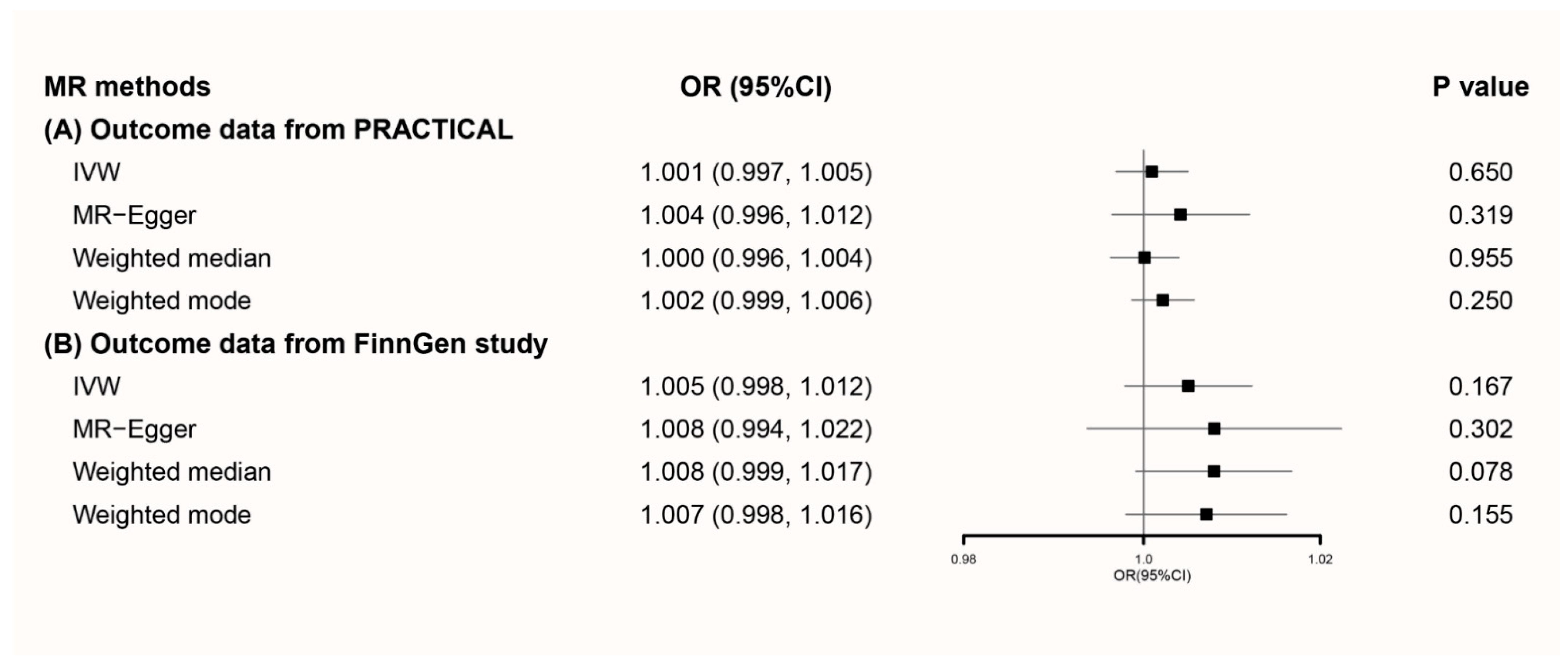

3.2. MR Analyses Using Primary Genetic Instruments

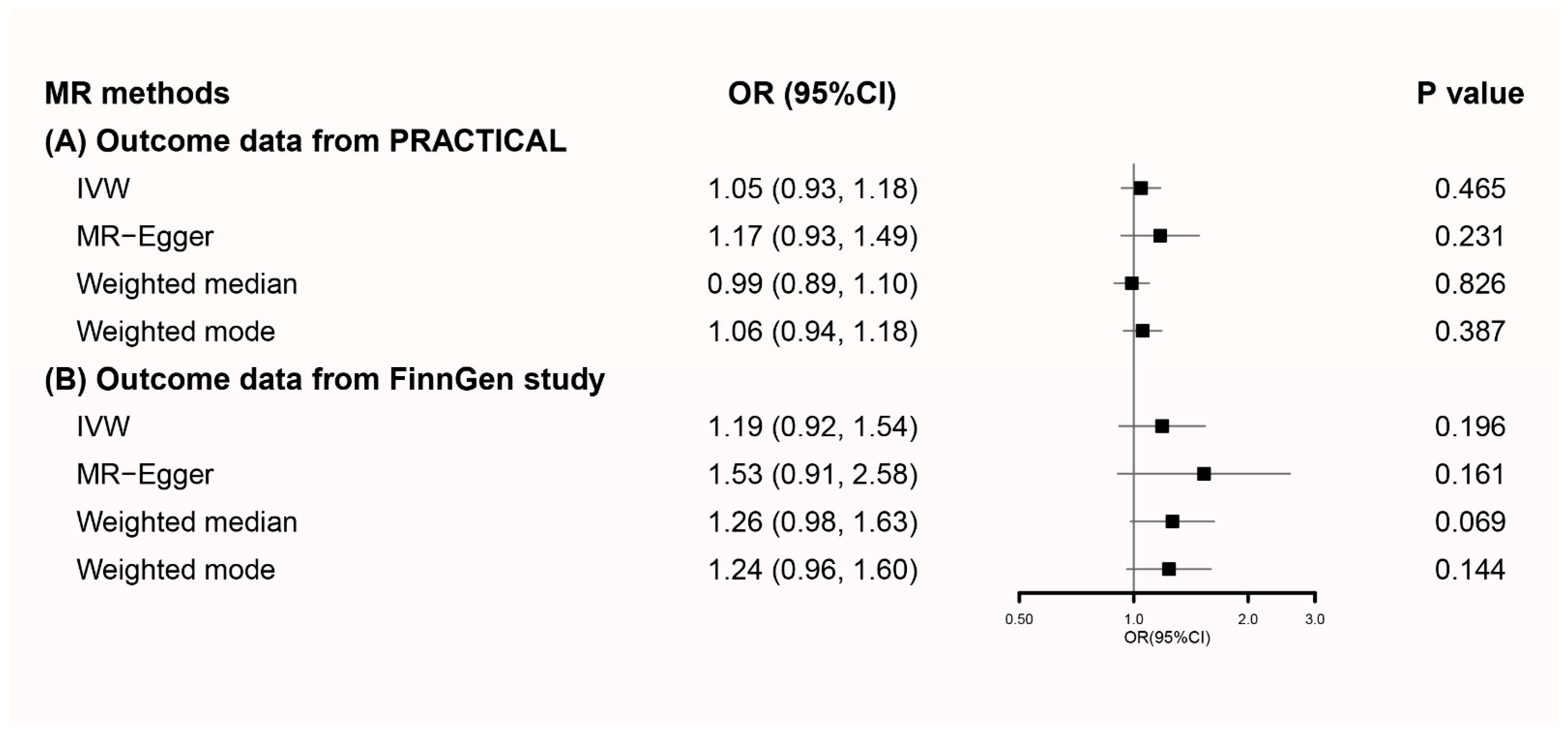

3.3. MR Analyses Using Secondary Genetic Instruments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campos, C.; Sotomayor, P.; Jerez, D.; Gonzalez, J.; Schmidt, C.B.; Schmidt, K.; Banzer, W.; Godoy, A.S. Exercise and prostate cancer: From basic science to clinical applications. Prostate 2018, 78, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzick, J.; Thorat, M.A.; Andriole, G.; Brawley, O.W.; Brown, P.H.; Culig, Z.; Eeles, R.A.; Ford, L.G.; Hamdy, F.C.; Holmberg, L.; et al. Prevention and early detection of prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e484–e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Fujita, K.; Nonomura, N. Influence of Diet and Nutrition on Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.S.; Sultan, M.T. Coffee and its consumption: Benefits and risks. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, R.M.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C. Coffee, Caffeine, and Health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kakizaki, M.; Sugawara, Y.; Tomata, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Nishino, Y.; Tsuji, I. Coffee consumption and the risk of prostate cancer: The Ohsaki Cohort Study. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pounis, G.; Tabolacci, C.; Costanzo, S.; Cordella, M.; Bonaccio, M.; Rago, L.; D’Arcangelo, D.; Filippo Di Castelnuovo, A.; de Gaetano, G.; Donati, M.B.; et al. Reduction by coffee consumption of prostate cancer risk: Evidence from the Moli-sani cohort and cellular models. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, F.P.; Borges, M.C.; Horta, B.L.; Bowden, J.; Davey Smith, G. Inflammatory Biomarkers and Risk of Schizophrenia: A 2-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, N.; Dwyer, J.; Terry, A.; Moshfegh, A.; Johnson, C. Update on NHANES Dietary Data: Focus on Collection, Release, Analytical Considerations, and Uses to Inform Public Policy. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.Y.; Papp, J.C.; Sobel, E.M.; Zhang, Z.F. Mendelian Randomization Study: The Association Between Metabolic Pathways and Colorectal Cancer Risk. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kho, P.F.; Glubb, D.M.; Thompson, D.J.; Spurdle, A.B.; O’Mara, T.A. Assessing the Role of Selenium in Endometrial Cancer Risk: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.E.; Martin, R.M.; Geybels, M.S.; Stanford, J.L.; Shui, I.; Eeles, R.; Easton, D.; Kote-Jarai, Z.; Amin Al Olama, A.; Benlloch, S.; et al. Investigating the possible causal role of coffee consumption with prostate cancer risk and progression using Mendelian randomization analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/nea/bhnrc/fsrg (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Xiao, Q.; Sinha, R.; Graubard, B.I.; Freedman, N.D. Inverse associations of total and decaffeinated coffee with liver enzyme levels in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010. Hepatology 2014, 60, 2091–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, A.; Papadimitriou, N.; Lagiou, P.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J.; Murphy, N.; Gunter, M.; Freisling, H.; Tzoulaki, I.; et al. Coffee and tea consumption and risk of prostate cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attar-Bashi, N.M.; Frauman, A.G.; Sinclair, A.J. Alpha-linolenic acid and the risk of prostate cancer. What is the evidence? J. Urol. 2004, 171, 1402–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, V.W.; Kuang, A.; Danning, R.D.; Kraft, P.; van Dam, R.M.; Chasman, D.I.; Cornelis, M.C. A genome-wide association study of bitter and sweet beverage consumption. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 2449–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffee and Caffeine Genetics Consortium; Cornelis, M.C.; Byrne, E.M.; Esko, T.; Nalls, M.A.; Ganna, A.; Paynter, N.; Monda, K.L.; Amin, N.; Fischer, K.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies six novel loci associated with habitual coffee consumption. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, F.R.; Al Olama, A.A.; Berndt, S.I.; Benlloch, S.; Ahmed, M.; Saunders, E.J.; Dadaev, T.; Leongamornlert, D.; Anokian, E.; Cieza-Borrella, C.; et al. Association analyses of more than 140,000 men identify 63 new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FinnGen. FinnGen Documentation of R4 Release. 2020. Available online: https://finngen.gitbook.io/documentation/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Nicolopoulos, K.; Mulugeta, A.; Zhou, A.; Hypponen, E. Association between habitual coffee consumption and multiple disease outcomes: A Mendelian randomisation phenome-wide association study in the UK Biobank. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3467–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Ye, D.; Huang, H.; Wu, D.J.H.; Zhuang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Mao, Y. Coffee Consumption and Risk of Stroke: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Ann. Neurol. 2020, 87, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, R.; Kennedy, O.J.; Roderick, P.; Fallowfield, J.A.; Hayes, P.C.; Parkes, J. Coffee consumption and health: Umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ 2017, 359, j5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Wei, W.; Wang, G.; Zhou, H.; Fu, Y.; Liu, N. Circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of prostate cancer: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2018, 14, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Dimou, N.L.; Al-Dabhani, K.; Lewis, S.J.; Martin, R.M.; Haycock, P.C.; Gunter, M.J.; Key, T.J.; Eeles, R.A.; Muir, K.; et al. Circulating vitamin D concentrations and risk of breast and prostate cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Pluchinotta, F.R.; Marventano, S.; Buscemi, S.; Li Volti, G.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Coffee components and cardiovascular risk: Beneficial and detrimental effects. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.Z.; Fuller, M.; Grim, M.D. Physiochemical Characteristics of Hot and Cold Brew Coffee Chemistry: The Effects of Roast Level and Brewing Temperature on Compound Extraction. Foods 2020, 9, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coffee, Cup a/Day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | <1 | 1−<2 | 2−<4 | 4+ | |

| Unweighted N | 2611 | 1598 | 1879 | 1725 | 523 |

| Age [years, Median (IQR)] | 50 (43−60) | 55 (47−67) | 57 (48−68) | 54 (47−64) | 53 (47−61) |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |||||

| Mexican American | 6.0 | 10.3 | 6.4 | 3.7 | 2.4 |

| Other Hispanic | 3.3 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 70.4 | 64.0 | 78.5 | 88.1 | 93.3 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 16.3 | 11.1 | 7.7 | 3.3 | 2.5 |

| Other race, including multi-racial | 4.0 | 6.7 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 0.8 |

| Education level (%) | |||||

| Less than 9th grade | 6.5 | 12.8 | 8.1 | 5.1 | 5.6 |

| 9–11th grade | 13.5 | 12.8 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 13.1 |

| High school graduate/GED or equivalent | 25.7 | 21.2 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 30.1 |

| Some college or AA degree | 24.3 | 27.3 | 23.7 | 29.6 | 28.7 |

| College graduate or above | 30.0 | 25.9 | 33.6 | 31.6 | 22.4 |

| Smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life (%) | |||||

| Yes | 45.4 | 60.4 | 62.0 | 69.3 | 80.4 |

| No | 54.6 | 39.6 | 38.0 | 30.7 | 19.6 |

| Overweight/obese (≥25 kg/m2) (%) | |||||

| Yes | 76.2 | 77.2 | 75.6 | 80.0 | 74.9 |

| No | 23.8 | 22.8 | 24.4 | 20.1 | 25.1 |

| Hypertension (%) | |||||

| Yes | 33.4 | 44.9 | 39.5 | 35.9 | 31.0 |

| No | 66.6 | 55.1 | 60.5 | 64.1 | 69.0 |

| Diabetes (%) | |||||

| Yes | 11.7 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 8.4 | 9.3 |

| No | 86.2 | 84.6 | 85.6 | 89.0 | 89.5 |

| Borderline | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Daily intake [Median (IQR)] | |||||

| Total energy (kcal) | 2317.0 (1823.5−3005.9) | 2069.0 (1589.5−2685.5) | 2169.0 (1730.5−2722.0) | 2328.0 (1798.0−2934.4) | 2327.8 (1808.0−2998.0) |

| Protein (gm) | 88.6 (68.4−116.0) | 80.0 (61.6−102.3) | 84.9 (66.4−108.0) | 91.5 (70.4−116.8) | 91.1 (69.5−115.9) |

| Carbohydrate (gm) | 286.3 (210.4−368.9) | 252.1 (187.6−321.7) | 252.4 (195.2−326.7) | 258.1 (196.7−332.3) | 261.7 (198.3−335.4) |

| Total fat (gm) | 84.8 (59.6−116.5) | 76.3 (53.6−104.8) | 81.3 (59.9−108.6) | 87.8 (62.8−119.1) | 95.0 (70.3−124.7) |

| Total polyunsaturated fatty acids (gm) | 17.3 (11.6−25.2) | 15.4 (10.7−21.9) | 16.9 (11.8−23.6) | 17.5 (11.8−25.0) | 17.4 (12.8−24.3) |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 271.0 (167.0−410.9) | 271.5 (166.0−429.0) | 281.0 (177.5−413.0) | 304.0 (185.0−457.0) | 296.0 (186.5−469.7) |

| Calcium (mg) | 887.1 (581.0−1261.0) | 783.0 (544.0−1126.0) | 840.0 (574.0−1152.0) | 868.5 (617.5−1223.5) | 883.0 (630.0−1251.8) |

| Magnesium (mg) | 306.4 (222.5−389.5) | 275.0 (214.0−354.0) | 305.4 (227.5−392.5) | 320.1 (253.0−418.9) | 322.0 (260.0−418.0) |

| Alcohol (gm) | 0 (0−7.55) | 0 (0−13.0) | 0 (0−16.3) | 0 (0−24.0) | 0 (0−17.4) |

| Caffeine (mg) | 53.5 (2.86−129.0) | 98.5 (61.0−156.5) | 189.5 (137.0−245.0) | 332.0 (256.0−420.0) | 678.0 (528.5−860.9) |

| Vitamin A (mcg) | 607.6 (353.5−925.5) | 546.5 (333.0−850.0) | 590.5 (360.0−884.5) | 625.0 (389.0−965.0) | 535.0 (345.0−863.0) |

| Vitamin E (mcg) | 7.4 (5.0−10.8) | 6.6 (4.5−9.2) | 7.4 (5.0−10.3) | 7.7 (5.2−10.7) | 7.2 (5.2−10.4) |

| Coffee Consumption (Cup b/Day) | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| 0 | Ref | - | - | - |

| <1 | 1.18 | 0.77 | 1.80 | 0.439 |

| 1−<2 | 1.42 | 0.96 | 2.10 | 0.078 |

| 2−<4 | 1.53 | 0.90 | 2.61 | 0.114 |

| 4+ | 1.81 | 0.86 | 3.79 | 0.116 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Jian, Z.; Yuan, C.; Jin, X.; Li, H.; Wang, K. Coffee Consumption and Prostate Cancer Risk: Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010 and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2317. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072317

Wang M, Jian Z, Yuan C, Jin X, Li H, Wang K. Coffee Consumption and Prostate Cancer Risk: Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010 and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. Nutrients. 2021; 13(7):2317. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072317

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Menghua, Zhongyu Jian, Chi Yuan, Xi Jin, Hong Li, and Kunjie Wang. 2021. "Coffee Consumption and Prostate Cancer Risk: Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010 and Mendelian Randomization Analyses" Nutrients 13, no. 7: 2317. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072317

APA StyleWang, M., Jian, Z., Yuan, C., Jin, X., Li, H., & Wang, K. (2021). Coffee Consumption and Prostate Cancer Risk: Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010 and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. Nutrients, 13(7), 2317. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072317