1. Introduction

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are responsible for the largest share of total health-related burden in the European Union (EU): they account for approximately 9 out of every 10 deaths and disability adjusted life years (DALYs) [

1]. The four major NCDs, cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes mellitus, are responsible for at least 25% of the total healthcare spending, which is equivalent to an economic cost of 2% of the EU gross domestic product [

2]. Among the avoidable risk factors, energy-dense diets high in fat, sugars and salt and low in fibre are one of the key risk factors for NCDs, thus contributing to the high health and economic burden linked to them [

3,

4].

Many national programs and strategies, both voluntary and mandatory, are in place to regulate marketing of front-of-pack labelling of such products. In addition, efforts to improve the nutritional quality of the food offerings are underway at the EU level through voluntary policies (Frameworks for National Salt Initiatives (2008) [

5], National Initiatives on selected nutrients (2011) [

6], the Annexes on Saturated Fat (2012) [

7] and Added Sugars (2015) [

8] and the roadmap for Action on Food Product Improvement (2016) [

9]), and mandatory targets, standards and restrictions on nutrient content of industrially processed foods (i.e., Directive for the prohibition of added sugars in fruit juices (2012) [

10] and the Regulation on trans fats (2019) [

11]). More recently, the importance of healthy diets is also highlighted by the Farm to Fork Strategy [

12] and Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan [

13]. Beyond promoting a common European approach towards salt, sugars and fat intake reductions, these initiatives aim at encouraging a participatory engagement with public authorities and the food-processing sector, holding them accountable for food reformulation progress.

Independent of the type of action undertaken at national and regional levels, monitoring and surveillance are crucial to understand the progress towards achieving the reformulation initiatives’ targets [

14,

15]. The comparison between food and nutritional data across Europe is often hampered by the lack of standardisation and harmonisation between national food classifications, nomenclatures or sources of data [

16]. In this sense, one of the objectives of the Joint Action on Implementation of Validated Best Practices in Nutrition (Best-ReMaP) [

17] is to work towards developing a European Standardised Monitoring system for the reformulation of processed foods for countries without existing systems, based on already available tools and expertise. However, given that this initiative started at the end of 2020, results will take time to materialise.

In the absence of an existing and consolidated system to monitor Europe-wide reformulation efforts, this paper aims to assess progress on the existing commitments across European countries between 2015 and 2018. For that, we combine detailed market share and sales data with nutrition composition data from Euromonitor International to calculate market-share weighted averages of salt, total sugars, saturated fat and fibre content in selected food groups—most of them prioritised in several European frameworks. By integrating changes in nutritional composition of the food offer with changes in sales, this approach also provides insights into the ‘true’ average nutrient contents sold to consumers through different packaged food and soft drinks categories. Despite not measuring exactly what individuals have consumed, market data can be used by researchers and policymakers to keep track of the overall nutritional quality of the packaged food and drinks offered to and purchased by citizens [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

The limited availability of food supply and composition data poses several challenges on assessing reformulation initiatives, which may explain why empirical peer-reviewed studies in this area have been relatively sparse. Studies reporting de facto changes have mainly taken advantage of nationally representative cross-sectional surveys to analyse the nutritional quality of the food supply over time. Most of these studies have mainly focused on evaluating the trends of a specific nutrient in selected food groups [

19,

21,

23,

25,

26], or intended to compare the nutritional quality of similar food products across different countries at a specific point in time [

16,

18]. Compared to national dietary surveys and food composition tables, a third-party can offer more granular, frequent and standardised information on food sales and composition data disaggregated by type of product and brands, also avoiding reliance on individual recall [

24]. Therefore, through the use of detailed and up-to-date commercially supplied food sales and composition data for many European countries, we attempt to reduce the literature gap by assessing the nutritional quality of packaged food and soft drinks sold through the retail sector, looking at several nutrients and food groups. By directly comparing the recent trends among many European countries, our findings allow the identification of food groups and nutrients that have presented progress as well as those that require more attention from policymakers, industry and consumers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

Euromonitor International [

27] is a commercial global market research company providing data on the Packaged Food and Soft Drinks industries. Their Packaged Food and Soft Drinks databases include market-sized data of food/drink subcategories in value and volume terms, in addition to product/brand and company shares—which are available in volume and value terms for Soft Drinks, but only in value for the Packaged Food industry. In addition, the Nutrition database displays nutrient market sales volumes, and brand volumes on retails sales as well as back-of-pack labelling information on nutrient content (energy, carbohydrates, sugars, fibre, fat, saturated fat, protein and salt) per 100 g (or 100 mL) for the Soft Drinks and Packaged Food industries. Packaged Food/Soft Drinks and Nutrition data have been available since 2005 and 2014 respectively, until 2019, covering 5 subcategories of Soft Drinks and 16 subcategories of Packaged Food. Both datasets are frequently updated with five years of back-trended historic data and five years of forecasts.

Euromonitor employs a research methodology of sourcing nutrition data predominantly online through brand/retailer websites, with store checks carried out when the information cannot be found online. The Nutrition database only tracks products sold through retail outlets (excluding, for example, restaurants, cafés/bars and vending machines). Therefore, only retail sales are considered in this analysis. The company relies on: (i) the regular updates of the relevant retailer’s websites, and (ii) the accuracy of the data provided on the label—so it is assumed that manufacturers provide accurate and up-to-date information in line with EU regulations.

Within Europe, the company researches nutrition data for 19 of the EU27 countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Hungary, Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Finland and Sweden), the United Kingdom and 2 countries that are part of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), Norway and Switzerland. Market data is available for 28 European countries. As for all countries for which nutrition data is available market data also is, our study focuses on the 22 European countries listed above.

2.2. Data Collection and Processing

As there is no pre-existing integration of Packaged Food/Soft Drinks and Nutrition databases available in the company’s platform, we created a key variable with the lowest level of product disaggregation (product/brand), which enabled the matching between both databases. For this analysis, we focused on 14 categories and 152 subcategories (see

Table A1,

Appendix A) of packaged foods and soft drinks that commonly represent major sources of added sugars, salt, saturated fat and fibre across different European countries. Moreover, these were also targeted in several national priorities and plans as well as in regional initiatives, such as the 2011 EU Framework for National Initiatives on Selected Nutrients [

6].

After compiling and extracting market and nutrition data at the product/brand level, we removed those entries with: (i) missing market share, (ii) zero market share, (iii) missing/zero market value/volume and (iv) missing sugars, saturated fat, salt and fibre content data. For each remaining product/brand, we calculated the annual volume sold (in litres for Soft Drinks and tonnes for all other products) by multiplying the market share (in %) and the annual volume sold of the corresponding subcategory. Given that the market share data in volume terms is available only for Soft Drinks in Euromonitor, we used the value share to calculate total volume sold for all other categories, which may overestimate the volume sold of products that are more expensive per unit volume. We later estimated the market coverage for each category/subcategory based on the sum of total volumes of products in each category and the total volume of the category directly extracted from Euromonitor. In 2020, Euromonitor modified the 2019 Nutrition edition data structure from a product/brand level to a stock-keeping unit (or SKU) approach, which no longer allows the direct integration of market and nutrition data at the product/brand level. Thus, to ensure consistency, repeatability and reproducibility of our analysis, we used sales data from 2015 and 2018, which corresponds to data released by Euromonitor in 2016 and 2019.

Table 1 presents the final list of packaged food and beverages categories assessed in this paper, and the number of products/brands contained in each category and the respective market coverage by country in 2018. Overall, more than 23,000 products/brands were analysed across 14 packaged food and soft drinks categories, covering, on average, 72% of the market for these categories. It is also possible to notice that some categories such as Dairy, Soft Drinks, Sauces, Dressings and Condiments (S, D & C), Confectionary and Sweet Biscuits, present many product variants. Data for 2015 covers approximately 22,400 products/brands that jointly represent 68% of the market (

Table A2,

Appendix A), which suggests that the total number of products by category and their respective market coverage remained relatively constant over the 2015–2018 period.

Despite the high number of products/brands, some categories (such as Rice, Pasta and Noodles (R, P & N) and Baked Goods) present a relatively lower market coverage, while others contained few products that jointly represent a significant part of the total market in some countries (e.g., three products/brands represented 66% of the Greek market for soups), which justifies the focus of the analysis of the nutrient contents at the category level.

2.3. Estimation of the Market-Share Weighted Average for Selected Nutrients

To evaluate the broader nutrient profile of the food offer in Europe, we took into account the market dynamics of each product category/subcategory by adopting a market-share weighted average approach [

18,

19,

21]. For this, we calculated the total annual retail volume (in grams/millilitres) of product/brand

i (

Vi) and their respective category

V (

). If

Ni represents the salt, sugars, saturated fat or fibre content of each product/brand

i (in grams per 100 g/100 mL) and

Mi indicates their corresponding market share (in % volume for Soft Drinks and in % value for all other categories), we can calculate the weighted mean nutrient content (

) at the category level as follows:

Based on these estimates, we later calculated per capita nutrient sales values (g/pc/day) using mid-year population data for 2015 and 2018 from the European Health for all Database (HFA-DB) [

28] and scaled these estimates according to the respective market coverage (as presented in

Table 1) to represent 100% of the retail market. Therefore, while we are able to identify the contribution of specific products/brands to the overall quantity of nutrients sold within major packaged food and soft drinks categories in the EU, we followed [

20,

22] and assumed that the remainder of the market presents the same characteristics and evolution as our sample. This assumption minimizes data distortion given that many categories present a relatively high market coverage, and its magnitude remained stable across the analysed years [

22]. Additionally, this assumption is founded on the fact that small and local companies represented by the remainder of the market are less likely to have the capacity for reformulation [

20].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as weighted mean, arithmetic mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum. Linear regressions were used to generate two-tailed, homoscedastic Student’s t-tests to identify if there was a significant change in the weighted and arithmetic mean nutrient content of packaged food and soft drinks categories between 2015 and 2018. All data were analysed using the STATA/SE version 15.1, and R.

4. Discussion

This paper analysed the trends of the nutritional quality of packaged food and soft drinks with respect to nutrients of public health priority, i.e., sugars, salt, saturated fat and fibre. We paired commercially available food composition data with market share and sales data and assessed 14 packaged foods and drinks categories sold in 22 European countries between 2015 and 2018. We provided novel insights on (i) how much of these nutrients were sold through these product groups in 2018 vs. 2015, (ii) how much the content of these nutrients changed in the food and drink offers and (iii) by analysing market-weighted mean nutrient contents, how the combination of nutrient content, sales and consumer preferences have evolved against public health nutrition objectives towards reducing intakes of sugars, saturated fat, salt and increasing those of fibre.

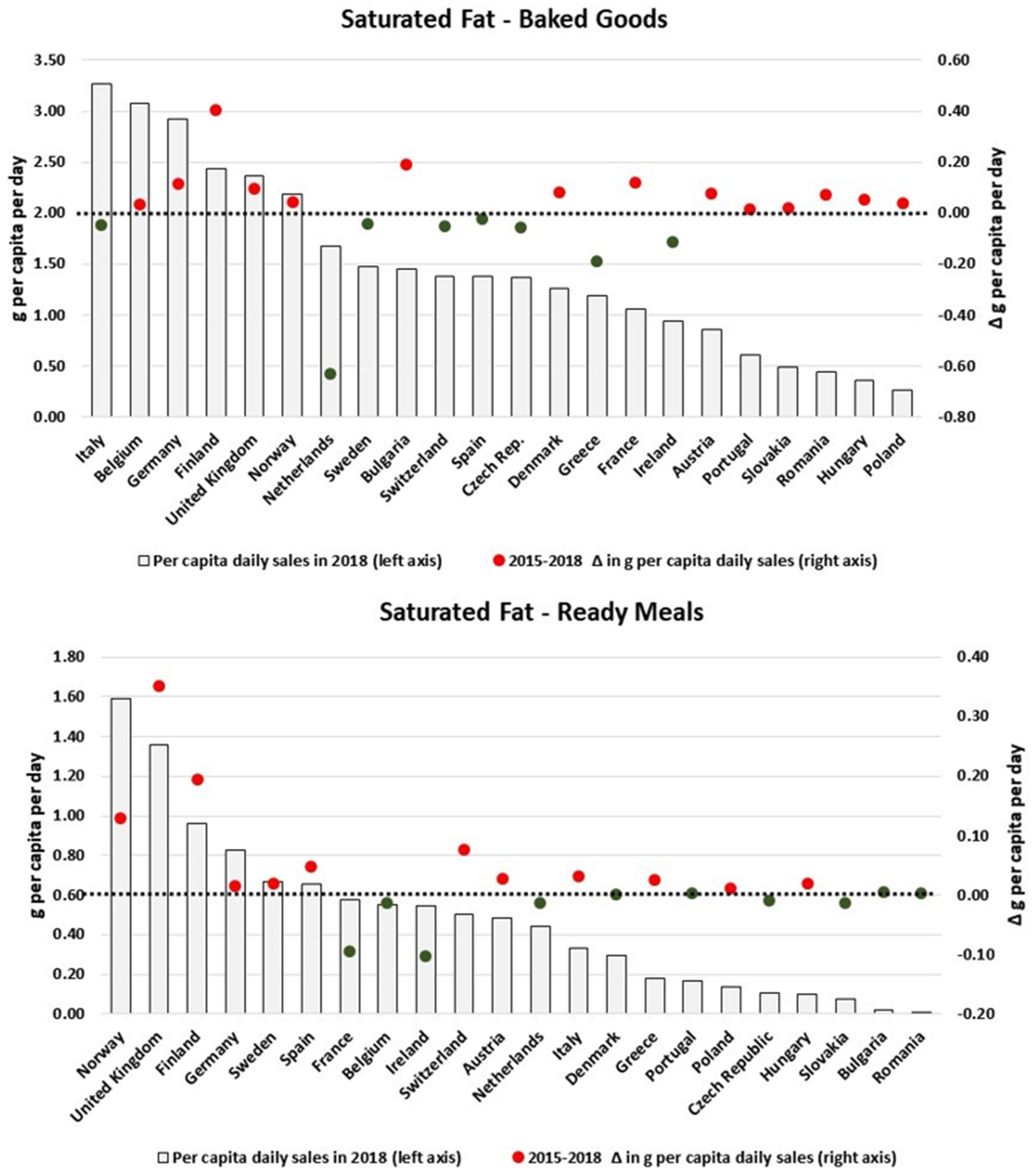

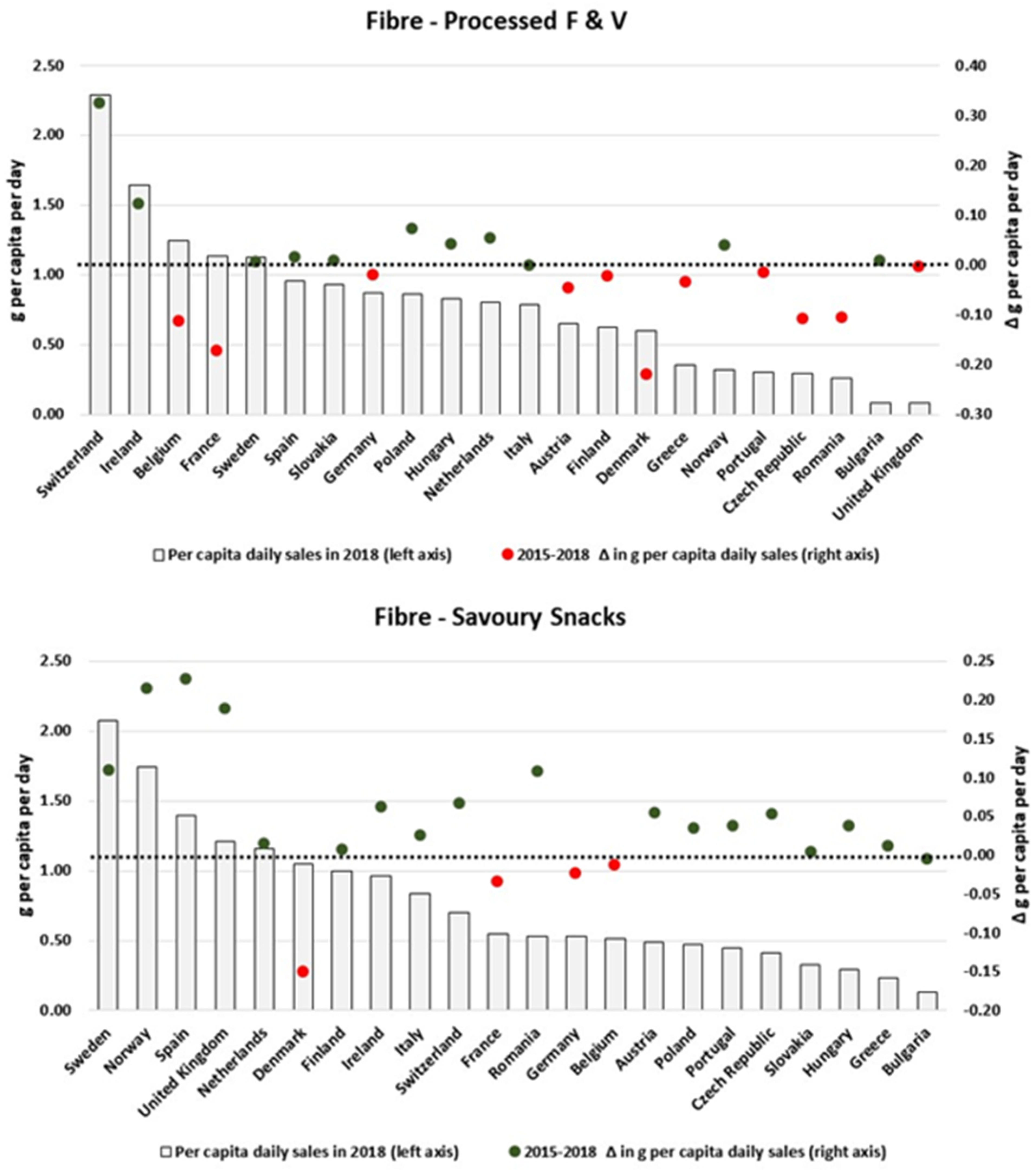

First, our daily per capita estimates for Europe indicate that the largest volumes of nutrient sales come from few product categories: Soft Drinks, Confectionary, Dairy and Baked Goods represent almost 80% of daily per capita sugars sales. For saturated fat, Dairy, Processed M & S, Baked Goods and Sweet Biscuits also accounted for a similar share of the estimated daily per capita sales. Salt sold through Processed M & S, Baked Goods and S, D & C accounted for 75% of the total per capita sales. At the same time, only two categories (Baked Goods and Processed F & V) were responsible for almost 60% of per capita sales of fibre. In addition, the results of the absolute changes in daily per capita sales in Europe suggest that few categories presented improvements in their nutritional content: sugars in Breakfast Cereals and Soft Drinks, saturated fat in Processed M & S, Sweet Biscuits and Baked Goods, salt in Processed M & S and Processed F & V and fibre in Savoury Snacks, Breakfast Cereals and Sweet Biscuits. Despite the progress observed in these categories, the magnitudes of the estimated changes lag behind when compared to the targets/benchmarks established by several initiatives, such as the 10% reduction for added sugars over a 5-year period [

8], and the decreases of 16% and 5% for salt [

5] and saturated fat [

7] respectively, in 4-year periods. While the European aggregate estimates are useful to track changes in nutrient sales over time, they also hide severe heterogeneities among countries. For example, approximately 75% of the analysed countries presented some decrease in per capita levels of sugars sales attributable to Soft Drinks. On the other hand, the overall reduction in per capita sales of salt attributable to Processed M & S could be mainly attributed to only 4 countries. Likewise, few countries were the main contributors to the recent changes observed in daily per capita volumes of total sugars and fibres sold as Breakfast Cereals. Yet, despite some improvements observed in a few categories and nutrients, the progress against public health objectives on the amounts of sugars, saturated fat, salt and fibre being sold to European citizens through packaged food and soft drinks is modest. The amounts sold remain close to the 2015 levels (70 g/pc/day for sugars, 8 g/pc/day for saturated fat, 3 g/pc/day for salt and 7 g/pc/day for fibre on a basis of approximately 600 kcal/pc/day), and when compared to reference intake values from the Food Information to Consumers (FIC) regulation (90 g/pc/day for sugars, 20 g/pc/day for saturated fat, 6 g/pc/day for salt) and adequate intake of 25 g/pc/day for fibre [

29], all on a reference basis of 2000 kcal/pc/day, it is possible to note that the levels of sugars and salt are of the most concern.

Second, beyond identifying great variability of the nutritional composition within and among packaged food and soft drinks categories, our estimates of the market-share weighted mean nutrient values suggest that the aggregated amount of sugars sold to European citizens was reduced only in 2 out of the 9 analysed categories (Breakfast Cereals and Soft Drinks), and even increased in the case of Sweet Biscuits. For saturated fat, reductions were observed in 2 out of the 9 assessed categories (Sweet Biscuits and Processed M & S), and for salt, reductions were observed only for products belonging to Processed M & S, and a significant increase was even estimated for Baked Goods. In general, the magnitudes of the improvements were rather small since the overall amounts of sugars, saturated fat and salt sold through these categories decreased by 3.3%, 4.4% and 2.1%, respectively. Moreover, statistically significant decreases in the market-share weighted fibre content were estimated for 1 out of the 9 assessed categories (Ready Meals) and overall, amounts of fibre sold across all product groups decreased by 2.1% between 2015 and 2018. In addition, our comparative analysis between the market-share weighted nutrient mean of paired and unpaired products point to large differences in sales and reformulation dynamics. For some categories and nutrients (such as saturated fat in Processed M & S, saturated fat and sugars in Sweet Biscuits), the changes might be explained by the net effect of the introduction/discontinuation of products with lower/high nutrient content between 2015 and 2018. For others (e.g., sugars in Breakfast Cereals and Soft Drinks and salt in Baked Goods), overall changes could be attributable to reductions/increases in market share of products with relatively high/low nutrient content, but also to some reformulation of those products which have been persistently sold in the European market.

Nevertheless, for the nutrients and categories in which a statistically significant change in the market-weighted nutrient content was identified, similar trends were also observed for their daily per capita nutrient sales. These findings consistently reflect different aspects of the overall quality of the food: the nutrient composition of the food supply and the average availability, market success of food and drinks with better or not so good nutrient profiles and the preferences of European citizens towards these products. In addition, the fact that most of the categories did not present a statistically significant change in their market-weighted nutrient content may indicate that just reformulating products or launching new ones with better nutrient profiles does not suffice to markedly impact sales and population diets if consumer preference for such products does not increase contemporaneously. Arguably, policies need to also address in parallel the food environment, supporting actions on educating, informing and incentivising consumers towards healthier choices.

Third, our results also suggest modest progress in the nutritional content of the food supply across the European countries. For some categories, such as Dairy, Sweet Biscuits and Confectionary, decreases of more than 5% in the respective market-share weighted total sugars content (in g/100 g) were observed only for 5 out of the 22 countries analysed; for others (e.g., S, D & C), there were only 2 countries achieving this level of reduction. Considering the EU Added Sugar Annex [

8] and its 10% added sugar reduction target by 2020 against the 2015 baseline level, our findings suggest that countries risk falling short on their commitments to reduce the content of sugars in packaged foods and soft drinks. Similarly, the number of countries that had their market-share weighted mean of saturated fat reduced by more than 5% varies from 4 (e.g., for Dairy and Breakfast Cereals) to 9 countries (e.g., for Processed M & S). Decreases of more than 5% in the market-share weighted mean of salt were more frequent for Ready Meals and Processed F & V (9 countries) and Processed M & S and Savoury Snacks (7 countries). In the case of fibre, increases of more than 5% in the market-share weighted mean for Sweet Spreads and Soup were found for 7 countries, while for Sweet Biscuits and Ready Meals, this threshold was achieved in 6 and 5 countries, respectively. Results are even more worrying for other categories (such as Breakfast Cereals, Processed F & V and Savoury Snacks), as they point to decreases in the market-share weighted mean of fibre for more than 70% of the analysed countries.

Direct comparisons between our study and previous ones are limited by different methodologies, timeframe and product categorisation. However, our country-level results are consistent with the recent trends and degree of nutrient variability reported by previous peer-reviewed studies using similar methodological approaches and timeframe. For sugars, the authors of [

19] used an annual cross-sectional study using nutrient composition data for products available online to assess changes in sales of soft drinks in the UK from 2015 to 2018. They estimated a 30% decline in the per capita volume of sugars sold from soft drinks in the UK between 2015 and 2018 (equivalent to a reduction of 4.6 g per capita per day), which were translated into a statistically significant reduction of 1.5 g/100 mL of the sales-weighted mean sugars content of soft drinks. Using the same methodology, the same authors estimated a 13.3% decrease (95% confidence intervals (CI): −19.2% and −7.4%) in the sales-weighted mean sugar content for breakfast cereals in the same period [

20], close to our point-estimate of −9.0%. Similar analyses were conducted by [

25], and they found that energy drinks presented a statistically significant reduction of 10% in their total sugars content (from 10.6 (±3.2 g) to 9.5 (±3.3 g) g/100 mL) between 2015 and 2017 in the UK. Manufacturers of the sugar-reduced products had either only reduced sugars or had alternatively reduced sugars, replaced with non-caloric sweeteners without changing the product name, for example, by calling the product ‘light’ and so on. Despite the observed reduction, the sugars content of energy drinks was still at concerning levels by the end of the study period. Particularly for Soft Drinks in the UK, our estimates point to a 5% reduction (−0.3 g/100 mL) in the market-share weighted sugars mean and a 5% decrease (−0.3 g/pc/day) in the daily per capita sales between 2015 and 2018.

Focusing on yogurts, the authors of [

26] detected a highly significant reduction of 14% in the median total sugars contents in 2019 compared to those in 2016 (from 11.9 (CI: 8.8, 13.6) to 10.4 (CI: 6.6, 13.0) g/100 g) based on online data—nutrient information, serving size, size of pack, claims on pack and ingredients—collected from major UK supermarkets. When scrutinising paired products, i.e., products that were present with the same brand name both in 2016 and 2019, only 1/3 of the 539 products surveyed had reduced sugars contents, with a smaller mean difference of −0.65 g/100 g (CI: −0.78, −0.52). This suggests that the overall median had dropped due to the discontinuity of products with relatively higher sugars content and/or the introduction of new products with relatively lower sugars content. These reported trends are aligned with the results presented in this study and others [

20]. Taking Dairy as a reference category, we calculated decreases of −0.7 g/100 g (or −6%) in the market-share weighted sugars mean for the UK between 2015 and 2018.

For salt, using Dutch food composition data with monitoring reports and relevant labelling information collected from the largest supermarket chain, the authors of [

30] found no statistically significant change in sodium levels of processed meat products between 2011 and 2015 in the Netherlands. However, according to the authors, a reversal in this trend was expected to occur in the upcoming years as per the 2014 agreement between the Dutch government and the private sector, in which a 10% mandatory reduction target for meat products to be reached before the end of 2020 was established. The authors of [

30] also estimated a significant reduction in the saturated fat levels for only one subcategory of meat products (heated meat products): from approximately 10 g/100 g (±3.0 g) in 2014 to 8 g/100 g (±3.0 g) in 2015. Notably, a 5% target for saturated fat was also established by the Government and the private sector for these products. For the 2015–2018 period, we calculated decreases of 16% (or −0.3 g/100 g) and 19% (or −1.1 g/100 g) in the market-share weighted salt and saturated fat mean for Processed M & S in the Netherlands, which suggests that the establishment of mandatory targets might have been effective in reducing salt and saturated fat levels in meat products in the country.

The grey literature also supports and complements our findings and the ones from peer-reviewed studies. A monitoring report from Public Health England (PHE) highlighted that there has been progress in some, but not all, food categories between 2015 and 2019. Sustained progress in sales-weighted average sugars was observed for breakfast cereals (−13.3% or −2.2 g/100 g) and yogurt and fromage frais (−12.9% or −1.6 g/100 g); remarkably, sales-weighted average sugars in soft drinks subject to the levy decreased by 44% (or −1.7 g/100 mL), even though overall sales volume increased by 14%. In contrast, sugars levels in chocolate and sweet confectionery remained relatively unchanged, with variations of −0.4% (−0.2 g/100 g) and −0.1% (−0.04 g/100 g). Overall, the average sugars reduction across all monitored food categories (including the ones previously mentioned) stands at 3% from 2015 to 2019, falling extremely short of the targeted 20% reduction by 2020 [

31]. PHE also reported a slow progress in the salt reduction programme, in which just over half (52%) of the salt reduction targets for product averages set in 2014 were met by 2017. Retailers’ own brands made more progress than manufacturers towards achieving these targets, meeting 73% of them compared with manufacturers, who met 37%. However, where targets on maximum salt contents were set, 83% of in-home products met these targets vis-à-vis 71% for out-of-home products [

32]. Another study for the Netherlands, released by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, found that the salt content in bread in 2016 was, on average, 19% lower than in 2011. Certain savoury sauces, soups, tinned vegetables and pulses, and chips, had between 12% and 25% less salt for the same period. However, despite the improvements in salt content, the average saturated fat and sugars content in most food categories remained at the same levels over the past years [

33].

The results of this study are relevant and serve to document and provide evidence to policymakers, industry and citizens on the evolution of sugars, saturated fat, salt and fibre content of packaged foods and soft drinks sold in Europe. The strength of the market-share weighted average approach lies in its ability to capture the true market influence of products that could otherwise be interpreted as outliers, such as those with a low nutrient content but high market share or, alternatively, those with a low market share but high nutrient content. It also gives greater impetus to the reformulation of leading market products and limits the impact of new and/or reformulated products with improved nutrient contents but low market share. It should also be noted that this approach does not only capture producers’ changes in the food offer, it also reflects the market success of products with better nutritional quality with consumers, which also depends on consumer attitude, preference and motivation (e.g., shift towards existing low-sugar or sugar-free products).

However, despite being an interesting and effective data source to monitor the progress of the food quality across different countries, there are limitations on the use of commercial data and on the results generated by them [

24]. Given that Euromonitor’s methodological approach heavily relies on sampling only the most representative variants of a product/brand within each country, our results should be interpreted as reflections of the behaviour and efforts of the market-leading brands and products rather than the performance of the overall food supply. Furthermore, Euromonitor has innovated its data collection methodology using automatic scraping of product information from online stores, affecting the data in the nutrition module from 2019 onwards. Whilst this comes with advantages, such as nutrition information at the stock keeping unit (or SKU) level rather than most representative variant of brands, this break in methodology does not easily allow for assessing trends in daily per capita nutrient sales figures and alike from before 2019 and 2019 onwards. We are also constrained by the accuracy of the information presented on the label, as it is assumed that manufacturers provide accurate and up-to-date information, in line with EU regulations. Additionally, in the absence of market share in value terms in the Euromonitor database, the assumption made in this paper to use value shares as the equivalent to volume share can overestimate the market share of products that are more expensive per unit volume, as well as the point-estimates of the weighted average nutrient content. Lastly, as data on package size is not available in Euromonitor’s Nutrition database, it was not possible to separate the effects of reformulation and changes in package size on the market-share weighted nutrient mean estimates.

In this sense, the development of a standardised system to track wide reformulation initiatives across the EU Member States appears to be very much needed [

14], and the outcomes of the joint endeavour of EU countries within the Joint Action Best ReMaP [

17], which builds on previous pan-European efforts, is expected to reduce this gap. This system could ensure sustainability on the monitoring and surveillance of nutrition policies at the country and the European level, as well as to help in identifying best practices at a bigger scale, and to establish unbiased targets for reduction of sugars, salt and saturated fat, as well as increments in fibre among countries. Improvements in the overall quality of the food offer would also contribute to enhancing diets (a priority in several EU Strategies, such as the Farm to Fork Strategy or Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan), which could be then translated into significant benefits for the population by promoting health and reducing the health and economic burden of NCDs.

Future research is needed to better understand the supply and demand drivers behind changes in nutrition content, as well as the impact of integrated strategies on sales, purchases and ultimately diets and health. By combining food composition and purchasing data, the methodology developed in [

34] and applied to the French context in [

22] allows the decomposition of the overall change in the nutrient content into what can be attributable to: (i) consumers switching from some products to others, (ii) firms reformulating food products and (iii) net product introduction (the combination of new products and product withdrawals). Additional studies could also shed light on the evolution of portion sizes across different food categories and countries, as well as its impact on the overall market-share weighted mean of selected nutrients.