Poor Dietary Quality and Patterns Are Associated with Higher Perceived Stress among Women of Reproductive Age in the UK

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Measurements and Procedures

2.1.1. Diet

2.1.2. Dietary Data Analysis

2.1.3. Mental Health Indicators

2.1.4. Physical and Socio-Demographic Characteristics

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

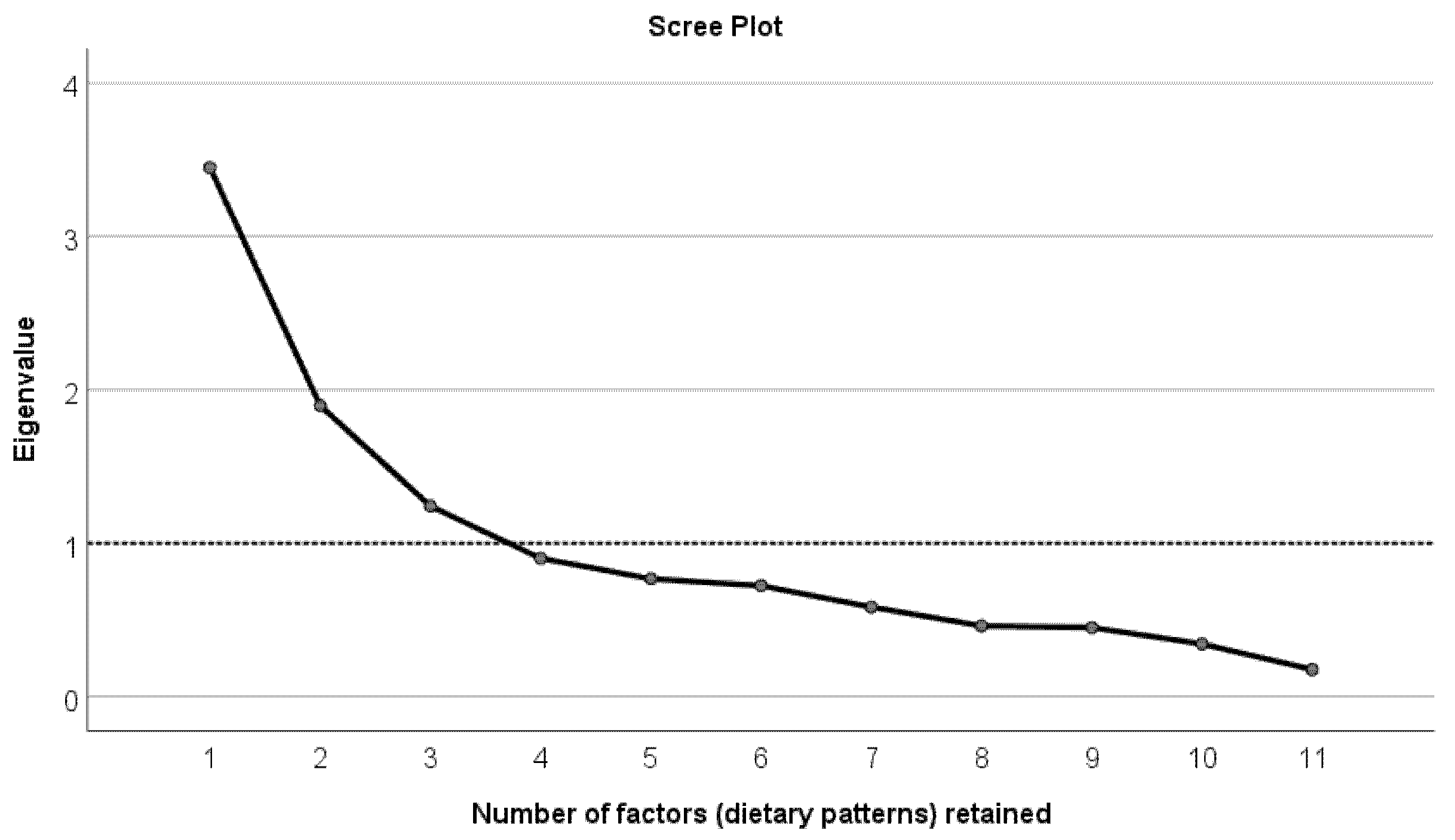

Factor Analysis

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Durst, J.K.; Tuuli, M.G.; Stout, M.J.; Macones, G.A.; Cahill, A.G. Degree of obesity at delivery and risk of preeclampsia with severe features. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 651.e1–651.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelinckx, I.; Devlieger, R.; Beckers, K.; Vansant, G. Maternal obesity: Pregnancy complications, gestational weight gain and nutrition. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.-M.; Yang, H.; Zhu, W.-W.; Liu, X.-Y.; Meng, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Shang, L.-X.; Cai, Z.-Y.; Ji, L.-P.; Wang, Y.-F.; et al. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes stratified for pre-pregnancy body mass index. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2015, 29, 2205–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Effects of pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on maternal and infant complications. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisonkova, S.; Muraca, G.; Potts, J.; Liauw, J.; Chan, W.-S.; Skoll, A.; Lim, K.I. Association Between Prepregnancy Body Mass Index and Severe Maternal Morbidity. JAMA 2017, 318, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Weight Management in Pregnancy (i-WIP) Collaborative Group. Effect Of Diet And Physical Activity Based Interventions In Pregnancy On Gestational Weight Gain And Pregnancy Outcomes: Meta-Analysis Of Individual Participant Data From Randomised Trials. BMJ 2017, 358, j3991. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, D.M.; Jeffery, R.W. Relationships Between Perceived Stress and Health Behaviors in a Sample of Working Adults. Health Psychol. 2003, 22, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.; Fang, C. Stress is Associated with Unfavorable Patterns of Dietary Intake Among Female Chinese Immigrants. Annal. Behav. Med. 2011, 41, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N.; Bilgel, N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, K.W.; Hearst, M.O.; Escoto, K.; Berge, J.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Parental employment and work-family stress: Associations with family food environments. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugero, K.D.; Falcon, L.M.; Tucker, K. Relationship between perceived stress and dietary and activity patterns in older adults participating in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Appetite 2011, 56, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, E.J.; Alvarez, D.; Martinez-Velarde, D.; Vidal-Damas, L.; Yuncar-Rojas, K.A.; Julca-Malca, A.; Bernabe-Ortiz, A. Perceived stress and high fat intake: A study in a sample of undergraduate students. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichianson, J.R.; Bughi, S.A.; Unger, J.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Nguyen-Rodriguez, S.T. Perceived stress, coping and night-eating in college students. Stress Health 2009, 25, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastaskin, R.S.; Fiocco, A.J. A survey of diet self-efficacy and food intake in students with high and low perceived stress. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohafza, H.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Sadeghi, M.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M.; Sajjadi, F.; Khosravi-Boroujeni, H. The Association Be-tween Stress Levels And Food Consumption Among Iranian Population. Arch. Iran. Med. 2013, 16, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- El Ansari, W.; Adetunji, H.; Oskrochi, R. Food and Mental Health: Relationship between Food and Perceived Stress and Depressive Symptoms among University Students in the United Kingdom. Central Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 22, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papier, K.; Ahmed, F.; Lee, P.; Wiseman, J. Stress and dietary behaviour among first-year university students in Australia: Sex differences. Nutrients 2015, 31, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.B.; O’Connor, R.C. Perceived changes in food intake in response to stress: The role of conscientiousness. Stress Health 2004, 20, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryon, M.; Carter, C.; DeCant, R.; Laugero, K. Chronic Stress Exposure May Affect the Brain’s Response to High Calorie Food Cues And Predispose To Obesogenic Eating Habits. Physiol. Behav. 2013, 120, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Chung, H.; Kim, W. Psychological Distress Is Associated with Inadequate Dietary Intake In Viet-namese Marriage Immigrant Women In Korea. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowles, E.R.; Bryant, M.; Kim, S.; Walker, L.O.; Ruiz, R.J.; Timmerman, G.M.; Brown, A. Predictors of Dietary Quality in Low-Income Pregnant Women. Nurs. Res. 2011, 60, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowles, E.R.; Stang, J.; Bryant, M.; Kim, S. Stress, Depression, Social Support, and Eating Habits Reduce Diet Quality in the First Trimester in Low-Income Women: A Pilot Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widaman, A.; Witbracht, M.G.; Forester, S.M.; Laugero, K.D.; Keim, N.L. Chronic Stress is Associated with Indicators of Diet Quality in Habitual Breakfast Skippers. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.S.; Arsenault, J.E.; Cates, S.C.; Muth, M.K. Perceived stress, unhealthy eating behaviors, and severe obesity in low-income women. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isasi, C.; Parrinello, C.; Jung, M.; Carnethon, M.; Birnbaum-Weitzman, O.; Espinoza, R.; Penedo, F.; Perreira, K.; Schneiderman, N.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; et al. Psychosocial Stress Is Associated with Obesity and Diet Quality in Hispanic/Latino Adults. Annal. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczyk, R.T.; El Ansari, W.; Maxwell, A.E. Food consumption frequency and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among students in three European countries. Nutr. J. 2009, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.M.; Cruz, S.Y.; Ríos, J.L.; Pagán, I.; Fabián, C.; Betancourt, J.; Rivera-Soto, W.T.; González, M.J.; Palacios, C. Alcohol consumption and smoking and their associations with socio-demographic characteristics, dietary patterns, and perceived academic stress in Puerto Rican college students. Puerto Rico Health Sci. J. 2013, 32, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson, J.E.; Sherwood, N.E.; Perry, C.L.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Depressive symptoms and adolescent eating and health behaviors: A multifaceted view in a population-based sample. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xie, B.; Chou, C.-P.; Koprowski, C.; Zhou, D.; Palmer, P.; Sun, P.; Guo, Q.; Duan, L.; Sun, X.; et al. Perceived stress, depression and food consumption frequency in the college students of China seven cities. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaled, K.; Tsofliou, F.; Hundley, V.; Helmreich, R.; Almilaji, O. Perceived stress and diet quality in women of reproductive age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morema, E.N.; Atieli, H.E.; Onyango, R.O.; Omondi, J.H.; Ouma, C. Determinants of Cervical screening services uptake among 18–49 year old women seeking services at the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital, Kisumu, Kenya. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proportion of Women of Reproductive Age (Aged 15–49 Years) Who Have Their Need for Family Planning Satisfied with Modern Methods (SDG 3.7.1). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/indicator-explorer-new/mca/proportion-of-women-of-reproductive-age-(aged-15–49-years)-who-have-their-need-for-family-planning-satisfied-with-modern-methods (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Hulley, S.; Cummings, S.; Browner, W.; Grady, D.; Newman, T. Designing Clinical Research, 4th ed.; Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Verkasalo, P.K.; Appleby, P.N.; Allen, N.E.; Davey, G.; Adlercreutz, H.; Key, T.J. Soya intake and plasma concentrations of daidzein and genistein: Validity of dietary assessment among eighty British women (Oxford arm of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition). Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 86, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, A.A.; Luben, R.; Khaw, K.T.; Bingham, S.A. The CAFE computer program for nutritional analysis of the EPIC-Norfolk food frequency questionnaire and identification of extreme nutrient values. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2005, 18, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, A.A.; Luben, R.; Bhaniani, A.; Parry-Smith, D.J.; O’Connor, L.; Khawaja, A.; Forouhi, N.; Khaw, K.-T. A new tool for converting food frequency questionnaire data into nutrient and food group values: FETA research methods and availability. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Survival in a Greek Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.; McCullough, M.; Newby, P.; Manson, J.; Meigs, J.; Rifai, N.; Willett, W.; Hu, F. Diet-Quality Scores and Plasma Concentrations Of Markers Of Inflammation And Endothelial Dysfunction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, H.; Chen, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, T. A review of statistical methods for dietary pattern analysis. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavolacci, M.P.; Ladner, J.; Grigioni, S.; Richard, L.; Villet, H.; Dechelotte, P. Prevalence and association of perceived stress, substance use and behavioral addictions: A cross-sectional study among university students in France, 2009–2011. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Steer, R.; Brown, G. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II, 2nd ed.; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- García-Batista, Z.E.; Guerra-Peña, K.; Cano-Vindel, A.; Herrera-Martínez, S.X.; Medrano, L.A. Validity and reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) in general and hospital population of Dominican Republic. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-P.; Gorenstein, C. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2013, 35, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes-Oliveira, M.H.; Gorenstein, C.; Neto, F.L.; Andrade, L.H.; Wang, Y.P. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a community sample. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2012, 34, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, D.L.; Coolidge, F.L.; Cahill, B.S.; O’Riley, A.A. Psychometric Properties of the Beck Depression Inventory—II (BDI-II) Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Behav. Modif. 2008, 32, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothe, K.B.; Dutton, G.R.; Jones, G.; Bodenlos, J.; Ancona, M.; Brantley, P.J. Validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a Low-Income African American Sample of Medical Outpatients. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 17, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subica, A.M.; Fowler, J.C.; Elhai, J.D.; Frueh, B.C.; Sharp, C.; Kelly, E.L.; Allen, J.G. Factor structure and diagnostic validity of the Beck Depression Inventory–II with adult clinical inpatients: Comparison to a gold-standard diagnostic interview. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic: Report of a WHO Consultation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, C.K.; Hankey, C.R.; Lean, M.E.J. Accuracy of on-line self-reported weights and heights by young adults. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell, R.; Kettel Khan, L.; Hughes, M.; Grummer-Strawn, L. Obesity in Women From Developing Countries. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Conde, W.L.; Lu, B.; Popkin, B. Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. Int. J. Obes. 2004, 28, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matore, E.; Khairani, A.; Adnan, R. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) For Adversity Quotient (AQ) Instrument among Youth. J. Crit. Rev. 2019, 6, 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.; Widaman, K.; Zhang, S.; Hong, S. Sample Size in Factor Analysis. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J.; Dodou, D.; Wieringa, P.A. Exploratory Factor Analysis with Small Sample Sizes. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2009, 44, 147–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boghossian, N.S.; Yeung, E.H.; Mumford, S.L.; Zhang, C.; Gaskins, A.J.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Schisterman, E.; for the BioCycle Study Group. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and body fat distribution in reproductive aged women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, A.; Wood, L.; Sebire, S.J.; Jago, R. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet among employees in South West England: Formative research to inform a web-based, work-place nutrition intervention. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaled, K.; Hundley, V.; Almilaji, O.; Koeppen, M.; Tsofliou, F. A Priori and a Posteriori Dietary Patterns in Women of Childbearing Age in the UK. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-D.; Dong, X.-W.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Tian, H.-Y.; He, J.; Chen, Y.-M. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with a higher BMD in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestle, M. Obesity. Halting the obesity epidemic: A public health policy approach. Public Health Rep. 2000, 115, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groesz, L.M.; McCoy, S.; Carl, J.; Saslow, L.; Stewart, J.; Adler, N.; Laraia, B.; Epel, E. What is eating you? Stress and the drive to eat. Appetite 2012, 58, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habhab, S.; Sheldon, J.; Loeb, R. The Relationship Between Stress, Dietary Restraint, And Food Preferences in Women. Appetite 2009, 52, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferranti, E.P.; Dunbar, S.B.; Higgins, M.; Dai, J.; Ziegler, T.R.; Frediani, J.; Reilly, C.; Brigham, K.L. Psychosocial factors associated with diet quality in a working adult population. Res. Nurs. Health 2013, 36, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ansari, W.; Berg-Beckhoff, G. Nutritional Correlates of Perceived Stress among University Students in Egypt. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14164–14176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, G.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Azadbakht, L.; Afshar, H.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Adibi, P. Adherence To The DASH Diet In Re-lation To Psychological Profile Of Iranian Adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 56, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Presnell, K.; Spangler, D. Risk Factors For Binge Eating Onset In aAdolescent Girls: A 2-Year Prospective Investiga-tion. Health Psychol. 2002, 21, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, T.; Epel, E. Stress, Eating And The Reward System. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 91, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrave, C.F.; Allen, C.E.; Allen, G.J. Spirituality and Health for Women of Color. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, I.; Gilad, S.; Limor, R.; Stern, N.; Greenman, Y. Ghrelin Stimulation by Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis Acti-vation Depends On Increasing Cortisol Levels. Endo. Connect. 2017, 6, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herhaus, B.; Ullmann, E.; Chrousos, G.; Petrowski, K. High/low cortisol reactivity and food intake in people with obesity and healthy weight. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewagalamulage, S.; Lee, T.; Clarke, I.; Henry, B. Stress, Cortisol, And Obesity: A Role For Cortisol Responsiveness in Iden-tifying Individuals Prone To Obesity. Domes. Anim. Endocrinol. 2016, 56, S112–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, E.; Webb, E.; Cummins, S. Change in commute mode and body-mass index: Prospective, longitudinal evidence from UK Biobank. Lancet Public Health 2016, 1, e46–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prady, S.L.; Pickett, K.E.; Croudace, T.; Fairley, L.; Bloor, K.; Gilbody, S.; Kiernan, K.E.; Wright, J. Psychological Distress during Pregnancy in a Multi-Ethnic Community: Findings from the Born in Bradford Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.A. A comparison of the socioeconomic characteristics, dietary practices, and health status of women food shoppers with different food price attitudes. Nutr. Res. 2006, 26, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.A.; Ng, B.K.; Sommer, M.J.; Heymsfield, S.B. Body composition by DXA. Bone 2017, 104, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellhammer, D.; Wüst, S.; Kudielka, B. Salivary Cortisol as A Biomarker in Stress Re-search. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picó, C.; Serra, F.; Rodríguez, A.; Keijer, J.; Palou, A. Biomarkers of Nutrition and Health: New Tools For New Approaches. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participants’ Characteristics(N (%)) | Total Sample | Alternate Mediterranean Diet Adherence Categories | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low aMDS (0–3) | Medium aMDS (4–6) | High aMDS (7–9) | |||

| 95 (39) | 113 (46) | 36 (15) | |||

| Physical and lifestyle characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) # | 24.0 (21.0–32.0) | 23.0 (21.0–29.0) | 25.0 (21.5–32.0) | 24.0 (20.3–35.0) | 0.277 |

| Age (years) * | 0.09 | ||||

| 18–24 | 124 (51) | 54 (57) | 51 (45) | 19 (53) | |

| 25–34 | 77 (32) | 26 27) | 44 (39) | 7 (19) | |

| 35–49 | 43 (17) | 15 (16) | 18 (16) | 10 (28) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) # | 23.7 (20.9–27.9) | 26.1 (21.5–49.4) | 23.7 (20.6–27.5) | 21.9 (20.3–23.9) | 0.093 |

| BMI * | 0.005 | ||||

| Underweight | 14 (6) | 4 (4) | 7 (6) | 3 (8) | |

| Normal Weight | 120 (49) | 38 (40) | 56 (50) | 26 (72) | |

| Overweight/obese | 108 (44) | 52 (56) | 50 (44) | 6 (17) | |

| Physical Activity (METs-h/wk) # | 1429 (464.3–2824.5) | 1159 (330.0–2615.0) | 1440 (479.3–2886.3) | 2380 (1325.5–3464.3) | 0.336 |

| Physical Activity level * | 0.018 | ||||

| Low (<600 MET minutes/week) | 76 (31) | 39 (41) | 33 (29) | 4 (11) | |

| Moderate (>600 MET minutes/week) | 114 (47) | 39 (41) | 55 (49) | 20 (56) | |

| High (>3000 MET minutes/week) | 54 (22) | 17 (18) | 25 (22) | 12 (33) | |

| Mental Health Indicator | |||||

| Stress # | 29 (22.0–33.0) | 31 (26.0–34.0) | 27 (22.0–27.0) | 26.5 (18.0–31.8) | 0.002 |

| Stress * | 0.001 | ||||

| Low-Medium | 103 (42) | 26 (27) | 58 (51) | 19 (53) | |

| Medium-High | 141 (58) | 69 (73) | 55 (49) | 17 (47) | |

| Depression # | 5 (2.0–12.0) | 5 (2.0–13.0) | 5 (2.0–11.0) | 5 (1.0–13.0) | 0.926 |

| Depression * | 0.07 | ||||

| Minimal (0–13) | 191 (78) | 73 (77) | 90 (80) | 28 (78) | |

| Mild (14–19) | 28 (11) | 15 (16) | 10 (9) | 3 (8) | |

| Moderate (20–28) | 12 (5) | 4 (4) | 8 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Severe (29–63) | 13 (5) | 3 (3) | 5 (4) | 5 (14) | |

| Participants’ Characteristics (N (%)) | Total Sample N (%) | Alternate Mediterranean Diet Adherence Categories | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low aMDS (0–3) | Medium aMDS (4–6) | High aMDS (7–9) | |||

| 95 (39) | 113 (46) | 36 (15) | |||

| Father’s education | 0.626 | ||||

| No qualifications | 23 (9) | 8 (8) | 11 (10) | 4 (11) | |

| Certificate of Secondary education (CSE) taken at 14–16 years at a lower level than GCSE | 57 (23) | 28 (29) | 25 (22) | 4 (11) | |

| O-level or GCSE examinations taken at 16 years | 71 (29) | 23 (24) | 35 (31) | 13 (36) | |

| A-level school examinations taken at 18 years | 45 (18) | 18 (19) | 19 (17) | 8 (22) | |

| Higher education | 48 (20) | 18 (19) | 23 (20) | 7 (19) | |

| Mother’s education | 0.399 | ||||

| No qualifications | 16 (7) | 5 (5) | 9 (8) | 2 (6) | |

| Certificate of Secondary education (CSE) taken at 14–16 years at a lower level than GCSE | 47 (19) | 24 (25) | 20 (18) | 3 (8) | |

| O-level or GCSE examinations taken at 16 years | 82 (34) | 26 (27) | 41 (36) | 15 (42) | |

| A-level school examinations taken at 18 years | 44 (18) | 17 (18) | 18 (16) | 9 (25) | |

| Higher education | 55 (23) | 23 (24) | 25 (22) | 7 (19) | |

| Father’s occupation | 0.424 | ||||

| Working as an employee | 92 (38) | 35 (37) | 42 (37) | 15 (42) | |

| On a government sponsored training scheme | 5 (2) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Self-employed or freelance | 68 (28) | 28 (29) | 30 (27) | 10 (28) | |

| Working paid or unpaid for your own or your family’s business | 31 (13) | 13 (14) | 15 (13) | 3 (8) | |

| Doing any other kind of paid work | 9 (4) | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 2 (6) | |

| Retired (whether receiving a pension or not) | 36 (15) | 8 (8) | 22 (19) | 6 (17) | |

| Long-term sick or disabled | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Mother’s occupation | 0.266 | ||||

| Working as an employee? | 101 (41) | 38 (40) | 43 (38) | 20 (56) | |

| On a government sponsored training scheme | 9 (4) | 4 (4) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Self-employed or freelance | 25 (10) | 6 (6) | 14 (12) | 5 (14) | |

| Working paid or unpaid for your own or your family’s business | 17 (7) | 9 (9) | 7 (6) | 1 (3) | |

| 20 (8) | 11 (12) | 6 (5) | 3 (8) | ||

| Doing any other kind of paid work | |||||

| Retired (whether receiving a pension or not) | 34 (14) | 8 (8) | 22 (19) | 4 (11) | |

| Looking after home or family | 27 (11) | 14 (15) | 11 (10) | 2 (6) | |

| Long-term sick or disabled | 11 (5) | 5 (5) | 5 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| Income per year | 0.047 | ||||

| <£13,000 | 119 (49) | 43 (45) | 54 (48) | 22 (61) | |

| £13,000 to £33,800 | 99 (40) | 45 (48) | 47 (41) | 7 (19) | |

| >£33,800 | 26 (11) | 7 (7) | 12 (11) | 7 (19) | |

| Parents’ annual income | 0.432 | ||||

| <£13,000 | 36 (15) | 14 (15) | 15 (13) | 7 (19) | |

| £13,000 to £23,400 | 51 (21) | 21 (22) | 25 (22) | 5 (14) | |

| >£23,400 to £33,800 | 69 (28) | 31 (33) | 33 (29) | 5 (14) | |

| >£33,800 to £52,000 | 47 (19) | 16 (17) | 20 (18) | 11 (31) | |

| >£52,000 | 41 (17) | 13 (14) | 20 (18) | 8 (22) | |

| Marital Status | 0.46 | ||||

| Single | 176 (72) | 67 (71) | 84 (74) | 25 (69) | |

| Married | 43 (18) | 16 (17) | 18 (16) | 9 (25) | |

| Divorced | 17 (7) | 9 (9) | 8 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Separated but still legally married | 6 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | |

| Widowed | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | |

| Smoking | 0.47 | ||||

| Current Smoker | 56 (23) | 25 (26) | 23 (20) | 8 (22) | |

| Ex-smoker | 27 (11) | 10 (11) | 11 (10) | 6 (17) | |

| Never smoked | 161 (66) | 60 (63) | 79 (70) | 22 (61) | |

| Religion | 0.437 | ||||

| No religion | 104 (43) | 36 (38) | 53 (47) | 15 (42) | |

| Christian | 105 (43) | 45 (47) | 42 (37) | 18 (50) | |

| Buddhist | 7 (3) | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Hindu | 9 (4) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| Jewish | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | |

| Muslim | 19 (8) | 7 (7) | 10 (9) | 2 (6) | |

| Sikh | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.231 | ||||

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 10 (4) | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| White | 177 (73) | 61 (64) | 82 (73) | 34 (34) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 35 (14) | 18 (19) | 16 (14) | 1 (3) | |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 15 (6) | 7 (7) | 8 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Other ethnic group | 7 (3) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Parity | 0.229 | ||||

| Never | 189 (77) | 72 (76) | 92 (81) | 25 (69) | |

| Once | 26 (11) | 14 (15) | 6 (5) | 6 (17) | |

| Two times or more | 29 (12) | 9 (9) | 15 (13) | 5 (14) | |

| 11 Food Groups Derived from the European Prospective into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Food Frequency Questionnaire | Factors (Dietary Patterns) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Fats and Oils (grams/day) | 0.838 | ||

| Sugars and Snacks (grams/day) | 0.738 | ||

| Cereals (grams/day) | 0.712 | ||

| Alcoholic beverages (grams/day) | 0.665 | ||

| Red and processed meat (grams/day) | 0.553 | ||

| Fish and Seafood (grams/day) | 0.821 | ||

| Eggs (grams/day) | 0.809 | ||

| Milk and milk products (grams/day) | 0.518 | ||

| Fruits (grams/day) | 0.750 | ||

| Vegetables (grams/day) | 0.747 | ||

| Nuts and Seeds (grams/day) | 0.619 | ||

| Model | Predictor | Coefficient Estimate | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (DP-1) “fats & oils, sugars & snacks, alcoholic beverages, red and processed meat, and cereals” DP | Intercept | 0.419 | <0.001 |

| Stress | 0.003 | 0.005 | |

| Physical activity (METs-h/wk) | −0.0000002 | 0.395 | |

| BMI | 0.002 | 0.062 | |

| Age | −0.003 | 0.004 | |

| Father’s educational level (A-level/higher) | −0.027 | 0.107 | |

| Mother’s educational level (A-level/higher) | −0.006 | 0.713 | |

| Ethnicity (white) | 0.026 | 0.128 | |

| Father’s occupation (other) | 0.015 | 0.369 | |

| Mother’s occupation (other) | 0.022 | 0.174 | |

| Smoking status (smoker) | −0.05 | 0.005 | |

| Participant’s income (above average) | 0.026 | 0.098 | |

| 2 (DP-2) “fish & seafood, eggs, and milk & milk products” DP | Intercept | 0.441 | <0.0001 |

| Stress | −0.002 | 0.14 | |

| Depression | 0.0001 | 0.676 | |

| Mother’s education (A-level/higher) | −0.038 | 0.019 | |

| Father’s occupation (other) | 0.035 | 0.057 | |

| Mother’s occupation (other) | 0.018 | 0.313 | |

| Participant’s income (above average) | 0.033 | 0.069 | |

| 3 (DP-3) “fruits, vegetables, and nuts & seeds” DP | Intercept | 0.653 | <0.001 |

| Stress | −0.005 | <0.001 | |

| Physical activity (METs-h/wk) | 0.0000006 | 0.115 | |

| BMI | −0.005 | 0.001 | |

| Ethnicity (white) | −0.047 | 0.013 | |

| Parent’s income (above average) | 0.023 | 0.184 | |

| Smoking (smoker) | 0.033 | 0.092 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khaled, K.; Hundley, V.; Tsofliou, F. Poor Dietary Quality and Patterns Are Associated with Higher Perceived Stress among Women of Reproductive Age in the UK. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082588

Khaled K, Hundley V, Tsofliou F. Poor Dietary Quality and Patterns Are Associated with Higher Perceived Stress among Women of Reproductive Age in the UK. Nutrients. 2021; 13(8):2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082588

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhaled, Karim, Vanora Hundley, and Fotini Tsofliou. 2021. "Poor Dietary Quality and Patterns Are Associated with Higher Perceived Stress among Women of Reproductive Age in the UK" Nutrients 13, no. 8: 2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082588

APA StyleKhaled, K., Hundley, V., & Tsofliou, F. (2021). Poor Dietary Quality and Patterns Are Associated with Higher Perceived Stress among Women of Reproductive Age in the UK. Nutrients, 13(8), 2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082588