The Double Burden of Malnutrition and Associated Factors among South Asian Adolescents: Findings from the Global School-Based Student Health Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Stunting, Thinness and Overweight

3.2. Prevalence of Health Behaviours

3.3. Factors Associated with Malnutrition Indicators

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, J.N.; Oaks, B.M.; Engle-Stone, R. The Double Burden of Malnutrition: A Systematic Review of Operational Definitions. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet 2020, 395, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Malnutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Hawkes, C.; Ruel, M.T.; Salm, L.; Sinclair, B.; Branca, F. Double-duty actions: Seizing programme and policy opportunities to address malnutrition in all its forms. Lancet 2020, 395, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, R.; Levin, C.; Hale, J.; Hutchinson, B. Economic effects of the double burden of malnutrition. Lancet 2020, 395, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C.; Sawaya, A.L.; Wibaek, R.; Mwangome, M.; Poullas, M.S.; Yajnik, C.S.; Demaio, A. The double burden of malnutrition: Aetiological pathways and consequences for health. Lancet 2020, 395, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrimpton, R.; Rokx, C. The Double Burden of Malnutrition: A Review of Global Evidence; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly. Work Programme of the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition (2016–2025). Available online: https://www.who.int/nutrition/decade-of-action/workprogramme-2016to2025/en/ (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- World Health Organization. Double-Duty Actions for Nutrition. Policy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Nutrition in Adolescence—Issues and Challenges for the Health Sector; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, G.C.; Coffey, C.; Cappa, C.; Currie, D.; Riley, L.; Gore, F.; Degenhardt, L.; Richardson, D.; Astone, N.; Sangowawa, A.O.; et al. Health of the world’s adolescents: A synthesis of internationally comparable data. Lancet 2012, 379, 1665–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleyachetty, R.; Thomas, G.N.; Kengne, A.P.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Schilsky, S.; Khodabocus, J.; Uauy, R. The double burden of malnutrition among adolescents: Analysis of data from the Global School-Based Student Health and Health Behavior in School-Aged Children surveys in 57 low- and middle-income countries. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Improving Child Nutrition: The Achievable Imperative for Global Progress; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Bhurtyal, A.; Wei, J.; Akhtar, P.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Double Burden of Malnutrition and Nutrition Transition in Asia: A Case Study of 4 Selected Countries with Different Socioeconomic Development. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 1663–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashan, M.R.; Das Gupta, R.; Day, B.; Al Kibria, G.M. Differences in prevalence and associated factors of underweight and overweight/obesity according to rural-urban residence strata among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh: Evidence from a cross-sectional national survey. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, T.; Magalhaes, R.J.S.; Townsend, N.; Das, S.K.; Mamun, A. Double Burden of Underweight and Overweight among Women in South and Southeast Asia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, V.S.; Kulkarni, V.S.; Gaiha, R. “Double Burden of Malnutrition”: Reexamining the Coexistence of Undernutrition and Overweight Among Women in India. Int. J. Health Serv. 2017, 47, 108–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herter-Aeberli, I.; Thankachan, P.; Bose, B.; Kurpad, A.V. Increased risk of iron deficiency and reduced iron absorption but no difference in zinc, vitamin A or B-vitamin status in obese women in India. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 2411–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, A.; Angeli, F.; Syamala, T.S.; Van Schayck, C.P.; Dagnelie, P. State-wise dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition among 15-49 year-old women in India: How much does the scenario change considering Asian population-specific BMI cut-off values? Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 618–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafique, S.; Akhter, N.; Stallkamp, G.; de Pee, S.; Panagides, D.; Bloem, M.W. Trends of under- and overweight among rural and urban poor women indicate the double burden of malnutrition in Bangladesh. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 36, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Fahim, S.M.; Islam, M.S.; Biswas, T.; Mahfuz, M.; Ahmed, T. Prevalence and sociodemographic determinants of household-level double burden of malnutrition in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunuwar, D.R.; Singh, D.R.; Pradhan, P.M.S. Prevalence and factors associated with double and triple burden of malnutrition among mothers and children in Nepal: Evidence from 2016 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anik, A.I.; Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Tareque, M.I.; Khan, M.N.; Alam, M.M. Double burden of malnutrition at household level: A comparative study among Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Myanmar. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.M.; Fawzi, W.W.; Barik, A.; Chowdhury, A.; Rai, R.K. Double burden of malnutrition among adolescents in rural West Bengal, India. Nutrition 2020, 79, 110809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, M.; Bhargava, A.; Ghate, S.D.; Rao, R.S.P. Nutritional status of Indian adolescents (15–19 years) from National Family Health Surveys 3 and 4: Revised estimates using WHO 2007 Growth reference. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, W.; Aurino, E.; Penny, M.E.; Behrman, J.R. The double burden of malnutrition among youth: Trajectories and inequalities in four emerging economies. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2019, 34, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faizi, N.; Khan, Z.; Khan, I.M.; Amir, A.; Azmi, S.A.; Khalique, N. A study on nutritional status of school-going adolescents in Aligarh, India. Trop. Dr. 2017, 47, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global School-Based Student Health Survey (GSHS). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/GSHS/ (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- World Health Organization. Growth Reference Data for 5–19 Years. Available online: https://www.who.int/growthref/en/ (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- World Health Organization; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global School-Based Student Health Survey Data User’s Guide; 2013; pp. 1–17. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/gshs/pdf/gshs-data-users-guide.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Christian, P.; Smith, E.R. Adolescent Undernutrition: Global Burden, Physiology, and Nutritional Risks. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 72, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Implementing Effective Actions for Improving Adolescent Nutrition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- de Onis, M.; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; Siyam, A.; Nishida, C.; Siekmann, J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata: Release 13. Statistical Software; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global School-Based Student Health Survey (GSHS). Available online: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/datasets/en/ (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health Website. Physical Activity and Young People. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/physical-activity/physical-activity-and-young-people (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- American Dental Association. American Dental Association Statement on Regular Brushing and Flossing to Help Prevent Oral Infections. Available online: https://www.ada.org/en/press-room/news-releases/2013-archive/august/american-dental-association-statement-on-regular-brushing-and-flossing-to-help-prevent-oral (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Ahmad, S.; Shukla, N.K.; Singh, J.V.; Shukla, R.; Shukla, M. Double burden of malnutrition among school-going adolescent girls in North India: A cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Onis, M.; Borghi, E.; Arimond, M.; Webb, P.; Croft, T.; Saha, K.; De-Regil, L.M.; Thuita, F.; Heidkamp, R.; Krasevec, J.; et al. Prevalence thresholds for wasting, overweight and stunting in children under 5 years. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estecha Querol, S.; Gill, P.; Iqbal, R.; Kletter, M.; Ozdemir, N.; Al-Khudairy, L. Adolescent undernutrition in South Asia: A scoping review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, S.K.; Puthussery, S. Risk factors of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence in South Asian countries: A systematic review of the evidence. Public Health 2015, 129, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.; Binder, G.; Humphries-Waa, K.; Tidhar, T.; Cini, K.; Comrie-Thomson, L.; Vaughan, C.; Francis, K.; Scott, N.; Wulan, N.; et al. Gender inequalities in health and wellbeing across the first two decades of life: An analysis of 40 low-income and middle-income countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1473–e1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikree, F.F.; Pasha, O. Role of gender in health disparity: The South Asian context. BMJ 2004, 328, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2016; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Adolescent and Women’s Nutrition. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/what-we-do/nutrition/adolescent-and-womens-nutrition (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Yang, L.; Bovet, P.; Ma, C.; Zhao, M.; Liang, Y.; Xi, B. Prevalence of underweight and overweight among young adolescents aged 12-15 years in 58 low-income and middle-income countries. Pediatric Obes. 2019, 14, e12468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleyachetty, R.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Tait, C.A.; Schilsky, S.; Forrester, T.; Kengne, A.P. Prevalence of behavioural risk factors for cardiovascular disease in adolescents in low-income and middle-income countries: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, H.; Viswanathan, B.; Rousson, V.; Paccaud, F.; Bovet, P. Association between substance use and psychosocial characteristics among adolescents of the Seychelles. BMC Pediatr. 2011, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shayo, F.K.; Lawala, P.S. Does food insecurity link to suicidal behaviors among in-school adolescents? Findings from the low-income country of sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panter-Brick, C.; Eggerman, M.; Gonzalez, V.; Safdar, S. Violence, suffering, and mental health in Afghanistan: A school-based survey. Lancet 2009, 374, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Alcohol Use and Misuse Among School-Going Adolescents in Thailand: Results of a National Survey in 2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Hygiene behaviour and associated factors among in-school adolescents in nine African countries. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2011, 18, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, M.; Ma, C.; Bovet, P. Tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in young adolescents aged 12–15 years: Data from 68 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e795–e805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Aslam, S.K.; Zaheer, S.; Shafique, K. Anti-smoking initiatives and current smoking among 19,643 adolescents in South Asia: Findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey. Harm Reduct. J. 2014, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, G.; Sun, N.; Li, L.; Qi, W.; Li, C.; Zhou, M.; Chen, Z.; Han, L. Physical behaviors of 12–15 year-old adolescents in 54 low- and middle-income countries: Results from the Global School-based Student Health Survey. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 010423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Oral and hand hygiene behaviour and risk factors among in-school adolescents in four Southeast Asian countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 2780–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Butler, L.; Tully, M.A.; Jacob, L.; Barnett, Y.; López-Sánchez, G.F.; López-Bueno, R.; Shin, J.I.; McDermott, D.; Pfeifer, B.A.; et al. Hand-Washing Practices among Adolescents Aged 12–15 Years from 80 Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauter, S.R.; Kim, L.P.; Jacobsen, K.H. Loneliness and friendlessness among adolescents in 25 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 25, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltzer, K. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among school children in six African countries. Int. J. Psychol. 2009, 44, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Prevalence and Correlates of Physical Fighting Among School Going Students Aged 13–15 in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Member States. Iran J. Pediatr. 2017, 27, e8170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdirahman, H.A.; Bah, T.T.; Shrestha, H.L.; Jacobsen, K.H. Bullying, mental health, and parental involvement among adolescents in the Caribbean. West Indian Med. J. 2012, 61, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushal, S.A.; Amin, Y.M.; Reza, S.; Shawon, M.S.R. Parent-adolescent relationships and their associations with adolescent suicidal behaviours: Secondary analysis of data from 52 countries using the Global School-based Health Survey. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 31, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kroon, J.; Lalloo, R.; Kulkarni, S.; Johnson, N.W. Relationship between body mass index and dental caries in children, and the influence of socio-economic status. Int. Dent. J. 2017, 67, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.; Päkkilä, J.; Ryhänen, T.; Laitala, M.-L.; Humagain, M.; Ojaniemi, M.; Anttonen, V. Body mass index and dental caries experience in Nepalese schoolchildren. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2019, 47, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravathy, K.P.; Thippeswamy, H.M.; Kumar, N.; Chenna, D. Relationship of body mass index and dental caries with oral health related quality of life among adolescents of Udupi district, South India. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2013, 14, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Sethi, V.; Nagargoje, V.P.; Saraswat, A.; Surani, N.; Agarwal, N.; Bhatia, V.; Ruikar, M.M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Parhi, R.N.; et al. WASH practices and its association with nutritional status of adolescent girls in poverty pockets of eastern India. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godakanda, I.; Abeysena, C.; Lokubalasooriya, A. Sedentary behavior during leisure time, physical activity and dietary habits as risk factors of overweight among school children aged 14–15 years: Case control study. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, E.; Larsen, J.K.; Kremers, S.; Dagnelie, P.; Geenen, R. Peer influence on snacking behavior in adolescence. Appetite 2010, 55, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.; Dennison, C. Influences on adolescent food choice. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1996, 55, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, A.W.; Lovato, C.Y.; Barr, S.I.; Hanning, R.M.; Mâsse, L.C. A qualitative study exploring how school and community environments shape the food choices of adolescents with overweight/obesity. Appetite 2015, 95, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Overweight, obesity and associated factors among 13–15 years old students in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Member Countries, 2007–2014. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2016, 47, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Underweight and overweight or obesity and associated factors among school-going adolescents in five ASEAN countries, 2015. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019, 13, 3075–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, R.; Ranasinghe, P.; Wijayabandara, M.; Hills, A.P.; Misra, A. Nutrition Transition and Obesity Among Teenagers and Young Adults in South Asia. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2017, 13, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, N.; Khubchandani, J.; Seabert, D.; Nimkar, S. Overweight status in Indian children: Prevalence and psychosocial correlates. Indian Pediatr. 2015, 52, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Choudhuri, D.; Balaram, S. Factors Associated with Nutritional Status of Adolescent Schoolchildren in Tripura. Indian Pediatr. 2020, 57, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengma, M.S.; Bose, K.; Mondal, N. Socio-economic and demographic correlates of stunting among adolescents of Assam, North-east India. Anthropol. Rev. 2016, 79, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.P.; Pari, A.K.; Sinha, A.; Dhara, P.C. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors: A cross-sectional study among rural adolescents in West Bengal, India. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2017, 4, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osendarp, S.J.M.; Brown, K.H.; Neufeld, L.M.; Udomkesmalee, E.; Moore, S.E. The double burden of malnutrition-further perspective. Lancet 2020, 396, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.E.; Roberts, A.L.; Perloe, A.; Bainivualiku, A.; Richards, L.K.; Gilman, S.E.; Striegel-Moore, R.H. Youth health-risk behavior assessment in Fiji: The reliability of Global School-based Student Health Survey content adapted for ethnic Fijian girls. Ethn. Health 2010, 15, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, R.; Dastgiri, S.; Soares, J.; Baybordi, E.; Zeinalzadeh, A.; Asl Rahimi, V.; Mohammadi, R. Reliability and Validity of the Persian Version of Global School-based Student Health Survey Adapted for Iranian School Students. J. Clin. Res. Gov. 2014, 3, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Survey Year | Response Rate (%) 1 | Sample Size | Girls (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | 2009 | 76 | 4998 | 25.1 |

| Afghanistan | 2014 | 79 | 1493 | 63.2 |

| Bangladesh | 2014 | 91 | 2753 | 61.6 |

| India | 2007 | 83 | 7327 | 45.3 |

| Maldives | 2009 | 80 | 1977 | 56.2 |

| Nepal | 2015 | 70 | 4615 | 54.9 |

| Sri Lanka | 2016 | 89 | 2228 | 56.6 |

| Bhutan | 2016 | 95 | 3287 | 58.1 |

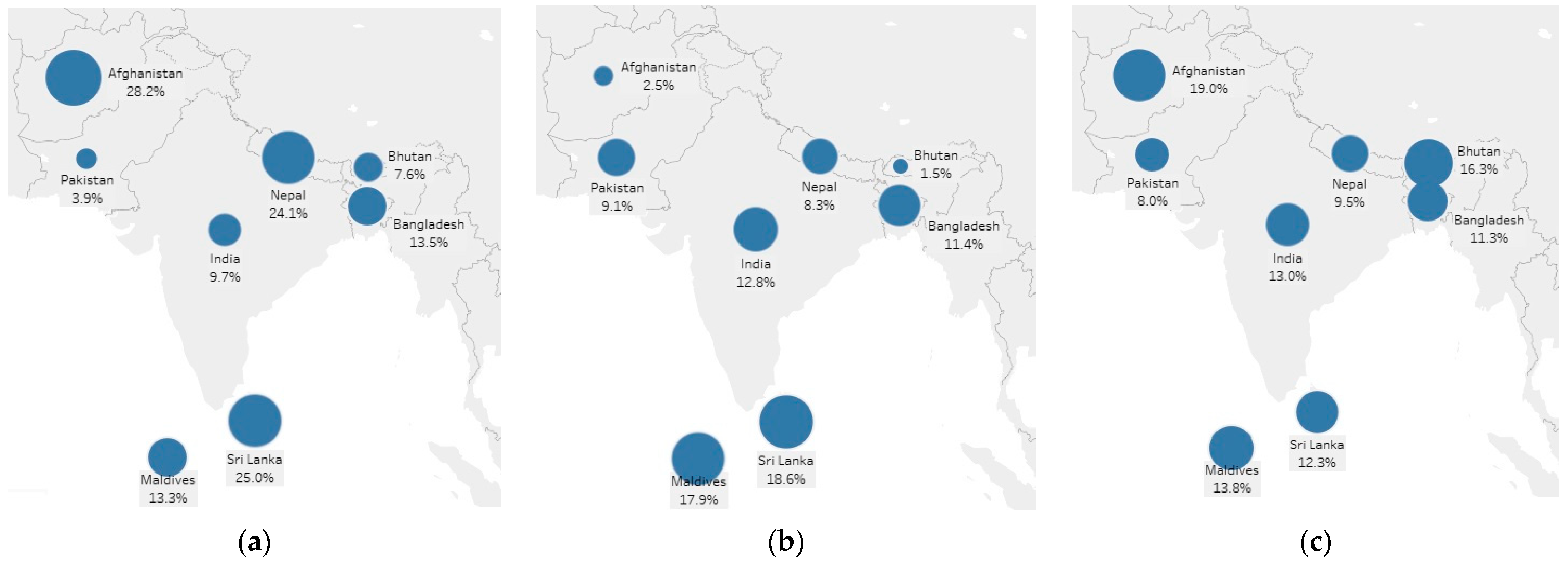

| Country | Stunting (Height-for-Age < 2 SDs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Students (%) | Boys (%) | Girls (%) | χ2 (p-Value) 1 | |

| Pakistan | 3.90 | 2.32 | 6.34 | 49.43 (0.000) |

| Afghanistan | 28.15 | 35.97 | 19.82 | 38.44 (0.071) |

| Bangladesh | 13.52 | 12.53 | 15.14 | 3.42 (0.460) |

| India | 9.65 | 8.60 | 11.07 | 10.45 (0.198) |

| Maldives | 13.33 | 12.13 | 14.39 | 1.26 (0.543) |

| Nepal | 24.09 | 24.45 | 23.77 | 0.25 (0.592) |

| Sri Lanka | 24.99 | 25.49 | 24.57 | 0.11 (0.843) |

| Bhutan | 7.58 | 7.90 | 7.32 | 0.37 (0.662) |

| South Asia | 12.97 | 11.64 | 14.80 | 51.60 (0.059) |

| Country | Thinness (BMI-for-Age < 2 SDs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Students (%) | Boys (%) | Girls (%) | χ2 (p-Value) 1 | |

| Pakistan | 9.09 | 9.51 | 8.43 | 1.59 (0.575) |

| Afghanistan | 2.51 | 2.34 | 2.69 | 0.15 (0.781) |

| Bangladesh | 11.43 | 12.83 | 9.13 | 7.89 (0.262) |

| India | 12.82 | 13.48 | 11.92 | 3.26 (0.263) |

| Maldives | 17.86 | 16.73 | 18.86 | 0.89 (0.521) |

| Nepal | 8.25 | 9.78 | 6.93 | 10.84 (0.029) |

| Sri Lanka | 18.56 | 20.14 | 17.22 | 1.41 (0.369) |

| Bhutan | 1.49 | 2.02 | 1.05 | 5.07 (0.001) |

| South Asia | 10.78 | 11.85 | 9.29 | 39.80 (0.109) |

| Country | Overweight (BMI-for-Age > 1 SDs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Students (%) | Boys (%) | Girls (%) | χ2 (p-Value) 1 | |

| Pakistan | 7.98 | 6.48 | 10.31 | 22.96 (0.001) |

| Afghanistan | 19.04 | 21.25 | 16.69 | 4.01 (0.333) |

| Bangladesh | 11.3 | 12.71 | 8.99 | 8.03 (0.292) |

| India | 12.96 | 14.36 | 11.05 | 14.57 (0.010) |

| Maldives | 13.77 | 18.33 | 9.74 | 17.80 (0.020) |

| Nepal | 9.53 | 10.81 | 8.43 | 6.63 (0.151) |

| Sri Lanka | 13.22 | 13.94 | 12.6 | 0.39 (0.580) |

| Bhutan | 16.34 | 12.89 | 19.16 | 22.84 (0.002) |

| South Asia | 10.77 | 11.43 | 9.87 | 14.84 (0.352) |

| Pakistan (%) | Afghanistan (%) | Bangladesh (%) | India (%) | Maldives (%) | Nepal (%) | Sri Lanka (%) | Bhutan (%) | South Asia (%) | χ2 (p-Value) 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 fruits/vegs per day | 9.84 | 15.35 | 16.32 | 14.81 | 11.39 | 9.01 | 23.67 | 23.53 | 14.33 | 401.75 (0.000) |

| Loneliness | 11.87 | 28.83 | 10.90 | 8.23 | 13.87 | 5.89 | 7.49 | 11.38 | 10.07 | 337.99 (0.000) |

| Anxiety | 8.21 | 21.84 | 4.47 | 7.61 | 13.22 | 3.83 | 3.87 | 6.88 | 5.91 | 413.56 (0.000) |

| Tobacco use | 6.30 | 6.52 | 6.90 | 1.22 | 8.99 | 4.90 | 2.49 | 19.29 | 5.33 | 273.97 (0.004) |

| Physically activity | 11.57 | 9.64 | 41.24 | 30.07 | 21.61 | 14.42 | 17.36 | 15.54 | 27.14 | 2385.96 (0.000) |

| Active transportation | 61.48 | 70.16 | 67.86 | 56.70 | 52.41 | 57.94 | 60.79 | 45.94 | 62.93 | 259.43 (0.004) |

| Sedentary behaviour | 8.19 | 23.34 | 14.93 | 22.84 | 42.45 | 9.78 | 35.08 | 28.06 | 15.83 | 1199.93 (0.000) |

| Tooth brushing | 30.18 | 41.08 | 64.09 | 55.58 | 77.06 | 49.61 | 71.19 | 42.96 | 53.97 | 2151.41 (0.000) |

| Washing hands before meals | 96.55 | 93.97 | 96.90 | 94.08 | 91.46 | 96.00 | 97.33 | 96.19 | 96.25 | 88.10 (0.066) |

| Washing hands after toilet | 96.59 | 94.38 | 98.06 | 96.68 | 95.32 | 95.59 | 97.08 | 95.71 | 97.05 | 90.24 (0.213) |

| Washing hands with soap | 91.97 | 88.37 | 95.04 | 87.02 | 92.76 | 95.15 | 92.94 | 94.71 | 92.93 | 359.35 (0.001) |

| Friendships | 91.89 | 86.25 | 91.20 | 89.83 | 90.48 | 95.57 | 94.75 | 90.46 | 91.94 | 150.86 (0.000) |

| Peer support | 39.36 | 63.09 | 55.41 | 41.53 | 51.41 | 53.46 | 49.89 | 39.98 | 49.38 | 562.33 (0.000) |

| Parental involvement in school | 52.36 | 45.55 | 53.70 | 47.66 | 31.60 | 50.16 | 68.45 | 30.50 | 52.98 | 308.76 (0.000) |

| Parental understanding | 54.64 | 51.97 | 47.67 | 62.39 | 35.16 | 53.75 | 63.17 | 42.44 | 53.44 | 377.37 (0.000) |

| Parental bonding | 50.47 | 54.72 | 43.54 | 57.38 | 48.77 | 50.47 | 70.29 | 39.46 | 50.33 | 647.34 (0.000) |

| Stunting FULL MODEL | Stunting REDUCED MODEL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Bootstrap Std.Err. | z | p | 95% Conf. Interval | OR | Bootstrap Std.Err. | z | p | 95% Conf. Interval | |||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 12 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 13 years | 1.93 | 0.35 | 3.62 | 0.000 | 1.35 | 2.75 | 1.96 | 0.36 | 3.71 | 0.000 | 1.37 | 2.80 |

| 14 years | 2.71 | 0.61 | 4.45 | 0.000 | 1.75 | 4.20 | 2.66 | 0.59 | 4.41 | 0.000 | 1.72 | 4.11 |

| 15 years | 3.33 | 0.70 | 5.74 | 0.000 | 2.21 | 5.03 | 3.27 | 0.66 | 5.83 | 0.000 | 2.20 | 4.87 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Boy | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Girl | 1.15 | 0.20 | 0.81 | 0.416 | 0.82 | 1.60 | 1.19 | 0.18 | 1.14 | 0.254 | 0.88 | 1.61 |

| Country | ||||||||||||

| Pakistan | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Afghanistan | 11.80 | 3.89 | 7.48 | 0.000 | 6.18 | 22.53 | 10.67 | 3.14 | 8.05 | 0.000 | 6.00 | 19.00 |

| Bangladesh | 4.85 | 1.31 | 5.86 | 0.000 | 2.86 | 8.23 | 4.29 | 1.09 | 5.73 | 0.000 | 2.61 | 7.07 |

| India | 2.97 | 0.67 | 4.84 | 0.000 | 1.91 | 4.61 | 2.73 | 0.60 | 4.60 | 0.000 | 1.78 | 4.19 |

| Maldives | 3.62 | 1.13 | 4.11 | 0.000 | 1.96 | 6.68 | 3.24 | 0.89 | 4.31 | 0.000 | 1.90 | 5.54 |

| Nepal | 9.01 | 2.05 | 9.66 | 0.000 | 5.77 | 14.08 | 8.99 | 2.02 | 9.77 | 0.000 | 5.79 | 13.97 |

| Sri Lanka | 8.96 | 2.00 | 9.85 | 0.000 | 5.79 | 13.87 | 8.30 | 1.81 | 9.68 | 0.000 | 5.41 | 12.73 |

| Bhutan | 2.39 | 0.52 | 4.04 | 0.000 | 1.57 | 3.65 | 2.21 | 0.45 | 3.88 | 0.000 | 1.48 | 3.29 |

| 5 fruits and vegs | ||||||||||||

| <5 per day | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 5 or more per day | 0.90 | 0.16 | −0.60 | 0.548 | 0.63 | 1.27 | ||||||

| Loneliness | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.85 | 0.17 | −0.81 | 0.417 | 0.58 | 1.26 | ||||||

| Anxiety | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.93 | 0.18 | −0.38 | 0.704 | 0.63 | 1.36 | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||||||||

| 0 days | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 1 or more days | 0.54 | 0.22 | −1.51 | 0.132 | 0.24 | 1.21 | 0.52 | 0.18 | −1.90 | 0.058 | 0.26 | 1.02 |

| Physically activity | ||||||||||||

| <7 days per week | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 7 days per week | 0.85 | 0.12 | −1.13 | 0.257 | 0.64 | 1.13 | ||||||

| Active transportation | ||||||||||||

| <3 days per week | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3 or more days per week | 1.00 | 0.14 | −0.03 | 0.978 | 0.76 | 1.30 | ||||||

| Sedentary behaviour | ||||||||||||

| <3 h per day | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3 or more hours per day | 0.78 | 0.14 | −1.35 | 0.176 | 0.55 | 1.12 | ||||||

| Tooth brushing | ||||||||||||

| <2 times per day | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2 times or more per day | 0.90 | 0.07 | −1.28 | 0.201 | 0.77 | 1.06 | ||||||

| Washing hands before meals | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sometimes/often/always | 1.46 | 0.29 | 1.89 | 0.059 | 0.99 | 2.17 | 1.33 | 0.24 | 1.57 | 0.118 | 0.93 | 1.89 |

| Washing hands after toilet | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Sometimes/often/always | 1.10 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.708 | 0.67 | 1.79 | ||||||

| Washing hands with soap | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Sometimes/often/always | 1.05 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.767 | 0.76 | 1.46 | ||||||

| Friendships | ||||||||||||

| no friends | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 1 or more friend | 0.85 | 0.15 | −0.92 | 0.358 | 0.59 | 1.21 | ||||||

| Peer support | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.76 | 0.07 | −3.15 | 0.002 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.06 | −3.45 | 0.001 | 0.64 | 0.88 |

| Parental involvement in school | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.95 | 0.10 | −0.45 | 0.656 | 0.78 | 1.17 | ||||||

| Parental understanding | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 1.09 | 0.12 | 0.80 | 0.426 | 0.88 | 1.34 | ||||||

| Parental bonding | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 1.03 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.825 | 0.78 | 1.36 | ||||||

| Thinness FULL MODEL | Thinness REDUCED MODEL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Bootstrap Std.Err. | z | p | 95% Conf. Interval | OR | Bootstrap Std.Err. | z | p | 95% Conf. Interval | |||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 12 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 13 years | 1.86 | 0.33 | 3.49 | 0.000 | 1.31 | 2.64 | 1.65 | 0.27 | 3.02 | 0.003 | 1.19 | 2.28 |

| 14 years | 1.36 | 0.25 | 1.69 | 0.090 | 0.95 | 1.94 | 1.25 | 0.22 | 1.23 | 0.218 | 0.88 | 1.77 |

| 15 years | 1.26 | 0.26 | 1.13 | 0.259 | 0.84 | 1.88 | 1.16 | 0.21 | 0.78 | 0.433 | 0.81 | 1.66 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Boy | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Girl | 0.79 | 0.13 | −1.46 | 0.143 | 0.58 | 1.08 | 0.76 | 0.11 | −1.81 | 0.070 | 0.57 | 1.02 |

| Country | ||||||||||||

| Pakistan | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Afghanistan | 0.27 | 0.09 | −4.07 | 0.000 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.08 | −4.54 | 0.000 | 0.17 | 0.50 |

| Bangladesh | 1.57 | 0.51 | 1.39 | 0.165 | 0.83 | 2.97 | 1.48 | 0.46 | 1.25 | 0.211 | 0.80 | 2.73 |

| India | 1.93 | 0.34 | 3.72 | 0.000 | 1.36 | 2.73 | 1.71 | 0.28 | 3.24 | 0.001 | 1.24 | 2.37 |

| Maldives | 3.21 | 0.72 | 5.17 | 0.000 | 2.06 | 4.99 | 3.09 | 0.63 | 5.53 | 0.000 | 2.07 | 4.62 |

| Nepal | 1.10 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.622 | 0.76 | 1.58 | 0.99 | 0.17 | −0.06 | 0.956 | 0.71 | 1.39 |

| Sri Lanka | 3.25 | 0.68 | 5.65 | 0.000 | 2.16 | 4.88 | 2.99 | 0.60 | 5.50 | 0.000 | 2.02 | 4.42 |

| Bhutan | 0.18 | 0.05 | −6.38 | 0.000 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.05 | −6.66 | 0.000 | 0.11 | 0.30 |

| 5 fruits and vegs | ||||||||||||

| <5 per day | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 5 or more per day | 0.86 | 0.13 | −1.02 | 0.309 | 0.65 | 1.15 | ||||||

| Loneliness | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 1.19 | 0.21 | 0.97 | 0.332 | 0.84 | 1.68 | ||||||

| Anxiety | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.99 | 0.16 | −0.07 | 0.942 | 0.71 | 1.37 | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||||||||

| 0 days | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 1 or more days | 1.37 | 0.34 | 1.27 | 0.203 | 0.84 | 2.21 | ||||||

| Physically activity | ||||||||||||

| <7 days per week | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 7 days per week | 0.92 | 0.13 | −0.57 | 0.567 | 0.71 | 1.21 | ||||||

| Active transportation | ||||||||||||

| <3 days per week | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3 or more days per week | 1.15 | 0.10 | 1.59 | 0.111 | 0.97 | 1.35 | ||||||

| Sedentary behaviour | ||||||||||||

| <3 h per day | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3 or more hours per day | 0.63 | 0.10 | −2.92 | 0.004 | 0.46 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.09 | −3.28 | 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.82 |

| Tooth brushing | ||||||||||||

| <2 times per day | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2 times or more per day | 0.70 | 0.12 | −2.16 | 0.031 | 0.50 | 0.97 | 0.72 | 0.09 | −2.61 | 0.009 | 0.56 | 0.92 |

| Washing hands before meals | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Sometimes/often/always | 1.02 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.945 | 0.61 | 1.70 | ||||||

| Washing hands after toilet | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Sometimes/often/always | 1.07 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.802 | 0.63 | 1.81 | ||||||

| Washing hands with soap | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Sometimes/often/always | 1.14 | 0.30 | 0.52 | 0.606 | 0.69 | 1.90 | ||||||

| Friendships | ||||||||||||

| no friends | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 1 or more friend | 0.98 | 0.20 | −0.10 | 0.918 | 0.66 | 1.45 | ||||||

| Peer support | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.94 | 0.07 | −0.73 | 0.467 | 0.81 | 1.10 | ||||||

| Parental involvement in school | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.95 | 0.11 | −0.41 | 0.684 | 0.76 | 1.19 | ||||||

| Parental understanding | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 1.09 | 0.11 | 0.92 | 0.356 | 0.90 | 1.32 | ||||||

| Parental bonding | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.89 | 0.08 | −1.28 | 0.202 | 0.74 | 1.07 | ||||||

| Overweight FULL MODEL | Overweight REDUCED MODEL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Bootstrap Std.Err. | z | p | 95% Conf. Interval | OR | Bootstrap Std.Err. | z | p | 95% Conf. Interval | |||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 12 years | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 13 years | 0.58 | 0.10 | −3.25 | 0.001 | 0.42 | 0.81 | 0.61 | 0.11 | −2.75 | 0.006 | 0.42 | 0.87 |

| 14 years | 0.53 | 0.09 | −3.58 | 0.000 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.53 | 0.10 | −3.48 | 0.001 | 0.37 | 0.76 |

| 15 years | 0.47 | 0.10 | −3.49 | 0.000 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.10 | −3.37 | 0.001 | 0.31 | 0.73 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Boy | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Girl | 0.72 | 0.14 | −1.69 | 0.091 | 0.49 | 1.05 | 0.74 | 0.13 | −1.67 | 0.094 | 0.52 | 1.05 |

| Country | ||||||||||||

| Pakistan | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Afghanistan | 2.63 | 0.57 | 4.47 | 0.000 | 1.72 | 4.03 | 2.64 | 0.51 | 5.02 | 0.000 | 1.81 | 3.86 |

| Bangladesh | 1.27 | 0.36 | 0.84 | 0.401 | 0.73 | 2.22 | 1.31 | 0.38 | 0.92 | 0.356 | 0.74 | 2.32 |

| India | 1.45 | 0.26 | 2.06 | 0.039 | 1.02 | 2.06 | 1.46 | 0.24 | 2.33 | 0.020 | 1.06 | 2.02 |

| Maldives | 1.45 | 0.35 | 1.54 | 0.123 | 0.90 | 2.32 | 1.65 | 0.37 | 2.23 | 0.026 | 1.06 | 2.57 |

| Nepal | 0.96 | 0.19 | −0.21 | 0.835 | 0.65 | 1.41 | 0.97 | 0.19 | −0.14 | 0.886 | 0.66 | 1.42 |

| Sri Lanka | 1.53 | 0.33 | 1.95 | 0.051 | 1.00 | 2.33 | 1.59 | 0.35 | 2.11 | 0.035 | 1.03 | 2.44 |

| Bhutan | 2.23 | 0.37 | 4.77 | 0.000 | 1.60 | 3.10 | 2.23 | 0.34 | 5.25 | 0.000 | 1.65 | 3.01 |

| 5 fruits and vegs | ||||||||||||

| <5 per day | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 5 or more per day | 0.84 | 0.17 | −0.87 | 0.384 | 0.57 | 1.24 | ||||||

| Loneliness | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 1.07 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.688 | 0.76 | 1.52 | ||||||

| Anxiety | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.63 | 0.09 | −3.07 | 0.002 | 0.47 | 0.85 | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||||||||

| 0 days | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 1 or more days | 0.45 | 0.12 | −3.00 | 0.003 | 0.27 | 0.76 | 0.44 | 0.11 | −3.34 | 0.001 | 0.27 | 0.71 |

| Physically activity | ||||||||||||

| <7 days per week | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 7 days per week | 0.93 | 0.19 | −0.34 | 0.734 | 0.63 | 1.38 | ||||||

| Active transportation | ||||||||||||

| <3 days per week | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3 or more days per week | 1.01 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.925 | 0.77 | 1.34 | ||||||

| Sedentary behaviour | ||||||||||||

| <3 h per day | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3 or more hours per day | 1.29 | 0.21 | 1.56 | 0.118 | 0.94 | 1.78 | ||||||

| Tooth brushing | ||||||||||||

| <2 times per day | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2 times or more per day | 1.50 | 0.21 | 2.99 | 0.003 | 1.15 | 1.97 | 1.43 | 0.17 | 2.96 | 0.003 | 1.13 | 1.82 |

| Washing hands before meals | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Sometimes/often/always | 1.11 | 0.26 | 0.46 | 0.648 | 0.71 | 1.74 | ||||||

| Washing hands after toilet | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 1.13 | 0.28 | 0.51 | 0.612 | 0.70 | 1.83 | ||||||

| Washing hands with soap | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sometimes/often/always | 1.59 | 0.32 | 2.30 | 0.021 | 1.07 | 2.37 | 1.58 | 0.31 | 2.31 | 0.021 | 1.07 | 2.33 |

| Friendships | ||||||||||||

| no friends | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 1 or more friend | 0.85 | 0.16 | −0.89 | 0.375 | 0.59 | 1.22 | ||||||

| Peer support | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 1.00 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.996 | 0.79 | 1.26 | ||||||

| Parental involvement in school | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.80 | 0.10 | −1.74 | 0.081 | 0.63 | 1.03 | 0.80 | 0.08 | −2.21 | 0.027 | 0.66 | 0.98 |

| Parental understanding | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.982 | 0.75 | 1.34 | ||||||

| Parental bonding | ||||||||||||

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Often/always | 0.99 | 0.09 | −0.14 | 0.891 | 0.83 | 1.17 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estecha Querol, S.; Iqbal, R.; Kudrna, L.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Gill, P. The Double Burden of Malnutrition and Associated Factors among South Asian Adolescents: Findings from the Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082867

Estecha Querol S, Iqbal R, Kudrna L, Al-Khudairy L, Gill P. The Double Burden of Malnutrition and Associated Factors among South Asian Adolescents: Findings from the Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Nutrients. 2021; 13(8):2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082867

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstecha Querol, Sara, Romaina Iqbal, Laura Kudrna, Lena Al-Khudairy, and Paramijit Gill. 2021. "The Double Burden of Malnutrition and Associated Factors among South Asian Adolescents: Findings from the Global School-Based Student Health Survey" Nutrients 13, no. 8: 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082867

APA StyleEstecha Querol, S., Iqbal, R., Kudrna, L., Al-Khudairy, L., & Gill, P. (2021). The Double Burden of Malnutrition and Associated Factors among South Asian Adolescents: Findings from the Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Nutrients, 13(8), 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082867