Adherence to the Mediterranean-Style Eating Pattern and Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

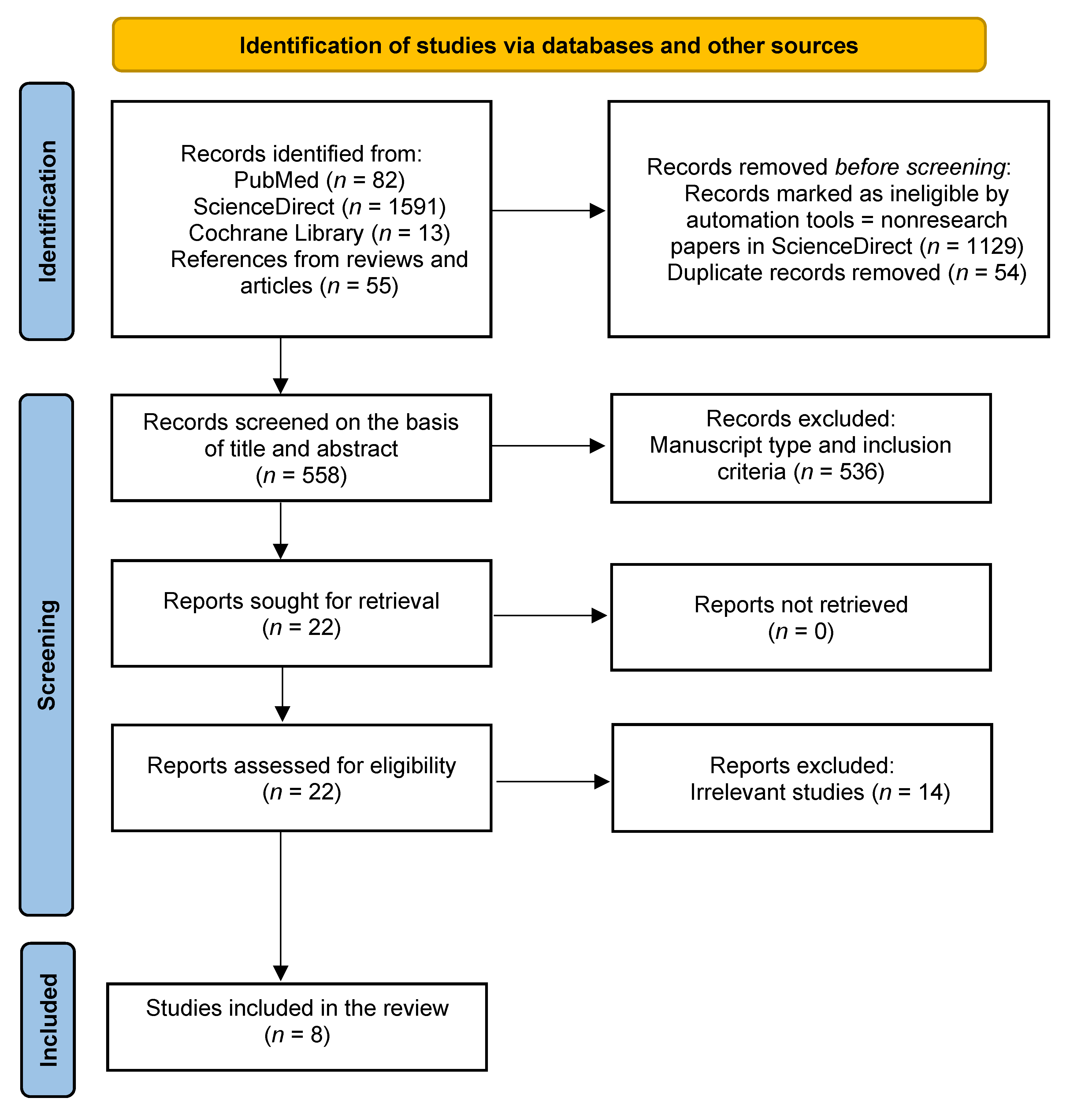

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Search Strategy

2.2. Assessment of Quality

3. Results

3.1. Search Outcomes and Study Quality Assessment

3.2. Details and Characteristics of the Studies

| Article Country Study Name and Design | Period of Data Collection Sample Size Age and Sex | Exposure and Outcome Assessments | Outcome and Compared Variables | Adjusted Confounders | OR or HR (95% CI) and p-Value | Study Quality | Notes (See Main Text for Further Comments) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| › Mares et al. 2011 [36] › USA › CAREDS: cross-sectional nested in WHIOS (prospective) | › CAREDS baseline: 2001–2004; WHIOS baseline: 1994–1998 › 1313 › 55–74 › F | › Validated, semiquantitative FFQ at WHIOS baseline (122 items) › aMED score (0–9) › aMED quartiles: Q1 = 0–1; Q2 = 2–3; Q3 = 4–5; Q4 = 6–9 › Fundus stereoscopic photography › AMD grading based on a modified Wisconsin grading classification | › Early AMD in at least one eye (n = 187) › aMED Q4 (n = 53) vs. aMED Q1 (n = 490) | (a) Model 1: age, pack-years smoked, history of diabetes, AMD, CVD and HRT, and iris colour (b) Model 2: further adjustment for physical activity | › Model 1: OR = 0.34 (0.08–0.98) p = 0.046 › Model 2: OR = 0.44 (0.10–1.27) p = 0.23 | High (8) | › Selected participantshad intakes of lutein plus zeaxanthin that were above the 78th and below the 28th percentiles › aMED Q4: small sample size › Evaluation of the diet using the HEI showed similar results |

| › Merle et al. 2015 [48] › USA › Prospective cohort within AREDS (RCT) | › 13 years (enrolment 1992–1998) › 2525 › 55–80 at baseline › M and F | › Validated, self-administered, semiquantitative FFQ (90 items) at AREDS baseline › aMED score (0–9) › aMED tertiles: T1 = low (0–3), T2 = medium (4–5), T3 = high (6–9) › Retinal stereoscopic images › AMD grading at baseline based on the CARMS system | › Progression to advanced AMD (n = 1028) › aMED T3 (n = 676) vs. aMED T1 (n = 852) | › Model 1: age, sex, AREDS treatment, AMD grade at baseline, TEI › Model 2: further adjustment for education, smoking history, BMI, supplement use, and 10 genetic variants (SNPs) | › Model 1: HR = 0.74 (0.61–0.90) p = 0.005 › Model 2: HR = 0.74 (0.61–0.91) p = 0.007 | High (7) | › Evaluation of the interaction between aMED score and genetic variations on risk of AMD (10 SNPs analysed in 7 different genes) › Fish and vegetable consumption was associated with lower odds of progression |

| › Hogg et al. 2017 [45] › Europe (Norway, Estonia, UK, France, Italy, Greece, Spain) › Cross-sectional, within EUREYE study (cross-sectional study with retrospective and current exposure measurements) | › 2001–2002 › 4753 › Mean age = 73.2 ± 5.6 years › M and F | › Semiquantitative FFQ (130 goods) tailored to each country › MDS (0–9) from Martinez-Gonzalez et al. 2004 › MDS score quartiles: Q1 = ≤ 4, Q2 = 5, Q3 = 6, and Q4 = > 6 › Full eye examination and stereoscopic colour fundus digital photography › AMD graded according to the ICS for age-related maculopathy | › Presence of AMD: early (n = 2333), large drusen (n = 641), GA (n = 49), nvAMD (n = 109); control (n = 2262) › Q4 (n = 199) vs. Q1 (n = 787) | › Model 1: unadjusted › Model 2: age, sex, country, education, smoking, drinking, history of CVD, aspirin consumption, and diabetes | › Model 1: Early AMD OR = 0.94 (0.85–1.03) p = 0.4 Large drusen OR = 0.79 (0.65–0.97) p = 0.05 nvAMD OR 0.52 (0.29–0.93) p = 0.03 › Model 2: Early AMD OR = 0.96 (0.83–1.11) p = 0.9 Large drusen OR = 0.80 (0.65–0.98) p = 0.1 nvAMD OR = 0.53 (0.27–1.04) p = 0.01 | High (9) | › No association between MDS and prevalence of GA |

| › Nunes et al. 2018 [46] › Portugal › Nested case-control study within the “Epidemiologic Study of the Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Portugal: The Coimbra Eye Study” (cross-sectional) [54] | › 2012–2014 (Coimbra study = 2009–2011) › 1992 › >55 years › M and F | › Validated FFQ (86 items) › mediSCORE (0–9); high adherence = ≥6 › Complete ophthalmological examination and digital mydriatic colour fundus photography › AMD graded according to the ICS for age-related maculopathy (as in Hogg et al. 2016) | › AMD: case group = 768 (control = 1224, age and sex-matched) › High mediSCORE vs. prevalence of AMD | › Age, sex, BMI, abdominal perimeter, physical activity, smoking status, diabetes, and hypertension | › OR = 0.73 (0.58–0.93) p = 0.009 | High (7) | › Food group analysis: higher consumption of vegetables reduced odds of AMD onset by 36% (OR = 0.63 (0.52–0.76), p < 0.001), and higher intake of nuts and fruits lowered odds by 21% (OR = 0.78, (0.65–0.94), p = 0.010) › Cases were significantly older |

| › Raimundo et al. 2018 [47] › Portugal › Nested case-control study within the “Epidemiologic Study of the Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Portugal: The Coimbra Eye Study” (cross-sectional) | › 2012–2014 (Coimbra study = 2009–2011) › 883 › >55 years › M and F | › Same as Nunes et al. 2018 | › AMD: case group = 434 (control = 449, age and sex-matched) › High mediSCORE vs. prevalence of AMD | › Age, sex, smoking, calories consumption | › OR = 0.62 (0.38–0.97) p = 0.041 | High (7) | › Physical activity and fruit consumption were higher in controls (p = 0.012 and p = 0.029, respectively) › Consumption of 150 g fruit lowered odds by 10% (OR = 0.90 (0.82–0.98; p = 0.028) |

| › Merle et al. 2019 [49] › Europe › Prospective cohort study of the Rotterdam Study I (RS-I) and Antioxydants, Lipides Essentiels, Nutrition et maladies Oculaires (Alienor) study populations, part of the EYE-RISK project | RS-I › 21 years (1990–2011, mean follow-up time 9.9 y) › 4446 › ≥ 55 years › M and F Alienor › 6 years (2006–2012, mean follow-up time 4.1) › 550 › ≥73 years › M and F | › RS-I: 170-item validated semiquantitative FFQ at baseline › Alienor: 40-item validated FFQ at baseline and a 24 h dietary recall › mediSCORE (0–9) › Three groups: low (0–3), medium (4–5), high (6–9) › Ophthalmologic examinations and fundus photographs › AMD graded based on the Wisconsin Age-Related System (RS-I) and the ICS (Alienor) | › Progression to advanced AMD (n = 155;RS-I = 117; Alienor = 38) with subtype analysis › mediSCORE high (RS-I n = 947; Alienor n = 143) vs. mediSCORE low (RS-I, n = 1376; Alienor, n = 171) | › Model 1: unadjusted › Model 2: age, sex, AMD grade at baseline (no or early AMD), TEI, education, BMI, smoking, multivitamin or mineral supplement use, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia | › Model 1: RS-I, HR = 0.56 (0.33–0.96) p = 0.036; Alienor, ns; Combined, HR = 0.53 (0.33–0.84) p = 0.009) › Model 2: RS-I and Alienor alone = ns Combined, HR = 0.59 (0.37–0.95) p = 0.04 › No association with nvAMD › GA → RS-I, HR = 0.41 (0.16–1.03) p = 0.046; Alienor, ns; Combined, HR = 0.42 (0.20–0.90) p = 0.04 | High (RS-I = 8; Alienor = 7) | › Association remain after adjustment for two AMD-related SNPs › No single Med diet component was associated with the incidence of advanced AMD |

| › Keenan et al. 2020 [44] › USA › Retrospective analysis of two RCTs: Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) and AREDS2 | › 13 years (median follow-up 10.2 years), enrolment AREDS 1992–1998; AREDS2 2006–2008 › 7756 (13,204 eyes) › 71 ± 6.6 years › 56.5% F | › AREDS: 90-item, validated, semiquantitative FFQ at baseline AREDS2: 131-item, validated semiquantitative FFQ at baseline › aMED score (modified), ranging from 9 to 36 in main analysis, with assessment using quartile ranks (see main text for details), and from 0 to 9 in sensitivity analyses with assessment using sex-specific medians › Population divided in tertiles: T1 = low, T2 = medium, T3 = high › Eye examinations and colour fundus photographs › AMD graded based on the Wisconsin Age-Related System | › Progression to advanced AMD (AREDS, n = 2273; AREDS2, n = 2763), with subtype analysis › T3 (AREDS, n = 1349; AREDS2, n = 1224) and T2 (AREDS, n = 1436; AREDS2, n = 1101) vs. T1 (AREDS, n = 1470; AREDS2, n = 1286) | › Treatment assignment, age, sex, smoking, TEI, BMI (for AREDS only), and correlation between eyes › In combined AREDS/AREDS2 analyses, adjustment was also made for the cohort | › Combined cohort: Advanced AMD HRs = T2: 0.87 (0.80–0.94) p = 0.001; T3: 0.78 (0.71–0.85) p < 0.0001 › Subtypes › GA HRs = T2: 0.80 (0.71–0.90) p = 0.0002; T3: 0.71 (0.63–0.80) p < 0.0001 › nvAMD HRs = T2: 0.90(0.80–1.01) p = 0.08; T3: 0.84 (0.75–0.95) p = 0.005 › Large drusen HR = 0.79 (0.68–0.93) p = 0.004 | High (8) | › Analysis of interaction between aMED and genotype: in AREDS, protective effect was present only in subject with one particular protective allele › Sensitivity analyses: results showed similar pattern but were partially attenuated › Analysis of individual components of the Med diet showed that higher fish consumption was inversely associated with AMD progression |

| › Merle et al. 2020 [50] › USA › Prospective cohort within AREDS (RCT) | › 13 years (enrolment from 1992 to 1998) › 1838 › 55–80 (at baseline) › M and F | › Validated, self-administered, 90-item, semiquantitative FFQ at baseline › aMED (0–9) › Two groups: low aMED (0–3) or medium-high aMED (4–9) › Complete eye examination and retinal stereoscopic colour images › Maximal drusen size graded in a ordinal scale as detailed in the figure legend | › Drusen size progression (n = 587), defined as an eye advancing at least two grades during the study period (from grade 0 to 2, or grade 1 to 3, or grade 2 to 4) › Medium-high aMED vs. low aMED | › Age, sex, education, smoking, BMI, AREDS treatment, multivitamin supplement use, TEI, genetic variants, and maximum drusen size category at baseline in each eye | › HR = 0.83 (0.68–0.99) p = 0.049 | High (8) | › Drusen = major hallmark of AMD |

3.3. Incidence and Prevalence of AMD and the Mediterranean Diet

3.4. Progression of AMD and Related Retinal Abnormalities and the Mediterranean Diet

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Handa, J.T. How does the macula protect itself from oxidative stress? Mol. Asp. Med. 2012, 33, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wong, W.L.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Klein, R.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, T.Y. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e106–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Resnikoff, S.; Pascolini, D.; Etya’Ale, D.; Kocur, I.; Pararajasegaram, R.; Pokharel, G.P.; Mariotti, S.P. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004, 82, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Wilkinson, C.P.; Bird, A.; Chakravarthy, U.; Chew, E.; Csaky, K.; Sadda, S.R. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, Â.; Andrade, J.P. Nutritional and Lifestyle Interventions for Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Review. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 6469138. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.; Hobby, A.; Binns, A.; Crabb, D.P. How does age-related macular degeneration affect real-world visual ability and quality of life? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.R.; Mallen, C.D.; Gouldstone, M.B.; Yarham, R.; Mansell, G. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in people with age-related macular degeneration: A systematic review of observational study data. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimarolli, V.R.; Casten, R.J.; Rovner, B.W.; Heyl, V.; Sörensen, S.; Horowitz, A. Anxiety and depression in patients with advanced macular degeneration: Current perspectives. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nolan, J.; Donovan, O.O.; Kavanagh, H.; Stack, J.; Harrison, M.; Muldoon, A.; Mellerio, J.; Beatty, S. Macular pigment and percentage of body fat. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 3940–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, S.; Nolan, J.; Kavanagh, H.; Donovan, O.O. Macular pigment optical density and its relationship with serum and dietary levels of lutein and zeaxanthin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 430, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loane, E.; McKay, G.J.; Nolan, J.M.; Beatty, S. Apolipoprotein E genotype is associated with macular pigment optical density. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 2636–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chakravarthy, U.; Augood, C.; Bentham, G.; de Jong, P.; Rahu, M.; Seland, J.; Soubrane, G.; Tomazzoli, L.; Topouzis, F.; Vingerling, J.; et al. Cigarette smoking and age-related macular degeneration in the EUREYE Study. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, R.D.; Mieler, W.F.; Miller, J.W. Age-Related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2606–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seddon, J.M.; Cote, J.; Davis, N.; Rosner, B. Progression of age-related macular degeneration: Association with body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-hip ratio. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003, 121, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McGuinness, M.B.; Le, J.; Mitchell, P.; Gopinath, B.; Cerin, E.; Saksens, N.T.; Schick, T.; Hoyng, C.B.; Guymer, R.; Finger, R.P. Physical Activity and Age-related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 180, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhead, G.K.; Grigg, J.; Chang, A.A.; McCluskey, P. Dietary modification and supplementation for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R.; Lawrenson, J.G. A review of the evidence for dietary interventions in preventing or slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2014, 34, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fleckenstein, M.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Guymer, R.H.; Chakravarthy, U.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Klaver, C.C.; Wong, W.T.; Chew, E.Y. Age-Related macular degeneration. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofagha, S.; Bhisitkul, R.B.; Boyer, D.S.; Sadda, S.R.; Zhang, K.; SEVEN-UP Study Group. Seven-Year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: A multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 2292–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, G.J.; Ying, G.-S.; Toth, C.A.; Daniel, E.; Grunwald, J.E.; Martin, D.F.; Maguire, M.G. Macular Morphology and Visual Acuity in Year Five of the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, F.G.; Sadda, S.R.; Busbee, B.; Chew, E.Y.; Mitchell, P.; Tufail, A.; Brittain, C.; Ferrara, D.; Gray, S.; Honigberg, L.; et al. Chroma and Spectri Study Investigators. Efficacy and Safety of Lampalizumab for Geographic Atrophy Due to Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Chroma and Spectri Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pallauf, K.; Giller, K.; Huebbe, P.; Rimbach, G. Nutrition and healthy ageing: Calorie restriction or polyphenol-rich “MediterrAsian” diet? Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2013, 2013, 707421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sofi, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sofi, F.; Cesari, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2008, 337, a1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.-I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerburg, O.; Siems, W.G.; Hurst, J.S.; Lewis, J.W.; Kliger, D.S.; Van Kuijk, F.J. Lutein and zeaxanthin are associated with photoreceptors in the human retina. Curr. Eye Res. 1999, 19, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, E.L.; Hammond, B.R. Nutritional influences on visual development and function. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2011, 30, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickel, W. Electrical and metabolic manifestations of receptor and higher-order neuron activity in vertebrate retina. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1972, 24, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, J.R.; Vollmer-Snarr, H.R.; Zhou, J.; Jang, Y.P.; Jockusch, S.; Itagaki, Y.; Nakanishi, K. A2E-Epoxides damage DNA in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Vitamin E and other antioxidants inhibit A2E-epoxide formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 18207–18213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handelman, G.J.; A Dratz, E.; Reay, C.C.; Van Kuijk, J.G. Carotenoids in the human macula and whole retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1988, 29, 850–855. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Agrón, E.; Sperduto, R.D.; Sangiovanni, J.P.; Kurinij, N.; Davis, M.D.; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. Long-Term effects of vitamins C and E, β-carotene, and zinc on age-related macular degeneration: AREDS report no. 35. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 1604–1611.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Research Group; Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Sangiovanni, J.P.; Danis, R.P.; Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Elman, M.J.; Antoszyk, A.N.; Ruby, A.J.; Orth, D.; et al. Secondary analyses of the effects of lutein/zeaxanthin on age-related macular degeneration progression: AREDS2 report No. 3. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014, 132, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.R.; Lawrenson, J.G. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD000254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.R.; Lawrenson, J.G. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD000253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrenson, J.G.; Evans, J.R. Omega 3 fatty acids for preventing or slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, CD010015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mares, J.A.; Voland, R.P.; Sondel, S.A.; Millen, A.E.; LaRowe, T.; Moeller, S.M.; Klein, M.L.; Blodi, B.A.; Chappell, R.J.; Tinker, L.; et al. Healthy lifestyles related to subsequent prevalence of age-related macular degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 129, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Steffen, L.M. Nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns as exposures in research: A framework for food synergy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78 (Suppl. 3), 508s–513s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Pereson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Modesti, P.A.; Reboldi, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Agyemang, C.; Remuzzi, G.; Rapi, S.; Perruolo, E.; Parati, G.; ESH Working Group on CV Risk in Low Resource Settings. Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Food groups and risk of age-related macular degeneration: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 2123–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, C.; Mancini, F.; Rajaobelina, K.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Balkau, B.; Bonnet, F.; Fagherazzi, G. Diet and risk of diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, T.D.; Agrón, E.; Mares, J.A.; Clemons, T.E.; Van Asten, F.; Swaroop, A.; Chew, E.Y.; AREDS Research Group. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Progression to Late Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the Age-Related Eye Disease Studies 1 and 2. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 1515–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, R.E.; Woodside, J.V.; McGrath, A.; Young, I.S.; Vioque, J.L.; Chakravarthy, U.; de Jong, P.T.; Rahu, M.; Seland, J.; Soubrane, G.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Score and Its Association with Age-Related Macular Degeneration: The European Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunes, S.; Alves, D.; Figueira, J.; Santos, L.; Silva, R.; Barreto, P.; Raimundo, M.; da Luz Cachulo, M.; Farinha, C.; Laíns, I.; et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and its association with age-related macular degeneration. The Coimbra Eye Study—Report 4. Nutrition 2018, 51–52, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimundo, M.; Mira, F.; Cachulo, M.D.L.; Barreto, P.; Ribeiro, L.; Farinha, C.; Laíns, I.; Nunes, S.; Alves, D.; Figueira, J.; et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet, lifestyle and age-related macular degeneration: The Coimbra Eye Study—Report 3. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018, 96, e926–e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merle, B.M.; Silver, R.E.; Rosner, B.; Seddon, J.M. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet, genetic susceptibility, and progression to advanced macular degeneration: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, B.M.J.; Colijn, J.M.; Cougnard-Grégoire, A.; de Koning-Backus, A.P.M.; Delyfer, M.N.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; Meester-Smoor, M.; Féart, C.; Verzijden, T.; Samieri, C.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Incidence of Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration: The EYE-RISK Consortium. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merle, B.M.J.; Rosner, B.; Seddon, J.M. Genetic Susceptibility, Diet Quality, and Two-Step Progression in Drusen Size. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunier, V.; Merle, B.M.J.; Delyfer, M.N.; Cougnard-Grégoire, A.; Rougier, M.B.; Amouyel, P.; Lambert, J.C.; Dartigues, J.F.; Korobelnik, J.F.; Delcourt, C. Incidence of and Risk Factors Associated with Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Four-Year Follow-up From the ALIENOR Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Kouris-Blazos, A.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Gnardellis, C.; Lagiou, P.; Polychronopoulos, E.; Vassilakou, T.; Lipworth, L.; Trichopoulos, D. Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ 1995, 311, 1457–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cachulo Mda, L.; Lobo, C.; Figueira, J.; Ribeiro, L.; Laíns, I.; Vieira, A.; Nunes, S.; Costa, M.; Simão, S.; Rodrigues, V.; et al. Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Portugal: The Coimbra Eye Study—Report 1. Ophthalmologica 2015, 233, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augood, C.A.; Vingerling, J.R.; de Jong, P.T.; Chakravarthy, U.; Seland, J.; Soubrane, G.; Tomazzoli, L.; Topouzis, F.; Bentham, G.; Rahu, M.; et al. Prevalence of Age-Related Maculopathy in Older Europeans: The European Eye Study (EUREYE). Arch. Ophthalmol. 2006, 124, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Langer, R.D.; White, E.; E Lewis, C.; Kotchen, J.M.; Hendrix, S.L.; Trevisan, M. The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study: Baseline characteristics of participants and reliability of baseline measures. Ann. Epidemiol. 2003, 13, S107–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Davis, M.D.; Magli, Y.L.; Segal, P.; Klein, B.E.; Hubbard, L. The Wisconsin age-related maculopathy grading system. Ophthalmology 1991, 98, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis, R.P.; Domalpally, A.; Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Armstrong, J.; SanGiovanni, J.P.; Ferris, F. Methods and Reproducibility of Grading Optimized Digital Color Fundus Photographs in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2 Report Number 2). Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 4548–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, R.; Klaver, C.C.; Vingerling, J.R.; Hofmanm, A.; de Jong, P.T. The risk and natural course of age-related maculopathy: Follow-Up at 6 1/2 years in the Rotterdam study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003, 121, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bird, A.; Bressler, N.; Bressler, S.; Chisholm, I.; Coscas, G.; Davis, M.; de Jong, P.; Klaver, C.; Klein, B.; Klein, R.; et al. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. The International ARM Epidemiological Study Group. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1995, 39, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fung, T.T.; McCullough, M.L.; Newby, P.K.; Manson, J.E.; Meigs, J.B.; Rifai, N.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Diet-Quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Fernández-Jarne, E.; Serrano-Martínez, M.; Wright, M.; Gomez-Gracia, E. Development of a short dietary intake questionnaire for the quantitative estimation of adherence to a cardioprotective Mediterranean diet. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 1550–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Fernández-Jarne, E.; Serrano-Martínez, M.; Marti, A.; Martinez, J.A.; Martín-Moreno, J.M. Mediterranean diet and reduction in the risk of a first acute myocardial infarction: An operational healthy dietary score. Eur. J. Nutr. 2002, 41, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gastaldello, A.; Giampieri, F.; Quiles, J.L.; Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Aparicio, S.; García Villena, E.; Tutusaus Pifarre, K.; De Giuseppe, R.; Grosso, G.; Cianciosi, D.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean-Style Eating Pattern and Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102028

Gastaldello A, Giampieri F, Quiles JL, Navarro-Hortal MD, Aparicio S, García Villena E, Tutusaus Pifarre K, De Giuseppe R, Grosso G, Cianciosi D, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean-Style Eating Pattern and Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Nutrients. 2022; 14(10):2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102028

Chicago/Turabian StyleGastaldello, Annalisa, Francesca Giampieri, José L. Quiles, María D. Navarro-Hortal, Silvia Aparicio, Eduardo García Villena, Kilian Tutusaus Pifarre, Rachele De Giuseppe, Giuseppe Grosso, Danila Cianciosi, and et al. 2022. "Adherence to the Mediterranean-Style Eating Pattern and Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies" Nutrients 14, no. 10: 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102028

APA StyleGastaldello, A., Giampieri, F., Quiles, J. L., Navarro-Hortal, M. D., Aparicio, S., García Villena, E., Tutusaus Pifarre, K., De Giuseppe, R., Grosso, G., Cianciosi, D., Forbes-Hernández, T. Y., Nabavi, S. M., & Battino, M. (2022). Adherence to the Mediterranean-Style Eating Pattern and Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Nutrients, 14(10), 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102028