The Impact of the Different Stages of COVID-19, Time of the Week and Exercise Frequency on Mental Distress in Men and Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Set

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3. Physical Exercise Assessment

2.4. Timeframes Assessed

2.5. Categorization of Exercise Frequency

2.6. Ordinal Logistic Regression

2.7. Margins or Predicted Probabilities

3. Results

3.1. Regression Analysis Results: Physical Exercise Frequency and Mental Distress among Men and Women

3.2. Predictive Probabilities

3.2.1. Probability of Being in the Moderate Mental Distress Category for Men

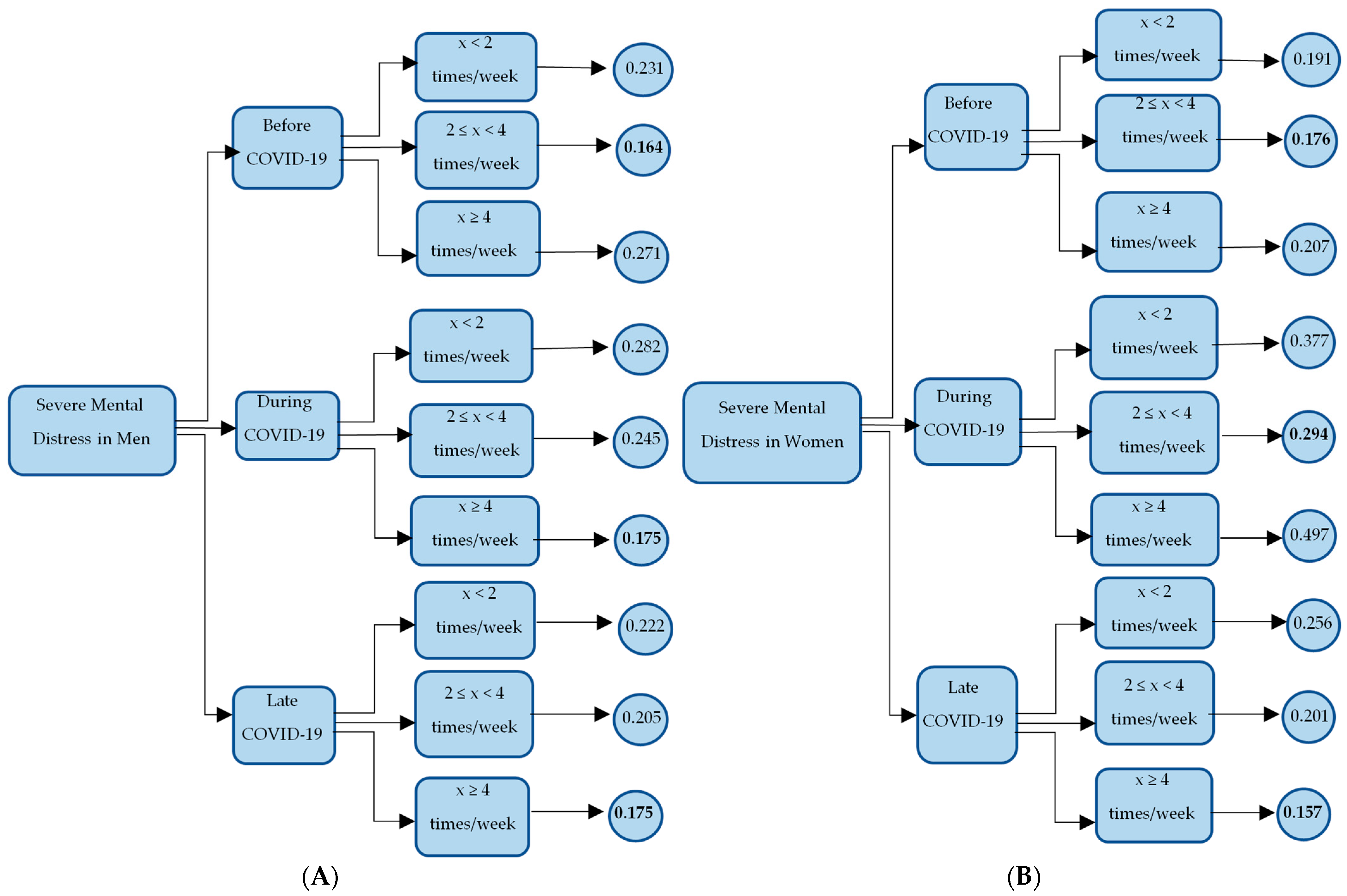

3.2.2. Probability of Being in the Severe Mental Distress Category for Men

3.2.3. Probability of Being in the Moderate Mental Distress Category for Women

3.2.4. Probability of Being in the Severe Mental Distress Category for Women

3.3. The Impact of Exercise and Time of the Week

Regression Results

3.4. Predictive Probabilities

3.4.1. During Weekdays

3.4.2. During Weekends

3.5. The Impact of Physical Exercise Frequency and Time of the Week with Respect to Gender

3.5.1. Regression Results

Men during Weekends

Men during Weekdays

Women during Weekends

Women during Weekdays

3.5.2. Predictive Probabilities

Men during Weekends

Men during Weekdays

Women during Weekends

Women during Weekdays

4. Discussion

4.1. The Modulatory Effect of COVID-19 on Physical Exercise Frequency and Mental Distress

4.2. Predictive Models for Future Pandemics

4.3. Reason for Physical Exercise

5. Conclusions and Future Direction

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Current Systematic Reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.R.; McDowell, C.P.; Lyons, M.; Herring, M.P. Resistance Exercise Training for Anxiety and Worry Symptoms among Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring, M.P.; Monroe, D.C.; Gordon, B.R.; Hallgren, M.; Campbell, M.J. Acute Exercise Effects among Young Adults with Analogue Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlard, P.A.; Cotman, C.W. Voluntary Exercise Protects against Stress-Induced Decreases in Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Protein Expression. Neuroscience 2004, 124, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uysal, N.; Kiray, M.; Sisman, A.; Camsari, U.; Gencoglu, C.; Baykara, B.; Cetinkaya, C.; Aksu, I. Effects of Voluntary and Involuntary Exercise on Cognitive Functions, and VEGF and BDNF Levels in Adolescent Rats. Biotech. Histochem. 2014, 90, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begdache, L.; Patrissy, C.M. Customization of Diet May Promote Exercise and Improve Mental Wellbeing in Mature Adults: The Role of Exercise as a Mediator. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourre, J.M. Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Psychiatry: Mood, Behaviour, Stress, Depression, Dementia and Aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2005, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McKay, J.A.; Mathers, J.C. Diet Induced Epigenetic Changes and Their Implications for Health. Acta Physiol. 2011, 202, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Lee, Y. Projected Increases in Suicide in Canada as a Consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in the General Population: A Systematic Review. J. Affect Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoro, M.; Wakimoto, K.; Otaki, N.; Fukuo, K. Increased Prevalence of Breakfast Skipping in Female College Students in COVID-19. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2021, 33, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, W.; Ashkanani, F. Does COVID-19 Change Dietary Habits and Lifestyle Behaviours in Kuwait: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begdache, L.; Sadeghzadeh, S.; Derose, G.; Abrams, C. Diet, Exercise, Lifestyle, and Mental Distress among Young and Mature Men and Women: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Lee, T.H.; Park, E.-C.; Ju, Y.J.; Han, E.; Kim, T.H. Breakfast Consumption and Depressive Mood: A Focus on Socioeconomic Status. Appetite 2017, 114, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begdache, L.; Chaar, M.; Sabounchi, N.; Kianmehr, H. Assessment of Dietary Factors, Dietary Practices and Exercise on Mental Distress in Young Adults versus Matured Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifune, H.; Tajiri, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Kawahara, Y.; Hara, K.; Sato, T.; Nishi, Y.; Nishi, A.; Mitsuzono, R.; Kakuma, T.; et al. Voluntary Exercise Is Motivated by Ghrelin, Possibly Related to the Central Reward Circuit. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 244, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, M.; Guseva, E.; Perrone, M.A.; Müller, A.; Rizzo, G.; Storz, M.A. Changes in Eating Habits and Physical Activity after COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdowns in Italy. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Z.; Yip, S.P.; Li, L.; Zheng, X.-X.; Tong, K.-Y. The Effects of Voluntary, Involuntary, and Forced Exercises on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Motor Function Recovery: A Rat Brain Ischemia Model. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Albert, P.R. Why Is Depression More Prevalent in Women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, L. Fundamental Sex Difference in Human Brain Architecture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffy, J.F.; Cain, S.W.; Chang, A.-M.; Phillips, A.J.K.; Münch, M.Y.; Gronfier, C.; Wyatt, J.K.; Dijk, D.-J.; Wright, K.P., Jr.; Czeisler, C.A. Sex Difference in the Near-24-Hour Intrinsic Period of the Human Circadian Timing System. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108 (Suppl. S3), 15602–15608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ingalhalikar, M.; Smith, A.; Parker, D.; Satterthwaite, T.D.; Elliott, M.A.; Ruparel, K.; Hakonarson, H.; Gur, R.E.; Gur, R.C.; Verma, R. Sex Differences in the Structural Connectome of the Human Brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The CBHSQ Data Review: Psychological Distress and Mortality among Adults in the U.S. General Population. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/CBHSQ-DR-C11-MI-Mortality-2014/CBHSQ-DR-C11-MI-Mortality-2014.htm (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Faulkner, J.; O’Brien, W.J.; McGrane, B.; Wadsworth, D.; Batten, J.; Askew, C.D.; Badenhorst, C.; Byrd, E.; Coulter, M.; Draper, N.; et al. Physical Activity, Mental Health and Wellbeing of Adults during Initial COVID-19 Containment Strategies: A Multi-Country Cross-Sectional Analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giustino, V.; Parroco, A.M.; Gennaro, A.; Musumeci, G.; Palma, A.; Battaglia, G. Physical Activity Levels and Related Energy Expenditure during COVID-19 Quarantine among the Sicilian Active Population: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, C.P.; Lesser, I.A. The Impact of COVID-19 on Women’s Physical Activity Behavior and Mental Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chekroud, S.R.; Gueorguieva, R.; Zheutlin, A.B.; Paulus, M.; Krumholz, H.M.; Krystal, J.H.; Chekroud, A.M. Association between Physical Exercise and Mental Health in 1·2 Million Individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begdache, L.; Kianmehr, H.; Najjar, H.; Witt, D.; Sabounchi, N.S. A Differential Threshold of Breakfast, Caffeine and Food Groups May Be Impacting Mental Wellbeing in Young Adults: The Mediation Effect of Exercise. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 676604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibaut, F.; van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P.J.M. Women’s Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2020, 1, 588372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Impacts of Working From Home During COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Wellbeing of Office Workstation Users. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Singh, T.; Arya, Y.K.; Mittal, S. Physical Fitness and Exercise During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Enquiry. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caretto, A.; Pintus, S.; Petroni, M.L.; Osella, A.R.; Bonfiglio, C.; Morabito, S.; Zuliani, P.; Sturda, A.; Castronuovo, M.; Lagattolla, V.; et al. Determinants of Weight, Psychological Status, Food Contemplation and Lifestyle Changes in Patients with Obesity during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Nationwide Survey Using Multiple Correspondence Analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, W.; Desalegn, H.; Solomon, S. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown on Weight Status and Factors Associated with Weight Gain among Adults in Massachusetts. Clin. Obes. 2021, 11, e12453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Balhara, Y.P.S.; Gupta, C.S. Gender Differences in Stress Response: Role of Developmental and Biological Determinants. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2011, 20, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pariante, C.M.; Lightman, S.L. The HPA Axis in Major Depression: Classical Theories and New Developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, C.; Lv, C.; Zhu, J. Association between Physical Exercise and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Outbreak in China: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 722448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovdii, M.A.; Solomakha, K.M.; Yasynetskyi, M.O.; Ponomarenko, N.P.; Rydzel, Y.M. A study of physical activity levels and quality of life in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Wiad. Lek. 2021, 74, 1405–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, B.B.; Carroll, H.A.; Lustyk, M.K.B. Gender Differences in Exercise Habits and Quality of Life Reports: Assessing the Moderating Effects of Reasons for Exercise. Int. J. Lib. Arts Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lustyk, M.K.B.; Widman, L.; Paschane, A.A.E.; Olson, K.C. Physical Activity and Quality of Life: Assessing the Influence of Activity Frequency, Intensity, Volume, and Motives. Behav. Med. 2004, 30, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Percentage | Number of Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Males | 31.54% | 732 |

| Females | 68.46% | 1589 |

| Age (Years) | ||

| Under 18 | 0.95% | 22 |

| 18–29 | 91.68% | 2128 |

| 30–39 | 2.41% | 56 |

| 40–49 | 1.46% | 34 |

| above 50 | 3.50% | 81 |

| Region | ||

| North America | 97.37% | 2260 |

| Europe | 1.21% | 28 |

| MENA | 0.26% | 6 |

| Asia | 0.34% | 8 |

| South America | 0.22% | 5 |

| Australia | 0.34% | 8 |

| Africa | 0.26% | 6 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 1.08% | 25 |

| High school | 53.34% | 1238 |

| College | 40.42% | 938 |

| Masters | 4.09% | 95 |

| Doctoral | 1.07% | 25 |

| COVID-19 Era | Exercise Frequency | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > |z| | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | Baseline | |||||

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.430 | 0.455 | −0.950 | 0.344 | −1.323 | 0.462 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.080 | 0.517 | −0.150 | 0.878 | −1.093 | 0.934 | |

| During COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 0.311 | 0.373 | 0.830 | 0.405 | −0.421 | 1.042 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.106 | 0.369 | 0.290 | 0.774 | −0.617 | 0.829 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.224 | 0.379 | −0.590 | 0.555 | −0.968 | 0.519 | |

| Late COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | −0.026 | 0.457 | −0.060 | 0.954 | −0.923 | 0.870 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.195 | 0.456 | −0.430 | 0.669 | −1.088 | 0.698 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.350 | 0.446 | −0.790 | 0.432 | −1.225 | 0.524 | |

| COVID-19 Era | Exercise Frequency | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > |z| | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | Baseline | |||||

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.104 | 0.187 | −0.560 | 0.578 | −0.471 | 0.263 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 0.121 | 0.268 | 0.450 | 0.653 | −0.405 | 0.646 | |

| During COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 1.022 | 0.161 | 6.370 | 0.000 | 0.708 | 1.337 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.609 | 0.170 | 3.580 | 0.000 | 0.276 | 0.943 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 1.586 | 0.269 | 5.900 | 0.000 | 1.059 | 2.114 | |

| Late COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 0.430 | 0.220 | 1.960 | 0.050 | −0.001 | 0.860 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.053 | 0.236 | 0.230 | 0.822 | −0.409 | 0.515 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.227 | 0.415 | −0.550 | 0.584 | −1.040 | 0.585 | |

| Lowest Probability of Severe MD | Highest Probability of Severe MD | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Before COVID-19 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | High |

| During COVID-19 | High | Moderate | Low | High |

| Late COVID-19 | High | High | Low | Low |

| Lowest Probability of Moderate MD | Highest Probability of Moderate MD | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Before COVID-19 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | High |

| During COVID-19 | High | High | Low | Moderate |

| Late COVID-19 | High | High | Low | Low |

| COVID-19 Era | Exercise Frequency | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > |z| | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | Baseline | |||||

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.350 | 0.201 | −1.750 | 0.081 | −0.744 | 0.043 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 0.073 | 0.271 | 0.270 | 0.788 | −0.457 | 0.603 | |

| During COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 0.787 | 0.167 | 4.720 | 0.000 | 0.460 | 1.114 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.449 | 0.169 | 2.650 | 0.008 | 0.117 | 0.781 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 0.334 | 0.203 | 1.650 | 0.099 | −0.063 | 0.732 | |

| Late COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 0.428 | 0.211 | 2.030 | 0.043 | 0.014 | 0.842 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.012 | 0.218 | −0.050 | 0.956 | −0.439 | 0.415 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.275 | 0.272 | −1.010 | 0.312 | −0.808 | 0.258 | |

| COVID-19 Era | Exercise Frequency | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > |z| | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | Baseline | |||||

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.473 | 0.342 | 1.380 | 0.166 | −0.197 | 1.143 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 0.329 | 0.483 | 0.680 | 0.495 | −0.617 | 1.275 | |

| During COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 1.145 | 0.300 | 3.810 | 0.000 | 0.557 | 1.734 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.406 | 0.354 | 1.150 | 0.251 | −0.287 | 1.099 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 0.394 | 0.473 | 0.830 | 0.406 | −0.534 | 1.322 | |

| Late COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | −0.092 | 0.573 | −0.160 | 0.873 | −1.214 | 1.031 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.456 | 0.806 | −0.570 | 0.572 | −2.035 | 1.124 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −2.581 | 2.248 | −1.150 | 0.251 | −6.987 | 1.824 | |

| Lowest Probability | Highest Probability | |

| Moderate MD | Moderate MD | |

| Before COVID-19 | Moderate | High |

| During COVID-19 | High | Low |

| Late COVID-19 | High | Low |

| Lowest Probability | Highest Probability | |

| Severe MD | Severe MD | |

| Before COVID-19 | Moderate | High |

| During COVID-19 | High | Low |

| Late COVID-19 | High | Low |

| Lowest Probability | Highest Probability | |

| Moderate MD | Moderate MD | |

| Before COVID-19 | High | Moderate |

| During COVID-19 | Moderate- High | Low |

| Late COVID-19 | High | Low |

| Lowest Probability | Highest Probability | |

| Severe MD | Severe MD | |

| Before COVID-19 | High | Moderate |

| During COVID-19 | High | Low |

| Late COVID-19 | High | Low |

| COVID-19 Era | Exercise Frequency | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > |z| | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | Baseline | |||||

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 2.522 | 1.132 | 2.230 | 0.026 | 0.304 | 4.741 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 3.305 | 1.295 | 2.550 | 0.011 | 0.766 | 5.844 | |

| During COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 2.806 | 0.898 | 3.120 | 0.002 | 1.045 | 4.566 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 1.875 | 0.979 | 1.920 | 0.055 | −0.043 | 3.794 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 2.131 | 0.994 | 2.140 | 0.032 | 0.184 | 4.079 | |

| Late COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 1.441 | 1.449 | 0.990 | 0.320 | −1.398 | 4.280 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 1.367 | 1.570 | 0.870 | 0.384 | −1.710 | 4.444 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −1.493 | 3.001 | −0.500 | 0.619 | −7.376 | 4.389 | |

| COVID-19 Era | Physical Exercise Frequency | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > |z| | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | Baseline | |||||

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −1.179 | 0.534 | −2.210 | 0.027 | −2.225 | −0.133 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.799 | 0.599 | −1.330 | 0.183 | −1.974 | 0.376 | |

| During COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | −0.450 | 0.439 | −1.020 | 0.306 | −1.310 | 0.411 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.358 | 0.430 | −0.830 | 0.404 | −1.201 | 0.484 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.732 | 0.444 | −1.650 | 0.099 | −1.603 | 0.138 | |

| Late COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | −0.619 | 0.519 | −1.190 | 0.232 | −1.636 | 0.397 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.645 | 0.512 | −1.260 | 0.207 | −1.648 | 0.358 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.864 | 0.498 | −1.730 | 0.083 | −1.839 | 0.112 | |

| COVID-19 Era | Exercise Frequency | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > |z| | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | Baseline | |||||

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.267 | 0.376 | 0.710 | 0.477 | −0.469 | 1.004 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.176 | 0.546 | −0.320 | 0.747 | −1.246 | 0.895 | |

| During COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | 0.781 | 0.344 | 2.270 | 0.023 | 0.107 | 1.455 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.315 | 0.420 | 0.750 | 0.454 | −0.509 | 1.139 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 16.612 | 804.827 | 0.020 | 0.984 | −1560.819 | 1594.043 | |

| Late COVID-19 | x < 2 times per week | −0.466 | 0.710 | −0.660 | 0.512 | −1.858 | 0.926 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.842 | 1.186 | −0.710 | 0.478 | −3.167 | 1.483 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 0 Empty | ||||||

| COVID-19 Era | Exercise Frequency | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p > |z| | [95% Confidence Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID | x < 2 times per week | Baseline | |||||

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | −0.153 | 0.222 | −0.690 | 0.490 | −0.587 | 0.281 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 0.285 | 0.317 | 0.900 | 0.369 | −0.336 | 0.905 | |

| During COVID | x < 2 times per week | 1.147 | 0.187 | 6.140 | 0.000 | 0.781 | 1.513 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.776 | 0.195 | 3.980 | 0.000 | 0.394 | 1.158 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | 1.566 | 0.285 | 5.500 | 0.000 | 1.008 | 2.124 | |

| Late COVID | x < 2 times per week | 0.688 | 0.241 | 2.860 | 0.004 | 0.216 | 1.159 |

| 2 ≤ x < 4 times per week | 0.171 | 0.252 | 0.680 | 0.496 | −0.322 | 0.664 | |

| x ≥ 4 times per week | −0.142 | 0.424 | −0.330 | 0.738 | −0.973 | 0.689 | |

| Lowest Probability of Moderate MD | Highest Probability of Moderate MD | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Before COVID-19 | Low | High | High | Moderate |

| During COVID-19 | High | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Late COVID-19 | High | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Lowest Probability of Severe MD | Highest Probability of Severe MD | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Before COVID-19 | Low | High | High | Moderate |

| During COVID-19 | High | Moderate | Low | High |

| Late COVID-19 | High | Low | Moderate | High |

| Lowest Probability of Moderate MD | Highest Probability of Moderate MD | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Before COVID-19 | Moderate | High | Low | High |

| During COVID-19 | High | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Late COVID-19 | High | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Lowest Probability of Severe MD | Highest Probability of Severe MD | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Before COVID-19 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| During COVID-19 | High | High | Moderate | High |

| Late COVID-19 | High | High | Low | Low |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Begdache, L.; Danesharasteh, A.; Ertem, Z. The Impact of the Different Stages of COVID-19, Time of the Week and Exercise Frequency on Mental Distress in Men and Women. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132572

Begdache L, Danesharasteh A, Ertem Z. The Impact of the Different Stages of COVID-19, Time of the Week and Exercise Frequency on Mental Distress in Men and Women. Nutrients. 2022; 14(13):2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132572

Chicago/Turabian StyleBegdache, Lina, Anseh Danesharasteh, and Zeynep Ertem. 2022. "The Impact of the Different Stages of COVID-19, Time of the Week and Exercise Frequency on Mental Distress in Men and Women" Nutrients 14, no. 13: 2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132572

APA StyleBegdache, L., Danesharasteh, A., & Ertem, Z. (2022). The Impact of the Different Stages of COVID-19, Time of the Week and Exercise Frequency on Mental Distress in Men and Women. Nutrients, 14(13), 2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132572