The Impact of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics during Pregnancy or Lactation on the Intestinal Microbiota of Children Born by Cesarean Section: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

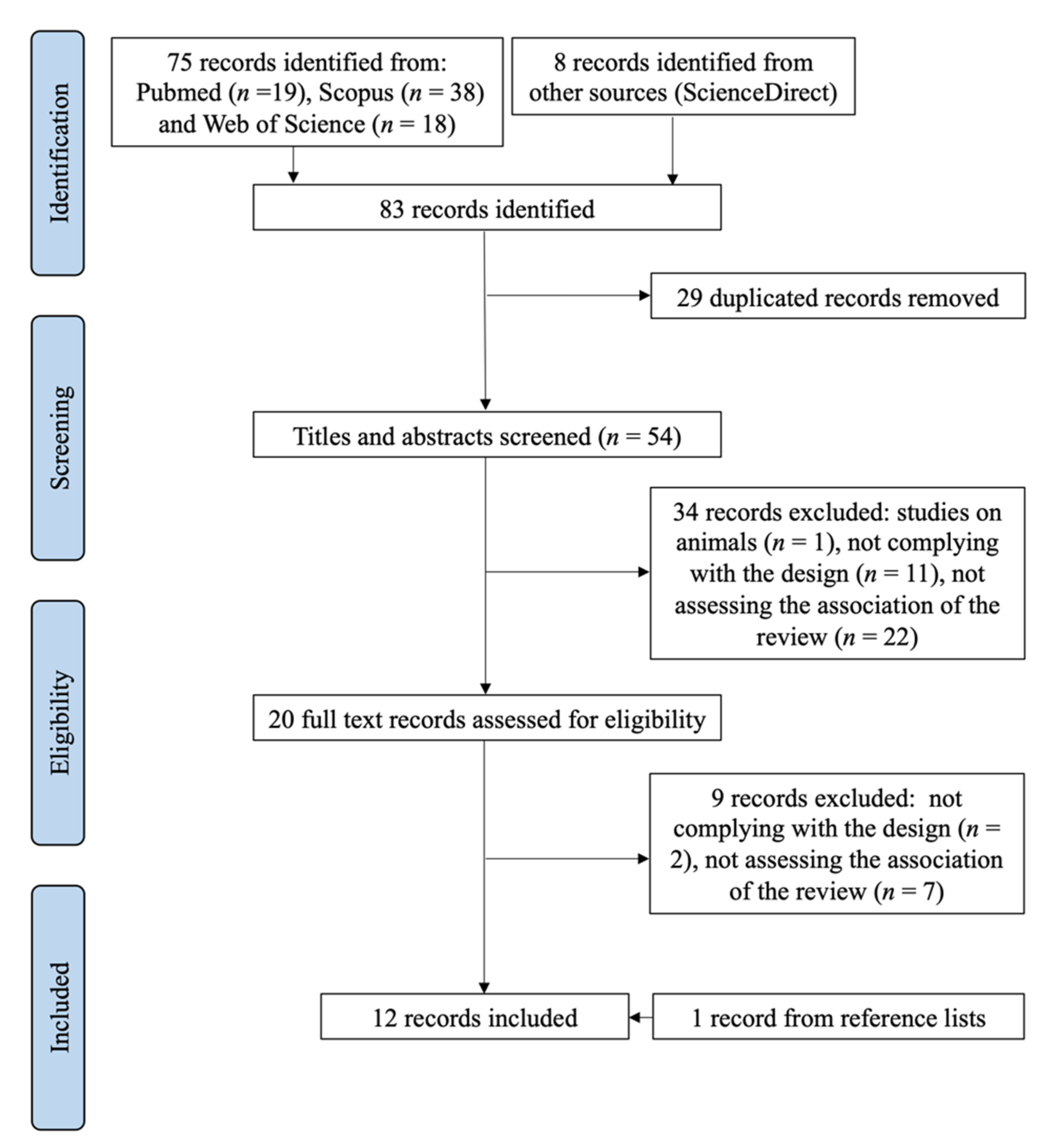

3.1. Selection Process

3.2. Characteristics of Studies Selected

3.3. Interventions with Probiotics

3.4. Interventions with Prebiotics

3.5. Interventions with Synbiotics

3.6. Stool Sample Collection and Microbial Analysis Methods

3.7. Study Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hooper, L.V.; Macpherson, A.J. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautava, S. Early microbial contact, the breast milk microbiome and child health. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2016, 7, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Alam, D.; Danopoulos, S.; Grubbs, B.; Ali, N.; MacAogain, M.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Warburton, D.; Gaggar, A.; Ambalavanan, N.; Lal, C.V. Human Fetal Lungs Harbor a Microbiome Signature. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sola-Leyva, A.; Andrés-León, E.; Molina, N.M.; Terron-Camero, L.C.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Sáez-Lara, M.J.; Gonzalvo, M.C.; Sánchez, R.; Ruíz, S.; Martínez, L.; et al. Mapping the entire functionally active endometrial microbiota. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, J. Developmental aspects of maternal-fetal, and infant gut microbiota and implications for long-term health. Matern Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 2015, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhuang, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhuang, J.; Li, Q.; Feng, Z. Intestinal microbiota in early life and its implications on childhood health. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2019, 17, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhare, S.V.; Patangia, D.V.V.; Patil, R.H.; Shouche, Y.S.; Patil, N.P. Factors influencing the gut microbiome in children: From infancy to childhood. J. Biosci. 2019, 44, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutayisire, E.; Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Tao, F. The mode of delivery affects the diversity and colonization pattern of the gut microbiota during the first year of infants’ life: A systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. Factors influencing the intestinal microbiome during the first year of life. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, e315–e335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasucci, G.; Rubini, M.; Riboni, S.; Morelli, L.; Bessi, E.; Retetangos, C. Mode of delivery affects the bacterial community in the newborn gut. Early Hum. Dev. 2010, 86, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, K.; Zhang, C.; Tian, J. The effects of different modes of delivery on the structure and predicted function of intestinal microbiota in neonates and early infants. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirilun, S.; Takahashi, H.; Boonyaritichaikij, S.; Chaiyasut, C.; Lertruangpanya, P.; Koga, Y.; Mikami, K. Impact of maternal bifidobacteria and the mode of delivery on Bifidobacterium microbiota in infants. Benef. Microbes 2015, 6, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.B.; Konya, T.; Maughan, H.; Guttman, D.S.; Field, C.J.; Chari, R.S.; Sears, M.R.; Becker, A.B.; Scott, J.A.; Kozyrskyj, A.L. Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: Profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months. Cmaj 2013, 185, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Costello, E.K.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stinson, L.F.; Payne, M.S.; Keelan, J.A. A critical review of the bacterial baptism hypothesis and the impact of cesarean delivery on the infant microbiome. Front Med. 2018, 5, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, J.T.A.; DeFranco, E. The influence of mode of delivery on breastfeeding initiation in women with a prior cesarean delivery: A population-based study. Breastfeed. Med. 2013, 8, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rowe-Murray, H.J.; Fisher, J.R. Baby friendly hospital practices: Cesarean section is a persistent barrier to early initiation of breastfeeding. Birth 2002, 29, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M.K.; McGuire, M.A. Human milk: Mother nature’s prototypical probiotic food? Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, L.; Langa, S.; Martín, V.; Maldonado, A.; Jiménez, E.; Martín, R.; Rodríguez, J.M. The human milk microbiota: Origin and potential roles in health and disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 69, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.A.; Iyengar, R.S. Breast milk, microbiota, and intestinal immune homeostasis. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 77, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swanson, K.S.; Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Reimer, R.A.; Reid, G.; Verbeke, K.; Scott, K.P.; Holscher, H.D.; Azad, M.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Calatayud, G.; Suárez, E.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Pérez-Moreno, J. Microbiota in women; clinical applications of probiotics. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuniati, T.S.A. Atopic occurence on six-month-old infants between probiotic formula-fed and non probiotic formula-fed healthy born by cesarean delivery. Maj. Kedokt. Med. J. 2011, 43, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mastromarino, P.; Capobianco, D.; Miccheli, A.; Praticò, G.; Campagna, G.; Laforgia, N.; Capursi, T.; Baldassarre, M.E. Administration of a multistrain probiotic product (VSL#3) to women in the perinatal period differentially affects breast milk beneficial microbiota in relation to mode of delivery. Pharmacol Res. 2015, 95–96, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Baglatzi, L.; Gavrili, S.; Stamouli, K.; Zachaki, S.; Favre, L.; Pecquet, S.; Benyacoub, J.; Costalos, C. Effect of Infant Formula Containing a Low Dose of the Probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis CNCM I-3446 on Immune and Gut Functions in C-Section Delivered Babies: A Pilot Study. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2016, 10, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooper, P.; Bolton, K.D.; Velaphi, S.; de Groot, N.; Emady-Azar, S.; Pecquet, S.; Steenhout, P. Early benefits of a starter formula enriched in prebiotics and probiotics on the gut microbiota of healthy infants born to HIV+ mothers: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2016, 10, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia Rodenas, C.L.; Lepage, M.; Ngom-Bru, C.; Fotiou, A.; Papagaroufalis, K.; Berger, B. Effect of Formula Containing Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 on Fecal Microbiota of Infants Born by Cesarean-Section. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 63, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazanella, M.; Maier, T.V.; Clavel, T.; Lagkouvardos, I.; Lucio, M.; Maldonado-Gòmez, M.X.; Autran, C.; Walter, J.; Bode, L.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; et al. Randomized controlled trial on the impact of early-life intervention with bifidobacteria on the healthy infant fecal microbiota and metabolome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1274–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chua, M.C.; Ben-Amor, K.; Lay, C.; Neo, A.G.E.; Chiang, W.C.; Rao, R.; Chew, C.; Chaithongwongwatthana, S.; Khemapech, N.; Knol, J.; et al. Effect of synbiotic on the gut microbiota of cesarean delivered infants: A randomized, double-blind, multicenter study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, S.A.; Hutton, A.A.; Contreras, L.N.; Shaw, C.A.; Palumbo, M.C.; Casaburi, G.; Xu, G.; Davis, J.C.C.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Henrick, B.M.; et al. Persistence of Supplemented Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis EVC001 in Breastfed Infants. mSphere 2017, 2, e00501-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korpela, K.; Salonen, A.; Vepsäläinen, O.; Suomalainen, M.; Kolmeder, C.; Varjosalo, M.; Miettinen, S.; Kukkonen, K.; Savilahti, E.; Kuitunen, M.; et al. Probiotic supplementation restores normal microbiota composition and function in antibiotic-treated and in caesarean-born infants. Microbiome 2018, 6, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hurkala, J.; Lauterbach, R.; Radziszewska, R.; Strus, M.; Heczko, P. Effect of a short-time probiotic supplementation on the abundance of the main constituents of the gut microbiota of term newborns delivered by cesarean section—A randomized, prospective, controlled clinical trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estorninos, E.; Lawenko, R.B.; Palestroque, E.; Sprenger, N.; Benyacoub, J.; Kortman, G.A.M.; Boekhorst, J.; Bettler, J.; Cercamondi, C.I.; Berger, B. Term infant formula supplemented with milk-derived oligosaccharides shifts the gut microbiota closer to that of human milk-fed infants and improves intestinal immune defense: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 115, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phavichitr, N.; Wang, S.; Chomto, S.; Tantibhaedhyangkul, R.; Kakourou, A.; Intarakhao, S.; Jongpiputvanich, S.; Roeselers, G.; Knol, J. Impact of synbiotics on gut microbiota during early life: A randomized, double-blind study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarman, M.; Knol, J. Quantitative real-time PCR assays to identify and quantify fecal Bifidobacterium species in infants receiving a prebiotic infant formula. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 2318–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chichlowski, M.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Mills, D.A. The influence of milk oligosaccharides on microbiota of infants: Opportunities for formulas. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huurre, A.; Kalliomäki, M.; Rautava, S.; Rinne, M.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Mode of delivery—Effects on gut microbiota and humoral immunity. Neonatology 2008, 93, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundell, A.C.; Björnsson, V.; Ljung, A.; Ceder, M.; Johansen, S.; Lindhagen, G.; Törnhage, C.J.; Adlerberth, I.; Wold, A.E.; Rudin, A. Infant B cell memory differentiation and early gut bacterial colonization. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 4315–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simeoni, U.; Berger, B.; Junick, J.; Blaut, M.; Pecquet, S.; Rezzonico, E.; Grathwohl, D.; Sprenger, N.; Brüssow, H.; Szajewska, H.; et al. Gut microbiota analysis reveals a marked shift to bifidobacteria by a starter infant formula containing a synbiotic of bovine milk-derived oligosaccharides and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. Lactis CNCM I-3446. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 2185–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author/Year | Design | Population | Intervention | Control | Intervention Duration | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuniati, 2013 [28] | CT | n = 122 newborns n (IG) = 87 (50% CD) n (CG) = 81 (50% CD) | Mixed feeding plus B. lactis DSM 10140 | Mixed feeding | From birth to 2 months | Increase of B. lactis in stool of IG compared to CG. In the intervention group, B. lactis was found in the 80% of the CD and in the 38% of the VD infants. Higher counts of Bifidobacteria in CD infants belonging to the IG compared to those in the CG at 1 month |

| Mastromarino, 2015 [29] | RCT-DB | n = 66 pairs pregnant female-newborns n (IG) = 33 (42.4% CD) n (CG) = 33 (31.3% CD) | Oral daily ingestion of 9 × 1011 of VSL# probiotic mixture: Lactobacillus acidophilus DSM 24735, L. plantarum DSM 24730, L. paracasei DSM 24733, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus DSM 24734, Bifidobacterium longum DSM 24736, B. breve DSM 24732, B. infantis DSM 24737, and Streptococcus thermophilus DSM 24731 | Corn starch | From 36th week of pregnancy to 4 weeks after delivery | Beneficial gut microbiota instauration, especially in CD newborns. Significantly higher amounts of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in colostrum and mature milk of probiotic treated women delivering vaginally, compared to CG |

| Baglatzi, 2016 [30] | RCT-DB | n = 198 CD newborns n (IG1) = 77 n (IG2) = 77 n (CG) = 44 | Infant formula plus: IG1: 107 CFU/g B. lactis CNCM I-3446 IG2: 104 CFU/g B. lactis CNCM I-3446 | Breastfeeding (min. 4 months) | From birth to 6 months of age | At 4 months, no differences were found regarding total bifidobacteria. In 85% of IG1 and 47% of IG2 feces, B. lactis was detected |

| Cooper, 2016 [31] | RCT-DB | n = 421 newborns n (IG) = 207 (44% CD) n (CG) = 214 (47% CD) | Infant formula plus 1 × 107 CFU/g of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis CNCM I-3446 and 5.8 g/100 g of a mixture of bovine milk-derived oligosaccharides (BMOS) | Infant formula | From birth to 6 months of age | Infant formula supplemented with the synbiotic induced a bifidogenic effect in both delivering modes, but more explicitly correcting the low bifidobacterial level found in CD infants. Lowered fecal pH and improved fecal microbiota independently of the delivery mode |

| García-Ródenas, 2016 [32] | RCT-DB | n = 40 newborns n (IG) = 20 (50% CD) n (CG) = 20 (50% CD) | Infant formula plus 1.2 × 109 CFU/L of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 | Infant formula | From 72 hours after delivery until 6 months of age | Increase in L. reuteri in infants receiving the probiotic formula, independent of the delivery mode and age. L reuteri promoted the growth of other Lactobacillus spp. and strongly modulated the microbiota in CD babies |

| Bazanella, 2017 [33] | RCT-DB | n = 106 newborns n (IG) = 48 (42% CD) n (CG) = 49 (45% CD) n (RG) = 9 breastfed | Infant formula plus 107 CFU/g of a mixture of Bifidobacterium bifidum BF3, B. breve BR3, B. longum BG7, B. longum subspecies infantis BT1 | Infant formula | From delivery until 1 year of age | IG infants showed decreased occurrence of Bacteroides and Blautia spp. at month 1. No detectable long-term effects for gut microbiota assembly or function |

| Chien Chua, 2017 [34] | RCT-DB | n = 183 newborns n (IG1) = 52 CD n (IG2) = 51 CD n (CG) = 80 (38% CD) | Infant formula plus: IG1: 0.8 g/100 mL scGOS/Lcfos. IG2: 0.8 g/100 mL scGOS/Lcfos + B. breve M-16V (7.5 × 108 CFU/100 mL) | Infant formula | From birth (1–3 days at the latest) until 16 weeks of age | Supplementation with both prebiotics (IG1) and synbiotics (IG2) in CD infants allows fast colonization from the first days of life, emulating the gut physiological conditions observed in vaginally delivered infants |

| Frese, 2017 [35] | RCT | n = 66 newborns n (IG) = 34 (32% CD) n (CG) = 32 (28% CD) | Breastfeeding plus a daily capsule containing 1.8 × 1010 CFU of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis EVC001 | Breastfeeding | From day 7 to day 28 of life | Increase in Bifidobacteriaceae, in particular B. infantis, in IG, persisting more than 30 days after probiotic supplementation ceased. Relative abundances of Enterobacteriaceae, Clostridiaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Pasteurellaceae, Micrococcaceae, and Lachnospiraceae diminished in IG compared to CG |

| Korpela, 2018 [36] | RCT-DB | n = 422 pairs pregnant female-newborns n (IG) = 199 (18% CD) n (CG) = 223 (20% CD) | Mothers: probiotic mixture containing 5 × 109 CFU Lactobacillus GG (ATCC 53103), 5 × 109 CFU L. rhamnosus LC705, 2 × 108 CFU Bifidobacterium breve Bb99, and 2 × 109 CFU Propionibacterium freudenreichii ssp. shermanii JS, twice a dayNewborns: same probiotic mixture as mothers, mixed with 0.8 g of GOS | Microcrystalline cellulose | Mothers: last month of pregnancy.Infants: from birth until 6 months of age | Daily B. breve and L. rhamnosus supplementation combined with breastfeeding is a safe and effective method to support the microbiota in CD and in antibiotic-treated infants |

| Hurkala, 2020 [37] | RCT | n = 148 C-section newborns n (IG) = 71 n (CG) = 77 | Oral capsule containing 2 × 106 CFU/day Bifidobacterium breve PB04 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus KL53A | Mother’s milk or formula | From delivery to 6 days of life | Supplementation of CD neonates with a mixture of L. rhamnosus and B. breve strains immediately after birth increases numbers of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in their gut |

| Estorninos, 2021 [38] | RCT-DB | n = 226 newborns n (IG) = 114 (17% CD) n (CG) = 112 (18% CD) n (RG) = 70 breastfed (19% CD) | Infant formula containing 7.2 g/L bovine milk-derived oligosaccharides (MOS) | Infant formula | From 21–26 days of age until 6 months of life | Supplementation with MOS shifts the gut microbiota composition of CD infants towards that of vaginally delivered, breastfed infants |

| Phavichitr, 2021 [39] | RCT-DB | n = 290 C-section newborns n (IG1) = 81 n (IG2) = 82 n (CG) = 84 n (RG) = 43 breastfed | Infant formula containing: IG1: 0.8 g/100 mL scGOS/lcFOS and B. breve M-16v (1 × 104 CFU/100 mL) IG2: 0.8 g/100 mL scGOS/lcFOS and B. breve M-16v (1 × 106 CFU/100 mL) | Infant formula | From birth till 6 weeks of age | Both synbiotic formulas (IG1 and IG2) increased the bifidobacteria proportions and decreased the prevalence of C. difficile. Fecal pH was significantly lower while L-lactate concentrations and acetate proportions were significantly higher in both intervention groups compared to RG |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín-Peláez, S.; Cano-Ibáñez, N.; Pinto-Gallardo, M.; Amezcua-Prieto, C. The Impact of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics during Pregnancy or Lactation on the Intestinal Microbiota of Children Born by Cesarean Section: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020341

Martín-Peláez S, Cano-Ibáñez N, Pinto-Gallardo M, Amezcua-Prieto C. The Impact of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics during Pregnancy or Lactation on the Intestinal Microbiota of Children Born by Cesarean Section: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022; 14(2):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020341

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín-Peláez, Sandra, Naomi Cano-Ibáñez, Miguel Pinto-Gallardo, and Carmen Amezcua-Prieto. 2022. "The Impact of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics during Pregnancy or Lactation on the Intestinal Microbiota of Children Born by Cesarean Section: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 14, no. 2: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020341

APA StyleMartín-Peláez, S., Cano-Ibáñez, N., Pinto-Gallardo, M., & Amezcua-Prieto, C. (2022). The Impact of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics during Pregnancy or Lactation on the Intestinal Microbiota of Children Born by Cesarean Section: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 14(2), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020341