Abstract

The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) provides reimbursements for nutritious foods for children with low-income at participating child care sites in the United States. The CACFP is associated with improved child diet quality, health outcomes, and food security. However CACFP participation rates are declining. Independent child care centers make up a substantial portion of CACFP sites, yet little is known about their barriers to participation. Researcher-led focus groups and interviews were conducted in 2021–2022 with 16 CACFP-participating independent centers and 5 CACFP sponsors across California CACFP administrative regions to identify participation benefits, barriers, and facilitators. Transcripts were coded for themes using the grounded theory method. CACFP benefits include reimbursement for food, supporting communities with low incomes, and healthy food guidelines. Barriers include paperwork, administrative reviews, communication, inadequate reimbursement, staffing, nutrition standards, training needs, eligibility determination, technological challenges, and COVID-19-related staffing and supply-chain issues. Facilitators included improved communication, additional and improved training, nutrition standards and administrative review support, online forms, reduced and streamlined paperwork. Sponsored centers cited fewer barriers than un-sponsored centers, suggesting sponsors facilitate independent centers’ CACFP participation. CACFP participation barriers should be reduced to better support centers and improve nutrition and food security for families with low-income.

1. Introduction

Rates of food insecurity for families with children under six years old living in the United States in 2021 are higher compared to families with older children or no children [1]. Food insecurity also disproportionately impacts households with incomes below 185 percent of the poverty threshold, single-parent families, and Black and Hispanic families [1]. Food insecurity in childhood is associated with negative health outcomes and behavioral, academic, and emotional problems [2,3]. Given that most US children under six years old spend time in nonparental care, child care settings are an ideal environment to support health equity by improving nutrition and food security for young children [4,5].

The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) is the largest federal nutrition program that contributes to the healthy growth and development of young children in child care settings in the United States [6]. Since 1968, the CACFP provides free nutrition training, access to commodity foods, and reimbursements for nutritious meals and snacks to income-eligible children at participating child care sites. Meals served at CACFP-participating sites are often more nutritious and better aligned with recommended child feeding practices compared to non-CACFP participating sites [7,8,9,10]. CACFP participation has been shown to improve child diet quality, health outcomes, and food insecurity [11,12].

Despite the benefits of the CACFP, participation rates are declining and many eligible child care sites do not participate. Nationally, the CACFP provided over 435 million meals in family child care homes and 1533 million meals in child care centers in 2019. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these numbers dropped to 356 million and 1436 million, respectively in 2021 [13]. Although this steep decline is likely related to pandemic-related closures of child care sites [14], CACFP participation trends were steadily declining prior to the pandemic. Specifically in California, there was a decline in CACFP participation between 2010–2017: more than 1.7 million fewer meals were served in child care centers and 8 million fewer meals were served in family child care homes [15]. These are concerning trends given the critical role that the CACFP plays in improving nutrition and food security for children from families with low-income. Research to understand the barriers to participating in the CACFP is just beginning to emerge [16,17,18].

Administrative oversight of the CACFP at the state level is managed by state departments. In California, the Department of Social Services began providing administrative CACFP oversight during the global COVID-19 pandemic as of 1 July 2021, taking over this role from the California Department of Education [19]. To administer the CACFP, the state may contract directly with a child care entity or contract with private, non-profit, or community-based third-party intermediaries—called sponsoring organizations. Sponsors may be entirely responsible for the administration of the food program for (a) one or more family child care homes; (b) two or more centers; (c) a center that is a legally distinct entity from the sponsoring organization (this is a sponsor of independent centers) or (d) any combination of the aforementioned [20]. Sponsoring organizations may provide the entities they sponsor with software to help them submit their CACFP-related paperwork.

Independent centers are defined by CDSS as an agency that operates a center at a single physical site. They are independently owned and operated and not owned by a corporation. Independent centers can either work with a sponsoring organization to operate the CACFP at their site, or enter into an agreement with the CDSS to assume financial and administrative responsibility for the CACFP operations [21]. A nationwide survey of CACFP-participating centers suggests approximately a third of the centers in the US are independent with an average of 97 children enrolled per center [22].

Studies specifically focusing on independent centers’ experience with the CACFP are limited [18,22]. Interviews conducted of independent center stakeholders across the United States in 2018 identified health and nutrition for children, reimbursement, guidance and trainings as key benefits of participating in CACFP [18]. Key challenges included paperwork, time, and insufficient training and education [18]. In a 2017 national U.S. survey of CACFP-participating centers, independent centers were more likely to use smaller, local grocery stores to procure foods and beverages, likely resulting in unique barriers to CACFP-participation compared to centers procuring foods through a foodservice provider or warehouse store [22].

The aim of this study is to identify benefits, barriers, and facilitators in accessing the CACFP experienced by sponsors of independent centers and by independent centers themselves in California—both those that contract with CDSS to operate the CACFP and those that work with a sponsoring organization to operate the CACFP—as well as explore opportunities for improvement. Independent child care centers and sponsors were selected as the focus because relatively little is known about their experiences with the CACFP. Findings were elucidated through qualitative analysis of researcher-led focus groups and one-on-one interviews with independent centers and sponsors of independent centers. The goal of this study is to inform state CACFP agencies and the USDA on how to better support independent centers in accessing the CACFP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection, Recruitment, and Enrollment

In August 2021, CDSS provided researchers with a database of CACFP-participating agencies in California. From this database, a geographically diverse sample of three types were selected and recruited into separate focus groups: independent centers that contract directly with the state to operate the CACFP (FG1), independent centers that work with a sponsoring organization to operate the CACFP (FG2), and sponsors of independent centers (FG3). The goal was to recruit at least 10 participants per focus group, including at least one military or government organization and one serving tribal communities for groups (1) and (2).

To ensure diverse geographical representation, site contact zip-codes were matched to the USDA 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes. RUCA codes were then categorized into urban, suburban, and rural [23]. Child care centers were assigned a random number, sorted in ascending order, and then filtered by RUCA code. A quota sampling method based on the proportion of centers’ RUCA codes in the original CDSS database was used to select the final centers for recruitment.

Recruitment materials were sent via email by the CACFP Roundtable, a program contact, or a sponsoring organization. Interested participants were asked to contact researchers to be screened and enrolled in the focus groups. Inclusion criteria required that participants: (1) be the person who manages the CACFP, (2) be 18 years old or older, (3) have access to a computer, tablet, or smartphone, and (4) be at a site that participated in the CACFP as an independent center or a sponsor of independent centers during the last 5 years.

After initial focus groups were conducted, the sample was expanded to ensure representation from critical participants. NPI requested an additional CDSS CACFP database pull in January 2022 and used convenience sampling methods to identify and recruit 16 centers that had participated in the CACFP for 1 to 3 years. This was to ensure that FG1 was inclusive of centers recently enrolled in the CACFP. Additionally, 21 centers from the original FG2 sample were identified whose sponsors participated in FG3 and who had not yet received recruitment material or contacted researchers. Finally, one sponsor was identified for direct recruitment from the original sample. These centers and sponsors were contacted by researchers by telephone.

Ultimately, we screened 22 centers for FG1, 15 centers for FG2, and 5 sponsors for FG3 for enrollment in the study. All centers were eligible and agreed to participate. Many enrolled participants were unable to attend the scheduled focus groups or a one-on-one interview. Final participants included: (1) FG1—11 individuals from 10 centers; 2 individuals participated in one focus group, 4 in a second focus group, 4 in a third focus group, and 1 in an individual interview; (2) FG2—7 individuals from 6 center; 6 participated in one focus group and 1 in an individual interview; all centers were sponsored by organizations in FG3; (3) FG3—6 individuals from 5 sponsoring organizations; 4 participated in 1 focus group, and 1 in an individual interview; 2 sponsors had centers in FG2. We achieved our pre-determined goals for variation in participant characteristics. Table 1 summarizes sample sizes by focus group.

Table 1.

Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) focus group recruitment sample and participation 1.

2.2. Surveys, Focus Groups and Structured Interviews

Enrolled participants—one from each center or sponsoring organization—were emailed a link to complete a 23-item (FG1/FG2) or 15-item (FG3) online survey (File S1) to capture demographics and site characteristics prior to participating in their scheduled focus group or interview. The surveys and interview guides were developed by researchers and reviewed by CDSS, the CACFP Roundtable, and CACFP-stakeholders. Topics included CACFP participation benefits, barriers, and what would help support CACFP participation. Questions were adjusted according to participants’ relationship with the CACFP (File S2). Participants received the questions (File S2) in advance of their scheduled focus group or interview, in addition to a glossary of terms commonly used in the CACFP. They were instructed to review these materials and seek answers to questions they were unable to answer themselves from other center or sponsor organization staff prior to attending their focus group or interview.

Each focus group session was led by a female peer-facilitator with over 20 years of experience as a center director working with the CACFP. A female PhD-level researcher (CH) from the research team also participated in the focus group sessions. The peer-facilitator was trained by CH on how to lead the focus groups. Each focus group lasted approximately 60–75 min and was conducted online using the Zoom video conferencing platform. Participants in all three groups (FG1, FG2 and FG3) were informed of the goal of the research project and the relationship of the interviewers to the project prior to answering questions. Participants who were unable to attend a scheduled focus group completed one-on-one interviews with the researcher using the same questions posed in the focus group. Focus groups and interviews were conducted December 2021 through March 2022. Participants received a $100 gift card for participating.

All discussions were audio-recorded, and field-notes were captured at the end of each focus group or interview. Each discussion was transcribed verbatim from audio recordings using Otter.AI (version 2022), then reviewed and cleaned by a researcher (DL) by removing vocal disfluencies–commonly known as filler words–and validating Otter.AI transcriptions against audio recordings. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. Participant survey and focus group responses were given a unique ID to maintain confidentiality.

2.3. Data Analysis

Survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics in Microsoft® Excel (version 16.62). The grounded theory method of analyzing qualitative data [24] informed transcript data coding, which was also conducted in Microsoft® Excel (version 16.62). Two coders (LB, CH) developed an initial coding of themes by reviewing the transcripts to create unique codes that summarized the main points of each participant’s response. A separate coder (DL) reviewed the initial codes developed by LB and CH. Dissimilar codes were reconciled and incorporated into refined coding protocol. DL then reviewed and compared codes to determine connections and created subthemes. Key quotes were extracted to provide context for the selected codes. Codes were then summarized into thematic categories. This final step was reviewed by the other coders (CH, LB) and principal investigator (LR) for final revisions. Participants did not provide feedback on thematic results.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Participant and site characteristics are listed in Table 2. Participants were mostly the center owner, director or site supervisor, all were women, and most were white, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latinx. Most participants had a Bachelor’s degree or higher with English as their preferred language. Centers and sponsors were mostly non-profit organizations. All served preschool age children; some also served infant/toddler or school-age children. Centers were predominantly urban and participated in the CACFP from a range of 1 to less than 3 years up to 10 or more years. Centers and sponsors were located across all CDSS-established CACFP regions and most were in operation for 5 or more years. Two centers in FG1 had previously participated in the CACFP through a sponsoring organization, and one center in FG2 had previously contracted directly with the state to operate the CACFP.

Table 2.

California Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) focus group participant and child care site or sponsoring organization characteristics 1.

Centers had an average of 14 staff. Sponsoring organizations had an average of 82 staff with 8 working in the CACFP departments. Most staff preferred using English. Children were predominantly English- or Spanish-preferring. A third to a half of the children at participating centers qualified for child care subsidies. Centers offered either full-day or both half- and full-day child care. The center director or supervisor was mostly responsible for both menu planning and CACFP administrative paperwork. One sponsored center worked with a sponsor that provided foodservice, and three FG3 sponsors provided their own foodservice. Nearly all centers offered at least breakfast and lunch, with several offering supper and some snacks throughout the day. Most centers prepared food on site at their center. Participants received support for the CACFP largely from the CACFP Roundtable (a non-profit organization), CDSS, or CDE (sponsors and centers that contract directly with the state). Centers working with sponsors mostly received support for the CACFP from their sponsoring organization.

3.2. Summary of Themes and Subthemes

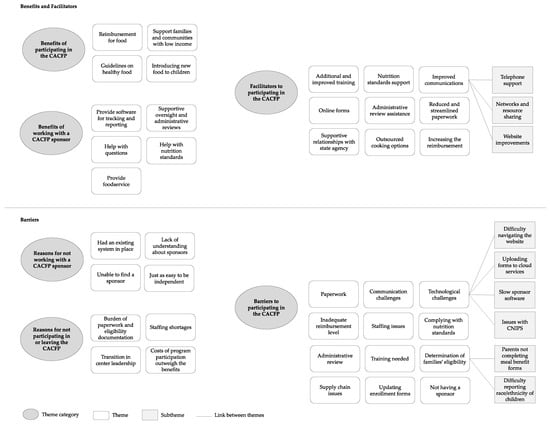

Qualitative analysis resulted in six major thematic categories: (1) benefits of the CACFP, (2) benefits of working with a CACFP sponsoring organization, (3) barriers to participating in the CACFP, (4) reasons why some independent centers do not participate in the CACFP or have left the program, (5) reasons independent centers do not work with a CACFP sponsoring organization, and (6) facilitators to participating in the CACFP. Within each category there are overarching themes and several subthemes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Emergent themes of benefits, barriers, and facilitators to participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) and working with CACFP sponsors, as identified by independent child care centers and their sponsors located in California, United States.

3.2.1. Benefits of Participating in the CACFP

Benefits of participating in the CACFP were numerous. Independent centers’ most cited CACFP benefit was reimbursement for food. Guidelines on healthy food and the ability to support families and communities with low-income also were often mentioned as benefits. For one center that works with a sponsoring organization, guidance was provided by a Registered Dietitian. Another center said that the CACFP facilitates them introducing new foods to children in their care. Themes are summarized with illustrative quotes in Table 3.

Table 3.

Emergent themes of benefits of participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) 1.

3.2.2. Benefits of Working with a CACFP Sponsoring Organization

Independent centers that work with a sponsoring organization cited many benefits of that relationship. The most cited benefits included: sponsors provide software for tracking and reporting, support oversight and administrative reviews, help with questions, and help with nutrition standards. Additionally, one center reported that the largest benefit was that their sponsor provided foodservice—meaning the meals and snacks provided to children were prepared and delivered by the sponsoring organization. One center that contracts directly with the state to operate the CACFP (but who previously worked with a sponsoring organization) stated that one of their biggest barriers to participating in the CACFP was not having a sponsor. Themes are summarized with illustrative quotes in Table 4.

Table 4.

Emergent themes of benefits of working with a CACFP sponsoring organization 1..

3.2.3. Barriers Related to Participating in the CACFP

Independent centers working with a sponsoring organization generally cited fewer barriers compared to independent centers contracting directly with the state. Paperwork was the barrier most often cited by sponsors and centers that contract directly with the state. This barrier was not cited by sponsored centers. Communication challenges were the second most frequent barrier cited by sponsors and sponsored centers. This barrier was not cited by independent centers that contract directly with the state. Communication challenges related specifically to information that sponsors and sponsored centers received about the CACFP.

Technological challenges were commonly cited by both types of independent centers and by sponsors. These technological challenges often dovetailed with communication challenges. Challenges related to navigating the website, specifically finding forms, were common for centers contracting directly with the state. In California sponsors and centers contracting directly with the state use the Child Nutrition Information and Payment System (CNIPS) to process claims for reimbursement. While most independent centers contracting directly with the state reported having no issues with CNIPS, one independent center contracting with the state and all five sponsors reported CNIPS being difficult to use and having outdated information and infrastructure. Staff technology literacy was a challenge cited by one center contracting directly with the state.

Independent centers working with a sponsoring organization cited slow software provided by the sponsor as a technological challenge. However, one center found the sponsor-provided software more helpful than having to submit CACFP-related paperwork in written/paper form. Issues uploading forms to an online electronic file hosting and sharing service and the cost of this technology were challenges cited by both sponsoring organizations and sponsored centers.

Inadequate reimbursement and staffing issues were other frequently cited barriers reported by both sponsors and centers contracting directly with the state. These two barriers were cited as being interlinked as for centers the CACFP provides partial reimbursement for food costs and no reimbursement for staffing for meal preparation or administration of the program (however, administrative expenses are allowable for sponsors). These two barriers were not cited by sponsored centers. Within the theme of inadequate reimbursement, one sponsored center cited sponsor fees as a barrier to participating in the CACFP.

Several additional barriers were cited, though less frequently. Complying with nutrition standards was a barrier cited by independent centers and sponsors. Administrative review was a barrier cited by both types of centers. Eligibility determination was another barrier cited by centers. This was mostly related to difficulty getting parents to complete meal benefit forms due to their hesitancy to disclose their income or failure of parents to indicate their child’s race/ethnicity on the form. Two independent centers were curious why eligibility is dependent on family income and one center perceived the eligibility income threshold as too high. Updating enrollment forms due to changing child care numbers was a barrier cited by only one independent center contracting directly with the state (two centers contracting directly with the state said that child enrollment decreased during COVID-19). Training was a barrier cited only by centers contracting directly with the state. Supply chain issues were a barrier cited only by independent centers contracting directly with the state and sponsors of independent centers. These issues were largely due to COVID-19 pandemic-related supply chain inconsistencies. Themes and subthemes are summarized with illustrative quotes in Table 5.

Table 5.

Emergent themes of barriers to participating in the CACFP 1.

3.2.4. Reasons Why Some Independent Centers Do Not Participate in the CACFP or Have Left the Program

Independent centers and sponsors cited several reasons why some centers do not participate in the CACFP or have left the program. When asked if they had ever discontinued participation in the CACFP, a majority of centers said no. One center contracting directly with the state said they were considering leaving the program due to staffing shortages. Another said they had previously discontinued enrollment due to a transition in center leadership. Sponsors cited several reasons why independent centers do not participate in the CACFP or have left the program, such as the burden of paperwork and eligibility documentation, and the costs of CACFP participation outweighing the benefits. Themes are summarized with illustrative quotes in Table 6.

Table 6.

Emergent themes of reasons why some independent centers do not participate in the CACFP or have left the program 1.

3.2.5. Reasons Independent Centers Do Not Work with a CACFP Sponsoring Organization

Independent centers that contract directly with the state cited several reasons for not working with a sponsoring organization. Many did not operate the CACFP through a sponsor because they had an existing system in place that helped them manage the program. One said that it was just as easy to be independent. Other reasons were lack of understanding about sponsors or being unable to find a sponsor. Themes are summarized with illustrative quotes in Table 7.

Table 7.

Emergent themes of reasons independent centers do not work with a CACFP sponsoring organization 1.

3.2.6. Facilitators to Participating in the CACFP

Improved communications was a major facilitator, containing several subthemes. Specifically, independent center participants requested telephone support and state website improvements, such as having a chat box on the state website. Sponsors also recommended having quarterly meetings among peers that allow for networking, shared resources, a dedicated CACFP website, and a more accurate and updated state CACFP listserv. Online forms were suggested by sponsors and both center types. Less paperwork and streamlined services were common suggestions by sponsors and sponsored centers. These themes were generally centered around tracking child enrollment and eligibility determination, and parents completing forms.

Centers commonly suggested continuing and/or expanding support for nutrition standards. Primary requests were for information on portion sizes, grocery shopping guides, sample menus, food recall information, and putting information in a digital format available online. Sponsors and centers mentioned improved training and administrative review assistance as additional facilitators. Two centers that contract directly with the state recommended having access to outsourced cooking options. A common theme for sponsors was the recommendation to have more supportive relationships with the state agency. Another recommendation to increase CACFP participation by independent centers was to increase the reimbursement rate. Themes and subthemes are summarized with illustrative quotes in Table 8.

Table 8.

Emergent themes of facilitators to participating in the CACFP 1.

4. Discussion

This study elucidated several benefits of, barriers to, and facilitators for participation in the CACFP by independent, licensed child care centers in California. A key benefit was offsetting the cost of nutritious foods served to children, particularly for low-income communities. However, many said that the amount of reimbursement was inadequate: it did not fully cover the cost of healthy meals or the necessary staff labor to support program administration. Despite appreciating the nutrition standards, some centers also found these to be a challenge: they didn’t fully understand the standards, they were unable to find foods that comply with these standards, children desired food that was not aligned with these standards, or they found it difficult to stay on top of changes to the standards. Both inadequate staffing and finding foods that adhered to the nutrition standards were heightened barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers related to the administrative work required to adhere to the CACFP were commonly cited by both centers and sponsors. Despite centers being able to submit paperwork online, the required paperwork was perceived as burdensome, particularly given levels of staffing. Specifically, eligibility determination and updating enrollment forms were perceived as barriers because families often were hesitant to disclose this information and centers did not want to guess race/ethnicity when not reported by parents. Communication and technological challenges dovetailed with the administrative barriers. These challenges stemmed from unclear communications from sponsors and the state agency about the CACFP requirements, difficulty navigating the state website to find the necessary forms, and difficulty uploading forms or providing information via CNIPS and online document sharing systems. Training staff on nutrition standards and administrative components was another barrier. Additionally, administrative reviews from the state agency that were perceived as punitive as opposed to supportive were cited as a barrier. Staffing shortages, burdensome paperwork, eligibility determinations, and the costs of participating in the CACFP outweighing the benefits were the main reasons why some centers opted to leave the CACFP, according to sponsors.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have exacerbated barriers to participation, many of these same benefits and barriers have been cited by other child care centers outside of California prior to the pandemic. A 2019 survey of centers in Connecticut showed that centers of all types perceived the CACFP as an important program to support them in serving nutritious meals to children, particularly those without sufficient food at home [17]. This study also cited inadequate reimbursement and the high cost of nutritious food as barriers to all types of centers in participating in CACFP and to adhering to nutrition standards [17]. These centers also cited reporting requirements, burdensome paperwork and difficulty collecting income eligibility forms from families as barriers [17]. In a 2018 study of independent centers across the US, centers also cited reimbursement, providing nutritious meals to children and guidance on healthy food as benefits of CACFP participation [18]. They also similarly cited burdensome paperwork, inadequate staff time, training, communication issues, administrative reviews, adherence to nutrition standards, and availability of foods that align with nutrition standards as barriers to participation [18].

Independent centers with sponsors in our study cited fewer barriers to participating in CACFP. However, those that didn’t work with a sponsor said they didn’t know this was an option or were unable to find a sponsor. Given the important role sponsors seem to play in supporting the participation of independent centers in the CACFP, efforts should be taken to improve centers’ awareness of and access to sponsoring organizations.

Centers in our study cited several seemingly feasible opportunities to facilitate participation in the CACFP: improving state agency communications by offering telephone support, improving the state’s website, and offering sponsors networking and resource sharing opportunities. Additional and improved training, providing support on nutrition standards and administrative reviews, providing more supportive relationships to sponsoring organizations, providing information on how to access outsourced cooking options, reduced and streamlined paperwork, and providing online forms for parents were also recommended. Many of these recommendations were also common in CACFP-participating independent centers from across the US [18]. Some of these recommendations may be actionable as the congressional actions required to increase reimbursement may be less feasible for immediate implementation.

Efforts to improve nutrition in child care settings are not unique to the U.S., especially as a majority of young children in the 38 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries are in child care by the time they are 3 years old [25]. Two reviews of international, federal nutrition standards for child care in the United Kingdom, the U.S., New Zealand, and Australia suggest a lack of consistency in standards between countries [26,27]. Two studies evaluating adherence to national policy for nutrition in child care settings in England, where child care is free for all 3- and 4-year-olds, shows regional variations in the interpretation of federal policy and the implementation of voluntary federal nutrition guidelines for child care [28,29]. New Zealand government policies encourage nutrition guidelines in child care, but food served in child care is not subsidized like in the U.S. through CACFP [30]. Ireland provides voluntary food and nutrition guidelines for childcare, but little research has been done to determine adherence to these guidelines [27]. In Australia, no national guidelines for nutrition in child care exist, however jurisdictional food provision guidelines are in place but are inconsistent across jurisdictions [31]. Researcher in other countries have identified challenges similar to those identified in our California study in terms of difficulty meeting nutrition guidelines and difficulty in accessing training for implementing nutrition guidelines [28,30].

This study has several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first study to look at the specific role sponsors of independent child care centers may play in alleviating barriers to CACFP participation. This study used a sampling method to ensure geographic and diverse representation of CACFP-participating independent centers and sponsors across the state. The study design of collecting qualitative data also provides more nuanced insight that survey research alone would be unable to accomplish.

This study has limitations. Given participants were only from California and a small subset of CACFP-participating sites, results may not be generalizable to CACFP-participating sites outside of California or sites other than independent child care centers. Despite attempts to recruit participants across all metropolitan regions, there were no sponsored centers from rural settings. Data were collected during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (December 2021–March 2022). As such, many potential participants may have been unable to participate given pandemic-related resource and time constraints, despite being offered a modest $100 incentive. Future studies should encourage participants to share barriers to CACFP participation that are not relevant to operations during a pandemic. Finally, although efforts were made to reduce social desirability bias, this is a general concern in qualitative research.

5. Conclusions

The CACFP supports improved nutrition and food security for young children with low-income by providing child care centers with reimbursement for healthy meals and snacks. Despite its perceived benefits by independent child care centers, several barriers to their participation in the CACFP exist. Compared to centers contracting directly with the state to operate the CACFP, sponsoring organizations appear to better support independent centers’ participation in the program. Numerous participant-recommended facilitators to CACFP participation exist. Efforts should be taken to implement these facilitators to reduce barriers to CACFP participation and increase independent child care centers’ awareness of and access to CACFP sponsoring organizations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu14214449/s1, File S1. Survey questions. File S2. Focus group/interview questions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.H.V., S.K.-D.M. and L.D.R.; methodology, D.L.L. and L.D.R.; software, D.L.L.; formal analysis, L.T.B., C.H., D.L.L. and L.D.R.; investigation, C.H., D.L.L. and L.D.R.; resources, E.H.V., S.K.-D.M. and L.D.R.; data curation, C.H. and D.L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.L.; writing—review and editing, C.H., L.T.B., L.D.R., E.H.V. and S.K.-D.M.; visualization, D.L.L.; supervision, L.D.R. and E.H.V.; project administration, D.L.L.; funding acquisition, E.H.V., S.K.-D.M. and L.D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the California Department of Social Services, contract number 21-7009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was reviewed by the University of California, Davis, Office of Research, Institutional Review Board Administration (study ID, 1778015-1) and was determined to be research not involving human subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The CACFP sponsors and child care centers that participated in the focus groups and interviews; our former child care center director peer-facilitator for help conducting the focus groups; California Department of Social Services, Child and Adult Care Food Program Branch and members of the stakeholder advisory board for reviewing survey and focus group questions and advising on participant recruitment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbit, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/104656/err-309.pdf?v=3317.9 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, P.; Chung, R.; Frank, D.A. Association of Food Insecurity with Children’s Behavioral, Emotional and Academic Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2017, 38, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Natzke, L. Early Childhood Program Participation: 2019. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020075REV (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Council on Community Pediatrics; Committee on Nutrition. Promoting Food Security for All Children. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA Food and Nutrition Services. Child and Adult Care Food Program. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Ritchie, L.D.; Boyle, M.; Chandran, K.; Spector, P.; Whaley, S.E.; James, P.; Samuels, S.; Hecht, K.; Crawford, P. Participation in the child and adult care food program is associated with more nutritious foods and beverages in child care. Child. Obes. 2012, 8, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinosho, T.; Vaughn, A.; Hales, D.; Mazzucca, S.; Gizlice, Z.; Ward, D. Participation in the Child and Adult Care Food Program Is Associated with Healthier Nutrition Environments at Family Child Care Homes in Mississippi. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzo, K.; Lee, D.L.; Ritchie, K.; Yoshida, S.; Homel Vitale, E.; Hecht, K.; Ritchie, L.D. Child Care Sites Participating in the Federal Child and Adult Care Food Program Provide More Nutritious Foods and Beverages. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chriqui, J.F.; Leider, J.; Schermbeck, R.M.; Sanghera, A.; Pugach, O. Changes in Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) Practices at Participating Childcare and Education Centers in the United States Following Updated National Standards, 2017–2019. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenman, S.; Abner, K.S.; Kaestner, R.; Gordon, R.A. The Child and Adult Care Food Program and the Nutrition of Preschoolers. Early Child. Res. Q. 2013, 28, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heflin, C.; Arteaga, I.; Gable, S. The Child and Adult Care Food Program and Food Insecurity. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2015, 89, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Food and Nutrition Services. Child Nutrition Tables. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/child-nutrition-tables (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Bauer, K.W.; Chriqui, J.F.; Andreyeva, T.; Kenney, E.L.; Stage, V.C.; Dev, D.; Lessard, L.; Cotwright, C.J.; Tovar, A. A Safety Net Unraveling: Feeding Young Children during COVID-19. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homel Vitale, E. Access to Food in Early Care Continues to Decline. Available online: https://nourishca.org/publications/report/access-to-food-in-early-care-continues-to-decline/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Andreyeva, T.; Henderson, K.E. Center-Reported Adherence to Nutrition Standards of the Child and Adult Care Food Program. Child. Obes. 2018, 14, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreyeva, T.; Sun, X.; Cannon, M.; Kenney, E.L. The Child and Adult Care Food Program: Barriers to Participation and Financial Implications of Underuse. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermbeck, R.M.; Kim, M.; Chriqui, J.F. Independent Early Childhood Education Centers’ Experiences Implementing the Revised Child and Adult Care Food Program Meal Pattern Standards: A Qualitative Exploratory Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 678–687.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AB-89 Budget Act of 2020—California Legislative Information. Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB89 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- California Department of Social Services. CACFP Manual Terms, Definitions and Acronyms. Available online: https://cdss.ca.gov/cacfp/resources/cacfp-manual-terms-definitions-and-acronyms (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- California Department of Social Services. CACFP Administrative Manual Section 1.3. Available online: https://cdss.ca.gov/cacfp/resources/cacfp-administrative-manual-section-13 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Chriqui, J.F.; Schermbeck, R.M.; Leider, J. Food Purchasing and Preparation at Child Day Care Centers Participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program in the United States, 2017. Child. Obes. 2018, 14, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washington State Department of Health. Guidelines for Using Rural-Urban Classification Systems for Community Health Assessment. Available online: https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/Documents/1500/RUCAGuide.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Foley, G.; Timonen, V. Using Grounded Theory Method to Capture and Analyze Health Care Experiences. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 50, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Education at a Glance 2016, OECD Indicators. Available online: http://edukacjaidialog.pl/_upload/file/2016_10/education_at_a_glance_2016.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Green, R.; Bergmeier, H.; Chung, A.; Skouteris, H. How are health, nutrition, and physical activity discussed in international guidelines and standards for children in care? A narrative review. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.; Kearney, J.; Hayes, N.; Slattery, C.G.; Corish, C. Healthy incentive scheme in the Irish full-day-care pre-school setting. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2014, 73, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttivant, H.; Knai, C. Improving food provision in child care in England: A stakeholder analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Neelon, S.E.; Burgoine, T.; Hesketh, K.R.; Monsivais, P. Nutrition practices of nurseries in England. Comparison with national guidelines. Appetite 2015, 85, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, S.; Dean, B.; Morton, S.M.B.; Wall, C.R. Do Childcare Menus Meet Nutrition Guidelines? Quantity, Variety and Quality of Food Provided in New Zealand Early Childhood Education Services. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Love, P.; Byrne, R.; Wakem, A.; Matwiejczyk, L.; Devine, A.; Golley, R.; Sambell, R. Childcare Food Provision Recommendations Vary across Australia: Jurisdictional Comparison and Nutrition Expert Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).