The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Food Security of UK Adults Aged 20–65 Years (COVID-19 Food Security and Dietary Assessment Study)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment

2.2. Equivalised Income and Income Quintiles

2.3. Food Security Measures

2.4. Shopping Habits and Food Spend

2.5. Energy and Nutrient Intakes

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

- Who was at risk of the experience of food insecurity?

3.1. Equivalised Household Income

“I follow a gluten free diet for coeliac disease, staple food availability was limited on the 2 weeks prior to 23rd march and for several weeks after”.

“I have coeliac disease and have been eating different brands of gluten free food during lockdown. I do not have a car so have had to use local stores. I’ve mostly shopped in small stores”

3.2. Employment Type

3.3. Following Government Guidelines on Isolating and Shielding

3.4. Concern for Food Availability

3.5. Eating Preferred Food by Food Security Status and Income Quintile

3.6. Differences in Household Income, Food Spend and Food Security Status

3.7. Change in Food Spend Amount per Week during the First UK Lockdown by Food Security Status

3.8. Proportion of Income Spent on Food and Relative Risk of Food Insecurity

3.9. Shopping Habits

3.10. Eating Habits

3.11. Coping Strategies

3.12. Diet Diaries, Nutrient Intakes, and Food Security Status

3.12.1. Energy for All Participants

3.12.2. Energy Intakes and BMI

3.12.3. Macronutrients

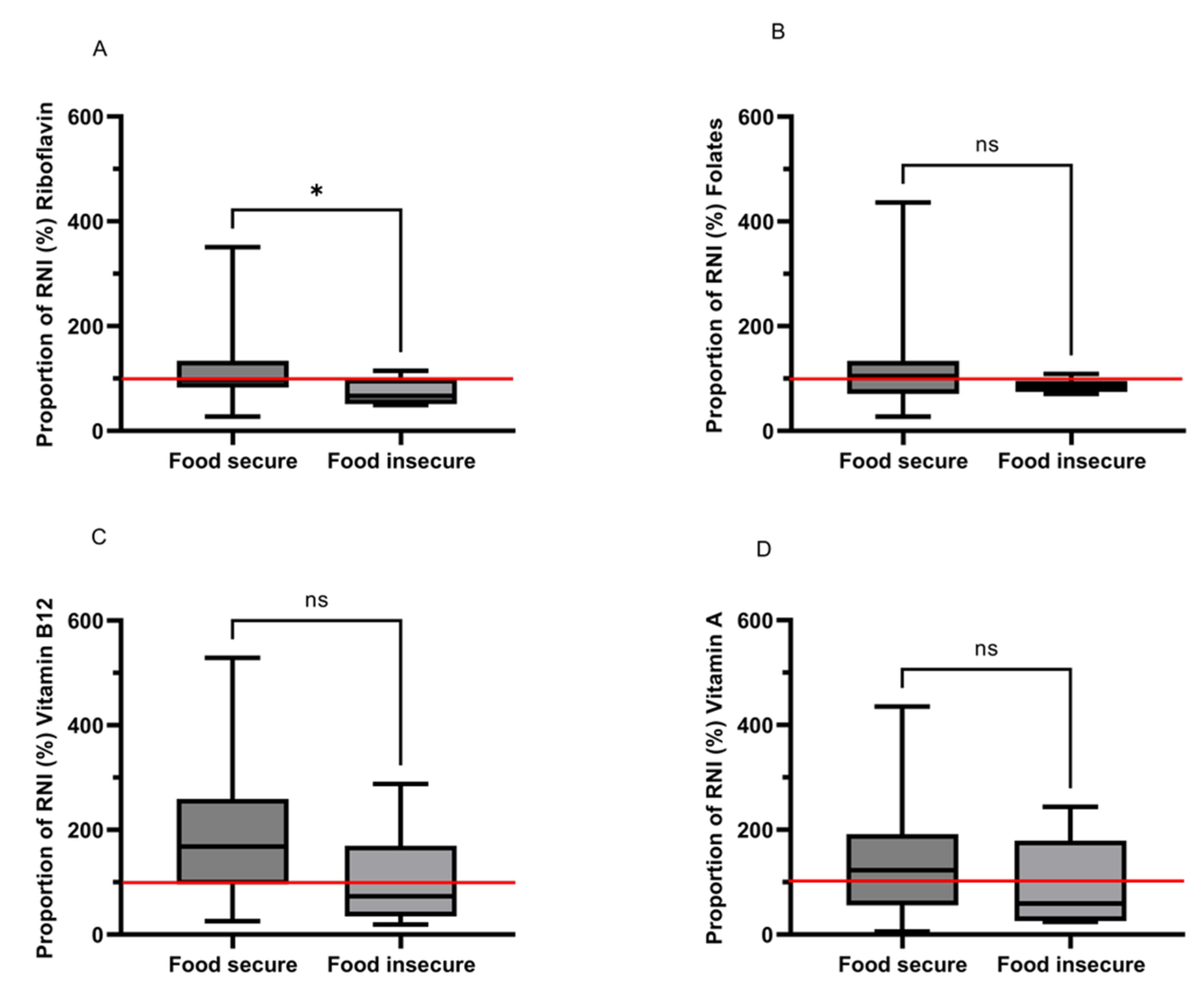

3.12.4. Micronutrients—Vitamins

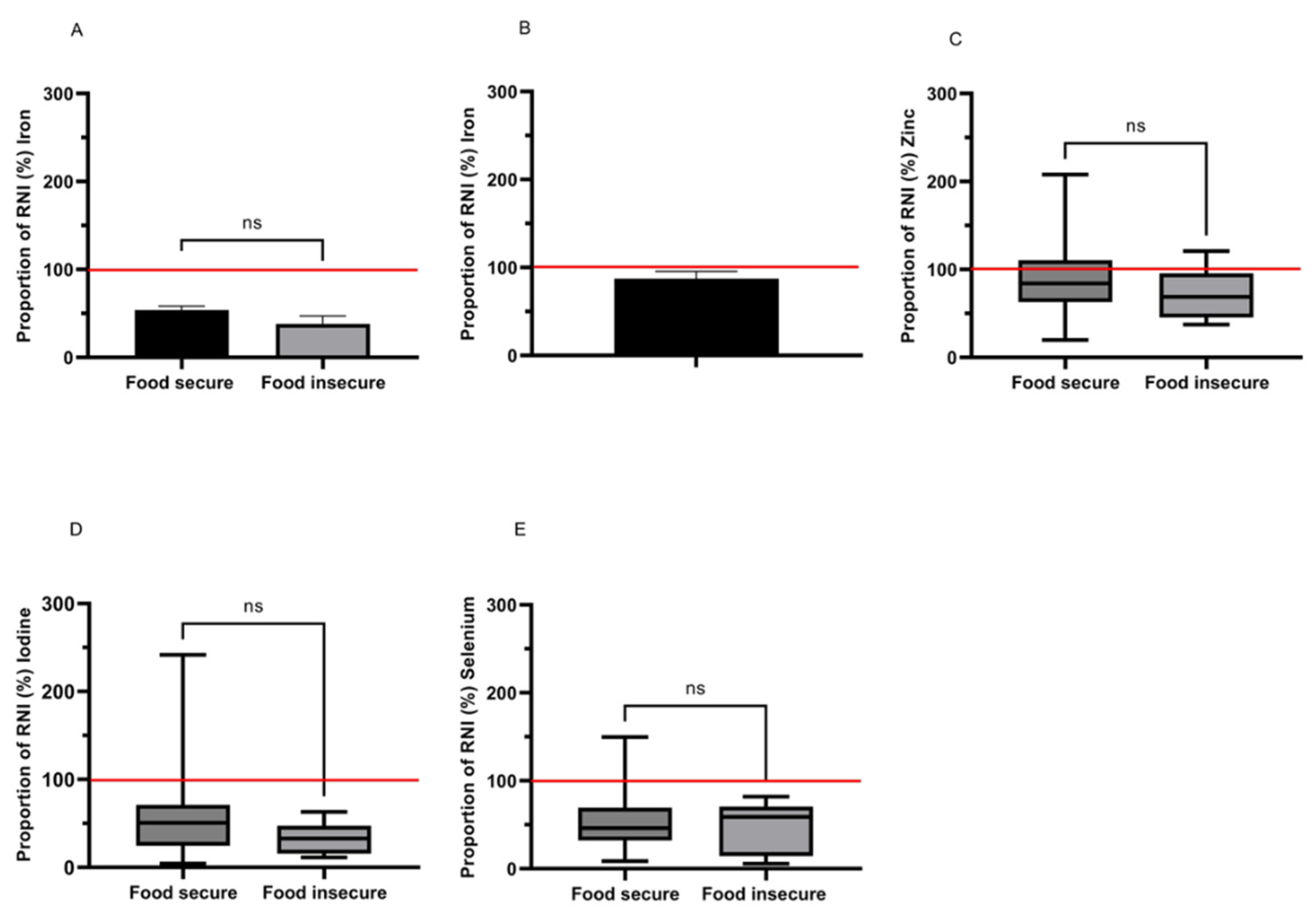

3.12.5. Micronutrients—Minerals

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

4.2. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prime Minister’s Statement on Coronavirus (COVID-19): 10 May 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-10-may-2020 (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Loopstra, R. Vulnerability to Food Insecurity since the COVID-19 Lockdown; The Food Foundation: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche, B.; Brassard, D.; Lapointe, A.; Laramée, C.; Kearney, M.; Côté, M.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Desroches, S.; Lemieux, S.; Plante, C. Changes in Diet Quality and Food Security among Adults during the COVID-19–Related Early Lockdown: Results from NutriQuébec. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 and Food Supply: Government Response to the Committee’s First Report—Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee-House of Commons. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmenvfru/841/84102.htm (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- The Ins and Outs of Government Small Business Grants. Available online: https://www.axa.co.uk/business-insurance/business-guardian-angel/government-grants-for-small-businesses-what-you-need-to-know/ (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Powell, A.; Francis-Devine, B.; Clark, H. Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme: Statistics; House of Commons Library: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mackley, A.; McInnes, R. Coronavirus: Universal Credit during the Crisis; House of Commons Library: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bentall, R.P.; Lloyd, A.; Bennett, K.; McKay, R.; Mason, L.; Murphy, J.; McBride, O.; Hartman, T.K.; Gibson-Miller, J.; Levita, L.; et al. Pandemic Buying: Testing a Psychological Model of over-Purchasing and Panic Buying Using Data from the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland during the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.; Doherty, B.; Pybus, K.; Pickett, K. How Covid-19 Has Exposed Inequalities in the UK Food System: The Case of UK Food and Poverty. Emerald Open Res. 2020, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, A.D.; Ngure, F.M.; Pelto, G.; Young, S.L. What Are We Assessing When We Measure Food Security? A Compendium and Review of Current Metrics. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- What Is Household Food Insecurity?|ENUF. Available online: https://enuf.org.uk/what-household-food-insecurity (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Liu, Y.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. Food Insecurity and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eicher-Miller, H.A. A Review of the Food Security, Diet and Health Outcomes of Food Pantry Clients and the Potential for Their Improvement through Food Pantry Interventions in the United States. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 220, 112871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nord, M.; Brent, C.P. Food Insecurity in Higher Income Households; US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; p. 50.

- Litton, M.M.; Beavers, A.W. The Relationship between Food Security Status and Fruit and Vegetable Intake during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, L.M.; Ryan, M.M.; O’Sullivan, T.A.; Lo, J.; Devine, A. Food-Insecure Household’s Self-Reported Perceptions of Food Labels, Product Attributes and Consumption Behaviours. Nutrients 2019, 11, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morales, M.E.; Berkowitz, S.A. The Relationship between Food Insecurity, Dietary Patterns, and Obesity. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, J.A.; Gans, K.M.; Risica, P.M.; Kirtania, U.; Strolla, L.O.; Fournier, L. How Is Food Insecurity Associated with Dietary Behaviors? An Analysis with Low Income, Ethnically Diverse Participants in a Nutrition Intervention Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 1906–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Avery, A. Food Insecurity and Malnutrition. Kompass Nutr. Diet. 2021, 1, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Cambridge, M.E.U. NatCen Social Research National Diet and Nutrition Survey Years 1–11, 2008–2019. [Data Collection], 19th ed.; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Household below Average Income Series: Quality and Methodology Information Report FYE 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/households-below-average-income-for-financial-years-ending-1995-to-2020/household-below-average-income-series-quality-and-methodology-information-report-fye-2020 (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Muellbauer, J. McClements on Equivalence Scales for Children. J. Public Econ. 1979, 12, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepshed, A. Inequality and Poverty; The Institute for Fiscal Studies: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide: Version 3: (576842013-001); American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Example of a Protocol for Identification of Misreporting (under- and Overreporting of Energy Intake) Based on the PILOT-PANEU Project. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dutch, D.C.; Golley, R.K.; Johnson, B.J. Diet Quality of Australian Children and Adolescents on Weekdays versus Weekend Days: A Secondary Analysis of the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2011–2012. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. Social Survey Division Annual Population Survey, April 2020–March 2021. [Data Collection], 2nd ed.; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2021.

- Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs National Statistics Family Food 2019/20. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/family-food-201920/family-food-201920 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Sharma, S.V. Social Determinants of Health–Related Needs During COVID-19 Among Low-Income Households With Children. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2020, 17, 33006541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, L.A.; Rogus, S. Impact of Employment, Essential Work, and Risk Factors on Food Access during the COVID-19 Pandemic in New York State. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raifman, J.; Bor, J.; Venkataramani, A. Association Between Receipt of Unemployment Insurance and Food Insecurity Among People Who Lost Employment During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2035884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitor, F.; Doerr, C.; Kehl, S. Unemployment, SNAP Enrollment, and Food Insecurity Before and After California’s COVID-19 Shutdown. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogundijo, D.A.; Tas, A.A.; Onarinde, B.A. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Eating and Purchasing Behaviours of People Living in England. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Leung, C.W. Food Insecurity and COVID-19: Disparities in Early Effects for US Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus and the Impact on UK Households and Businesses—Office for National Statistics. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/uksectoraccounts/articles/coronavirusandtheimpactonukhouseholdsandbusinesses/2021 (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee. COVID-19 and the Issues of Security in Food Supply; House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee: London, UK, 2021; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Tesco Shows How It Adapted as Shoppers Moved Online Fast during the Covid-19 Lockdown—And Counts the Costs of Change. Available online: https://internetretailing.net/covid-19/covid-19/tesco-shows-how-it-adapted-as-shoppers-moved-online-fast-during-the-covid-19-lockdown--and-counts-the-costs-of-change-21616 (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- UK Online Grocery Growth Clicks up as Lockdown Trends Continue. Available online: https://www.kantar.com/uki/inspiration/fmcg/uk-online-grocery-growth-clicks-up-as-lockdown-trends-continue (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Spurlock, C.A.; Todd-Blick, A.; Wong-Parodi, G.; Walker, V. Children, Income, and the Impact of Home Delivery on Household Shopping Trips. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Grocery Shopping Behaviours; Public Health England: London, UK, 2022; p. 38.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs United Kingdom Food Security Report 2021: Contents. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/united-kingdom-food-security-report-2021/united-kingdom-food-security-report-2021-contents (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Kent, K.; Murray, S.; Penrose, B.; Auckland, S.; Horton, E.; Lester, E.; Visentin, D. The New Normal for Food Insecurity? A Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey over 1 Year during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Baidya, A.; Aaron, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, C.; Wetzler, E. Differences in the Early Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Livelihoods in Rural and Urban Areas in the Asia Pacific Region. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 31, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites-Zapata, V.A.; Urrunaga-Pastor, D.; Solorzano-Vargas, M.L.; Herrera-Añazco, P.; Uyen-Cateriano, A.; Bendezu-Quispe, G.; Toro-Huamanchumo, C.J.; Hernandez, A.V. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Food Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niles, M.T.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.H.; Wentworth, T.; Biehl, E.; Neff, R. The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán-Rossi, P.; Vilar-Compte, M.; Teruel, G.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Food Insecurity Measurement and Prevalence Estimates during the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey in Mexico. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dondi, A.; Candela, E.; Morigi, F.; Lenzi, J.; Pierantoni, L.; Lanari, M. Parents’ Perception of Food Insecurity and of Its Effects on Their Children in Italy Six Months after the COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak. Nutrients 2021, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A. Fat and Sugar: An Economic Analysis. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 838S–840S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Food Prices Tracking: July Update|Food Foundation. Available online: https://foodfoundation.org.uk/news/food-prices-tracking-july-update (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs Data for Chart 2.2: Trend in Share of Spend Going on Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages in Low Income and All UK Households, 2003-04 to 2018-19-GOV.UK. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908880/foodstatisticspocketbook-shareofspendonfood-13aug20.csv/preview (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Connors, C.; Malan, L.; Canavan, S.; Sissoko, F.; Carmo, M.; Sheppard, C.; Cook, F. The Lived Experience of Food Insecurity under Covid-19. In A Bright Harbour Collective Report for the Food Standards Agency; Food Standard Agency: London, UK, 2020; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.; Jitendra, A.; Rabindrakumar, S. 5 Weeks Too Long: Why We Need to End the Wait for Universal Credit; The Trussell Trust: Salisbury, UK, 2019; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- The Food Foundation Government Data Shows £20 Uplift Is Likely to Have Protected People on Universal Credit from Food Insecurity|Food Foundation. Available online: https://foodfoundation.org.uk/press-release/government-data-shows-ps20-uplift-likely-have-protected-people-universal-credit-food (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- School Food Matters Food Insecurity during Lockdown. Available online: https://www.schoolfoodmatters.org/news-views/news/food-insecurity-during-lockdown (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Fuller, E.; Urszula, B.; Davies, B.; Mandalia, D.; Stocker, B. The Food and You Survey—Wave 5; Food Standard Agency: London, UK, 2019; p. 96.

- Powers, H.J.; Hill, M.H.; Mushtaq, S.; Dainty, J.R.; Majsak-Newman, G.; Williams, E.A. Correcting a Marginal Riboflavin Deficiency Improves Hematologic Status in Young Women in the United Kingdom (RIBOFEM). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prentice, A.M.; Bates, C.J. A Biochemical Evaluation of the Erythrocyte Glutathione Reductase (EC 1.6.4.2) Test for Riboflavin Status. 2. Dose-Response Relationships in Chronic Marginal Deficiency. Br. J. Nutr. 1981, 45, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.; Tomar, S.K.; Singh, A.K.; Mandal, S.; Arora, S. Riboflavin and Health: A Review of Recent Human Research. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3650–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, H.J. Riboflavin (Vitamin B-2) and Health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shipton, M.J.; Thachil, J. Vitamin B12 Deficiency—A 21st Century Perspective. Clin. Med. 2015, 15, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vahid, F.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Mirmajidi, S.; Doaei, S.; Rahmani, D.; Faghfoori, Z. Association Between Index of Nutritional Quality and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: The Role of Vitamin D and B Group. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 358, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaric, B.L.; Obradovic, M.; Bajic, V.; Haidara, M.A.; Jovanovic, M.; Isenovic, E.R. Homocysteine and Hyperhomocysteinaemia. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 2948–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanumihardjo, S.A.; Russell, R.M.; Stephensen, C.B.; Gannon, B.M.; Craft, N.E.; Haskell, M.J.; Lietz, G.; Schulze, K.; Raiten, D.J. Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development (BOND)-Vitamin A Review. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1816S–1848S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thurnham, D.I.; McCabe, G.P.; Northrop-Clewes, C.A.; Nestel, P. Effects of Subclinical Infection on Plasma Retinol Concentrations and Assessment of Prevalence of Vitamin A Deficiency: Meta-Analysis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2003, 362, 2052–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marley, A.; Smith, S.C.; Ahmed, R.; Nightingale, P.; Cooper, S.C. Vitamin A Deficiency: Experience from a Tertiary Referral UK Hospital; Not Just a Low- and Middle-Income Country Issue. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 6466–6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All | Food Secure | Food Insecure | p Value | ||||||||

| n | Median | 25th–75th Percentile | n | Median | 25th–75th Percentile | n | Median | 25th–75th Percentile | |||

| Age (years) | 515 | 44.0 | 33–52 | 421 | 45.0 | 33–54 | 94 | 41.0 | 33–50 | 0.031 * | |

| Height (m) | Male | 77 | 1.80 | 1.75–1.85 | 62 | 1.80 | 1.75–1.85 | 15 | 1.80 | 1.78–1.85 | 0.395 |

| Female | 423 | 1.65 | 1.61–1.70 | 346 | 1.65 | 1.61–1.70 | 77 | 1.63 | 1.61–1.68 | 0.095 | |

| Missing | 14 | n/a | n/a | 12 | n/a | n/a | 2 | n/a | n/a | ||

| Weight (kg) | Male | 78 | 85.1 | 75.0–99.5 | 63 | 84.6 | 76.0–96.2 | 15 | 86.0 | 74.0–119.0 | 0.506 |

| Female | 412 | 66.0 | 59.9–78.0 | 336 | 66.0 | 60.0–77.4 | 76 | 67.3 | 58.2–81.8 | 0.837 | |

| Missing | 24 | n/a | n/a | 21 | n/a | n/a | 3 | n/a | n/a | ||

| BMI | Male | 76 | 26.1 | 23.7–30.1 | 61 | 25.9 | 23.7–29.8 | 15 | 27.1 | 23.1–31.1 | 0.681 |

| Female | 403 | 24.3 | 21.6–28.3 | 329 | 24.2 | 21.7–28.1 | 74 | 24.8 | 20.9–28.8 | 0.789 | |

| Missing | 35 | n/a | n/a | 30 | n/a | n/a | 5 | n/a | n/a | ||

| Equivalised income per week (£) | 470 | 853.69 | 551.69–1182.20 | 385 | 853.69 | 580.56–1243.71 | 85 | 763.83 | 288.69–1123.28 | 0.038 * | |

| Food spend per week (£) | 468 | 86.51 | 59.74–116.33 | 383 | 86.06 | 60.19–115.02 | 85 | 89.32 | 57.13–124.14 | 0.582 | |

| Proportion of income (%) | 466 | 9.9 | 6.4–16.3 | 381 | 9.5 | 5.7–15.4 | 85 | 11.04 | 7.3–21.7 | 0.011 * | |

| Household size | 512 | 2.0 | 2.0–4.0 | 418 | 2.0 | 2.0–4.0 | 94 | 3.0 | 2.0–4.0 | 0.140 | |

| Sex | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |||||

| Male | 79 | (15.3) | 64 | (15.2) | 15 | (16.0) | 0.861 | ||||

| Female | 435 | (84.5) | 356 | (84.6) | 79 | (84.0) | |||||

| Missing | 1 | (0.2) | 1 | (0.2) | n/a | n/a | |||||

| Income quintiles | 1 (<£25,700.47) | 98 | (20.9) | 72 | (18.7) | 26 | (30.6) | 0.117 | |||

| 2 (>£25,700.47) | 90 | (19.1) | 75 | (19.5) | 15 | (17.6) | |||||

| 3 (>£39,643.18) | 99 | (21.1) | 80 | (20.8) | 19 | (22.4) | |||||

| 4 (>£53,277.87) | 84 | (17.9) | 73 | (19) | 11 | (12.9) | |||||

| 5 (>£75,503.02) | 99 | (21.1) | 85 | (22.1) | 14 | (16.5) | |||||

| Income Quintile (per Year (£)) | n | (%) ǂ | RR | (CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (<£25,700.47) | 26 | (30.6) | 1.6 | (1.1–2.4) | 0.015 * |

| 2 (>£25,700.47) | 15 | (17.6) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.5) | 0.697 |

| 3 (>£39,643.18) | 19 | (22.4) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 0.747 |

| 4 (>£53,277.87) | 11 | (12.9) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) | 0.190 |

| 5 (>£75,503.02) | 14 | (16.5) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) | 0.251 |

| Employment Status | Relative Risk (RR) of Food Insecurity If in Listed Employment before Lockdown RR (95% CI) | Relative Risk (RR) of Food Insecurity If in Listed Employment during Lockdown RR (95% CI) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (n) Ŧ | (%) ǂ | RR | CI | p Value | n | (n) Ŧ | (%) ǂ | RR | CI | p Value | |

| Self-Employed | 44 | (12) | (27.3) | 1.6 | (0.9–2.6) | 0.105 | 35 | (11) | (31.4) | 1.8 | (1.1–3.1) | 0.037 * |

| Part-time employment | 93 | (12) | (12.9) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) | 0.140 | 82 | (9) | (11.0) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.1) | 0.063 |

| Full-time employment | 328 | (55) | (16.8) | 0.8 | (0.6–1.2) | 0.248 | 273 | (45) | (16.5) | 0.8 | (0.6–1.2) | 0.270 |

| Unable to work due to disability | 6 | (3) | (50.0) | 2.8 | (1.2–6.4) | 0.043 *,¥ | 8 | (4) | (50.0) | 2.8 | (1.4–5.8) | 0.019 *¥ |

| Unable to work due to sickness | 3 | (3) | (100.0) | 5.6 | (4.7–6.8) | <0.001 *,¥ | 5 | (3) | (60.0) | 3.4 | (1.6–7.0) | 0.015 *¥ |

| Unable to work as unemployed/seeking work | 9 | (5) | (55.6) | 3.2 | (1.7–5.8) | 0.003 *¥ | 18 | (8) | (44.4) | 2.6 | (1.5–4.5) | 0.003 ¥ |

| Homemaker/full-time parent | 15 | (3) | (25.0) | 1.1 | (0.4–3.1) | 0.859 ¥ | 19 | (5) | (26.3) | 1.5 | (0.7–3.2) | 0.354 ¥ |

| Furloughed worker | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 52 | (10) | (19.2) | 1.1 | (0.6–1.9) | 0.847 |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | (1) | (50.0) | 2.8 | (0.7–11.2) | 0.244 ¥ | 2 | (1) | (50.0) | 2.8 | (0.7–11.2) | 0.244 ¥ |

| QN | Relative Risk (RR) Of Food Insecurity If in Listed Government Guidelines | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Ŧ (n) | ǂ (%) | RR | (CI) | p Value | ||

| 1 | Not self-isolating but following government guidance on social distancing | 442 | (72) | (16.3) | 0.5 | (0.4–0.8) | 0.005 * |

| 2 | Self-isolating for 7 days, following symptoms | 2 | (1) | (50.0) | 2.8 | (0.7–11.2) | 0.244 |

| 3 | Self-isolating for longer than 7 days following symptoms, because you still have a temperature (above 37.8 °C) | 1 | (1) | (100.0) | 5.5 | (4.6–6.6) | 0.034 *,¥ |

| 4 | Self-isolating for LONGER than 14 days following symptoms in a member of your household, because YOU have developed symptoms during this time | 0 | (0) | (0.0) | n/a | n/a | 0.636 ¥ |

| 5 | Not leaving your home because you are at a VERY HIGH RISK of COVID-19 and have received a letter from the NHS (Shielding) | 9 | (1) | (11.1) | 0.6 | (0.1–3.9) | 0.313 ¥ |

| 6 | Not leaving your home except to get essential items such as food and medicine because you are at HIGH RISK of COVID-19, e.g., are 70 or older, pregnant, have diabetes, taking medication that can affect your immune system. | 27 | (9) | (50.0) | 1.9 | (1.1–3.4) | 0.037 *,¥ |

| 7 | Not leaving your home because someone in the household is more vulnerable to the virus (i.e., not high risk but at greater risk) | 38 | (12) | (31.6) | 1.8 | (1.1–3.1) | 0.027 * |

| 8 | Status isolating or not Prefer not to say | 3 | (0) | (0.0) | n/a | n/a | 0.412 ¥ |

| Food Spend Change Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | Stayed Same | Decrease | p Value | |||

| Total | n | 174 | 209 | 83 | ||

| Percentage of income spent on food (%) | 11.5 a | 8.74 b | 9.2 b | 0.001 ** | ||

| Percentage of group (%) | (37.3) | (44.8) | (17.8) | |||

| Change in food spend (£) | +33.57 | 0 | −30.31 | |||

| EQVINC Weekly income (£) | Median | 853.69 | 853.69 | 878.11 | 0.380 | |

| 25th | 597.11 | 530.07 | 584.1 | |||

| 75th | 1297.42 | 1182.2 | 1129.32 | |||

| Food secure | n | 144 | 174 | 63 | ||

| Percentage of income spent on food (%) | 11.4 a | 7.9 b | 9.2b | <0.001 ** | ||

| Percentage of group (%) | (37.8) | (45.7) | (16.0) | |||

| Change in food spend (£) | +32.38 | 0 | −28.88 | |||

| EQVINC Weekly income (£) | Median | 853.69 | 853.69 | 853.69 | 0.716 | |

| 25th | 609.97 | 575.49 | 548.52 | |||

| 75th | 1279.16 | 1269.49 | 1176.70 | |||

| Food insecure | n | 30 | 35 | 20 | ||

| Percentage of income spent on food (%) | 14.3 a | 10.6 a,b | 8.4 b | 0.047 * | ||

| Percentage of group (%) | (35.3) | (41.2) | (23.5) | |||

| Change in food spend (£) | +39.89 | 0 | −35.9 | |||

| EQVINC Weekly income (£) | Median | 891.17 | 561.51 | 909.56 | 0.028 * | |

| 25th | 520.34 | 225.86 | 629.03 | |||

| 75th | 1366.22 | 935.85 | 1024.57 | |||

| p Value | Food secure v food insecure percentage of income | 0.151 | 0.003 * | 0.866 | ||

| p Value | Food secure v food insecure Change in EQVINC Weekly income (£) | 0.780 | 0.002 * | 0.802 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thomas, M.; Eveleigh, E.; Vural, Z.; Rose, P.; Avery, A.; Coneyworth, L.; Welham, S. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Food Security of UK Adults Aged 20–65 Years (COVID-19 Food Security and Dietary Assessment Study). Nutrients 2022, 14, 5078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235078

Thomas M, Eveleigh E, Vural Z, Rose P, Avery A, Coneyworth L, Welham S. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Food Security of UK Adults Aged 20–65 Years (COVID-19 Food Security and Dietary Assessment Study). Nutrients. 2022; 14(23):5078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235078

Chicago/Turabian StyleThomas, Michelle, Elizabeth Eveleigh, Zeynep Vural, Peter Rose, Amanda Avery, Lisa Coneyworth, and Simon Welham. 2022. "The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Food Security of UK Adults Aged 20–65 Years (COVID-19 Food Security and Dietary Assessment Study)" Nutrients 14, no. 23: 5078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235078

APA StyleThomas, M., Eveleigh, E., Vural, Z., Rose, P., Avery, A., Coneyworth, L., & Welham, S. (2022). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Food Security of UK Adults Aged 20–65 Years (COVID-19 Food Security and Dietary Assessment Study). Nutrients, 14(23), 5078. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235078