Design of Culturally and Linguistically Tailored Nutrition Education Materials to Promote Healthy Eating Habits among Pakistani Women Participating in the PakCat Program in Catalonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultural and Linguistic Adaptation of Nutrition Education Material for the Intervention Group

2.1.1. Session 1: Why Us? The Most Common Health Problems of the Pakistani Population

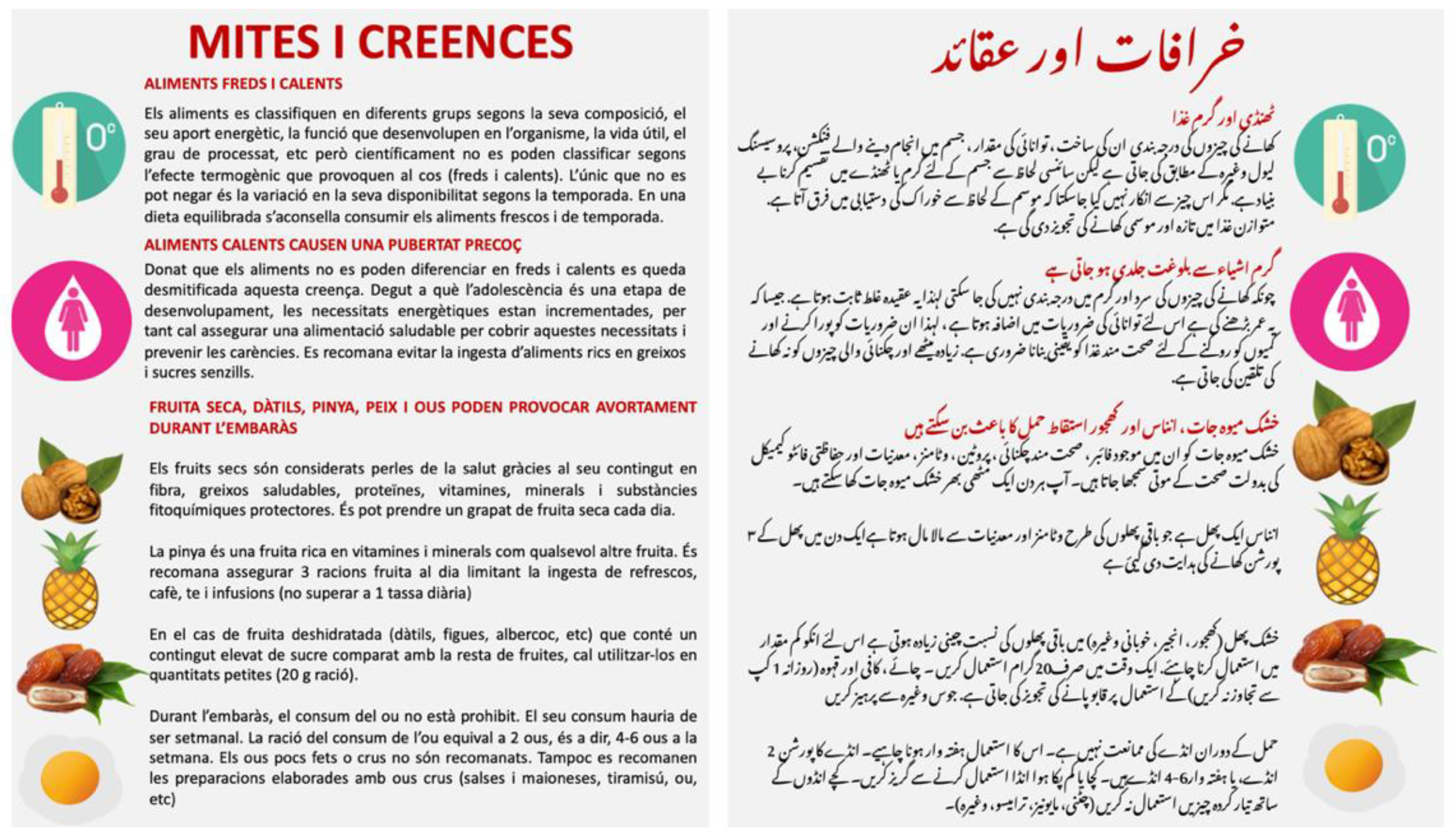

2.1.2. Session 2: Food Myths and Beliefs: What Does Science Say?

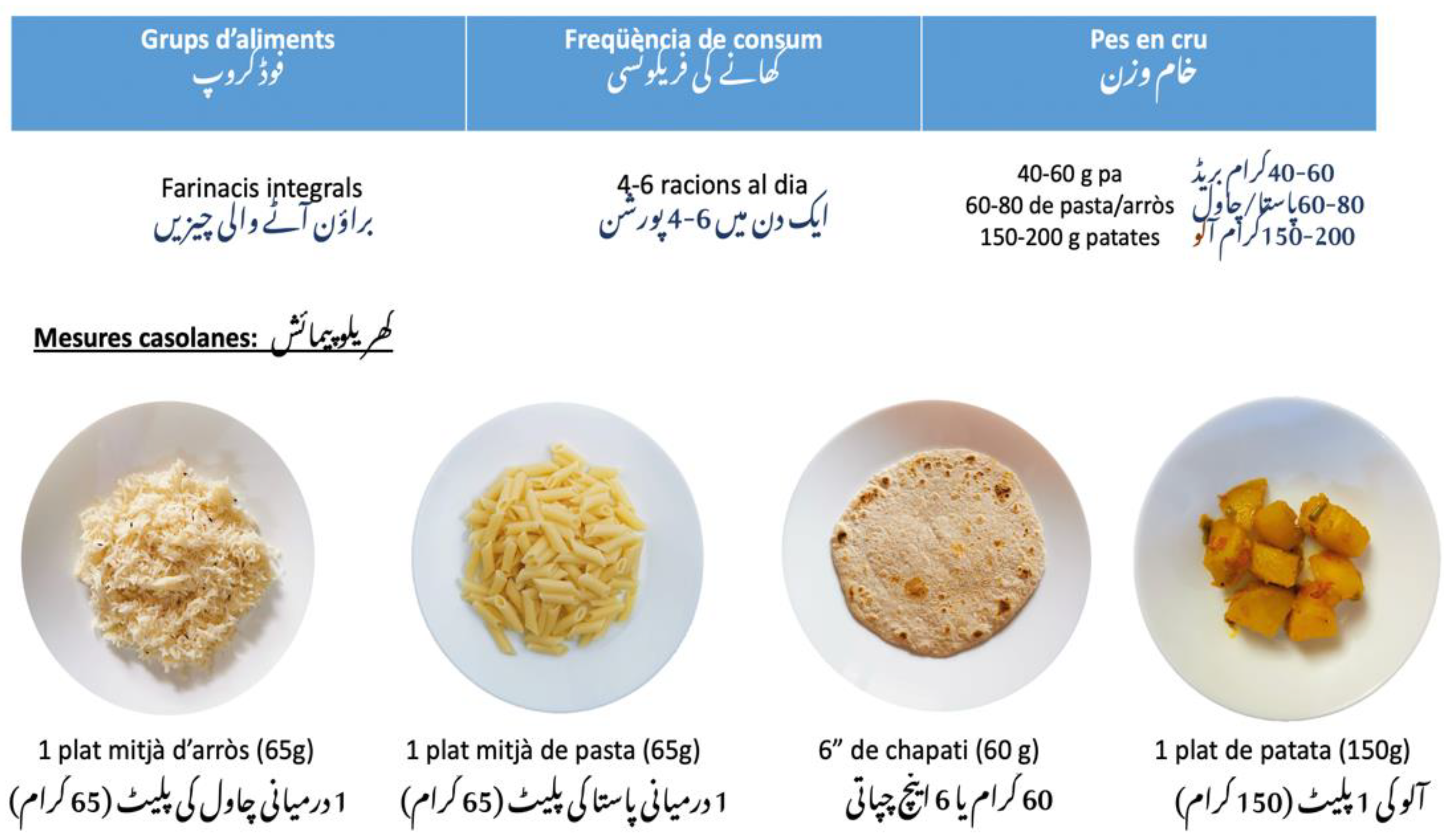

2.1.3. Sessions 3: What Is a Healthy Diet?

2.1.4. Sessions 4: The Value of Our Traditional Pakistani Diet

2.1.5. Sessions 5: Small Changes to Eat Better (MORE)

2.1.6. Small Changes to Eat Better (CHANGE)

2.1.7. Small Changes to Eat Better (LESS)

2.1.8. Let us Plan Our Weekly Food Purchase!

2.1.9. How to Plan a Balanced Menu?

2.1.10. Photovoice

2.2. Cultural and Linguistic Adaptation of Nutrition Education Material for the Control Group

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beltrán-Antolín, J.; Sáiz-López, A. La comunidad pakistaní en España. Anuario Asia-Pacífico; Barcelona Centre for International Affaris (CIDOB). 2007, pp. 407–416. Available online: https://www.cidob.org/articulos/anuario_asia_pacifico/2007/la_comunidad_pakistani_en_espana (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Foreign Population by Country of Nationality, Age (Five-Year Groups), and Sex. 2021. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=36825&L=1 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Statistical Institute of Catalonia. Foreign Population by Provinces. 2021. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/poblacioestrangera/?geo=cat&nac=d426&b=2&lang=en (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Statical Institute of Catalonia. Foreign Population by Age and Sex. 2021. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/poblacioestrangera/?geo=cat&nac=d426&b=1&lang=en (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Güell, B.; Martínez, R.; Naz, K.; Solé, A. Barcelonines d’origen Pakistanѐs: Empoderament i Participació Contra la Feminització de la Pobresa; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Catalonia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Satish, P.; Vela, E.; Bilal, U.; Cleries, M.; Kanaya, A.M.; Kandula, N.; Virani, S.S.; Islam, N.; Valero-Elizondo, J.; Yahya, T.; et al. Burden of cardiovascular risk factors and disease in five Asian groups in Catalonia: A disaggregated, population-based analysis of 121 000 first-generation Asian immigrants. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellin-Olsen, T.; Wandel, M. Changes in food habits among Pakistani immigrant women in Oslo, Norway. Ethn. Health 2005, 10, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, E.; Burton, N.W.; Anderssen, S.A. Physical activity levels six months after a randomised controlled physical activity intervention for Pakistani immigrant men living in Norway. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhopal, R.S.; Douglas, A.; Wallia, S.; Forbes, J.F.; Lean, M.E.; Gill, J.M.; McKnight, J.A.; Sattar, N.; Sheikh, A.; Wild, S.H.; et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention on weight change in south Asian individuals in the UK at high risk of type 2 diabetes: A family-cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenum, A.K.; Brekke, I.; Mdala, I.; Muilwijk, M.; Ramachandran, A.; Kjøllesdal, M.; Andersen, E.; Richardsen, K.R.; Douglas, A.; Cezard, G.; et al. Effects of dietary and physical activity interventions on the risk of type 2 diabetes in South Asians: Meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised controlled trials. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujral, U.P.; Kanaya, A.M. Epidemiology of diabetes among South Asians in the United States: Lessons from the MASALA study. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1495, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandula, N.R.; Bernard, V.; Dave, S.; Ehrlich-Jones, L.; Counard, C.; Shah, N.; Kumar, S.; Rao, G.; Ackermann, R.; Spring, B.; et al. The South Asian Healthy Lifestyle Intervention (SAHELI) trial: Protocol for a mixed-methods, hybrid effectiveness implementation trial for reducing cardiovascular risk in South Asians in the United States. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 92, 105995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousar, R.; Burns, C.; Lewandowski, P. A culturally appropriate diet and lifestyle intervention can successfully treat the components of metabolic syndrome in female Pakistani immigrants residing in Melbourne, Australia. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2008, 57, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Bhairappa, S.; Prasad, S.R.; Manjunath, C.N. Clinical characteristics, angiographic profile and in hospital mortality in acute coronary syndrome patients in South Indian population. Heart India 2014, 2, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, N.; Wasti, S.P. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in South Asia: A systematic review. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2016, 36, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Jackson, R.T. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome among low-income South Asian Americans. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafar, T.H.; Levey, A.S.; White, F.M.; Gul, A.; Jessani, S.; Khan, A.Q.; Jafary, F.H.; Schmid, C.H.; Chaturvedi, N. Ethnic differences and determinants of diabetes and central obesity among South Asians of Pakistan. Diabet. Med. A J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2004, 21, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, N.; Gill, J.M. Type 2 diabetes in migrant south Asians: Mechanisms, mitigation, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.D.; Gupta, P.; Mp, G.; Roy, A.; Qamar, A. Risk factors for myocardial infarction in very young South Asians. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2020, 27, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gask, L.; Aseem, S.; Waquas, A.; Waheed, W. Isolation, feeling ‘stuck’ and loss of control: Understanding persistence of depression in British Pakistani women. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 128, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himmelgreen, D.A.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Martinez, D.; Bretnall, A.; Eells, B.; Peng, Y.; Bermúdez, A. The longer you stay, the bigger you get: Length of time and language use in the U.S. are associated with obesity in Puerto Rican women. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2004, 125, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.S.; Bjørge, B.; Hjellset, V.T.; Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; Råberg, M.; Wandel, M. Changes in food habits and motivation for healthy eating among Pakistani women living in Norway: Results from the InnvaDiab-DEPLAN study. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Bibi, S.; Contreras-Hernández, J.; Vaqué-Crusellas, C. Pakistani Women: Promoting Agents of Healthy Eating Habits in Catalonia-Protocol of a Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Randomized Control Trial (RCT) Based on the Transtheoretical Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DAWN News. Pakistan Has World’s Third Highest Number of Diabetics. 2021. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1650860/pakistan-has-worlds-third-highest-number-of-diabetics (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- ABC7 New York. Park Ridge Hospital’s Video Series Dispels Myths to Reduce South Asian Community’s Heart Disease Risk. 2020. Available online: https://abc7chicago.com/south-asian-cardiovascular-center-heart-disease-risk-park-ridge/5874482/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Diabetes UK. South Asian Living and Diabetes | Community Champions | Diabetes UK. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1qUzgVxzIQ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Public Health Agency of Catalonia. Petits Canvis per Menjar Millor. 2018. Available online: https://canalsalut.gencat.cat/ca/vida-saludable/alimentacio/petits-canvis-per-menjar-millor/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Benefits of Healthy Eating. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/resources-publications/benefits-of-healthy-eating.html (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- AdvocateHealthCare. What South Asians should Know about Carbs in Their Diet. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=94FfDQ-r4Wo&list=PL5R_Kf4cF6TjEl466Ll_w4qOgsmuFzyTP&index=26 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- AdvocateHealthCare. Why Should South Asians Eat More Protein? 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7UWpjRQSfe0&list=PL5R_Kf4cF6TjEl466Ll_w4qOgsmuFzyTP&index=3 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Public Health Agency of Catalonia. La Priàmide de L’alimentació Saludable. 2015. Available online: https://salutpublica.gencat.cat/ca/ambits/promocio_salut/alimentacio_saludable/la-piramide-de-lalimentacio-saludable (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Ministry of Panning, Development and Reform, Government of Pakistan. Pakistan Dietary Guidelines for Better Nutrition. 2019. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.pk/uploads/report/Pakistan_Dietary_Nutrition_2019.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Harvard TH Chan. School of Public Health. Healthy Eating Plate. 2011. Available online: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-eating-plate/ (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Receta Cubana. Cómo Hacer CREMA DE CALABAZA Casera. 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S5E2F42BXd8 (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Healthy Fusion. Healthy Protein Salad—Weight Loss Friendly by Healthy Food Fusion. 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_5AMBk5zD-w (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Public Health Agency of Catalonia. Aliments Frescos i de Temporada. Available online: https://opcions.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/calendari_Alimentsfrescos-web.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Fisioterapia Querétaro. Rutina de Entrenamiento en SILLA para ADULTOS MAYORES. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67wl05H1K3U&t=631s (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Urine Colour Chart. 2022. Available online: https://www.southtees.nhs.uk/content/uploads/2022/08/Urine-colour-chart.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Lawrence, M.; Costa Louzada, M.L.; Pereira Machado, P. Ultra-Processed Foods, Diet Quality, and Health Using the NOVA Classification System; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN). Información Alimentaria Facilitada al Consumidor. 2015. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/web/seguridad_alimentaria/detalle/etiquetado_informacion_alimentaria.htm (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Kandula, N.R.; Dave, S.; De Chavez, P.J.; Bharucha, H.; Patel, Y.; Seguil, P.; Kumar, S.; Baker, D.W.; Spring, B.; Siddique, J. Translating a heart disease lifestyle intervention into the community: The South Asian Heart Lifestyle Intervention (SAHELI) study; a randomized control trial. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stage of Change | Objective | Process of Change | Session |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-contemplation | Raise awareness of the problem by stimulating the possibility of change | Consciousness raising | 1. Why us? The most common health problems of the Pakistani population |

| Dramatic relief | |||

| Self-reevaluation | 2. Food myths and beliefs: What does science say? | ||

| Contemplation | Decant the scale towards change | Consciousness raising | 3. What is a healthy diet? |

| Self-reevaluation | |||

| Self-reevaluation | 4. The value of our traditional diet | ||

| Environmental reevaluation | |||

| Preparation | Reinforce knowledge to facilitate the change | Consciousness raising | 5. Small changes to eat better (MORE) |

| Counterconditioning | |||

| Self-liberation | 6. Small changes to eat better (CHANGE) | ||

| Counterconditioning | |||

| Self-liberation | 7. Small changes to eat better (LESS) | ||

| Counterconditioning | |||

| Action | Effectuate the change by promoting self-efficiency | Counterconditioning | 8. Let’s plan our weekly food purchase! |

| Stimulus or environmental control | |||

| Counterconditioning | 9. How to plan a balanced menu? | ||

| Stimulus or environmental control | |||

| Maintenance | Maintain the change | Helping relationships | 10. Photovoice |

| Social liberation | Acquisition of the role of promoting agent of healthy eating habits for the rest of the community. |

| Sessions | Final Material | Dietician’s Observations | Participants’ Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Why us? The most common health problems of the Pakistani population | A brief habit change sheet in Urdu and Catalan where participants could write down the lifestyle changes that they want to achieve. Type of material: Own elaboration. | The PowerPoint presentation helped raise awareness among the participants. They were surprised by the exposed data and felt identified with the people from the videos. Through the habit change sheet, they were able to reflect and record the healthy changes they wanted to incorporate into their lifestyle. | Participants were satisfied with the material of the session. They appreciated the Urdu translation of it. The videos of SA people who improved their health by incorporating small changes in their lifestyle were highly appreciated by the participants. |

| 2. Food myths and beliefs: What does science say? | An infographic in Urdu and Catalan that contained an explanation based on scientific evidence regarding all the discussed myths and beliefs. Type of material: Own elaboration. | The infographic allowed to discuss and demystify the myths and beliefs in an orderly way. The part of the infographic that highlighted the dietary aspects for the different stages of women’s lives particularly captured their interest. | Participants liked the infographic about myths and beliefs finding it visual, complete, and easy to understand. They found the content of the infographic very appropriate, which demonstrated the scientific explanation of their beliefs without disparaging or judging them. |

| 3. What is a healthy diet? | A visual booklet of serving size and frequency of different food groups translated into Urdu and Catalan. Type of material: Adapted from the existing material | The PowerPoint permitted to explain the concept of macro and micronutrients in a simple and efficient way. The designed activities facilitated the interaction between participants and allowed us to evaluate the acquisition of the content. | Participants appreciated the use of Pakistani food for the explanation of the concept of portion size and frequency of consumption. They found the designed activities very simple and effective to revise the content worked during the session. They considered the booklet very visual and convenient for everyday use. |

| 4. The value of our traditional Pakistani diet | A visual booklet in Urdu and Catalan with the explanation of the healthy plate’s structure along with 18 examples of different healthy plates elaborated with Pakistani food. Type of material: Adapted from the existed material | The Urdu translation of Harvard’s Healthy Eating Plate and its application to the Pakistani diet allowed the participants to perfectly understand its structure. Through the projected material participants were able to recall the positive aspects of the traditional Pakistani diet. | Participants easily comprehended the structure of the healthy plate, finding it simple, practical and suitable for them. They appreciated the presented examples of healthy plates finding them delicious, quick to prepare and adapted to their diet. They greatly appreciated the booklet of 18 healthy plates. |

| 5. Small changes to eat better (MORE) | A short recipe book in Urdu and Catalan with 18 simple and easy recipes of healthy snacks. The recipes are based on fruit, vegetables, legumes, and nuts. Type of material: Own elaboration. | The translation and cultural adoption allowed the participants to understand the recommendations of a local nutrition guide. The video recipes helped them to understand how they can put the proposed suggestions into practice. Through the guide recommendations and some video demonstrations, they were able to know about a large variety of exercises considering their age, strength and mobility. | Participants found the PowerPoint very visual, simple, and easy to understand. After understanding the guides’ recommendations, they agreed with them. The video recipes from Spanish and Pakistan food channels were highly appreciated. They found them easy to prepare and adapted to their taste. |

| 6. Small changes to eat better (CHANGE) | The PowerPoint presentation in Urdu and Catalan allowed proposing healthy changes in a simple and organised way. However, some participants seemed a little confused to locate the suggested grocery stores where they could buy different types of flour and fresh and local products. Through the activity of elaborating healthy snacks, participants learnt to make different Pakistan, Middle East, and Mediterranean snacks more healthily. | With the adapted PowerPoint presentation, participants were able to understand all the suggested changes in the nutrition guide. They found the healthy snacks activity very useful and entertaining which allowed them to put into practice the acquired knowledge during the previous session. They appreciated the recipe book finding it visual and practical. | |

| 7. Small changes to eat better (LESS) | A booklet in Catalan and Urdu with explanations and examples to analyse and interpret the food labels. The booklet also contains instructions to elaborate a list of daily or weekly food purchases. Type of material: Adapted from the existing material | The PowerPoint presentation of the session allowed us to discover and discuss all the doubts of the participants related to the consumption of red and processed meat. It also enabled us to explain the theoretical part related to the analysis and interpretation of food labels. | Participants were satisfied with the material of the session. They easily learnt the basic concepts to read and interpret the nutrition labels of the products and they were eager to analyse their favourite products. |

| 8. Let’s plan our weekly food purchase! | The theoretical-practical format of the session permitted the participants to put into practice the acquired concepts during the previous session. The booklet allowed them to revise the theoretical part of the analysis and interpretation of food labels. They also learnt how to access the web pages of local markets and analyse and buy different products. | Participants enjoyed the different activities of the session which allowed them to know about the purchasing of healthy options for all the food groups. Some women with a limited educational background found this session a little difficult to understand. | |

| 9. How to plan a balanced menu? | A booklet with 7 visual examples of daily healthy menus elaborated with healthy snacks (session 5–6) and healthy plates (session 4). Type of material: Own elaboration. | The adaption of the menus to the dietary pattern of participants facilitated the comprehension of the content. The visual examples of the daily menus were greatly appreciated by them. The material permitted them to learn to elaborate the personalised menu for themselves. | Participants appraised the worked material finding it very visual and easily comprehensible. They found the examples of menus realistic, practical, and easy to follow. They were grateful to have a printed booklet of visual examples of menus. |

| 10. PhotoVoice | A PowerPoint with 70 healthy plates elaborated by the participants. Type of material: Own elaboration. | The participants presented their plates confidently in different languages. Some of them were moved to tears while expressing the emotional significance related to the ingredients of their plates. The guests highly appreciated their efforts. | Participants appreciated each other’s work. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohamed-Bibi, S.; Vaqué-Crusellas, C.; Alonso-Pedrol, N. Design of Culturally and Linguistically Tailored Nutrition Education Materials to Promote Healthy Eating Habits among Pakistani Women Participating in the PakCat Program in Catalonia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5239. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245239

Mohamed-Bibi S, Vaqué-Crusellas C, Alonso-Pedrol N. Design of Culturally and Linguistically Tailored Nutrition Education Materials to Promote Healthy Eating Habits among Pakistani Women Participating in the PakCat Program in Catalonia. Nutrients. 2022; 14(24):5239. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245239

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohamed-Bibi, Saba, Cristina Vaqué-Crusellas, and Núria Alonso-Pedrol. 2022. "Design of Culturally and Linguistically Tailored Nutrition Education Materials to Promote Healthy Eating Habits among Pakistani Women Participating in the PakCat Program in Catalonia" Nutrients 14, no. 24: 5239. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245239

APA StyleMohamed-Bibi, S., Vaqué-Crusellas, C., & Alonso-Pedrol, N. (2022). Design of Culturally and Linguistically Tailored Nutrition Education Materials to Promote Healthy Eating Habits among Pakistani Women Participating in the PakCat Program in Catalonia. Nutrients, 14(24), 5239. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245239