Gut–Brain Interaction Disorders and Anorexia Nervosa: Psychopathological Asset, Disgust, and Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal Disturbances in AN

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

- female sex,

- patients undergoing a complete physical examination during the first in-person visit and further investigations when indicated for the exclusion of any organic disease.

- Section A—psychopathological asset: the clinical aspects of AN were assessed by means of EDI-3, body dysmorphism were measured by means of BUT-A, disgust was measured by means of DISGUST SCALE, and the anxiety–depressive axis, also related to social phobia, were measured by means of HADS and SPAS, respectively.

- Section B—upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed using a standardized questionnaire and the diagnoses of functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, functional constipation, and functional diarrhea were performed according to the ROME IV Criteria.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Section A—AN Patients Underwent the Following Questionnaires

- The Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3) [22,23] is a standardized and validated questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70) [24] for the clinical assessment of psychological constructs known to be clinically relevant to eating disorders. Its 91 items are organized into 12 subscales, i.e., 3 that are specific to eating disorders and 9 that are general psychological scales but also relevant to eating disorders. The 3 eating disorder risk scales are as follows: drive for thinness (DT; 7 items); bulimia (B; 8 items); and body dissatisfaction (BD; 10 items), which assess attitudes and behaviors regarding eating, weight, and body shape. The 9 psychological scales are as follows: low self-esteem (LSE; 6 items); personal alienation (PA; 7 items), interpersonal insecurity (II; 7 items); interpersonal alienation (IA; 7 items), interoceptive deficits (ID; 9 items); emotional dysregulation (ED; 8 items); perfectionism (P; 6 items); asceticism (A; 7 items); and fear of maturity (MF; 8 items), which analyze the psychological traits associated with the development and maintenance of eating disorders. The test also provides 6 composite scores, i.e., 1 specific and 5 related supplementary constructs: eating disorder risk index (EDRC); inadequacy (IC); interpersonal problems (IPC); affective problems (APC); hypercontrol (OC); and general psychological maladjustment (GPMC).

- The participants respond to the items on a 6-point Likert scale but are recoded as 0, 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 instead of 0, 0, 0, 1, 2, and 3. The scale is standardized and can be hand-scored or computer-scored. For our study, we used the hand-scored mode for the scoring clinical report [22]. It is specified that item 71 in the original version is not included in any scale and was therefore also not included in the analyses in the present study. The pathological clinical reference cut-off based on a total sample (N = 839) is ≥50.

- The Body Uneasiness Test (BUT) [25] is a questionnaire that explores body-image-related discomfort through various areas that cause body dissatisfaction, such as weight phobia, preoccupation, or avoidance and hypercontrol. It consists of 71 multiple-choice items on a six-point Likert-type scale (range: 0–5; from “never” to “always”) and is divided into two parts: BUT-A, consisting of 34 clinical items; and BUT-B, consisting of 37 items examining specific concerns about particular body parts or functions. For the purposes of the present study, BUT-A was used, whose clinical items provide a global severity index (GSI; the average rating of all 34 items constituting the BUT-A), which was used for statistical correlation. The other subscales were as follows: weight phobia (WP; 8 items); body image concerns (BIC; 9 items); avoidance (A; 6 items), compulsive self-monitoring (CSM; 5 items); and depersonalization (D; 6 items). Cronbach’s alpha values vary between 0.69 and 0.90. The clinical cut-off for body dysmorphism is a score ≥ 1.2.

- The Disgust Scale-Revised (DS-R) [26] is used to assess the perception of disgust. The scale investigates the levels of perception of the primary emotion of disgust through 27 items, each of which is rated on a 5-point scale (score 0–4) with regard to the extent to which participants find the experience from not disgusting at all to very disgusting. A total score for general disgust sensitivity can be calculated. The DS-R demonstrated a high degree of internal consistency and adequate convergent and discriminant validity [27]. The cut-off for disgust dispersion is a total score > 26.

- The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [28] is used for the assessment of the anxiety–depression axis. The test is divided into 2 components: the HADS-A consists of 7 items assessing anxiety symptoms while the HADS-D consists of 7 items assessing depressive symptoms. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3) providing a maximum of 21 points for each subscale. A cut-off score of ≥8 points was applied for each subscale as this value showed good sensitivity and specificity for determining the presence of anxiety or depressive symptoms, respectively. The HADS is part of the standardized and internationally validated scales as demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85.

- The Social Phobia Anxiety Scale (SPAS) [29] is used for the assessment of phobic symptomatology related to social anxiety. It is a standardized test that assesses the presence of anxiety associated with social phobia. It comprises 12 questions assessed on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The positively worded items (items 1, 2, 5, 8, and 11) are rated in reverse before summing. The total scores range from 12 to 60. A higher score indicates greater anxiety about the considered aspect. The internal consistency of the SPAS was reported to be 0.90 and the test–retest reliability at 8 weeks was 0.82 [30]. The clinical symptomatologic cut-off is a score of ≥20.

2.2.2. Section B—AN Patients Underwent the Following Questionnaires

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Section A—Psychopathological Asset of AN

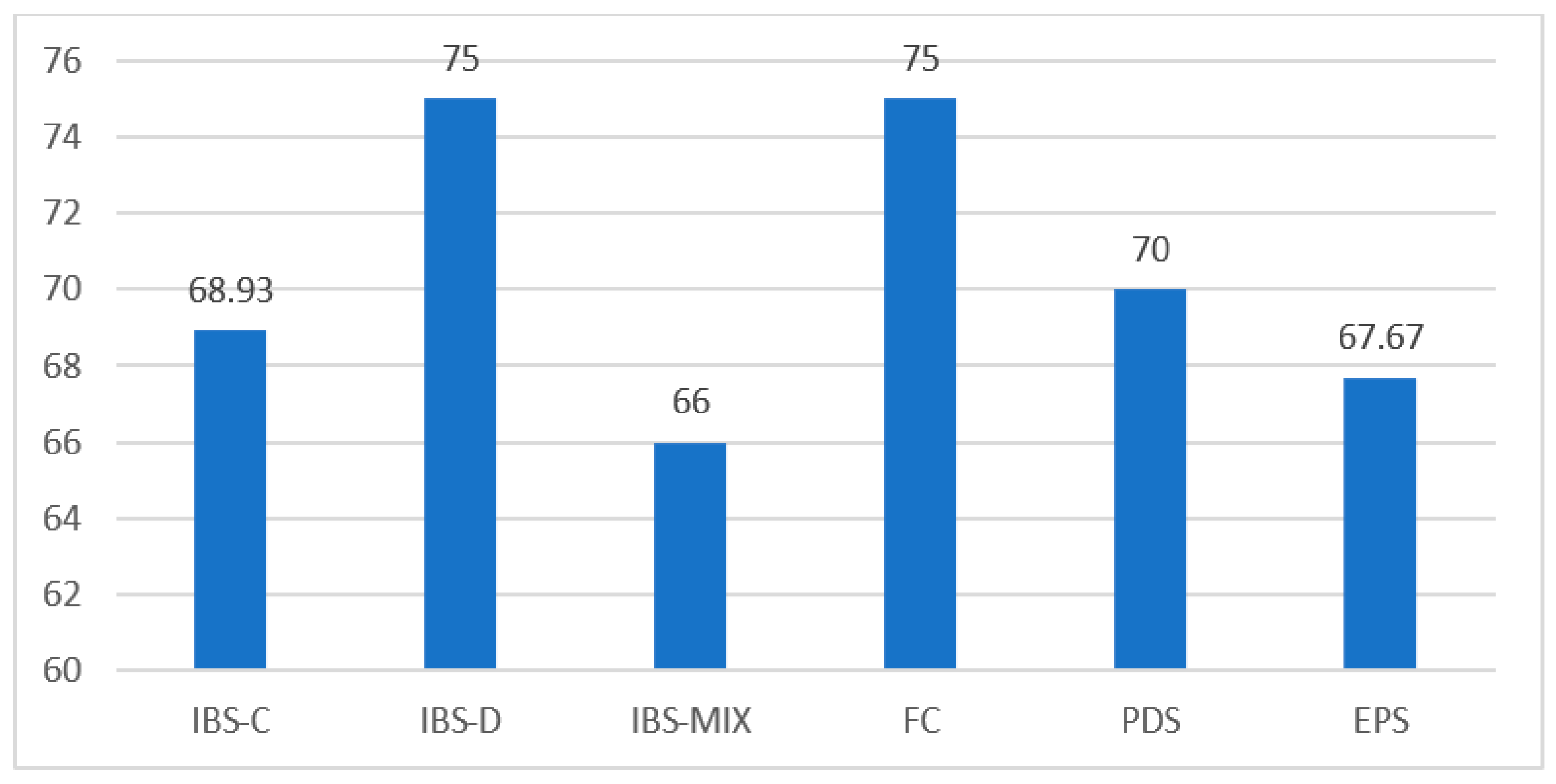

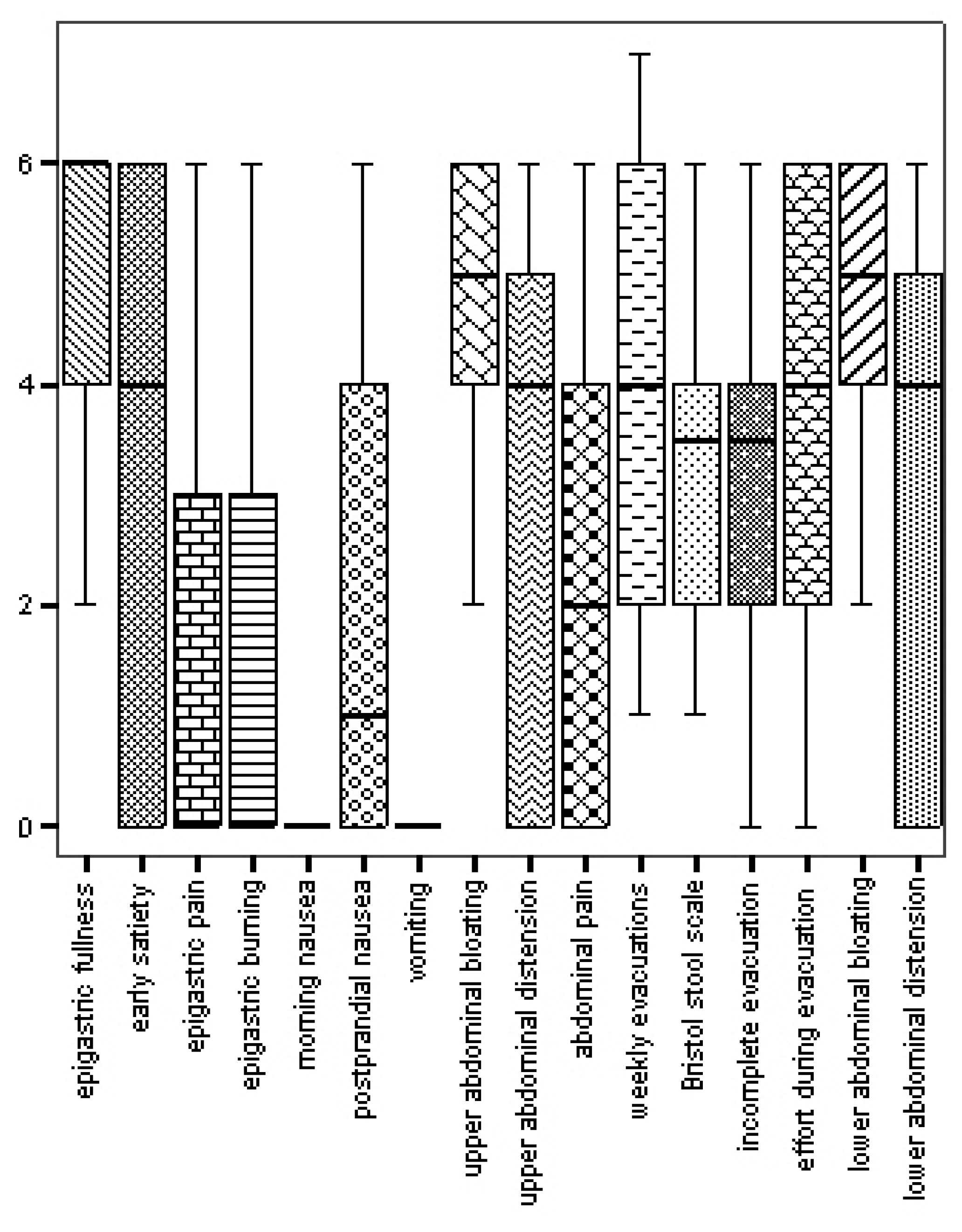

3.3. Section B—Gastroenterological Features

3.4. Relationship between the Psychopathological Asset and DGBI Diagnosis

3.4.1. EDI-3

3.4.2. BUT

3.4.3. DISGUST

3.4.4. HADS

3.4.5. SPAS

3.5. Correlation of Psychological Asset and the Intensity–Frequency of Each Symptom Score

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santomauro, D.F.; Melen, S.; Mitchison, D.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.; Ferrari, A.J. The hidden burden of eating disorders: An ex-tension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Eeden, A.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Prevalence and Correlates of DSM-5–Defined Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F.R.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silén, Y.; Sipilä, P.N.; Raevuori, A.; Mustelin, L.; Marttunen, M.; Kaprio, J.; Keski-Rahkonen, A. DSM-5 eating disorders among adolescents and young adults in Finland: A public health concern. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F.R.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Donker, G.A.; Susser, E.S.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; Hoek, H.W. Three decades of eating disorders in Dutch primary care: Decreasing incidence of bulimia nervosa but not of anorexia nervosa. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bern, E.M.; Woods, E.R.; Rodriguez, L. Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Eating Disorders. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 63, e77–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetterich, L.; Mack, I.; Giel, K.E.; Zipfel, S.; Stengel, A. An update on gastrointestinal disturbances in eating disorders. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2019, 497, 110318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonicola, A.; Gagliardi, M.; Guarino, M.P.L.; Siniscalchi, M.; Ciacci, C.; Iovino, P. Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedlinger, C.; Schmidt, G.; Weiland, A.; Stengel, A.; Giel, K.E.; Zipfel, S.; Enck, P.; Mack, I. Which symptoms, complaints and com-plications of the gastrointestinal tract occur in patients with eating disorders? A systematic review and quantitative analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman, D.A. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1262–1279.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanel, V.; Schalla, M.A.; Stengel, A. Irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia in patients with eating disorders—A systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2021, 29, 692–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperber, A.D.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Drossman, D.A.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Simren, M.; Tack, J.; Whitehead, W.E.; Dumitrascu, D.L.; Fang, X.; Fukudo, S.; et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 99–114.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, C.; Abraham, S.; Kellow, J. Psychological features are important predictors of functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients with eating disorders. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 40, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Luscombe, G.M.; Boyd, C.; Kellow, J.; Abraham, S. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in eating disorder patients: Altered distribution and predictors using ROME III compared to ROME II criteria. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 16293–16299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbara, G.; Cremon, C.; Bellini, M.; Corsetti, M.; Di Nardo, G.; Falangone, F.; Fuccio, L.; Galeazzi, F.; Iovino, P.; Sarnelli, G.; et al. Italian guidelines for the management of irritable bowel syndrome: Joint Consensus from the Italian Societies of: Gastroenter-ology and Endoscopy (SIGE), Neurogastroenterology and Motility (SINGEM), Hospital Gastroenterologists and Endoscopists (AIGO), Digestive Endoscopy (SIED), General Medicine (SIMG), Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Pediatric Nutrition (SI-GENP) and Pediatrics (SIP). Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinelli, L.; Bucci, C.; Santonicola, A.; Zingone, F.; Ciacci, C.; Iovino, P. Anhedonia in irritable bowel syndrome and in inflammatory bowel diseases and its relationship with abdominal pain. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 31, e13531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonicola, A.; Siniscalchi, M.; Capone, P.; Gallotta, S.; Ciacci, C.; Iovino, P. Prevalence of functional dyspepsia and its subgroups in patients with eating disorders. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 4379–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, C.A.; Rania, M.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Thornton, L.M.; Bulik, C.M. Evaluating disorders of gut-brain interaction in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rome Foundation: ROME IV Diagnostic Criteria for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI). Available online: https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/ (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Garner, D.M. Eating Disorder Inventory-3; Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.: Lutz, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, M.; Pannocchia, L.; Dalle Grave, R.; Muratori, F.; Viglione, V. Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3); Italian Adaptation; Manual; Giunti O.S.: Florence, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, L.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Friborg, O.; Rokkedal, K. Validating the Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3): A Comparison Between 561 Female Eating Disorders Patients and 878 Females from the General Population. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2011, 33, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzzolaro, M.; Vetrone, G.; Marano, G.; Garfinkel, P. The Body Uneasiness Test (BUT): Development and validation of a new body image assessment scale. Eat. Weight Disord. 2006, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidt, J.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P. Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1994, 16, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro, M.; Ruggi, S.; Caravita, S.C.S.; Gatti, M.; Colombo, L.; Gilli, G.M. A Measure to Assess Individual Differences for Disgust Sensitivity: An Italian Version of the Disgust Scale—Revised. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, E.A.; Leary, M.R.; Rejeski, W.J. Tie Measurement of Social Physique Anxiety. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1989, 11, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Fung, S.F. Social Physique Anxiety Scale: Psychometric Evaluation and Development of a Chinese Adaptation. Int. J. En-viron. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, G.; Limongelli, P.; Pascariello, A.; Rossetti, G.; Del Genio, G.; Del Genio, A.; Iovino, P. Association between persistent symptoms and long-term quality of life after laparoscopic total fundoplication. Am. J. Surg. 2008, 196, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, G.; Ruggiero, L.; D’antonio, E.; Gagliardi, M.; Nunziata, R.; Di Sarno, A.; Abbatiello, C.; Di Feo, E.; De Vivo, S.; Santonicola, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on symptoms in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders: Relationship with anxiety and perceived stress. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, B.M.R.; Bolus, R.; Agarwal, N.; Sayuk, G.; Harris, L.A.; Lucak, S.; Esrailian, E.; Chey, W.D.; Lembo, A.; Karsan, H.; et al. Measuring symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome: Development of a framework for clinical trials. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 32, 1275–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, N.J.; Walker, M.M.; Holtmann, G. Functional dyspepsia. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 32, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, L.; Conte, E.; Ambrosecchia, M.; Janiri, D.; Di Pietro, S.; De Martin, V.; Di Nicola, M.; Rinaldi, L.; Sani, G.; Gallese, V.; et al. Anomalous self-experience, body image disturbance, and eating disorder symptomatology in first-onset anorexia nervosa. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 27, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncrieff-Boyd, J.; Byrne, S.; Nunn, K. Disgust and Anorexia Nervosa: Confusion between self and non-self. Adv. Eat. Disord. 2014, 2, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, E.; Grzegorzewski, P.; Kostecka, B.; Kucharska, K. Self-disgust and disgust sensitivity are increased in anorexia nervosa inpatients, but only self-disgust mediates between comorbid and core psychopathology. Eur. Eat Disord. Rev. 2021, 29, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicario, C.M.; Rafal, R.D.; di Pellegrino, G.; Lucifora, C.; Salehinejad, M.A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Avenanti, A. Indignation for moral violations suppresses the tongue motor cortex: Preliminary TMS evidence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2022, 17, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, C.; de Jong, P.J.; Renken, R.J.; Georgiadis, J.R. Disgust trait modulates frontal-posterior coupling as a function of disgust domain. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapps, N.; van Oudenhove, L.; Enck, P.; Aziz, Q. Brain imaging of visceral functions in healthy volunteers and IBS patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 64, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicker, B.; Keysers, C.; Plailly, J.; Royet, J.-P.; Gallese, V.; Rizzolatti, G. Both of Us Disgusted in My Insula: The Common Neural Basis of Seeing and Feeling Disgust. Neuron 2003, 40, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, L.Q.; Nomi, J.S.; Hébert-Seropian, B.; Ghaziri, J.; Boucher, O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 34, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicario, C.M.; Rafal, R.D.; Martino, D.; Avenanti, A. Core, social and moral disgust are bounded: A review on behavioral and neural bases of repugnance in clinical disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troop, N.; Baker, A. Food, Body, and Soul: The Role of Disgust in Eating Disorders; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Alizadeh-Tabari, S.; Zamani, V. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoe, D.J.; Han, A.; Anderson, A.; Katzman, D.K.; Patten, S.B.; Soumbasis, A.; Flanagan, J.; Paslakis, G.; Vyver, E.; Marcoux, G.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | N (%) | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | 19.32 | 5.59 | |

| BMI | - | 17.63 | 2.23 | |

| Marital status | Single | 33 (86.8) | - | - |

| Cohabiting/Married | 2 (5.3) | - | - | |

| Engaged | 3 (7.9) | - | - | |

| Smoke | Yes | 5 (13.2) | - | - |

| No | 33 (86.8) | - | - | |

| Alcohol | Yes | 1 (2.6) | - | - |

| No | 37 (97.4) | - | - | |

| Coffee | Yes | 13 (34.2) | - | - |

| No | 25 (65.8) | - | - | |

| Surgical intervention | Yes | 1 (2.7) | - | - |

| No | 37 (97.3) | - | - | |

| Pharmacotherapy | PPI | 4 (10.5) | - | - |

| Supplements | 17 (44.7) | - | - | |

| * EDI-3 subscales (cut-off ≥ 50) | Mean | SD | Min.–Max. |

| EDI-DT | 20.24 | 7.64 | 3–28 |

| EDI-B | 7.50 | 7.04 | 0–29 |

| EDI-BD | 22.92 | 7.53 | 9–36 |

| EDI-LSE | 14.71 | 5.83 | 3–24 |

| EDI-PA | 13.76 | 6.38 | 1–27 |

| EDI-II | 16.50 | 6.34 | 4–28 |

| EDI-IA | 12.97 | 5.40 | 4–24 |

| EDI-ID | 21.92 | 7.45 | 4–36 |

| EDI-ED | 12.97 | 6.76 | 3–28 |

| EDI-P | 9.21 | 4.88 | 0–20 |

| EDI-A | 13.18 | 6.07 | 4–28 |

| EDI-MF | 17.58 | 7.20 | 3–32 |

| EDI-IC | 28.47 | 11.44 | 4–51 |

| EDI-IPC | 29.47 | 10.80 | 10–50 |

| EDI-APC | 34.89 | 11.92 | 8–60 |

| EDI-OC | 22.39 | 9.31 | 4–48 |

| GPMC | 132.82 | 38.34 | 70–231 |

| EDRC | 50.66 | 18.39 | 16–93 |

| ** BUT subscales (cut-off ≥ 1.2) | Mean | SD | Min.–Max. |

| BUT-GSI | 3.10 | 0.84 | 1.29–4.91 |

| BUT-WP | 3.62 | 1.04 | 1.25–5 |

| BUT-BIC | 3.25 | 1.02 | 0.89–5 |

| BUT-A | 2.39 | 1.06 | 0.17–4.67 |

| BUT-CSM | 2.58 | 0.90 | 0.67–4.17 |

| BUT-D | 3.47 | 1.28 | 1.20–6 |

| DISGUST Scale (cut-off > 26) | Mean | SD | Min.–Max. |

| 69.26 | 13.12 | 36–89 | |

| HADS (cut-off ≥ 8) | Mean | SD | Min.–Max. |

| ANXIETY (A) | 12.87 | 3.48 | 6–17 |

| DEPRESSION (D) | 7.95 | 3.14 | 4–16 |

| SPAS (cut-off ≥20) | Mean | SD | Min.-Max. |

| 48.79 | 7.92 | 34–60 |

| Functional Dyspepsia (FD) | % |

| PDS | 88.8 |

| EPS | 41.6 |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) | % |

| IBS-C | 75 |

| IBS-D | 5 |

| IBS-MIX | 20 |

| IBS-U | 0 |

| IBS-C | IBS-D | IBS-MIX | FC | PDS | EPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUT-GSI | 3.04 ± 0.93 | 3.15 ± 0 | 2.98 ± 0.84 | 2.92 ± 0.82 | 3.24 ± 0.78 | 2.94 ± 0.78 |

| BUT-WP | 3.49 ± 1.13 | 3.50 ± 0 | 3.43 ± 1.25 | 3.71 ± 1.25 | 3.74 ± 0.96 | 3.22 ± 1.11 |

| BUT-BIC | 3.02 ± 1.10 | 3.33 ± 0 | 3.19 ± 1.02 | 3.29 ± 1.22 | 3.38 ± 0.98 | 3.11 ± 0.92 |

| BUT-A | 2.62 ± 1.18 | 1.83 ± 0 | 2.04 ± 0.41 | 1.94 ± 1.33 | 2.56 ± 1.02 | 2.22 ± 0.99 |

| BUT-CSM | 2.51 ± 0.95 | 3.17 ± 0 | 2.66 ± 0.82 | 2.16 ± 0.43 | 2.77 ± 0.81 | 2.45 ± 0.76 |

| BUT-D | 3.53 ± 1.51 | 3.80 ± 0 | 3.40 ± 0.99 | 3.06 ± 1.02 | 3.59 ± 1.30 | 3.64 ± 1.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carpinelli, L.; Savarese, G.; Pascale, B.; Milano, W.D.; Iovino, P. Gut–Brain Interaction Disorders and Anorexia Nervosa: Psychopathological Asset, Disgust, and Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112501

Carpinelli L, Savarese G, Pascale B, Milano WD, Iovino P. Gut–Brain Interaction Disorders and Anorexia Nervosa: Psychopathological Asset, Disgust, and Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Nutrients. 2023; 15(11):2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112501

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarpinelli, Luna, Giulia Savarese, Biagio Pascale, Walter Donato Milano, and Paola Iovino. 2023. "Gut–Brain Interaction Disorders and Anorexia Nervosa: Psychopathological Asset, Disgust, and Gastrointestinal Symptoms" Nutrients 15, no. 11: 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112501

APA StyleCarpinelli, L., Savarese, G., Pascale, B., Milano, W. D., & Iovino, P. (2023). Gut–Brain Interaction Disorders and Anorexia Nervosa: Psychopathological Asset, Disgust, and Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Nutrients, 15(11), 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112501