Impact of the Family Environment on the Frequency of Animal-Based Product Consumption in School-Aged Children in Central Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Survey Instrument

2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. The Frequency of Meat and Meat Product Consumption

3.2. The Frequency of Fish Consumption

3.3. The Frequency of Egg Consumption

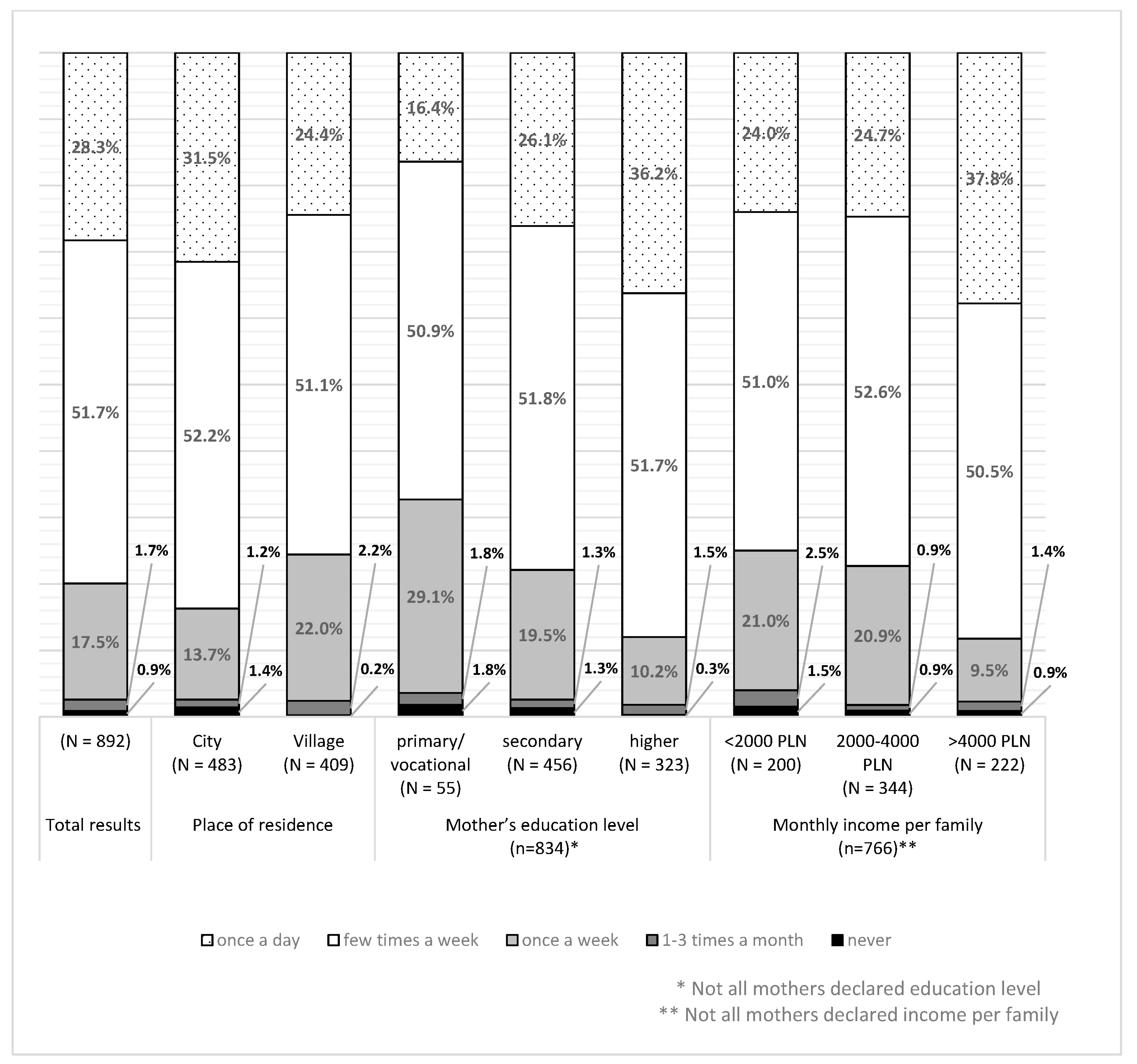

3.4. The Frequency of Dairy Product Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bohrer, B.M. Review: Nutrient density and nutritional value of meat products and non-meat foods high in protein. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, L. The benefits of animal products for child nutrition in developing countries. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2018, 37, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudinskaya, E.C.; Naspetti, S.; Arsenos, G.; Caramelle-Holtz, E.; Latvala, T.; Martin-Collado, D.; Orsini, S.; Ozturk, E.; Zanoli, R. European Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Red Meat Labelling Attributes. Animals 2021, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvard, V.; Loomis, D.; Guyton, K.Z.; Grosse, Y.; El Ghissassi, F.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Mattock, H.; Straif, K. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1599–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—Poland. Available online: http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/Poland/en (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Maguire, E.R.; Monsivais, P. Socio-economic dietary inequalities in UK adults: An updated picture of key food groups and nutrients from national surveillance data. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, S.; Neter, J.; Brouwer, I.; Huisman, M.; Visser, M. Misperception of self-reported adherence to the fruit, vegetable and fish guidelines in older Dutch adults. Appetite 2014, 82, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.; Feucht, Y. How to increase demand for carp? Consumer attitudes and preferences in Germany and Poland. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3267–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, S.A.; Branum, A.M. Dietary intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids and fish among US children 12-60 months of age. Matern. Child Nutr. 2015, 11, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magriplis, E.; Mitsopoulou, A.-V.; Karageorgou, D.; Bakogianni, I.; Dimakopoulos, I.; Micha, R.; Michas, G.; Chourdakis, M.; Chrousos, G.; Roma, E.; et al. Frequency and Quantity of Egg Intake Is Not Associated with Dyslipidemia: The Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey (HNNHS). Nutrients 2019, 11, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekajło-Kozłowska, A.; Różańska, D.; Zatońska, K.; Szuba, A.; Regulska-Ilow, B. Association between egg consumption and elevated fasting glucose prevalence in relation to dietary patterns in selected group of Polish adults. Nutr. J. 2019, 18, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKune, S.L.; Stark, H.; Sapp, A.C.; Yang, Y.; Slanzi, C.M.; Moore, E.V.; Omer, A.; N’diaye, A.W. Behavior Change, Egg Consumption, and Child Nutrition: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020007930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, Y.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd. Egg Consumption in Infants is Associated with Longer Recumbent Length and Greater Intake of Several Nutrients Essential in Growth and Development. Nutrients 2018, 10, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, Y.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd. Egg Consumption in U.S. Children is Associated with Greater Daily Nutrient Intakes, including Protein, Lutein + Zeaxanthin, Choline, α-Linolenic Acid, and Docosahexanoic Acid. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardas, M.; Grochowska-Niedworok, E.; Całyniuk, B.; Kolasa, I.; Grajek, M.; Bielaszka, A.; Kiciak, A.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M. Consumption of milk and milk products in the population of the Upper Silesian agglomeration inhabitants. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 28976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtyła-Buciora, P.; Stawińska-Witoszyńska, B.; Klimberg, A.; Wojtyła, A.; Goździewska, M.; Wojtyła, K.; Piątek, J.; Wojtyła, C.; Sygit, M.; Ignyś, I.; et al. Nutrition-related health behaviours and prevalence of overweight and obesity among Polish children and adolescents. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2013, 20, 332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, G.; Adan, R.A.H.; Belot, M.; Brunstrom, J.M.; De Graaf, K.; Dickson, S.L.; Hare, T.; Maier, S.; Menzies, J.; Preissl, H.; et al. The determinants of food choice. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predanocyová, K.; Kubicová, L.; Kádeková, Z.; Košičiarová, I. Key factors affecting consumption of meat and meat products from perspective of Slovak consumers. Potravin. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2019, 13, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicka, E.; Kaczorowska, J.; Rejman, K.; Szczebyło, A. Parental Food Choices and Engagement in Raising Children’s Awareness of Sustainable Behaviors in Urban Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadka, K.; Pałkowska-Goździk, E.; Rosołowska-Huszcz, D. Relation between Environmental Factors and Children’s Health Behaviors Contributing to the Occurrence of Diet-Related Diseases in Central Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gawecki, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Czarnocinska, J.; Galinski, G.; Kollajtis-Dolowy, A.; Roszkowski, W.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Przybylowicz, K.; Krusinska, B.; et al. Dietary Habits and Nutrition Beliefs Questionnaire for People 15–65 Years Old, Version 1.1—Interviewer Administered Questionnaire. In Dietary Habits and Nutrition Beliefs Questionnaire and the Manual for Developing of Nutritional Data; Gawecki, J., Ed.; The Committee of Human Nutrition, Polish Academy of Sciences: Olsztyn, Poland, 2017; Chapter 1; ISBN 9788395033001. [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt, J.; Olsen, A. Meat Reduction in 5 to 8 Years Old Children—A Survey to Investigate the Role of Parental Meat Attachment. Foods 2021, 10, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjit, N.; Wilkinson, A.V.; Lytle, L.M.; Evans, A.E.; Saxton, D.; Hoelscher, D.M. Socioeconomic inequalities in children’s diet: The role of the home food environment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12 (Suppl. S1), S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmett, P.M.; Jones, L.R. Diet, growth, and obesity development throughout childhood in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73 (Suppl. S3), 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.M.; Jaacks, L.M.; Batis, C.; Vanderlee, L.; Taillie, L.S. Patterns of Red and Processed Meat Consumption across North America: A Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Comparison of Dietary Recalls from Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, U.B.; Johansen, M.N.; Joensen, A.M.; Lau, C.; Overvad, K.; Larsen, M.L. Educational level and living arrangements are associated with dietary intake of red meat and fruit/vegetables: A Danish cross-sectional study. Scand. J. Public Health 2019, 47, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.; Corsello, G.; Quattrocchi, E.; Dell’Aquila, L.; Ehrich, J.; Giardino, I.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M. Caring for Infants and Children Following Alternative Dietary Patterns. J. Pediatr. 2017, 187, 339–340.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexy, U.; Fischer, M.; Weder, S.; Längler, A.; Michalsen, A.; Sputtek, A.; Keller, M. Nutrient Intake and Status of German Children and Adolescents Consuming Vegetarian, Vegan or Omnivore Diets: Results of the VeChi Youth Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiler, T.M.; Egloff, B. Examining the “Veggie” personality: Results from a representative German sample. Appetite 2018, 120, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, V.L.; Jones, L.R.; Rogers, I.S.; Ness, A.R.; Emmett, P.M. Is maternal education level associated with diet in 10-year-old children? Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2037–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.O.; Kerver, J.M. Nutritional Contribution of Eggs to American Diets. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000, 19 (Suppl. S5), 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öğütcü, M.; Elmas, E.T. Assessment of Consumer Preferences and Perceptions on Egg Consumption via Correspondence Analysis. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2020, 17, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ansem, W.J.; Schrijvers, C.T.; Rodenburg, G.; van de Mheen, D. Maternal educational level and children’s healthy eating behaviour: Role of the home food environment (cross-sectional results from the INPACT study). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finger, J.D.; Varnaccia, G.; Tylleskär, T.; Lampert, T.; Mensink, G.B.M. Dietary behaviour and parental socioeconomic position among adolescents: The German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents 2003–2006 (KiGGS). BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Martínez, M.I.; Alegre-Martínez, A.; Cauli, O. Omega-3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Intake in Children: The Role of Family-Related Social Determinants. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, S.; Muresan, I.; Correia, D.; Severo, M.; Lopes, C. The role of socio-economic factors in food consumption of Portuguese children and adolescents: Results from the National Food, Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2015–2016. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, M.F.; Günlü, A.; Can, H.Y. Fish consumption preferences and factors influencing it. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 35, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Lawi, M.U.S.; Kusnandar, K.; Nuhriawangsa, A.M.P. The frequent of fish intake can increase the chance of Child intelligence of aged 9-10 years in Surakarta. Bali Med. J. 2019, 8, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymandera-Buszka, K.; Górecka, D. Częstotliwość spożycia wybranych napojów mlecznych. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol. 2009, 42, 688–692. [Google Scholar]

- Całyniuk, B.; Złoteńka-Synowiec, M.; Grochowska-Niedworok, E.; Misiarz, M.; Malczyk, E.; Filarska, M.; Kutnohorská, J. Częstotoliwość spożycia mleka I produktów młecznych przez mlodziez w wieku 16–18 lat. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2015, 196, 240–244. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Navarro, J.C.; Oki, A.M.; Antoniazzi, L.; Bonfim, M.A.C.; Hong, V.; De Almeida Gaspar, M.C.; Sandrim, V.C.; Nogueira, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; et al. Consumption of animal-based and processed food associated with cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical atherosclerosis biomarkers in men. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2019, 65, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, A.M.; Flood, V.L.; Denyer, G.; Ayer, J.G.; Webb, K.L.; Marks, G.B.; Celermajer, D.S.; Gill, T.P. The effect of dairy consumption on blood pressure in mid-childhood: CAPS cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Environmental Factors | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | City | 483 | 54.1 |

| Village | 409 | 45.9 | |

| Mother’s education level | Basic and vocational education | 55 | 6.2 |

| Secondary education | 456 | 51.1 | |

| Higher education | 323 | 36.2 | |

| Not declared | 58 | 6.5 | |

| Mother’s body mass (according to BMI) | Underweight | 34 | 3.8 |

| Normal body mass | 542 | 60.8 | |

| Overweight | 183 | 20.5 | |

| Obese | 45 | 5.0 | |

| Not declared | 88 | 9.9 | |

| Net income per family * | <2000 PLN | 200 | 22.4 |

| 2000–4000 PLN | 344 | 38.6 | |

| >4000 PLN | 222 | 24.9 | |

| not declared | 126 | 14.1 | |

| Number of children in the family | 1 | 196 | 22.0 |

| 2 | 471 | 52.8 | |

| 3 | 156 | 17.5 | |

| 4+ | 69 | 7.7 | |

| Types of Meat | % of Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Chicken | 96 | 4 |

| Turkey | 24 | 76 |

| Pork | 69 | 31 |

| Beef | 14 | 86 |

| Others | 3 | 97 |

| Types of Meat Products | % of responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Ham | 82 | 18 |

| Sausage | 42 | 58 |

| Hotdog | 58 | 42 |

| Pate | 22 | 78 |

| Homemade | 10 | 90 |

| Others | 1 | 99 |

| Foods | Meat | Fish | Eggs | Diary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | G = 0.284, p < 0.001 | G = 0.289, p < 0.001 | G = 0.203, p < 0.001 | G = 0.097, p < 0.05 |

| Grains | NS | G = 0.132, p < 0.01 | G = 0.204, p < 0.001 | G = 0.174, p < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pałkowska-Goździk, E.; Zadka, K.; Rosołowska-Huszcz, D. Impact of the Family Environment on the Frequency of Animal-Based Product Consumption in School-Aged Children in Central Poland. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122781

Pałkowska-Goździk E, Zadka K, Rosołowska-Huszcz D. Impact of the Family Environment on the Frequency of Animal-Based Product Consumption in School-Aged Children in Central Poland. Nutrients. 2023; 15(12):2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122781

Chicago/Turabian StylePałkowska-Goździk, Ewelina, Katarzyna Zadka, and Danuta Rosołowska-Huszcz. 2023. "Impact of the Family Environment on the Frequency of Animal-Based Product Consumption in School-Aged Children in Central Poland" Nutrients 15, no. 12: 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122781

APA StylePałkowska-Goździk, E., Zadka, K., & Rosołowska-Huszcz, D. (2023). Impact of the Family Environment on the Frequency of Animal-Based Product Consumption in School-Aged Children in Central Poland. Nutrients, 15(12), 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122781