Association between Diet Quality and Stroke among Chinese Adults: Results from China Health and Nutrition Survey 2011

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

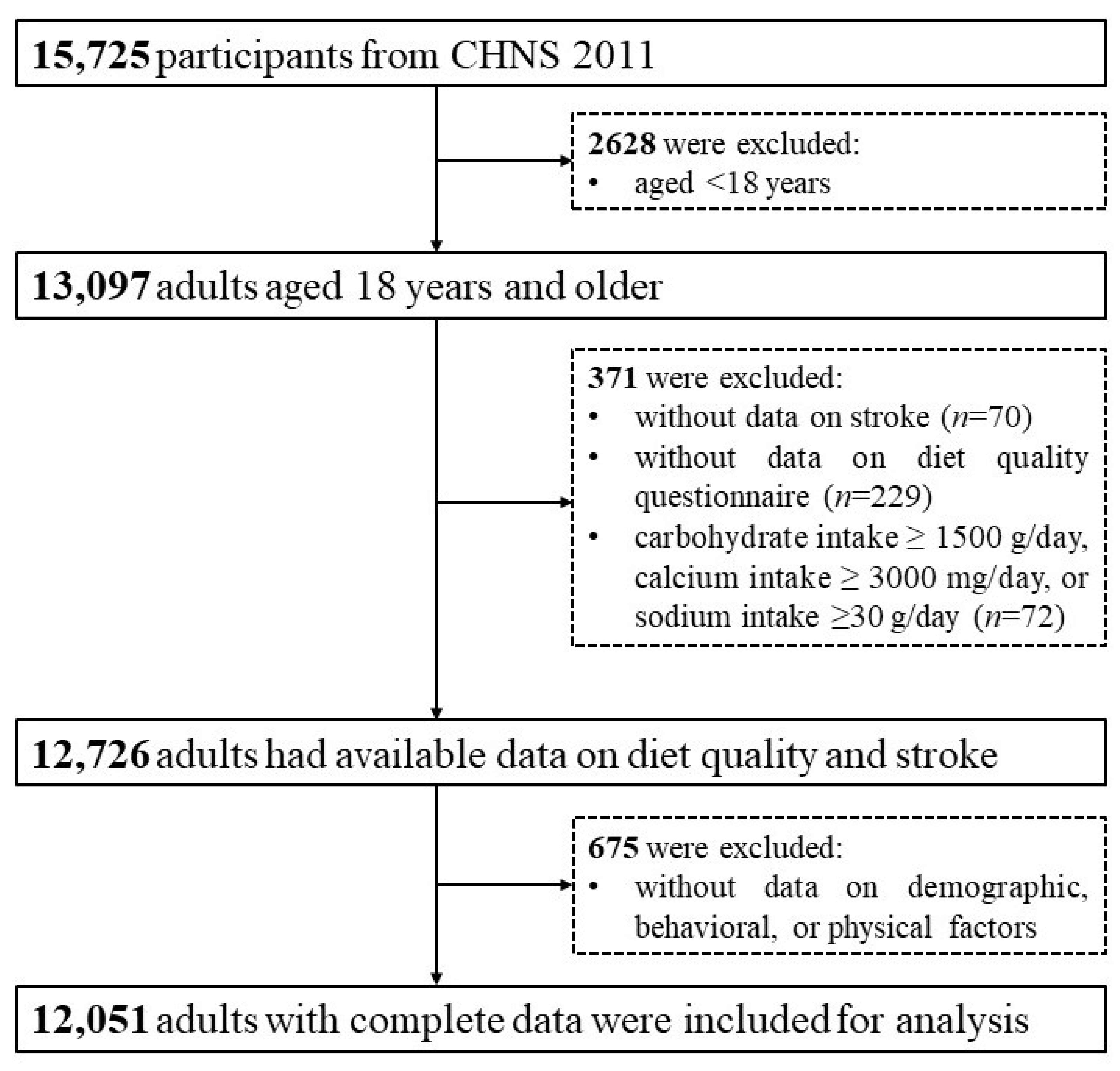

2.1. Data Resources and Study Participants

2.2. Stroke and Other Variables

2.3. Dietary Data Collection and Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Distribution of Diet Quality Scores and Stroke

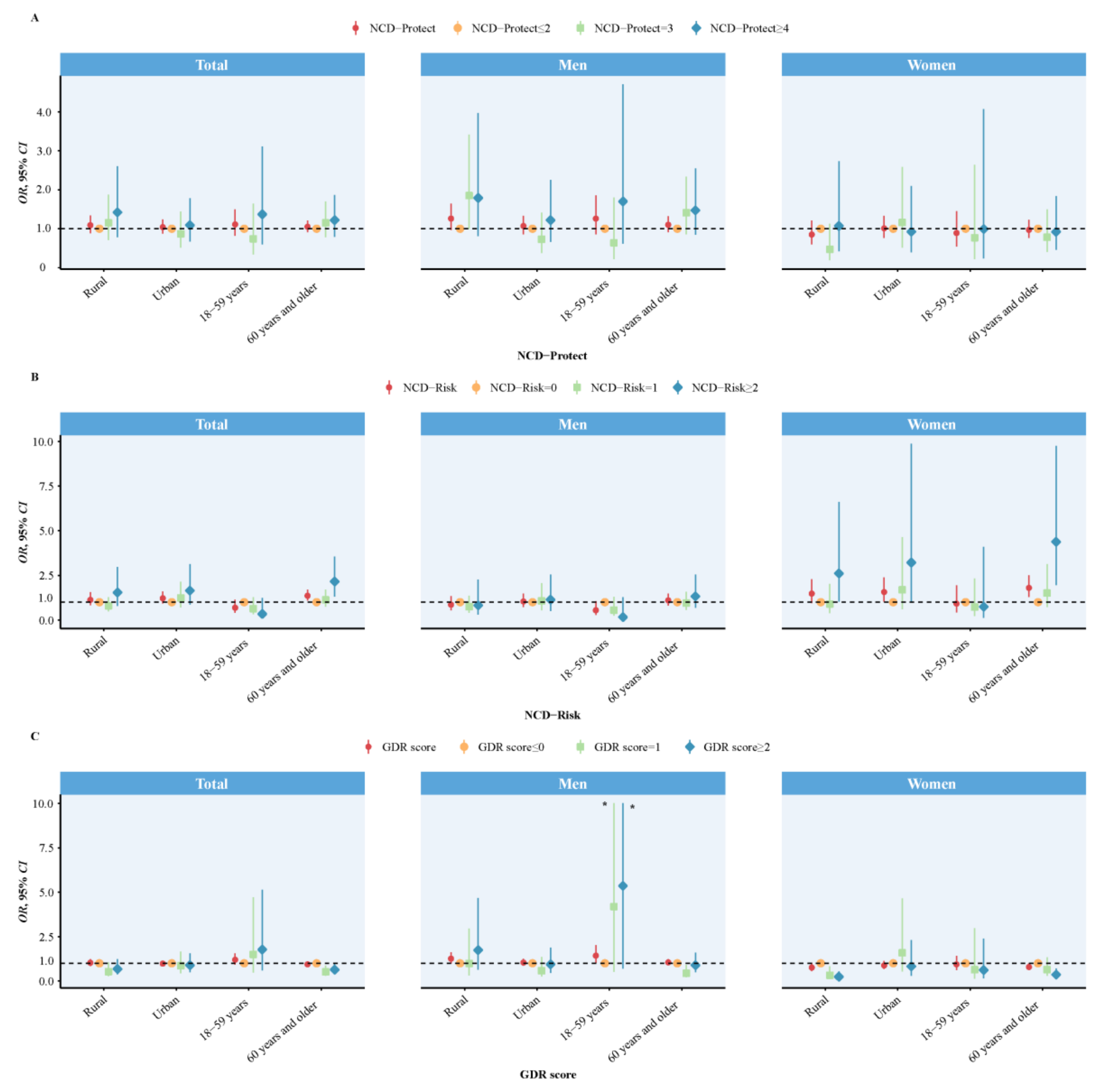

3.3. Associations of Diet Quality Scores with Stroke

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.; Thayabaranathan, T.; Donnan, G.A.; Howard, G.; Howard, V.J.; Rothwell, P.M.; Feigin, V.; Norrving, B.; Owolabi, M.; Pandian, J.; et al. Global stroke statistics 2019. Int. J. Stroke 2020, 15, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigin, V.L.; Norrving, B.; Mensah, G.A. Global burden of stroke. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The GBD 2016 Lifetime Risk of Stroke Collaborators. Global, Regional, and Country-Specific Lifetime Risks of Stroke, 1990 and 2016. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2429–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, M.J.; Bushnell, C.D.; Howard, G.; Gargano, J.W.; Duncan, P.W.; Lynch, G.; Khatiwoda, A.; Lisabeth, L. Sex differences in stroke: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, medical care, and outcomes. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petrea, R.E.; Beiser, A.S.; Seshadri, S.; Margarete, K.H.; Kase, C.S.; Wolf, P.A. Gender differences in stroke incidence and poststroke disability in the Framingham Heart Study. Stroke 2009, 40, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, Q.; Li, R.; Wang, L.; Yin, P.; Wang, Y.; Yan, C.; Qian, Z.; Vaughn, M.G.; McMillin, S.E.; Ren, Y.; et al. Temporal trend and attributable risk factors of stroke burden in China, 1990–2019: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2021, 12, e897–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackam, D.G.; Spence, J.D. Combining multiple approaches for the secondary prevention of vascular events after stroke: A quantitative modeling study. Stroke 2007, 38, 1881–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, J. Diet in Stroke: Beyond Antiplatelets and Statins. J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2019, 10, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernan, W.N.; Ovbiagele, B.; Black, H.R.; Bravata, D.M.; Chimowitz, M.I.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Fang, M.C.; Fisher, M.; Furie, K.L.; Heck, F.V.; et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014, 45, 2160–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.T.; Corra, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice: The sixth joint task force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2315–2381. [Google Scholar]

- Guzik, A.; Bushnell, C. Stroke Epidemiology and Risk Factor Management. Continuum 2017, 23, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Toledo, E.; Arós, F.; Fiol, M.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Covas, M.I.; Fernández-Crehuet, J.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Extravirgin olive oil consumption reduces risk of atrial fibrillation: The PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) trial. Circulation 2014, 130, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joshipura, K.J.; Ascherio, A.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rimm, E.B.; Speizer, F.E.; Hennekens, C.H.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C. Fruit and vegetable intake in relation to risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA 1999, 282, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chowdhury, R.; Stevens, S.; Gorman, D.; Pan, A.; Warnakula, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Ward, H.; Johnson, L.; Crowe, F.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Association between fish consumption, long chain omega 3 fatty acids, and risk of cerebrovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012, 345, e6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, N.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Mu, C.; Han, C.; Zhu, R.; Liu, X. Role of diet in stroke incidence: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective observational studies. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzullo, P.; D’Elia, L.; Kandala, N.B.; Cappuccio, F.P. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2009, 339, b4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DQQ Indicator Guide 2023. Available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1RGwNititbYqSrGpUXhQs7mHWgLIgOxAlN5N0AOZN3qc/edit (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Global Diet Quality Project. Available online: https://www.dietquality.org/indicators (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Ma, S.; Herforth, A.W.; Vogliano, C.; Zou, Z. Most Commonly-Consumed Food Items by Food Group, and by Province, in China: Implications for Diet Quality Monitoring. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Du, S.F.; Zhai, F.Y.; Zhang, B. Cohort Profile: The China Health and Nutrition Survey—Monitoring and understand_x0002_ing socio-economic and health change in China, 1989–2011. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 39, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Zhai, F.Y.; Du, S.F.; Popkin, B.M. The China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1989–2011. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15 (Suppl. 1), 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry; Report of a WHO Expert Committee; World Health Organization Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- WS/T 428-2013; Criteria of Weight for Adults; National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Ma, S.; Yang, L.; Zhao, M.; Magnussen, C.G.; Xi, B. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control rates among Chinese adults, 1991–2015. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, F.Y.; Du, S.F.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.G.; Du, W.W.; Popkin, B.M. Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991–2011. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15 (Suppl. S1), 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yan, S.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Du, S.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Adair, L.; Popkin, B. The expanding burden of cardiometabolic risk in China: The China Health and Nutrition Survey. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Herforth, A.W.; Xi, B.; Zou, Z. Validation of the Diet Quality Questionnaire in Chinese Children and Adolescents and Relationship with Pediatric Overweight and Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, T.E.; Howard, V.J.; Jiménez, M.; Rexrode, K.M.; Acelajado, M.C.; Kleindorfer, D.; Chaturvedi, S. Impact of Conventional Stroke Risk Factors on Stroke in Women: An Update. Stroke 2018, 49, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexrode, K.M.; Madsen, T.E.; Yu, A.Y.X.; Carcel, C.; Lichtman, J.H.; Miller, E.C. The Impact of Sex and Gender on Stroke. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpani, V.; Baena, C.P.; Jaspers, L.; van Dijk, G.M.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Dhana, K.; Tielemans, M.J.; Voortman, T.; Freak-Poli, R.; Veloso, G.G.V.; et al. Lifestyle factors, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Kamensky, V.; Manson, J.E.; Silver, B.; Rapp, S.R.; Haring, B.; Beresford, S.A.A.; Snetselaar, L.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S. Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Stroke, Coronary Heart Disease, and All-Cause Mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative. Stroke 2019, 50, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.D. Diet for stroke prevention. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2018, 13, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spence, J.D. Nutrition and Risk of Stroke. Nutrients 2019, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demel, S.L.; Kittner, S.; Ley, S.H.; McDermott, M.; Rexrode, K.M. Stroke Risk Factors Unique to Women. Stroke 2018, 49, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, C.; McCullough, L.D.; Awad, I.A.; Chireau, M.V.; Fedder, W.N.; Furie, K.L.; Howard, V.J.; Lichtman, J.H.; Lisabeth, L.D.; Piña, I.L.; et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Women: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014, 45, 1545–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Linderman, G.C.; Wu, C.; Cheng, X.; Mu, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: Data from 17 million adults in a population-based screening study (China PEACE Million Persons Project). Lancet 2017, 390, 2549–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Batis, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Popkin, B.M. Understanding the patterns and trends of sodium intake, potassium intake, and sodium to potassium ratio and their effect on hypertension in China. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update PROJECT Expert Report 2018. Recommendations and Public Health and Policy Implications. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Recommendations.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. Healthy Diet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Román, G.C.; Jackson, R.E.; Gadhia, R.; Román, A.N.; Reis, J. Mediterranean diet: The role of long-chain ω-3 fatty acids in fish; polyphenols in fruits, vegetables, cereals, coffee, tea, cacao and wine; probiotics and vitamins in prevention of stroke, age-related cognitive decline, and Alzheimer disease. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 175, 724–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, B.P. Cardiovascular Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet Are Driven by Stroke Reduction and Possibly by Decreased Atrial Fibrillation Incidence. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillum, R.F.; Mussolino, M.E.; Madans, J.H. The relationship between fish consumption and stroke incidence. The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey). Arch. Intern. Med. 1996, 156, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Kuller, L.H.; Burke, G.L.; Tracy, R.P.; Siscovick, D.S. Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiac benefits of fish consumption may depend on the type of fish meal consumed: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 2003, 107, 1372–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.; Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Rangarajan, S.; Zhang, X.; Swaminathan, S.; Dagenais, G.; Gupta, R.; Mohan, V.; Lear, S.; et al. Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators. Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017, 390, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Your Guide to Lowering Blood Pressure; INH Publication: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2003; pp. 1–20. Available online: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/dash/new_dash.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Feng, Q.; Fan, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, R.; Liu, M.; Song, Y. Adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet and risk of stroke: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Medicine 2018, 97, e12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flight, I.; Clifton, P. Cereal grains and legumes in the prevention of coronary heart disease and stroke: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keli, S.O.; Hertog, M.G.L.; Feskens, E.J.; Kromhout, D. Dietary flavonoids, antioxidant vitamins, and incidence of stroke: The Zutphen study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1996, 156, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arts, I.C.; Hollman, P.C. Polyphenols and disease risk in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81 (Suppl. 1), 317S–325S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molla, W.; Adem, D.A.; Tilahun, R.; Shumye, S.; Kabthymer, R.H.; Kebede, D.; Mengistu, N.; Ayele, G.M.; Assefa, D.G. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children (6–23 months) in Gedeo zone, Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, A.S.; Mozaffarian, D.; Roger, V.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Berry, J.D.; Borden, W.B.; Bravata, D.M.; Dai, S.; Ford, E.S.; Fox, C.S.; et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 127, e841. [Google Scholar]

- Leening, M.J.; Ferket, B.S.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Kavousi, M.; Deckers, J.W.; Nieboer, D.; Heeringa, J.; Portegies, M.L.; Hofman, A.; Ikram, M.A.; et al. Sex Differences in Lifetime Risk and First Manifestation of Cardiovascular Disease: Prospective Population Based Cohort Study. BMJ 2014, 349, g5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vyas, M.V.; Silver, F.L.; Austin, P.C.; Yu, A.Y.X.; Pequeno, P.; Fang, J.; Laupacis, A.; Kapral, M.K. Stroke Incidence by Sex across the Lifespan. Stroke 2021, 52, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, S.; Caplan, L.R.; James, M.L. Sex Differences in Incidence, Pathophysiology, and Outcome of Primary Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2015, 46, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | Total (n = 12,051) | Men (n = 5628) | Women (n = 6423) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), years | 51.00 (21.00) | 52.00 (20.00) | 51.00 (21.00) | 0.076 |

| 18–59 years, n (%) | 8528 (70.77) | 3944 (70.08) | 4584 (71.37) | 0.120 |

| 60 years and older, n (%) | 3523 (29.23) | 1684 (29.92) | 1839 (28.63) | - |

| Residence, n (%) | 0.793 | |||

| Rural | 6916 (57.39) | 3237 (57.52) | 3679 (57.28) | |

| Urban | 5135 (42.61) | 2391 (42.48) | 2744 (42.72) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Unmarried | 659 (5.47) | 388 (6.89) | 271 (4.22) | |

| Married | 10,191 (84.57) | 4893 (86.94) | 5298 (82.48) | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 1201 (9.97) | 347 (6.17) | 854 (13.30) | |

| Educational levels, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Primary school and lower | 4344 (36.05) | 1625 (28.87) | 2719 (42.33) | |

| Middle school and higher | 7707 (63.95) | 4003 (71.13) | 3704 (57.67) | |

| Behavioral/physical factors | ||||

| Smoking status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Never smoked | 8373 (69.48) | 2170 (38.56) | 6203 (96.57) | |

| Smokes | 3678 (30.52) | 3458 (61.44) | 220 (3.43) | |

| Drinking status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Never drank | 8019 (66.54) | 2309 (41.03) | 5710 (88.90) | |

| Drinks | 4032 (33.46) | 3319 (58.97) | 713 (11.10) | |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 23.94 (4.64) | 24.01 (4.76) | 23.87 (4.53) | 0.102 |

| Overweight/obesity, n (%) | 5394 (44.76) | 2590 (46.02) | 2804 (43.66) | 0.001 |

| WC, mean (SD), cm | 83.93 (11.11) | 86.05 (10.84) | 82.07 (11.01) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal obesity, n (%) | 4519 (37.54) | 2062 (36.66) | 2457 (38.32) | 0.060 |

| SBP, mean (SD), mmHg | 124.60 (17.8) | 126.36 (16.45) | 123.06 (18.77) | <0.001 |

| DBP, mean (SD), mmHg | 79.32 (10.71) | 80.93 (10.51) | 77.91 (10.69) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 3496 (29.01) | 1774 (31.52) | 1722 (26.81) | <0.001 |

| Dietary factors | ||||

| GDR score, median (IQR) | 2.00 (2.00) | 2.00 (1.00) | 2.00 (2.00) | <0.001 |

| Total energy, median (IQR), kcal/day | 1814.07 (944.09) | 2007.45 (1018.42) | 1676.19 (821.58) | <0.001 |

| Carbohydrate, median (IQR), g/day | 253.31 (158.33) | 275.92 (174.09) | 236.38 (141.85) | <0.001 |

| Protein, median (IQR), g/day | 62.42 (37.80) | 68.67 (39.86) | 57.55 (34.48) | <0.001 |

| Fat, median (IQR), g/day | 58.23 (51.03) | 63.03 (53.79) | 53.43 (48.10) | <0.001 |

| Calcium, median (IQR), mg/day | 360.88 (300.84) | 382.18 (314.09) | 342.69 (287.21) | <0.001 |

| Sodium, median (IQR), mg/day | 3725.38 (2569.57) | 4002.53 (2738.79) | 3523.83 (2354.39) | <0.001 |

| Total | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total stroke cases | 192 (1.59) | 121 (2.15) | 71 (1.11) |

| NCD-Protect score | |||

| ≤2 | 85 (1.54) | 50 (1.87) | 35 (1.23) |

| 3 | 57 (1.46) | 38 (2.07) | 19 (0.92) |

| ≥4 | 50 (1.90) | 33 (2.95) | 17 (1.13) |

| NCD-Risk score | |||

| 0 | 56 (1.69) | 39 (2.68) | 17 (0.92) |

| 1 | 95 (1.43) | 62 (1.96) | 33 (0.95) |

| ≥2 | 41 (1.95) | 20 (1.99) | 21 (1.91) |

| GDR score | |||

| ≤0 | 33 (1.90) | 17 (1.92) | 16 (1.87) |

| 1 | 46 (1.38) | 24 (1.48) | 22 (1.29) |

| ≥2 | 113 (1.62) | 80 (2.57) | 33 (0.85) |

| Diet Quality Scores | Total | Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| NCD-Protect score | ||||||

| Continuous | 1.06 (0.93–1.20) | 0.411 | 1.13 (0.95–1.33) | 0.159 | 0.95 (0.77–1.18) | 0.644 |

| Categories | ||||||

| ≤2 | 1.00 (reference) | - | 1.00 (reference) | - | 1.00 (reference) | - |

| 3 | 1.01 (0.71–1.43) | 0.957 | 1.18 (0.75–1.83) | 0.476 | 0.75 (0.42–1.34) | 0.337 |

| ≥4 | 1.21 (0.83–1.76) | 0.332 | 1.44 (0.89–2.33) | 0.140 | 0.91 (0.49–1.68) | 0.758 |

| NCD-Risk score | ||||||

| Continuous | 1.17 (0.95–1.43) | 0.132 | 0.96 (0.73–1.26) | 0.760 | 1.52 (1.13–2.06) | 0.006 |

| Categories | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 (reference) | - | 1.00 (reference) | - | 1.00 (reference) | - |

| 1 | 0.97 (0.68–1.37) | 0.848 | 0.87 (0.56–1.33) | 0.513 | 1.17 (0.64–2.15) | 0.616 |

| ≥2 | 1.47 (0.94–2.29) | 0.089 | 0.95 (0.53–1.73) | 0.872 | 2.71 (1.35–5.43) | 0.005 |

| GDR score | ||||||

| Continuous | 0.99 (0.89–1.12) | 0.913 | 1.11 (0.96–1.29) | 0.164 | 0.83 (0.69–1.00) | 0.052 |

| Categories | ||||||

| ≤0 | 1.00 (reference) | - | 1.00 (reference) | - | 1.00 (reference) | - |

| 1 | 0.68 (0.42–1.08) | 0.101 | 0.69 (0.36–1.32) | 0.264 | 0.65 (0.33–1.28) | 0.215 |

| ≥2 | 0.78 (0.52–1.17) | 0.233 | 1.16 (0.67–2.01) | 0.604 | 0.42 (0.22–0.77) | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Zou, Z. Association between Diet Quality and Stroke among Chinese Adults: Results from China Health and Nutrition Survey 2011. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143229

Gao D, Wang H, Wang Y, Ma S, Zou Z. Association between Diet Quality and Stroke among Chinese Adults: Results from China Health and Nutrition Survey 2011. Nutrients. 2023; 15(14):3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143229

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Disi, Huan Wang, Yue Wang, Sheng Ma, and Zhiyong Zou. 2023. "Association between Diet Quality and Stroke among Chinese Adults: Results from China Health and Nutrition Survey 2011" Nutrients 15, no. 14: 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143229

APA StyleGao, D., Wang, H., Wang, Y., Ma, S., & Zou, Z. (2023). Association between Diet Quality and Stroke among Chinese Adults: Results from China Health and Nutrition Survey 2011. Nutrients, 15(14), 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143229