A Systematic Review of Marketing Practices Used in Online Grocery Shopping: Implications for WIC Online Ordering

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Online Retail Environment

3. WIC Program Background & Policy Context

4. Online Marketing Considerations for WIC Participants

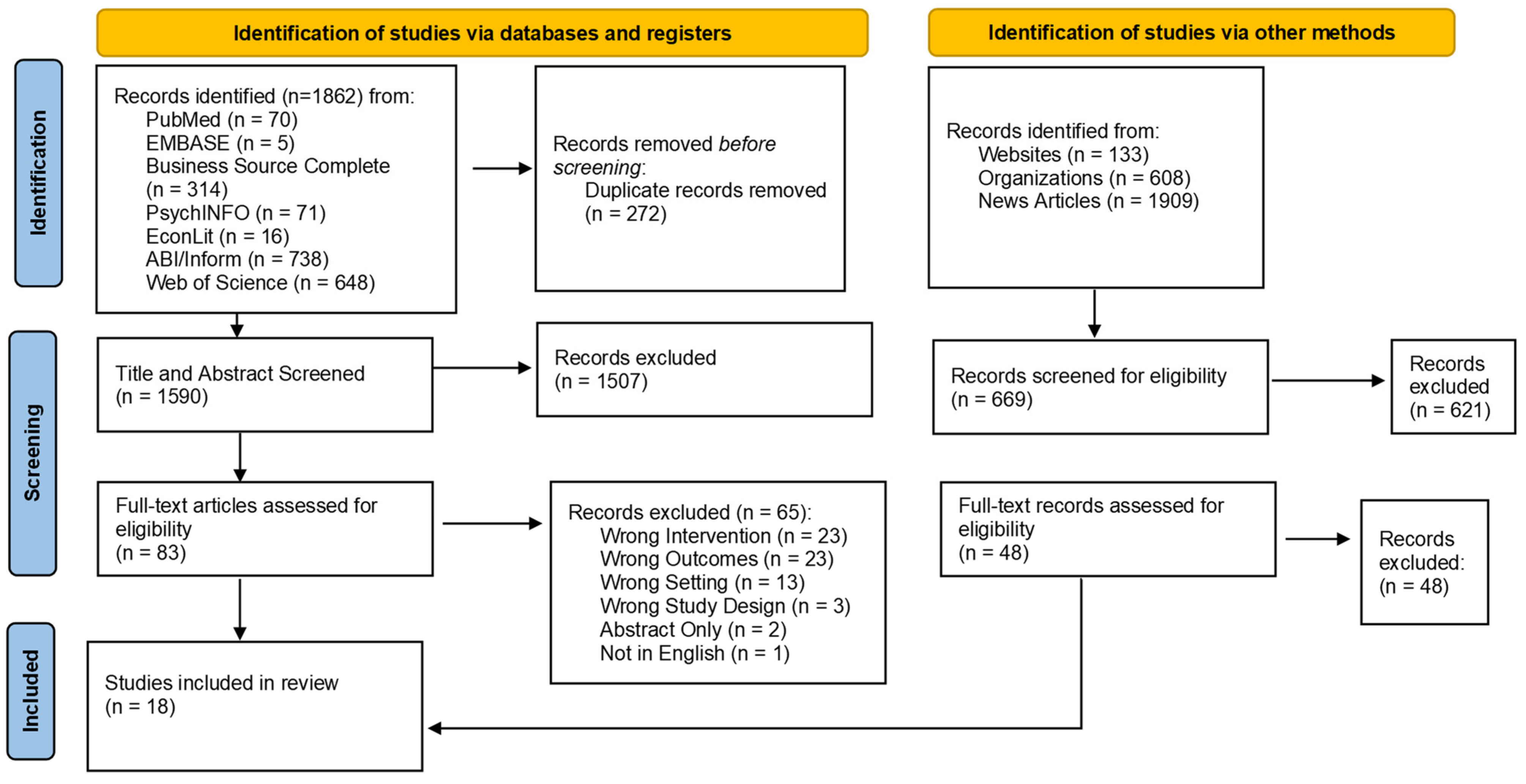

5. Materials & Methods

5.1. Data Sources

5.2. Search Strategy

5.3. Eligibility Criteria

5.4. Data Extraction

5.5. Evidence Synthesis

6. Results

6.1. Study Characteristics

6.2. Interventions and Outcomes

6.3. Price

6.4. Product

6.5. Placement

6.6. Promotions

7. Discussion

Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Systematic Review Search Strategies

Appendix B. Grey Literature Search Strategies

| Search Date | Database/Website | Web site (Search Strategies) | Results | Result Screened | new potentially relevant records | Total records | |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture—USDA.gov | 1 | site: usda.gov (marketing, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, online, advertising) | 87 | 87 | 15 | 15 | |

| 2 | site: usda.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 73 | 73 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: usda.gov (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 77 | 77 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: usda.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: usda.gov (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper, parent) | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Commerce.gov | 1 | site: commerce.gov (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 17 | 17 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | site: commerce.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: commerce.gov (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: commerce.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: usda.gov (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Federal Trade Commission—ftc.gov | 1 | site: ftc.gov (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 77 | 77 | 2 | 2 | |

| 2 | site: ftc.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 22 | 22 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: ftc.gov (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 21 | 21 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: ftc.gov(consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: ftc.gov (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | ||

| U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration—fda.gov | 1 | site: fda.gov (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 67 | 67 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | site: fda.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: fda.gov (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: fda.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: fda.gov (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—consumerfinance.gov | 1 | site: consumerfinance.gov (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 18 | 18 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | site: consumerfinance.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: consumerfinance.gov (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: consumerfinance.gov (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: consumerfinance.gov (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| WARC.com | 1 | site: WARC.com (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 41 | 41 | 3 | 3 | |

| 2 | site: WARC.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: WARC.com (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: WARC.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: WARC.com (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Kroger Precision Marketing | 1 | site: Krogerprecisionmarketing.com (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | site: Krogerprecisionmarketing.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: Krogerprecisionmarketing.com (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: Krogerprecisionmarketing.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: Krogerprecisionmarketing.com (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 8451.com | 1 | site: 8451.com (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | site: 8451.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: 8451.com (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: 8451.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: 8451.com (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| https://www.8451.com/knowledge-hub/insights-and-activation | 1 | site: 8451.com/knowledge-hub/insights-and-activation (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | site: 8451.com/knowledge-hub/insights-and-activation (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: 8451.com/knowledge-hub/insights-and-activation (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: 8451.com/knowledge-hub/insights-and-activation (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: 8451.com/knowledge-hub/insights-and-activation (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Walmart Marketing—https://walmartconnect.com | 1 | site: walmartconnect.com (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | site: walmartconnect.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: walmartconnect.com (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: walmartconnect.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: walmartconnect.com (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Advertising Research Foundation—https://thearf.org | 1 | site: thearf.org (marketing, Online shopping, grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising) | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | site: thearf.org (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: thearf.org (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: thearf.org (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: thearf.org (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Center for Disease Detection (CDD)—cddmedical.com | 1 | site: democraticmedia.org (marketing, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, online, advertising) | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2 | |

| 2 | site: democraticmedia.org (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: democraticmedia.org (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: democraticmedia.org (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: democraticmedia.org (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Market Dive | 1 | site: marketingdive.com (marketing, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, online, advertising) | 105 | 100 | 7 | 7 | |

| 2 | site: marketingdive.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 19 | 19 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: marketingdive.com (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 36 | 36 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: marketingdive.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: marketingdive.com (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Progressive Grocer | 1 | site: progressivegrocer.com (marketing, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, online, advertising) | 100 | 100 | 12 | 12 | |

| 2 | site: progressivegrocer.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 198 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: progressivegrocer.com (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 93 | 93 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: progressivegrocer.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 93 | 93 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site: progressivegrocer.com (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 96 | 96 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mckinsey.com | 1 | site: mckinsey.com (marketing, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, online, advertising) | 403 | 100 | 7 | 7 | |

| 2 | site: mckinsey.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping) | 273 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | site: mckinsey.com (marketing, e-commerce, retail, internet, promotion, Online grocery shopping, consumer behavior, Purchase behavior, advertising, food retail, grocer) | 303 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | site: mckinsey.com (consumer behavior, consumer, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket) | 145 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | site:mckinsey.com (consumer behavior, online grocery shopping, retail, e-commerce, internet, marketing, advertising, promotion, purchase behavior, online, food shopping, supermarket, shopper) | 41 | 41 | 0 | 0 |

References

- Carlson, S.; Neuberger, Z. Wic Works: Addressing the Nutrition and Health Needs of Low-Income Families for More than Four Decades; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): About WIC. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 7, Section 246.12, Food Delivery Methods; U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2006.

- Herring, A. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Supports Online Ordering and Transactions in WIC. In EO Guidance Document #FNS-GD-2021-0117; U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, L.; Lee, D.; Sallack, L.; Chauvenet, C.; Machell, G.; Kim, L.; Song, L.; Whaley, S.E. Multi-State WIC Participant Satisfaction Survey: Learning from Program Adaptations during COVID; National WIC Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, A.J.; Headrick, G.; Perez, C.; Greatsinger, A.; Taillie, L.S.; Zatz, L.; Bleich, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Khandpur, N. Food marketing practices of major online grocery retailers in the United States, 2019–2020. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 2295–2310.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpyn, A.; McCallops, K.; Wolgast, H.; Glanz, K. Improving Consumption and Purchases of Healthier Foods in Retail Environments: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maganja, D.; Miller, M.; Trieu, K.; Scapin, T.; Cameron, A.; Wu, J.H.Y. Evidence Gaps in Assessments of the Healthiness of Online Supermarkets Highlight the Need for New Monitoring Tools: A Systematic Review. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2022, 24, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandpur, N.; Zatz, L.Y.; Bleich, S.N.; Taillie, L.S.; Orr, J.A.; Rimm, E.B.; Moran, A.J. Supermarkets in Cyberspace: A Conceptual Framework to Capture the Influence of Online Food Retail Environments on Consumer Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing, 13th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Semuels, A. Why People Still Don’t Buy Groceries Online. Atlantic. 2019. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/02/online-grocery-shopping-has-been-slow-catch/581911/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Jensen, K.L.; Yenerall, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, T.E. US Consumers’ Online Shopping Behaviors and Intentions During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trude, A.C.B.; Ali, S.H.; Lowery, C.M.; Vedovato, G.M.; Lloyd-Montgomery, J.M.; Hager, E.R.; Black, M.M. A click too far from fresh foods: A mixed methods comparison of online and in-store grocery behaviors among low-income households. Appetite 2022, 175, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatz, L.Y.; Moran, A.J.; Franckle, R.L.; Block, J.P.; Hou, T.; Blue, D.; Greene, J.C.; Gortmaker, S.; Bleich, S.N.; Polacsek, M.; et al. Comparing shopper characteristics by online grocery ordering use among households in low-income communities in Maine. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5127–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, E.W.; Lo, A.E.; Hall, M.G.; Taillie, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Prevalence and Demographic Correlates of Online Grocery Shopping: Results from a Nationally Representative Survey During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 3079–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trude, A.C.B.; Lowery, C.M.; Ali, S.H.; Vedovato, G.M. An equity-oriented systematic review of online grocery shopping among low-income populations: Implications for policy and research. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1294–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, E.J.; Silvestri, D.M.; Mande, J.R.; Holland, M.L.; Ross, J.S. Availability of Grocery Delivery to Food Deserts in States Participating in the Online Purchase Pilot. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1916444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, I.S.; Liu, S.Y.; Hoffs, C.T.; LeBoa, C.; Chen, A.S.; Rummo, P.E. Disparities in SNAP online grocery delivery and implementation: Lessons learned from California during the 2020-21 COVID pandemic. Health Place 2022, 76, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.; Tomaino Fraser, K.; Arnow, C.; Mulcahy, M.; Hille, C. Online Grocery Shopping by NYC Public Housing Residents Using Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Benefits: A Service Ecosystems Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Communications Commission. 2020 Broadband Deployment Report; Federal Communications Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Rogus, S.; Guthrie, J.F.; Niculescu, M.; Mancino, L. Online Grocery Shopping Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Among SNAP Participants. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, O.; Tagliaferro, B.; Rodriguez, N.; Athens, J.; Abrams, C.; Elbel, B. EBT Payment for Online Grocery Orders: A Mixed-Methods Study to Understand Its Uptake among SNAP Recipients and the Barriers to and Motivators for Its Use. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 396–402.e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, M.C.; Beaird, J.; Steeves, E.T.A. WIC Participants’ Perspectives About Online Ordering and Technology in the WIC Program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 53, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huyghe, E.; Verstraeten, J.; Geuens, M.; Van Kerckhove, A. Clicks as a Healthy Alternative to Bricks: How Online Grocery Shopping Reduces Vice Purchases. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatz, L.Y.; Moran, A.J.; Franckle, R.L.; Block, J.P.; Hou, T.; Blue, D.; Greene, J.C.; Gortmaker, S.; Bleich, S.N.; Polacsek, M.; et al. Comparing Online and In-Store Grocery Purchases. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.W.; Toossi, S.; Hodges, L. The Food and Nutrition Assistance Landscape: Fiscal Year 2021 Annual Report; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Program Data, WIC Program, National Level Annual Summary, FY 1974–2021; U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine (NASEM). Review of WIC Food Packages: Improving Balance and Choice: Final Report; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. WIC EBT Activities. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-ebt-activities (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. WIC and Retail Grocery Stores [Fact Sheet]; U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Ver Ploeg, M.; Mancino, L.; Todd, J.E.; Clay, D.M.; Scharadin, B. Where Do Americans Usually Shop for Food and How Do They Travel to Get There? Initial Findings from the National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey; Economic Research Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Simon, E.; Leib, E.B. Mississippi WIC for the 21st Century; Harvard Law School Health Law and Policy Clinic: Cambridge, MA, USA; Harvard Law School Mississippi Delta Project: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saphores, J.-D.; Xu, L. E-shopping changes and the state of E-grocery shopping in the US—Evidence from national travel and time use surveys. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 87, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Report on the WIC Task Force on Supplemental Foods Delivery; U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Gretchen Swanson Center for Nutrition. WIC Online Ordering Grant. Available online: https://www.centerfornutrition.org/wic-online-ordering (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Zhang, Q.; Park, K.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C. The Online Ordering Behaviors among Participants in the Oklahoma Women, Infants, and Children Program: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.C.; Beaird, J.; Steeves, E.A. WIC Participants’ Perspectives of Facilitators and Barriers to Shopping With eWIC Compared With Paper Vouchers. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. WIC Policy Memorandum #2014-3 Vendor Management: Incentive Items, Vendor Discounts and Coupons; United States Department of Agriculture: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2014.

- Gleason, S.; Wroblewska, K.; Trippe, C.; Kline, N.; Meyers Mathieu, K.; Breck, A.; Marr, J.; Bellows, D. WIC Food Cost-Containment Practices Study: Final Report; U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Chauvenet, C.; De Marco, M.; Barnes, C.; Ammerman, A.S. WIC Recipients in the Retail Environment: A Qualitative Study Assessing Customer Experience and Satisfaction. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 416–424.e412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, D.; Thomsen, M.R.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Novotny, A.M. WIC Participation and Relative Quality of Household Food Purchases: Evidence from FoodAPS. South. Econ. J. 2019, 86, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Obando, D.A.; Jaime, P.C.; Parra, D.C. Sociodemographic factors associated with the consumption of ultra-processed foods in Colombia. Rev. Saude Publica 2020, 54, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arce-Urriza, M.; Cebollada, J.; Tarira, M.F. The effect of price promotions on consumer shopping behavior across online and offline channels: Differences between frequent and non-frequent shoppers. Inf. Syst. e-Bus. Manag. 2016, 15, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breugelmans, E.; Campo, K. Cross-Channel Effects of Price Promotions: An Empirical Analysis of the Multi-Channel Grocery Retail Sector. J. Retail. 2016, 92, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunten, A.; Shute, B.; Golding, S.E.; Charlton, C.; Porter, L.; Willis, Z.; Gold, N.; Saei, A.; Tempest, B.; Sritharan, N.; et al. Encouraging healthier grocery purchases online: A randomised controlled trial and lessons learned. Nutr. Bull. 2022, 47, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, K.; Breugelmans, E. Buying Groceries in Brick and Click Stores: Category Allocation Decisions and the Moderating Effect of Online Buying Experience. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 31, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, K.; Lamey, L.; Breugelmans, E.; Melis, K. Going Online for Groceries: Drivers of Category-Level Share of Wallet Expansion. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bauw, M.; De La Revilla, L.S.; Poppe, V.; Matthys, C.; Vranken, L. Digital nudges to stimulate healthy and pro-environmental food choices in E-groceries. Appetite 2022, 172, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forwood, S.E.; Ahern, A.L.; Marteau, T.M.; Jebb, S.A. Offering within-category food swaps to reduce energy density of food purchases: A study using an experimental online supermarket. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, K.L.; Lian, J.; Michels, L.; Mayer, S.; Toniato, E.; Tiefenbeck, V. Effects of Digital Food Labels on Healthy Food Choices in Online Grocery Shopping. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, L.; van Kleef, E.; Van Loo, E.J. The use of food swaps to encourage healthier online food choices: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.I.; Choi, I.Y.; Moon, H.S.; Kim, J.K. A Multi-Period Product Recommender System in Online Food Market based on Recurrent Neural Networks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marty, L.; Cook, B.; Piernas, C.; Jebb, S.A.; Robinson, E. Effects of Labelling and Increasing the Proportion of Lower-Energy Density Products on Online Food Shopping: A Randomised Control Trial in High- and Low-Socioeconomic Position Participants. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzone, L.A.; Ulph, A.; Hilton, D.; Gortemaker, I.; Tajudeen, I.A. Sustainable by Design: Choice Architecture and the Carbon Footprint of Grocery Shopping. J. Public Policy Mark. 2021, 40, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, A.O. Scarcity signaling in sales promotion: An evolutionary perspective of food choice and weight status. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, T.J.; Hamilton, S.F.; Gomez, M.; Rabinovich, E. Retail Intermediation and Local Foods. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 99, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdsson, V.; Larsen, N.M.; Alemu, M.H.; Gallogly, J.K.; Menon, R.G.V.; Fagerstrøm, A. Assisting sustainable food consumption: The effects of quality signals stemming from consumers and stores in online and physical grocery retailing. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdani, M.; Sazvar, Z. Coordinated inventory control and pricing policies for online retailers with perishable products in the presence of social learning. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 168, 108093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Liu, J. How nutrition information influences online food sales. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 1132–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Pavlidis, Y.; Jain, M.; Caster, K. Walmart Online Grocery Personalization: Behavioral Insights and Basket Recommendations; Spinger: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hercberg, S.; Touvier, M.; Salas-Salvado, J. The Nutri-Score nutrition label. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2022, 92, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.J.; Shearer, E.; Mulvaney, S.A.; Schmidt, D.; Thompson, C.; Jones, J.; Ahmad, H.; Coe, M.; Hull, P.C. Prioritization of Features for Mobile Apps for Families in a Federal Nutrition Program for Low-Income Women, Infants, and Children: User-Centered Design Approach. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e30450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, G.; Tikellis, K.; Millar, L.; Swinburn, B. Impact of ‘traffic-light’ nutrition information on online food purchases in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2011, 35, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olzenak, K.; French, S.; Sherwood, N.; Redden, J.P.; Harnack, L. How Online Grocery Stores Support Consumer Nutrition Information Needs. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomeranz, J.L.; Cash, S.B.; Springer, M.; Del Giudice, I.M.; Mozaffarian, D. Opportunities to address the failure of online food retailers to ensure access to required food labelling information in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Ahmed, M.; Zhang, T.; Weippert, M.V.; Schermel, A.; L’Abbe, M.R. The Availability and Quality of Food Labelling Components in the Canadian E-Grocery Retail Environment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslain, K.; Gustafson, C.R.; Rose, D.J. Point-of-Decision Prompts Increase Dietary Fiber Content of Consumers’ Food Choices in an Online Grocery Shopping Simulation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, P.C.; Hanson, P.; van Rens, T.; Oyebode, O. A rapid review of the evidence for children’s TV and online advertisement restrictions to fight obesity. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| General | Published in an English peer-reviewed publication or publicly available government or non-governmental report | |

| Study design | Quantitative and qualitative, could be quasi-experimental, experimental, longitudinal, cross-sectional, observational. | Conference proceedings or abstracts, dissertations or theses, news articles |

| Population | Consumers | |

| Intervention/exposure | Marketing strategies (product suggestions, promotions, price, etc.) | |

| Setting | Online grocery shopping platform | Other online settings such as social media platforms (e.g., Facebook), non-grocery e-commerce sites (e.g., clothing retailers), brand sites (e.g., Coca-Cola, Pepsi), and content streaming sites (e.g., YouTube, Hulu); physical grocery stores; television; postal mail |

| Outcomes | Food purchases as well as outcomes such as nutrient and diet quality of foods purchased. Food preferences indicated by consumers via a survey or other method of data collection. |

| References | Study Design | Setting | Population | Intervention | Outcome | Quality Assessment Tool Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arce-Urriza, M., Cebollada, J., & Tarira, M. (2017). The effect of price promotions on consumer shopping behavior across online and offline channels: Differences between frequent and non-frequent shoppers. [44] | OBS | Multi-channel (online and offline) | Shoppers that were loyalty card members at a Spanish grocery chain, who purchased orange juice at least twice during the study period, and were multi-channel shoppers | Brand-specific price promotions on orange juice | Purchase of 1-L of orange juice across online and offline channels | Quasi-experimental |

| Breugelmans, E., & Campo, K. (2016). Cross-Channel Effects of Price Promotions: An Empirical Analysis of the Multi-Channel Grocery Retail Sector. [45] | OBS | Multi-channel | Shoppers who purchase milk or cereal and shopped at Tesco in the UK | Price promotions on milk and cereal | Purchase of milk and cereal | Quasi-experimental |

| Bunten, A., Shute, B., Golding, S. E., Charlton, C., et al. (2022). Encouraging healthier grocery purchases online: A randomised controlled trial and lessons learned. [46] | EXP | Multi-channel | Shoppers with loyalty card at large chain retailer (Sainsbury’s) | Advertisement banners and ingredient lists with healthier versions of products and recipes | (1) Primary: purchases of healthier products; (2) secondary: banner clicks, purchases of standard products, overall purchases, and energy (kcal) purchased | RCT |

| Campo, K., & Breugelmans, E. (2015). Buying Groceries in Brick and Click Stores: Category Allocation Decisions and the Moderating Effect of Online Buying Experience. [47] | OBS | Multi-channel | Shoppers that were loyalty card members with at least two online and two offline purchases at a single multichannel retailer, and at least two purchases in a given category | Marketing-mix | Share of food category spending purchased online | Quasi-experimental |

| Campo, K., Lamey, L., Breugelmans, E., & Melis, K. (2021). Going Online for Groceries: Drivers of Category-Level Share of Wallet Expansion. [48] | OBS | Multi-channel | Shoppers from a household panel who started online grocery shopping during the study period at one of four major multi-channel retailers and purchased items in a food category (a) before and after they began online shopping and (b) purchased the category at more than one chain (before or after they started online shopping) of the ten chains (four multi-channel, six single-channel chains) included in the study | Marketing-mix | Share of food category spending purchased online | Quasi-experimental |

| De Bauw, M., De La Revilla, L. S., Poppe, V., Matthys, C., & Vranken, L. (2022). Digital nudges to stimulate healthy and pro-environmental food choices in E-groceries. [49] | EXP | Online (mock) | Household food decision makers (representative sample of Dutch-speaking Flemish adults) | Product recommendation agents, Nutri- and Eco- score labeling, personalized social norm messages | Nutritional quality and environmental impact of purchases | RCT |

| Forwood, S. E., Ahem, A. L., Marteau, T. M., & Jebb, S. A. (2015). Offering within-category food swaps to reduce energy density of food purchases: A study using an experimental online supermarket. [50] | EXP | Online (mock) | Nationally representative sample of adults in UK who did more than half of household’s food shopping | Food swaps with a “consented” introductory message or an “imposed” introductory message | Energy density of shopping basket and proportion of swaps accepted | RCT |

| Fuchs, K. L., Lian, J., Michels, L., Mayer, S., Toniato, E., & Tiefenbeck, V. (2022). Effects of Digital Food Labels on Healthy Food Choices in Online Grocery Shopping. [51] | EXP | Online (mock) | College students | Nutri-score labeling via a web browser extension that displayed a label next to each product | Purchases of healthier foods | RCT |

| Huyghe, E., Verstraeten, J., Geuens, M., & van Kerckhove, A. (2017). Clicks as a Healthy Alternative to Bricks: How Online Grocery Shopping Reduces Vice Purchases. * [24] | OBS/EXP | Multi-channel | College students | Traditional online mock store platform (searchable by category), uncategorized online mock store platform (click images organized like offline store), offline mock-store | Vice purchases | Quasi-experimental/RCT |

| Jansen, L., van Kleef, E., & Van Loo, E. J. (2021). The use of food swaps to encourage healthier online food choices: A randomized controlled trial. [52] | EXP | Online (mock) | Adults in the Netherlands | Swap offer, Nutri-score labeling, descriptive norm messaging | Nutrient profile score of food choices | RCT |

| Lee, H. I., Choi, I. Y., Moon, H. S., & Kim, J. K. (2020). A Multi-Period Product Recommender System in Online Food Market based on Recurrent Neural Networks. [53] | OBS | Online | Customers of online fresh food delivery service company in the United States | Product recommendation system | Accuracy of predicting shoppers’ future purchases | Quasi-experimental |

| Marty, L., Cook, B., Piernas, C., Jebb, S. A., & Robinson, E. (2020). Effects of Labelling and Increasing the Proportion of Lower-Energy Density Products on Online Food Shopping: A Randomised Control Trial in High- and Low-Socioeconomic Position Participants. [54] | EXP | Online (mock) | Adults with access to computer and internet in UK who were main shopper for their household | Labeling and assortment of lower energy density products | Energy density of items in shopping basket | RCT |

| Panzone, L. A., Ulph, A., Hilton, D., Gortemaker, I., & Tajudeen, I. A. (2021). Sustainable by Design: Choice Architecture and the Carbon Footprint of Grocery Shopping. [55] | EXP | Online (mock) | College students | Choice architecture, moral goal priming, different tax-scenarios | Carbon footprint of basket of goods chosen by the consumer | RCT |

| Peschel, A. O. (2021). Scarcity signaling in sales promotion: An evolutionary perspective of food choice and weight status. [56] | EXP | Online (mock) | Adults | Scarcity siganling and abundance signaling across type of prodcut (storable/parishable, healty/unhealthy) | Number of units chosen within the different product categories | RCT |

| Richards, T. J., Hamilton, S. F., Gomez, M., & Rabinovich, E. (2017). Retail intermediation and local foods. [57] | OBS | Online | Shoppers at Relay Foods, an online retailer in Virginia | Assortment of local products | Total sales | Quasi-experimental |

| Sigurdsson, V., Larsen, N. M., Alemu, M. H., Gallogly, J. K., Menon, R. G. V., & Fagerstrøm, A. (2020). Assisting sustainable food consumption: The effects of quality signals stemming from consumers and stores in online and physical grocery retailing. ** [58] | OBS/EXP | Multi-channel | Facebook group; adult shoppers | Quality signals (customer ratings and store recommendations) | Purchase of fresh fish | Quasi-experimental/RCT |

| Vahdani, M., & Sazvar, Z. (2022). Coordinated inventory control and pricing policies for online retailers with perishable products in the presence of social learning. [59] | EXP | Online | Shoppers at online supermarket in Iran | Expiration date based pricing and quality signals (customer ratings via online review system) | Product inventory | RCT |

| Zou, P., & Liu, J. W. (2019). How nutrition information influences online food sales. [60] | OBS | Online | Customers shopping at online retailers in China via the shopping platform Taobao | Labeling and quality signals | Food sales (six products) | Quasi-experimental |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hodges, L.; Lowery, C.M.; Patel, P.; McInnis, J.; Zhang, Q. A Systematic Review of Marketing Practices Used in Online Grocery Shopping: Implications for WIC Online Ordering. Nutrients 2023, 15, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020446

Hodges L, Lowery CM, Patel P, McInnis J, Zhang Q. A Systematic Review of Marketing Practices Used in Online Grocery Shopping: Implications for WIC Online Ordering. Nutrients. 2023; 15(2):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020446

Chicago/Turabian StyleHodges, Leslie, Caitlin M. Lowery, Priyanka Patel, Joleen McInnis, and Qi Zhang. 2023. "A Systematic Review of Marketing Practices Used in Online Grocery Shopping: Implications for WIC Online Ordering" Nutrients 15, no. 2: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020446

APA StyleHodges, L., Lowery, C. M., Patel, P., McInnis, J., & Zhang, Q. (2023). A Systematic Review of Marketing Practices Used in Online Grocery Shopping: Implications for WIC Online Ordering. Nutrients, 15(2), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020446