To Fiber or Not to Fiber: The Swinging Pendulum of Fiber Supplementation in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Key Concepts in Fiber and IBD

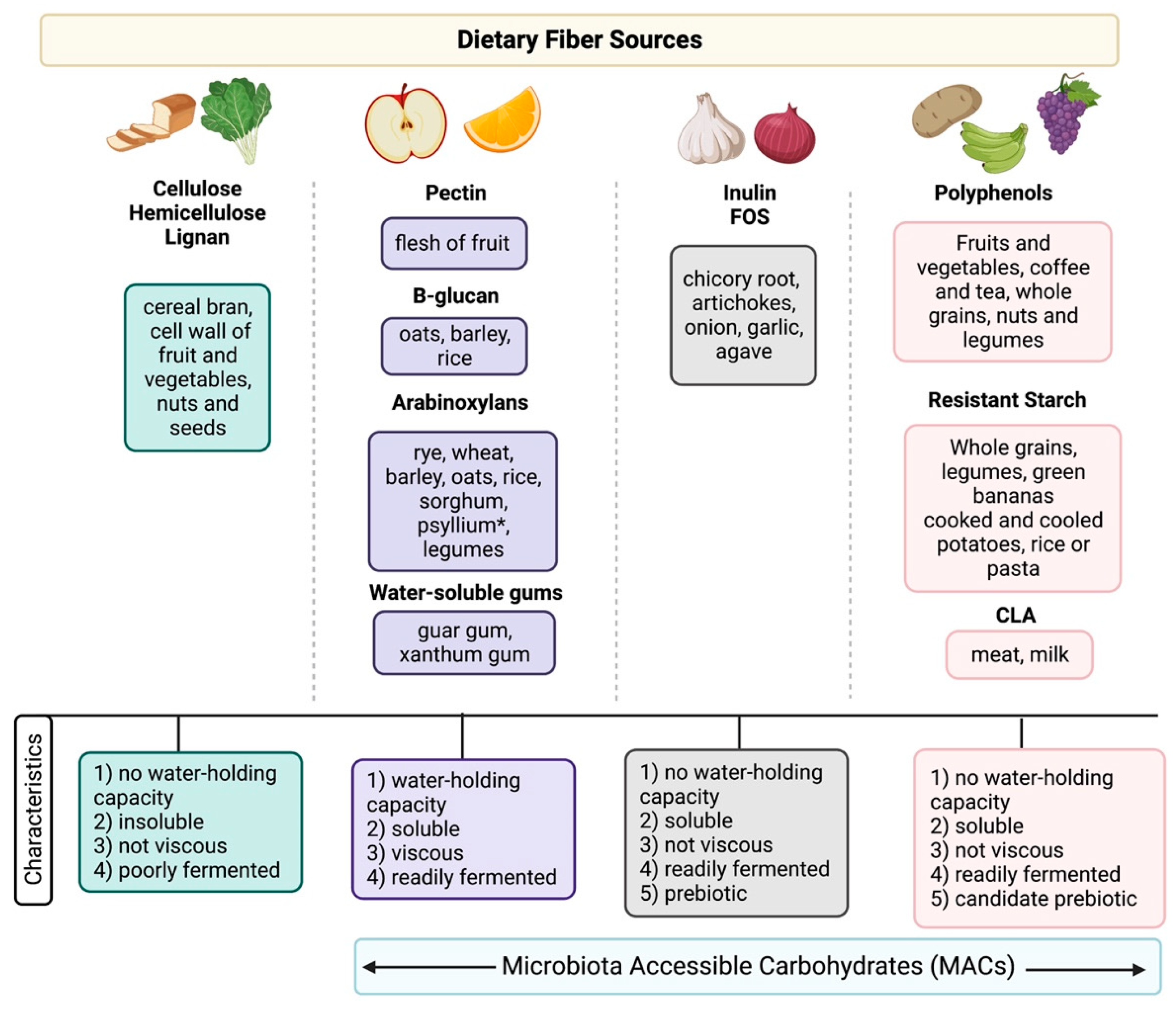

2.1. What Is Fiber?

2.2. Fiber Guidelines Are Changing

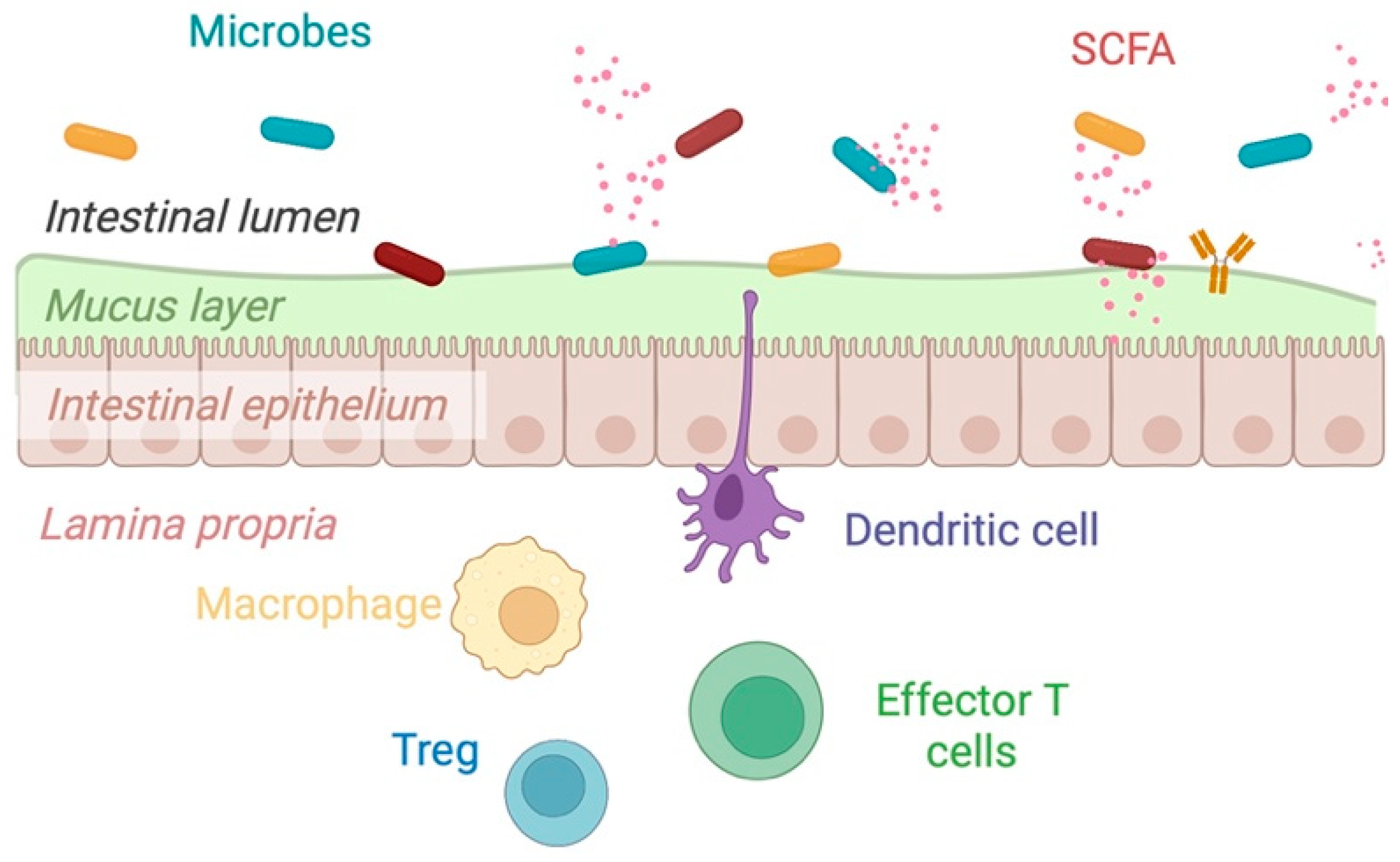

2.3. Mechanisms of Action of Dietary Fiber

2.4. Lessons from Mouse Models

3. Prebiotics

4. Novel Fiber Sources and “Candidate” Prebiotics

4.1. Resistant Starch

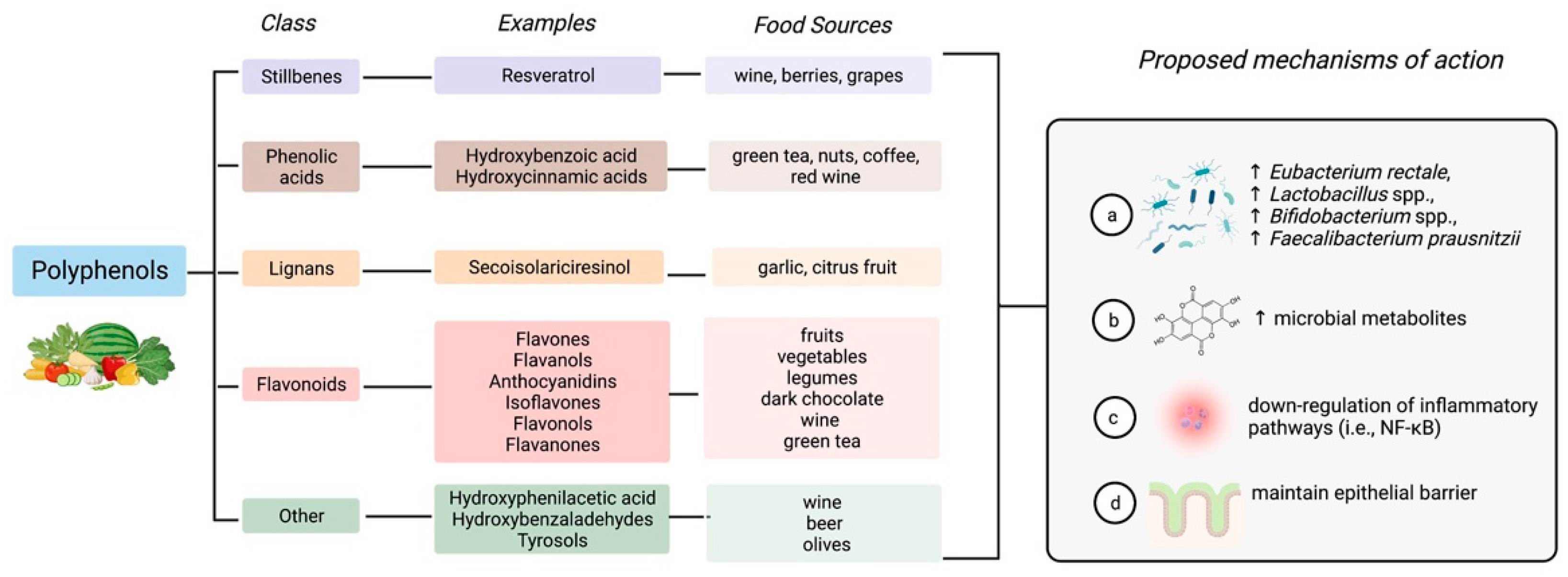

4.2. Polyphenols

4.2.1. Resveratrol

4.2.2. Curcumin

4.2.3. Quercetin

4.3. Conjugated Linoleic Acid

5. Current Limitations in Our Understanding of Fiber in IBD

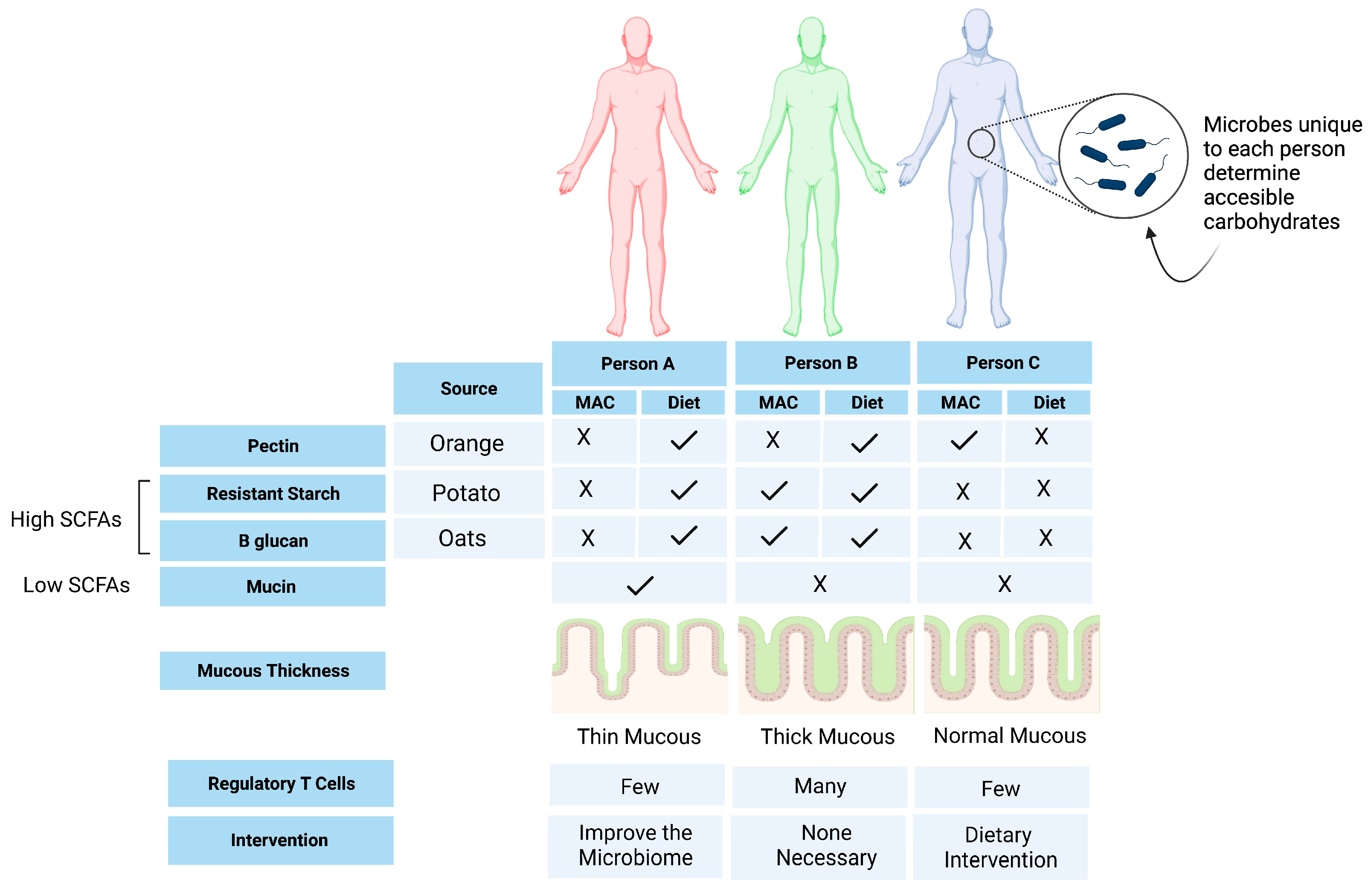

6. Opportunities for Personalized Nutrition

7. Summary and Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alatab, S.; Sepanlou, S.G.; Ikuta, K.; Vahedi, H.; Bisignano, C.; Safiri, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Nixon, M.R.; Abdoli, A.; Abolhassani, H.; et al. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Bernstein, C.N. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2022, 10, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milajerdi, A.; Ebrahimi-Daryani, N.; Dieleman, L.A.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Association of Dietary Fiber, Fruit, and Vegetable Consumption with Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Shi, L.; Wang, D.; Tang, D. Regulatory role of short-chain fatty acids in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, D.; Whelan, K.; Rossi, M.; Morrison, M.; Holtmann, G.; Kelly, J.T.; Shanahan, E.R.; Staudacher, H.M.; Campbell, K.L. Dietary fiber intervention on gut microbiota composition in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, A.; Adolphus, K. The effects of intact cereal grain fibers, including wheat bran on the gut microbiota composition of healthy adults: A systematic review. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinelli, V.; Biscotti, P.; Martini, D.; Del Bo’, C.; Marino, M.; Meroño, T.; Nikoloudaki, O.; Calabrese, F.M.; Turroni, S.; Taverniti, V.; et al. Effects of Dietary Fibers on Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Gut Microbiota Composition in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, V.; Dijkstra, G.; E Campmans-Kuijpers, M.J. Are all dietary fibers equal for patients with inflammatory bowel disease? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 80, 1179–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, H.; Mander, I.; Zhang, Z.; Armstrong, D.; Wine, E. Not All Fibers Are Born Equal; Variable Response to Dietary Fiber Subtypes in IBD. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 8, 620189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Alimentarius Commission. Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling CAC/GL 2-1985 as Last Amended 2010; Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme; Secretariat of the Codex Alimentarius Commission; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McRorie, J.W., Jr.; McKeown, N.M. Understanding the Physics of Functional Fibers in the Gastrointestinal Tract: An Evidence-Based Approach to Resolving Enduring Misconceptions about Insoluble and Soluble Fiber. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, K.; Saha, S.; Umar, S. Health Benefits of Dietary Fiber for the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRorie, J. Clinical data support that psyllium is not fermented in the gut. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Amp. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Starving our microbial self: The deleterious consequences of a diet deficient in microbiota-accessible carbohydrates. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Harris, P.J.; Ferguson, L.R. Potential benefits of dietary fibre intervention in inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Guan, X.-X.; Tang, Y.-J.; Sun, J.-F.; Wang, X.-K.; Wang, W.-D.; Fan, J.-M. Clinical effects and gut microbiota changes of using probiotics, prebiotics or synbiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2855–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, L.; Aas, A.-M.; Astrup, A.; Atkinson, F.; Baer-Sinnott, S.; Barclay, A.; Brand-Miller, J.; Brighenti, F.; Bullo, M.; Buyken, A.; et al. Dietary fibre consensus from the international carbohydrate quality consortium (Icqc). Nutrients 2020, 12, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhlmann, M.-L.; de Vos, W.M. Intrinsic dietary fibers and the gut microbiome: Rediscovering the benefits of the plant cell matrix for human health. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 954845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rosa, C.; Altomare, A.; Imperia, E.; Spiezia, C.; Khazrai, Y.M.; Guarino, M.P.L. The Role of Dietary Fibers in the Management of IBD Symptoms. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, D. Dietary fiber intake reduces risk of inflammatory bowel disease: Result from a meta-analysis. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritsch, J.; Garces, L.; Quintero, M.A.; Pignac-Kobinger, J.; Santander, A.M.; Fernández, I.; Ban, Y.J.; Kwon, D.; Phillips, M.C.; Knight, K.; et al. Low-Fat, High-Fiber Diet Reduces Markers of Inflammation and Dysbiosis and Improves Quality of Life in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 19, 1189–1199.e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotherton, C.S.; Taylor, A.G.; Bourguignon, C.; Anderson, J.G. A high-fiber diet may improve bowel function and health-related quality of life in patients with Crohn disease. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2014, 37, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhauwaert, E.; Matthys, C.; Verdonck, L.; De Preter, V. Low-Residue and Low-Fiber Diets in Gastrointestinal Disease Management. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2015, 6, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenstein, S.; Prantera, C.; Luzi, C.; D’Ubaldi, A. Low residue or normal diet in Crohn’s disease: A prospective controlled study in Italian patients. Gut 1985, 26, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomer, M.C.E.; Wilson, B.; Wall, C.L. British Dietetic Association consensus guidelines on the nutritional assessment and dietary management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 36, 336–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Bager, P.; Escher, J.; Forbes, A.; Hébuterne, X.; Hvas, C.L.; Joly, F.; Klek, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Ockenga, J.; et al. ESPEN guideline on Clinical Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 352–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Folkerts, J.; Folkerts, G.; Maurer, M.; Braber, S. Microbiota-dependent and -independent effects of dietary fibre on human health. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 177, 1363–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Sang, L.; Zhu, J.; Luo, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, K.; et al. Intermediate role of gut microbiota in vitamin B nutrition and its influences on human health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1031502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Masatoshi, H.; Ma, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, B. Role of Vitamin K in Intestinal Health. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 791565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldars-García, L.; Chaparro, M.; Gisbert, J. Systematic review: The gut microbiome and its potential clinical application in inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittayanon, R.; Lau, J.T.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Tse, F.; Yuan, Y.; Surette, M.; Moayyedi, P. Differences in Gut Microbiota in Patients With vs Without Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 930–946.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.-W.; Roh, T.-Y. Opportunistic detection of Fusobacterium nucleatum as a marker for the early gut microbial dysbiosis. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangestani, H.; Emamat, H.; Ghalandari, H.; Shab-Bidar, S. Whole Grains, Dietary Fibers and the Human Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2020, 11, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Rampelli, S.; Jeffery, I.B.; Santoro, A.; Neto, M.; Capri, M.; Giampieri, E.; Jennings, A.; Candela, M.; Turroni, S.; et al. Mediterranean diet intervention alters the gut microbiome in older people reducing frailty and improving health status: The NU-AGE 1-year dietary intervention across five European countries. Gut 2020, 69, 1218–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnava, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Severson, K.M.; Ruhn, K.A.; Yu, X.; Koren, O.; Ley, R.; Wakeland, E.K.; Hooper, L.V. The antibacterial lectin RegIIIγ promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Science 2011, 334, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, K.; Carey-Ewend, K.; Vaishnava, S. Spatial analysis of gut microbiome reveals a distinct ecological niche associated with the mucus layer. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1874815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankole, E.; Read, E.; Curtis, M.; Neves, J.; Garnett, J. The relationship between mucins and ulcerative colitis: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.S.; Seekatz, A.M.; Koropatkin, N.M.; Kamada, N.; Hickey, C.A.; Wolter, M.; Pudlo, N.A.; Kitamoto, S.; Terrapon, N.; Muller, A.; et al. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell 2016, 167, 1339–1353.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, S.; Musmeci, E.; Candeliere, F.; Amaretti, A.; Rossi, M. Identification of mucin degraders of the human gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, E.E.; Canfora, E.E.; Theis, S.; Frost, G.; Groen, A.K.; Mithieux, G.; Nauta, A.; Scott, K.; Stahl, B.; Van Harsselaar, J.; et al. Short chain fatty acids in human gut and metabolic health. Benef. Microbes 2020, 11, 411–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, C.; Meyer, R.W.; Greenhawt, M.; Pali-Schöll, I.; Nwaru, B.; Roduit, C.; Untersmayr, E.; Adel-Patient, K.; Agache, I.; Agostoni, C.; et al. Role of dietary fiber in promoting immune health—An EAACI position paper. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 77, 3185–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNulty, N.P.; Wu, M.; Erickson, A.R.; Pan, C.; Erickson, B.; Martens, E.C.; Pudlo, N.A.; Muegge, B.; Henrissat, B.; Hettich, R.; et al. Effects of Diet on Resource Utilization by a Model Human Gut Microbiota Containing Bacteroides cellulosilyticus WH2, a Symbiont with an Extensive Glycobiome. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, J.J.; McNulty, N.P.; Rey, F.E.; Gordon, J.I. Predicting a human gut microbiota’s response to diet in gnotobiotic mice. Science 2011, 333, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewellyn, S.R.; Britton, G.J.; Contijoch, E.J.; Vennaro, O.H.; Mortha, A.; Colombel, J.-F.; Grinspan, A.; Clemente, J.C.; Merad, M.; Faith, J.J. Interactions Between Diet and the Intestinal Microbiota Alter Intestinal Permeability and Colitis Severity in Mice. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1037–1046.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Koren, O.; Goodrich, J.K.; Poole, A.C.; Srinivasan, S.; Ley, R.E.; Gewirtz, A.T. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature 2015, 519, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Compher, C.; Bonhomme, B.; Liu, Q.; Tian, Y.; Walters, W.; Nessel, L.; Delaroque, C.; Hao, F.; Gershuni, V.; et al. Randomized Controlled-Feeding Study of Dietary Emulsifier Carboxymethylcellulose Reveals Detrimental Impacts on the Gut Microbiota and Metabolome. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Ince, J.; Duncan, S.H.; Webster, L.M.; Holtrop, G.; Ze, X.; Brown, D.; Stares, M.D.; Scott, P.; Bergerat, A.; et al. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J. 2010, 5, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanauchi, O.; Suga, T.; Tochihara, M.; Hibi, T.; Naganuma, M.; Homma, T.; Asakura, H.; Nakano, H.; Takahama, K.; Fujiyama, Y.; et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis by feeding with germinated barley foodstuff: First report of a multicenter open control trial. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 37 (Suppl. 1), 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghfoori, Z.; Navai, L.; Shakerhosseini, R.; Somi, M.H.; Nikniaz, Z.; Norouzi, M.F. Effects of an oral supplementation of germinated barley foodstuff on serum tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6 and -8 in patients with ulcerative colitis. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2011, 48, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bañares, F.; Hinojosa, J.; Sánchez-Lombraña, J.L.; Navarro, E.; Martínez-Salmerón, J.F.; García-Pugés, A.; González-Huix, F.; Riera, J.; González-Lara, V.; Domínguez-Abascal, F.; et al. Randomized clinical trial of Plantago ovata seeds (dietary fiber) as compared with mesalamine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis. Spanish Group for the Study of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU). Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 94, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallert, C.; Kaldma, M.; Petersson, B.G. Ispaghula husk may relieve gastrointestinal symptoms in ulcerative colitis in remission. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1991, 26, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellas, F.; Borruel, N.; Torrejon, A.; Varela, E.; Antolin, M.; Guarner, F.; Malagelada, J.-R. Oral oligofructose-enriched inulin supplementation in acute ulcerative colitis is well tolerated and associated with lowered faecal calprotectin. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 25, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, J.O.; Whelan, K.; Stagg, A.J.; Gobin, P.; Al-Hassi, H.O.; Rayment, N.; Kamm, M.A.; Knight, S.C.; Forbes, A. Clinical, microbiological, and immunological effects of fructo-oligosaccharide in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut 2006, 55, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhong, Y.; Dong, D.; Zheng, Z.; Hu, J. Gut microbial utilization of xylan and its implication in gut homeostasis and metabolic response. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 286, 119271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, U.K.; Kango, N.; Pletschke, B. Hemicellulose-Derived Oligosaccharides: Emerging Prebiotics in Disease Alleviation. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 670817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater, C.; Calvete-Torre, I.; Ruiz, L.; Margolles, A. Arabinoxylan and Pectin Metabolism in Crohn’s Disease Microbiota: An In Silico Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.; Eyice, Ö.; Koumoutsos, I.; Lomer, M.C.; Irving, P.M.; Lindsay, J.O.; Whelan, K. Prebiotic galactooligosaccharide supplementation in adults with ulcerative colitis: Exploring the impact on peripheral blood gene expression, gut microbiota, and clinical symptoms. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.L.; Hedin, C.; Koutsoumpas, A.; Ng, S.C.; McCarthy, N.; Hart, A.L.; Kamm, M.A.; Sanderson, J.D.; Knight, S.C.; Forbes, A.; et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fructo- oligosaccharides in active Crohn’s disease. Gut 2011, 60, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedin, C.R.; McCarthy, N.E.; Louis, P.; Farquharson, F.M.; McCartney, S.; Stagg, A.J.; Lindsay, J.O.; Whelan, K. Prebiotic fructans have greater impact on luminal microbiology and CD3+ T cells in healthy siblings than patients with Crohn’s disease: A pilot study investigating the potential for primary prevention of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5009–5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joossens, M.; De Preter, V.; Ballet, V.; Verbeke, K.; Rutgeerts, P.; Vermeire, S. Effect of oligofructose-enriched inulin (OF-IN) on bacterial composition and disease activity of patients with Crohn’s disease: Results from a double-blinded randomised controlled trial. Gut 2011, 61, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Zaragoza, E.; Sánchez-Zapata, E.; Sendra, E.; Sayas, E.; Navarro, C.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A. Resistant starch as prebiotic: A review. Starch-Stärke 2011, 63, 406–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, T.; Dincer, E. Effect of resistant starch types as a prebiotic. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, Y. Align resistant starch structures from plant-based foods with human gut microbiome for personalized health promotion. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topping, D.L.; Fukushima, M.; Bird, A.R. Resistant starch as a prebiotic and synbiotic: State of the art. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasjim, J.; Ai, Y.; Jane, J.-L. Novel Applications of Amylose-Lipid Complex as Resistant Starch Type 5. In Resistant Starch: Sources Applications and Health Benefits; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Chapter 4; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montroy, J.; Berjawi, R.; Lalu, M.M.; Podolsky, E.; Peixoto, C.; Sahin, L.; Stintzi, A.; Mack, D.; Fergusson, D.A. The effects of resistant starches on inflammatory bowel disease in preclinical and clinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ze, X.; Duncan, S.H.; Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Ruminococcus bromii is a keystone species for the degradation of resistant starch in the human colon. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenguer, A.; Duncan, S.H.; Calder, A.G.; Holtrop, G.; Louis, P.; Lobley, G.E.; Flint, H.J. Two routes of metabolic cross-feeding between Bifidobacterium adolescentis and butyrate-producing anaerobes from the human gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 3593–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Day, A.; Barrett, J.; Vanlint, A.; Andrews, J.M.; Costello, S.P.; Bryant, R.V. Habitual dietary fibre and prebiotic intake is inadequate in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Findings from a multicentre cross-sectional study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 34, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghurst, P.A.; Baghurst, K.I.; Record, S.J. Dietary fibre, non-starch polysaccharides and resistant starch—A review. Food Aust. 1996, 48, S1–S36. [Google Scholar]

- Sobh, M.; Montroy, J.; Daham, Z.; Sibbald, S.; Lalu, M.; Stintzi, A.; Mack, D.; Fergusson, D.A. Tolerability and SCFA production after resistant starch supplementation in humans: A systematic review of randomized controlled studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swallah, M.S.; Sun, H.; Affoh, R.; Fu, H.; Yu, H. Antioxidant Potential Overviews of Secondary Metabolites (Polyphenols) in Fruits. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 9081686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DArchivio, M.; Filesi, C.; Di Benedetto, R.; Gargiulo, R.; Giovannini, C.; Masella, R. Polyphenols, dietary sources and bioavailability. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2007, 43, 348. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, S.; Del Bo’, C.; Marino, M.; Gargari, G.; Cherubini, A.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; Hidalgo-Liberona, N.; Peron, G.; González-Dominguez, R.; Kroon, P.A.; et al. Polyphenols and Intestinal Permeability: Rationale and Future Perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 68, 1816–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Saeed, F.; Anjum, F.M.; Afzaal, M.; Tufail, T.; Bashir, M.S.; Ishtiaq, A.; Hussain, S.; Suleria, H.A.R. Natural polyphenols: An overview. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortt, C.; Hasselwander, O.; Meynier, A.; Nauta, A.; Fernández, E.N.; Putz, P.; Rowland, I.; Swann, J.; Türk, J.; Vermeiren, J.; et al. Systematic review of the effects of the intestinal microbiota on selected nutrients and non-nutrients. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Nigam, M.; Sener, B.; Kilic, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Resveratrol: A double-edged sword in health benefits. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsami-Kor, M.; Daryani, N.E.; Asl, P.R.; Hekmatdoost, A. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Resveratrol in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled Pilot Study. Arch. Med. Res. 2015, 46, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsamikor, M.; Daryani, N.E.; Asl, P.R.; Hekmatdoost, A. Resveratrol Supplementation and Oxidative/Anti-Oxidative Status in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled Pilot Study. Arch. Med. Res. 2016, 47, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S.; Danesi, F.; Del Rio, D.; Silva, P. Resveratrol and inflammatory bowel disease: The evidence so far. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2018, 31, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowd, V.; Kanika; Jori, C.; Chaudhary, A.A.; Rudayni, H.A.; Rashid, S.; Khan, R. Resveratrol and resveratrol nano-delivery systems in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 109, 109101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.R.; Romi, M.D.; Ferreira, D.M.T.P.; Zaltman, C.; Soares-Mota, M. The use of curcumin as a complementary therapy in ulcerative colitis: A systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulart, R.D.A.; Barbalho, S.M.; Lima, V.M.; de Souza, G.A.; Matias, J.N.; Araújo, A.C.; Rubira, C.J.; Buchaim, R.L.; Buchaim, D.V.; de Carvalho, A.C.A.; et al. Effects of the Use of Curcumin on Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Food 2021, 24, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassaninasab, A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Tomita-Yokotani, K.; Kobayashi, M. Discovery of the curcumin metabolic pathway involving a unique enzyme in an intestinal microorganism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-B.; Bae, D.-W.; Clavio, N.A.B.; Zhao, L.; Jeong, C.-S.; Choi, B.M.; Macalino, S.J.Y.; Cha, H.-J.; Park, J.-B.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Structural and Biochemical Characterization of the Curcumin-Reducing Activity of CurA from Vibrio vulnificus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 10608–10616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinfar, H.; Payandeh, N.; ElhamKia, M.; Abbasi, F.; Alaghi, A.; Djafari, F.; Eslahi, M.; Gohari, N.S.F.; Ghorbaninejad, P.; Hasanzadeh, M.; et al. Administration of dietary antioxidants for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 63, 102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, X. Polyphenols intervention is an effective strategy to ameliorate inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 72, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommelaer, G.; Laharie, D.; Nancey, S.; Hebuterne, X.; Roblin, X.; Nachury, M.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Fumery, M.; Richard, D.; Pereira, B.; et al. Oral Curcumin No More Effective Than Placebo in Preventing Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease After Surgery in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 18, 1553–1560.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, K.; Ikeya, K.; Bamba, S.; Andoh, A.; Yamasaki, H.; Mitsuyama, K.; Nasuno, M.; Tanaka, H.; Matsuura, A.; Kato, M.; et al. Tu1716–Highly Bioavailable Curcumin (Theracurmin®) for Crohn’s Disease: Randomized, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, S-1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Ikram, M.; Mulla, Z.S.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Taha, A.E.; Algammal, A.M.; Elewa, Y.H.A. The pharmacological activity, biochemical properties, and pharmacokinetics of the major natural polyphenolic flavonoid: Quercetin. Foods 2020, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waslyk, A.; Bakovic, M. Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2021, 4, 94–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Wei, P.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Zeng, J.; Ma, X.; Tang, J. Preclinical evidence for quercetin against inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 2035–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, G.; Ghiasvand, R.; Feizi, A.; Ghanadian, S.M.; Karimian, J. The effect of quercetin supplementation on selected markers of inflammation and oxidative stress. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2012, 17, 637–641. [Google Scholar]

- Viladomiu, M.; Hontecillas, R.; Bassaganya-Riera, J. Modulation of inflammation and immunity by dietary conjugated linoleic acid. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 785, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzenthaler, K.L.; McGuire, M.K.; Shultz, T.D.; Falen, R.; Dasgupta, N.; McGuire, M.A. Estimation of conjugated linoleic acid intake by written dietary assessment methodologies underestimates actual intake evaluated by food duplicate methodology. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1548–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorissen, L.; Raes, K.; Weckx, S.; Dannenberger, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L.; De Smet, S. Production of conjugated linoleic acid and conjugated linolenic acid isomers by Bifidobacterium species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 2257–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Han, L.; Wang, D.; Li, P.; Shahidi, F. Conjugated Fatty Acids in Muscle Food Products and Their Potential Health Benefits: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13530–13540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassaganya-Riera, J.; Hontecillas, R.; Horne, W.T.; Sandridge, M.; Herfarth, H.H.; Bloomfeld, R.; Isaacs, K.L. Conjugated linoleic acid modulates immune responses in patients with mild to moderately active Crohn’s disease. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivers, S.; Lagos, L.; Garbers, P.; La Rosa, S.L.; Westereng, B. Technical pipeline for screening microbial communities as a function of substrate specificity through fluorescent labelling. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Van Treuren, W.; Fischer, C.R.; Merrill, B.D.; DeFelice, B.C.; Sanchez, J.M.; Higginbottom, S.K.; Guthrie, L.; Fall, L.A.; Dodd, D.; et al. A metabolomics pipeline for the mechanistic interrogation of the gut microbiome. Nature 2021, 595, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, A.; Sieber, J.R.; Schmidt, A.W.; Waldron, C.; Theis, K.R.; Schmidt, T.M. Variable responses of human microbiomes to dietary supplementation with resistant starch. Microbiome 2016, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Christophersen, C.T.; Bird, A.R.; Conlon, M.A.; Rosella, O.; Gibson, P.R.; Muir, J.G. Abnormal fibre usage in UC in remission. Gut 2014, 64, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, H.K.; Bording-Jorgensen, M.; Santer, D.M.; Zhang, Z.; Valcheva, R.; Rieger, A.M.; Kim, J.S.-H.; Dijk, S.I.; Mahmood, R.; Ogungbola, O.; et al. Unfermented β-fructan Fibers Fuel Inflammation in Select Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Gastroenterology 2022, 164, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.; Lane, J.A.; Smith, G.J.; Grimaldi, K.A.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Precision nutrition and the microbiome part ii: Potential opportunities and pathways to commercialization. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeevi, D.; Korem, T.; Zmora, N.; Israeli, D.; Rothschild, D.; Weinberger, A.; Ben-Yacov, O.; Lador, D.; Avnit-Sagi, T.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; et al. Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses. Cell 2015, 163, 1079–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, C.; Lam, Y.Y.; Zhao, L. Guild-based analysis for understanding gut microbiome in human health and diseases. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudlo, N.A.; Urs, K.; Crawford, R.; Pirani, A.; Atherly, T.; Jimenez, R.; Terrapon, N.; Henrissat, B.; Peterson, D.; Ziemer, C.; et al. Phenotypic and Genomic Diversification in Complex Carbohydrate-Degrading Human Gut Bacteria. mSystems 2022, 7, e00947-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolonen, A.C.; Beauchemin, N.; Bayne, C.; Li, L.; Tan, J.; Lee, J.; Meehan, B.M.; Meisner, J.; Millet, Y.; LeBlanc, G.; et al. Synthetic glycans control gut microbiome structure and mitigate colitis in mice. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Study Design (n = 10) | Disease Type and Status | Intervention | Primary Endpoint | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanauchi et al. (2002) [49] | Open-label trial (n = 18) | Active UC (mild-moderate) | Standard medical therapy (control) or Standard medical therapy + GBF (20–30 g/day) for 4 weeks | Response to treatment measured by clinical disease score (Lichtiger method) | After 4 weeks of GBF administration, the clinical disease score in the GBF group was significantly lower than in the control group (p < 0.05). |

| Faghfoori et al. (2011) [50] | Randomized control trial (n = 41) | UC in remission | GBF (30 g/day) + standard medical therapy or standard medical therapy (control) | Changes to pre-treatment and post-treatment values of serum TNF-a, IL-6 and IL-8 | Serum IL-6 and IL-8 decreased significantly in the GBF-treated group (p = 0.034 and p = 0.013). A trend towards increased TNF-α was seen in the non-GBF treated group (p = 0.08) |

| Casellas et al. (2007) [53] | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial (n = 15) | Active UC (mild-moderate) | Oligofructose-enriched inulin (12 g/day) + mesalazine (3 g/day) or placebo + mesalazine (3 g/day) for 2 weeks (control) | Reduction in inflammation as measured by fecal calprotectin and human DNA in feces | Oligofructose-enriched inulin plus mesalazine was associated with reduced fecal calprotectin (day 0: 4377 ± 659 ug/g; day 14: 1211 ± 449 ug/g, p < 0.05) but not in the placebo group. No changes were observed to DNA in feces in either group |

| Wilson et al. (2021) [58] | Open-label trial (n = 17) | Active UC (mild) | GOS (2.8 g/day) for 6 weeks | Changes in expression of any immune-related gene using a microarray of all genes expressed in the peripheral blood | No significant differences In immune gene expression were detected No change in disease activity, however a significant reduction in loose stools (p = 0.048) and urgency (p = 0.011) was observed No change in Bifidobacterium |

| Benjamin et al. (2011) [59] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 103) | Active CD | Oligofructose/inulin (15 g/day) or placebo for 4 weeks | Clinical response at week 4 (decrease in CDAI of ≥ 70 points) | No significant difference in the number of patients achieving a clinical response between the oligofructose/inulin and placebo groups (12 (22%) vs. 19 (39%), p = 0.067) Oligofructose/inulin had reduced proportions of interleukin (IL)-6-positive lamina propria DC and increased DC staining of IL-10 (p < 0.05) No change in fecal concentration of Bifidobacterium and F. prausnitzii |

| Hedin et al. (2021) [60] | Open-label trial (n = 19) | CD in remission | Oligofructose/inulin (15 g/day) for 3 weeks | Reduction in fecal calprotectin | Fecal calprotectin did not significantly change (p = 0.08) Fecal concentrations of Bifidobacteria and Bifidobacterium longum increased There was a significant reduction in intestinal permeability between baseline and following oligofructose/inulin supplementation in patients (urinary lactulose-rhamnose ratio from median 0.066, IQR 0.092 to median 0.041, IQR 0.038, p = 0.049) |

| Joossens et al. (2011) [61] | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial (n = 67) | Inactive to mild to moderately active CD | 10 g/day oligofructose/inulin twice daily for one month | Reduction in disease activity measured by Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) and changes to the microbiota | A significant increase in B. longum was seen in the treatment (ITT p = 0.03) Sub-group analyses revealed a significant decrease in HBI from 7 to 5 following treatment (p = 0.03) |

| Lindsay et al. (2006) [54] | Open-label trial (n = 10) | Active ileocolonic CD | 15 g/day oligofructose/inulin for 3 weeks | Reduction in disease activity measured by Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) | There was a significant reduction in HBI from baseline 9.8 (SD 3.1) to 6.9 (3.4) at week 3 (p = 0.01) FOS induced a marked increase in fecal Bifidobacteria concentrations (baseline 8.8 (0.9) to FOS 9.4 (0.9) log cell/g dry feces; p = 0.005) |

| Fernández-Bañares et al. (1999) [51] | Open-label, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial (n = 94) | UC in remission | Plantago ovata seeds (20 g/day), mesalamine (1500 mg/day), or Plantago ovata seeds (20 g/day) + mesalamine (1500 mg/day) for 12 months | Maintenance of remission at 12 months | The treatment failure rate was 40% (14/35 patients) in the Plantago ovata seed group, 35% (13/37) in the mesalamine group, and 30% (9/30) in the Plantago ovata seed plus mesalamine group. The probability of remission was similar between groups (p = 0.67) |

| Hallert et al. (1991) [52] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial (n = 29) | UC in remission | Ispaghula husk (4 g twice daily) or placebo for 2 months each | Reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms: abdominal pain, diarrhea, loose stools, urgency, bloating, mucus, incomplete evacuation, constipation | Ispaghula husk was consistently superior and associated with a significantly higher rate of improvement (69%) in gastrointestinal symptoms than placebo (24%) (p < 0.001) |

| RS Types | Definition | Food Sources | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RS 1 | Physically inaccessible starch found entrapped within the protein matrix or non-starch components of the plant cell wall | Unprocessed whole grains, legumes such as soybean seeds, beans, lentils, and dried peas | Li et al., 2021 [64] |

| RS 2 | Resistant starch granules | Raw potato, green banana, high amylose cornstarch | Li et al., 2021 [64] |

| RS 3 | Obtained by retrogradation process upon cooking and cooling of starch-containing foods | Cooked or cooled rice, pasta or potatoes, cornflakes | Topping et al., 2003 [65] |

| RS 4 | Starch-modified through chemical processes | Food additives derived from corn, potatoes, or rice are used for formulations that require smoothness, pulpy texture, flowability, low-pH storage, and high-temperature storage | Fuentes-Zaragoza et al., 2011 [62] |

| RS 5 | Starch obtained by complex formation between high amylose starch with the lipids | Resistant maltodextrin, high-amylose starch | Hasjim et al., 2013 [66] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haskey, N.; Gold, S.L.; Faith, J.J.; Raman, M. To Fiber or Not to Fiber: The Swinging Pendulum of Fiber Supplementation in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051080

Haskey N, Gold SL, Faith JJ, Raman M. To Fiber or Not to Fiber: The Swinging Pendulum of Fiber Supplementation in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2023; 15(5):1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051080

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaskey, Natasha, Stephanie L. Gold, Jeremiah J. Faith, and Maitreyi Raman. 2023. "To Fiber or Not to Fiber: The Swinging Pendulum of Fiber Supplementation in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Nutrients 15, no. 5: 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051080

APA StyleHaskey, N., Gold, S. L., Faith, J. J., & Raman, M. (2023). To Fiber or Not to Fiber: The Swinging Pendulum of Fiber Supplementation in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients, 15(5), 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051080