A Systems Approach to Identify Factors Influencing Participation in Two Tribally-Administered WIC Programs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.1.1. WIC Program in the Midwest U.S.

2.1.2. WIC Program in the Southwest U.S.

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

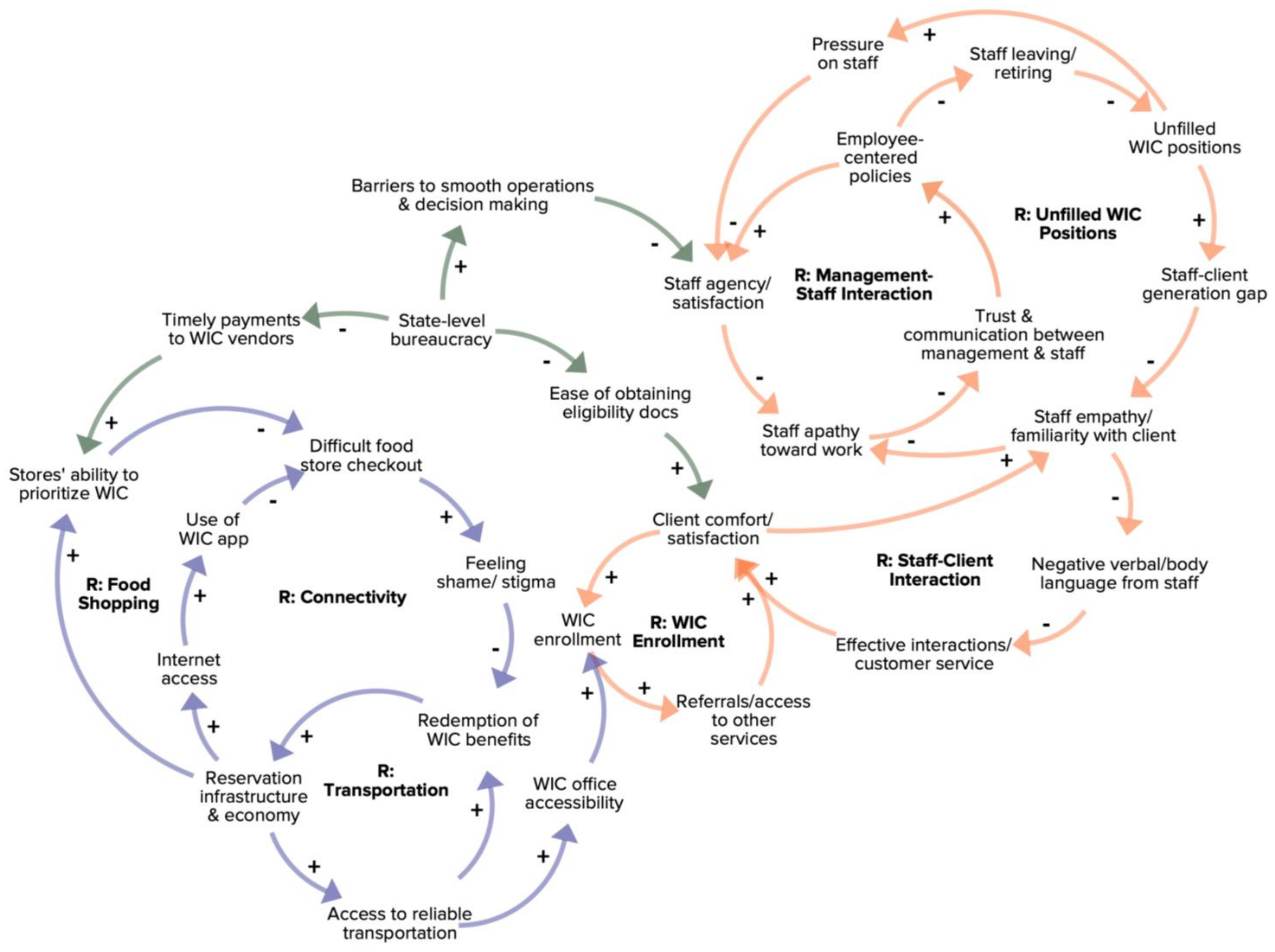

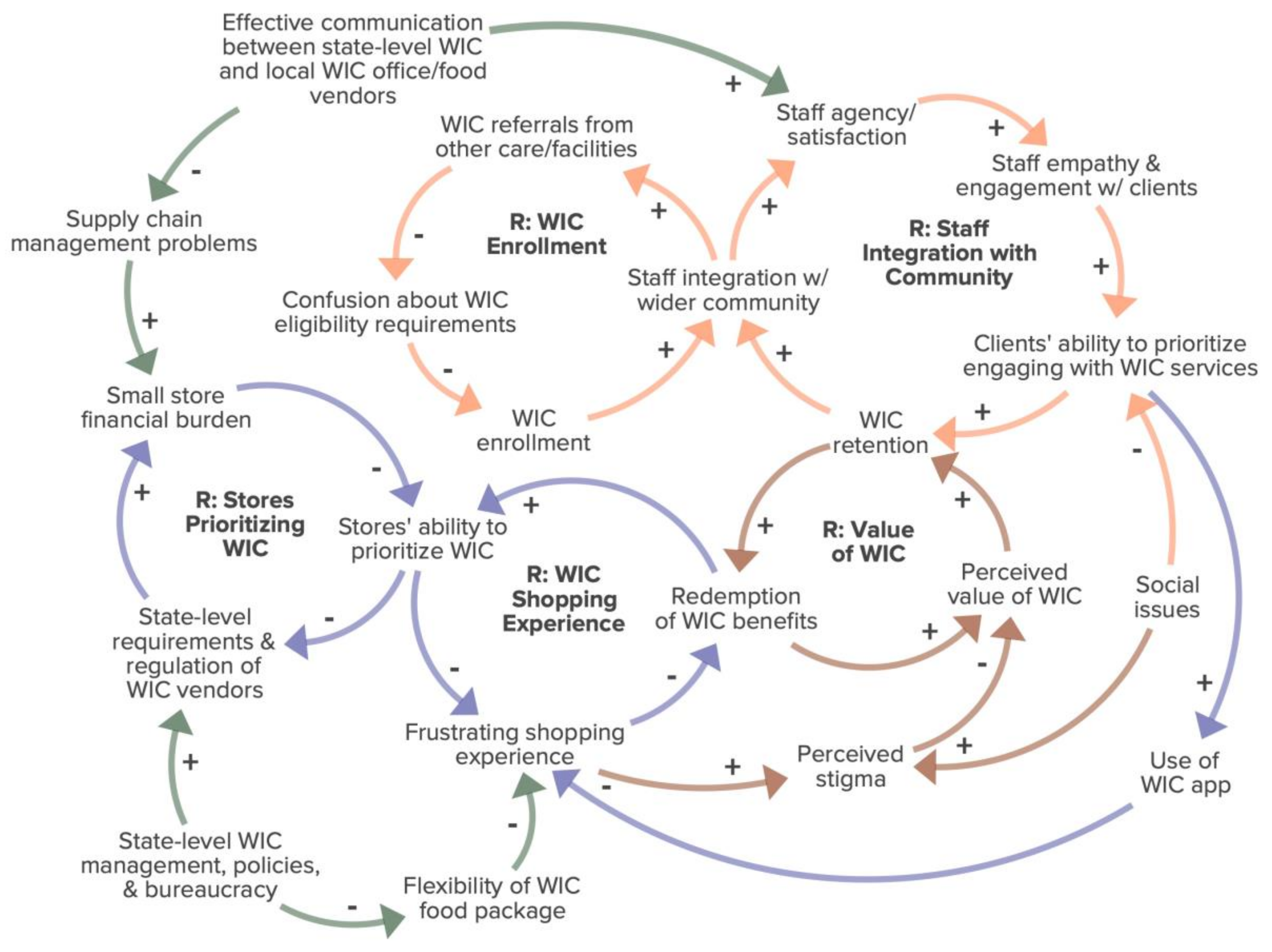

3.1. Theme 1: Reservation and Food Store Infrastructure

“[The free phone from Cellular One] is pretty good. I didn’t have any trouble because I go here and there with my children for our appointments, and even in border towns I was able to still get phone calls and messages. But not sure how the internet would work [in rural areas]. I have to connect to WiFi to get internet. I don’t have it on the phone.”

“The WIC items have to [be scanned] on the little WIC EBT machine, and the other items are going to come through the register. I wish we could update our register system and do everything on the register, but money doesn’t allow that right now.”

“A little local store here, they have a WIC shelf. Everything on that shelf is for WIC—it’s perfect. That works, and I praise them for that.”

3.2. Theme 2: WIC Staff Interactions and Integration with the Community

“…we have a really good staff and I know that our tribe in particular, in our health center, you know we’re very resilient no matter what happens… I’m not doing it by myself; I have this great group of people to work with.”

“…their customer service, I’m not a big fan of it. I would be nice and cooperative and listen to just hurry up and get out of there.”

3.3. Theme 3: State-level Administration and Bureaucracy

“…even just like getting an ID, getting a driver’s license, all of those things are so much more difficult because I live on the Navajo Nation. I mean, I’m 27 now and I still don’t have my driver’s license because it’s so difficult to go through the bureaucratic process.”

“Our [WIC EBT reader] machine went down when they did an update, and when we called the state to find out about it, they said ‘well you know you’re not set up with the new machines’…and it’s like, really? Why didn’t you give us a heads up and get these new WIC machines in here? So we ended up going, it was a good two weeks, without WIC…”

“With WIC I have to stay within their guidelines, you know, and culturally… I can’t give [participants] that culture. Because technically I gotta stay within my scope. So that’s where I have a hard time with WIC.”

3.4. Theme 4: Value of WIC

“It’s really hard to budget. Because I get paid every two weeks, um, when it gets close to my next paycheck I look at my account and I have maybe $20 left. If I had to buy the formula, straight up, I don’t know what I’d do [without WIC].”

“The local gas station used to accept [WIC], except if there was a line, you’d be put in the back of the line to just let people who were getting gas or getting this or that go in front, and then they would process you last. So that really sucked, and people complained, and now they don’t accept WIC, which also sucks because it was the closest store to me.”

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, S.; Hongu, N.; Daily, J.W. Native American Foods: History, Culture, and Influence on Modern Diets. J. Ethn. Foods 2016, 3, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurney, R.M.; Caniglia, B.S.; Mix, T.L.; Baum, K.A. Native American Food Security and Traditional Foods: A Review of the Literature. Sociol. Compass 2015, 9, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leason, J.L. Exploring the Complex Context of Canadian Indigenous Maternal Child-Health through Maternity Experiences: The Role of Social Determinants of Health. Soc. Determ. Health 2018, 4, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, J.L.; Jones, E.J.; Bohn, D.; McCage, S.; Goforth Parker, J.; Parker, M.; Pierce, S.L.; Campbell, J. Maternal Mortality Among American Indian/Alaska Native Women: A Scoping Review. J. Womens Health 2021, 30, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.K.; Yu, S.M. Infant Mortality in the United States, 1915–2017: Large Social Inequalities Have Persisted for Over a Century. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS 2019, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiotis, P.P.; Kramer-LeBlanc, C.S.; Kennedy, E.T. Maintaining Nutrition Security and Diet Quality: The Role of the Food Stamp Program and WIC. Fam. Econ. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 11, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Colman, S.; Nichols-Barrer, I.P.; Redline, J.E.; Devaney, B.L.; Ansell, S.V.; Joyce, T. Effects of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): A Review of Recent Research; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Guan, A.; Hamad, R.; Batra, A.; Bush, N.R.; Tylavsky, F.A.; LeWinn, K.Z. The Revised Wic Food Package and Child Development: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e20201853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V. The Food Assistance Landscape: FY 2016 Annual Report; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Caulfield, L.E.; Bennett, W.L.; Gross, S.M.; Hurley, K.M.; Ogunwole, S.M.; Venkataramani, M.; Lerman, J.L.; Zhang, A.; Sharma, R.; Bass, E.B. Maternal and Child Outcomes Associated With the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Food and Nutrition Service. WIC Data Tables. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Isaacs, S.E.; Shriver, L.; Haldeman, L. Qualitative Analysis of Maternal Barriers and Perceptions to Participation in a Federal Supplemental Nutrition Program in Rural Appalachian North Carolina. J. Appalach Health 2020, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Liu, H. Concerns and Structural Barriers Associated with WIC Participation among WIC-Eligible Women. Public Health Nurs. 2016, 33, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luke, D.A.; Stamatakis, K.A. Systems Science Methods in Public Health: Dynamics, Networks, and Agents. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2012, 33, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vennix, J.A.M. Group Model Building: Facilitating Team Learning Using System Dynamics, 1st ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 9780471953555. [Google Scholar]

- Mui, Y.; Ballard, E.; Lopatin, E.; Thornton, R.L.J.; Pollack Porter, K.M.; Gittelsohn, J. A Community-Based System Dynamics Approach Suggests Solutions for Improving Healthy Food Access in a Low-Income Urban Environment. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Nembhard, H.B.; Curry, W.; Ghahramani, N.; Hwang, W. A Systems Thinking Approach to Prospective Planning of Interventions for Chronic Kidney Disease Care. Health Syst. 2017, 6, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.; Andersen, D.F. Building Confidence in Causal Maps Generated from Purposive Text Data: Mapping Transcripts of the Federal Reserve. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2012, 28, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michigan WIC Deduplicated Enrollment Count by Local Agency of Service FY2021. 2022. Available online: https://Www.Michigan.Gov/-/Media/Project/Websites/Mdhhs/Folder50/Folder9/FY_2021_Dedup_enrlmnt_by_svc.Pdf?Rev=d9db054a42c04d0d9b3f642ee336c7a7 (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Food and Nutrition Service. Monthly Data—Level Participation by Category and Program Costs FY2021. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Kumu. Available online: https://kumu.io/ (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Gago, C.M.; Wynne, J.O.; Moore, M.J.; Cantu-Aldana, A.; Vercammen, K.; Zatz, L.Y.; May, K.; Andrade, T.; Mendoz, T.; Stone, S.L.; et al. Caregiver Perspectives on Underutilization of WIC: A Qualitative Study. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021053889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvenet, C.; de Marco, M.; Barnes, C.; Ammerman, A.S. WIC Recipients in the Retail Environment: A Qualitative Study Assessing Customer Experience and Satisfaction. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 416–424.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, S.E.; Martinez, C.E.; Paolicelli, C.; Ritchie, L.D.; Weinfield, N.S. Predictors of WIC Participation Through 2 Years of Age. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henchy, G.; Cheung, M.; Weill, J. WIC in Native American Communities: Building a Healthier America; National WIC Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- USDA, the Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation Special Nutrition Programs. The Characteristics of Native American WIC Participants, On and Off Reservations; USDA Nutrition Assistance Program Report Series; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- Henchy, G. Making WIC Work Better: Making WIC Work Better: Strategies to Reach More Women and Children and Strengthen Benefits Use Acknowledgments; National WIC Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, M.C.; Beaird, J.; Steeves, E.T.A. WIC Participants’ Perspectives About Online Ordering and Technology in the WIC Program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, H.J.; Palar, K.; Ranadive, N.A.; Turan, J.M.; Kushel, M.; Weiser, S.D. “The Land of the Sick and the Land of the Healthy”: Disability, Bureaucracy, and Stigma among People Living with Poverty and Chronic Illness in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 190, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herd, P.; Moynihan, D. How Administrative Burdens Can Harm Health. Health Aff. 2020, 43, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, M.J.; Phan, K.; McGuirt, J.T.; Ostrander, A.; Ademu, L.; Seibold, M.; McCallops, K.; Tracy, T.; Fleischhacker, S.E.; Karpyn, A. Usda Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (Wic) Vendor Criteria: An Examination of Us Administrative Agency Variations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newes-Adeyi, G.; Helitzer, D.L.; Roter, D.; Caulfield, L.E. Improving Client–Provider Communication: Evaluation of a Training Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Professionals in New York State. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 55, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbell, M.G.; Seth, J.G.; Atwood, R.D.; Ray, T.C. A Client-Centered Nutrition Education Model: Lessons Learned from Texas WIC. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogu, L.C.; Janakiram, J.; Hoffman, H.J.; McDonough, L.; Valencia, A.P.; Mackey, E.R.; Klein, C.J. Hispanic Overweight and Obese Children: Thirty Cases Managed With Standard WIC Counseling or Motivational Interviewing. Infant Child Adolesc. Nutr. 2014, 6, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodur, G.M.; Shen, Y.; Kodish, S.; Oddo, V.M.; Antiporta, D.A.; Jock, B.; Jones-Smith, J.C. Food Environments around American Indian Reservations: A Mixed Methods Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jernigan, V.B.B.; Salvatore, A.L.; Styne, D.M.; Winkleby, M. Addressing Food Insecurity in a Native American Reservation Using Community-Based Participatory Research. Health Educ. Res. 2012, 27, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pindus, N.; Hafford, C. Food Security and Access to Healthy Foods in Indian Country: Learning from the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiler, A.M.; Hergesheimer, C.; Brisbois, B.; Wittman, H.; Yassi, A.; Spiegel, J.M. Food Sovereignty, Food Security and Health Equity: A Meta-Narrative Mapping Exercise. Health Policy Plan 2015, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finegold, K.; Pindus, N.; Levy, D.; Tannehill, T.; Hillabrant, W. Tribal Food Assistance: A Comparison of the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Monat, J.P.; Gannon, T.F. What Is Systems Thinking? A Review of Selected Literature Plus Recommendations. Am. J. Syst. Sci. 2015, 2015, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholder Type | Navajo Nation | KBIC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-time 1 WIC participants | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| New 2 WIC participants | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Former WIC participants | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| WIC-eligible non-participants | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| WIC staff | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Tribal health administrators | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| WIC food vendors | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 15 | 16 | 31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estradé, M.; Alarcon Basurto, S.G.; McCarter, A.; Gittelsohn, J.; Igusa, T.; Zhu, S.; Poirier, L.; Gross, S.; Pardilla, M.; Rojo, M.; et al. A Systems Approach to Identify Factors Influencing Participation in Two Tribally-Administered WIC Programs. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051210

Estradé M, Alarcon Basurto SG, McCarter A, Gittelsohn J, Igusa T, Zhu S, Poirier L, Gross S, Pardilla M, Rojo M, et al. A Systems Approach to Identify Factors Influencing Participation in Two Tribally-Administered WIC Programs. Nutrients. 2023; 15(5):1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051210

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstradé, Michelle, Samantha Grace Alarcon Basurto, Abbegayle McCarter, Joel Gittelsohn, Takeru Igusa, Siyao Zhu, Lisa Poirier, Susan Gross, Marla Pardilla, Martha Rojo, and et al. 2023. "A Systems Approach to Identify Factors Influencing Participation in Two Tribally-Administered WIC Programs" Nutrients 15, no. 5: 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051210