A Qualitative Process Evaluation of Participant Experiences in a Feasibility Randomised Controlled Trial to Reduce Indulgent Foods and Beverages

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Say No Study

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Themes Identified

3.3. Theme 1: The Definition of an Indulgence

“Cakes, chocolate. Chocolate, I didn’t go through as much. Yes, I’ve actually cut back on chocolate. But things like the pastries and the muffins and the large coffees, so. And ice creams have been on the radar a bit as well.” Male, 50 years.

“So, but then I was wondering about things like, so after I’ve played some tennis on the weekend, we went to somebody’s place afterwards for a kind of afternoon tea. And so having that extra slice of fruit bread with nice soft cheese on it. And really, you’re not hungry. So, I suppose that’s a good, an easy part of the definition. If you’re really not hungry and you’re just having something for the taste of it, all that.” Female, 61 years.

“Usually anything processed that I know isn’t necessarily positive calories. So, anything empty calories or sugary or overly processed, I would consider an indulgence, particularly if it’s not even disguising itself as healthy food, so chocolate bars, soft drinks, things like that.” Male, 41 years.

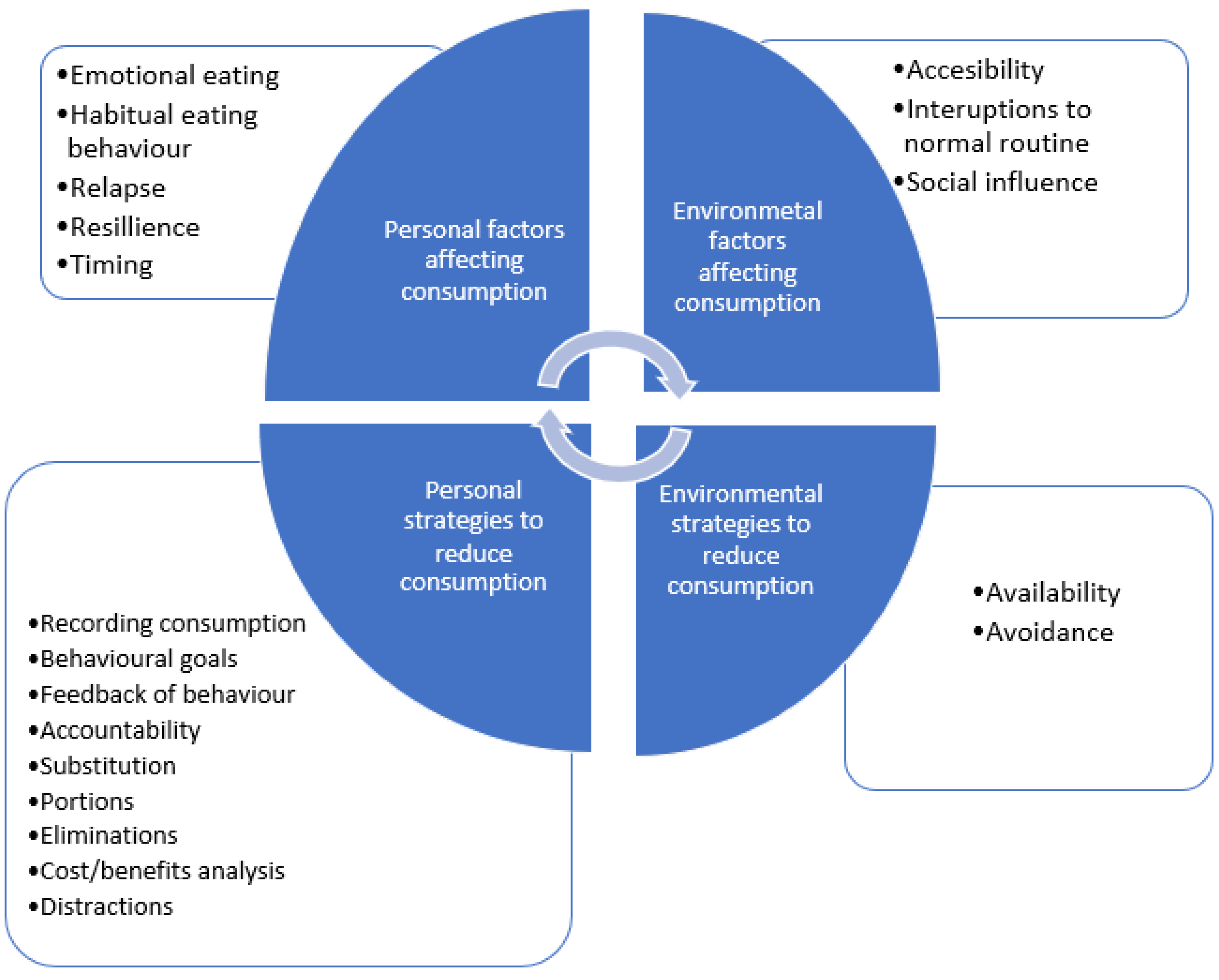

3.4. Theme 2: Factors Affecting Consumption

3.5. Accessibility of Food and Beverages

“Well, when I go to a lot of cafes, you know, like even in the window, it’s just a carb window; I just look at it and go, “Carb, carb, carb, sugar, carb, carb, carb, sugar”. That’s it, that is the window.” Female, 55 years.

“I’ve got an Aldi on the corner from work and that’s been really helpful because Aldi is very limited in what they keep, but they tend to keep seasonal things … and that’s where I go, and I can buy two salmon pieces at Aldi, which are the right size for us to eat, whereas at Woolworths I’ve got to buy one and a half times what we can eat, and then it goes in the fridge and then I’ll pick at it after tea and the next morning. And I really find it hard to throw anything in the bin.” Female, 60 years.

“We’re lucky enough to get food offered a few times a week and sometimes it’s pastries, sometimes it’s left-over sandwiches or salads and you know, I really know that I’ve already had my lunch; there’s no reason to want it but because it’s there and because somebody else has prepared it and of course it’s free, it’s really hard to resist.” Female, 54 years.

3.6. Emotional Eating

“Yeah, so I find, you know, I go to bed and I’m trying not to be stressed but as soon as I start thinking about planning for the rest of the week, I think that’s when it gets stressful which is when I’m more likely to eat the packet of Twisties or the ice cream and the stuff before I go to sleep.” Female, 54 years.

Another participant spoke about stressing over their weight encouraging more eating: “It’s just, I want to go down to 70 kilo at least, because now it’s over the top. And the more I stress the more I eat, and now I’m thinking, what’s going on?” Female, 61 years.

3.7. Influence of Others

“And it was like, normally once or twice a week, on the weekends I treat myself. I like cheese, but my daughter keeps telling me, “Mum, you’re only allowed two slices”. [laughs] “Now go away”. Or [pause], and I find it hard, and I love blue cheese.” Female, 60 years.

“I actually got my flatmate onto it as well. I just said well we’re going to go, and this is what we’re going to do for the next eight weeks. And they lost 10.5 kilos.” Male, 33 years.

“Really, the house is very healthy because of the young kids; they don’t get chocolate, they don’t get McDonald’s, so as long as I’m home I’m like, “Yeah, okay,” I won’t drink any beer, so I haven’t been drinking beer, so I haven’t been socialising. It’s pretty healthy. A bit boring.” Male, 42 years.

“And it’s interesting, like, you have, kind of find yourself in certain situations where it’s expected. Like, it’ll be, I was at work the other day and there was someone’s birthday, so we’re having cakes and stuff. And I just got handed a plateful of cake. And it would have, kind of one of those situations where it would have been rude not to have, to have said, oh, actually I don’t want it, and passed it along. Whereas the, one of my colleagues had already snuck out of the room at that point. And I thought, oh, I should have just snuck out of the room and that way I wouldn’t have had to coped with it all. But yeah. So I ate it.” Female, 43 years.

3.8. Habitual Eating Behaviour

“… What I realised it’s not so much the food, it’s just a pattern of eating, and a pattern of indulgence and pattern of, you know that you just …. It’s old habits, yeah. And it’s just choosing to ignore this, because you know, once you know that you shouldn’t be eating something, or you should be eating less of something, you can’t un-know it. You just choose to ignore it.” Female, 59 years.

3.9. Additional Factors Affecting Consumption

3.10. Theme 3: Self-Regulation

“I found the first part of it where we filled out the diary for a week really helpful because it made me aware exactly what I was eating. Sometimes it’s a bit hard to just keep tabs of all the snacks and you know, over at the …. School, we have our morning tea, lunch, afternoon tea but there’ll be lots of food left over from functions and stuff and so you think if you have a small square of a pastry or a cake that, you know, if you’re not writing it down, it’s easy to forget that you’ve actually had a small piece.” Female, 54 years.

“Well, I’ve obviously been reasonably good, because I’ve lost nearly four kilos. It’s made me more mindful. It made me a little bit more accountable and more mindful.” Female, 54 years.

“I was, the first weeks I was better. I was thinking more. But then I think after, as the week goes, and because I don’t have anything to report, I guess I should be feeling that, okay, accountable. Like, in a way, it’s what I need to. Like, maybe get weighed, like every week. Or once a week.” Female, 58 years.

3.11. Theme 4: Strategies to Reduce Consumption

“We don’t have the snacks in our rooms; we just have trays. The other rooms have a lot of snacks, so I don’t go to the other rooms.” Female, 42 years.

“Like, even, like, I don’t buy Magnums by the box and keep them in the fridge. And so, then I have to go to the service station, where they’re three times the price. And so you think about how much it’s going to cost you.” Female, 68 years.

“But it’s like you don’t need three big pieces of toast. Just try and have one or one and a half and just try and cut back.” Female, 55 years.

“I’ve had a banana, like I would have a banana instead of a chocolate, or I had a cup of this fantastic tea I just discovered, instead of the sweet biscuits and a cup of tea at night, with my mum, I’ve even got my mum onto this different tea. And it’s just a herbal tea, so no milk, … but because you’ve had this herbal tea it doesn’t set up the attachment to the biscuits …” Female, 58 years.

“I sometimes compare that I drive my bike from my home to here; it is 25 k, it is one hour of pedalling. I just spend 700 calories, and one Tim Tam has 100 calories.” Male, 44 years.

“Twofold things occurred, this study and also the fact that I’m now saving frantically for a deposit on a house. So, basically, any time I’ve felt like something, in the last week particularly, I’ve just gone, “No, instead of spending that and eating it, oh great I’ve said ‘No’, at the same time I’m moving the money into my savings account. So, I would literally stand in 7-Eleven, holding the bag of chips, or holding whatever I was saying “No” to, putting them back on the shelf and transferring the money straight away. So, I’ve spent the money but it’s just gone somewhere else and not in my mouth.” Female, 58 years.

3.12. Theme 5: Negative Effects of Trying to Reduce Consumption

“Yes, the word “denial” is not very nice! If I deny myself something it turns up somewhere else and worse.” Female, 58 years.

“And towards the end, so that was the first six weeks it was quite a battle, and then, in the last two weeks, I’ve had, something’s shifted, and I’ve actually made better choices. Even after I’ve said “No” to something really bad, I’ve then immediately chosen something good.” Female, 58 years.

“Yeah, so I thought I should probably, “I’m doing this study, I shouldn’t be having that. Really, I should not be having that. The purpose of the study is not having the indulgences”, so then I was getting a bit, “No, I’m not going to be a good student for them.” Female, 58 years.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bes-Rastrollo, M.; van Dam, R.M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Li, T.Y.; Sampson, L.L.; Hu, F.B. Prospective study of dietary energy density and weight gain in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prentice, A.M.; Jebb, S.A. Fast foods, energy density and obesity: A possible mechanistic link. Obes. Rev. 2003, 4, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hill, J.O.; Peters, J. Environmental Contributions to the Obesity Epidemic. Science 1998, 280, 1371–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.; Caterson, I.; Seidell, J.; James, W. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, C.; Keast, D.; Fulgoni Iii, V.; Nicklas, T. Food sources of energy and nutrients among adults in the US: NHANES 2003–2006. Nutrients 2012, 4, 2097–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results–Foods and Nutrients, 2011–12; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Zhong, G.-C.; Gu, H.-T.; Peng, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Hu, T.-Y.; Jing, F.-C.; Hao, F.-B. Association of ultra-processed food consumption with cardiovascular mortality in the US population: Long-term results from a large prospective multicenter study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, U.; McCann, S.E.; Zirpoli, G.; Gong, Z.; Lin, Y.; Hong, C.-C.; Ciupak, G.; Pawlish, K.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Bandera, E.V. Intake of energy-dense foods, fast foods, sugary drinks, and breast cancer risk in African American and European American women. Nutr. Cancer 2014, 66, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Discretionary Foods Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.007~2011-12~Main%20Features~Discretionary%20foods~700 (accessed on 16 July 2016).

- Adriaanse, M.A.; de Ridder, D.T.D.; de Wit, J.B.F. Finding the Critical Cue: Implementation Intentions to Change One’s Diet Work Best When Tailored to Personally Relevant Reasons for Unhealthy Eating. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, A.A.C.; Adriaanse, M.A.; Evers, C.; de Ridder, D.T.D. The power of habits: Unhealthy snacking behaviour is primarily predicted by habit strength. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüz, B.; Schüz, N.; Ferguson, S.G. It’s the power of food: Individual differences in food cue responsiveness and snacking in everyday life. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madigan, C.D.; Hill, A.J.; Hendy, C.; Burk, J.; Caterson, I.D. ‘Say no’: A feasibility trial of a brief intervention to reduce instances of indulgent energy-intake episodes. Clin. Obes. 2018, 8, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh Roy, P.; Jones, K.K.; Martyn-Nemeth, P.; Zenk, S.N. Contextual correlates of energy-dense snack food and sweetened beverage intake across the day in African American women: An application of ecological momentary assessment. Appetite 2019, 132, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachat, C.; Nago, E.; Verstraeten, R.; Roberfroid, D.; Van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, S.N.; Horoi, I.; McDonald, A.; Corte, C.; Riley, B.; Odoms-Young, A.M. Ecological momentary assessment of environmental and personal factors and snack food intake in African American women. Appetite 2014, 83, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fong, M.; Li, A.; Hill, A.J.; Cunich, M.; Skilton, M.; Madigan, C.D.; Caterson, I.D. Mood and appetite: Their relationship with discretionary and total daily energy intake. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 207, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devonport, T.J.; Nicholls, W.; Fullerton, C. A systematic review of the association between emotions and eating behaviour in normal and overweight adult populations. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Conner, M.; Clancy, F.; Moss, R.; Wilding, S.; Bristow, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and eating behaviours in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021, 16, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelhans, B.M.; French, S.A.; Pagoto, S.L.; Sherwood, N.E. Managing temptation in obesity treatment: A neurobehavioral model of intervention strategies. Appetite 2016, 96, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grieger, J.; Wycherley, T.; Johnson, B.; Golley, R. Discrete strategies to reduce intake of discretionary food choices: A scoping review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrade, J.; Khalil, M.; Dickson, J.; May, J.; Kavanagh, D. Functional Imagery Training to reduce snacking: Testing a novel motivational intervention based on Elaborated Intrusion theory. Appetite 2016, 100, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeven, A.A.C.; Adriaanse, M.A.; de Vet, E.; Fennis, B.M.; de Ridder, D.T.D. Identifying the ‘if’ for ‘if-then’ plans: Combining implementation intentions with cue-monitoring targeting unhealthy snacking behaviour. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 1476–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatzemeier, J.; Price, M.; LWilkinson, L.; Lee, M. Understanding everyday strategies used to manage indulgent food consumption: A mixed-methods design. Appetite 2019, 136, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanfer, F.H. Self-monitoring: Methodological limitations and clinical applications. J. Consult. Clin. Appl. 1970, 35, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; McNaughton Nicholls, C.; Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pettigrew, S.; Talati, Z.; Pratt, I.S. Health communication implications of the perceived meanings of terms used to denote unhealthy foods. BMC Obes. 2017, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roe, L.S.; Rolls, B.J. Which strategies to manage problem foods were related to weight loss in a randomized clinical trial? Appetite 2020, 151, 104687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayn, M.; Knäuper, B. Emotional Eating and Weight in Adults: A Review. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, E.M.; Butryn, M.L.; Manasse, S.M.; Crosby, R.D.; Goldstein, S.P.; Wyckoff, E.P.; Thomas, J.G. Acceptance-based versus standard behavioral treatment for obesity: Results from the mind your health randomized controlled trial. Obesity 2016, 24, 2050–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Juarascio, A.S.; Parker, M.N.; Manasse, S.M.; Barney, J.L.; Wyckoff, E.P.; Dochat, C. An exploratory component analysis of emotion regulation strategies for improving emotion regulation and emotional eating. Appetite 2020, 150, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Richards, R.; Lally, P.; Rebar, A.; Thwaite, T.; Beeken, R.J. Breaking habits or breaking habitual behaviours? Old habits as a neglected factor in weight loss maintenance. Appetite 2021, 162, 105183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, L.M.; Sharkey, T.; Whatnall, M.C.; Williams, R.L.; Bezzina, A.; Aguiar, E.J.; Collins, C.E.; Hutchesson, M.J. Effectiveness of Interventions and Behaviour Change Techniques for Improving Dietary Intake in Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Nutrients 2019, 11, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michie, S.; Abraham, C.; Whittington, C.; McAteer, J.; Gupta, S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: A meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahern, A.; Boyland, E.; Jebb, S.; Cohn, S. Participants’ explanatory model of being overweight and their experiences of 2 weight loss interventions. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madigan, C.D.; Daley, A.; Lewis, A.; Aveyard, P.; Jolly, K. Is self-weighing an effective tool for weight loss: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hill, J.O. Can a small-changes approach help address the obesity epidemic? A report of the Joint Task Force of the American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and International Food Information Council. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Graham, H.E.; Madigan, C.D.; Daley, A.J. Is a small change approach for weight management effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Th | Subthemes | Example Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| What is an indulgence? A description of foods and drinks that are considered indulgences. | Food groups A specific food or group of foods that is considered an indulgence. | The, and probably my other indulgence, well it’s not an indulgence it’s a, it’s an addiction, is the, the dreaded sugar. Male, 67 years. |

| Excess food Too much food is considered an indulgence. | For me, I think indulgence is when I eat too much of something, like I like eating pork, and sometimes, when I get good pork, I could eat more. And so I think if you eat something in a moderate quantity, even if it is like a chocolate or sugary thing, if you eat a little bit, that’s nothing. But if you overdo it, that’s bad. Female, 46 years. | |

| Nutritional value Related to perceived healthiness of foods. | For me, I don’t eat indulgences, so, or I don’t indulge. So what I’ve used is anything where there is possibly a healthier option to take. Male, 44 years. | |

| Factors affecting consumption A factor that is reported to affect consumption but is not a specific strategy that people use to reduce consumption. | Emotional eating The consumption of food/drink for reasons other than hunger. | Yeah. So sometimes it would be, it was crap for me if I stay late at work. And I had, and there’s a slight emotional tag for that. So when I realize oh, blast, I’m the last one here, and so there’s a kind of a sadness with that, because I don’t have a family to race off to any more, kind of thing. And then that slightly grumpy, resentful, oh. And then if I feel hungry, as I often will, because it’s getting late. It might be 6:30, getting on to 7 o’clock, I will just think of the vending machine upstairs that has got some chips in it. Crisps, you know. And so I would often fall for that, succumb to that. Female, 61 years. |

| Interruptions to normal routine When an interruption to perceived normal routine results in consumption changing. | It’s a little bit hard to get into a routine when my routine gets interrupted with the in-laws here for six months … ah, six weeks … Yeah. So I think those type of interruptions just doesn’t help because I can’t really do my usual walk over the bridge because I need to be home straight away so we can spend time together. I could be a little bit stricter but it’s like “No, they’re on holidays. I’m going to be on holidays.” Female, 39 years. | |

| Accessibility How easily available indulgences are. | Yeah. To an extent, I probably found it a bit harder in the domestic situation at home, especially when not much was happening. So I was having a cup and grabbing some biscuits. Instead of two I might have three or four, kind of thing. So, yeah. Male, 50 years. | |

| Influence of others How others may influence the participants’ consumption of indulgences. | Yeah, and also living with someone, it’s hard …I live with a man who rewards himself with food, who makes himself feel better, makes himself feel happy with food, and so there are times when you go, “No, I’m not going to do that”. Then other times you’re going, “Looks really nice.” Female, 59 years. | |

| Yeah. What’s very useful to me in that regard is that I’m very, very hands on with my grandchildren. And their parents and we are very strict with them about the clarity around what is a sometimes food and what is a, indulgence. And so, of course, if you’re imposing those standards, it makes you think a bit more about your own behaviour, which is helpful. Female, 67 years. | ||

| Habitual eating behaviour Something that you do often and regularly. | I don’t know. The habitual thing is to always say, for people like me is to always say, “Yes.” Female, 58 years. | |

| Relapse An occasion when after successfully reducing indulgences, they are then consumed. | Yeah, and I don’t know, like I can go really well for weeks and weeks and weeks, and I know one little chink and then that’s it. Like this week I ate that cake; every day there was something. Like after I’d had that, normally if Alex had said, “Do you want pasta for tea tonight,” I would have said, “No,” but I thought, “Oh, I’ve had a cake and I’d like some pasta.” Female, 60 years. | |

| Resilience Continuing to reduce consumption in the face of adversity. | But I feel I’ve got a really strong resolve now and I think that’s because I really did appreciate and see the shift in, in cravings. Female, 55 years. | |

| Timing Reporting that there are specific times for consumption. | So, you know, I would like to try to eat earlier during the day because I know I’m going to be up later and continuing to lose that energy but it doesn’t work that way. I’m in such a rush in the morning, I eat very little and then as I get home and are at home, that’s when I tend to eat because I’m really hungry by then. Female, 54 years. | |

| Self-regulation of eating The act of controlling one’s behaviour compared with a goal. | Mindfulness Consciously aware of what they are consuming. | I found I was conscious of the program and saying no and would find for the most part my diet and what I chose to eat during the day would never, I wouldn’t feel I was tempted by even having an indulgence, because I was always very happy to eat. Female, 58 years. |

| Recording consumption Recording or measuring their eating or drinking. | But I do enjoy my wine, so … I’m just measuring it. Female, 68 years. | |

| Behavioural goals Setting behavioural goals to reduce consumption. | I just thought to myself, “No, I’m not going to have that.” So it was, but I wouldn’t have always necessarily taken it anyway; I would have just resisted it because I know it’s not good for me. But because I was doing this study, I thought about what you’re really doing, my commitment with it, and I thought, “That’s interesting, I’m going to say no to that.” Female, 58 years. | |

| Feedback on behaviour The interpretation of feedback from others or themselves via self-monitoring. | I’ll try and just have this mental check about portion size and how much I’m eating but certainly what this program has done is made me think about the indulgences and probably more the chocolate and the sweets. Female, 55 years. | |

| Accountability The perceived obligation to be answerable to someone. | I’m saying “No” because I’m in this study and I’ve got to say “No, I’m not having it.” So I’m saying “No.” They thought that was hilarious. Yes. I had a bread roll one time and, “Oh, I’d really like that.” It was at a golf lunch, yeah. No. I’m saying no to this. Oh, would you like my bread roll? Perhaps I could take a photo first. Send it over to the other side of the table …” Female, 68 years. | |

| Strategies people use to overcome consumption A strategy or technique that people use to reduce the indulgences they consume. | Substitution Swapping an indulgence for another item that is thought of as healthier. | Other times I’ll have yoghurt and strawberries or something. So I make sure I’ve got yoghurt and strawberries. And I just have that instead of the ice cream. Female, 68 years. |

| Portions Reducing the size or number of things that are consumed. | And when we go for coffees and things, which we do once a week, twice a week probably, we try and, we share if we have something. Like yesterday it was one muffin four ways. Female, 68 years. | |

| Elimination Removal of indulgences from their diet. | Yeah well I, they’re the same most days and I would tend to think that, you know, I have me Vita Brits or me porridge or, you know me cereal of a morning which is pretty much the same and what I used to do was put a dabble of cream on it. I: Okay and you stopped that? And I just, I wouldn’t say 100% but … most of the time. Male, 67 years. | |

| Cost/benefit analysis Weighing up the benefits and costs of consuming the indulgence. | And I thought look there’s just no nutritional value in that. It’s just a bit of comfort food. Female, 55 years. | |

| Distractions Something that prevents them from focusing on consuming indulgences. | And of course, at home it’s very hard. So what I started doing is, I keep telling myself, “Okay, I’ll eat it later.” Female, 46 years. | |

| Avoidance Purposefully avoiding a situation that would result in consuming indulgences. | And I don’t go to that section in the supermarket anymore. Male, 33 years. | |

| Availability Limiting the accessibility of indulgences. | Yeah, exactly. And that’s I think just what it said there; so we sort of made a decision at home…stop buying it, because I’ll just, I just eat it all. Male, 42 years. | |

| Negative consequences of saying no Negative affect experienced when participants say no to consuming indulgences | Denial The negative feeling of not being allowed to consume an indulgence. | But it’s a lifestyle thing as well, but I don’t necessarily like not eating. I feel like I’m denying myself. I really feel like I’m denying myself all the time. Female, 60 years. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madigan, C.D.; Hill, A.J.; Caterson, I.D.; Burk, J.; Hendy, C.; Chalkley, A. A Qualitative Process Evaluation of Participant Experiences in a Feasibility Randomised Controlled Trial to Reduce Indulgent Foods and Beverages. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061389

Madigan CD, Hill AJ, Caterson ID, Burk J, Hendy C, Chalkley A. A Qualitative Process Evaluation of Participant Experiences in a Feasibility Randomised Controlled Trial to Reduce Indulgent Foods and Beverages. Nutrients. 2023; 15(6):1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061389

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadigan, Claire Deborah, Andrew J. Hill, Ian Douglas Caterson, Jessica Burk, Chelsea Hendy, and Anna Chalkley. 2023. "A Qualitative Process Evaluation of Participant Experiences in a Feasibility Randomised Controlled Trial to Reduce Indulgent Foods and Beverages" Nutrients 15, no. 6: 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061389

APA StyleMadigan, C. D., Hill, A. J., Caterson, I. D., Burk, J., Hendy, C., & Chalkley, A. (2023). A Qualitative Process Evaluation of Participant Experiences in a Feasibility Randomised Controlled Trial to Reduce Indulgent Foods and Beverages. Nutrients, 15(6), 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061389