Association between Eating Habits and Sodium Intake among Chinese University Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Demographic Characteristics

2.3.2. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices about Salt

2.3.3. Food Environment

2.3.4. Eating Habits

2.3.5. Assessment of Sodium Intakes

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of College Students in Terms of Sodium Intakes and Dietary Habits

3.2. Sodium Intake and Eating Habits among College Students

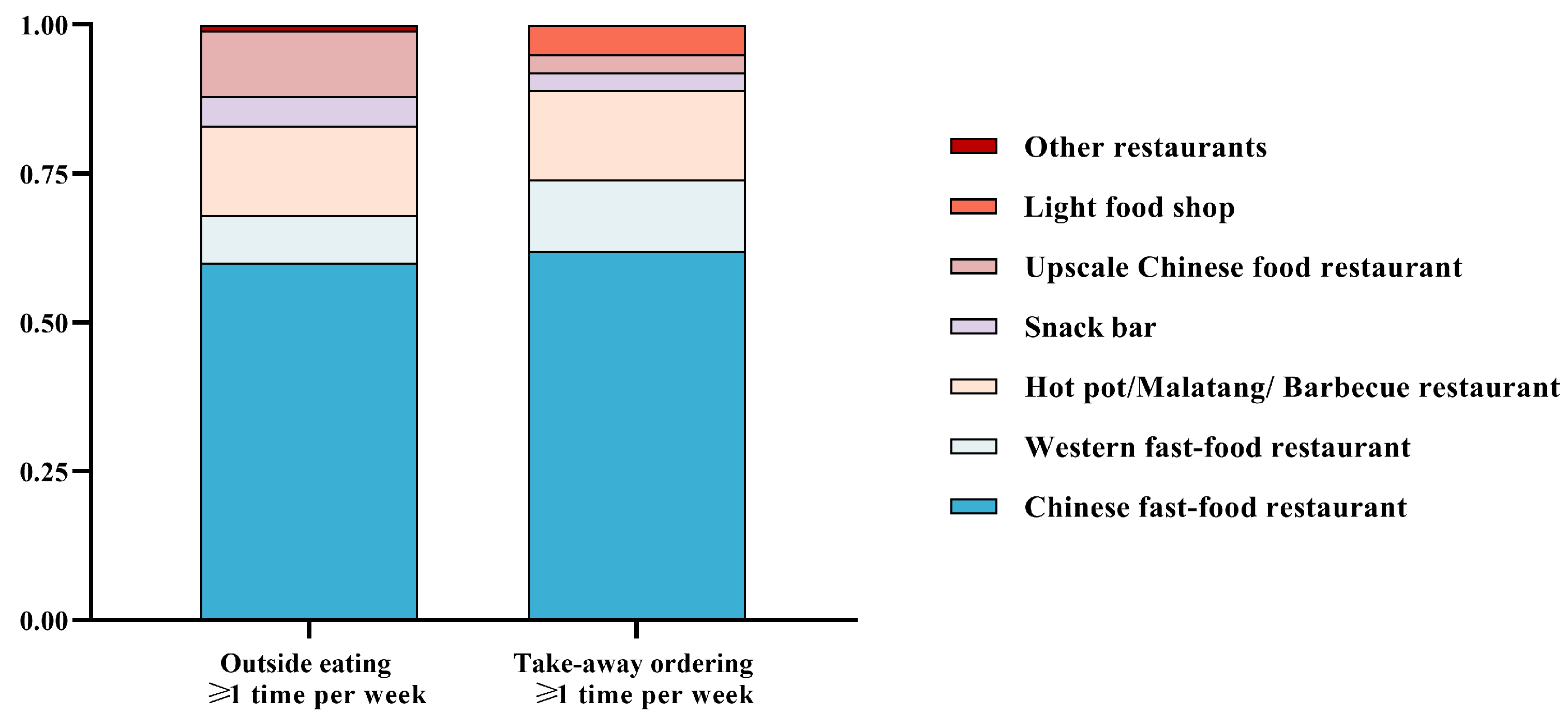

3.3. Type of Favorite Restaurants for College Students to Go out or Order Takeaway

3.4. The Association between Eating Habits and Sodium Intake among College Students

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, Y.; Joseph, J. Sodium Intake and Heart Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.J.; Yeh, T.L.; Shih, M.C.; Tu, Y.K.; Chien, K.L. Dietary Sodium Intake and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, E.M.; Cunha, L.C.C.; Dias, R.S.C.; Diniz, C.; Brito, D.J.A.; Teixeira, T.C.S.; Santos, A.M.D.; Aktdc, F. Dietary evaluation of sodium intake in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nutr. Hosp. 2023, 40, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankey, G.; Collaborators, G.D. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, J.H.; Park, C.H.; Eun, C.S.; Han, D.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Song, K.S.; Choi, B.Y.; Kim, H.J. The Associations of Dietary Intake of High Sodium and Low Zinc with Gastric Cancer Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study in Korea. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 3501–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, J.; Fahimi, S.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Ezzati, M.; Engell, R.E.; Lim, S.S.; Danaei, G.; Mozaffarian, D.; et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wojcik, M.; Koziol-Kozakowska, A. Obesity, Sodium Homeostasis, and Arterial Hypertension in Children and Adolescents. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, I. Psychoactive drug exposure during breastfeeding: A critical need for preclinical behavioral testing. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dunteman, A.N.; McKenzie, E.N.; Yang, Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.Y. Compendium of sodium reduction strategies in foods: A scoping review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1300–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Appel, L.J.; Okuda, N.; Brown, I.J.; Chan, Q.; Zhao, L.; Ueshima, H.; Kesteloot, H.; Miura, K.; Curb, J.D.; et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: The INTERMAP study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magriplis, E.; Farajian, P.; Pounis, G.D.; Risvas, G.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Zampelas, A. High sodium intake of children through ‘hidden’ food sources and its association with the Mediterranean diet: The GRECO study. J. Hypertens. 2011, 29, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allison, A.; Fouladkhah, A. Adoptable Interventions, Human Health, and Food Safety Considerations for Reducing Sodium Content of Processed Food Products. Foods 2018, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Havas, S.; Dickinson, B.D.; Wilson, M. The urgent need to reduce sodium consumption. JAMA 2007, 298, 1439–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Popkin, B.M. Dietary Potassium Intake Remains Low and Sodium Intake Remains High, and Most Sodium is Derived from Home Food Preparation for Chinese Adults, 1991–2015 Trends. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levings, J.L.; Cogswell, M.E.; Gunn, J.P. Are reductions in population sodium intake achievable? Nutrients 2014, 6, 4354–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taher, A.K.; Evans, N.; Evans, C.E. The cross-sectional relationships between consumption of takeaway food, eating meals outside the home and diet quality in British adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffe, L.; Rushton, S.; White, M.; Adamson, A.; Adams, J. Relationship between mean daily energy intake and frequency of consumption of out-of-home meals in the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Laska, M.N.; Story, M. Young adults and eating away from home: Associations with dietary intake patterns and weight status differ by choice of restaurant. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hu, P.; Wu, T.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; Zeng, H.; Shi, Z.M.; Sharma, M.; Xun, L.; Zhao, Y. Association between Eating Out and Socio-Demographic Factors of University Students in Chongqing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luo, M.; Wang, Q.; Yang, S.; Jia, P. Changes in patterns of take-away food ordering among youths before and after COVID-19 lockdown in China: The COVID-19 Impact on Lifestyle Change Survey (COINLICS). Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachat, C.; Nago, E.; Verstraeten, R.; Roberfroid, D.; Van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y.J.; Jung, H.J.; Paik, H.Y.; Song, Y.J. The nutrition contribution of dietary supplements on total nutrient intake in children and adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G. Socio-economic differences in takeaway food consumption among adults. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunford, E.; Webster, J.; Barzi, F.; Neal, B. Nutrient content of products served by leading Australian fast food chains. Appetite 2010, 55, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworowska, A.; Blackham, T.; Davies, I.G.; Stevenson, L. Nutritional challenges and health implications of takeaway and fast food. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Wu, L.; Hu, W. Nutritional quality and consumer health perception of online delivery food in the context of China. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworowska, A.; Blackham, T.; Stevenson, L.; Davies, I.G. Determination of salt content in hot takeaway meals in the United Kingdom. Appetite 2012, 59, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Perez, N.; Telleria-Aramburu, N.; Insua, P.; Hernandez, I.; Telletxea, S.; Ansotegui, L.; Rebato, E.; Basabe, N.; de Pancorbo, M.M.; Rocandio, A.; et al. On-campus food purchase behaviors, choice determinants, and opinions on food availability in a Spanish university community. Nutrition 2022, 103–104, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, G.G.; Longo, L.M.; Martin, J.L. Social media and college student risk behaviors: A mini-review. Addict. Behav. 2017, 65, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwahori, T.; Ueshima, H.; Ohgami, N.; Yamashita, H.; Miyagawa, N.; Kondo, K.; Torii, S.; Yoshita, K.; Shiga, T.; Ohkubo, T.; et al. Effectiveness of a Self-monitoring Device for Urinary Sodium-to-Potassium Ratio on Dietary Improvement in Free-Living Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, P.; Chen, Z.; Yin, L.; Peng, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhu, X.; He, X.; et al. Salt intake assessed by spot urine on physical examination in Hunan, China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 28, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chu, H.; Peng, K.; Yin, X.; Huang, L.; Wu, Y.; Pearson, S.A.; Li, N.; Elliott, P.; Yan, L.L.; et al. Factors Associated With the Use of a Salt Substitute in Rural China. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2137745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, M.; Ma, X.; Zhao, X.; Jia, M.; Li, J.; Yang, M.; Ru, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, N.; Zhu, S. Multiplicity and complexity of food environment in China: Full-scale field census of food outlets in a typical district. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Kim, H.C.; Oh, S.M.; Choi, D.P.; Cho, J.; Suh, I. Factors Associated with a Low-sodium Diet: The Fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Epidemiol. Health 2013, 35, e2013005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byrd, K.; Almanza, B.; Ghiselli, R.F.; Behnke, C.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. Reported Action to Decrease Sodium Intake Is Associated with Dining Out Frequency and Use of Menu Nutrition Information among US Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Seto, E.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.C. Development and evaluation of a food environment survey in three urban environments of Kunming, China. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, L.-S.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Bao, Y.; Cai, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Chu, S.; Feng, Y. 2018 Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension-A report of the revision committee of Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 182–245. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K.; He, Y.; Fang, Y.; Lian, Y. Dietary Sodium Intake and Food Sources Among Chinese Adults: Data from the CNNHS 2010–2012. Nutrients 2020, 12, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.G.; Wang, Z.H.; Du, W.W.; Su, C.; Jiang, H.R.; Huang, F.F.; Jia, X.F.; Ouyang, Y.F.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Dietary sodium intake of adult residents in 15 provinces of China in 2015. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 53, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, K. Secular trends in salt and soy sauce intake among Chinese adults, 1997–2011. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 69, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, N.; Li, Y.; Tan, M.; Zhang, P.; He, F.J. Sodium content of restaurant dishes in China: A cross-sectional survey. Nutr. J. 2022, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, F.; Ambak, R.; Man, C.S.; Zaki, N.A.M.; Ahmad, M.H.; Aziz, N.S.A.; Baharuddin, A.; Salleh, R.; Aris, T. Factors Associated with High Sodium Intake Assessed from 24-hour Urinary Excretion and the Potential Effect of Energy Intake. J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 2019, 6781597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ding, G. Validation of 4 Estimating Methods to Evaluate 24-h Urinary Sodium Excretion: Summer and Winter Seasons for College Students in China. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Bo, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, L. Validation and Assessment of Three Methods to Estimate 24-h Urinary Sodium Excretion from Spot Urine Samples in Chinese Adults. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, B.; Rafferty, A.P.; Lyon-Callo, S.; Fussman, C.; Imes, G. Fast-food consumption and obesity among Michigan adults. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011, 8, A71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, C.M.; Hughes, J.P.; Cogswell, M.E.; Burt, V.L.; Lacher, D.A.; Lavoie, D.J.; Rabinowitz, D.J.; Johnson, C.L.; Pirkle, J.L. Urine sodium excretion increased slightly among U.S. adults between 1988 and 2010. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mizehoun-Adissoda, C.; Houinato, D.; Houehanou, C.; Chianea, T.; Dalmay, F.; Bigot, A.; Aboyans, V.; Preux, P.M.; Bovet, P.; Desport, J.C. Dietary sodium and potassium intakes: Data from urban and rural areas. Nutrition 2017, 33, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, S.; Bista, B.; Yadav, B.K.; Gynawali, P.; Poudyal, A.; Jha, A.K.; Dhimal, M. Estimation of mean population salt intakes using spot urine samples and associations with body mass index, hypertension, raised blood sugar and hypercholesterolemia: Findings from STEPS Survey 2019, Nepal. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, H.; Kamal, N.F.; Yahya, H.M.; Shahar, S. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) of Malay Elderly on Salt Intake and Its Relationship With Blood Pressure. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 559071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharudin, A.; Ambak, R.; Othman, F.; Michael, V.; Cheong, S.M.; Mohd Zaki, N.A.; Abdul Aziz, N.S.; Mohd Sallehuddin, S.; Ganapathy, S.S.; Palaniveloo, L.; et al. Knowledge, attitude and behaviour on salt intake and its association with hypertension in the Malaysian population: Findings from MyCoSS (Malaysian Community Salt Survey). J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Nie, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Luo, R.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; He, F.J. Salt-Related Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors and Their Relationship with 24-H Urinary Sodium Excretion in Chinese Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; Goffe, L.; Brown, T.; Lake, A.A.; Summerbell, C.; White, M.; Wrieden, W.; Adamson, A.J. Frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and take-away meals at home: Cross-sectional analysis of the UK national diet and nutrition survey, waves 1–4 (2008-12). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; He, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zeng, X.; et al. Association between Take-Out Food Consumption and Obesity among Chinese University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lattie, E.G.; Adkins, E.C.; Winquist, N.; Stiles-Shields, C.; Wafford, Q.E.; Graham, A.K. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression, Anxiety, and Enhancement of Psychological Well-Being Among College Students: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mochrie, K.D.; Whited, M.C.; Cellucci, T.; Freeman, T.; Corson, A.T. ADHD, depression, and substance abuse risk among beginning college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, K.B.; Ding, M.; Owensby, J.K.; Zizza, C.A. Impulsivity and Fast-Food Consumption: A Cross-Sectional Study among Working Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansstein, F.V.; Hong, Y.; Di, C. The relationship between new media exposure and fast food consumption among Chinese children and adolescents in school: A rural-urban comparison. Glob. Health Promot. 2017, 24, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, Q.; Luo, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Sun, M.; Xi, Y.; Yong, C.; Xiang, C.; Lin, Q. Association between Emotional Eating, Depressive Symptoms and Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Symptoms in College Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Hunan. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A.W.; Rydell, S.A.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Laska, M.N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Yoga’s potential for promoting healthy eating and physical activity behaviors among young adults: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ling, J.; Zahry, N.R. Relationships among perceived stress, emotional eating, and dietary intake in college students: Eating self-regulation as a mediator. Appetite 2021, 163, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.; Liu, H.; Yang, Q.; Luo, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Sun, M.; Xi, Y.; Xiang, C.; Lin, Q. The Relationship between Restrained Eating, Body Image, and Dietary Intake among University Students in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.; Luo, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Wang, W.; Guo, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Eating Out-of-Home in Adult Residents in Shanghai and the Nutritional Differences among Dining Places. Nutrients 2018, 10, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Llanaj, E.; Adany, R.; Lachat, C.; D’Haese, M. Examining food intake and eating out of home patterns among university students. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, H.; Xue, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Franco, O.H.; Li, Y.; Heianza, Y.; Manson, J.E.; Qi, L. Adding salt to foods and hazard of premature mortality. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2878–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quader, Z.S.; Zhao, L.; Harnack, L.J.; Gardner, C.D.; Shikany, J.M.; Steffen, L.M.; Gillespie, C.; Moshfegh, A.; Cogswell, M.E. Self-Reported Measures of Discretionary Salt Use Accurately Estimated Sodium Intake Overall but not in Certain Subgroups of US Adults from 3 Geographic Regions in the Salt Sources Study. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, J.; Edwards, P.; Shankar, B.; Dangour, A.D. Fewer adults add salt at the table after initiation of a national salt campaign in the UK: A repeated cross-sectional analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nilius, B.; Appendino, G. Spices: The savory and beneficial science of pungency. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 164, 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Qi, L.; Yu, C.; Yang, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bian, Z.; Sun, D.; Du, J.; Ge, P.; et al. Consumption of spicy foods and total and cause specific mortality: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2015, 351, h3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wen, Q.; Wei, Y.; Du, H.; Lv, J.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Z.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, L.; et al. Characteristics of spicy food consumption and its relation to lifestyle behaviours: Results from 0.5 million adults. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.; Saif, Z.; Faris, M.A.; Levine, M.P. The relationship between risk of eating disorders, age, gender and body mass index in medical students: A meta-regression. Eat. Weight. Disord. EWD 2019, 24, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhashemi, M.; Mayo, W.; Alshaghel, M.M.; Brimo Alsaman, M.Z.; Haj Kassem, L. Prevalence of obesity and its association with fast-food consumption and physical activity: A cross-sectional study and review of medical students’ obesity rate. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 79, 104007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlJaber, M.I.; Alwehaibi, A.I.; Algaeed, H.A.; Arafah, A.M.; Binsebayel, O.A. Effect of academic stressors on eating habits among medical students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, M.H.; Hart, L.C.; Manning-Courtney, P.; Murray, D.S.; Bing, N.M.; Summer, S. Food variety as a predictor of nutritional status among children with autism. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Chinese fast-food restaurant | Chain or individually managed Chinese restaurants offer a limited range of Chinese cuisine, including fried rice, noodles, rice, and much more. |

| Western fast-food restaurant | Restaurants mainly provide hamburgers, pizza, fried chicken, and much more, including KFC, and McDonalds. |

| Upscale Chinese food restaurant | The restaurants offer diversified Chinese diets as well as a la carte service, with seating for over 75. |

| Hot pot/Malatang/barbecue restaurant | The restaurants offer spicy dishes such as a hot pot or spicy hotpot or food baked with special seasonings. |

| Snack Bar | The stores specialize in pickled fruits, cookies, pastries, and beverage much more. |

| Light Food restaurant | The restaurants mainly sell low-salt, fat, and oil-light meal sets. |

| Other restaurants | The restaurants offer foods, not from China, such as Korean and Japanese foods. |

| Variables | Total 585 (100.0) | High Sodium Intake 295 (50.4) | p | Outside Eating # | p | Takeaway Ordering # | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1 Time per Week | ≥1 Time per Week | ||||||

| 507 (89.7) | 174 (30.9) | ||||||

| Age | 19.06 ± 1.45 | 19.13 ± 1.36 | 0.863 | 19.05 ± 1.45 | 0.151 | 19.20 ± 1.42 | 0.505 |

| Sex | 0.012 | 0.041 | 0.148 | ||||

| Male | 260 (44.4) | 116 (44.6) | 217 (86.8) | 70 (27.8) | |||

| Female | 325 (55.6) | 179 (55.1) | 290 (51.3) | 104 (33.4) | |||

| Ethic | 0.381 | 0.980 | 0.314 | ||||

| Han | 524 (89.6) | 261 (49.8) | 454 (89.7) | 160 (31.6) | |||

| other | 61 (10.4) | 34 (55.7) | 53 (89.9) | 14 (25.0) | |||

| Major | 0.682 | 0.067 | 0.004 | ||||

| Medicine | 247 (42.2) | 127 (51.4) | 221 (92.5) | 89 (37.4) | |||

| Other | 338 (57.8) | 168 (49.7) | 286 (87.7) | 85 (26.2) | |||

| Grade | 0.737 | 0.453 | 0.038 | ||||

| Freshman | 303 (51.8) | 146 (47.6) | 266 (90.8) | 80 (27.4) | |||

| Sophomore | 108 (18.5) | 60 (52.8) | 95 (91.3) | 37 (36.3) | |||

| Junior | 106 (18.1) | 56 (52.8) | 89 (85.6) | 28 (27.5) | |||

| Senior year and above | 68 (11.6) | 36 (50.4) | 57 (89.1) | 29 (43.3) | |||

| Pocket money | 0.419 | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤1000 RMB | 107 (18.3) | 56 (52.3) | 87 (84.5) | 29 (28.7) | |||

| 1001~1500 RMB | 234 (40.0) | 111 (47.4) | 192 (86.1) | 41 (18.2) | |||

| 1501~2000 RMB | 173 (29.6) | 95 (54.9) | 164 (96.5) | 67 (40.1) | |||

| >2000 RMB | 71 (12.1) | 33 (46.5) | 64 (92.8) | 37 (52.9) | |||

| Self-reported BMI (kg/m2) * | 0.743 | 0.780 | 0.195 | ||||

| Underweight | 97 (16.6) | 51 (52.6) | 86 (90.5) | 28 (29.5) | |||

| Normal | 402 (68.4) | 198 (49.3) | 348 (90.2) | 125 (32.6) | |||

| Overweight | 75 (12.8) | 39 (52.0) | 63 (86.3) | 16 (21.6) | |||

| Obesity | 11 (1.9) | 7 (63.6) | 10 (90.9) | 5 (45.5) | |||

| Salt-Related Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviors Status | |||||||

| Salt-related knowledge | 0.976 | 0.550 | 0.041 | ||||

| Low | 155 (26.5) | 78 (50.3) | 132 (91.0) | 35 (24.1) | |||

| High | 430 (73.5) | 217 (50.5) | 375 (89.3) | 139 (33.3) | |||

| Salt-related attitude | 0.864 | 0.674 | 0.203 | ||||

| Low | 238 (40.7) | 119 (50.0) | 204 (89.1) | 77 (33.9) | |||

| High | 347 (59.3) | 176 (50.7) | 303 (90.2) | 97 (28.9) | |||

| Salt-related behaviors | 0.015 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Low | 510 (87.2) | 267 (53.2) | 466 (94.7) | 168 (34.4) | |||

| High | 75 (12.8) | 28 (37.3) | 41 (56.2) | 6 (8.1) | |||

| Self-perceived food environmental settings | |||||||

| Food Availability | 0.049 | 0.040 | 0.688 | ||||

| Low | 321 (54.9) | 150 (46.7) | 269 (87.3) | 98 (31.6) | |||

| High | 264 (45.1) | 145 (54.6) | 238 (92.6) | 76 (43.7) | |||

| Food Accessibility | 0.496 | 0.496 | 0.389 | ||||

| Low | 412 (70.4) | 204 (49.5) | 354 (89.2) | 127 (32.0) | |||

| High | 173 (29.6) | 91 (52.6) | 153 (91.1) | 47 (28.3) | |||

| Food Purchasability | 0.730 | 0.550 | 0.511 | ||||

| Low | 377 (57.6) | 172 (51.0) | 294 (89.1) | 104 (32.0) | |||

| High | 248 (42.4) | 123 (49.6) | 213 (90.6) | 70 (29.4) |

| Variables | Total 585 (100.0) | High Sodium Intake | 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main ways of dietary behavior | 2.125 | 0.547 | ||

| Students’ canteen | 456 (76.8) | 221 (48.5) | ||

| Takeaway food | 71 (12.0) | 41 (57.7) | ||

| Restaurant | 57 (9.6) | 28 (49.1) | ||

| Home | 10 (1.7) | 5 (50.0) | ||

| Outside eating # | 6.586 | 0.010 | ||

| <1 time per week | 58 (10.3) | 20 (34.5) | ||

| ≥1 time per week | 507 (89.7) | 151 (52.3) | ||

| Takeaway ordering # | 13.202 | <0.001 | ||

| <1 time per week | 389 (69.1) | 177 (45.5) | ||

| ≥1 time per week | 117 (30.9) | 108 (62.1) | ||

| Re-adding salt to cooked meals | 1.226 | 0.268 | ||

| Yes | 49 (8.4) | 21 (42.9) | ||

| No | 536 (91.6) | 526(91.6) | ||

| Like spicy snacks | 0.050 | 0.823 | ||

| Yes | 316 (54.0) | 158 (50.0) | ||

| No | 269 (46.0) | 137 (50.9) |

| Variables | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male = Ref) | 1.438 (1.017, 2033) * | 1.457 (1.029, 2.064) * |

| Outside eating (<1 time per week = Ref) | 2.179 (1.097, 3.588) *** | 1.983 (1.097, 3.588) * |

| Takeaway ordering (<1 time per week = Ref) | 2.031 (1.397, 2.952) *** | 2.027 (1.390, 2.957) *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, M.; Xi, Y.; Huo, J.; Xiang, C.; Yong, C.; Liang, J.; Zou, H.; Pan, Y.; Xie, Q.; Lin, Q. Association between Eating Habits and Sodium Intake among Chinese University Students. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071570

Wu M, Xi Y, Huo J, Xiang C, Yong C, Liang J, Zou H, Pan Y, Xie Q, Lin Q. Association between Eating Habits and Sodium Intake among Chinese University Students. Nutrients. 2023; 15(7):1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071570

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Minchan, Yue Xi, Jiaqi Huo, Caihong Xiang, Cuiting Yong, Jiajing Liang, Hanshuang Zou, Yunfeng Pan, Qingqing Xie, and Qian Lin. 2023. "Association between Eating Habits and Sodium Intake among Chinese University Students" Nutrients 15, no. 7: 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071570