Effects of Oral Collagen for Skin Anti-Aging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

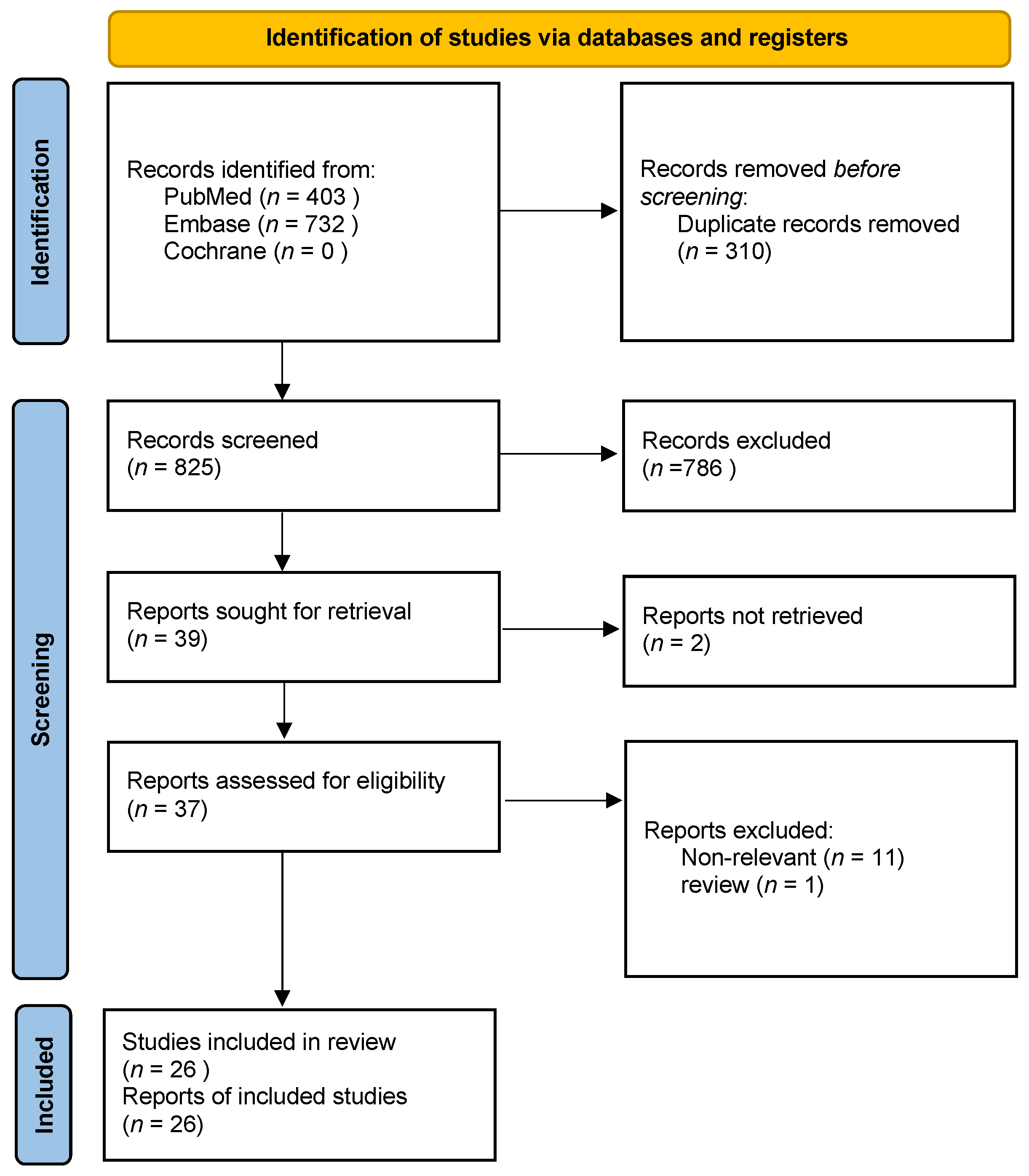

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy, Inclusion Criteria, and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis, Sensitivity Analysis and Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Research Results and Study Characteristics

3.2. Study Characteristics

| Author (Year) | Female/Male | Age Range | Time (Weeks) | Intervention (Origin) | Outcome Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proksch et al. (2014a) [18] | 60/0 | 35–55 | 8, 12 | 2.5 g HC/5 g HC (porcine) | Elasticity/hydration/trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL)/wrinkles |

| Proksch et al. (2014b) [38] | 107/0 | 45–65 | 8, 12 | 2.5 g collagen peptides | Wrinkles/biopsy/procollagen type/elastin/fibrillin |

| Yoon et al. (2014) [39] | 44/0 | >44 | 12 | 3 g HC (fish) | Procollagen type 1/fibrillin 1/metalloproteinases 1 and 12/biopsies/immunohistochemical staining |

| Di Cerbo et al. (2014) [40] | 30/0 | 40–45 | 4.5 | 372 mg HC | Cutaneous pH/hydration/sebum/elasticity/skin tone/elastin/elastase 2/fibronectin/hyaluronic acid/carbonyl proteins |

| Choi et al. (2014) [32] | 24/8 | 30–48 | 5 | 3 g collagen peptides | Skin hydration/elasticity/TEWL/erythema/satisfaction questionnaire |

| Sugihara, Inoue, and Wang (2015) [28] | 53/0 | 35–55 | 8 | 2.5 g HC (fish) | Hydration/elasticity/wrinkles |

| Campos et al. (2015) [29] | 60/0 | 40–50 | 12 | 10 g HC | Corneal stratum hydration/skin viscoelasticity/dermal echogenicity/high-resolution photography |

| Asserin et al. (2015) [30] | 134/0 | 40–65 | 8, 12 | 10 g HC (porcine)/10 g HC (fish) | Skin moisture/TEWL/dermal density/dermal echogenicity/dermal collagen fragmentation |

| Inoue, Sugihara, and Wang (2016) [34] | 80/0 | 35–55 | 8 | 2.5 g collagen peptides | Skin moisture/elasticity/wrinkles |

| Genovese, Corbo, and Sibilla (2017) [41] | 111/9 | 40–60 | 12 | 5 g HC | Elasticity/biopsies/subjective questionnaire |

| Koizumi et al. (2017) [27] | 71/0 | 30–60 | 12 | 3 g collagen peptides | Wrinkles/moisture/elasticity/blood tests (γ-glutamyltransferase, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume, red blood cell, platelet, white blood cell, bilirubin, creatinine, total cholesterol, glucose, hemoglobin, hematocrit, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total protein and albumin) |

| Czajka et al. (2018) [42] | 120/0 | 21–70 | 12 | 4 g HC | Elasticity/biopsies/self-perception questionnaire |

| Kim (2018) [43] | 70/0 | 40–60 | 12 | 1000 mg collagen (fish) | Skin hydration/wrinkling/elasticity |

| Ito, Seki, and Ueda (2018) [31] | 17/4 | 30–50 | 8 | 10 g collagen peptides (fish) | Elasticity/moisture/TEWL/skin pH/spots/wrinkle/skin pores/texture/density/collagen score/growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) |

| Bolke et al. (2019) [26] | 72/0 | >35 | 12, 16 | 2.5 g collagen peptides | Hydration/elasticity/wrinkles/skin density/subjective questionnaire |

| Schwartz et al. (2019) [35] | 113/0 | 36–59 | 12 | 0.6 g HC (chicken) | Erythema/hydration/TEWL/elasticity/wrinkles/dermal collagen/subjective questionnaire |

| Zmitek et al. (2020) [44] | 31/0 | 40–65 | 12 | 4 g HC (fish) | Dermal density and thickness/viscoelasticity/hydration/TEWL/wrinkles/moisture/dermal microrelief |

| Laing et al. (2020) [45] | 60/0 | 40–70 | 12 | 2.5 g collagen peptides | Dermal collagen fragmentation/subjective questionnaire |

| Sangsuwan and Asawanonda (2020) [37] | 36/0 | 50–60 | 4, 8 | 5 g HC | Elasticity |

| Nomoto and Iizaka (2020) [33] | 27/12 | >65 | 8 | 12 g collagen peptides | Stratum corneum hydration/elasticity |

| Ping (2020) [46] | 50/0 | 35–50 | 8 | 5.5 g collagen (fish) | Skin hydration/brightness/texture/crow’s feet/collagen content |

| Evans (2020) [47] | 50/0 | 45–60 | 12 | 10 g HC (fish) | Wrinkles/elasticity/self-reported appearance |

| Tak (2021) [48] | 84/0 | 40–60 | 12 | 1000 mg collagen tripeptides | Hydration/elasticity/wrinkles |

| Miyanaga (2021) [49] | 99/0 | 35–50 | 12 | 1 g HC/5 g HC | Skin water content/TEWL/elasticity/thickness |

| Jung (2021) [50] | 25/25 | 35–60 | 12 | 1000 mg collagen (fish) | Skin hydration/TEWL/texture/flexibility |

| Bianchi (2022) [51] | 52/0 | 40–60 | 8 | 5 g HC | Skin moisturization/elasticity/wrinkle depth |

3.3. Meta-Analysis Results

3.3.1. Pooled Analysis of Selected Studies

3.3.2. Subgroup Analysis

3.4. Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Hydration

4.2. Elasticity

4.3. Mechanism

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zouboulis, C.C. Human Skin: An Independent Peripheral Endocrine Organ. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2000, 54, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.E.; Huh, C.S.; Ra, J.; Choi, I.D.; Jeong, J.W.; Kim, S.H.; Ryu, J.H.; Seo, Y.K.; Koh, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Ahn, Clinical Evidence of Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum HY7714 on Skin Aging: A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honigman, R.; Castle, D.J. Aging and cosmetic enhancement. Clin. Interv. Aging 2006, 1, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lordan, R. Dietary supplements and nutraceuticals market growth during the coronavirus pandemic—Implications for consumers and regulatory oversight. PharmaNutrition 2021, 18, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uitto, J. Connective tissue biochemistry of the aging dermis. Age-related alterations in collagen and elastin. Dermatol. Clin. 1986, 4, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoulders, M.D.; Raines, R.T. Collagen structure and stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 929–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, C.; Stewart, K.M.; Weaver, V.M. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 4195–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja-Agius, J.; Muscat-Baron, Y.; Brincat, M.P. Skin ageing. Menopause Int. 2007, 13, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognia, J.L.; Braverman, I.M.; Rousseau, M.E.; Sarrel, P.M. Skin changes in menopause. Maturitas 1989, 11, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Branco, C.; Duran, M.; González-Merlo, J. Skin collagen changes related to age and hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas 1992, 15, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, S.P. Biochemistry and functional significance of collagen cross-linking. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schagen, S.K.; Zampeli, V.A.; Makrantonaki, E.; Zouboulis, C.C. Discovering the link between nutrition and skin aging. Dermatoendocrinology 2012, 4, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.I.; Lee, S.G.; Jung, I.; Suk, J.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, D.U.; Lee, J.H. Effect of a Topical Collagen Tripeptide on Antiaging and Inhibition of Glycation of the Skin: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockerham, K.; Hsu, V.J. Collagen-based dermal fillers: Past, present, future. Facial Plast. Surg. 2009, 25, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-López, A.; Morales-Peñaloza, A.; Martínez-Juárez, V.M.; Vargas-Torres, A.; Zeugolis, D.I.; Aguirre-Álvarez, G. Hydrolyzed Collagen-Sources and Applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miranda, R.B.; Weimer, P.; Rossi, R.C. Effects of hydrolyzed collagen supplementation on skin aging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Ito, K.; Iwai, K.; Sato, K. Comparison of quantity and structures of hydroxyproline-containing peptides in human blood after oral ingestion of gelatin hydrolysates from different sources. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, E.; Segger, D.; Degwert, J.; Schunck, M.; Zague, V.; Oesser, S. Oral supplementation of specific collagen peptides has beneficial effects on human skin physiology: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2014, 27, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesser, S.; Adam, M.; Babel, W.; Seifert, J. Oral administration of 14C labeled gelatin hydrolysate leads to an accumulation of radioactivity in cartilage of mice (C57/BL). J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 1891–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers 2021, 13, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer, version 4.6; Ankit Rohatgi: Pacifica, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolke, L.; Schlippe, G.; Gerss, J.; Voss, W. A Collagen Supplement Improves Skin Hydration, Elasticity, Roughness, and Density: Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Blind Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koizumi, S.; Inoue, N.; Shimizu, M.; Kwon, C.-J.; Kim, H.-Y.; Park, K.S. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with Fish Scales-Derived Collagen Peptides on Skin Parameters and Condition: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2017, 24, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, F.; Inoue, N.; Wang, X. Clinical effects of ingesting collagen hydrolysate on facial skin properties. JPN Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 43, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, P.M.; Melo, M.O.; Calixto, L.S.; Fossa, M.M. An Oral Supplementation Based on Hydrolyzed Collagen and Vitamins Improves Skin Elasticity and Dermis Echogenicity: A Clinical Placebo-Controlled Study. Clin. Pharmacol. Biopharm. 2015, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asserin, J.; Lati, E.; Shioya, T.; Prawitt, J. The effect of oral collagen peptide supplementation on skin moisture and the dermal collagen network: Evidence from an ex vivo model and randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2015, 14, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Seki, S.; Ueda, F. Effects of Composite Supplement Containing Collagen Peptide and Ornithine on Skin Conditions and Plasma IGF-1 Levels-A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Ko, E.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, B.G.; Shin, H.J.; Seo, D.B.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, M.N. Effects of collagen tripeptide supplement on skin properties: A prospective, randomized, controlled study. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2014, 16, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomoto, T.; Iizaka, S. Effect of an Oral Nutrition Supplement Containing Collagen Peptides on Stratum Corneum Hydration and Skin Elasticity in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Multicenter Open-label Randomized Controlled Study. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2020, 33, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, N.; Sugihara, F.; Wang, X. Ingestion of bioactive collagen hydrolysates enhance facial skin moisture and elasticity and reduce facial ageing signs in a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical study. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4077–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.R.; Hammon, K.A.; Gafner, A.; Dahl, A.; Guttman, N.; Fong, M.; Schauss, A.G. Novel Hydrolyzed Chicken Sternal Cartilage Extract Improves Facial Epidermis and Connective Tissue in Healthy Adult Females: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2019, 25, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.R.; Park, J. Ingestion of BioCell Collagen®, a novel hydrolyzed chicken sternal cartilage extract; enhanced blood microcirculation and reduced facial aging signs. Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 7, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sangsuwan, W.; Asawanonda, P. Four-weeks daily intake of oral collagen hydrolysate results in improved skin elasticity, especially in sun-exposed areas: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 32, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proksch, E.; Schunck, M.; Zague, V.; Segger, D.; Degwert, J.; Oesser, S. Oral intake of specific bioactive collagen peptides reduces skin wrinkles and increases dermal matrix synthesis. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2014, 27, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.S.; Cho, H.H.; Cho, S.; Lee, S.R.; Shin, M.H.; Chung, J.H. Supplementating with dietary astaxanthin combined with collagen hydrolysate improves facial elasticity and decreases matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -12 expression: A comparative study with placebo. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cerbo, A.; Laurino, C.; Palmieri, B.; Iannitti, T. A dietary supplement improves facial photoaging and skin sebum, hydration and tonicity modulating serum fibronectin, neutrophil elastase 2, hyaluronic acid and carbonylated proteins. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 144, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, L.; Corbo, A.; Sibilla, S. An Insight into the Changes in Skin Texture and Properties following Dietary Intervention with a Nutricosmeceutical Containing a Blend of Collagen Bioactive Peptides and Antioxidants. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2017, 30, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajka, A.; Kania, E.M.; Genovese, L.; Corbo, A.; Merone, G.; Luci, C.; Sibilla, S. Daily oral supplementation with collagen peptides combined with vitamins and other bioactive compounds improves skin elasticity and has a beneficial effect on joint and general wellbeing. Nutr. Res. 2018, 57, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-U.; Chung, H.-C.; Choi, J.; Sakai, Y.; Lee, B.-Y. Oral Intake of Low-Molecular-Weight Collagen Peptide Improves Hydration, Elasticity and Wrinkling in Human Skin: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmitek, K.; Zmitek, J.; Butina, M.R.; Pogacnik, T. Effects of a Combination of Water-Soluble CoenzymeQ10 and Collagen on Skin Parameters and Condition:Results of a Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laing, S.; Bielfeldt, S.; Ehrenberg, C.; Wilhelm, K.P. A Dermonutrient Containing Special Collagen Peptides Improves Skin Structure and Function: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Triple-Blind Trial Using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy on the Cosmetic Effects and Tolerance of a Drinkable Collagen Supplement. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.; Alexander, R.A.; Liang, C.H.; Liu, C.; Lin, Y.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Chan, L.P.; Kuan, C.M. Collagen formula with Djulis for improvement of skin hydration, brightness, texture, crow’s feet, and collagen content: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.; Lewis, E.D.; Zakaria, N.; Pelipyagina, T.; Guthrie, N. A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study to evaluate the efficacy of a freshwater marine collagen on skin wrinkles and elasticity. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, Y.J.; Shin, D.K.; Kim, A.H.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, Y.L.; Ko, H.C.; Kim, Y.W.; Lee, S.Y. Effect of Collagen Tripeptide and Adjusting for Climate Change on Skin Hydration in Middle-Aged Women: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 608903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanaga, M.; Uchiyama, T.; Motoyama, A.; Ochiai, N.; Ueda, O.; Ogo, M. Oral Supplementation of Collagen Peptides Improves Skin Hydration by Increasing the Natural Moisturizing Factor Content in the Stratum Corneum: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2021, 34, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Kim, S.H.; Joo, K.M.; Lim, S.H.; Shin, J.H.; Roh, J.; Kim, E.; Park, C.W.; Kim, W. Oral Intake of Enzymatically Decomposed AP Collagen Peptides Improves Skin Moisture and Ceramide and Natural Moisturizing Factor Contents in the Stratum Corneum. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.M.; Angelinetta, C.; Rizzi, G.; Praticò, A.; Villa, R. Evaluation of the Efficacy of a Hydrolyzed Collagen Supplement for Improving Skin Moisturization, Smoothness, and Wrinkles. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2022, 15, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, L. Skin ageing and its treatment. J. Pathol. 2007, 211, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.J.; Stern, R. Age-dependent changes of hyaluronan in human skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1994, 102, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohara, H.; Iida, H.; Ito, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Nomura, Y. Effects of Pro-Hyp, a collagen hydrolysate-derived peptide, on hyaluronic acid synthesis using in vitro cultured synovium cells and oral ingestion of collagen hydrolysates in a guinea pig model of osteoarthritis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 2096–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Xiao, Z.; Tong, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ge, C. Oral Intake of Chicken Bone Collagen Peptides Anti-Skin Aging in Mice by Regulating Collagen Degradation and Synthesis, Inhibiting Inflammation and Activating Lysosomes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Wu, J.; Qian, G.; Cheng, H. Effectiveness of Dietary Supplement for Skin Moisturizing in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 895192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, A.A.; Bhat, R. Fish gelatin: Properties, challenges, and prospects as an alternative to mammalian gelatins. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T.; Suzuki, N. Isolation of collagen from fish waste material—Skin, bone and fins. Food Chem. 2000, 68, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exposito, J.Y.; Valcourt, U.; Cluzel, C.; Lethias, C. The fibrillar collagen family. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelse, K.; Poschl, E.; Aigner, T. Collagens—Structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2003, 55, 1531–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, T.; Aumailley, M. The extracellular matrix of the dermis: Flexible structures with dynamic functions. Exp. Dermatol. 2011, 20, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, B. Effects of collagen peptides intake on skin ageing and platelet release in chronologically aged mice revealed by cytokine array analysis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C.; Mikhal, E.V.; Suprun, M.V.; Papacharalambous, M.; Truhanov, A.I.; Korkina, L.G. Skin Antiageing and Systemic Redox Effects of Supplementation with Marine Collagen Peptides and Plant-Derived Antioxidants: A Single-Blind Case-Control Clinical Study. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 4389410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, P.M.; Melo, M.O.; César, F.C.S. Topical application and oral supplementation of peptides in the improvement of skin viscoelasticity and density. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.I.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, E.; Jung, I.; Suk, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.H. Anti-aging effect of an oral disintegrating collagen film: A prospective, single-arm study. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, B. Effect of Orally Administered Collagen Peptides from Bovine Bone on Skin Aging in Chronologically Aged Mice. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addor, F.A.S.; Vieira, J.C.; Melo, C.S.A. Improvement of dermal parameters in aged skin after oral use of a nutrient supplement. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 11, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Luo, Z.; Tang, J.; Lin, L.; Du, Z.; Dong, C. The effects and mechanism of collagen peptide and elastin peptide on skin aging induced by D-galactose combined with ultraviolet radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2020, 210, 111964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, R.; Crombach, N.; Gijsen, A.P.; Walrand, S.; Fauquant, J.; Kies, A.K.; Lemosquet, S.; Saris, W.H.; Boirie, Y.; van Loon, L.J. Ingestion of a protein hydrolysate is accompanied by an accelerated in vivo digestion and absorption rate when compared with its intact protein. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazaki, M.; Ito, Y.; Yamada, M.; Goulas, S.; Teramoto, S.; Nakaya, M.-A.; Ohno, S.; Yamaguchi, K. Oral Ingestion of Collagen Hydrolysate Leads to the Transportation of Highly Concentrated Gly-Pro-Hyp and Its Hydrolyzed Form of Pro-Hyp into the Bloodstream and Skin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 2315–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe-Kamiyama, M.; Shimizu, M.; Kamiyama, S.; Taguchi, Y.; Sone, H.; Morimatsu, F.; Shirakawa, H.; Furukawa, Y.; Komai, M. Absorption and effectiveness of orally administered low molecular weight collagen hydrolysate in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Ohara, H.; Itoh, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Takahashi, S. Clinical effects of fish type I collagen hydrolysate on skin properties. ITE Lett. 2006, 7, 386–390. [Google Scholar]

- Gref, R.; Deloménie, C.; Maksimenko, A.; Gouadon, E.; Percoco, G.; Lati, E.; Desmaële, D.; Zouhiri, F.; Couvreur, P. Vitamin C-squalene bioconjugate promotes epidermal thickening and collagen production in human skin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polcz, M.E.; Barbul, A. The Role of Vitamin A in Wound Healing. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2019, 34, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinder, R.; Cooley, R.; Vlad, L.G.; Molnar, J.A. Vitamin A and Wound Healing. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2019, 34, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, M.J.; Jones, J.D.; Woessner, A.E.; Quinn, K.P. Skin Structure-Function Relationships and the Wound Healing Response to Intrinsic Aging. Adv. Wound Care 2020, 9, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pu, S.-Y.; Huang, Y.-L.; Pu, C.-M.; Kang, Y.-N.; Hoang, K.D.; Chen, K.-H.; Chen, C. Effects of Oral Collagen for Skin Anti-Aging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2080. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092080

Pu S-Y, Huang Y-L, Pu C-M, Kang Y-N, Hoang KD, Chen K-H, Chen C. Effects of Oral Collagen for Skin Anti-Aging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2023; 15(9):2080. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092080

Chicago/Turabian StylePu, Szu-Yu, Ya-Li Huang, Chi-Ming Pu, Yi-No Kang, Khanh Dinh Hoang, Kee-Hsin Chen, and Chiehfeng Chen. 2023. "Effects of Oral Collagen for Skin Anti-Aging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 15, no. 9: 2080. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092080

APA StylePu, S.-Y., Huang, Y.-L., Pu, C.-M., Kang, Y.-N., Hoang, K. D., Chen, K.-H., & Chen, C. (2023). Effects of Oral Collagen for Skin Anti-Aging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 15(9), 2080. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092080