Effect of Methylfolate, Pyridoxal-5′-Phosphate, and Methylcobalamin (SolowaysTM) Supplementation on Homocysteine and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Patients with Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase, Methionine Synthase, and Methionine Synthase Reductase Polymorphisms: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

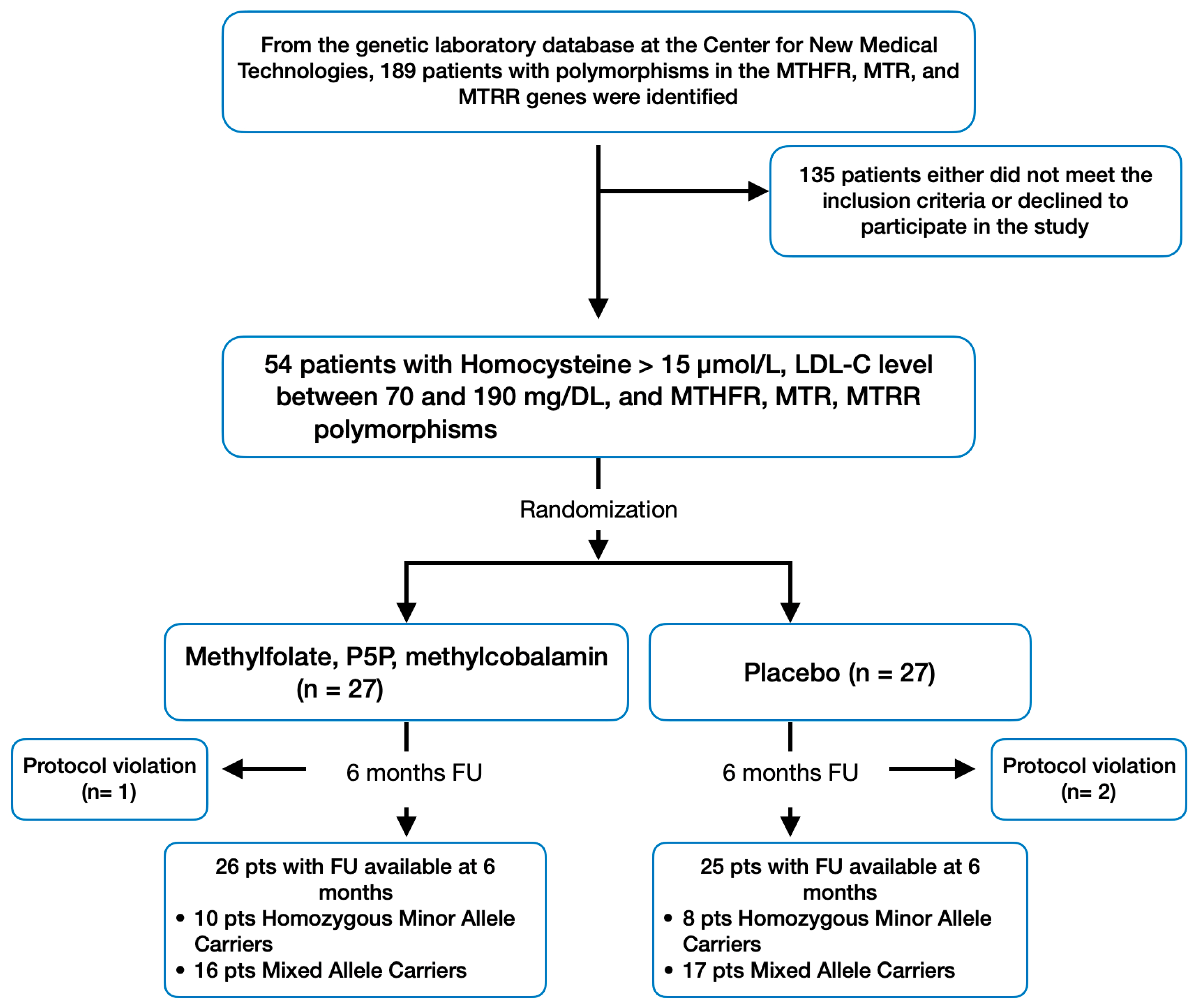

2.1. Patient Population and Design

- Age between 40 and 75;

- Homocysteine levels greater than 15 µmol/L and LDL-C level between 70 and 190 mg/dL, confirmed in at least two sequential checks conducted within the last six months prior to signing the consent form;

- Presence of at least one minor allele in any of the following genetic polymorphisms: rs1801133 (MTHFR C677T), rs1801131 (MTHFR A1298C), rs1805087 (MTR A2756G), and rs1801394 (MTRR A66G) [4].

- Personal history of cardiovascular disease or high risk (≥20%);

- Triglycerides (TG) ≥ 400 mg/dL;

- Obesity (Body Mass Index > 30 kg/m2);

- Assumption of lipid-lowering drugs or supplements affecting lipid metabolism within the last three months;

- Use of medications or supplements known to affect homocysteine levels, such as B-vitamins and certain antihypertensives, within the last three months;

- Diabetes mellitus;

- Known severe or uncontrolled thyroid, liver, renal, or muscle diseases.

2.2. Study Endpoints and Assessments

2.3. Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Power

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

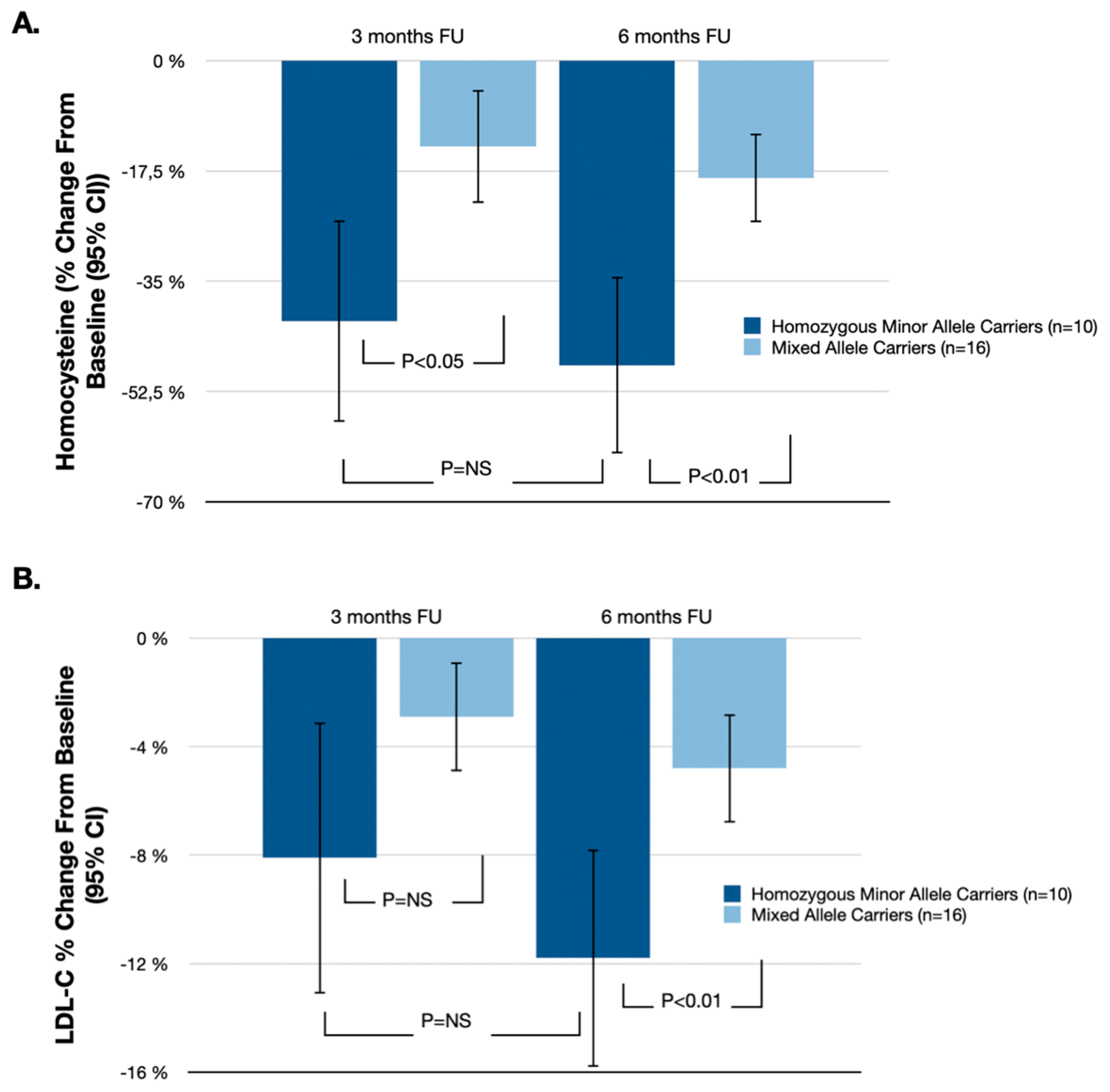

3.1. Primary Endpoint

3.2. Other Secondary End Points

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Lippi, G. Worldwide burden of LDL cholesterol: Implications in cardiovascular disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S. The current status of homocysteine as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A mini review. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2018, 16, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strain, J.J.; Dowey, L.; Ward, M.; Pentieva, K.; McNulty, H. B-vitamins, homocysteine metabolism and CVD. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.-X.; Dai, S.-X.; Zheng, J.-J.; Liu, J.-Q.; Huang, J.-F. Homocysteine Metabolism Gene Polymorphisms and the Risk of Folate Deficiency. Nutrients 2015, 7, 6670–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Zhao, R.; Shen, M.; Ye, J.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Hua, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Role of genetic mutations in folate-related enzyme genes on Male Infertility. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidl, D.; Howorka, K.; Szegedi, S.; Stjepanek, K.; Puchner, S.; Bata, A.; Scheschy, U.; Aschinger, G.; Werkmeister, R.M.; Schmetterer, L.; et al. Vitamin supplementation and retinal blood flow in diabetes. Mol. Vis. 2020, 26, 326–333. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, J.F.; DeRatt, B.N.; Rios-Avila, L.; Ralat, M.; Stacpoole, P.W. Vitamin B6 and hydrogen sulfide production in the transsulfuration pathway. Biochimie 2016, 126, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froese, D.S.; Fowler, B.; Baumgartner, M.R. Vitamin B12, folate, and the methionine remethylation cycle—Biochemistry, pathways, and regulation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokushalov, E.; Ponomarenko, A.; Garcia, C.; Pak, I.; Shrainer, E.; Seryakova, M.; Johnson, M.; Miller, R. The Impact of Glu-comannan, Inulin, and Psyllium Supplementation (SolowaysTM) on Weight Loss in Adults with FTO, LEP, LEPR, and MC4R Polymorphisms: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokushalov, E.; Ponomarenko, A.; Bayramova, S.; Garcia, C.; Pak, I.; Shrainer, E.; Voronina, E.; Sokolova, E.; Johnson, M.; Miller, R. Evaluating the Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acid (SolowaysTM) Supplementation on Lipid Profiles in Adults with PPARG Polymorphisms: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, D.; Law, M.; Morris, J. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: Causality evidence from a meta-analysis. BMJ 2002, 325, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen, R.I.M.A. Genetic modulation of homocysteinemia. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2000, 26, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosst, P.; Blom, H.J.; Milos, R.; Goyette, P.; Sheppard, C.A.; Matthews, R.G.; Boers, G.J.; den Heijer, M.; Kluijtmans, L.A.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; et al. A genetic risk factor for vascular disease. Nat. Genet. 1995, 10, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P.F.; Bostom, A.G.; Selhub, J.; Rich, S.; Ellison, R.C.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; A Gravel, R.; Rozen, R. Effects of polymorphisms of methionine synthase and methionine synthase reductase on total plasma homocysteine in the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Atherosclerosis 2003, 166, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, D.; Kluijtmans, L.; Barbaux, S.; Mcmaster, D.; Young, I.; Yarnell, J.; Evans, A.; Whitehead, A. The methionine syn-thase reductase (MTRR) A66G polymorphism is a novel genetic determinant of plasma homocysteine concentrations. Atherosclerosis 2001, 157, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, G.-C.; Dai, X.-L.; Wang, J.; Jin, M.-H.; Mi, N.-N.; Wang, S.-Q. The N-terminus of MTRR plays a role in MTR reactivation cycle beyond electron transfer. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 100, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques, P.F.; Selhub, J.; Bostom, A.G.; Wilson, P.W.; Rosenberg, I.H. Impact of folic acid fortification on plasma folate and total homocysteine concentrations. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiuve, S.E.; Sampson, L.; Willett, W.C. The Association Between a Nutritional quality index and risk of chronic disease. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selhub, J.; Bagley, L.C.; Miller, J.; Rosenberg, I.H. B vitamins, homocysteine, and neurocognitive function in the elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 614S–620S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNulty, H.; Dowey, L.R.C.; Strain, J.J.; Dunne, A.; Ward, M.; Molloy, A.M.; McAnena, L.B.; Hughes, J.P.; Hannon-Fletcher, M.; Scott, J.M. Riboflavin and homocysteine in MTHFR 677C->T polymorphism. Circulation 2006, 113, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saposnik, G.; Ray, J.G.; Sheridan, P.; McQueen, M.; Lonn, E. Homocysteine-lowering therapy and stroke risk, severity, and disability: Additional findings from the HOPE 2 trial. Stroke 2009, 40, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonn, E.; Yusuf, S.; Arnold, M.J.; Sheridan, P.; Pogue, J.; Micks, M.; McQueen, M.; Probstfield, J.; Fodor, G.; Held, C.; et al. Homocysteine lowering with folic acid and B vitamins in vascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, T.A.; Ito, M.K.; Maki, K.C.; Orringer, C.E.; Bays, H.E.; Jones, P.; McKenney, J.; Grundy, S.; Gill, E.; Wild, R.; et al. National lipid association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2015, 9, 129–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Methylfolate, P5P, Methylcobalamin (n = 26) | Placebo (n = 25) | p-Value | Homozygous Minor Allele Carriers (n = 18) | Mixed Allele Carriers (n = 33) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 59.2 ± 6.2 | 57.5 ± 9.1 | p = 0.45 | 57.3 ± 7.8 | 59.1 ± 8.9 | p = 0.07 |

| Women, % | 57.7 | 52.0 | p = 0.61 | 60 | 52 | p = 0.21 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.5 ± 3.1 | 28.9 ± 3.3 | p = 0.33 | 29.2 ± 3.2 | 27.5 ± 3.6 | p = 0.09 |

| 10-y ASCVD risk, % | 9.9 | 8.5 | p = 0.75 | 10 | 8.5 | p = 0.11 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 18.5 ± 4.1 | 19.1 ± 3.8 | p = 0.81 | 25.1 ± 4.1 | 17.3 ± 3.9 | p < 0.01 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 180 ± 21 | 185 ± 31 | p = 0.68 | 190 ± 29 | 180 ± 25 | p = 0.08 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 125.4 ± 27.2 | 131.7 ± 29.1 | p = 0.57 | 150.1 ± 29.3 | 127.7 ± 26.8 | p < 0.01 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 52.4 ± 6.5 | 48.9 ± 4.1 | p = 0.11 | 47.6 ± 4.8 | 52.2 ± 5.8 | p = 0.05 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 159 ± 32 | 148 ± 27 | p = 0.42 | 165 ± 29 | 147 ± 25 | p = 0.18 |

| hsCRP, mg/L | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | p = 0.09 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | p = 0.23 |

| Methylfolate, P5P, Methylcobalamin (n = 26) % Change from Baseline (95% CI) | Placebo (n = 25) % Change from Baseline (95% CI) | % Difference (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homocysteine | −30.0% (−39.7%, −20.3%) | 1.8% (−4.8%, 6.8%) | −31.8% (−46.5%, −15.5%) | p < 0.01 |

| LDL-C | −7.5% (−10.3%, −4.7%) | 2.6% (−1.6%, 5.6%) | −10.1% (−15.9%, −3.1%) | p < 0.01 |

| Total cholesterol | −2.5% (−4.8%, −0.3%) | 2.1% (−0.6%, 4.8%) | −4.6% (−9.6%, 0.3%) | p = 0.08 |

| HDL-C | 1.6% (−1.4%, 4.6%) | −0.5% (−3.0%, 2.0%) | 2.1% (−3.4%, 7.6%) | p = 0.16 |

| Triglycerides | −3.7% (−7.7%, 0.3%) | 2.8% (−0.3%, 5.9%) | −6.5% (−13.6%, 0.6%) | p = 0.11 |

| hsCRP | −5.3% (−13.0%, 2.5%) | −3.2% (−8.3%, 1.9%) | −2.1% (−14.9%, 10.8%) | p = 0.23 |

| Homozygous Minor Allele Carriers (n = 10) % Change from Baseline (95% CI) | Mixed Allele Carriers (n = 16) % Change from Baseline (95% CI) | % Difference (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homocysteine | −48.3% (−62.3%, −34.3%) | −18.6% (−25.6%, −11.6%) | −29.7% (−50.7%, −8.7%) | p < 0.01 |

| LDL-C | −11.8% (−15.8%, −7.8%) | −4.8% (−6.8%, −2.8%) | −7.0% (−13.0%, −1.0%) | p < 0.01 |

| Total cholesterol | −3.2% (−5.6%, −0.8%) | −2.1% (−4.3%, 0.1%) | −1.1% (−5.7%, 3.5%) | p = 0.07 |

| HDL-C | 2.8% (−0.5%, 6.1%) | 0.9% (−1.9%, 3.7%) | 1.9% (−4.2%, 8.0%) | p = 0.12 |

| Triglycerides | −5.1% (−10.9%, 0.7%) | −2.8% (−5.7%, 0.1%) | −2.3% (−11.0%, 6.4%) | p = 0.09 |

| hsCRP | −3.9% (−11.6%, 3.8%) | −6.1% (−13.9%, 1.7%) | 2.2% (−17.7%, 13.3%) | p = 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pokushalov, E.; Ponomarenko, A.; Bayramova, S.; Garcia, C.; Pak, I.; Shrainer, E.; Ermolaeva, M.; Kudlay, D.; Johnson, M.; Miller, R. Effect of Methylfolate, Pyridoxal-5′-Phosphate, and Methylcobalamin (SolowaysTM) Supplementation on Homocysteine and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Patients with Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase, Methionine Synthase, and Methionine Synthase Reductase Polymorphisms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111550

Pokushalov E, Ponomarenko A, Bayramova S, Garcia C, Pak I, Shrainer E, Ermolaeva M, Kudlay D, Johnson M, Miller R. Effect of Methylfolate, Pyridoxal-5′-Phosphate, and Methylcobalamin (SolowaysTM) Supplementation on Homocysteine and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Patients with Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase, Methionine Synthase, and Methionine Synthase Reductase Polymorphisms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111550

Chicago/Turabian StylePokushalov, Evgeny, Andrey Ponomarenko, Sevda Bayramova, Claire Garcia, Inessa Pak, Evgenya Shrainer, Marina Ermolaeva, Dmitry Kudlay, Michael Johnson, and Richard Miller. 2024. "Effect of Methylfolate, Pyridoxal-5′-Phosphate, and Methylcobalamin (SolowaysTM) Supplementation on Homocysteine and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Patients with Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase, Methionine Synthase, and Methionine Synthase Reductase Polymorphisms: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111550

APA StylePokushalov, E., Ponomarenko, A., Bayramova, S., Garcia, C., Pak, I., Shrainer, E., Ermolaeva, M., Kudlay, D., Johnson, M., & Miller, R. (2024). Effect of Methylfolate, Pyridoxal-5′-Phosphate, and Methylcobalamin (SolowaysTM) Supplementation on Homocysteine and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Patients with Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase, Methionine Synthase, and Methionine Synthase Reductase Polymorphisms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 16(11), 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111550