Abstract

There is a rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Papua New Guinea (PNG), adding to the disease burden from communicable infectious diseases and thus increasing the burden on the healthcare system in a low-resource setting. The aim of this review was to identify health and nutrition promotion programs conducted in PNG and the enablers and barriers to these programs. Four electronic databases and grey literature were searched. Two reviewers completed screening and data extraction. This review included 23 papers evaluating 22 health and nutrition promotion programs, which focused on the Ottawa Charter action areas of developing personal skills (12 programs), reorienting health services (12 programs) and strengthening community action (6 programs). Nineteen programs targeted communicable diseases; two addressed NCDs, and one addressed health services. Enablers of health promotion programs in PNG included community involvement, cultural appropriateness, strong leadership, and the use of mobile health technologies for the decentralisation of health services. Barriers included limited resources and funding and a lack of central leadership to drive ongoing implementation. There is an urgent need for health and nutrition promotion programs targeting NCDs and their modifiable risk factors, as well as longitudinal study designs for the evaluation of long-term impact and program sustainability.

1. Introduction

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a linguistically, ethnically, culturally and geographically diverse Pacific Island Nation, having over 800 living languages, including three national spoken languages of English, Tok Pisin and Hiri Motu, and consisting of four distinct geographical regions, namely the Highland region, Southern region (including Port Moresby, the Capital of PNG), Momase region, and New Guinea Islands region. The diversity and isolation of geographic regions and a large number of cultural groups historically have made it hard to govern since its independence from Australia in 1975 [1], but also made it challenging to develop health promotion initiatives, communication and policies for health for the whole country [1].

The population of PNG face the dual burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), with the country undergoing an epidemiological shift from infectious diseases to NCDs [2]. While mortality from infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), malaria, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) still make up 35% of total deaths, at the same time, mortality from NCDs, such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has increased dramatically [2]. In 2018–20, NCD-related deaths in PNG accounted for 47% of total deaths, showing a 10% increase over the past 50 years [2]. This places significant pressure on the already compromised healthcare system with added socioeconomic burden and negative effects on individual and community health [3].

As with other Low to Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) across the Pacific, PNG is undergoing rapid economic growth, social transition and urbanisation due to increasing resource development [4]. This has coincided with the nutrition transition phenomenon whereby the population’s traditional diet and physical activity behaviours have shifted to more processed, high-energy dense foods, increased dependence on global food supply and sedentary activity [4]. Similar to other Pacific LMICs, where the economic and nutrition transition have been associated with increased NCD prevalence [5,6], in PNG, the nutrition transition is more apparent in regions with higher exposure to urbanisation and modernisation and therefore, the peri-urban and urban populations are at higher risk of NCDs such as CVD and T2DM compared to their rural counterparts [7,8].

Communicable diseases have been the focus of many health promotion programs in PNG, aimed at delivering education to increase awareness of infectious diseases and reduce the burden of disease [9,10,11,12]. This included initiatives such as the Women and Children’s Health Project carried out in PNG between 1998 and 2004 [13], as well as other local health campaigns focusing on TB and malaria [9,10]. The National Policy on Health Promotion for PNG aims “to empower individuals and communities thereby enabling them to control the status of their own health”; however, the policy recognised a gap in health promotion activities specifically for ‘Healthy Islands’—a vision encouraging preventive measures for health promotion and health protection [14].

There are renewed efforts from the PNG government as part of the 2021–2030 National Health Plan and ‘Healthy Islands’ concept to focus on health promotion, including nutrition promotion [15]. The plan prioritises, as part of its strategies for preventing and reducing the morbidity and mortality of NCDs, increasing population awareness so that individuals can make more informed decisions about their health and engaging in collaborations with stakeholders to implement nutrition programs [15]. Furthermore, with survey findings revealing smoking, being overweight or obese, and impaired fasting glycemia to be among the common NCD risk factors in PNG for those aged between 15 and 64 years [16], health promotion interventions targeted at lifestyle modification, including diet and exercise could support the management and reduction of NCD-risk.

Therefore, this scoping review aimed to scope the body of literature for health and nutrition promotion programs that have been implemented in PNG, including both communicable diseases and NCDs, and determine the enablers and barriers to these programs [17]. These findings could then be used to inform future health promotion programs, particularly for preventing and managing NCDs in PNG.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The protocol for this scoping review was registered on https://osf.io/pvkg8/ (accessed on 18 June 2024). The findings are reported in accordance with the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews, and Joanna Briggs Institute updated methodological guidance for scoping reviews [18,19].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies.

2.2.1. Type of Evidence Sources

All primary study designs, government reports, and websites were included. Conference abstracts, theses, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, policy papers, expert opinions and non-peer-reviewed articles were excluded. Studies were limited to human studies, and language was restricted to English. There was no date of publication limit applied to capture all health promotion programs that had been conducted in PNG over time.

2.2.2. Participants and Context

All ages, regions, and settings of PNG (primary health care, schools, workplaces, churches or community centres) were included. Studies based on alcohol or drug rehabilitation, live-in facilities, and facilities for diagnosed mental illness were excluded.

2.2.3. Concept

Primary health promotion interventions that focused on the prevention of NCDs, including over and undernutrition, infectious diseases including malaria, TB and sexually transmitted diseases including HIV and the Human papillomavirus (HPV), as well as sexual health were included. While it is recognised that health promotion policies such as healthy catering policies, no smoking policies, environmental policies, or urban design modification will often support health promotion interventions, these were excluded from this review, given the focus placed on interventions. Papers solely reporting on recommendations for future health programs were excluded.

2.3. Information Sources

Relevant studies were identified through a comprehensive literature search using the following electronic databases: Medline, Embase, Global Health, and Scopus. Grey literature searches were conducted by using the advanced search function on Google Scholar (limited to the first 200 records). A citation search of articles included for full-text screening was performed to scan for additional documents.

2.4. Search Strategy and Terms

The review team drafted the search strategy in consultation with an experienced university librarian (M.C.). See Supplementary Table S1 for the final MEDLINE search strategy. The final search for all databases was conducted in March 2023.

2.5. Study Selection Process

All documents retrieved from the search were exported to EndNote20 citation management software to remove duplicates. The citations were imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) to be independently screened by two reviewers (P.T. & R.G.) in accordance with the eligibility criteria. The study selection process was conducted in two stages. The first stage involved independent screening of titles and abstracts by two reviewers against the inclusion criteria. The second stage involved independent screening of full texts by two reviewers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For both stages, any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (J.C., A.D. or B.P.).

2.6. Data Extraction and Charting Process

Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers (P.T. & R.G.) using a standardised data charting form for scoping reviews [18]. The following data were extracted: first author and year, program/intervention name, aim, targeted communicable disease or NCD, setting, participants, study design, a brief description about the program, the Ottawa Charter key action areas for Health Promotion (i.e., create supportive environments for health, strengthen community action for health, develop personal skills, and reorient health services) [14,20] addressed by the program, enablers and barriers to the programs and the main findings.

2.7. Synthesis of Results

The results were presented in tabular form, with an accompanying narrative summary to describe the results in relation to the objectives of the scoping review.

3. Results

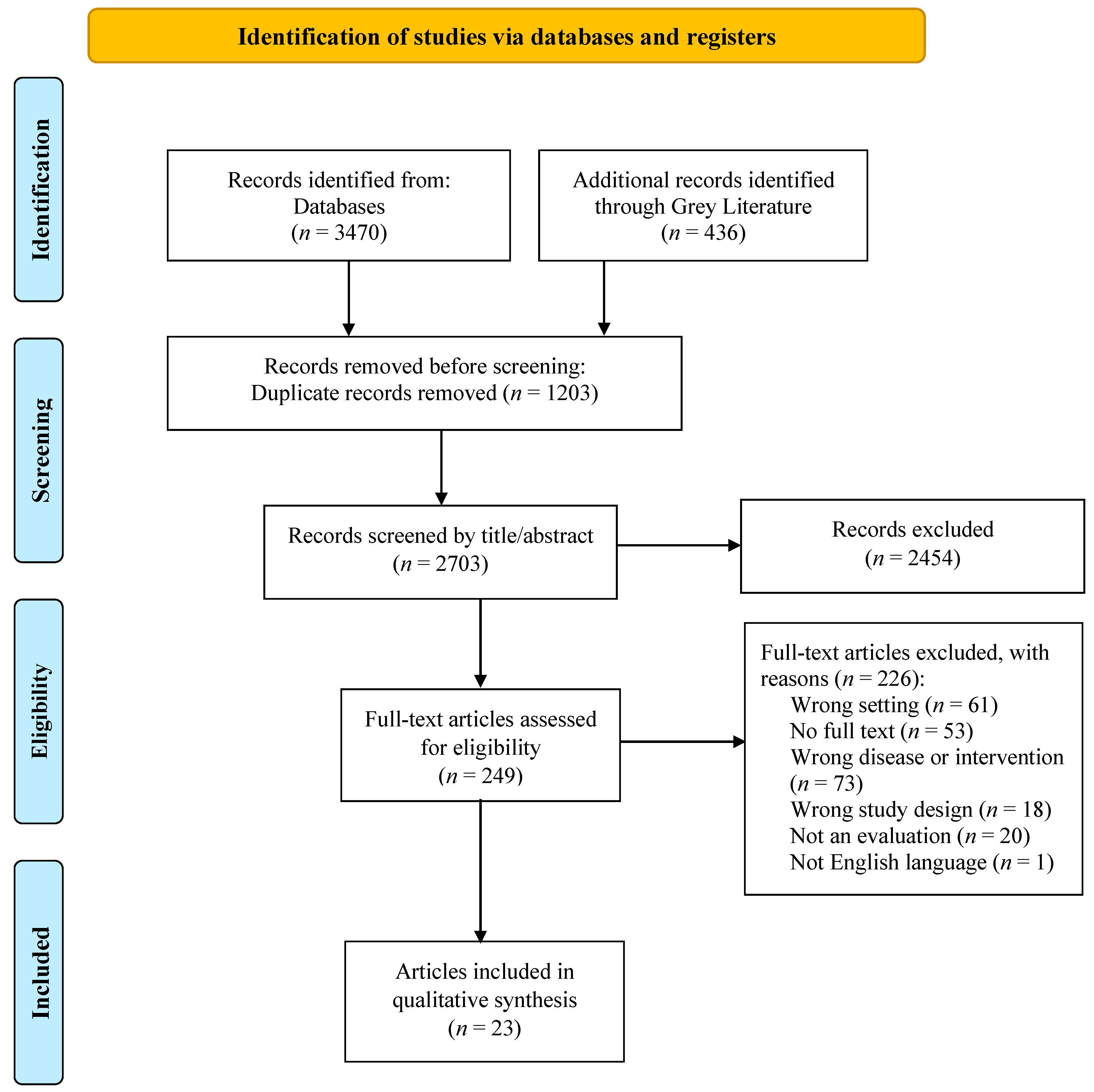

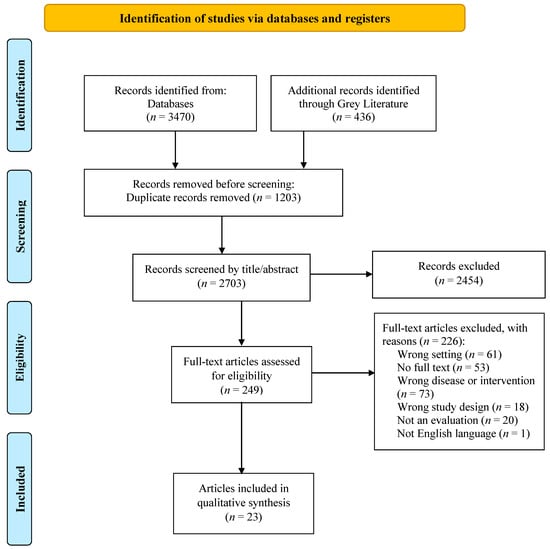

This scoping review yielded a total of 3906 records from databases, grey literature and citation searching. Following the removal of 1203 duplicates, 2703 records were screened by title and abstract. A total of 249 records underwent full-text screening, and 226 records were excluded with reason, resulting in a total of 23 articles meeting the inclusion criteria and included in this review. The PRISMA-ScR flow diagram illustrates the selection process (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR flow diagram of record identification and study selection for a scoping review on health and nutrition promotion programs conducted in PNG [21].

3.1. Program Selection and Characteristics

Study and program characteristics are described in Table 2. Of the total 23 articles included, there were 17 peer-reviewed articles [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], five grey literature reports [39,40,41,42,43], and one book chapter [44]. Five were quantitative studies [23,29,30,39,40], 13 were qualitative [22,24,25,28,31,32,33,34,35,36,42,43,44], and five were mixed-methods [26,27,37,38,41]. The included publications (1996 to 2022) spanned over a period of 26 years.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies and health and nutrition promotion programs in PNG.

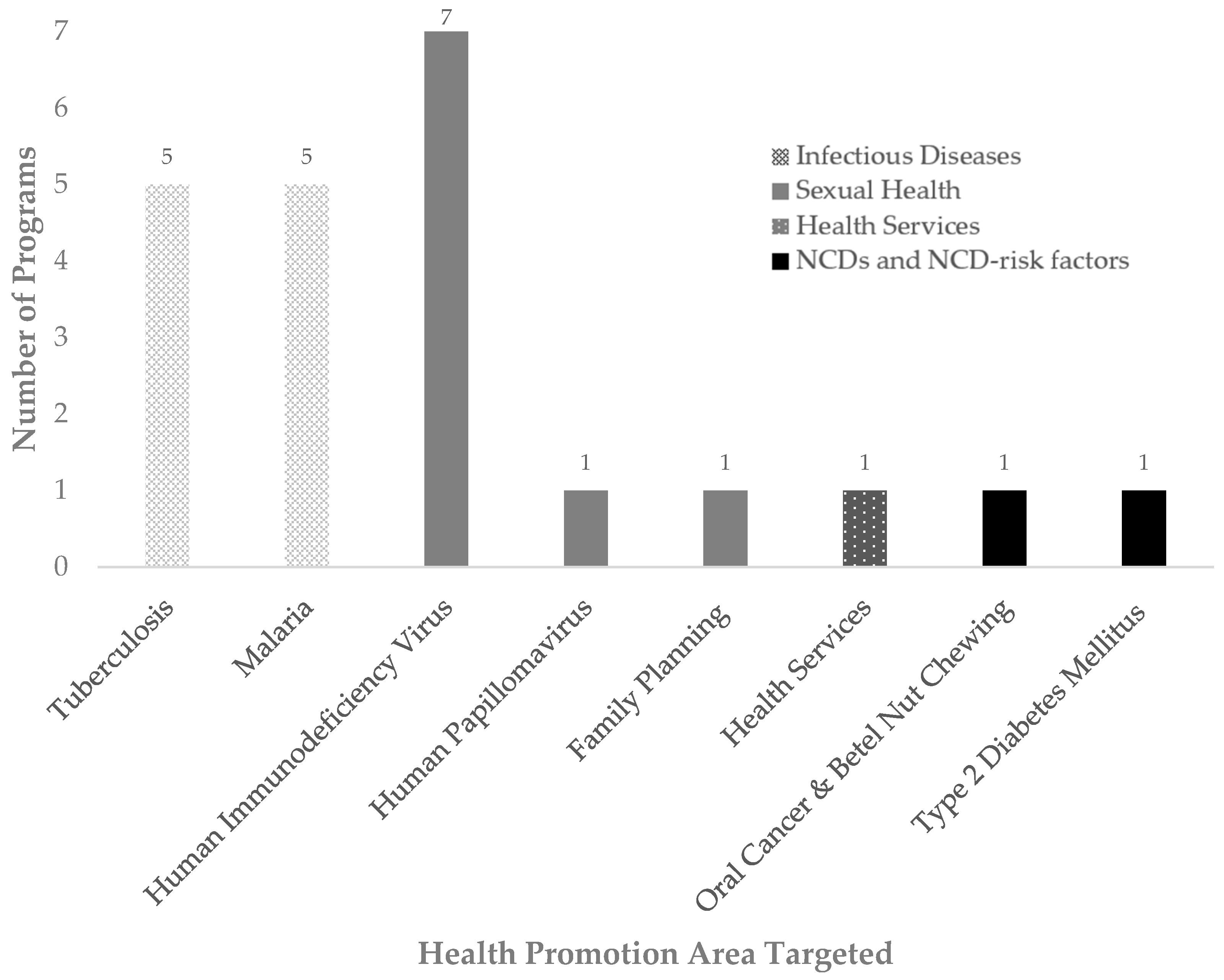

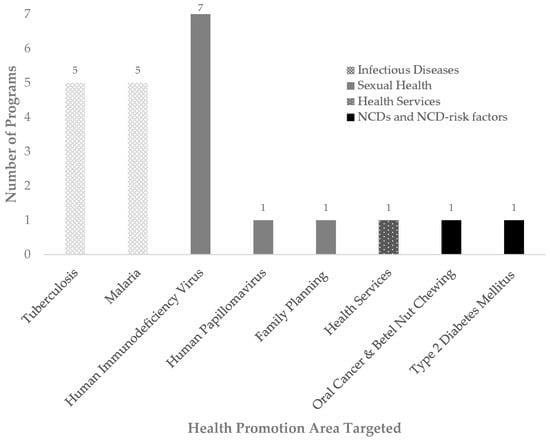

A total of 22 programs focusing on health promotion interventions in PNG were identified from 23 articles. Of these 22 programs, 19 programs targeted communicable diseases (see Figure 2). Ten programs targeted infectious diseases, TB (n = 5) [22,23,39,40,41] and malaria (n = 5) [24,25,26,27,28]. Nine programs targeted sexually transmitted diseases and sexual health, HIV (n = 7) [29,30,31,32,33,42,43,44], with three specifically targeting parent-to-child HIV transmission [29,30,31], HPV (n = 1) [34], and one on family planning (n = 1) [35]. One health promotion program addressed health services [36]. Two programs targeted NCD-risk factors and NCDs, namely betel nut chewing [37] and a nutrition promotion program on T2DM [38].

Figure 2.

The different health promotion areas targeted by the programs.

Four programs took place at a national level across PNG [22,23,26,35], and nine programs were delivered at a community level across PNG [32] and in different regions of PNG, including the Highlands [24,25,33,39,43,44], Highlands, Momase and Southern PNG [42], and New Guinea Islands [38]. Eight programs were in the health setting, targeting health workers or people attending hospitals and/or health service clinics or facilities across PNG [28,36] as well as specifically in New Guinea Islands [40], Southern [41], Highlands [27,29], Southern and Highlands [30,31], and Momase and Highlands [34]. One program was in the school setting (Momase [37]).

3.2. Program Aims

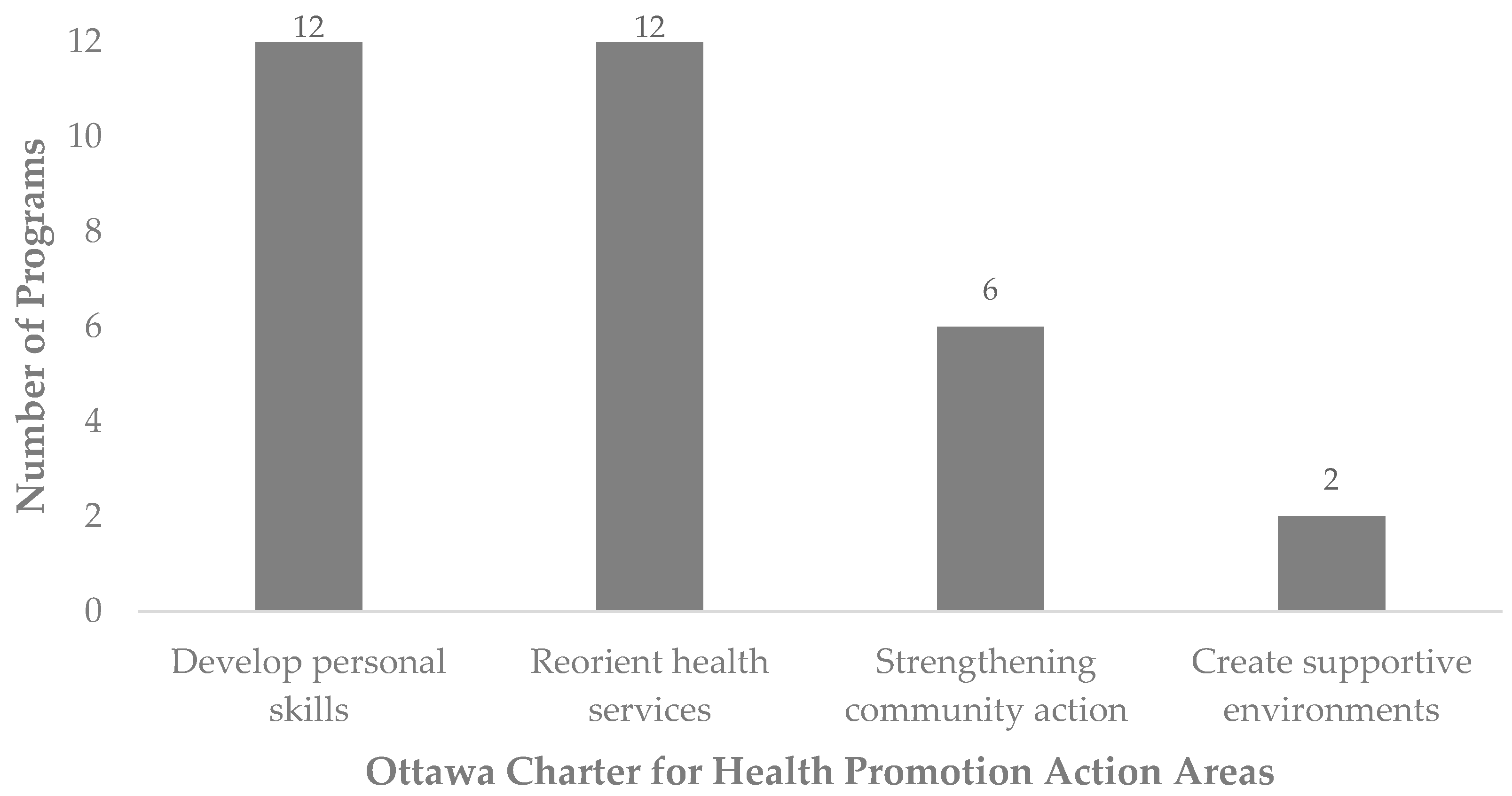

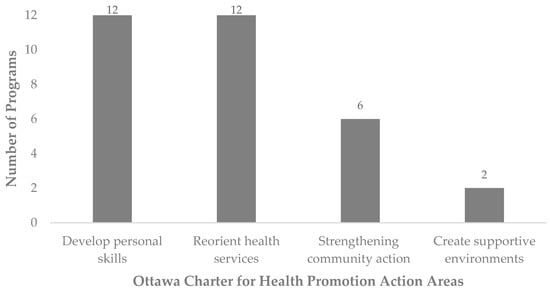

The programs aimed to either control, prevent or reduce the disease burden of TB, malaria, HIV, HPV, betel nut chewing and T2DM through different health-promoting strategies, which could be categorised by the following key action areas of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion action areas targeted by the programs.

3.2.1. Develop Personal Skills

Twelve programs focused on developing personal skills. Ten programs incorporated a component of training, education or awareness raising as a strategy to spread knowledge about the disease for increased prevention, screening or treatment [24,25,33,34,37,38,39,40,42,43,44], and three programs focused on the provision of counselling and care [29,30,39].

3.2.2. Reorient Health Services

Twelve programs addressed the health promotion action area of reorienting health services. Two programs included training health workers to provide better care or education to the public [34,40]. There was one training program for health workers to become field epidemiologists to strengthen the public health workforce and health systems [36]. Seven programs involved screening, treatment or diagnosis, including surgical or medication programs [22,23,29,30,31,35,41]. There were two programs that used technology for malaria control, such as m-health for health data surveillance or text messaging reminders to healthcare workers [27,28].

3.2.3. Strengthening Community Action

Seven articles reporting on six programs were targeted at strengthening community action. This was observed in the mobilisation of community members to take action, either through working together to create health-promoting messages, training for diagnosis and treatment, or peer counselling for other community members [22,24,25,32,39,43,44].

3.2.4. Create Supportive Environments

Two malaria programs sought to ‘create supportive environments’ by providing bed nets for malaria prevention [25,26].

3.3. Enablers to Health and Nutrition Promotion Program

Factors that enabled the program were cultural appropriateness, community involvement, educators, resources, staff and funding, and health service delivery, described below and in Table 3.

Table 3.

Key findings of the included studies and health and nutrition promotion programs in PNG.

3.3.1. Cultural Appropriateness and Adaptation

A common characteristic influencing program effectiveness was understanding cultural context to ensure cultural appropriateness [24,25,29,32,33,34,35,38,44]. In the Batri Village Bed Net Initiative for the provision of nets to a rural community, the villagers felt respected as the program was inclusive and authentic, which could be attributed to the incorporation of language-translation tools and prior communication with village elders [25]. In an HIV prevention program, local communities were engaged in a bottom-up approach to build capacity and support local knowledge, storytelling, interests, customs, and languages in order to achieve changes in attitudes, behaviours, and social norms [32]. In another education program for HIV, village leaders were involved in decisions about the education session to determine the appropriateness of the content for community cooperation and enthusiasm [33].

Improved knowledge of T2DM was seen after carrying out a nutrition promotion program that was culturally sensitive and interactive and utilised a storytelling model tailored to Indigenous communities in the New Guinea Islands [38]. An interpreted supported translation into a local dialect. The program involved a ‘Sugarman’ presentation designed to raise awareness about choosing local non-processed foods commonly consumed by the Bougainvillean population over high-caloric Western foods and their impact on health, particularly in relation to T2DM. The program emphasised T2DM prevention and management through healthy lifestyle choices such as exercise, a healthy diet, and not smoking.

3.3.2. Community Involvement

Another factor in programs with positive impact or community acceptability was involving the community in the programs in different ways. Community involvement in helping to counsel and educate other members of the community contributed to reduced loss to follow-up for TB care [39]. Training women for medicine storekeeping and quality assurance of diagnosis in a community with high rates of malaria helped to reduce the number of cases [24]. Community participation in the innovative creation of health messages and interventions through different media, including visual and digital media, helped to create localised meaning by tailoring the content to their own culture, language and literacy levels [32,43,44]. This allowed the communities to be more readily accepting of the messages.

3.3.3. Educators

In an education program, it was important to train educators to be flexible in different teaching methods, responsive to community concerns, and able to foster a comfortable environment when talking about potentially embarrassing topics, as this was effective in ensuring participant understanding and dialogue [33]. Healthcare workers who were knowledgeable and understanding when providing education created a trusting patient-provider relationship, which was a major factor in the effectiveness of the HPV program [34].

3.3.4. Resources, Staff and Funding

Mobilisation of funding and resources, including technology and medicines, contributed to the effectiveness of TB and HIV treatment programs [23,30,31,41].

3.3.5. Leadership and Partnership Collaboration

Strong government commitment or leadership in conjunction with effective collaborations between technical partners, NGOs, community and government contributed to increased treatment rates, training and research programs, particularly with regards to increased sustainability of the program [23,35,36,41].

3.3.6. Health Service Delivery

Health workers reported that the incorporation of mobile health (mHealth) technologies, like mobile phone text message reminders and mHealth apps linked to health professional platforms via geographical coding, were helpful in reinforcing health service delivery messages and monitoring outbreaks [27,28]. mHealth reminders were also useful for reminding patients of their appointments to improve patient compliance with attending TB treatment [40]. Decentralisation of care for TB health services to the district level increased screening and reduced unfavourable treatment outcomes [40].

3.4. Barriers to Health and Nutrition Promotion Program

Lack of cultural appropriateness; resources, staff and funding; leadership and health service delivery; and lack of behaviour change campaigns were several common characteristics that emerged as barriers to the programs (see also Table 3):

3.4.1. Lack of Cultural Appropriateness and Adaptation

Some programs did not consider language and cultural context, which caused problems in a low literacy setting. For example, print media for HIV awareness were in English, yet there was an overwhelming preference for Tok Pisin to be used in most covered regions [42]. In Milne Bay Province, there was a preference for one or two of the four dominant tok plus languages (local language) [42]. Knowledge outcomes of a betel nut chewing education program were not significantly improved for primary school students, likely due to English being a second language for most [37].

3.4.2. Resources, Staff and Funding

A common dissatisfaction with treatment programs was a lack of sufficient supply of medications in health services [22,29]. Additionally, lack of treatment supervision due to a lack of staff or service scope led to unfavourable treatment outcomes or increased loss to follow-up rates [22,31]. Lack of resource supplies such as bed nets led to unfavourable outcomes for malaria [26].

3.4.3. Leadership and Health Service Delivery

The lack of central leadership and integration of health services led to poor delivery of health service-based programs [31,35].

3.4.4. Cost

The cost of attending health services, including transport and treatment costs, contributed to a loss in follow-up rates, particularly for those living in rural areas [31].

3.4.5. Lack of Behaviour Change Campaigns

A resource provision program for mosquito bed nets did not see favourable outcomes as it was not accompanied by behaviour change or awareness campaigns to encourage increased use of the bed nets [26].

3.5. Program Outcomes

3.5.1. Tuberculosis

Programs that incorporated training, education, counselling, and awareness were generally able to increase screening and retention in care. However, this did not necessarily lead to significant improvement in health outcomes [39,40]. The national TB treatment programs had mixed findings across PNG [22,23,41].

3.5.2. Malaria

Training community members to diagnose and treat malaria for others in the same community, as well as community-level net provision programs that were integrated with education sessions, helped to lower malaria mortality and morbidity [24,25]. The nationwide net provision program also increased ownership and usage of nets to prevent malaria [26].

3.5.3. Sexually Transmitted Diseases

For parent-to-child HIV programs, there was improved HIV-free survival with time as programs incorporated more resources and a more family-centred approach; however, loss to follow-up rates remained unacceptable, and efforts towards increasing health service accessibility are necessary [29,30,31]. A community-level program involving social mobilisation for HIV demonstrated promising signs of changing community attitudes and behaviours [32]. HIV education and awareness programs through visual media or education sessions were positively received, with most participants understanding the importance of screening, changing their attitudes towards people living with HIV and identifying individual preventative behaviours [33,42,43,44]. Health outcomes for HIV programs were not reported [29,30,31,32,33,42,43,44].

The national no-scalpel vasectomy program for family planning had mixed outcomes throughout the country [35].

The pilot HPV screening and treatment program showed a high level of acceptability for PNG women, which could potentially increase future screening uptake [34].

3.5.4. Non-Communicable Diseases

The education program for school children about NCD risk factors (betel nut chewing) showed an improved understanding of the topics for most participants; however, there was no significant change in knowledge of betel nut chewing for primary school children [37]. The Sugarman presentation improved understanding of the causes, symptoms, and prevention of T2DM among communities, with the greatest improvement being in communities where there was initially poor knowledge about T2DM [38]. However, health outcomes, such as anthropometry or biochemistry, were not measured or reported for T2DM or betel nut chewing [37,38].

4. Discussion

This scoping review is the first to synthesise evidence from 22 health and nutrition promotion programs (23 articles) in PNG and to identify factors that were enablers and barriers to these initiatives. Most health promotion programs (n = 20) in this review targeted communicable diseases, particularly infectious diseases. There was only one health promotion program targeting NCD risk via betel nut chewing and oral cancer [37] and one nutrition promotion program for T2DM [38]. Both programs demonstrated improvements in participant awareness of strategies for preventing these NCDs, though the impact on health was not measured. Enablers of health promotion initiatives included cultural appropriateness, mobilising community action and using mHealth technologies to decentralise health services. On the other hand, many programs were unsustainable or resulted in unfavourable outcomes due to lack of resources, funding and ineffective leadership for sustained implementation. The paucity of health and nutrition promotion programs targeting diet and modifiable lifestyle risk factors highlights the urgent need to prioritise the delivery and evaluation of NCD-related health promotion.

Directly addressing the NCD burden and targeting health priorities has been emphasised in the PNG National Health Plan 2021–2030 and policy directions [15]. The priority of revitalising the Healthy Islands approach for health promotion and prevention efforts through healthy lifestyle behavioural modifications to support better health [15] is also timely. While in our review, there were few health and nutrition promotion programs in PNG targeting NCDs, enablers to health promotion programs targeting communicable diseases could be adopted into future health and nutrition promotion programs for NCDs. Foundational to Healthy Islands is an underpinning of community participation and empowerment activities [14]. For community-level programs, understanding contextual elements is essential to the development of effective behaviour change interventions [45]. Health programs in PNG that incorporate active community involvement to ensure cultural appropriateness, better understanding of the cultural and social milieu as well as cooperation and collaboration between participants and educators or researchers, demonstrated positive outcomes [25,32,33,38,43,44]. By providing information in local languages or the common language, Tok Pisin, health promotion programs can overcome language and literacy barriers and ensure that messages are culturally appropriate and relevant. Particularly, the involvement of village leaders or influential community figures in the decision-making process may help to build trust, and therefore, communities may be more readily accepting of the health messages [33]. This is especially important in settings such as PNG, where there can be a distrust of ‘outsiders’ when conducting health programs [46]. Hence, developing interventions and health promotion programs that are embedded in co-design with communities will ensure that delivery, ownership and acceptance of these initiatives are sustainable and affordable. A holistic approach to health, addressing physical, mental, social and spiritual well-being, is essential when working with communities in PNG. Being a Christian nation, churches and religious leaders are highly respected and can, therefore, be an integral component in allowing health promotion programs to provide education, spread health information, and deliver health care services to communities [47,48]. The importance of including churches and religious leaders is also highlighted in the framework for Pacific health research and from work in Pacific communities in New Zealand [49].

Analyses have suggested that PNG has experienced slower effects of the nutrition and epidemiological transition [50,51] compared to other Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs). However, poor data precludes robust estimates of NCDs in PNG and larger population numbers in PNG relative to other PICTs, which means the nutrition transition impacts a wider subset of the Pacific population. While there are few health and nutrition promotion programs for NCDs in PNG, lessons could be drawn from health promotion programs that are available and implemented in other PICTs. For example, a Fijian health promotion initiative, the Healthy Youth Healthy Communities project, targeted adolescent obesity and NCD prevention through improving nutrition and physical activity behaviours [52]. The program considered holistic elements of the Ottawa Charter’s key action areas through school-based nutrition policies, education and role play, social marketing, the creation of supportive environments through water fountain installation, community capacity building, empowerment, and collaboration. Outcomes revealed a reduction in body fat percentage but mixed behaviour change results [53]. In a systematic review by Palu et al. [54], lifestyle-based health and nutrition promotion programs among populations in PICTs (though predominantly conducted in New Zealand) were found to be efficacious for weight loss. Particularly, the study also emphasised the importance of culturally conducive approaches, community action, peer support, and behaviour change strategies as important factors in intervention design, which is consistent with the enablers from programs targeting communicable diseases identified in our review.

The PNG government have acknowledged that adopting digital health interventions is an innovative means for supporting citizens in improving their education with mobile technologies, such as smartphone applications (apps) and e-learning [15]. In Western countries, digital platforms and mHealth apps have been found to have potential as nutrition promotion tools for modifying lifestyle behaviours like physical activity and sedentary time, as well as improving nutritional knowledge and self-efficacy [55]. They have also been found to support the management of NCDs [56,57,58] and NCD-risk factors [59]. The potential of mHealth technologies in developing countries or LMIC has also been documented for improving health outcomes for infectious diseases and maternal health [60], for health promotion of communicable diseases and NCDs [55] and effective in promoting physical activity and healthy diets [61]. Evidence of the adoption of mHealth technologies into health promotion programs for communicable diseases was observed in this review. Three programs incorporated mHealth technology (text messaging and apps) to support and reorient health service delivery, which improved patient attendance at health appointments, aided health workers in education about treatment and enabled the monitoring of disease outbreaks via geographical coding [27,28,40]. This is consistent with another scoping review by Van Olmen et al. [62], which reported that across LMIC, text messaging was the main mHealth medium applied, particularly for patient-centred NCD self-management. However, notably, in Van Olmen et al.’s review, no PICTs were included as part of the LMIC [62]. When examining lifestyle intervention for weight loss and NCD-risk factors in PICTs, no studies included any mHealth technologies [54]. Therefore, there is potential for PNG health and nutrition promotion programs to adopt mHealth technologies. However, some key considerations when using mHealth technologies in PICTs and PNG are improving digital and digital health literacy, device accessibility, internet connectivity and infrastructure for mHealth use and developing strategies to maintain ongoing engagement with mHealth technology over time to facilitate behaviour change.

Partnerships with local governments, non-governmental organisations, and other partnering countries for leadership to secure funding and human resources are essential for ensuring that health promotion programs are sustainable and successful. It is important to consider that in PNG, foreign aid from other countries or non-government organisations is a major funding source for health promotion activities. Taking vaccination programs in PNG as an example, which have been successful, UNICEF has supported the PNG government by purchasing vaccines and helping to maintain the cold chain system by working with the 22 provincial health authorities to deliver standardised programs across the country [63]. Australian Aid (AusAID) likewise has supported the vaccination of close to 1 million children in PNG since 2009 [64]. World Health Organisation (WHO) also supports the PNG government by providing mostly technical assistance [65]. Together, a unified effort from various sectors, reinforced by funding and resource allocation, is therefore crucial for the sustainable delivery of health promotion programs.

The results of this review indicated that health promotion initiatives only addressed one or two of the action areas outlined in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Comprehensive approaches to health promotion are therefore required to ensure that disease prevention and improving health and quality of life are addressed at all levels, individual, community, and national, to support healthy behaviours and provide an enabling environment. Building healthy public policies that drive health and nutrition promotion programs is an area requiring further investigation, with a particular focus on the evaluation of the impact of these policies. Evaluations of PNG national policies and strategic plans have been undertaken for TB and malaria control, NCD preventative policies have been monitored, and nutrition has even been improved [66,67,68,69]. The evaluation of NCD policies in PNG found that food and healthy eating policies, in particular, were underdeveloped, while preventative policies around tobacco, alcohol and physical activity had a higher presence and strength of implementation [68]. The evaluation of PNG’s National Nutrition Policy Strategic Action Plan (2018–2022) [70] found that the main challenge of implementing the nutrition policy and action plan included the absence of political and senior management leadership, lack of funding, resources and staffing, leading to limited roll-out of activities related to this policy and plan as well as limited monitoring and evaluation [69].

The barriers to policy implementation are consistent with many of the barriers to health promotion program implementation in PNG, as seen in this review. Therefore, it is suggested that for health promotion policy and strategy implementation, there must be a high-level political commitment to raising awareness among politicians about the importance of emerging health issues [69,71]. These challenges may be a reflection of structural health system issues since the decentralisation of health service delivery to the provincial level following PNG’s independence in 1975 [47]. This is consistent with a recent case study of the PNG healthcare system, which stated ineffective governance, systemic issues with provincial financing, insufficient resources and health workers, and deteriorating infrastructure as some of the key barriers to primary health care [47]. A coordinated and collaborative approach with political leadership at the national and sub-national levels, health promotion and nutrition committees, advisory groups and stakeholders are thus required for advocacy and to support the implementation of health and nutrition promotion activities at community-based provincial and district levels and to subsequently generate evidence for the policies themselves [69].

4.1. Future Directions and Recommendations

Knowledge about nutrition and NCDs in the community is poor [48]. Therefore, future recommendations to combat the emerging health issues in PNG, as described in this review, include the development of health promotion programs targeting nutrition and physical activity. Programs should adopt a systematic and multilayered approach targeting individuals, communities and the wider public. This type of collective approach has been found to be effective in research on chronic diseases and behaviour change with Pacific communities [49] and emphasised by Pacific health research guidelines [72]. Health promotion programs should focus on long-term sustainability through multi-faceted strategies that include education components and the involvement of key community figures in the development process. For instance, programs aimed at increasing education and awareness, such as the T2DM program in Bougainville, should not only seek to increase the participants’ knowledge of diabetes [38] but also be inclusive of families and relatives and the wider community, such as by utilising church groups.

Community-based participatory research approaches should be used in the design of future health and nutrition promotion programs so that health messages and activities can be co-designed with communities. Drawing from successful COVID-19 vaccination, immunisation and family planning activities programs in PNG, the involvement of village or community leaders and participants in health promotion activities is fundamental to the adoption and uptake by communities. Considering the culturally diverse landscape of PNG, an emphasis should be made in all health and nutrition promotion program planning to ensure cultural appropriateness and adaption of program activities to each specific region and local community, for example, using the language for program delivery and resources, or tailoring the types of foods recommended in nutrition promotion program, given the variability in diets across the different PNG regions [73]. Furthermore, in a culture where there are strong oral traditions, greater incorporation of cultural storytelling into programs may also enhance future program outcomes in this context [74], as there was only one study in this review which utilised this approach [38].

Based on our findings, it is recommended that funding and aid bodies (e.g., AusAID, Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, UNICEF, WHO) should also ensure appropriate cultural considerations are evidenced as part of their funding criterion in aid and project work undertaken in PNG and the Pacific more broadly. Locally, governments should consider continued support through funding for the expansion or ongoing delivery and tailoring or modification of successful programs, such as education programs that improve health literacy in specific social and cultural contexts throughout PNG, particularly as the population of PNG has low literacy levels around the emerging NCDs [75].

Drawing from obesity prevention programs in similar settings, in conjunction with health promotion programs that empower the community, it is critical to also implement and monitor compliance with health and nutrition policies, such as PNG’s 2021-2030 National Health Plan. This could include more widespread dissemination of the Pacific Guidelines for Healthy Living [76,77] through channels such as schools, churches, workplaces, or health services, which may improve population awareness of methods for reducing NCD risk. The guidelines address ten areas, including a healthy diet, physical activity, betel nut chewing and other drugs, and community involvement. These resources would also need to be embedded with further behaviour change initiatives and in-person programs run in local communities to make the public more aware of the resources and how to practically implement them in everyday life. Furthermore, multi-sectorial and muti-faceted approaches that address structural factors of rapid urbanisation and marketing of unhealthy foods will also encourage preventative behaviours and potentially better health outcomes for the people of PNG [78].

With the inconsistency in measures of program outcomes reported across the studies in this review, it is also pivotal that future studies include consistent reporting of methodology, including data collection and analysis and intervention outcomes, such as through the use of standard reporting guidelines via the Equator Network [79]. It is necessary to move beyond short-term assessments of program outcomes towards comprehensive, longitudinal evaluations that measure the effectiveness of these health promotion interventions as well as their impacts on long-term behaviour change and health outcomes. Process evaluation of program implementation, including reach, adoption, fidelity of intervention, cost-effectiveness, scalability and community satisfaction, are also warranted for all health promotion programs to ensure sustainability and maintenance of these efforts.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this scoping review includes the wide range of information sources, including databases and grey literature. This review was the first to examine health and nutrition promotion programs for communicable diseases and NCDs in PNG. A key limitation is that health and nutrition promotion programs that may have been implemented in PNG but not formally evaluated or recorded in reports or the scientific literature were not captured by this scoping review, which may limit findings, particularly those of newer programs targeted at NCDs. Evidence-based program planning, along with building local research capacity within PNG, could address and mitigate this issue.

5. Conclusions

This review has identified an urgent need for health and nutrition promotion programs to target preventative lifestyle health behaviours and NCDs for individuals and communities. This review also provides evidence to support strategies in health and nutrition promotion programs such as cultural appropriateness, mobilising community action and personal skills development through education and training. Effective collaboration through gaining leadership commitment to sustained funding and resources and strengthening international and organisational partnerships will help to activate support for any future programs or policies. Future research should focus on comprehensive, longitudinal evaluations of current or future programs to better the health outcomes of the people of PNG.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu16131999/s1, Table S1: Medline Search Strategy [19].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and B.P.; methodology, A.D., J.C., P.T., R.G., A.R., M.A.-F. and B.P.; formal analysis, J.C., P.T. and R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C., P.T. and R.G.; writing—review and editing, A.D., A.R., M.A.-F., S.P., R.O. and B.P.; supervision, A.D., J.C., A.R., M.A.-F. and B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This work was submitted to the University of Sydney to partially fulfil the requirements of the Master of Nutrition and Dietetics by the two first authors Phyllis Tran and Ryley Gronau. The authors wish to acknowledge Monica Cooper, an academic liaison librarian at the University of Sydney, for her support in the development of the search strategy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Papua New Guinea Country Brief. Available online: https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/papua-new-guinea/papua-new-guinea-country-brief (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Pham, B.N.; Jorry, R.; Silas, V.D.; Okely, A.D.; Maraga, S.; Pomat, W. Leading causes of deaths in the mortality transition in Papua New Guinea: Evidence from the Comprehensive Health and Epidemiological Surveillance System. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 52, 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Anderson, I.; Burton-Mckenzie, E.-J. The value of lost output and cost of illness of noncommunicable diseases in the Pacific. Health Policy OPEN 2022, 3, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vengiau, G. Nutrition Transition in Papua New Guinea (PNG): An Assessment of the Nutrition Transition for Three Diverse Populations, Including the Contributing Factors, Food Insecurity, and Health Risks. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ACIL Tasman Pty Ltd. PNG LNG Economic Impact Study: An Assessment of the Direct and Indirect Impacts of the Proposed PNG LNG Project on the Economy of Papua New Guinea; ACIL Tasman Pty Ltd.: Double Bay, Australia, 2009; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Amuna, P.; Zotor, F.B. Epidemiological and nutrition transition in developing countries: Impact on human health and development. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2008, 67, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kende, M. Superiority of traditional village diet and lifestyle in minimizing cardiovascular disease risk in Papua New Guineans. PNG Med. J. 2001, 44, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, T.; Umezaki, M.; Ohtsuka, R. Influence of urbanisation on physical activity and dietary changes in Huli-speaking population: A comparative study of village dwellers and migrants in urban settlements. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 85, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemer, S. Global Health, Tuberculosis and Local Health Campaigns: Reinforcing and Reshaping Health and Gender Inequalities in Lihir, Papua New Guinea. In Unequal Lives: Gender, Race and Class in the Western Pacific; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2021; pp. 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, E.; Hetzel, M.W.; Clements, A.C.A. A review of malaria epidemiology and control in Papua New Guinea 1900 to 2021: Progress made and future directions. Front. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, 980795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worth, H. HIV Prevention in Papua New Guinea: Is it working or not? World J. AIDS 2012, 2, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep Thi Ngoc, N.; Kate, T.S.; Adam, K.; Glen, M.; John Walpe, B.; Joseph, K.; Pamela, J.T.; Steven, G.B.; Marion, S.; John, K.; et al. Towards the elimination of cervical cancer in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: Modelled evaluation of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of point-of-care HPV self-collected screening and treatment in Papua New Guinea. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwell, H.E.; Barclay, L. Outcome evaluation of community health promotion intervention within a donor funded project climate in Papua New Guinea. Rural Remote Health 2009, 9, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papua New Guinea Ministry of Health. National Policy on Health Promotion for Papua New Guinea. Available online: https://www.health.gov.pg/pdf/healthpromotionp.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Government of Papua New Guinea. National Health Plan 2021-2030 Policies and Strategies. Available online: https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/article/downloads/NHP_Volume_1A_Policies_and_Strategies_0.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Papua New Guinea NCD Risk Factors STEPS REPORT 2007–08; World Health Organisation: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2014; pp. 1–153.

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Health Promotion. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/first-global-conference/actions (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, J.; Poka, H.; Kumbu, J.; Pomat, N.; Ripa, P.; Tefuarani, N.; Vince, J.D.; Duke, T. The crisis of tuberculosis in Papua New Guinea--the role of older strategies for public health disease control. Papua New Guin. Med. J. 2012, 55, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- van Maaren, P.; Tomas, B.; Glaziou, P.; Kasai, T.; Ahn, D. Reaching the global tuberculosis control targets in the Western Pacific Region. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkot, C.; Naidi, L.; Seehofer, L.; Miles, K. Perceptions of incentives offered in a community-based malaria diagnosis and treatment program in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 190, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, J.; Ako, W.Y. Empowering the initiation of a prevention strategy to combat malaria in Papua New Guinea. Rural Remote Health 2007, 7, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hetzel, M.W.; Gideon, G.; Lote, N.; Makita, L.; Siba, P.M.; Mueller, I. Ownership and usage of mosquito nets after four years of large-scale free distribution in Papua New Guinea. Malar. J. 2012, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumop, S.F.; Bullen, C.; Whittaker, R.; Betuela, I.; Hetzel, M.W.; Pulford, J. Improving Health Worker Adherence to Malaria Treatment Guidelines in Papua New Guinea: Feasibility and Acceptability of a Text Message Reminder Service. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosewell, A.; Makita, L.; Muscatello, D.; John, L.N.; Bieb, S.; Hutton, R.; Sundar, R.; Shearman, P. Health information system strengthening and malaria elimination in Papua New Guinea. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmone, A.; Bomai, K.; Bongi, W.; Frank, T.D.; Dalepa, H.; Loifa, B.; Kiromat, M.; Sarthak, D.; Franke, M.F. Partner testing, linkage to care, and HIV-free survival in a program to prevent parent-to-child transmission of HIV in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 24995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly-Hanku, A.; Nightingale, C.E.; Minh Duc, P.; Mek, A.; Homiehombo, P.; Bagita, M.; Nankinga, J.; Vallely, A.; Vallely, L.; Sethy, G.; et al. Loss to follow up of pregnant women with HIV and infant HIV outcomes in the prevention of maternal to child transmission of HIV program in two high-burden provinces in Papua New Guinea: A retrospective clinical audit. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tynan, A.; Vallely, L.; Kupul, M.; Neo, R.; Fiya, V.; Worth, H.; Kariwiga, G.; Mola, G.D.L.; Kaldor, J.; Kelly-Hanku, A. Programmes for the prevention of parent-to-child transmission of HIV in Papua New Guinea: Health system challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, e367–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, C.; Bola, L.; Bundu, F.; Bunemiga, C.; Gustafsson, B.; Kaviani, N.; McSmith, D.; Pakure, R.; Raka, D. Putting the community at the center of measuring change in HIV prevention in Papua New Guinea: The Tingim Laip (Think of Life) Mobilisation. Pac. Health Dialog 2007, 14, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lupiwa, S.; Suve, N.; Horton, K.; Passey, M. Knowledge about sexually transmitted diseases in rural and periurban communities of the Asaro Valley of Eastern Highlands Province: The health education component of an STD study. Papua New Guin. Med. J. 1996, 39, 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Camara, H.; Nosi, S.; Munnull, G.; Badman, S.G.; Bolgna, J.; Kuk, J.; Mola, G.; Guy, R.; Vallely, A.J.; Kelly-Hanku, A. Women’s acceptability of a self-collect HPV same-day screen-and-treat program in a high burden setting in the Pacific. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tynan, A.; Vallely, A.; Kelly, A.; Law, G.; Millan, J.; Siba, P.; Kaldor, J.; Hill, P.S. Vasectomy as a proxy: Extrapolating health system lessons to male circumcision as an HIV prevention strategy in Papua New Guinea. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropa, B.; Flint, J.; O’Reilly, M.; Pavlin, B.I.; Dagina, R.; Peni, B.; Bauri, M.; Pukienei, A.; Merritt, T.; Terrell-Perica, S.; et al. Lessons from the first 6 years of an intervention-based field epidemiology training programme in Papua New Guinea, 2013–2018. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hsieh, M.Y.; Chen, A.W.G.; Kao, N.H.L.; Chen, M.K. The effectiveness of school educating program for betel quid chewing: A pilot study in Papua New Guinea. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018, 81, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowse, J.; Cash, S.; Vilsoi, J.; Rose’Meyer, R.B. An evaluation of a culturally tailored presentation for diabetes education of indigenous communities of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2013, 33, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoyibi, T.; Keam, T.; Kuma, A.; Haihuie, T.; Hapolo, M.; Islam, S.; Akumu, B.; Chani, K.; Morris, L.; Taune, M. A pilot model of patient education and counselling for drug-resistant tuberculosis in Daru, Papua New Guinea. Public Health Action 2019, 9, S80–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maha, A.; Majumdar, S.S.; Main, S.; Phillip, W.; Witari, K.; Schulz, J.; Cros, P.d. The effects of decentralisation of tuberculosis services in the East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea. Public Health Action 2019, 9, S43–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, L.; Hiasihri, S.; Chan, G.; Honjepari, A.; Tugo, O.; Taune, M.; Aia, P.; Dakulala, P.; Majumdar, S.S. The emergency response to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Daru, Western Province, Papua New Guinea, 2014–2017. Public Health Action 2019, 9, S4–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly-Hanku, A.; Thomas, V. Communicating for Health, Hope and Change: An Assessment of Information, Education and Communication Materials Produced by the Papua New Guinean Catholic HIV and AIDS Service Inc. (CHASI); Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research and University of Goroka: Goroka, Papua New Guinea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V.; Iedema, R.; Britton, K.; Eggins, J.; Kualawi, M.; Mel, M.; Papoutsaki, E. Komuniti Tok Piksa: Integrating Papua New Guinean Highland Narratives into Visual HIV Prevention and Education Material; Centre for Health Communication, University of Technology: Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V.; Eby, M. Media and Public Health Communication at the Grassroots: Village Cinemas and HIV Education in Papua New Guinea. In Health Communication in the Changing Media Landscape: Perspectives from Developing Countries; Global Transformations in Media and Communication Research; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Ford, C.L.; Iwelunmor, J.I. Why culture matters in health interventions: Lessons from HIV/AIDS stigma and NCDs. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly-Hanku, A.; Newland, J.; Aggleton, P.; Ase, S.; Aeno, H.; Fiya, V.; Vallely, L.M.; Toliman, P.J.; Mola, G.D.; Kaldor, J.M.; et al. HPV vaccination in Papua New Guinea to prevent cervical cancer in women: Gender, sexual morality, outsiders and the de-feminization of the HPV vaccine. Papillomavirus Res. 2019, 8, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, C.; Watson, A.H.A.; Lokinap, D.; Currie, T. Papua New Guinea’s Primary Health Care System: Views from the Front Line; ANU: Canberra, Australia; UNPNG: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pus, A.; Moriyama, M.; Uno, M.; Rahman, M. Identifying Factors of Obesity in Papua New Guinea: A Descriptive Study. Health 2016, 8, 1616–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenga-Ikihele, A.; McCool, J.; Dobson, R.; Fa’alau, F.; Whittaker, R. The characteristics of behaviour change interventions used among Pacific people: A systematic search and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, J.D.; Mahesh, P.; Kwa, V.; Reeve, M.; Chowdhury, H.R.; Jilini, G.; Jagilly, R.; Kamoriki, B.; Ruskin, R.; Dakulala, P.; et al. Diversity of epidemiological transition in the Pacific: Findings from the application of verbal autopsy in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 11, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessaram, T.; McKenzie, J.; Girin, N.; Roth, A.; Vivili, P.; Williams, G.; Hoy, D. Noncommunicable diseases and risk factors in adult populations of several Pacific Islands: Results from the WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqa, G.; Moodie, M.; Schultz, J.; Swinburn, B. Process evaluation of a community-based intervention program: Healthy Youth Healthy Communities, an adolescent obesity prevention project in Fiji. Glob. Health Promot. 2013, 20, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, P.; Waqa, G.; Vanualailai, N.; Schultz, J.T.; Roberts, G.; Moodie, M.; Mavoa, H.; Malakellis, M.; McCabe, M.P.; Swinburn, B.A. Reducing unhealthy weight gain in Fijian adolescents: Results of the Healthy Youth Healthy Communities study. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12 (Suppl. S2), 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palu, E.; MacMillan, D.F.; McBride, D.K.A.; Thomson, D.R.; Zarora, R.; Simmons, D. Effects of lifestyle interventions on weight amongst Pasifika communities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 25, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowiecki, D.M.; Mauch, C.E.; Middleton, G.; Bradley, A.E.; Matwiejczyk, L.K.; Golley, R.K. Digital Platforms as Effective Health Promotion Tools: An Evidence Check Review; Sax Institute for Cancer Council: Sydney, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Muñoz, L.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, L.; Porras-Segovia, A.; Courtet, P.; Baca-García, E. Mobile applications for the management of chronic physical conditions: A systematic review. Intern. Med. J. 2022, 52, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Wu, X.; Mao, J.; Wang, X.; Nie, M. T2DM Self-Management via Smartphone Applications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-A.; Choi, M.; Lee, S.A.; Jiang, N. Effective behavioral intervention strategies using mobile health applications for chronic disease management: A systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeppe, S.; Alley, S.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Bray, N.A.; Williams, S.L.; Duncan, M.J.; Vandelanotte, C. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, C.; Betancourt, J.; Ortiz, S.; Valdes Luna, S.M.; Bamrah, I.K.; Segovia, N. Barriers to the Use of Mobile Health in Improving Health Outcomes in Developing Countries: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.M.; Alley, S.; Schoeppe, S.; Vandelanotte, C. The effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Olmen, J.; Erwin, E.; García-Ulloa, A.C.; Meessen, B.; Miranda, J.J.; Bobrow, K.; Iwelunmore, J.; Nwaozuru, U.; Obiezu Umeh, C.; Smith, C.; et al. Implementation barriers for mHealth for non-communicable diseases management in low and middle income countries: A scoping review and field-based views from implementers. Wellcome Open Res. 2020, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Vaccines—Papua New Guinea. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/png/topics/vaccines (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Australian Aid. Available online: https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/australian-aid-brochure.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Reaching Every Child—Papua New Guinea. Available online: https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/red-strategy-png-report.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Robinson, L.J.; Laman, M.; Makita, L.; Lek, D.; Dori, A.; Farquhar, R.; Vantaux, A.; Witkowski, B.; Karl, S.; Mueller, I. Asia-Pacific International Center of Excellence in Malaria Research: Maximizing Impact on Malaria Control Policy and Public Health in Cambodia and Papua New Guinea. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 107, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viney, K.; Lowbridge, C.; Morishita, F.; Rahevar, K.; Oh, K.H.; Islam, T.; Marais, B.J. Evaluation of the 2016–2020 regional tuberculosis response framework, WHO Western Pacific region. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 330–341A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Win Tin, S.T.; Kubuabola, I.; Ravuvu, A.; Snowdon, W.; Durand, A.M.; Vivili, P.; Passmore, E. Baseline status of policy and legislation actions to address non communicable diseases crisis in the Pacific. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apeng, D.; Schuele, E. Implementation of the PNG national nutrition policy’s strategic action plan (2018–2022). Contemp. PNG Stud. 2021, 35, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea National Nutrition Policy 2016–2026. Available online: https://www.health.gov.pg/pdf/PM-SNNP_2018.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mila-Schaaf, K. Pacific health research guidelines: The cartography of an ethical relationship. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2009, 60, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Chen, J.; Peters, H.; Lamond, A.; Rangan, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Porykali, S.; Oge, R.; Nogua, H.; Porykali, B. What Do We Know about the Diets of Pacific Islander Adults in Papua New Guinea? A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, R.T. Narratives and narrators: Stories as routes to indigenous knowledge in Papua New Guinea. IUP J. Commonw. Lit. 2009, 1, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Office. Demographics and Health Survey. Available online: https://www.nso.gov.pg/census-surveys/demographic-and-health-survey/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- The Public Health Division of the Pacific Community. Pacific Guidelines for Healthy Living. Available online: https://spccfpstore1.blob.core.windows.net/digitallibrary-docs/files/b9/b99bef425ec9d5e0b3713923ff0dee3c.pdf?sv=2015-12-11&sr=b&sig=zZwPoRJHnTx5Xvqrt2For%2FtA%2B6f%2B9MuZ0y2EKHA2ZpA%3D&se=2024-06-26T05%3A05%3A55Z&sp=r&rscc=public%2C%20max-age%3D864000%2C%20max-stale%3D86400&rsct=application%2Fpdf&rscd=inline%3B%20filename%3D%22Web_2___Version_2_Live_Healthy_Stay_Healthy_poster.pdf%22 (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- The Public Health Division of the Pacific Community. Pacific Guidelines for Healthy Living: A Handbook for Health Professionals and Educators. Available online: https://www.spc.int/sites/default/files/resources/2018-05/Pacific%20guidelines%20for%20healthy%20living.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Webster, J.; Waqa, G.; Thow, A.-M.; Allender, S.; Lung, T.; Woodward, M.; Rogers, K.; Tukana, I.; Kama, A.; Wilson, D.; et al. Scaling-up food policies in the Pacific Islands: Protocol for policy engagement and mixed methods evaluation of intervention implementation. Nutr. J. 2022, 21, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EQUATOR Network. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency of Health Research: Reporting Guidelines. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).