The Psychosocial Aspects of Vegetarian Diets: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Motivations, Risks, and Limitations in Daily Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conducting the Survey

2.2. Questionnaire Survey

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Declared Reasons and Daily Restrictions for a Vegetarian Diet

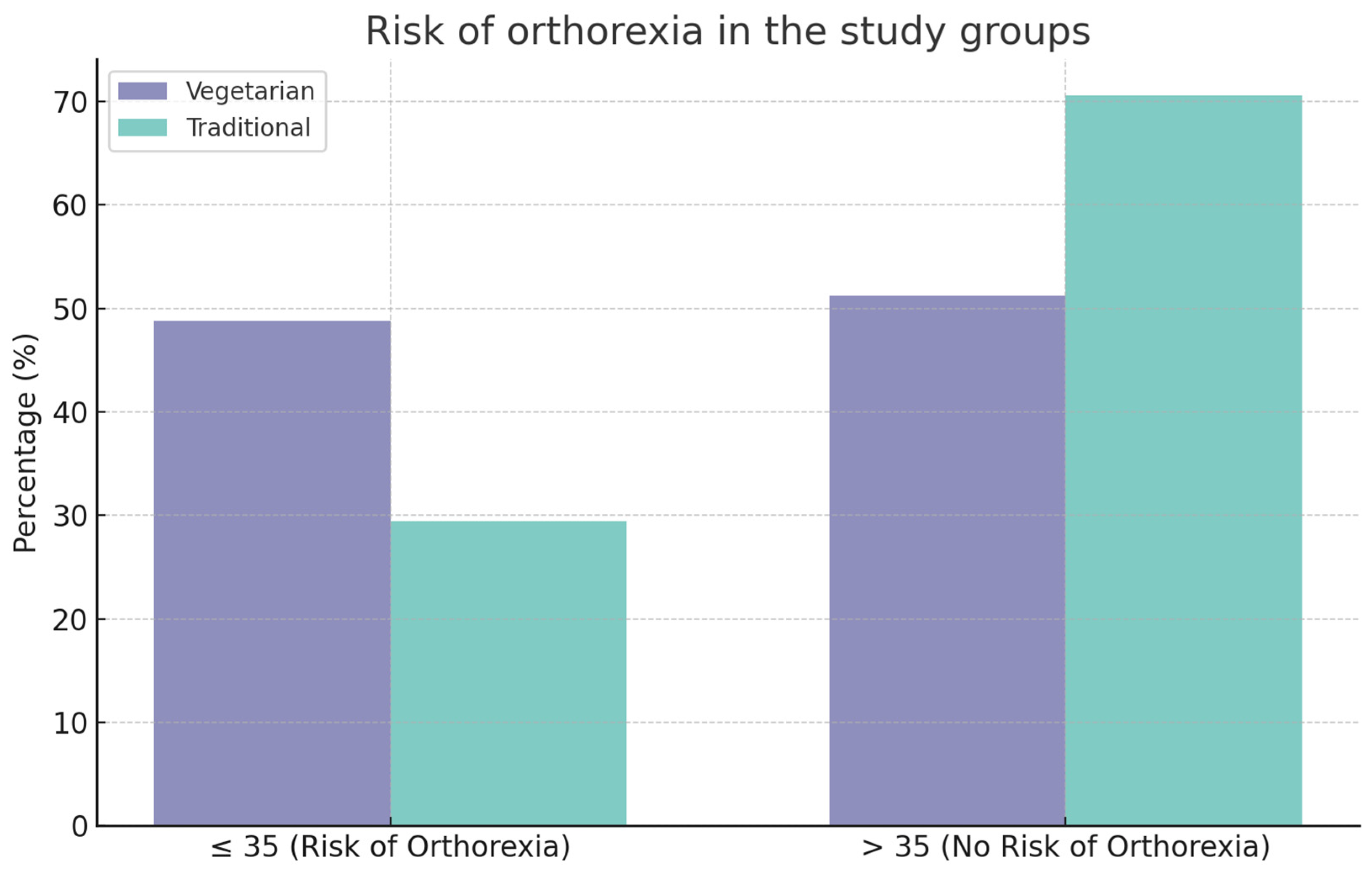

3.3. An Analysis of the Results Obtained Using the ORTO-15 Questionnaire

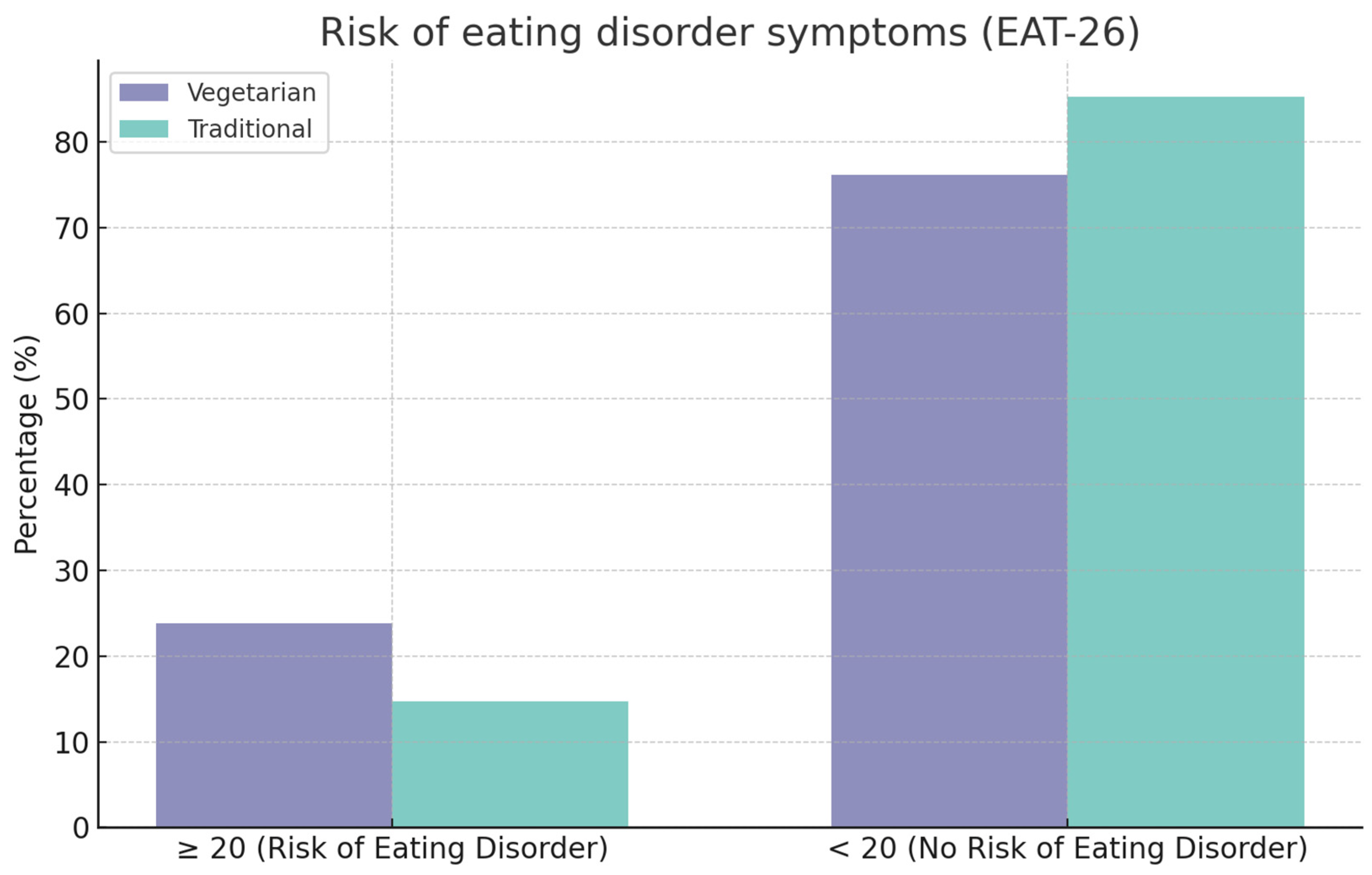

3.4. An Analysis of the Results Obtained Using the EAT-26 Questionnaire

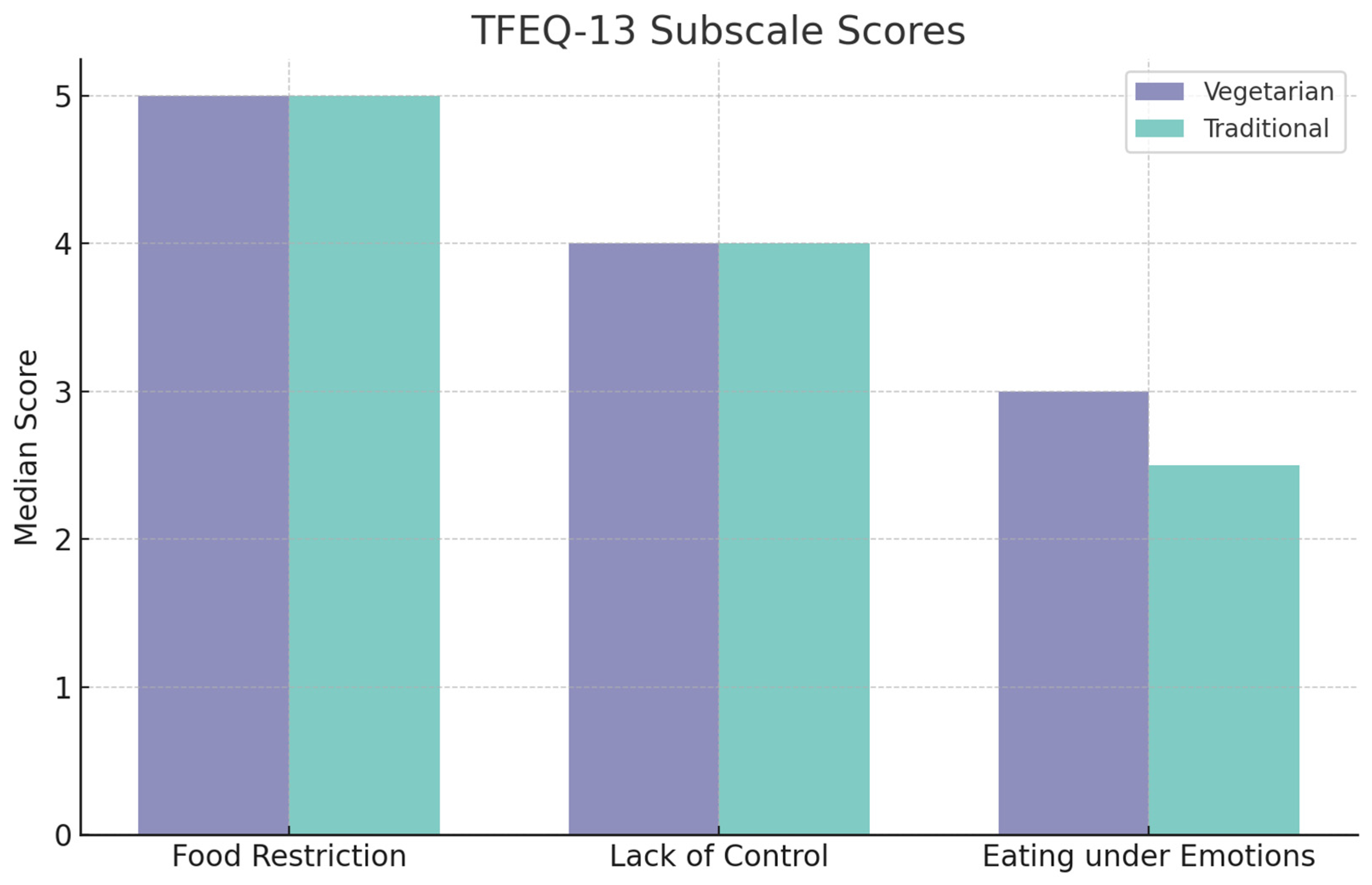

3.5. An Analysis of the Results Obtained Using the TFEQ-13 Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. The Strengths and Limitations of This Study

6. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gadzała, K.; Lesiów, T. Wybrane aktualne trendy żywieniowe. Praca przeglądowa. Nauk. Inżynierskie Technologie. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2019, 2, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brytek-Matera, A. Interaction between Vegetarian versus Omnivorous Diet and Unhealthy Eating Patterns (Orthorexia Nervosa, Cognitive Restraint) and Body Mass Index in Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cader, P.; Lesiów, T. Weganizm i wegetarianizm jako diety we współczesnym społeczeństwie konsumpcyjnym. Nauk. Inżynierskie Technol. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2021, 37, 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jedlecka, W. Wegetarianizm we współczesnych religiach światowych. Zarys problemu. Filoz. Publiczna Eduk. Demokr. 2016, 5, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Bleidorn, W.; Schwaba, T.; Chen, S. Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhont, K.; Ioannidou, M. Similarities and differences between vegetarians and vegans in motives for meat-free and plant-based diets. Appetite 2024, 195, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Rosenfeld, D.; Chen, S.; Bleidorn, W. An investigation of plantbased dietary motives among vegetarians and omnivores. Collabra Psychol. 2021, 7, 19010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maćków, M.; Zawiślak, I.; Wanio, K. Ocena wiedzy i postawa polskich studentów wobec weganizmu i wegetarianizmu. In Medycyna i Zdrowie We Współczesnym Świecie; Goluch, Z., Ed.; ArchaeGraph Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Łódź, Poland, 2022; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Goluch-Koniuszy, Z.; Zielińska, B. Ocena zachowań żywieniowych wegan będących w okresie prokreacji. Nowocz. Trendy Żywieniu Prod. Żywności 2013, 2, 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Śliwińska, A.; Olszówka, M.; Pieszko, M. Ocena wiedzy na temat diet wegetariańskich wśród populacji trójmiejskiej. Zesz. Nauk. Akad. Morskiej Gdyni 2014, 86, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, D.L. The psychology of vegetarianism: Recent advances and future directions. Appetite 2018, 131, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L. Why some choose the vegetarian option: Are all ethical motivations the same? Motiv. Emot. 2019, 43, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, A.E.; Zickgraf, H.F. Orthorexia nervosa and eating disorder behaviors: A systematic review of the literature. Appetite 2022, 177, 106134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, A.; Shrivastava, T. The Ethics of Veganism. Cureus 2024, 16, e56214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidou, M.; Lesk, V.; Stewart-Knox, B.; Francis, K.B. Moral emotions and justifying beliefs about meat, fish, dairy and egg consumption: A comparative study of dietary groups. Appetite 2023, 186, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowal, E. “To, że ileś tam osób powiedziało, że nie może się wegetarianką nazywać, to nie znaczy, że rzeczywiście nie może”—Tendencje w konstruowaniu i negocjowaniu tożsamości przez wegetarian i wegan. In Kuchnia i Stół w Komunikacji Społecznej. Tekst, Dyskurs, Kultura; Żarski, W., Ed.; Wrocławskie Wydawnictwo Oświatowe: Wrocław, Poland, 2017; pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sitko, B. Wegetarianizm ekologiczny jako ratunek dla klimatu i środowiska. Wybrane problemy i kierunki proekologicznych działań. Facta Ficta J. Theory Narrat. Media 2021, 8, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Saja, K. Minimalizacja cierpienia zwierząt a wegetarianizm. Anal. Egzystencja Czas. Filoz. 2013, 22, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Schmidt, U.J. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: A review of influence factors. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.J.; Ricotta, D.N.; Freed, J.; Smith, C.C.; Huang, G.C. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a Framework for Resident Wellness. Teach. Learn. Med. 2019, 31, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glinkowska, B. Potrzeba przynależności—Elementarna czy rzędu wyższego? In Zachowania Organizacyjne. Relacje Społeczne w Przestrzeni Zmian; Januszkiewicz, K., Czajkowska, M., Kołodziejczak, M., Zalewska-Turzyńska, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2015; pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Orszulak-Dudkowska, K. Dieta roślinna i zaangażowanie społeczne w praktykach dyskursywnych społeczności internetowych. Zesz. Wiej. 2020, 26, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węcławiak, A.A. Lewacka sałata–Ekonomiczne aspekty weganizmu. ER(R)GO. Teor.-Lit.-Kult. 2019, 38, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, K.; Okręglicka, K.; Czajkowska, K.; Nitsch-Osuch, A. Dieta wegańska w prewencji i leczeniu wybranych chorób cywilizacyjnych. Forum Med. Rodz. 2021, 15, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Masedunskas, A.; Willett, W.C.; Fontana, L. Vegetarian and vegan diets: Benefits and drawbacks. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3423–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics, 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://icd.who.int/ (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Cena, H.; Barthels, F.; Cuzzolaro, M.; Bratman, S.; Brytek-Matera, A.; Dunn, T.; Varga, M.; Missbach, B.; Donini, L.M. Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: A narrative review of the literature. Eat. Weight Disord. 2019, 24, 209–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, T.M.; Bratman, S. On orthorexia nervosa: A review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat. Behav. 2016, 21, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittfeld, A.; Koszowska, A.; Fizia, K.; Ziora, K. Ortoreksja—Nowe zaburzenie odżywiania. Ann. Acad. Medicae Silesiensis 2013, 67, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Gwioździk, W.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Całyniuk, B.; Helisz, P.; Grajek, M.; Głogowska-Ligus, J. Traditional, Vegetarian, or Low FODMAP Diets and Their Relation to Symptoms of Eating Disorders: A Cross-Sectional Study among Young Women in Poland. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontillo, M.; Zanna, V.; Demaria, F.; Averna, R.; Di Vincenzo, C.; De Biase, M.; Di Luzio, M.; Foti, B.; Tata, M.C.; Vicari, S. Orthorexia Nervosa, Eating Disorders, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Selective Review of the Last Seven Years. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koven, N.S.; Abry, A.W. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: Emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brytek-Matera, A.; Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Jurzak, H.; Kornacka, M.; Kołodziejczyk, N. Strict health-oriented eating patterns (orthorexic eating behaviours) and their connection with a vegetarian and vegan diet. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2019, 24, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gortat, M. Ortoreksja Jako Zagrożenie dla Zdrowia i Psychospołecznego Funkcjonowania Człowieka; Uniwersytet Medyczny w Lublinie: Lublin, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Narodowe Centrum Edukacji Żywieniowej—Prof. Dr Hab. n. Med. Longina Kłosiewicz-Latoszek. Jak Rozpoznać Nadwagę? Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/zdrowe-odchudzanie/jak-rozpoznac-nadwage/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Brytek-Matera, A.; Krupa, M.; Poggiogalle, E.; Donini, L.M. Adaptation of the ORTHO-15 test to Polish women and men. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2014, 19, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łucka, I.; Janikowska-Hołoweńko, D.; Domarecki, P.; Plenikowska-Ślusarz, T.; Domarecka, M. Orthorexia nervosa—A separate clinical entity, a part of eating disorder spectrum or another manifestation of obsessive-compulsive disorder? Psychiatr. Pol. 2019, 53, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzielska, A.; Mazur, J.; Małkowska-Szkutnik, A.; Kołoło, H. Adaptacja polskiej wersji kwestionariusza Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ-13) wśród młodzieży szkolnej w badaniach populacyjnych. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2009, 90, 362–369. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, C.T.; Temple, N.; Woodside, J.V. Vegetarian diets, low-meat diets and health: A review. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 2287–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CBOS. Zachowania Żywieniowe Polaków. NR 115/2014, Warszawa. 2014. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2014/K_115_14.PDF (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Kwaśniewska, M.; Pikala, M.; Grygorczuk, O.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Stepaniak, U.; Pająk, A.; Kozakiewicz, K.; Nadrowski, P.; Zdrojewski, T.; Puch-Walczak, A.; et al. Dietary Antioxidants, Quality of Nutrition and Cardiovascular Characteristics among Omnivores, Flexitarians and Vegetarians in Poland-The Results of Multicenter National Representative Survey WOBASZ. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüpbach, R.; Wegmuller, R.; Berguerand, C.; Bui, M.; Herteraeberli, I. Micronutrient status and intake in omnivores, vegetarians and vegans in Switzerland. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elorinne, A.-L.; Alfthan, G.; Erlund, I.; Kivimäki, H.; Paju, A.; Salminen, I.; Turpeinen, U.; Voutilainen, S.; Laakso, J. Food and Nutrient Intake and Nutritional Status of Finnish Vegans and Non-Vegetarians. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allès, B.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Touvier, M.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Nutritional Characteristics between Self-Reported Vegetarians, Vegans, and Meat-Eaters from the NutriNet-Santé Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deliens, T.; Mullie, P.; Clarys, P. Plant-based dietary patterns in Flemish adults: A 10-year trend analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 61, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, H.; Larpin, C.; De Mestral, C.; Guessous, I.; Reny, J.-L.; Stringhini, S. Vegetarian, pescatarian and flexitarian diets: Sociodemographic determinants and association with cardiovascular risk factors in a Swiss urban population. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.H.T.; Pan, W.H.; Lin, M.N.; Lin, C.L. Vegetarian diet, change in dietary patterns, and diabetes risk: A prospective study. Nutr. Diabetes 2018, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahleova, H.; Fleeman, R.; Hlozkova, A.; Holubkov, R.; Barnard, N.D. A plant-based diet in overweight individuals in a 16-week randomized clinical trial: Metabolic benefits of plant protein. Nutr. Diabetes 2018, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Młoda-Brylewska, K.; Młoda, O. Determinanty wyboru diety roślinnej przez konsumentów. In Nauka, Badania i Doniesienia Naukowe; Wysoczański, T., Ed.; Idea Knowledge Future: Świebodzin, Poland, 2019; pp. 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, M.W.; Korek, E. Przegląd niespecyficznych zaburzeń odżywiania. Neuropsychiatr. Neuropsychol. 2020, 15, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brytek-Matera, A. Vegetarian diet and orthorexia nervosa: A review of the literature. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthels, F.; Meyer, F.; Pietrowsky, R. Orthorexic and restrained eating behaviour in vegans, vegetarians, and individuals on a diet. Eat. Weight Disord. 2018, 23, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, C.P.; Kulkarni, J.; Sharp, G. Disordered eating and the meat-avoidance spectrum: A systematic review and clinical implications. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 2347–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, R.; McGowan, A.; Smith, S.; Rawstorne, P. Vegan and vegetarian males and females have higher orthorexic traits than omnivores, and are motivated in their food choice by factors including ethics and weight control. Nutr. Health 2023, 4, 02601060231187924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’osso, L.; Carpita, B.; Muti, D.; Cremone, I.M.; Massimetti, G.; Diadema, E.; Gesi, C.; Carmassi, C. Prevalence and characteristics of orthorexia nervosa in a sample of university students in Italy. Eat. Weight Disord. 2018, 23, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, S.; Coffino, J.A.; Hormes, J.M. What does the ORTO-15 measure? Assessing the construct validity of a common orthorexia nervosa questionnaire in a meat avoiding sample. Appetite 2019, 135, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, C.P.; Kulkarni, J.; Sharp, G. The 26-Item Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26): Psychometric Properties and Factor Structure in Vegetarians and Vegans. Nutrients 2023, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergentanis, T.N.; Chelmi, M.-E.; Liampas, A.; Yfanti, C.-M.; Panagouli, E.; Vlachopapadopoulou, E.; Michalacos, S.; Bacopoulou, F.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsitsika, A. Vegetarian Diets and Eating Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Children 2021, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Manzaneque-Cañadillas, M.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Fernández-Muñoz, J.J.; Prado-Laguna, M.D.C.; Brytek-Matera, A. Pathological Preoccupation with Healthy Eating (Orthorexia Nervosa) in a Spanish Sample with Vegetarian, Vegan, and Non-Vegetarian Dietary Patterns. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.J.; Dripps, W.R.; Blomquist, K.K. Organivore or organorexic? Examining the relationship between alternative food network engagement, disordered eating, and special diets. Appetite 2016, 1, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missbach, B.; Hinterbuchinger, B.; Dreiseitl, V.; Zellhofer, S.; Kurz, C.; König, J. When eating right, is measured wrong! A validation and critical examination of the ORTO-15 questionnaire in German. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, J.H.; Ruiz, P.A.; Valdespino, B.R.; Visioli, F. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among ashtanga yoga practitioners: A pilot study. Eat. Weight Disord. 2014, 19, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck-Sikorski, C.; Jung, F.; Schlosser, K.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Is orthorexic behavior common in the general public? A large representative study in Germany. Eat. Weight Disord. 2018, 24, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, S.; Coffino, J.A.; Hormes, J.M. Eating and health behaviors in vegans compared to omnivores: Dispelling common myths. Appetite 2017, 118, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Perry, C.L.; Wall, M.M.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Adolescent and young adult vegetarianism: Better dietary intake and weight outcomes but increased risk of disordered eating behaviors. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickgraf, H.F.; Barrada, J.R. Orthorexia nervosa vs. healthy orthorexia: Relationships with disordered eating, eating behavior, and healthy lifestyle choices. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 27, 1313–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baş, M.; Karabudak, E.; Kiziltan, G. Vegetarianism and eating disorders: Association between eating attitudes and other psychological factors among Turkish adolescents. Appetite 2005, 44, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metric Data | People Following a Vegetarian Diet, n = 84 (100%) | People Following a Traditional Diet, n = 102 (100%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Woman | 82 | 97.6 | 93 | 91.2 |

| Male | 2 | 2.4 | 9 | 8.8 | |

| Age | 18–26 years | 61 | 72.6 | 75 | 73.5 |

| 27–40 years | 16 | 19.0 | 17 | 16.3 | |

| 41 years and over | 7 | 8.3 | 10 | 9.8 | |

| Professional activity | Pupil/student | 29 | 34.5 | 39 | 38.2 |

| Working pupil/student | 31 | 36.9 | 40 | 39.2 | |

| Working person | 21 | 25.0 | 21 | 20.6 | |

| Unemployed person | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.0 | |

| Other | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.0 | |

| Education | Primary school | 3 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Gymnasium | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.9 | |

| Vocational school | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.0 | |

| High school | 41 | 48.8 | 42 | 41.2 | |

| University | 39 | 46.4 | 56 | 54.9 | |

| BMI | People Following a Vegetarian Diet, n = 84 | People Following a Traditional Diet, n = 102 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Underweight | 13 | 15.5 | 16 | 15.7 | p = 0.47 |

| Normal | 58 | 69.0 | 61 | 59.8 | |

| Overweight | 9 | 10.7 | 18 | 17.6 | |

| Obesity | 4 | 4.8 | 7 | 6.9 | |

| Reasons for Limiting or Completely Giving Up Eating Meat and/or Animal Products (Multiple Choice Question) | People Following a Vegetarian Diet, n = 84 | People Following a Traditional Diet, n = 102 | p-Value 0.05 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Ethical and/or environmental considerations | 73 | 86.9 | 21 | 20.6 | <0.0001 |

| Reigning ‘fashion’ and dietary trends | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.9 | 0.3174 |

| Influence of environment (relatives/family) | 5 | 6.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 0.3000 |

| The belief that vegetarian diets have a positive impact on health | 27 | 32.1 | 12 | 11.8 | 0.0007 |

| Willingness to ‘take care’ of your health | 36 | 42.9 | 30 | 29.4 | 0.0565 |

| Health status | 7 | 8.3 | 10 | 9.8 | 0.7283 |

| Aversion to the taste of meat and/or animal products (milk and milk products. eggs) | 54 | 64.3 | 32 | 31.4 | <0.0001 |

| I do not follow any vegetarian diet and I do not restrict my intake of animal products | 0 | 0.0 | 44 | 43.1 | <0.0001 |

| People Following a Vegetarian Diet, n = 84 | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Perception of restriction in restaurants/cafes due to vegetarian diet | ||

| Not ever | 11 | 13.09 |

| Only sometimes | 52 | 61.90 |

| So often | 17 | 20.23 |

| I only go to restaurants/cafes with vegetarian/vegan menus | 4 | 4.76 |

| Avoiding going out to restaurants/cafes due to feeling excluded because of their vegetarian diet | ||

| Not | 45 | 53.57 |

| Sometimes | 23 | 27.38 |

| Yes | 3 | 3.57 |

| I don’t feel restricted | 13 | 15.47 |

| Perception of exclusion among friends and/or family due to vegetarian diet | ||

| Not | 40 | 47.61 |

| Only sometimes | 38 | 45.23 |

| Yes | 6 | 7.14 |

| Avoiding gatherings with friends and/or family due to feelings of exclusion because of their vegetarian diet | ||

| Not | 65 | 77.38 |

| Sometimes | 3 | 3.57 |

| Yes | 1 | 1.19 |

| I don’t feel restricted | 15 | 17.85 |

| Sense of exclusion during trips, e.g., holidays, due to vegetarian diet | ||

| Not | 37 | 44.04 |

| Only sometimes | 37 | 44.04 |

| yes | 10 | 11.90 |

| Feelings of restriction when grocery shopping due to vegetarian diet | ||

| Not | 49 | 58.33 |

| Only sometimes | 29 | 34.52 |

| yes | 6 | 7.14 |

| Variable | Average | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORTO-15 in the group of people following a vegetarian diet, n = 84 | 35.76 | 3.50 | 28.00 | 46.00 | (34.99, 36.52) | p = 0.005 | |

| ORTO-15 in the group of people following a traditional diet, n = 102 | 37.24 | 3.54 | 25.00 | 46.00 | (36.55, 37.93) | ||

| Risk of Orthorexia | People Following a Vegetarian Diet, n = 84 | People Following a Traditional Diet, n = 102 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| There is a risk of orthorexia | 41 | 48.8 | 30 | 29.4 | p = 0.00673 |

| The risk of orthorexia is lower | 43 | 51.2 | 72 | 70.6 | |

| Variable | Median | Quartile Range | Minimum | Maximum | CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAT-26 in the vegetarian diet group, n = 84 | 9.50 | 12.00 | 1.00 | 67.00 | (7.57, 11.43) | p = 0.21762 |

| EAT-26 in the group of people following a traditional diet, n = 102 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 1.00 | 65.00 | (6.83, 9.17) |

| Questionnaire EAT-26 | People Following a Vegetarian Diet, n = 84 | People Following a Traditional Diet, n = 102 | CI | p-Value 0.05 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Quartile Range | Median | Quartile Range | |||

| Subscale 1: weight loss | 5.00 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 8.00 | V (3.39, 6.61) | 0.31983 |

| O (3.83, 6.17) | ||||||

| Subscale 2: bulimia and eating control | 3.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | V (2.68, 3.32) | 0.04428 |

| O No | ||||||

| V (−0.48, 0.48) | ||||||

| Subscale 3: oral control | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | O (−0.44, 0.44) | 0.74261 |

| Risk of Developing Eating Disorder Symptoms | People Following a Vegetarian Diet, n = 84 | People Following a Traditional Diet, n = 102 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| There is a risk of eating disorder symptoms | 20 | 23.8 | 15 | 14.7 | p = 0.11391 |

| The risk of developing eating disorder symptoms is lower | 64 | 76.2 | 87 | 85.3 | |

| TFEQ-13 Questionnaire | People Following a Vegetarian Diet, n = 84 | People Following a Traditional Diet, n = 102 | CI | p-Value 0.05 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Quartile Range | Median | Quartile Range | |||

| Subscale 1: food restriction | 5.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | V (3.87, 6.13) | 0.77279 |

| O (4.27, 5.73) | ||||||

| Subscale 2: lack of control in overeating | 4.00 | 4.50 | 4.00 | 5.00 | V (3.28, 4.72) | 0.91935 |

| O (3.27, 4.73) | ||||||

| Subscale 3: eating under the influence of emotions | 3.00 | 5.00 | 2.50 | 3.00 | V (2.20, 3.80) | 0.16612 |

| O (2.06, 2.94) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Białek-Dratwa, A.; Stoń, W.; Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W.; Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Kowalski, O. The Psychosocial Aspects of Vegetarian Diets: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Motivations, Risks, and Limitations in Daily Life. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152504

Białek-Dratwa A, Stoń W, Staśkiewicz-Bartecka W, Grajek M, Krupa-Kotara K, Kowalski O. The Psychosocial Aspects of Vegetarian Diets: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Motivations, Risks, and Limitations in Daily Life. Nutrients. 2024; 16(15):2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152504

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiałek-Dratwa, Agnieszka, Wiktoria Stoń, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, Mateusz Grajek, Karolina Krupa-Kotara, and Oskar Kowalski. 2024. "The Psychosocial Aspects of Vegetarian Diets: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Motivations, Risks, and Limitations in Daily Life" Nutrients 16, no. 15: 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152504

APA StyleBiałek-Dratwa, A., Stoń, W., Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W., Grajek, M., Krupa-Kotara, K., & Kowalski, O. (2024). The Psychosocial Aspects of Vegetarian Diets: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Motivations, Risks, and Limitations in Daily Life. Nutrients, 16(15), 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152504