Cooking Well with Diabetes: A Healthy Cooking School for Diabetes Prevention and Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

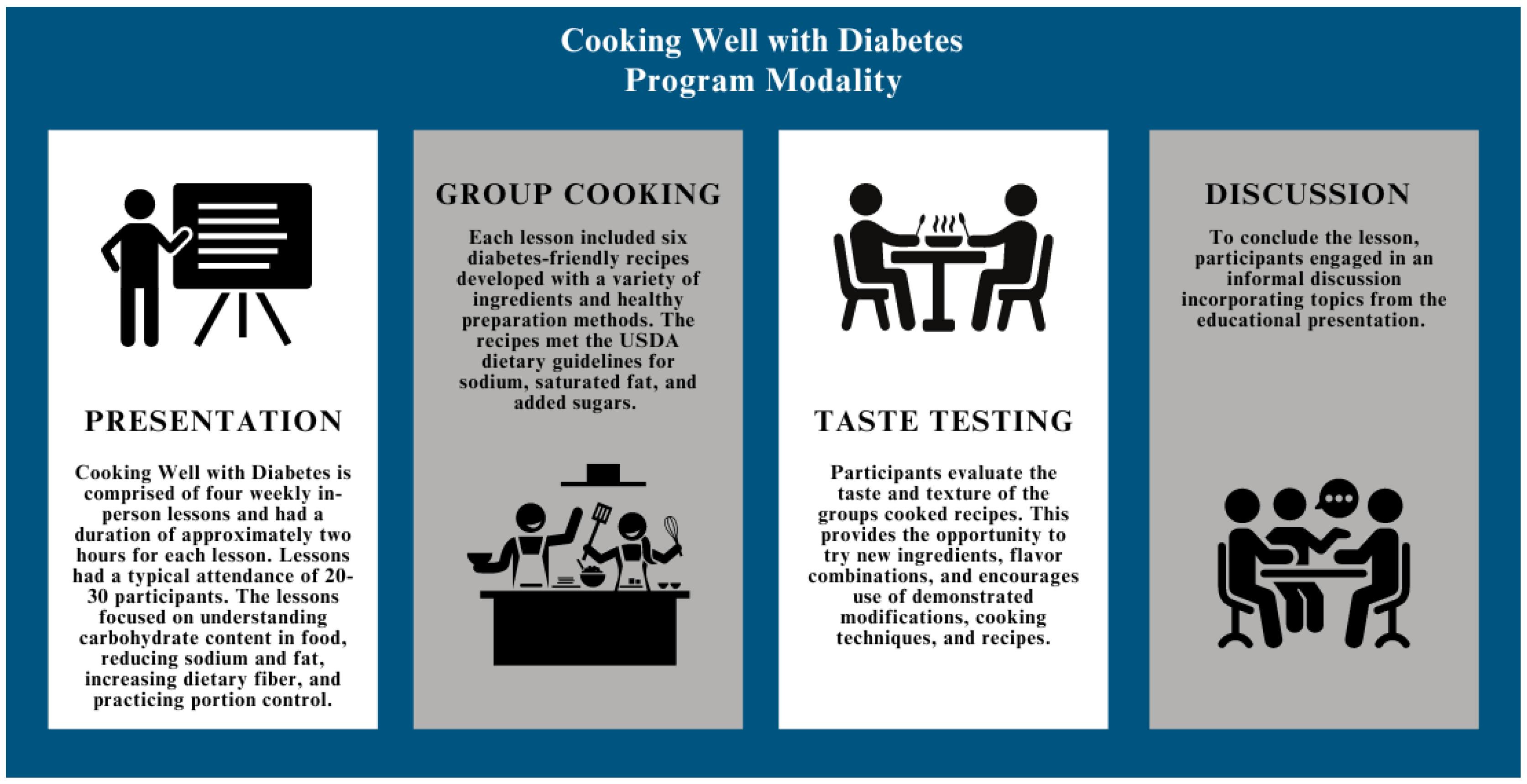

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. General Health, Physical Activity, and Nutrition

3.3. Healthy Cooking Practices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Balaji, R.; Duraisamy, R.; Kumar, M.P.S. Complications of diabetes mellitus: A review. Drug Invent. Today 2019, 12, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, A.; Handelsman, Y.; Heile, M.; Shannon, M. Burden of Illness in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2018, 24, S5–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauricio, D.; Alonso, N.; Gratacòs, M. Chronic diabetes complications: The need to move beyond classical concepts. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, K.; Maryniuk, M.; Peeples, M.; Peyrot, M.; Tomky, D.; Weaver, T.; Yarborough, P. Diabetes self-management education core outcomes measures. Diabetes Educ. 2003, 29, 768–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A.O.; Lowis, C.; Dean, M.; Hunter, S.J.; McKinley, M.C. Diet and physical activity in the self-management of type 2 diabetes: Barriers and facilitators identified by patients and health professionals. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2013, 14, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers, D.; Garth, K.; Manley, D.; Chlebowy, D. Facilitators and Barriers to Type 2 Diabetes Self-Management among Rural African American Adults. J. Health Disparities Res. Pract. 2016, 9, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Marcy, T.R.; Britton, M.L.; Harrison, D. Identification of barriers to appropriate dietary behavior in low-income patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2011, 2, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nor, N.M.; Shukri, N.M.; Yassin, N.Q.A.M.; Sidek, S.; Azahari, N. Barriers and Enablers to Make Lifestyle Changes among Type 2 Diabetes Patients: A Review. Sains Malays. 2019, 48, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Stotz, S.A.; Ricks, K.A.; Eisenstat, S.A.; Wexler, D.J.; Berkowitz, S.A. Opportunities for Interventions That Address Socioeconomic Barriers to Type 2 Diabetes Management: Patient Perspectives. Sci. Diabetes Self-Manag. Care 2021, 47, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotz, S.; Brega, A.G.; Henderson, J.N.; Lockhart, S.; Moore, K. Food Insecurity and Associated Challenges to Healthy Eating Among American Indians and Alaska Natives with Type 2 Diabetes: Multiple Stakeholder Perspectives. J. Aging Health 2021, 33, 31S–39S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Food and Agriculture. United States Department of Agriculture. Cooperative Extension History. Available online: https://www.nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa/how-we-work/extension/cooperative-extension-history (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Ha, N.T.; Phuong, N.T.; Ha, L.T.T. How dietary intake of type 2 diabetes mellitus outpatients affects their fasting blood glucose levels? AIMS Public Health 2019, 6, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Russell, W.R.; Baka, A.; Björck, I.; Delzenne, N.; Gao, D. Impact of Diet Composition on Blood Glucose Regulation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 541–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolla, A.M.; Caretto, A.; Laurenzi, A.; Scavini, M.; Piemonti, L. Low-Carb and Ketogenic Diets in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2019, 11, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, M.E.; Cavanaugh, K.L.; Wolff, K.; Davis, D.; Gregory, R.P.; Shintani, A.; Eden, S.; Wallston, K.; Elasy, T.; Rothman, R.L. The diabetes nutrition education study randomized controlled trial: A comparative effectiveness study of approaches to nutrition in diabetes self-management education. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1368–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.R.; Bellamkonda, S.; Zilbermint, M.; Wang, J.; Kalyani, R.R. Effects of the low carbohydrate, high fat diet on glycemic control and body weight in patients with type 2 diabetes: Experience from a community-based cohort. BMJ Open Diab Res. Care 2020, 8, e000980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griauzde, D.H.; Ling, G.; Wray, D.; DeJonckheere, M.; Mizokami Stout, K.; Saslow, L.R.; Fenske, J.; Serlin, D.; Stonebraker, S.; Nisha, T.; et al. Continuous Glucose Monitoring with Low-Carbohydrate Nutritional Coaching to Improve Type 2 Diabetes Control: Randomized Quality Improvement Program. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e31184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, M.J.; MacLeod, J.; Evert, A.; Brown, C.; Gradwell, E.; Handu, D.; Reppert, A.; Robinson, M. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Nutrition Practice Guideline for Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: Systematic Review of Evidence for Medical Nutrition Therapy Effectiveness and Recommendations for Integration into the Nutrition Care Process. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1659–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottalib, A.; Salsberg, V.; Mohd-Yusof, B.N.; Mohamed, W.; Carolan, P.; Pober, D.M.; Mitri, J.; Hamdy, O. Effects of nutrition therapy on HbA1c and cardiovascular disease risk factors in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin-Fowler, R.A.; Hanson, K.L.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Kolodinsky, J.; Sitaker, M.; Ammerman, A.S.; Marshall, G.A.; Belarmino, E.H.; Garner, J.A.; Wang, W. Community Supported Agriculture Plus Nutrition Education Improves Skills, Self-efficacy, and Eating Behaviors among Low-Income Caregivers but not their Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Shrodes, J.C.; Radabaugh, J.N.; Braun, A.; Kline, D.; Zhao, S.; Brock, G.; Nolan, T.S.; Garner, J.A.; Spees, C.K.; et al. Outcomes of Cooking Matters for Diabetes: A 6-week Randomized, Controlled Cooking and Diabetes Self-Management Education Intervention. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 123, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archuleta, M.; VanLeeuwen, D.; Halderson, K.; Bock, M.A.; Eastman, W.; Powell, J.; Titone, M.; Marr, C.; Wells, L. Cooking Schools Improve Nutrient Intake Patterns of People with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, C.; Kurmas, N.; Burant, C.J.; Utech, A.; Steiber, A.; Julius, M. Cooking Classes: A Diabetes Self-Management Support Intervention Enhancing Clinical Values. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantle, J.P.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Albright, A.L.; Apovian, C.M.; Clark, N.G.; Franz, M.J.; Hoogwerf, B.J.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Mayer-Davis, E.; Mooradian, A.D.; et al. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, S61–S78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vural, H.; Uzuner, A.; Unalan, P.C.; Sınav, H.O. The effect of basic carbohydrate counting on HbA1c in type 2 diabetic patients: A non-randomized controlled trial. Prim. Care Diabetes 2023, 17, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extension Foundation. National Cooperative Extension Projects. Available online: https://extension.org/tools/national-cooperative-extension-projects/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Wilson, H.K.; Castillo-Hernandez, I.M.; Evans, E.M.; Williams, E.R.; Berg, A.C. Diet Quality Outcomes of a Cooperative Extension Diabetes Prevention Program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2023, 55, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, C.J.; Sherrill, W.W.; Stancil, M.; Rennert, L.; Parisi, M.; McFall, D. Health Extension for Diabetes: Impact of a Community-Based Diabetes Self-Management Support Program on Older Adults’ Activation. Diabetes Spectr. 2023, 36, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafie, C.; Hosig, K.; Wenzel, S.G.; Borowski, S.; Jiles, K.A.; Schlenker, E. Implementation and outcomes of the balanced living with Diabetes program conducted by Cooperative extension in rural communities in Virginia. Rural. Remote Health 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S77–S110. [CrossRef]

| Food Category | Food Type | Serving Size | Carbohydrate Choices * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starch and Whole Grains | Bread | 1 slice | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Hot Dog or Hamburger Bun | ½ a bun | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | English Muffin | ½ a muffin | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Bagel (4 ounce) | ¼ a bagel | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Pancake (4 inches) | 1 pancake | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Tortilla (6 inches) | 1 tortilla | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Pasta or Rice | 1/3 a cup | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Bran | ½ cup | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Cereal, unsweetened | ¾ cup | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Cereal, Cooked | 1/3 cup | 1 |

| Starch and Whole Grains | Crackers, Saltines | 6 crackers | 1 |

| Starchy Vegetables | Corn | ½ cup | 1 |

| Starchy Vegetables | Potatoes | ½ cup | 1 |

| Starchy Vegetables | Yams | ½ cup | 1 |

| Starchy Vegetables | Sweet Potatoes | ½ cup | 1 |

| Starchy Vegetables | Winter Squash | 1 cup | 1 |

| Starchy Vegetables | Baked Beans | 1/3 cup | 1 |

| Starchy Vegetables | Beans | ½ cup | 1 |

| Starchy Vegetables | Peas | ½ cup | 1 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Cake, frosted | 2-inch square | 2 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Cake, unfrosted | 2-inch square | 1 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Angel Food Cake | 1/12 | 2 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Glazed Doughnut | 3.75 inch | 2 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Ice Cream | ½ cup | 1 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Frozen Yogurt | ½ cup | 1 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Vanilla Wafers | 5 wafers | 1 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Fruit Cobbler | ½ cup | 3 |

| Sweets and Desserts | Pie (8 inches) | 1/8 | 3 |

| Fruit and Juices | Orange/Apple Juice | ½ cup | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Apple/Banana | 1 small | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Peach | 1 medium | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Pear, large | ½ | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Blueberries/Blackberries | ¾ cup | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Raspberries | 1 cup | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Strawberries | 1.25 cup | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Grapefruit, Large | 1/2 | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Cantaloupe, medium | 1/3 melon | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Honeydew cubes | 1 cup | 1 |

| Fruit and Juices | Grape/Prune Juice | 1/3 cup | 1 |

| Milk and Yogurt | Cow or Soy milk | 1 cup | 1 |

| Milk and Yogurt | Yogurt, Plain | 1 cup | 1 |

| Milk and Yogurt | Yogurt with Fruit | ½ cup | 1 |

| Participant Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 31 (2.5) |

| 25–34 | 63 (4.0) | |

| 35–44 | 133 (8.4) | |

| 45–54 | 211 (13.4) | |

| 55–64 | 390 (24.8) | |

| ≥65 | 706 (44.9) | |

| n/a | 40 (2.5) | |

| Gender | Male | 283 (18.0) |

| Female | 1195 (75.9) | |

| n/a | 96 (6.1) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Hispanic | 706 (44.9) |

| White | 550 (34.9) | |

| African American | 227 (14.4) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 19 (1.2) | |

| Other * | 35 (2.3) | |

| n/a | 37 (2.4) | |

| Have diagnosed diabetes | Yes | 755 (48.0) |

| No | 737 (46.8) | |

| n/a | 82 (5.2) | |

| Prepare meals for someone with diabetes | Yes | 517 (32.8) |

| No | 943 (59.9) | |

| n/a | 114 (7.2) | |

| Primary food shopper for the household | Yes | 1342 (85.3) |

| No | 144 (9.1) | |

| n/a | 88 (5.6) |

| Participant Self-Reported Health Behaviors | Pre n (%) | Post n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of general health | Excellent/very good/good | 1025 (65.1) | 1158 (73.6) | <0.001 |

| Fair/poor | 549 (34.9) | 416 (26.4) | ||

| Engage in moderate/vigorous intensity physical activity in the past month | Yes | 799 (50.8) | 1040 (66.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 643 (40.9) | 414 (26.3) | ||

| Portion of dinner plate filled with fruits and vegetables | More than 1/2 | 539 (34.2) | 740 (47.0) | <0.001 |

| Less than 1/2 | 964 (61.2) | 775 (49.2) | ||

| Fruit consumption | ≥2 times a day | 548 (34.8) | 772 (49.0) | <0.001 |

| <2 times a day | 974 (61.9) | 758 (48.2) | ||

| Vegetable consumption | ≥2 times a day | 739 (47.0) | 979 (62.2) | <0.001 |

| <2 times a day | 759 (48.2) | 555 (35.3) | ||

| Regular soda consumption | Never | 752 (47.8) | 798 (50.7) | <0.001 |

| 1–6 times a week | 488 (31.0) | 463 (29.4) | ||

| ≥1 time a day | 308 (19.6) | 245 (15.6) | ||

| Sweetened beverage consumption | Never | 655 (41.6) | 739 (47.0) | <0.001 |

| 1–6 times a week | 469 (29.8) | 468 (29.7) | ||

| ≥1 time a day | 346 (22.0) | 296 (18.8) |

| Frequency of Food Consumption and Food Practices (Always/Mostly) | Pre n (%) | Post n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Add salt to food at the table | 268 (17.0) | 245 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Replace salt with herbs and spices | 526 (33.4) | 734 (46.6) | <0.001 |

| Replace shortening/lard with vegetable oil | 1076 (68.4) | 1268 (80.6) | <0.001 |

| Modify recipes to lower sugar or fat | 513 (32.6) | 684 (43.5) | <0.001 |

| Modify recipes to increase fiber | 338 (21.5) | 521 (33.1) | <0.001 |

| Use healthy cooking methods instead of frying | 869 (55.2) | 1140 (72.4) | <0.001 |

| Add extra vegetables to casseroles and soups | 581 (36.9) | 837 (53.2) | <0.001 |

| Plan meals using the MyPlate method | 245 (15.6) | 507 (32.2) | <0.001 |

| Check nutrition facts label on food packages | 544 (34.6) | 847 (53.8) | <0.001 |

| Prepare meals and snacks at home | 994 (63.2) | 1148 (72.9) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venkatesh, S.; Leal, D.O.; Valdez, A.; Butler, P.I.; Keenan, O.E.; Montemayor-Gonzalez, E. Cooking Well with Diabetes: A Healthy Cooking School for Diabetes Prevention and Management. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2543. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152543

Venkatesh S, Leal DO, Valdez A, Butler PI, Keenan OE, Montemayor-Gonzalez E. Cooking Well with Diabetes: A Healthy Cooking School for Diabetes Prevention and Management. Nutrients. 2024; 16(15):2543. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152543

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenkatesh, Sumathi, David O. Leal, Amy Valdez, Paula I. Butler, Odessa E. Keenan, and Elaine Montemayor-Gonzalez. 2024. "Cooking Well with Diabetes: A Healthy Cooking School for Diabetes Prevention and Management" Nutrients 16, no. 15: 2543. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152543