Tobacco Use, Food Insecurity, and Low BMI in India’s Older Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

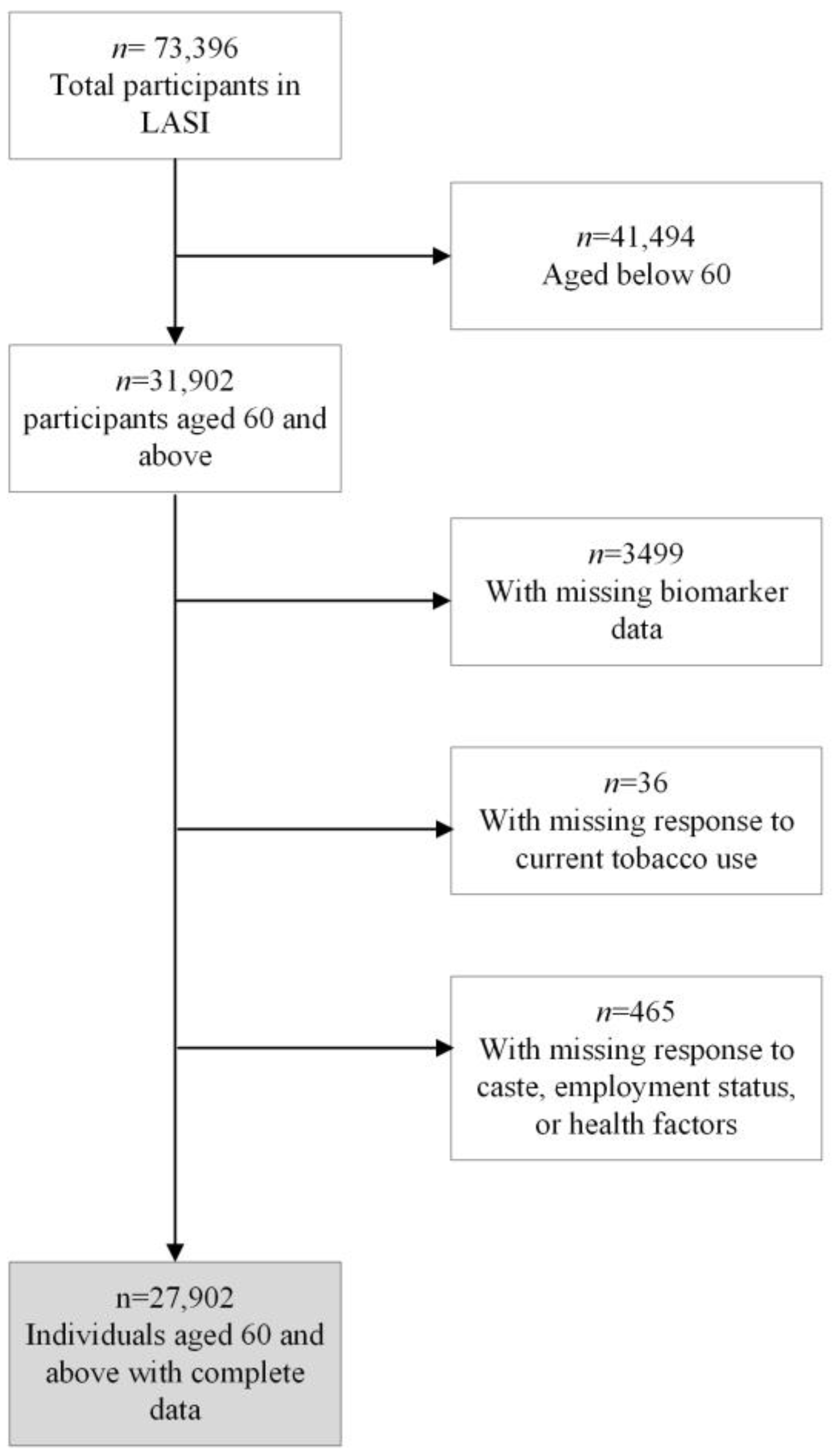

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

2.2.2. Key Explanatory Variables

- In the last 12 months, did you reduce the size of your meals or skip meals because there was not enough food at your household?

- In the last 12 months, were you hungry but did not eat because there was not enough food at your household?

- In the past 12 months, did you ever not eat for a whole day because there was not enough food at your household?

- Do you think that you have lost weight in the last 12 months because there was not enough food in your household?

2.2.3. Other Controls

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Attributes and Prevalence of Underweight by Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Multivariate Logistic Regression Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Young, M.F.; Nguyen, P.; Avula, R.; Tran, L.; Menon, P. Trends and determinants of low Body Mass Index (BMI) among 750,000 adolescents and women of reproductive age in India (P10-086-19). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz034-P10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, R.; Kulkarni, B.; Kim, R.; Subramanian, S.V. Temporal change in prevalence of BMI categories in India: Patterns across States and Union territories of India, 1999–2021. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucholz, E.M.; Krumholz, H.A.; Krumholz, H.M. Underweight, markers of cachexia, and mortality in acute myocardial infarction: A prospective cohort study of elderly medicare beneficiaries. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, L.; Braun, J.; Chiolero, A.; Bopp, M.; Rohrmann, S.; Faeh, D.; Swiss National Cohort Study Group. Mortality risk associated with underweight: A census-linked cohort of 31,578 individuals with up to 32 years of follow-up. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Prakash, A.A.; Das, P.K.; Gupta, S.; Pusdekar, Y.V.; Hibberd, P.L. Maternal anemia and underweight as determinants of pregnancy outcomes: Cohort study in eastern rural Maharashtra India. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvamani, Y.; Singh, P. Socioeconomic patterns of underweight and its association with self-rated health, cognition and quality of life among older adults in India. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, M.; Selvamani, Y.; Singh, P.; Prashad, L. The double burden of malnutrition among adults in India: Evidence from the National Family Health Survey-4 (2015–2016). Epidemiol. Health 2019, 41, e2019050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS); National Programme for Health Care of Elderly (NPHCE); MoHFW, Harvard, T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH); University of Southern California (USC). Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017–2018; India Report; International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS): Mumbai, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, B.K.; Bell, C.L.; Masaki, K.H.; Amella, E.J. Factors associated with weight loss, low BMI, and malnutrition among nursing home patients: A systematic review of the literature. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávaro-Moreira, N.C.; Krausch-Hofmann, S.; Matthys, C.; Vereecken, C.; Vanhauwaert, E.; Declercq, A.; Bekkering, G.E.; Duyck, J. Risk factors for malnutrition in older adults: A systematic review of the literature based on longitudinal data. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.L.; Dunbar, S.A.; Jaacks, L.M.; Karmally, W.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Yancy, W.S. Macronutrients, food groups, and eating patterns in the management of diabetes: A systematic review of the literature, 2010. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute for Population Sciences & United Nations Population Fund. India Ageing Report 2023, Caring for Our Elders: Institutional Responses. United Nations Population Fund. 2023. Available online: https://india.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/20230926_india_ageing_report_2023_web_version_.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Wang, Q. Underweight, overweight, and tobacco use among adolescents aged 12–15 years: Evidence from 23 low-income and middle-income countries. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2021, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pednekar, M.S.; Gupta, P.C.; Shukla, H.C.; Hebert, J.R. Association between tobacco use and body mass index in urban Indian population: Implications for public health in India. BMC Public. Health 2006, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Plurphanswat, N.; Rodu, B. The association of smoking and demographic characteristics on body mass index and obesity among adults in the US, 1999–2012. BMC Obes. 2014, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Gao, W.; Cao, W.; Lv, J.; Yu, C.; Wang, S.; Zhou, B.; Pang, Z.; Cong, L.; Dong, Z.; et al. The association of cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking with body mass index: A cross-sectional, population-based study among Chinese adult male twins. BMC Public. Health 2016, 16, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 397, 2337–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tobacco. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/india/health-topics/tobacco (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Moradi, S.; Mirzababaei, A.; Dadfarma, A.; Rezaei, S.; Mohammadi, H.; Jannat, B.; Mirzaei, K. Food insecurity and adult weight abnormality risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandapan, B.; Pradhan, I.; Pradhan, J. Food insecurity and malnutrition among Indian older adults: Findings from longitudinal ageing study in India, 2017–2018. J. Popul. Ageing 2023, 16, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Food insecurity and health outcomes among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults in India. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, J.H. Risk Factors for Food Insecurity among Older Adults in India: Study Based on LASI, 2017–2018. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S. The intersection of gender, caste and class inequalities in child nutrition in rural India. Asian Popul. Stud. 2015, 11, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosse, D. Caste and development: Contemporary perspectives on a structure of discrimination and advantage. World Dev. 2018, 110, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, Y.S.; Hong, K.H. What Is the relationship between the chewing ability and nutritional status of the elderly in Korea? Nutrients 2023, 15, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekha, P.P.; Irshad, C.V.; Azeez, E.A.; Rajan, S.I. Nutritional status of older adults in India: An exploration of the role of oral health and food insecurity factors. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineur, Y.S.; Abizaid, A.; Rao, Y.; Salas, R.; DiLeone, R.J.; Gündisch, D.; Diano, S.; De Biasi, M.; Horvath, T.L.; Gao, X.B.; et al. Nicotine decreases food intake through activation of POMC neurons. Science 2011, 332, 1330–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolero, A.; Faeh, D.; Paccaud, F.; Cornuz, J. Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbulo, L.; Palipudi, K.M.; Smith, T.; Yin, S.; Munish, V.G.; Sinha, D.N.; Gupta, P.C.; Swasticharan, L. Patterns and related factors of bidi smoking in India. Tob. Prev. Cessation 2020, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.M. Comparison between smokers and smokeless tobacco users in their past attempts and intentions to quit: Analysis of two rounds of a national survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 13662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim-Mozeleski, J.E.; Pandey, R. The intersection of food insecurity and tobacco use: A scoping review. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 124S–138S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Mozeleski, J.E.; Pandey, R.; Tsoh, J.Y. Psychological distress and cigarette smoking among US households by income: Considering the role of food insecurity. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 1, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, A.; Oyebode, O.; Satterthwaite, D.; Chen, Y.F.; Ndugwa, R.; Sartori, J.; Mberu, B.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Haregu, T.; Watson, S.I.; et al. The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. Lancet 2017, 389, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R. Social identity as a driver of adult chronic energy deficiency: Analysis of rural Indian households. J. Public Health Policy 2020, 4, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, B.; Adhikary, M.; Singha, S.R.; Parmar, D. Who is Anaemic in India? Intersections of class, caste, and gender. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2024, 56, 731–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Liu, Q.; Xue, H. Association between household fuel types and undernutrition status of adults and children under 5 years in 14 low- and middle-income countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 054079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.W.; Ko, Y.; Oh, J.Y.; Jeong, Y.J.; Lee, E.H.; Yang, B.; Lee, K.M.; Shn, J.F.; et al. Effects of underweight and overweight on mortality in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1236099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Jain, P.; Singh, N.; Singh, L.; Kumar, C.; Yadav, A.; Subramanian, S.V.; Singh, S. Social desirability and under-reporting of smokeless tobacco use among reproductive age woman: Evidence from National Family Health Survey. SSM-Popul. Health 2022, 19, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Full Sample | Subsamples Based on Underweight Status | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 27,902) | Number | No (n = 21,456) | Yes (n = 6446) | ||

| Underweight | |||||

| No | 73.1% | 21,456 | |||

| Yes | 27.0% | 6446 | |||

| Tobacco use | |||||

| No | 65.3% | 18,962 | 81.6% | 18.4% | |

| Smoking | 12.3% | 3428 | 63.1% | 36.9% | |

| Smokeless | 19.6% | 4719 | 70.0% | 30.0% | |

| Both | 2.8% | 793 | 65.3% | 34.6% | <0.001 |

| Food insecure | |||||

| No | 89.4% | 25,440 | 77.9% | 22.6% | |

| Yes | 10.6% | 2462 | 66.1% | 33.9% | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||

| 60–69 | 60.0% | 17,140 | 79.9% | 20.1% | |

| 70–79 | 29.8% | 8038 | 74.2% | 25.8% | |

| 80+ | 10.3% | 2724 | 66.0% | 34.0% | <0.001 |

| Female | |||||

| No | 47.7% | 13,487 | 76.3% | 23.7% | |

| Yes | 52.3% | 14,415 | 77.5% | 22.6% | 0.023 |

| Urban residence | |||||

| No | 72.4% | 18,715 | 71.1% | 28.9% | |

| Yes | 27.6% | 9187 | 88.7% | 11.3% | <0.001 |

| Currently married | |||||

| Yes | 62.7% | 17,891 | 78.9% | 21.1% | |

| No | 37.3% | 10,011 | 73.3% | 26.7% | <0.001 |

| Region | |||||

| North | 13.0% | 5143 | 82.0% | 18.0% | |

| Central | 21.2% | 3750 | 63.8% | 36.2% | |

| East | 24.6% | 5233 | 68.3% | 31.7% | |

| Northeast | 3.0% | 3659 | 77.6% | 22.4% | |

| West | 16.6% | 3586 | 80.0% | 20.0% | |

| South | 21.5% | 6531 | 85.2% | 14.8% | <0.001 |

| Education attainment | |||||

| No schooling | 56.7% | 14,961 | 70.3% | 29.8% | |

| Middle or less | 29.4% | 8797 | 81.1% | 18.9% | |

| At least secondary | 13.9% | 4144 | 92.0% | 8.0% | <0.001 |

| Currently working | |||||

| Yes | 32.2% | 8460 | 74.6% | 25.4% | |

| No | 67.8% | 19,442 | 77.9% | 22.1% | <0.001 |

| Caste | |||||

| Scheduled Tribe | 8.5% | 4681 | 72.5% | 27.5% | |

| Scheduled Caste | 19.3% | 4572 | 70.4% | 29.6% | |

| Other backward class | 45.1% | 10,703 | 76.4% | 23.6% | |

| None of above | 27.1% | 7946 | 83.9% | 16.1% | <0.001 |

| Religion | |||||

| Hindu | 82.2% | 20,345 | 74.9% | 25.1% | |

| Muslim | 11.3% | 3262 | 80.9% | 19.2% | |

| Christian | 2.8% | 2816 | 82.9% | 17.1% | |

| Others | 3.7% | 1479 | 84.6% | 15.4% | <0.001 |

| Wealth quintiles (MPCE) | |||||

| Lowest | 21.8% | 5689 | 68.6% | 31.4% | |

| Second | 21.8% | 5764 | 71.8% | 28.2% | |

| Middle | 20.9% | 5738 | 77.4% | 22.6% | |

| Fourth | 19.1% | 5495 | 81.4% | 18.6% | |

| Highest | 16.4% | 5216 | 86.1% | 13.9% | <0.001 |

| Poor self-rated health | |||||

| No | 76.3% | 21,678 | 77.7% | 22.3% | |

| Yes | 23.7% | 6224 | 74.0% | 26.0% | <0.001 |

| Chewing disability | |||||

| No | 66.8% | 18,995 | 80.5% | 19.5% | |

| Yes | 33.2% | 8932 | 69.2% | 30.8% | <0.001 |

| 1+ ADL | |||||

| No | 77.9% | 22,448 | 77.4% | 22.6% | |

| Yes | 22.1% | 5454 | 74.9% | 25.1% | <0.001 |

| 1+ IADL | |||||

| No | 53.1% | 15,938 | 79.7% | 20.3% | |

| Yes | 46.9% | 11,964 | 73.1% | 26.9% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 67.8% | 18,194 | 71.5% | 28.5% | |

| Yes | 32.2% | 9708 | 87.1% | 13.0% | <0.001 |

| Stroke | |||||

| No | 97.6% | 27,277 | 76.7% | 23.3% | |

| Yes | 2.4% | 625 | 85.4% | 14.6% | <0.001 |

| Chronic heart diseases | |||||

| No | 94.7% | 26,499 | 76.2% | 23.8% | |

| Yes | 5.29% | 1403 | 89.6% | 10.4% | <0.001 |

| Cancer | |||||

| No | 99.4% | 27,703 | 76.9% | 23.2% | |

| Yes | 0.6% | 199 | 82.9% | 17.1% | 0.043 |

| Chronic lung disease | |||||

| No | 91.6% | 25,823 | 77.5% | 22.5% | |

| Yes | 8.36% | 2079 | 69.6% | 30.5% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | |||||

| No | 86.1% | 23,638 | 74.0% | 26.0% | |

| Yes | 13.9% | 4264 | 92.9% | 7.1% | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | |||||

| No | 80.8% | 22,994 | 75.5% | 24.5% | |

| Yes | 19.2% | 4908 | 83.3% | 16.7% | <0.001 |

| Jaundice/hepatitis | |||||

| No | 97.5% | 27,151 | 77.2% | 22.8% | |

| Yes | 2.5% | 751 | 64.5% | 35.6% | <0.001 |

| Tuberculosis | |||||

| No | 98.9% | 27,622 | 77.1% | 22.9% | |

| Yes | 1.14% | 280 | 53.6% | 46.4% | <0.001 |

| Malaria | |||||

| No | 91.2% | 25,755 | 77.9% | 22.1% | |

| Yes | 8.9% | 2147 | 65.1% | 34.9% | <0.001 |

| Diarrhoea/gastroenteritis | |||||

| No | 84.8% | 24,080 | 77.7% | 22.3% | |

| Yes | 15.3% | 3822 | 71.8% | 28.2% | <0.001 |

| Anemia | |||||

| No | 95.5% | 26,812 | 77.3% | 22.7% | |

| Yes | 4.5% | 1090 | 67.3% | 32.7% | <0.001 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Full Sample | Male Subsample | Female Subsample | Rural Subsample | Urban Subsample |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Tobacco use (ref: No) | |||||

| Smoking | 2.07 *** (1.79, 2.40) | 1.93 *** (1.62, 2.31) | 2.15 *** (1.65, 2.80) | 2.17 *** (1.85, 2.55) | 1.57 ** (1.07, 2.30) |

| Smokeless | 1.26 *** (1.11, 1.42) | 1.07 (0.89, 1.29) | 1.46 *** (1.24, 1.73) | 1.27 *** (1.11, 1.45) | 1.15 (0.84, 1.57) |

| Both | 1.74 *** (1.36, 2.22) | 1.55 *** (1.18, 2.04) | 4.26 *** (2.19, 8.28) | 1.79 *** (1.38, 2.33) | 1.55 (0.75, 3.17) |

| Food insecure | 1.27 *** (1.10, 1.48) | 1.39 *** (1.11, 1.75) | 1.15 (0.95, 1.39) | 1.26 *** (1.07, 1.48) | 1.36 * (0.95, 1.95) |

| Controls: | |||||

| Age (ref: 60–69) | |||||

| 70–79 | 1.19 *** (1.07, 1.33) | 1.25 *** (1.08, 1.46) | 1.14 (0.97, 1.33) | 1.20 *** (1.06, 1.35) | 1.25 * (0.96, 1.63) |

| 80+ | 1.76 *** (1.44, 2.14) | 1.84 *** (1.42, 2.38) | 1.71 *** (1.28, 2.28) | 1.63 *** (1.35, 1.97) | 2.70 *** (1.53, 4.76) |

| Female | 0.83 *** (0.74, 0.94) | - | - | 0.86 ** (0.75, 0.98) | 0.70 ** (0.52, 0.93) |

| Urban residence | 0.50 *** (0.44, 0.58) | 0.49 *** (0.41, 0.59) | 0.53 *** (0.43, 0.65) | - | - |

| Not currently married | 1.31 *** (1.18, 1.46) | 1.27 *** (1.07, 1.50) | 1.31 *** (1.13, 1.52) | 1.32 *** (1.17, 1.48) | 1.30 * (0.99, 1.70) |

| Region (ref: North) | |||||

| Central | 1.74 *** (1.50, 2.02) | 2.05 *** (1.65, 2.56) | 1.49 *** (1.21, 1.83) | 1.79 *** (1.52, 2.12) | 1.54 ** (1.11, 2.15) |

| East | 1.67 *** (1.44, 1.94) | 1.55 *** (1.24, 1.94) | 1.83 *** (1.50, 2.23) | 1.78 *** (1.51, 2.09) | 1.12 (0.78, 1.60) |

| Northeast | 1.60 *** (1.33, 1.93) | 1.43 ** (1.08, 1.90) | 1.67 *** (1.29, 2.17) | 1.74 *** (1.42, 2.12) | 0.98 (0.54, 1.77) |

| West | 1.30 *** (1.09, 1.56) | 1.21 (0.93, 1.56) | 1.39 ** (1.07, 1.79) | 1.37 *** (1.11, 1.68) | 1.02 (0.69, 1.51) |

| South | 1.00 (0.84, 1.19) | 0.98 (0.78, 1.23) | 1.01 (0.77, 1.33) | 1.02 (0.86, 1.22) | 0.84 (0.53, 1.33) |

| Education (ref: No schooling) | |||||

| Middle or less | 0.74 *** (0.66, 0.83) | 0.78 *** (0.67, 0.90) | 0.69 *** (0.56, 0.85) | 0.76 *** (0.67, 0.87) | 0.64 *** (0.48, 0.86) |

| At least secondary | 0.45 *** (0.36, 0.57) | 0.48 *** (0.37, 0.62) | 0.26 *** (0.15, 0.45) | 0.52 *** (0.39, 0.69) | 0.31 *** (0.20, 0.46) |

| Not currently working | 1.04 (0.93, 1.17) | 1.04 (0.89, 1.21) | 1.00 (0.85, 1.19) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14) | 1.33 * (0.99, 1.78) |

| Caste (ref: ST) | |||||

| Scheduled Caste | 0.85 * (0.71, 1.02) | 0.856 (0.65, 1.11) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.08) | 0.84 * (0.69, 1.02) | 0.83 (0.44, 1.59) |

| Other backward class | 0.78 *** (0.66, 0.93) | 0.74 ** (0.58, 0.95) | 0.83 (0.65, 1.04) | 0.78 *** (0.66, 0.93) | 0.69 (0.37, 1.26) |

| None of above | 0.61 *** (0.51, 0.74) | 0.62 *** (0.47, 0.81) | 0.61 *** (0.47, 0.78) | 0.63 *** (0.52, 0.77) | 0.49 ** (0.27, 0.91) |

| Religion (ref: Hindu) | |||||

| Muslim | 0.88 (0.75, 1.03) | 0.80 * (0.64, 1.00) | 0.96 (0.78, 1.19) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.04) | 0.90 (0.65, 1.26) |

| Christian | 0.81 (0.62, 1.07) | 0.91 (0.59, 1.40) | 0.74 (0.50, 1.07) | 0.798 (0.59, 1.07) | 0.98 (0.51, 1.90) |

| Others | 0.96 (0.73, 1.26) | 1.23 (0.85, 1.78) | 0.72 (0.48, 1.08) | 0.94 (0.70, 1.25) | 1.09 (0.56, 2.11) |

| Wealth quintile (ref: Lowest) | |||||

| Second | 0.91 (0.79, 1.05) | 1.03 (0.84, 1.25) | 0.82 * (0.68, 1.00) | 0.94 (0.81, 1.09) | 0.81 (0.58, 1.14) |

| Middle | 0.80 *** (0.69, 0.93) | 0.80 ** (0.64, 0.99) | 0.82 * (0.67, 1.02) | 0.83 ** (0.71, 0.97) | 0.69 * (0.46, 1.03) |

| Fourth | 0.61 *** (0.52, 0.71) | 0.65 *** (0.52, 0.81) | 0.57 *** (0.46, 0.71) | 0.63 *** (0.53, 0.74) | 0.58 ** (0.38, 0.88) |

| Highest | 0.51 *** (0.43, 0.61) | 0.52 *** (0.40, 0.66) | 0.53 *** (0.42, 0.67) | 0.52 *** (0.43, 0.63) | 0.53 ** (0.32, 0.88) |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.27 *** (1.12, 1.43) | 1.23 ** (1.04, 1.47) | 1.29 *** (1.09, 1.53) | 1.24 *** (1.09, 1.41) | 1.44 ** (1.03, 2.00) |

| 1+ ADL | 0.99 (0.87, 1.13) | 0.99 (0.81, 1.22) | 1.01 (0.85, 1.19) | 1.05 (0.91, 1.21) | 0.76 * (0.55, 1.04) |

| 1+ IADL | 1.14 ** (1.02, 1.28) | 1.14 * (0.97, 1.33) | 1.14 * (0.98, 1.34) | 1.19 *** (1.06, 1.34) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.25) |

| Chewing disability | 1.29 *** (1.16, 1.42) | 1.22 *** (1.06, 1.42) | 1.33 *** (1.15, 1.53) | 1.26 *** (1.13, 1.41) | 1.44 *** (1.12, 1.84) |

| Hypertension | 0.56 *** (0.49, 0.63) | 0.53 *** (0.45, 0.63) | 0.58 *** (0.49, 0.69) | 0.57 *** (0.50, 0.64) | 0.52 *** (0.38, 0.71) |

| Stroke | 0.78 (0.56, 1.10) | 0.79 (0.51, 1.24) | 0.77 (0.48, 1.23) | 0.87 (0.60, 1.25) | 0.34 ** (0.13, 0.89) |

| Chronic heart diseases | 0.66 ** (0.48, 0.91) | 0.73 (0.47, 1.12) | 0.59 ** (0.38, 0.90) | 0.71 * (0.50, 1.02) | 0.50 * (0.24, 1.02) |

| Cancer | 0.95 (0.53, 1.70) | 1.08 (0.43, 2.72) | 0.80 (0.37, 1.72) | 0.95 (0.46, 1.97) | 1.02 (0.40, 2.58) |

| Chronic lung disease | 1.69 *** (1.46, 1.97) | 2.18 *** (1.79, 2.67) | 1.25 ** (1.00, 1.56) | 1.66 *** (1.40, 1.97) | 1.83 *** (1.34, 2.52) |

| Diabetes | 0.41 *** (0.34, 0.50) | 0.52 *** (0.41, 0.67) | 0.31 *** (0.23, 0.42) | 0.44 *** (0.35, 0.55) | 0.33 *** (0.23, 0.48) |

| Arthritis | 0.69 *** (0.61, 0.79) | 0.89 (0.74, 1.07) | 0.55 *** (0.46, 0.66) | 0.73 *** (0.63, 0.84) | 0.52 *** (0.38, 0.71) |

| Jaundice/Hepatitis | 1.30 * (0.99, 1.72) | 1.26 (0.86, 1.82) | 1.34 (0.90, 1.98) | 1.19 (0.88, 1.61) | 2.14 ** (1.08, 4.22) |

| Tuberculosis | 2.17 *** (1.36, 3.47) | 2.24 *** (1.24, 4.04) | 2.38 *** (1.29, 4.40) | 2.2 *** (1.29, 3.74) | 2.12 * (0.97, 4.63) |

| Malaria | 1.19 ** (1.02, 1.40) | 1.36 ** (1.08, 1.73) | 1.05 (0.85, 1.29) | 1.20 ** (1.01, 1.42) | 1.28 (0.81, 2.03) |

| Diarrhoea/gastroenteritis | 0.93 (0.81, 1.07) | 0.80 ** (0.66, 0.98) | 1.06 (0.88, 1.27) | 0.94 (0.81, 1.09) | 0.94 (0.67, 1.32) |

| Anemia | 1.47 *** (1.19, 1.81) | 1.77 *** (1.30, 2.40) | 1.35 ** (1.01, 1.80) | 1.53 *** (1.22, 1.92) | 1.08 (0.62, 1.86) |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.148 | 0.157 | 0.153 | 0.105 | 0.178 |

| Observations | 27,902 | 13,487 | 14,415 | 18,715 | 9187 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Tobacco use (ref: No) | ||

| Smoking | 1.86 *** (1.55, 2.22) | 1.62 *** (1.25, 2.11) |

| Smokeless | 1.28 *** (1.11, 1.478) | 1.09 (0.87, 1.37) |

| Both | 1.69 *** (1.23, 2.32) | 1.09 (0.70, 1.68) |

| Education (ref: No schooling) | ||

| Middle or less | 0.70 *** (0.59, 0.82) | 0.74 *** (0.66, 0.83) |

| At least secondary | 0.46 *** (0.34, 0.62) | 0.45 *** (0.36, 0.57) |

| Wealth quintile (ref: Lowest) | ||

| Second quintile | 0.92 (0.80, 1.05) | 0.83 * (0.68, 1.00) |

| Middle quintile | 0.80 *** (0.69, 0.94) | 0.76 ** (0.62, 0.94) |

| Fourth quintile | 0.61 *** (0.52, 0.71) | 0.48 *** (0.39, 0.60) |

| Highest quintile | 0.52 *** (0.43, 0.62) | 0.46 *** (0.37, 0.58) |

| Interaction terms for tobacco use: | ||

| Tobacco use and Education (ref: No tobacco#no schooling) | - | |

| Smoking tobacco#Middle or less | 1.33 * (0.99, 1.79) | |

| Smoking tobacco#At least secondary | 1.27 (0.74, 2.15) | |

| Smokeless tobacco#Middle or less | 1.02 (0.78, 1.33) | |

| Smokeless tobacco#At least secondary | 0.76 (0.47, 1.22) | |

| Both tobacco #Middle or less | 1.13 (0.69, 1.85) | |

| Both tobacco #At least secondary | 0.88 (0.36, 2.19) | |

| Tobacco use and Wealth (ref: No tobacco#lowest quintile) | - | |

| Smoking tobacco#second quintile | 1.37 (0.94, 2.00) | |

| Smoking tobacco#middle quintile | 1.12 (0.75, 1.66) | |

| Smoking tobacco#fourth quintile | 1.70 ** (1.12, 2.57) | |

| Smoking tobacco#highest quintile | 1.47 * (0.95, 2.28) | |

| Smokeless tobacco#second quintile | 1.20 (0.87, 1.64) | |

| Smokeless tobacco#middle quintile | 1.09 (0.77, 1.53) | |

| Smokeless tobacco#fourth quintile | 1.55 ** (1.08, 2.22) | |

| Smokeless tobacco#highest quintile | 1.13 (0.73, 1.75) | |

| Both tobacco#second quintile | 1.52 (0.82, 2.80) | |

| Both tobacco#middle quintile | 1.69 (0.89, 3.18) | |

| Both tobacco#fourth quintile | 2.97 *** (1.55, 5.70) | |

| Both tobacco#highest quintile | 1.71 (0.66, 4.42) | |

| Observations | 27,902 | 27,902 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Selvamani, Y.; Pradhan, J.; Fong, J.H. Tobacco Use, Food Insecurity, and Low BMI in India’s Older Population. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16213649

Selvamani Y, Pradhan J, Fong JH. Tobacco Use, Food Insecurity, and Low BMI in India’s Older Population. Nutrients. 2024; 16(21):3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16213649

Chicago/Turabian StyleSelvamani, Yesuvadian, Jalandhar Pradhan, and Joelle H. Fong. 2024. "Tobacco Use, Food Insecurity, and Low BMI in India’s Older Population" Nutrients 16, no. 21: 3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16213649

APA StyleSelvamani, Y., Pradhan, J., & Fong, J. H. (2024). Tobacco Use, Food Insecurity, and Low BMI in India’s Older Population. Nutrients, 16(21), 3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16213649