Effects of Responsiveness and Responsibility Parenting Factors on Family Mealtime Outcomes in Overweight African American Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Demographic Information

2.4.2. Adolescent-Reported Parenting Style

2.4.3. Parent-Reported Child Feeding Questionnaire

- Adolescent-Reported Parental Responsibility

- b.

- Adolescent-Reported Parental Monitoring

2.4.4. Frequency and Quality of Family Mealtimes

2.5. Data Analytic Plan

Multilevel Model Building

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Correlation Analyses

3.3. Frequency of Family Mealtimes

3.4. Quality of Family Mealtimes

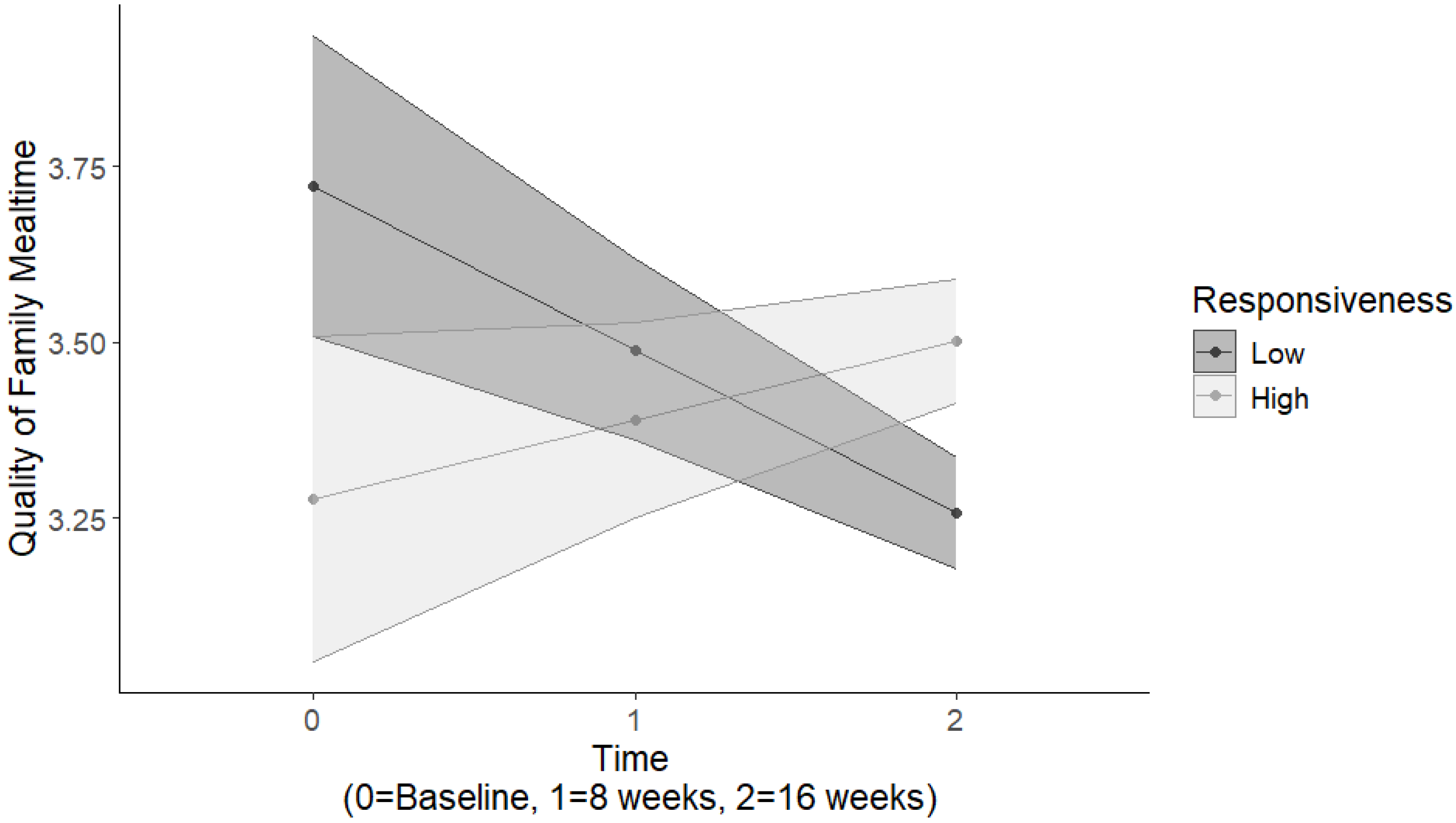

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dallacker, M.; Hertwig, R.; Mata, J. The frequency of family meals and nutritional health in children: A meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallacker, M.; Hertwig, R.; Mata, J. Quality matters: A meta-analysis on components of healthy family meals. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulkerson, J.A.; Story, M.; Mellin, A.; Leffert, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; French, S.A. Family Dinner Meal Frequency and Adolescent Development: Relationships with Developmental Assets and High-Risk Behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, S.M.; McCullough, M.B.; Rex, S.; Munafò, M.R.; Taylor, G. Family Meal Frequency, Diet, and Family Functioning: A Systematic Review With Meta-analyses. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, J.M. A review of familial correlates of child and adolescent obesity: What has the 21st century taught us so far? Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2009, 21, 457–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Carter, E.; Telzer, E.H. Family meals buffer the daily emotional risk associated with family conflict. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 2110–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, J.M.; MacLehose, R.F.; Larson, N.; Laska, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Family Food Preparation and Its Effects on Adolescent Dietary Quality and Eating Patterns. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M. Family Meals during Adolescence Are Associated with Higher Diet Quality and Healthful Meal Patterns during Young Adulthood. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2007, 107, 1502–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, A.K.; Graubard, B.I. 20-Year trends in dietary and meal behaviors were similar in U.S. children and adolescents of different race/ethnicity. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1880–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Larson, N. Changes in the frequency of family meals from 1999 to 2010 in the homes of adolescents: Trends by sociodemographic characteristics. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.N.; Kerr, J.; Young, J.L. Associations between Obesity, Obesogenic Environments, and Structural Racism Vary by County-Level Racial Composition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lytle, L.A.; Hearst, M.O.; Fulkerson, J.; Murray, D.M.; Martinson, B.; Klein, E.; Pasch, K.; Samuelson, A. Examining the Relationships Between Family Meal Practices, Family Stressors, and the Weight of Youth in the Family. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 41, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zeller, M.H.; Reiter-Purtill, J.; Modi, A.C.; Gutzwiller, J.; Vannatta, K.; Davies, W.H. Controlled Study of Critical Parent and Family Factors in the Obesigenic Environment. Obesity 2007, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzman-Ulrich, H.; Wilson, D.K.; St George, S.M.; Lawman, H.; Segal, M.; Fairchild, A. The integration of a family systems approach for understanding youth obesity, physical activity, and dietary programs. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 13, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.K.; Sweeney, A.M.; Kitzman-Ulrich, H.; Gause, H.; St George, S.M. Promoting Social Nurturance and Positive Social Environments to Reduce Obesity in High-Risk Youth. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 20, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglan, A.; Flay, B.R.; Embry, D.D.; Sandler, I.N. The Critical Role of Nurturing Environments for Promoting Human Wellbeing. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev. Psychol. 1971, 4 Pt 2, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Socialization, Personality and Social Development; Mussen, P., Hetherington, E.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1983; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Shloim, N.; Edelson, L.R.; Martin, N.; Hetherington, M.M. Parenting Styles, Feeding Styles, Feeding Practices, and Weight Status in 4–12 Year-Old Children: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.K.; Sweeney, A.M.; Quattlebaum, M.; Loncar, H.; Kipp, C.; Brown, A. The Moderating Effects of the Families Improving Together (FIT) for Weight Loss Intervention and Parenting Factors on Family Mealtime in Overweight and Obese African American Adolescents. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loncar, H.; Wilson, D.K.; Sweeney, A.M.; Quattlebaum, M.; Zarrett, N. Associations of parenting factors and weight related outcomes in African American adolescents with overweight and obesity. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 44, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, J.M.; Wall, M.; Loth, K.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Parenting style as a predictor of adolescent weight and weight-related behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, E.T.; Wilder, T.; Beech, B.M.; Bruce, M.A. Caregiver Feeding Practices and Weight Status among African American Adolescents: The Jackson Heart KIDS Pilot Study. Eat. Behav. 2017, 27, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleddens, E.F.C.; Gerards, S.M.P.L.; Thijs, C.; de Vries, N.K.; Kremers, S.P.J. General parenting, childhood overweight and obesity-inducing behaviors: A review. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, e12–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardakani, A.; Monroe-Lord, L.; Wakefield, D.; Castor, C. Parenting Styles, Food Parenting Practices, Family Meals, and Weight Status of African American Families. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, A.E.; Ward, D.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Faith, M.S.; Hughes, S.O.; Kremers, S.P.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R.; O’connor, T.M.; Patrick, H.; Power, T.G. Fundamental constructs in food parenting practices: A content map to guide future research. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.L.; Hennessy, E.; Landry, A.S.; Goodman, M.H. Patterns of Food Parenting Practices Regarding Fruit and Vegetables among Parent-Adolescent Dyads. Child. Obes. 2020, 16, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuemmeler, B.F.; Yang, C.; Costanzo, P.; Hoyle, R.H.; Siegler, I.C.; Williams, R.B.; Østbye, T. Parenting Styles and Body Mass Index Trajectories From Adolescence to Adulthood. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, R.L.; Mobley, A.R. Parenting styles, feeding styles, and their influence on child obesogenic behaviors and body weight. A review. Appetite 2013, 71, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.K.; Kitzman-Ulrich, H.; Resnicow, K.; Van Horn, M.L.; George, S.M.S.; Siceloff, E.R.; Alia, K.A.; McDaniel, T.; Heatley, V.; Huffman, L.; et al. An overview of the Families Improving Together (FIT) for weight loss randomized controlled trial in African American families. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2015, 42, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.K.; Sweeney, A.M.; Van Horn, M.L.; Kitzman, H.; Law, L.H.; Loncar, H.; Kipp, C.; Brown, A.; Quattlebaum, M.; McDaniel, T.; et al. The Results of the Families Improving Together (FIT) for Weight Loss Randomized Trial in Overweight African American Adolescents. Ann. Behav. Med. 2022, 56, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, N.E. The Relationship between Family Environment and Parenting Style: A Preliminary Study of African American Families. J. Black Psychol. 1995, 21, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamis-LeMonda, C.S.; Briggs, R.D.; McClowry, S.G.; Snow, D.L. Challenges to the study of African American parenting: Conceptualization, sampling, research approaches, measurement, and design. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2008, 8, 319–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe-Lord, L.; Jones, B.L.; Richards, R.; Reicks, M.; Gunther, C.; Banna, J.; Topham, G.L.; Anderson, A.; Lora, K.R.; Wong, S.S.; et al. Parenting Practices and Adolescents’ Eating Behaviors in African American Families. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe-Lord, L.; Anderson, A.; Jones, B.L.; Richards, R.; Reicks, M.; Gunther, C.; Banna, J.; Topham, G.L.; Lora, K.R.; Wong, S.S.; et al. Relationship between Family Racial/Ethnic Backgrounds, Parenting Practices and Styles, and Adolescent Eating Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querido, J.G.; Warner, T.D.; Eyberg, S.M. Parenting styles and child behavior in African American families of preschool children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2002, 31, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCuyer, E.A.; Swanson, D.P. A Within-Group Analysis of African American Mothers’ Authoritarian Attitudes, Limit-Setting and Children’s Self-Regulation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, L.G.; Simons, R.L.; Su, X. Consequences of corporal punishment among African Americans: The importance of context and outcome. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, J.G.; Abernethy, A.; Harris, A. Adolescent–parent interactions in middle-class African American families: Longitudinal change and contextual variations. J. Fam. Psychol. 2000, 14, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L.L.; Fisher, J.O.; Grimm-Thomas, K.; Markey, C.N.; Sawyer, R.; Johnson, S.L. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite 2001, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, B.Y.; Savage, J.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Birch, L.L. Alternatives to restrictive feeding practices to promote self-regulation in childhood: A developmental perspective. Pediatr. Obes. 2016, 11, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.C.; Kolko, R.P.; Stein, R.I.; Welch, R.R.; Perri, M.G.; Schechtman, K.B.; Saelens, B.E.; Epstein, L.H.; Wilfley, D.E. Modifications in parent feeding practices and child diet during family-based behavioral treatment improve child zBMI. Obesity 2014, 22, E119–E126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.; Richter, R.; Brauhardt, A.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W.; Hilbert, A. Parental feeding practices in families with children aged 2-13 years: Psychometric properties and child age-specific norms of the German version of the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ). Appetite 2017, 109, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, L.E.; Wilson, D.K.; Kitzman-Ulrich, H.; Lyerly, J.E.; Gause, H.M.; Resnicow, K. Associations between Culturally Relevant Recruitment Strategies and Participant Interest, Enrollment and Generalizability in a Weight-loss Intervention for African American Families. Ethn. Dis. 2016, 26, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States; Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2002.

- Jackson, C.; Henriksen, L.; Foshee, V.A. The Authoritative Parenting Index: Predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, L.E.; Wilson, D.K.; Van Horn, M.L.; Pate, R.R. Associations Between Parenting Factors, Motivation, and Physical Activity in Overweight African American Adolescents. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Li, C.; Nazir, N.; Choi, W.S.; Resnicow, K.; Birch, L.L.; Ahluwalia, J.S. Confirmatory factor analysis of the child-feeding questionnaire among parents of adolescents. Appetite 2006, 47, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Larson, N.I.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Story, M. Family meals and adolescents: What have we learned from Project EAT (Eating Among Teens)? Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, J.M.; Rowley, S.; Trofholz, A.; Hanson, C.; Rueter, M.; MacLehose, R.F.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Childhood obesity and interpersonal dynamics during family meals. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, J.; Larson, N.; Berge, J.M.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Family meals among parents: Associations with nutritional, social and emotional wellbeing. Prev. Med. 2018, 113, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.L. Making time for family meals: Parental influences, home eating environments, barriers and protective factors. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 193, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boles, R.E.; Gunnarsdottir, T. Family Meals Protect against Obesity: Exploring the Mechanisms. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, J.M.; Wall, M.; Hsueh, T.F.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Larson, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. The Protective Role of Family Meals for Youth Obesity: 10-Year Longitudinal Associations. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moens, E.; Braet, C.; Bosmans, G.; Rosseel, Y. Unfavourable family characteristics and their associations with childhood obesity: A cross-sectional study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2009, 17, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.M.; Kasprzak, C.M.; Mansouri, T.H.; Gregory, A.M.; Barich, R.A.; Hatzinger, L.A.; Leone, L.A.; Temple, J.L. An Ecological Perspective of Food Choice and Eating Autonomy Among Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 654139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Farris, K.L.; Sun, M.C.; Dailey, R.M.; Donovan, E.E. Parenting Practices, Autonomous Motivation, and Adolescent Diet Habits. J. Res. Adolesc. 2020, 30, 800–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balantekin, K.N.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Francis, L.A.; Ventura, A.K.; Fisher, J.O.; Johnson, S.L. Positive parenting approaches and their association with child eating and weight: A narrative review from infancy to adolescence. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, A.; Obita, G. Childhood Obesity and Its Comorbidities in High-Risk Minority Populations: Prevalence, Prevention and Lifestyle Intervention Guidelines. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obita, G.; Alkhatib, A. Effectiveness of Lifestyle Nutrition and Physical Activity Interventions for Childhood Obesity and Associated Comorbidities among Children from Minority Ethnic Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Kit, B.K.; Flegal, K.M. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 2014, 311, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Adolescent Age M(SD) | 12.83 (1.75) |

| Adolescent Sex (Female), N% | 153 (64%) |

| Parent Education, N% | |

| 9 to 11 Years | 6 (2.5%) |

| 12 Years | 33 (13.7%) |

| Some College | 99 (41.1%) |

| 4 Year College | 45 (18.7%) |

| Professional | 55 (22.8%) |

| Parent BMI M(SD) | 37.49 (8.34) |

| Parent Age M(SD) | 43.18 (8.65) |

| Parent Income, N% | |

| Less than $10,000 | 36 (14.9%) |

| $10,000–$24,000 | 46 (19.1%) |

| $25,000–$39,000 | 65 (27.0%) |

| $40,000–$54,000 | 31 (12.9%) |

| $55,000–$69,000 | 21 (8.7%) |

| $70,000–$84,000 | 12 (5.0%) |

| $85,000 or greater | 24 (10.0%) |

| Parents Married, N(%) | 83 (34.4%) |

| Children in Home, M(SD) | 2.05 (1.20) |

| Adolescent BMI Percentile M(SD) | 96.61 (4.25) |

| Variable | Baseline (0 Weeks) | Post-Intervention (8 Weeks) | Post-Online (16 Weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsiveness | 4.38 (1.02) | 4.32 (1.26) | 4.19 (1.38) |

| Demandingness | 5.20 (0.80) | 5.02 (0.86) | 4.91 (1.12) |

| Responsibility | 2.85 (0.51) | 2.86 (0.53) | 2.99 (0.52) |

| Monitoring | 2.82 (0.98) | 3.06 (0.97) | 3.18 (0.97) |

| Freq. Family Meals (meals/week) | 3.46 (1.61) | 3.44 (1.55) | 3.24 (1.52) |

| Qual. Family Meals | 3.26 (0.65) | 3.35 (0.61) | 3.17 (0.76) |

| Estimate | SE | p-Value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.18 | 0.11 | 0.109 | −0.40 | 0.04 |

| Group Randomization | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.871 | −0.14 | 0.16 |

| Online Randomization | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.380 | −0.07 | 0.19 |

| Child Age | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.452 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| Child Sex | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.122 | −0.03 | 0.25 |

| Parent Education | 0.27 | 0.07 | <0.01 * | 0.13 | 0.40 |

| Parent BMI | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.424 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Time | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.703 | −0.09 | 0.06 |

| Responsiveness | 0.41 | 0.10 | <0.001 * | 0.21 | 0.60 |

| Demandingness | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.966 | −0.20 | 0.19 |

| Responsibility | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.045 * | 0.01 | 0.40 |

| Monitoring | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.839 | −0.22 | 0.17 |

| Time × Responsiveness | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.289 | −0.14 | 0.04 |

| Time × Demandingness | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.299 | −0.04 | 0.13 |

| Time × Responsibility | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.192 | −0.15 | 0.03 |

| Time × Monitoring | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.062 | 0.00 | 0.17 |

| Estimate | SE | p-Value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.32 | 0.19 | <0.001 | 2.96 | 3.68 |

| Group Randomization | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.065 | −0.01 | 0.44 |

| Online Randomization | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.350 | −0.11 | 0.32 |

| Child Age | −0.12 | 0.03 | <0.001 * | −0.19 | −0.06 |

| Child Sex | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.505 | −0.15 | 0.31 |

| Parent Education | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.150 | −0.06 | 0.39 |

| Parent BMI | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.095 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Time | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.185 | −0.23 | 0.04 |

| Responsiveness | −0.22 | 0.17 | 0.191 | −0.55 | 0.11 |

| Demandingness | 0.49 | 0.17 | 0.004 * | 0.16 | 0.82 |

| Responsibility | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.054 * | 0.00 | 0.67 |

| Monitoring | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.218 | −0.12 | 0.54 |

| Time × Responsiveness | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.026 * | 0.02 | 0.32 |

| Time × Demandingness | −0.25 | 0.08 | <0.001 * | −0.40 | −0.10 |

| Time × Responsiblity | −0.10 | 0.08 | 0.211 | −0.24 | 0.05 |

| Time × Monitoring | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.530 | −0.19 | 0.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loncar, H.; Sweeney, A.M.; White, T.; Quattlebaum, M.; Wilson, D.K. Effects of Responsiveness and Responsibility Parenting Factors on Family Mealtime Outcomes in Overweight African American Adolescents. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223874

Loncar H, Sweeney AM, White T, Quattlebaum M, Wilson DK. Effects of Responsiveness and Responsibility Parenting Factors on Family Mealtime Outcomes in Overweight African American Adolescents. Nutrients. 2024; 16(22):3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223874

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoncar, Haylee, Allison M. Sweeney, Taylor White, Mary Quattlebaum, and Dawn K. Wilson. 2024. "Effects of Responsiveness and Responsibility Parenting Factors on Family Mealtime Outcomes in Overweight African American Adolescents" Nutrients 16, no. 22: 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223874

APA StyleLoncar, H., Sweeney, A. M., White, T., Quattlebaum, M., & Wilson, D. K. (2024). Effects of Responsiveness and Responsibility Parenting Factors on Family Mealtime Outcomes in Overweight African American Adolescents. Nutrients, 16(22), 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223874