A Cross-Sectional Study Exploring the Role of Social Isolation in the Relationship Between Food Insecurity, Depressive Symptoms, and Resource Use Among Midwestern Rural Veterans in the U.S.

Abstract

1. Introduction

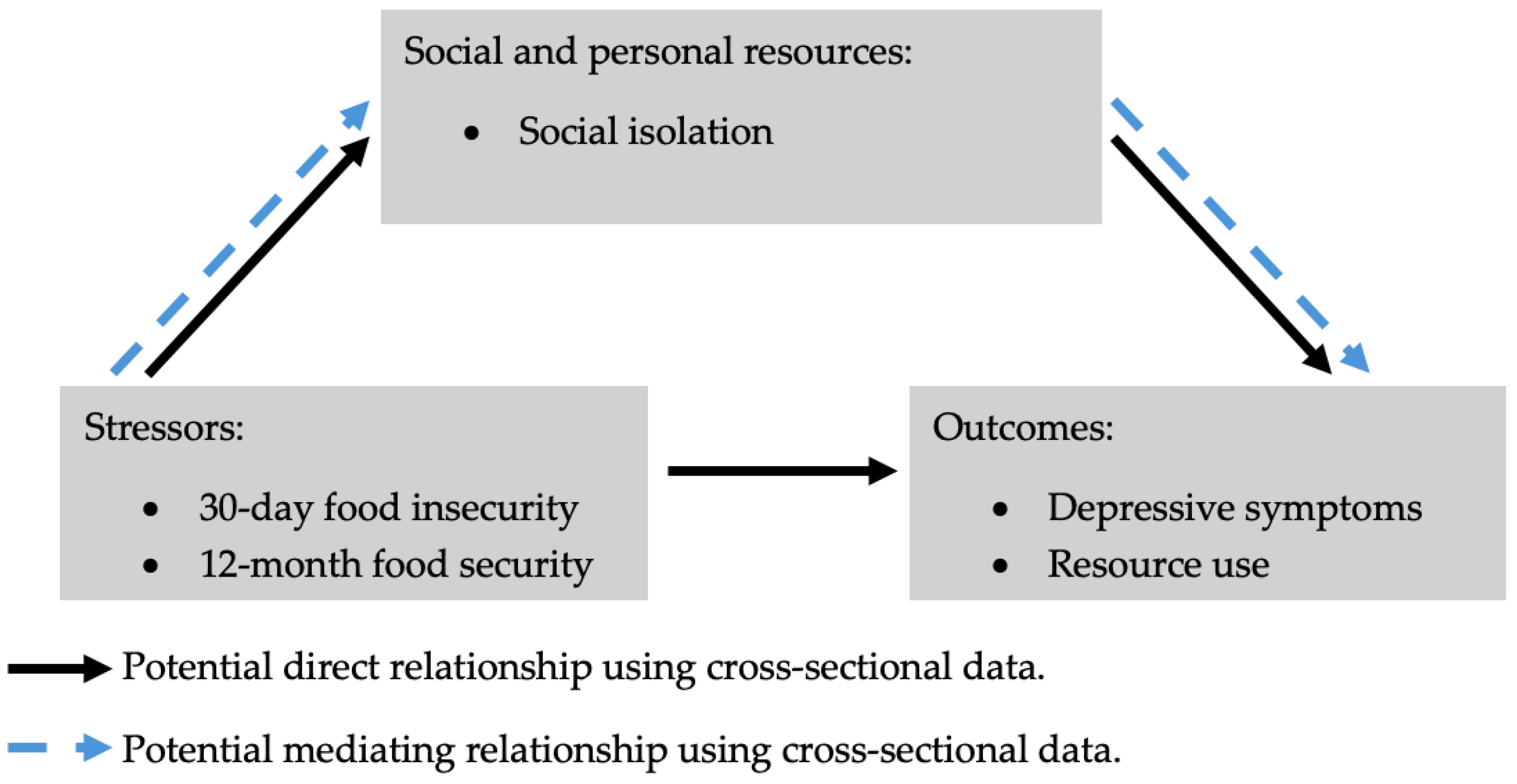

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Policy and Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- USDA ERS—Key Statistics & Graphics. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/ (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Determining Veteran Status. Verification Assistance Brief. Available online: https://www.va.gov/OSDBU/docs/Determining-Veteran-Status.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- S2101: Veteran Status—Census Bureau Table. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2022.S2101?q=Veterans&y=2022 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Rabbitt, M.P. Food Insecurity Among Working-Age Veterans. 2021. Available online: https://ers.usda.gov/sites/default/files/_laserfiche/publications/101269/ERR-829.pdf?v=39434 (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- United States Census Bureau. Veterans in Rural America: 2011–2015. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/acs/acs-36.html (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Ashe, K.M.; Lapane, K.L. Food Insecurity and Obesity: Exploring the Role of Social Support. J. Women’s Health 2018, 27, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.A.; McGinnis, K.A.; Goulet, J.; Bryant, K.; Gibert, C.; Leaf, D.A.; Mattocks, K.; Fiellin, L.E.; Vogenthaler, N.; Justice, A.C.; et al. Food Insecurity and Health: Data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Public Health Rep. 2015, 130, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, N.P.; Horning, M.L.; Geraci, J.C.; Uzdavines, A.W.; Helmer, D.A.; Hundt, N.E. Risk for depression and suicidal ideation among food insecure US veterans: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 2175–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, K.A.; Lutfiyya, M.N.; Kucharyski, C.J.; Grygelko, J.T.; Dillon, C.L.; Hill, T.J.; Rioux, M.P.; Huot, K.L. A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Depression and Health Service Deficits Between Rural and Nonrural U.S. Military Veterans. Mil. Med. 2015, 180, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VA.gov | Veterans Affairs-Rural Health Care Challenges. [General Information]. Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/care/toolkits/rural/ruralhealthcarechallenges.asp (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Ciolfi, M.L.; Jimenez, F. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older People: A Closer Look at Definitions. Available online: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1107&context=aging (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Grenawalt, T.A.; Lu, J.; Hamner, K.; Gill, C.; Umucu, E. Social isolation and well-being in veterans with mental illness. J. Ment. Health 2017, 32, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Berkowitz, S.A. Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Quality of Life Among Food-Insecure Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 67, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineau, C.; Williams, P.L.; Brady, J.; Waddington, M.; Frank, L. Exploring experiences of food insecurity, stigma, social exclusion, and shame among women in high-income countries: A narrative review. Can. Food Stud. Rev. Can. Études L’alimentation 2021, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drageset, J. Social Support. In Health Promotion in Health Care—Vital Theories and Research; Haugan, G., Eriksson, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585650/ (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) | Food and Nutrition Service. 2024. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Welfare Benefits or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) | USAGov. Available online: https://www.usa.gov/welfare-benefits (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- VA Disability Compensation. Veterans Affairs. Available online: https://www.va.gov/disability/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Hom, M.A.; Stanley, I.H.; Schneider, M.E.; Joiner, T.E. A systematic review of help-seeking and mental health service utilization among military service members. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 53, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.B.; Caporale-Berkowitz, N.A.; Parent, M.C.; Brownson, C.B. Grit is associated with decreased mental health help-seeking among student veterans. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 71, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Menaghan, E.G.; Lieberman, M.A.; Mullan, J.T. The Stress Process. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1981, 22, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA ERS—Rural Classifications. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/ (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Wright, B.N.; MacDermid Wadsworth, S.; Wellnitz, A.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. Reaching rural veterans: A new mechanism to connect rural, low-income US Veterans with resources and improve food security. J. Public Health 2019, 41, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Sneddon, D.A.; MacDermid Wadsworth, S.; Topp, D.; Sterrett, R.A.; Newton, J.R.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. Grit but Not Help-Seeking Was Associated with Food Insecurity among Low Income, at-Risk Rural Veterans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA ERS—Survey Tools. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/survey-tools/#household (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Food and Nutrition Service. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. 2000. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/research/guide-measuring-household-food-security-revised-2000 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- HealthMeasures. Available online: https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_instruments&view=measure&id=209 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- National Institutes of Health-Office of Strategic Coordination—The Common Fund. Research Tools | NIH Common Fund. Available online: https://commonfund.nih.gov/promis/tools (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Carlozzi, N.E.; Ianni, P.A.; Lange, R.T.; Brickell, T.A.; Kallen, M.A.; Hahn, E.A.; French, L.M.; Cella, D.; Miner, J.A.; Tulsky, D.S. Understanding health-related quality of life of caregivers of civilians and service members/veterans with Traumatic Brain Injury: Establishing the reliability and validity of PROMIS social health measures. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, S110–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HealthMeasures. Scoring Instructions. Available online: https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/calculate-scores/scoring-instructions (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Instrument: Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) | NIDA CTN Common Data Elements. Available online: https://cde.nida.nih.gov/instrument/fc216f70-be8e-ac44-e040-bb89ad433387 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Benefits Administration; Office of the Associate Deputy Under Secretary for Management. Office of Facilities, VA.gov | Veterans Affairs. Available online: https://benefits.va.gov/benefits/ (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Retirement Plans Benefits and Savings. DOL. Available online: https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/retirement (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Types of Retirement Plans | Internal Revenue Service. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-sponsor/types-of-retirement-plans (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Social Security in Retirement | SSA. Available online: https://www.ssa.gov/retirement (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Unemployment Benefits | USAGov. Available online: https://www.usa.gov/unemployment-benefits (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Indy.gov: Township Assistance. Available online: https://www.indy.gov/activity/township-assistance (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) | Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Find Meals | Meals on Wheels America. Available online: https://www.mealsonwheelsamerica.org/find-meals (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Get the Facts on Senior Centers and How They Serve Older Adults. Available online: https://www.ncoa.org/article/get-the-facts-on-senior-centers/ (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- The Emergency Food Assistance Program | Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/tefap/emergency-food-assistance-program (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- National School Lunch Program | Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/nslp (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, Z.I.; Jose, P.E.; Cornwell, E.Y.; Koyanagi, A.; Nielsen, L.; Hinrichsen, C.; Meilstrup, C.; Madsen, K.R.; Koushede, V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e62–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.; Leslie, C.; McGill, G.; Kiernan, M. Understanding Unique Factors of Social Isolation and Loneliness of Military Veterans: A Delphi Study [Report]. Northumbria University. Available online: https://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/40398/ (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Paul, C.J.; Paul, J.E.; Anderson, R.S. The Local Food Environment and Food Security: The Health Behavior Role of Social Capital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garasky, S.; Morton, L.W.; Greder, K.A. The Effects of the Local Food Environment and Social Support on Rural Food Insecurity. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2006, 1, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, M.; Kihlstrom, L.; Arce, K.S.; Prendergast, K.; Dobbins, J.; McGrath, E.; Renda, A.; Shannon, E.; Cordier, T.; Song, Y.; et al. Food Insecurity, Loneliness, and Social Support among Older Adults. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2021, 16, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, A.R.; Marsh, H.E.; Forsberg, C.W.; Nicolaidis, C.; Chen, J.I.; Newsom, J.; Saha, S.; Dobscha, S.K. Loneliness is closely associated with depression outcomes and suicidal ideation among military veterans in primary care. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 230, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distance Most Important Barrier for Rural-Residing Veterans Seeking Healthcare—Publication Brief. Available online: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/citations/PubBriefs/articles.cfm?RecordID=400 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Dastgeer, G.; ur Rehman, A.; Asghar, M.A. Selection and use of mediation testing methods; application in management sciences. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, C.; Hallgren, K.A.; Cole, A.; Chwastiak, L.; Cheng, S.C. The relationship among social support, food insecurity and mental health for adults with severe mental illness and type 2 diabetes: A survey study. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2024, 45, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, M.; Miller, M.; Ballard, T.; Mitchell, D.C.; Hung, Y.W.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H. Does social support modify the relationship between food insecurity and poor mental health? Evidence from thirty-nine sub-Saharan African countries. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N (%) | p-Value 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Food Secure | Food Insecure | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 352 (85.5) | 220 (88.3) | 132 (82.0) | 0.07 | |

| Female | 58 (14.2) | 29 (11.6) | 29 (18.0) | ||

| Age | |||||

| 18–64 years | 206 (50.1) | 94 (37.6) | 112 (69.6) | <0.0001 * | |

| ≥65 years | 205 (49.9) | 156 (62.4) | 49 (30.4) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 263 (64.2) | 170 (68.3) | 93 (57.8) | 0.03 * | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated/never married | 147 (35.8) | 79 (31.7) | 68 (42.2) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 369 (90.7) | 225 (91.5) | 144 (89.4) | 0.58 | |

| African American | 14 (3.4) | 9 (3.7) | 5 (3.1) | ||

| Hispanic | 6 (1.5) | 4 (1.6) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Asian | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Indian American | 12 (2.9) | 5 (2.0) | 7 (4.3) | ||

| Native American | 5 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.9) | ||

| Race (grouped into 2 categories) | |||||

| White | 369 (90.7) | 225 (91.5) | 144 (89.4) | 0.49 | |

| Other | 38 (9.3) | 21 (8.5) | 17 (10.6) | ||

| Education | |||||

| High school, equivalent or less | 173 (43.5) | 98 (40.5) | 75 (48.1) | 0.14 | |

| Some post-high-school education and above | 225 (56.1) | 144 (59.5) | 81 (51.9) | ||

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 77 (20.3) | 47 (20.2) | 30 (20.4) | 0.01 * | |

| Not employed | 44 (11.6) | 18 (7.7) | 26 (17.7) | ||

| Not in labor force | 259 (68.1) | 168 (72.1) | 91 (61.9) | ||

| Household income in the last 12 months | |||||

| ≤$20,000 | 127 (33.1) | 52 (23.3) | 75 (50.3) | <0.0001 * | |

| $21,000–$35,000 | 129 (34.7) | 80 (35.9) | 49 (32.9) | ||

| >$35,000 | 116 (31.2) | 91 (40.8) | 25 (16.8) | ||

| Number of adults | |||||

| 1 | 94 (23.0) | 58 (23.3) | 36 (22.5) | <0.0001 * | |

| 2 | 226 (55.2) | 157 (63.1) | 69 (43.1) | ||

| ≥3 | 89 (21.8) | 34 (13.6) | 55 (34.4) | ||

| Number of children | |||||

| 0 | 318 (78.1) | 214 (86.3) | 104 (65.4) | <0.0001 * | |

| ≥1 | 89 (21.9) | 34 (13.7) | 55 (34.6) | ||

| Stable housing over the past 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 384 (93.9) | 243 (97.6) | 141 (88.1) | 0.0001 * | |

| No | 26 (6.1) | 6 (2.4) | 19 (11.9) | ||

| Military status | |||||

| Veteran | 351 (91.6) | 215 (91.9) | 136 (91.3) | 0.83 | |

| Active/non-active | 32 (8.2) | 19 (8.1) | 13 (8.7) | ||

| Military Branch | |||||

| Air Force | 63 (15.4) | 50 (20.1) | 13 (8.1) | 0.01 * | |

| Army | 220 (53.7) | 121 (48.6) | 99 (61.5) | ||

| Coast Guard | 3 (0.7) | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Marine Corps | 41 (10.0) | 24 (9.6) | 17 (10.5) | ||

| Navy | 75 (18.3) | 46 (18.5) | 29 (18.0) | ||

| Multiple branches | 8 (1.9) | 5 (2.0) | 3 (1.9) | ||

| Guard/Reserve | |||||

| Yes | 154 (41.5) | 97 (40.9) | 57 (42.5) | 0.76 | |

| No | 217 (58.5) | 140 (59.1) | 77 (57.5) | ||

| Years of service | |||||

| 1–10 years | 318 (81.1) | 189 (79.1) | 129 (84.3) | 0.34 | |

| 11–20 years | 42 (10.7) | 27 (11.3) | 15 (9.8) | ||

| 21–40 years | 32 (8.2) | 23 (9.6) | 9 (5.9) | ||

| Obesity | |||||

| Yes | 84 (31.0) | 46 (25.8) | 38 (40.9) | 0.03 * | |

| No | 187 (69.0) | 132 (74.2) | 55 (59.1) | ||

| Any of the following conditions: High blood pressure High cholesterol Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 233 (70.2) | 144 (68.9) | 89 (72.4) | 0.50 | |

| No | 99 (29.8) | 65 (31.1) | 34 (27.6) | ||

| Approved to receive Veterans Affairs healthcare | |||||

| Yes | 275 (71.4) | 175 (74.8) | 100 (66.2) | 0.07 | |

| No | 110 (28.6) | 59 (25.2) | 51 (33.8) | ||

| Service-related Veterans Affairs-recognized disability | |||||

| Yes | 158 (38.4) | 94 (37.9) | 64 (39.5) | 0.74 | |

| No | 252 (61.5) | 154 (62.1) | 98 (60.5) | ||

| Service-related disability not recognized by Veterans Affairs | |||||

| Yes | 103 (26.1) | 53 (22.1) | 50 (32.3) | 0.03 * | |

| No | 292 (73.9) | 187 (77.9) | 105 (67.7) | ||

| Depressive symptoms | |||||

| Yes | 68 (17.5) | 27 (11.5) | 41 (26.8) | 0.0001 * | |

| No | 320 (82.5) | 208 (88.5) | 112 (73.2) | ||

| Characteristics | N (%) | p-Value 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Food Secure | Food Insecure | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 352 (85.8) | 187 (89.9) | 165 (81.7) | 0.02 * | |

| Female | 58 (14.2) | 21 (10.1) | 37 (18.3) | ||

| Age | |||||

| 18–64 | 206 (50.1) | 78 (37.3) | 128 (63.4) | <0.0001 * | |

| ≥65 | 205 (49.9) | 131 (62.7) | 74 (36.6) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 263 (64.1) | 148 (70.8) | 115 (57.2) | 0.004 * | |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated/Never married | 147 (35.8) | 61 (29.2) | 86 (42.8) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 369 (90.7) | 186 (90.7) | 183 (90.6) | 0.56 | |

| African American | 14 (3.4) | 8 (3.9) | 6 (3.0) | ||

| Hispanic | 6 (1.5) | 4 (1.9) | 2 (1.0) | ||

| Asian | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Indian American | 12 (2.9) | 4 (1.9) | 8 (4.0) | ||

| Native American | 5 (1.2) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 369 (90.7) | 186 (90.7) | 183 (90.6) | 0.96 | |

| Other | 38 (9.3) | 19 (9.3) | 19 (9.4) | ||

| Education | |||||

| High school, equivalent or less | 173 (43.5) | 82 (40.6) | 91 (46.4) | 0.38 | |

| Some post-high-school education and above | 225 (56.5) | 120 (59.4) | 105 (53.6) | ||

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 77 (20.3) | 43 (21.7) | 34 (18.7) | 0.08 | |

| Not employed | 44 (11.6) | 16 (8.1) | 28 (15.4) | ||

| Not in labor force | 259 (68.1) | 139 (70.2) | 120 (65.9) | ||

| Household income in the last 12 months | |||||

| ≤$20,000 | 127 (34.1) | 37 (20.3) | 92 (47.4) | <0.0001 * | |

| $21,000–$35,000 | 129 (34.7) | 57 (31.3) | 75 (37.9) | ||

| >$35,000 | 116 (31.2) | 88 (48.3) | 31 (14.7) | ||

| Number of adults | |||||

| 1 | 94 (23.0) | 45 (21.6) | 49 (24.4) | 0.0002 * | |

| 2 | 226 (55.2) | 133 (63.9) | 93 (46.3) | ||

| ≥3 | 89 (21.8) | 30 (14.4) | 59 (29.3) | ||

| Number of children | |||||

| 0 | 318 (78.1) | 178 (85.6) | 140 (70.3) | 0.0002 * | |

| ≥1 | 89 (21.9) | 30 (14.4) | 59 (29.6) | ||

| Stable housing over the past 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 384 (93.9) | 203 (97.6) | 181 (90.1) | 0.001 * | |

| No | 25 (6.1) | 5 (2.4) | 20 (9.9) | ||

| Military status | |||||

| Veteran | 351 (91.6) | 178 (91.7) | 173 (91.5) | 0.94 | |

| Active/Non-active | 32 (8.4) | 16 (8.2) | 16 (8.5) | ||

| Military Branch | |||||

| Air Force | 63 (15.4) | 46 (22.0) | 17 (8.5) | 0.02 * | |

| Army | 220 (53.7) | 100 (47.8) | 120 (59.7) | ||

| Coast Guard | 3 (0.7) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Marine Corps | 41 (10.0) | 20 (9.6) | 21 (10.4) | ||

| Navy | 75 (18.3) | 38 (18.2) | 37 (18.4) | ||

| Multiple branches | 8 (1.9) | 3 (1.4) | 5 (2.5) | ||

| Guard/Reserve | |||||

| Yes | 154 (41.5) | 88 (44.0) | 66 (38.6) | 0.29 | |

| No | 217 (58.5) | 112 (56.0) | 105 (61.4) | ||

| Years of service | |||||

| 1–10 | 318 (81.1) | 153 (76.5) | 165 (85.9) | 0.05 * | |

| 11–20 | 42 (10.7) | 26 (13.0) | 16 (8.3) | ||

| 21–40 | 32 (8.2) | 21 (10.5) | 11 (5.7) | ||

| Obesity | |||||

| Yes | 84 (31.0) | 34 (23.3) | 50 (40) | 0.003 * | |

| No | 187 (69.0) | 112 (76.7) | 75 (60.0) | ||

| Any of the following conditions: High blood pressure High cholesterol Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 233 (70.2) | 123 (69.5) | 110 (71.0) | 0.77 | |

| No | 99 (29.8) | 54 (30.5) | 45 (29.0) | ||

| Approved to receive Veterans Affairs healthcare | |||||

| Yes | 275 (71.4) | 141 (72.7) | 134 (70.2) | 0.58 | |

| No | 110 (28.5) | 53 (27.3) | 57 (29.8) | ||

| Service-related Veterans Affairs-recognized disability | |||||

| Yes | 158 (38.4) | 80 (38.6) | 78 (38.4) | 0.96 | |

| No | 22 (61.5) | 127 (61.3) | 125 (61.6) | ||

| Service-related disability not recognized by Veterans Affairs | |||||

| Yes | 103 (26.1) | 40 (19.9) | 63 (32.5) | 0.004 * | |

| No | 292 (73.9) | 161 (80.1) | 131 (67.5) | ||

| Depressive symptoms | |||||

| Yes | 68 (17.5) | 20 (10.1) | 48 (25.1) | <0.0001 * | |

| No | 320 (82.5) | 177 (89.8) | 143 (74.9) | ||

| Outcome | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day food security model | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | Yes | 2.28 | 0.3 | 0.02 * |

| Enrollment in 1 or more VA benefits | Yes | 0.60 | 0.3 | 0.07 |

| Receiving income from any of these programs: VA veterans’ pension, Payments from an employer pension, Withdrawals from a retirement fund, Social Security Income | Yes | 2.27 | 0.4 | 0.03 * |

| Receiving income from any of these programs: TANF, Unemployment compensation, General Assistance, or Assistance from the Township Trustee | Yes | 3.92 | 0.5 | 0.01 * |

| Enrollment in SNAP | Yes | 1.58 | 0.3 | 0.15 |

| Enrollment in any of these programs: free meals (e.g., “Meals on Wheels”, senior center, soup kitchen), Women, Infants, and Children program (WIC), free or reduced-price meals at school or childcare | Yes | 0.78 | 0.4 | 0.50 |

| 12-month food security model | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | Yes | 2.34 | 0.4 | 0.02 * |

| Enrollment in 1 or more VA benefits | Yes | 0.55 | 0.3 | 0.03 * |

| Receiving income from any of these programs: VA veterans’ pension, Payments from an employer pension, Withdrawals from a retirement fund, Social Security Income | Yes | 2.51 | 0.3 | 0.01 * |

| Receiving income from any of these programs: TANF, Unemployment compensation, General Assistance, or Assistance from the Township Trustee | Yes | 3.09 | 0.5 | 0.04 * |

| Enrollment in SNAP | Yes | 1.30 | 0.3 | 0.41 |

| Enrollment in any of these programs: free meals (e.g., “Meals on Wheels”, senior center, soup kitchen), Women, Infants, and Children program (WIC), free or reduced-price meals at school or childcare | Yes | 0.70 | 0.4 | 0.34 |

| Outcome | β Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day food security | |||

| Social isolation | 7.2 | 1.2 | <0.0001 * |

| 12-month food security | |||

| Social isolation | 6.0 | 1.1 | <0.0001 * |

| Outcome | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model controlling for 30-day food security | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | Yes | 1.13 | 0.02 | <0.0001 * |

| Receiving income from any of these programs: VA veterans pension, Payments from an employer pension, Withdrawals from a retirement fund, Social Security Income | Yes | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| Receiving income from any of these programs: TANF, Unemployment compensation, General Assistance, or Assistance from the Township Trustee | Yes | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.33 |

| Model controlling for 12-month food security | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | Yes | 1.12 | 0.02 | <0.0001 * |

| Enrollment in 1 or more VA benefits | Yes | 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.62 |

| Receiving income from any of these programs: VA veterans pension, Payments from an employer pension, Withdrawals from a retirement fund, Social Security Income | Yes | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| Receiving income from any of these programs: TANF, Unemployment compensation, General Assistance, or Assistance from the Township Trustee | Yes | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| Outcome | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day food security | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | Yes | 0.92 | 0.40 | 0.85 |

| 12-month food security | ||||

| Depression | Yes | 1.06 | 0.41 | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uwashimimana, M.A.; MacDermid Wadsworth, S.; Sneddon, D.A.; Newton, J.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. A Cross-Sectional Study Exploring the Role of Social Isolation in the Relationship Between Food Insecurity, Depressive Symptoms, and Resource Use Among Midwestern Rural Veterans in the U.S. Nutrients 2025, 17, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020318

Uwashimimana MA, MacDermid Wadsworth S, Sneddon DA, Newton J, Eicher-Miller HA. A Cross-Sectional Study Exploring the Role of Social Isolation in the Relationship Between Food Insecurity, Depressive Symptoms, and Resource Use Among Midwestern Rural Veterans in the U.S. Nutrients. 2025; 17(2):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020318

Chicago/Turabian StyleUwashimimana, Mwiza A., Shelley MacDermid Wadsworth, Douglas A. Sneddon, Jake Newton, and Heather A. Eicher-Miller. 2025. "A Cross-Sectional Study Exploring the Role of Social Isolation in the Relationship Between Food Insecurity, Depressive Symptoms, and Resource Use Among Midwestern Rural Veterans in the U.S." Nutrients 17, no. 2: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020318

APA StyleUwashimimana, M. A., MacDermid Wadsworth, S., Sneddon, D. A., Newton, J., & Eicher-Miller, H. A. (2025). A Cross-Sectional Study Exploring the Role of Social Isolation in the Relationship Between Food Insecurity, Depressive Symptoms, and Resource Use Among Midwestern Rural Veterans in the U.S. Nutrients, 17(2), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020318