Patterns and Correlates of Bone Mineral Density Parameters Measured Using Calcaneus Quantitative Ultrasound in Chinese Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Calcaneus QUS Scan

2.3. Questionnaire Survey and Other Data Collection

2.4. Follow-Up and Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analyses

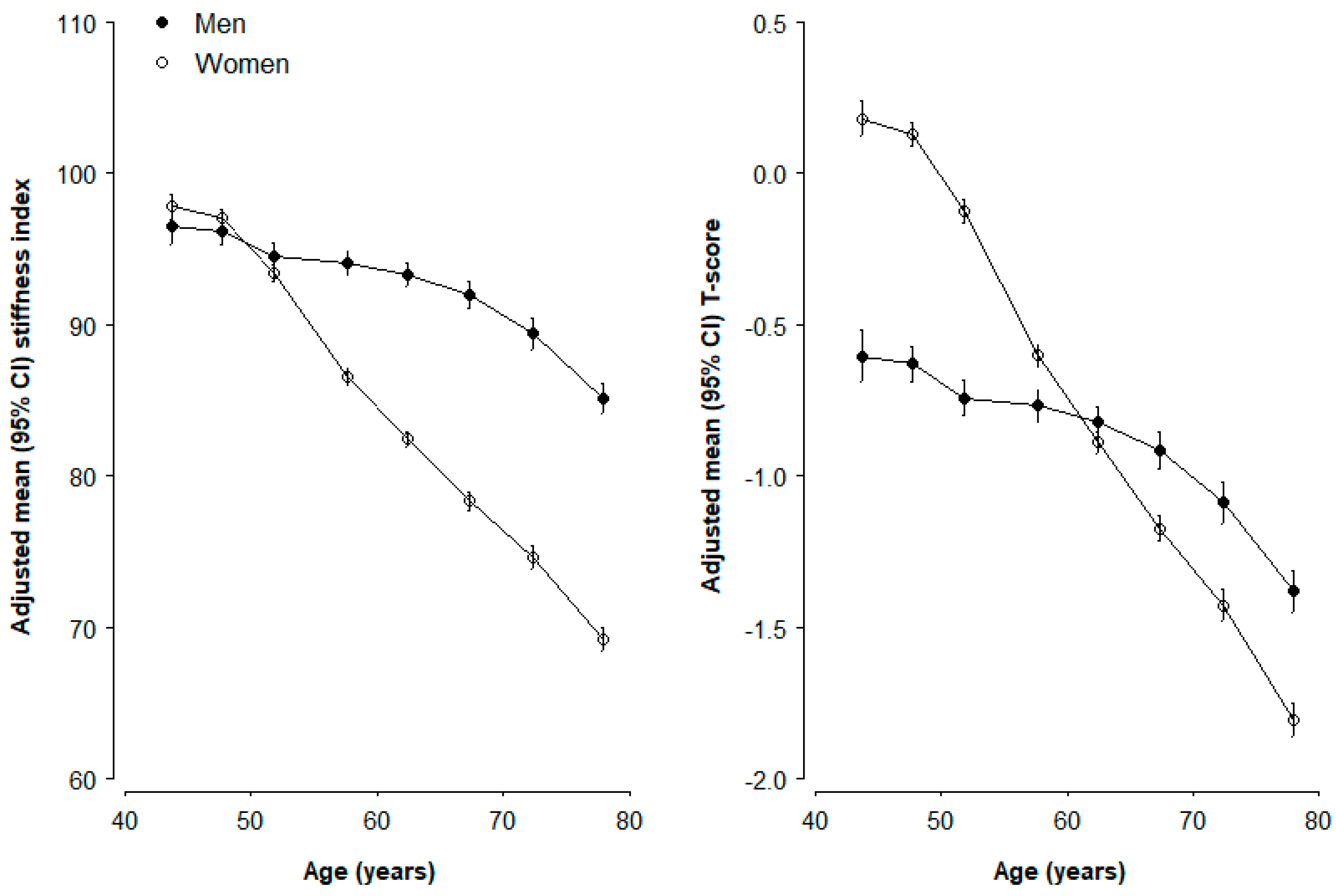

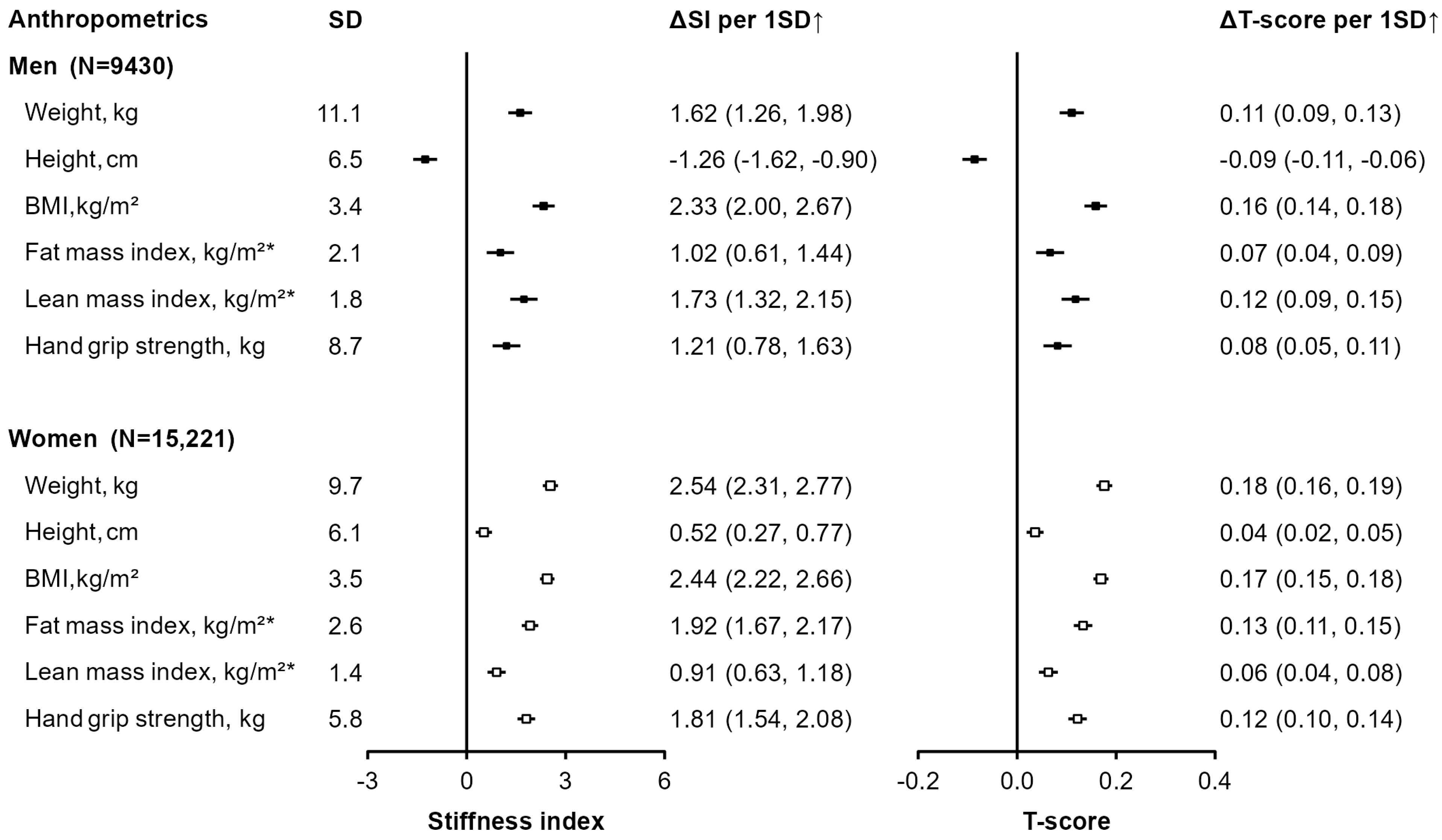

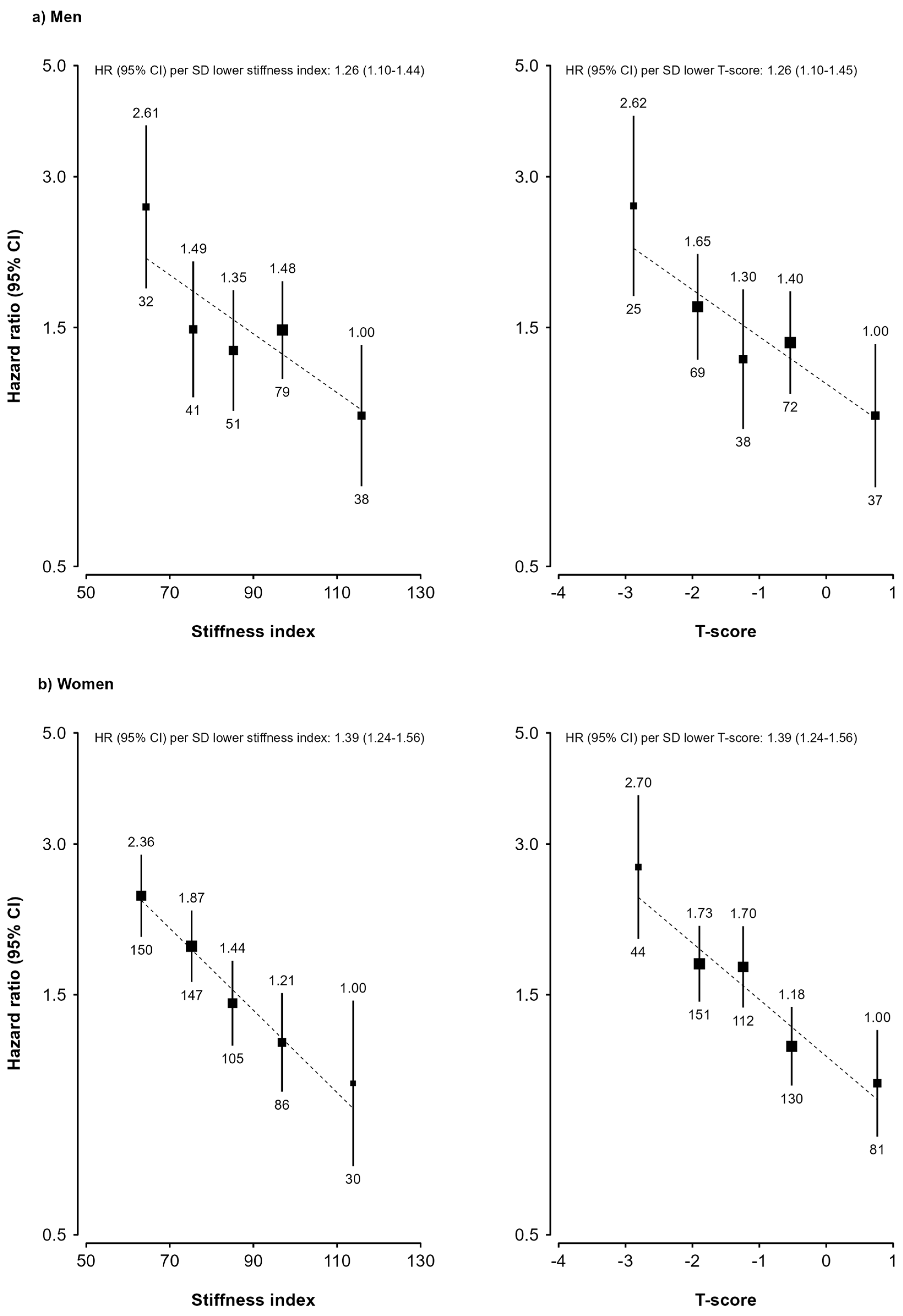

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borrelli, J. Taking control: The osteoporosis epidemic. Injury 2012, 43, 1235–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF). Factsheet About Osteoporosis. Available online: https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/sites/iofbonehealth/files/2019-06/AboutOsteoporosis_FactSheet_English.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Collaborators, G.B.D.F. Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e580–e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choksi, P.; Jepsen, K.J.; Clines, G.A. The challenges of diagnosing osteoporosis and the limitations of currently available tools. Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, P.; Renna, M.D.; Conversano, F.; Casciaro, E.; Muratore, M.; Quarta, E.; Paola, M.D.; Casciaro, S. Screening and early diagnosis of osteoporosis through X-ray and ultrasound based techniques. World J. Radiol. 2013, 5, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimpou, P.; Bosaeus, I.; Bengtsson, B.A.; Landin-Wilhelmsen, K. High correlation between quantitative ultrasound and DXA during 7 years of follow-up. Eur. J. Radiol. 2010, 73, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobio-Prieto, I.; Blanco-Diaz, M.; Pinero-Pinto, E.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, A.M.; Ruiz-Dorantes, F.J.; Albornoz-Cabello, M. Quantitative Ultrasound and Bone Health in Elderly People, a Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lee, L.; Chen, J.; Collins, R.; Wu, F.; Guo, Y.; Linksted, P.; Peto, R. Cohort profile: The Kadoorie Study of Chronic Disease in China (KSCDC). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qiao, Y.; Yu, C.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Z.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Yan, S.; Xie, X.; Huang, D.; et al. Tea consumption and bone health in Chinese adults: A population-based study. Osteoporos. Int. 2019, 30, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, A.; Diamond, T. Bone mineral density: Testing for osteoporosis. Aust. Prescr. 2016, 39, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, B.; Gong, J.; Xu, H.; Bai, Z. The correlation between calcaneus stiffness index calculated by QUS and total body BMD assessed by DXA in Chinese children and adolescents. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2014, 32, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Electric Company. Achilles EXPII: Affordable and Convenient Fracture Risk Assessment Using Quantitative Ultrasound. Available online: https://medford.pro/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Brochure-Achilles-EXPII-QUS-from-GE-Healthcare-JB52895XX.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Collins, R.; Guo, Y.; Peto, R.; Wu, F.; Li, L.; China Kadoorie Biobank collaborative, g. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: Survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 1652–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadji, P.; Hars, O.; Wuster, C.; Bock, K.; Alberts, U.S.; Bohnet, H.G.; Emons, G.; Schulz, K.D. Stiffness index identifies patients with osteoporotic fractures better than ultrasound velocity or attenuation alone. Maturitas 1999, 31, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Li, L.; Whitlock, G.; Bennett, D.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Z.; Chen, J.; Sherliker, P.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, N.; et al. Patterns and socio-demographic correlates of domain-specific physical activities and their associations with adiposity in the China Kadoorie Biobank study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragg, F.; Tang, K.; Guo, Y.; Iona, A.; Du, H.; Holmes, M.V.; Bian, Z.; Kartsonaki, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; et al. Associations of General and Central Adiposity With Incident Diabetes in Chinese Men and Women. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNicholl, T.; Curtis, L.; Dubin, J.A.; Mourtzakis, M.; Nasser, R.; Laporte, M.; Keller, H. Handgrip strength predicts length of stay and quality of life in and out of hospital. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2501–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Parish, S.; Bennett, D.A.; Du, H.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhou, G.; Lv, J.; et al. Gender differences in modifiable risk factors for hip fracture: 10-year follow-up of a prospective study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 291, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J.P.; Morris, J.A.; Medina-Gomez, C.; Forgetta, V.; Warrington, N.M.; Youlten, S.E.; Zheng, J.; Gregson, C.L.; Grundberg, E.; Trajanoska, K.; et al. Identification of 153 new loci associated with heel bone mineral density and functional involvement of GPC6 in osteoporosis. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, D.F.; Peto, J.; Babiker, A.G. Floating absolute risk: An alternative to relative risk in survival and case-control analysis avoiding an arbitrary reference group. Stat. Med. 1991, 10, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looker, A.C.; Melton, L.J., 3rd; Harris, T.; Borrud, L.; Shepherd, J.; McGowan, J. Age, gender, and race/ethnic differences in total body and subregional bone density. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.C.; Todd, J.M.; Schollum, L.M.; Kuhn-Sherlock, B.; McLean, D.W.; Wylie, K. Bone health comparison in seven Asian countries using calcaneal ultrasound. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimai, H.P. Use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for diagnosis and fracture risk assessment; WHO-criteria, T- and Z-score, and reference databases. Bone 2017, 104, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, N.; Adler, R.; Bilezikian, J.P. Osteoporosis diagnosis in men: The T-score controversy revisited. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2014, 12, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hologic, I. Sahara Clinical Bone Sonometer User Guide; Hologic, Inc.: Waltham, MA USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hans, D.; Dargent-Molina, P.; Schott, A.M.; Sebert, J.L.; Cormier, C.; Kotzki, P.O.; Delmas, P.D.; Pouilles, J.M.; Breart, G.; Meunier, P.J. Ultrasonographic heel measurements to predict hip fracture in elderly women: The EPIDOS prospective study. Lancet 1996, 348, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, S.; Sone, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Yoshimura, N.; Nakatsuka, K.; Masunari, N.; Fujita, S.; Kushida, K.; Fukunaga, M. Heel bone ultrasound predicts non-spine fracture in Japanese men and women. Osteoporos. Int. 2005, 16, 2107–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloskey, E.V.; Kanis, J.A.; Oden, A.; Harvey, N.C.; Bauer, D.; Gonzalez-Macias, J.; Hans, D.; Kaptoge, S.; Krieg, M.A.; Kwok, T.; et al. Predictive ability of heel quantitative ultrasound for incident fractures: An individual-level meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2015, 26, 1979–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bashaireh, A.M.; Haddad, L.G.; Weaver, M.; Chengguo, X.; Kelly, D.L.; Yoon, S. The Effect of Tobacco Smoking on Bone Mass: An Overview of Pathophysiologic Mechanisms. J. Osteoporos. 2018, 2018, 1206235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Choi, S.; Kim, K.; Lee, G.; Park, S.M. Association between alcohol consumption and bone mineral density in elderly Korean men and women. Arch. Osteoporos. 2018, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.D.; Hong, J.Y.; Han, K.; Lee, J.C.; Shin, B.J.; Choi, S.W.; Suh, S.W.; Yang, J.H.; Park, S.Y.; Bang, C. Relationship between bone mineral density and alcohol intake: A nationwide health survey analysis of postmenopausal women. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.Y.; Ho, A.Y.; Lam, K.F.; Tam, S.; Kung, A.W. Determinants of bone mineral density in Chinese men. Osteoporos. Int. 2005, 16, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Shen, Y.M.; Li, S.B.; Huang, S.W.; Kuo, Y.J.; Chen, Y.P. Association of Coffee and Tea Intake with Bone Mineral Density and Hip Fracture: A Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2023, 59, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Lin, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ru, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, S. Drinking tea before menopause is associated with higher bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdi Kara, I.; Aydin, S.; Gemalmaz, A.; Akturk, Z.; Yaman, H.; Bozdemir, N.; Kurdak, H.; Sitmapinar, K.; Devran Sencar, I.; Basak, O.; et al. Habitual tea drinking and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Turkish women: Investigation of prevalence of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Turkey (IPPOT Study). Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2007, 77, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, L.A.; Ward, W.E. Tea and bone health: Findings from human studies, potential mechanisms, and identification of knowledge gaps. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1603–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.M.; Gordon, C.M.; Janz, K.F.; Kalkwarf, H.J.; Lappe, J.M.; Lewis, R.; O’Karma, M.; Wallace, T.C.; Zemel, B.S. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: A systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 1281–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Du, H.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Z.; Yu, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Han, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Coarse Grain Consumption and Risk of Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Prospective Cohort Study of Chinese Adults. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.H. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 517S–520S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Sung, J.; Joung, H. A fruit, milk and whole grain dietary pattern is positively associated with bone mineral density in Korean healthy adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Karamati, M.; Shariati-Bafghi, S.E.; Rashidkhani, B. Increased inflammatory potential of diet is associated with bone mineral density among postmenopausal women in Iran. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Cao, W.T.; Tian, H.Y.; He, J.; Chen, G.D.; Chen, Y.M. Greater Intake of Fruit and Vegetables Is Associated with Greater Bone Mineral Density and Lower Osteoporosis Risk in Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, P. The role of low acid load in vegetarian diet on bone health: A narrative review. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2016, 146, w14277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Shao, R.; Wang, H.; Miao, J.; Wang, X. Dietary vitamin A, C, and E intake and subsequent fracture risk at various sites: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine 2020, 99, e20841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.F.; Luo, M.H.; Liang, G.H.; Yang, W.Y.; Xiao, X.; Wei, X.; Yu, J.; Guo, D.; Chen, H.Y.; Pan, J.K.; et al. Can Dietary Intake of Vitamin C-Oriented Foods Reduce the Risk of Osteoporosis, Fracture, and BMD Loss? Systematic Review With Meta-Analyses of Recent Studies. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.; Park, K. Association between Phytochemical Index and Osteoporosis in Women: A Prospective Cohort Study in Korea. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Marzorati, M.; Spence, L.; Weaver, C.M.; Williamson, P.S. New Frontiers in Fibers: Innovative and Emerging Research on the Gut Microbiome and Bone Health. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017, 36, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.M.; Park, J.; Han, S.; Jang, H.D.; Hong, J.Y.; Han, K.; Kim, H.J.; Yeom, J.S. Underweight and risk of fractures in adults over 40 years using the nationwide claims database. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Pham, L.T.; Nguyen, N.D.; Lai, T.Q.; Nguyen, T.V. Contributions of lean mass and fat mass to bone mineral density: A study in postmenopausal women. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2010, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, C.G.; Halse, J.I.; Eide, G.E.; Brun, J.G.; Tell, G.S. Impact of lean mass and fat mass on bone mineral density: The Hordaland Health Study. Maturitas 2008, 59, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, M.E.; Shi, L.; Gona, P.N.; Troped, P.J.; Camhi, S.M. Age, Sex, and Race/Ethnicity Associations between Fat Mass and Lean Mass with Bone Mineral Density: NHANES Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, H.; Brennan, S.L.; Nicholson, G.C.; Kotowicz, M.A.; Henry, M.J.; Pasco, J.A. Calcaneal ultrasound reference ranges for Australian men and women: The Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, S.; Meng, X.; Li, W.; Deng, Y.; Li, N.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, M.; Leng, J. The impact of height on low/reduced bone mineral density in Chinese adolescents aged 12–14 years old: Gender differences. Arch. Osteoporos. 2019, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, H.; Iki, M.; Morita, A.; Ikeda, Y. Effects of pubertal development, height, weight, and grip strength on the bone mineral density of the lumbar spine and hip in peripubertal Japanese children: Kyoto kids increase density in the skeleton study (Kyoto KIDS study). J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2005, 23, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Li, C.; Pan, J.; Zhang, S.; Dong, H.; Wu, Y.; Lv, J. Causal Associations of Anthropometric Measurements With Fracture Risk and Bone Mineral Density: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2021, 36, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yland, J.J.; Wesselink, A.K.; Lash, T.L.; Fox, M.P. Misconceptions About the Direction of Bias From Nondifferential Misclassification. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 191, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Men (n = 9430) | Women (n = 15,221) | Overall (n = 24,651) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.2 (10.3) | 59.0 (10.0) | 59.5 (10.1) |

| Urban, % | 43.3 | 42.9 | 43.1 |

| Education > 6 years, % | 57.5 | 41.6 | 47.7 |

| Annual household income ≥75,000 yuan | 28.0 | 23.7 | 25.3 |

| Current smoking, % | 50.9 | 1.6 | 20.5 |

| Current alcohol drinking, % | 28.6 | 1.9 | 12.1 |

| Regular tea drinking, % * | 46.2 | 17.6 | 28.6 |

| Physical activity, MET-hours/day | 19.0 (15.2) | 17.6 (12.7) | 18.1 (13.7) |

| Regular dietary consumption, % † | |||

| Fresh fruit | 39.0 | 48.7 | 45.0 |

| Coarse grain | 19.2 | 19.1 | 19.1 |

| Milk | 10.5 | 11.5 | 11.1 |

| Red meat | 60.4 | 52.4 | 55.5 |

| Fish and shellfish | 11.5 | 9.5 | 10.3 |

| Eggs | 41.4 | 38.1 | 39.4 |

| Menopause, % | - | 76.9 | - |

| Menopause age, years | - | 48.8 (4.5) | - |

| Supplement intake, % | |||

| Calcium, iron, and zinc | 14.5 | 21.6 | 18.9 |

| Fish oil and cod fish oil | 7.0 | 9.8 | 8.7 |

| Multi-vitamins | 6.4 | 8.9 | 8.0 |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, ng/mL ‡ | 37.3 (10.3) | 31.2 (8.5) | 33.9 (9.8) |

| Body composition measures | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.0 (3.4) | 24.3 (3.5) | 24.2 (3.5) |

| Standing height, cm | 164.7 (6.5) | 153.5 (6.1) | 157.8 (8.3) |

| Body weight, kg | 65.2 (11.2) | 57.4 (9.7) | 60.4 (11.0) |

| Fat body mass, kg § | 13.4 (5.9) | 18.1 (6.5) | 16.3 (6.7) |

| Fat mass index, kg/m2 § | 4.9 (2.1) | 7.6 (2.6) | 6.6 (2.8) |

| Lean body mass, kg § | 51.9 (6.9) | 39.3 (4.4) | 44.1 (8.2) |

| Lean mass index, kg/m2 § | 19.1 (1.8) | 16.7 (1.4) | 17.6 (2.0) |

| Hand grip strength, kg ¶ | 32.2 (8.7) | 20.1 (5.8) | 24.7 (9.2) |

| QUS parameters | |||

| BUA, dB/MHz | 113.3 (11.4) | 107.5 (12.4) | 109.7 (12.4) |

| SOS, m/s | 1562.2 (37.2) | 1551.6 (35.9) | 1555.6 (36.8) |

| Stiffness index (SI) | 92.8 (16.2) | 86.0 (16.2) | 88.6 (16.6) |

| T-score | −0.85 (1.11) | −0.64 (1.13) | −0.72 (1.12) |

| eBMD, g/cm2 | 0.66 (0.12) | 0.62 (0.11) | 0.64 (0.12) |

| Men (N = 9430) | Women (N = 15,221) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Stiffness Index | T-Score | N | Stiffness Index | T-Score | |

| Education | ||||||

| No formal education | 853 | 92.0 (90.8, 93.1) | −0.91 (−0.99, −0.84) | 4107 | 85.7 (85.2, 86.1) | −0.66 (−0.70, −0.63) |

| Primary school | 3157 | 93.5 (92.9, 94.1) | −0.81 (−0.85, −0.77) | 4782 | 86.0 (85.6, 86.4) | −0.64 (−0.67, −0.61) |

| >6 years | 5420 | 92.5 (92.1, 93.0) | −0.87 (−0.91, −0.84) | 6332 | 86.2 (85.8, 86.6) | −0.63 (−0.65, −0.60) |

| Ptrend | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.14 | 0.15 | ||

| Annual household income, yuan/year | ||||||

| <35,000 | 3515 | 92.2 (91.6, 92.8) | −0.90 (−0.94, −0.86) | 6406 | 86.2 (85.8, 86.5) | −0.63 (−0.65, −0.60) |

| 35,000–74,999 | 3270 | 93.2 (92.6, 93.7) | −0.83 (−0.87, −0.79) | 5212 | 86.1 (85.8, 86.5) | −0.63 (−0.66, −0.60) |

| ≥75,000 | 2645 | 93.2 (92.5, 93.8) | −0.83 (−0.88, −0.79) | 3603 | 85.4 (84.9, 85.9) | −0.68 (−0.71, −0.64) |

| Ptrend | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never regular | 3136 | 93.9 (93.3, 94.4) | −0.78 (−0.82, −0.74) | 14,890 | 86.0 (85.8, 86.2) | −0.64 (−0.65, −0.62) |

| Ex-regular | 1491 | 93.7 (92.9, 94.5) | −0.79 (−0.85, −0.74) | 93 | 85.4 (82.6, 88.2) | −0.69 (−0.88, −0.50) |

| Current regular | 4803 | 91.8 (91.4, 92.3) | −0.92 (−0.95, −0.89) | 238 | 84.8 (83.1, 86.6) | −0.72 (−0.85, −0.60) |

| Ptrend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.16 | ||

| Alcohol drinking | ||||||

| Never regular | 5775 | 92.7 (92.3, 93.1) | −0.86 (−0.89, −0.84) | 14,738 | 86.0 (85.8, 86.2) | −0.64 (−0.65, −0.62) |

| Ex-regular | 961 | 93.0 (91.9, 94.0) | −0.85 (−0.91, −0.78) | 192 | 85.4 (83.5, 87.3) | −0.68 (−0.82, −0.55) |

| Current regular | 2694 | 93.1 (92.4, 93.7) | −0.84 (−0.88, −0.80) | 291 | 85.4 (83.9, 87.0) | −0.68 (−0.79, −0.57) |

| Ptrend | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.37 | ||

| Tea drinking | ||||||

| Never | 3191 | 92.3 (91.7, 92.9) | −0.89 (−0.93, −0.85) | 9398 | 85.6 (85.4, 85.9) | −0.66 (−0.68, −0.64) |

| Occasional | 1878 | 93.1 (92.3, 93.8) | −0.84 (−0.89, −0.79) | 3143 | 86.3 (85.8, 86.8) | −0.62 (−0.65, −0.58) |

| Regular | 4361 | 93.1 (92.6, 93.6) | −0.83 (−0.87, −0.80) | 2680 | 86.8 (86.2, 87.3) | −0.59 (−0.62, −0.55) |

| Ptrend | 0.06 | 0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Physical activity † | ||||||

| 1st tertile | 3108 | 91.8 (91.3, 92.4) | −0.92 (−0.96, −0.88) | 5072 | 85.2 (84.8, 85.6) | −0.69 (−0.72, −0.67) |

| 2nd tertile | 3180 | 92.9 (92.4, 93.5) | −0.85 (−0.89, −0.81) | 5076 | 86.2 (85.8, 86.6) | −0.63 (−0.65, −0.60) |

| 3rd tertile | 3142 | 93.7 (93.1, 94.3) | −0.80 (−0.84, −0.76) | 5073 | 86.5 (86.1, 86.9) | −0.60 (−0.63, −0.58) |

| Ptrend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Dietary Consumption | ||||||

| Fresh fruit | ||||||

| Less than weekly | 2483 | 92.0 (91.3, 92.6) | −0.91 (−0.95, −0.87) | 3043 | 85.4 (84.9, 85.9) | −0.68 (−0.71, −0.64) |

| Weekly | 4231 | 93.2 (92.7, 93.6) | −0.83 (−0.87, −0.80) | 6454 | 86.0 (85.7, 86.4) | −0.64 (−0.66, −0.61) |

| Daily | 2716 | 93.0 (92.4, 93.7) | −0.84 (−0.88, −0.80) | 5724 | 86.2 (85.9, 86.6) | −0.62 (−0.65, −0.60) |

| Ptrend | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| Coarse grain | ||||||

| Never/rarely | 3955 | 92.3 (91.8, 92.9) | −0.89 (−0.93, −0.85) | 5614 | 85.6 (85.2, 86.0) | −0.67 (−0.70, −0.64) |

| Monthly | 1991 | 92.5 (91.8, 93.2) | −0.87 (−0.92, −0.83) | 3483 | 86.0 (85.5, 86.5) | −0.64 (−0.67, −0.61) |

| At least weekly | 3484 | 93.5 (92.9, 94.2) | −0.81 (−0.85, −0.76) | 6124 | 86.4 (86.0, 86.8) | −0.61 (−0.64, −0.59) |

| Ptrend | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| Milk | ||||||

| Never/rarely | 7073 | 92.7 (92.3, 93.1) | −0.86 (−0.89, −0.84) | 11,377 | 86.2 (86.0, 86.5) | −0.62 (−0.64, −0.61) |

| Monthly−3 days/week | 1368 | 93.3 (92.4, 94.1) | −0.82 (−0.88, −0.77) | 2096 | 85.5 (84.9, 86.1) | −0.67 (−0.71, −0.63) |

| >4 days/week | 989 | 93.1 (92.1, 94.2) | −0.83 (−0.90, −0.76) | 1748 | 85.0 (84.4, 85.7) | −0.71 (−0.75, −0.66) |

| Ptrend | 0.24 | 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, P.; Clarke, C.; Iona, A.; Wright, N.; Yao, P.; Chen, Y.; Schmidt, D.; Yang, L.; Sun, D.; Stevens, R.; et al. Patterns and Correlates of Bone Mineral Density Parameters Measured Using Calcaneus Quantitative Ultrasound in Chinese Adults. Nutrients 2025, 17, 865. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050865

Peng P, Clarke C, Iona A, Wright N, Yao P, Chen Y, Schmidt D, Yang L, Sun D, Stevens R, et al. Patterns and Correlates of Bone Mineral Density Parameters Measured Using Calcaneus Quantitative Ultrasound in Chinese Adults. Nutrients. 2025; 17(5):865. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050865

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Peng, Charlotte Clarke, Andri Iona, Neil Wright, Pang Yao, Yiping Chen, Dan Schmidt, Ling Yang, Dianjianyi Sun, Rebecca Stevens, and et al. 2025. "Patterns and Correlates of Bone Mineral Density Parameters Measured Using Calcaneus Quantitative Ultrasound in Chinese Adults" Nutrients 17, no. 5: 865. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050865

APA StylePeng, P., Clarke, C., Iona, A., Wright, N., Yao, P., Chen, Y., Schmidt, D., Yang, L., Sun, D., Stevens, R., Pei, P., Xu, X., Yu, C., Chen, J., Lv, J., Li, L., Chen, Z., & Du, H. (2025). Patterns and Correlates of Bone Mineral Density Parameters Measured Using Calcaneus Quantitative Ultrasound in Chinese Adults. Nutrients, 17(5), 865. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050865