Flavonoid Bioavailability and Attempts for Bioavailability Enhancement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

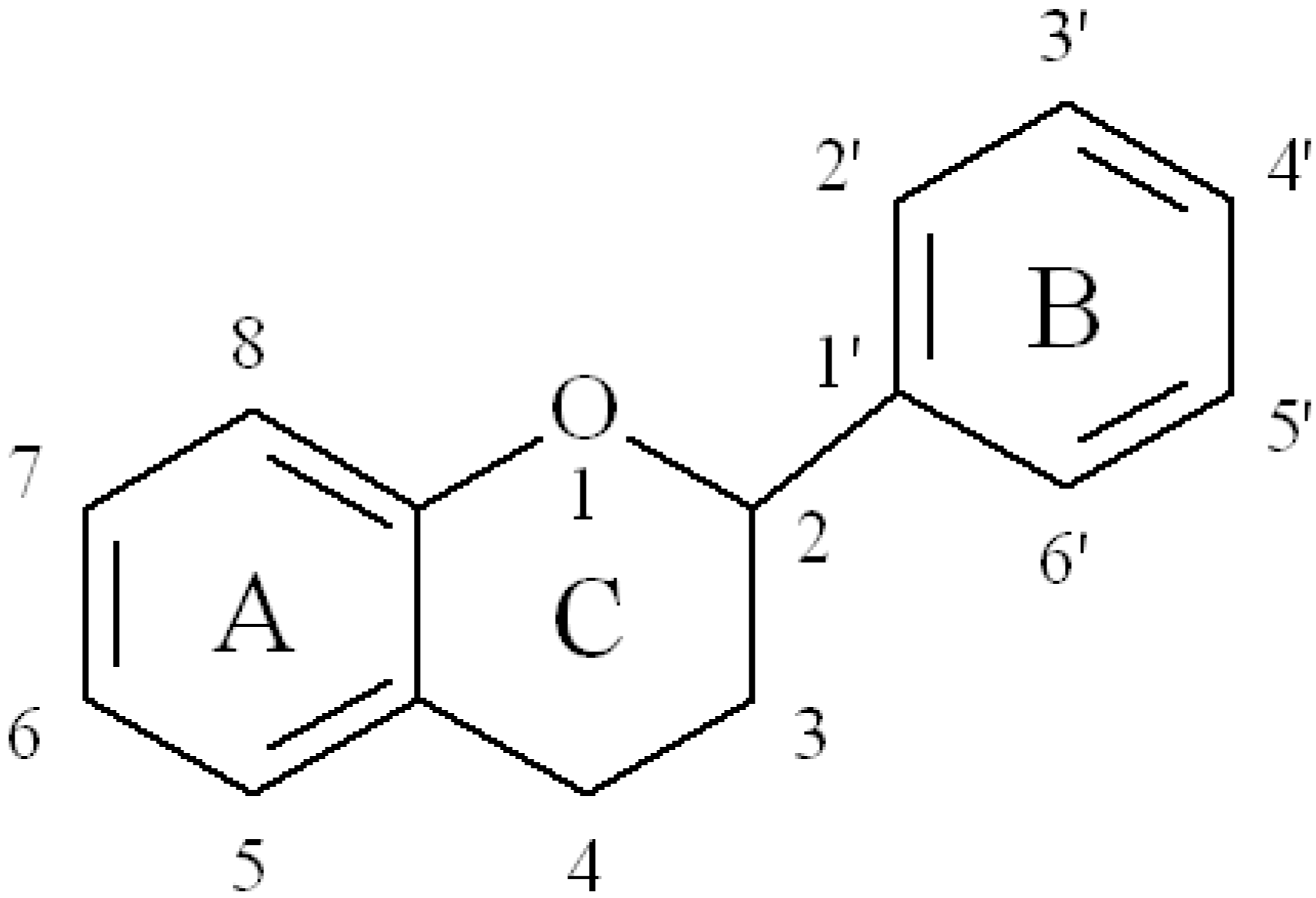

2. Flavonoids

| Flavonoid class (Common compounds) | Common food sources and amounts (mg/100 g edible portion) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavan-3-ols (i) (+)-Catechin, (ii) (−)-Epicatechin, (iii) Procyanidin B2 (dimer) an example; food values for all dimers present | Source | (i) [21] | (ii) [21] | (iii) [22] | ||

| Apples (Red Delicious, with skin) 1 | 2.00 | 9.83 | 15.12 | |||

|  | Apricots (raw) 1 | 3.67 | 4.74 | 1.33 | |

| Peaches (raw) 1 | 4.92 | 2.34 | 12.24 | |||

| Pears (raw) 1 | 0.27 | 3.76 | 2.73 | |||

| Strawberries (raw) 1 | 6.65 | 1.56 | 5.26 | |||

| (i) | (ii) | Black tea (brewed) 2 | 1.51 | 2.13 | 3.74 | |

| Blueberries (highbush, raw) 3 | 5.29 | 0.62 | 5.71 | ||

| Cranberries (raw) 3 | 0.39 | 4.37 | 25.93 | |||

| Cocoa (dry powder) 4 | 64.82 | 196.43 | 183.49 | |||

| Grapes (black/red) 5 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 2.38 | |||

| Red wine (table) 5 | 7.12 | 3.76 | 20.49 | |||

| (iii) | ||||||

| Flavonols (i) Kaempferol, (ii) Myricetin, (iii) Quercetin-3-O-glucoside an example of a glucoside, food values are for quercetin | Source [21] | (i) | (ii) | (iii) | ||

| Blueberries (highbush) 3 | 1.66 | 1.26 | 7.67 | |||

| Garlic 6 | 0.26 | 1.61 | 1.74 | |||

| Onions 6 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 21.40 | |||

| Kale 7 | 46.80 | 0.00 | 22.58 | |||

| Broccoli 7 | 7.84 | 0.06 | 3.26 | |||

| Spinach 8 | 15.75 | - | 5.75 | |||

| Black tea (brewed) 2 | 1.31 | 0.45 | 1.99 | |||

|  | Red wine 5 | 0.20 | 0.83 | 1.76 | |

| Cherry tomatoes 9 | 0.10 | - | 2.76 | |||

| Can be found ubiquitous in plant families. | ||||||

| (i) | (ii) | |||||

| ||||||

| (iii) | ||||||

| Anthocyanins (i) Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, (ii) Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, (iii) Malvidin-3-O-glucoside, (iv) Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside, Food values are for anthocyanidins (without the sugars) | Source [21] | (i) | (ii) | (iii) | (iv) | |

| Apples 1 | 1.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Blueberries (lowbush) 3 | 17.92 | 34.00 | 54.00 | 2.65 | ||

| Red wine 5 | 0.45 | 2.75 | 15.29 | - | ||

| Strawberries 1 | 1.63 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 25.69 | ||

|  | Usually in any pink to purple fruit or vegetable; except the Chenopodiaceae family (beets, quinoa, spinach, Swiss chard, etc.). | ||||

| (i) | (ii) | |||||

|  | |||||

| (iii) | (iv) | |||||

| Isoflavones (i) Daidzein, (ii) Genistein, (iii) Glycitein | Source [23] | (i) | (ii) | (iii) | ||

|  | Tofu (regular, raw) 10 | 8.56 | 12.99 | 1.98 | |

| Tempeh 10 | 22.66 | 36.15 | 3.82 | |||

| Soybean (raw, mature seeds, USA) 10 | 61.33 | 86.33 | 13.33 | |||

| (i) | (ii) | Peanuts (raw, all types) 10 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.26 | |

| Beans (common, raw) 10 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.00 | ||

| In the Fabaceae (legume) family especially the genus Glycine (soy), but also in small amounts in other plants. | ||||||

| (iii) | ||||||

| Flavanones (i) Eriodictyol, (ii) Hesperetin, (iii) Naringenin | Source [21] | (i) | (ii) | (iii) | ||

| Grapefruit (juice, white) 11 | 0.65 | 2.35 | 18.23 | |||

|  | Lemon (juice) 11 | 4.88 | 14.47 | 1.38 | |

| Orange (juice) 11 | 0.17 | 20.39 | 3.27 | |||

| Peppermint 13 | 30.92 | 9.52 | - | |||

| (i) | (ii) | |||||

| ||||||

| (iii) | ||||||

| Flavones (i) Apigenin, (ii) Luteolin | Source [21] | (i) | (ii) | |||

| Celery 13 | 2.85 | 1.05 | ||||

|  | Celery seed (spice) 13 | 83.70 | 811.41 | ||

| Parsley 13 | 215.46 | 1.09 | ||||

| Green peppers 9 | 0.00 | 4.71 | ||||

| Peppermint 12 | 8.71 | 11.33 | ||||

| (i) | (ii) | Common in leafy plants particularly Apiaceae family. | ||||

2.1. Flavan-3-ols

2.1.1. Monomeric Flavan-3-ols: Catechin and Epicatechin

2.1.2. Proanthocyanidins or Condensed Tannins

2.2. Flavonols

2.3. Anthocyanins

2.4. Isoflavones

2.5. Flavanones

2.6. Flavones

3. Bioavailability of Dietary Flavonoids

3.1. Metabolism and Bioavailability

3.2. Factors Affecting Bioavailability

3.2.1. Molecular Weight

3.2.2. Glycosylation

3.2.3. Metabolic Conversion

3.2.4. Interaction with Colonic Microflora

3.3. Efforts to Improve Bioavailability

3.3.1. Improving the Intestinal Absorption

| Flavonoid class | Molecular Weight | Glycosylation | Metabolic conversion | Colonic microflora |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Decreases bioavailability | Generally removed | Major factor in bioavailability; can take place in small intestine, liver and colon; usually to glucuronides but also sulphation and methylation [39]; facilitates urinary and biliary excretion [39]. | Influence availability; catabolize compounds to low molecular weight compounds that are readily absorbed [58]. |

| Flavan-3-ols (monomeric) | Major bioactive forms: conjugates of epicatechin [41]; catechin: methyl, sulfate and glucuronic acid conjugates; epicatechin: mainly to sulfate conjugates, no glucuronidation [41]. | |||

| Proanthocyanidins | Decreases bioavailability [40]. | Major bioactive forms: conjugates of epicatechin [41]; oligomeric procyanidins can absorb in small intestine [51]. | Influences polymeric proanthocyanidin degradation [50]. | |

| Flavonols | Sugars and their position affects bioavailability [44]. | Potentially active metabolites: glucuronides [44]. | Facilitates glucuronidation [60]. | |

| Anthocyanins | Anthocyanin derivatives (flavan-3-ol-anthocyanin dimer) can potentially be absorbed with less efficiency [47]. | Sometimes found with sugars intact in circulation [55]. | Major intestinal metabolites: glucuronide and sulfate conjugates of protocatechuic acid and phloroglucinaldehyde [46]; anthocyanin derivatives metabolically more resistant than parent compounds [47]. | |

| Isoflavones | Aglycone more bioavailable; possible deglycosylation prior hepatic metabolism [48]. | Metabolize daidzein to equol [58]. | ||

| Flavanones | Rapid absorption, low bioavailability [49]. | Extensive first-pass metabolism partly by intestinal bacteria degraded into phenolic compounds [49]. |

3.3.2. Changing the Site of Absorption

3.3.3. Improving the Metabolic Stability

3.3.4. Effect of the Food Matrix

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boeing, H.; Bechthold, A.; Bub, A. Critical review: Vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshipura, K.J.; Hu, F.B.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rimm, E.B.; Speizer, F.E.; Colditz, G.; Ascherio, A.; Rosner, B.; Spiegelman, D.; et al. The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 134, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, C.F.; Gago, B.; Barbosa, R.M.; de Freitas, V.; Laranjinha, J. LDL isolated from plasma-loaded red wine proanthocyanidins resist lipid oxidation and tocopherol depletion. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3798–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathna, S.H.; Wang, Y.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Ghanam, K. Apple peel flavonoid- and triterpene-enriched extracts differentially affect cholesterol homeostasis in hamsters. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 4, 963–971. [Google Scholar]

- Noll, C.; Hamelet, J.; Matulewicz, E.; Paul, J.L.; Delabar, J.M.; Janel, N. Effects of red wine polyphenolic compounds on paraoxonase-1 and lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 in hyperhomocysteinemic mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.J.; Dwyer, J.T.; Jacques, P.F.; McCullough, M.L. Associations between flavonoids and cardiovascular disease incidence or mortality in European and US populations. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beecher, G.R. Overview of dietary flavonoids: Nomenclature, occurrence and intake. J. Nutr. 2003, 3, 3248S–3254S. [Google Scholar]

- Somerset, S.M.; Johannot, L. Dietary flavonoid sources in Australian adults. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaki, N.; Kimira, M.; Katsumata, S.; Uehara, M.; Watanabe, S.; Suzuki, K. Distribution and major sources of flavonoid intakes in the middle-aged Japanese women. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2009, 44, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, C.; Cao, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X. Dietary flavonol and flavone intakes and their major food sources in Chinese adults. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Ros, R.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Berenguer, T.; Jakszyn, P.; Barricarte, A.; Ardanaz, E.; Amiano, P.; Dorronsoro, M.; Larrañaga, N.; et al. Estimation of dietary sources and flavonoid intake in a Spanish adult population (EPIC-Spain). J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Williamson, G.; Morand, C.; Scalbert, A.; Rémésy, C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 230S–242S. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, W.; Edwards, C.A.; Crozier, A. Absorption, excretion and metabolite profiling of methyl-, glucuronyl-, glucosyl- and sulpho-conjugates of quercetin in human plasma and urine after ingestion of onions. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Ronalds, C.M.; Rathgeber, B.; Robinson, R. Absorption and tissue distribution of dietary quercetin in broiler chickens. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathna, S.H.; Rupasinghe, H.P.; Needs, P.W. Apple peel bioactive rich extracts effectively inhibit in vitro human LDL cholesterol oxidation. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhao, X. Enhanced intestinal absorption of daidzein by borneol/menthol eutectic mixture and microemulsion. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2011, 12, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Gao, F.; Gao, Z.; Bu, H.; Gu, W.; Li, Y. A self-assembled nanodelivery system enhances the oral bioavailability of daidzein: In vitro characteristics and in vivo performance. Nanomedicine (London) 2011, 6, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, T. Methylation of dietary flavones greatly improves their hepatic metabolic stability and intestinal absorption. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Jing, X.; Wu, D.; Shi, Y. Methylation of genistein and kaempferol improves their affinities for proteins. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, I.L.; Chee, W.S.; Poulsen, L.; Offord-Cavin, E.; Rasmussen, S.E.; Frederiksen, H.; Enslen, M.; Barron, D.; Horcajada, M.N.; Williamson, G. Bioavailability is improved by enzymatic modification of the citrus flavonoid hesperidin in humans: A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 404–408. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3.0. 2011. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12354500/Data/Flav/Flav_R03.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2013).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for the Proanthocyanidin Content of Selected Foods. 2004. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12354500/Data/PA/PA.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2013).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for the Isoflavone Content of Selected Foods, Release 2.0. 2008. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12354500/Data/isoflav/Isoflav_R2.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2013).

- D’Archivio, M.; Filesi, C.; Di Benedetto, R.; Gargiulo, R.; Giovannini, C.; Masella, R. Polyphenols, dietary sources and bioavailability. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2007, 43, 348–361. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, J.; Liu, R.H. Apple phytochemicals and their health benefits. Nutr. J. 2004, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huber, G.M.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Phenolic profiles and antioxidant properties of apple skin extracts. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrhovsek, U.; Rigo, A.; Tonon, D.; Mattivi, F. Quantitation of polyphenols in different apple varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 6532–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasooriya, C.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Jamieson, A. Juice quality and polyphenol concentration of fresh fruits and pomace of selected Nov Scotia-grown grape cultivars. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2010, 90, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotito, S.; Frei, B. Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: Cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon? Free Radi. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 1727–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdylo, A.; Oszmianski, J.; Laskowski, P. Polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of new and old apple varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 6520–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, P.A.; Laranjinha, J.A.; de Freitas, V.A. Antioxidant protection of low density lipoprotein by proanthocyanidins: Structure/activity relationships. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 66, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimboor, R.; Arumughan, C. Effect of polymerization on antioxidant and xanthine oxidase inhibitory potential of sea buckthorn (H. rhamnoides) proanthocyanidins. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, C1036–C1041. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi-Kameyama, M.; Yanagida, A.; Kanda, T.; Nagata, T. Identification of catechin oligomers from apple (Malus pumila cv. Fuji) in matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and fast-atom bombardment mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 1997, 11, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Erkan, N.; Yasmin, A. Antioxidant protection of eicosapentaenoic acid and fish oil oxidation by polyphenolic-enriched apple skin extract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar]

- De Pascual-Teresa, S.; Moreno, D.A.; Garcia-Viguera, C. Flavanols and anthocyanins in cardiovascular health: A review of current evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1679–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srivastava, J.K.; Gupta, S. Extraction, characterization, stability and biological activity of flavonoids isolated from chamomile flowers. Mol. Cell. Pharmacol. 2009, 1, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Code of federal regulations, Title 21—Food and Drugs, Volume 5, Chapter 1—Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, Subchapter D—Drugs for Human Use, Part 320—Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Requirements. 2012. Available online: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=320.1&SearchTerm=bioavailability (accessed on 2 June 2013).

- Landete, J.M. Updated knowledge about polyphenols: Functions, bioavailability, metabolism, and health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Manach, C.; Remesy, C. Absorption and metabolism of polyphenols in the gut and impact on health. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002, 56, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Calani, L.; Scazzina, F.; Jechiu, L.; Cordero, C.; Brighenti, F. Bioavailability of catechins from ready-to-drink tea. Nutrition 2010, 26, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.P.; Schroeter, H.; Rechner, A.R.; Rice-Evans, C. Bioavailability of flavan-3-ols and procyanidins: Gastrointestinal tract influences and their relevance to bioactive forms in vivo. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2001, 3, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Thilakarathna, S.; Nair, S. Polyphenols of Apples and Their Potential Health Benefits. In Polyphenols: Chemistry, Dietary Sources and Health Benefits; Sun, J., Prasad, K.N., Ismail, A., Yang, B., You, X., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 333–368. [Google Scholar]

- Graefe, E.U.; Wittig, J.; Mueller, S.; Riethling, A.K.; Uehleke, B.; Drewelow, B.; Pforte, H.; Jacobasch, G.; Derendorf, H.; Veit, M. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of quercetin glycosides in humans. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 41, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mitchell, A.E. Pharmacokinetics of quercetin absorption from apples and onions in healthy humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3874–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, C.D.; Kroon, P.A.; Cassidy, A. The bioactivity of dietary anthocyanins is likely to be mediated by their degradation products. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, S92–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.; Nave, F.; Gonçalves, R.; de Freitas, V.; Mateus, N. On the bioavailability of flavanols and anthocyanins: Flavanol-anthocyanin dimers. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensma, A.; Faassen-Peters, M.A.; Noteborn, H.P.; Rietjens, I.M. Bioavailability of genistein and its glycoside genistin as measured in the portal vein of freely moving unanesthetized rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8006–8012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaze, F.I.; Bounartzi, M.I.; Georgarakis, M.; Niopas, I. Pharmacokinetics of the citrus flavanone aglycones hesperetin and naringenin after single oral administration in human subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 472–477. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, G.; Clifford, M.N. Colonic metabolites of berry polyphenols: The missing link to biological activity? Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, S48–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, T.; Masumoto, S.; Moriichi, N. Apple proanthocyanidin oligomers absorption in rats after oral administration: Analysis of proanthocyanidins in plasma using the porter method and high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollman, P.C.H.; van Trijp, J.M.P.; Buysman, M.N.C.P.; van der Gaag, M.S.; Mengelers, M.J.B.; de Vries, J.H.M.; Katan, M.B. Relative bioavailability of the antioxidant quercetin from various foods in man. FEBS Lett. 1997, 418, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollman, P.C.H.; Buijsman, M.N.C.P.; van Gameren, Y.; Cnossen, P.J.; de Vries, J.H.M.; Katan, M.B. The sugar moiety is a major determinant of the absorption of dietary flavonoid glycosides in man. Free Radic. Res. 1999, 31, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, T. Serial review: Flavonoids and isoflavones (phytoestrogens): Absorption, metabolism, and bioactivity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, T.; Mursu, J.; Heinonen, M.; Nurmi, A.; Hiltunen, R.; Voutilainen, S. Metabolism of berry anthocyanins to phenolic acids in humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2274–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.; Manach, C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. II. Review of 93 intervention studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 243S–255S. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa, K.; Yoshizumi, M.; Kawai, Y. Pharmacology in health food: Metabolism of quercetin in vivo and its protective effect against arteriosclerosis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 115, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moco, S.; Martin, F.P.; Rezzi, S. Metabolomics view on gut microbiome modulation by polyphenol-rich foods. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 4781–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, W.; Archeveque, M.A.; Edwards, C.A.; Matsumoto, H.; Crozier, A. Bioavailability and metabolism of orange juice flavanones in humans: Impact of a full-fat yogurt. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11157–11164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganath, I.B.; Mullen, W.; Edwards, C.A.; Crozier, A. The relative contribution of the small and large intestine to the absorption and metabolism of rutin in man. Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, I.; Faughnan, M.; Hoey, L.; Wahala, K.; Williamson, G.; Cassidy, A. Bioavailability of phyto-oestrogens. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 89, S45–S58. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, A. Dietary phyto-oestrogens: Molecular mechanisms, bioavailability and importance to menopausal health. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2005, 18, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, I.R.; Wiseman, H.; Sanders, T.A.; Adlercreutz, H.; Bowey, E.A. Interindividual variation in metabolism of soy isoflavones and lignans: Influence of habitual diet on equol production by the gut microflora. Nutr. Cancer 2000, 36, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafii, F.; Davis, C.; Park, M.; Heinze, T.M.; Beger, R.D. Variations in metabolism of the soy isoflavonoid daidzein by human intestinal microfloras from different individuals. Arch. Microbiol. 2003, 180, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setchell, K.D.; Brown, N.M.; Lydeking-Olsen, E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol-a clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 3577–3584. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides, P.P. Lipid microemulsions for improving drug dissolution and oral absorption: Physical and biopharmaceutical aspects. Pharm. Res. 1995, 12, 1561–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.L.; Li, H.W.; Zhou, M.Y.; Lu, W. Dispersion of daidzein with polyvinylpyrrolidone effects on dissolution rate and bioavailability. Zhong Yao Cai 2011, 34, 605–610. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Yu, H.J. Enhanced bioavailability of soy isoflavones by complexation with beta-cyclodextrin in rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 2927–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Walle, T. Methylation protects dietary flavonoids from rapid hepatic metabolism. Xenobiotica 2006, 36, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutto, L.; Marotta, E.; de Marchi, U.; Zoratti, M.; Paradisi, C. Ester-based precursors to increase the bioavailability of quercetin. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monobe, M.; Ema, K.; Tokuda, Y.; Maeda-Yamamoto, M. Increased plasma concentration of epigallocatechin in mice after orally administering a green tea (Camellia sinensis L.) extract supplemented by steamed rice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Kwik-Uribe, C.; Vidal, A.; Spencer, J.P. Influence of sugar type on the bioavailability of cocoa flavanols. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 2243–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egert, S.; Wolffram, S.; Schulze, B. Enriched cereal bars are more effective in increasing plasma quercetin compared with quercetin from powder-filled hard capsules. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Thilakarathna, S.H.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Flavonoid Bioavailability and Attempts for Bioavailability Enhancement. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3367-3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093367

Thilakarathna SH, Rupasinghe HPV. Flavonoid Bioavailability and Attempts for Bioavailability Enhancement. Nutrients. 2013; 5(9):3367-3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093367

Chicago/Turabian StyleThilakarathna, Surangi H., and H. P. Vasantha Rupasinghe. 2013. "Flavonoid Bioavailability and Attempts for Bioavailability Enhancement" Nutrients 5, no. 9: 3367-3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093367

APA StyleThilakarathna, S. H., & Rupasinghe, H. P. V. (2013). Flavonoid Bioavailability and Attempts for Bioavailability Enhancement. Nutrients, 5(9), 3367-3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093367