Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Assessment in 3D Cellular Models

Abstract

:1. Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity

2. Treatment of Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity

3. Existing In Vitro Models for Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Testing

3.1. Two-Dimensional Culture

3.2. Rodent Experiments

4. Three-Dimensional Renal Culture Models for Predicting Nephrotoxicity

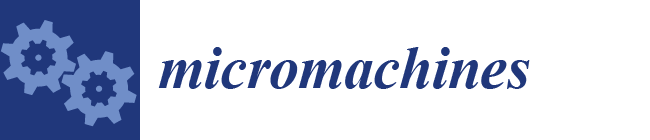

5. In Vitro 3D Kidney Models

5.1. Spheroids

5.2. Organoids

5.3. Three-Dimensional (3D) Tissue-Engineered Kidney Model

5.4. Kidney-on-Chips

6. Cell Types for 3D Culture Models

6.1. Animal Primary Renal Cells

6.2. Human-Derived Immortalized Cells Lines

6.3. Animal Immortalized Cells Lines

6.4. Human ESC/Human iPSC

6.5. Human Urine-Derived Stem Cells

7. Methods to Induce Stem Cells to Give Rise to Renal Cells

8. Procedures to Set Up 3D Models for Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Testing

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jha, V.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Iseki, K.; Li, Z.; Naicker, S.; Plattner, B.; Saran, R.; Wang, A.Y.; Yang, C.W. Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013, 382, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.J.; Foley, R.N.; Chavers, B.; Gilbertson, D.; Herzog, C.; Johansen, K.; Kasiske, B.; Kutner, N.; Liu, J.; St Peter, W.; et al. United States Renal Data System 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease & end-stage renal disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012, 59, A1–A7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Chen, X.; Ding, X.; Teng, J. Analysis of the high incidence of acute kidney injury associated with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatol. Int. 2018, 12, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singbartl, K.; Kellum, J.A. AKI in the ICU: Definition, epidemiology, risk stratification, and outcomes. Kidney Int. 2012, 81, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perazella, M.A. Drug use and nephrotoxicity in the intensive care unit. Kidney Int. 2012, 81, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mukherjee, K.; Chio, T.I.; Gu, H.; Sackett, D.L.; Bane, S.L.; Sever, S. A Novel Fluorogenic Assay for the Detection of Nephrotoxin-Induced Oxidative Stress in Live Cells and Renal Tissue. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2523–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajavi Rad, A.; Mohebbati, R.; Hosseinian, S. Drug-induced Nephrotoxicity and Medicinal Plants. Iran J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 11, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis-Ajami, M.L.; Fink, J.C.; Wu, J. Nephrotoxic Medication Exposure in U.S. Adults with Predialysis Chronic Kidney Disease: Health Services Utilization and Cost Outcomes. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2016, 22, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.; Ahmed, S.; Gerritsen, K.G.F.; Mihaila, S.M.; Masereeuw, R. Kidney-based in vitro models for drug-induced toxicity testing. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 3397–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schetz, M.; Dasta, J.; Goldstein, S.; Golper, T. Drug-induced acute kidney injury. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2005, 11, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisoni, R.; Ruggenenti, P.; Remuzzi, G. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: Incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2001, 24, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, P.J.; Sipols, J.M.; George, J.N. Drug-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2001, 8, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momper, J.D.; Nigam, S.K. Developmental regulation of kidney and liver solute carrier and ATP-binding cassette drug transporters and drug metabolizing enzymes: The role of remote organ communication. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Bai, Y.; Jayne, L.A.; Hector, R.D.; Persaud, A.K.; Ong, S.S.; Rojesh, S.; Raj, R.; Feng, M.; Chung, S.; et al. A kinome-wide screen identifies a CDKL5-SOX9 regulatory axis in epithelial cell death and kidney injury. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sancho-Martinez, S.M.; Lopez-Novoa, J.M.; Lopez-Hernandez, F.J. Pathophysiological role of different tubular epithelial cell death modes in acute kidney injury. Clin. Kidney J. 2015, 8, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamoulakis, C.; Tsarouhas, K.; Fragkiadoulaki, I.; Heretis, I.; Wilks, M.F.; Spandidos, D.A.; Tsitsimpikou, C.; Tsatsakis, A. Contrast-induced nephropathy: Basic concepts, pathophysiological implications and prevention strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 180, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, P.; Rodrigues, A.D.; Steppan, C.M.; Engle, S.J.; Mathialagan, S.; Schroeter, T. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Kidney Model for Nephrotoxicity Studies. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morizane, R.; Lam, A.Q.; Freedman, B.S.; Kishi, S.; Valerius, M.T.; Bonventre, J.V. Nephron organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells model kidney development and injury. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- DesRochers, T.M.; Suter, L.; Roth, A.; Kaplan, D.L. Bioengineered 3D human kidney tissue, a platform for the determination of nephrotoxicity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumar, P.; Rohilla, A.; Thangathirupathi, A. Gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity: Do we have a promising therapeutic approach to blunt it? Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 62, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdale, P.R.; Dev, I.; Ayanur, A.; Singh, D.; Arshad, M.; Ansari, K.M. Safety evaluation of Ochratoxin A and Citrinin after 28 days repeated dose oral exposure to Wistar rats. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 115, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takasato, M.; Er, P.X.; Chiu, H.S.; Maier, B.; Baillie, G.J.; Ferguson, C.; Parton, R.G.; Wolvetang, E.J.; Roost, M.S.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; et al. Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis. Nature 2015, 526, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerniecki, S.M.; Cruz, N.M.; Harder, J.L.; Menon, R.; Annis, J.; Otto, E.A.; Gulieva, R.E.; Islas, L.V.; Kim, Y.K.; Tran, L.M.; et al. High-Throughput Screening Enhances Kidney Organoid Differentiation from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells and Enables Automated Multidimensional Phenotyping. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 929–940.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

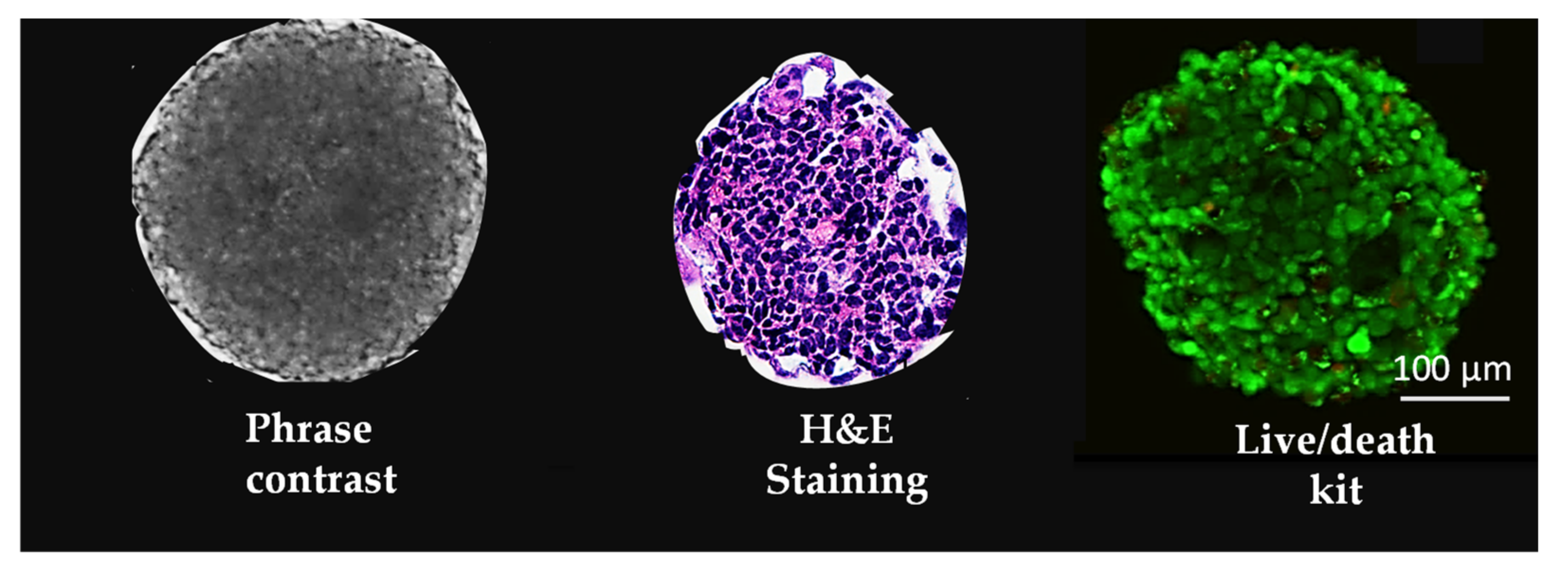

- Ding, B.; Sun, G.; Liu, S.; Peng, E.; Wan, M.; Chen, L.; Jackson, J.; Atala, A. Three-Dimensional Renal Organoids from Whole Kidney Cells: Generation, Optimization, and Potential Application in Nephrotoxicology In Vitro. Cell Transplant. 2020, 29, 963689719897066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Astashkina, A.I.; Mann, B.K.; Prestwich, G.D.; Grainger, D.W. A 3-D organoid kidney culture model engineered for high-throughput nephrotoxicity assays. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 4700–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedecostante, M.; Westphal, K.G.C.; Buono, M.F.; Sanchez Romero, N.; Wilmer, M.J.; Kerkering, J.; Baptista, P.M.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Masereeuw, R. Recellularized Native Kidney Scaffolds as a Novel Tool in Nephrotoxicity Screening. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Ding, B.; Wan, M.; Chen, L.; Jackson, J.; Atala, A. Formation and optimization of three-dimensional organoids generated from urine-derived stem cells for renal function in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Deng, N.; Dou, L.; Ding, H.; Criswell, T.; Atala, A.; Furdui, C.M.; Zhang, Y. 3-D Human Renal Tubular Organoids Generated from Urine-Derived Stem Cells for Nephrotoxicity Screening. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 6701–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabla, N.; Dong, Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: Mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elmeliegy, M.; Vourvahis, M.; Guo, C.; Wang, D.D. Effect of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) Inducers on Exposure of P-gp Substrates: Review of Clinical Drug-Drug Interaction Studies. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2020, 59, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, E.M.; Hewitt, W.R. Dose-response relationships in ketone-induced potentiation of chloroform hepato- and nephrotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1984, 76, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, S.; Mudassir, S.; Toor, R.S. Histological Effects of Nigella Sativa on Aspirin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Albino Rats. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2018, 28, 735–738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Imaoka, T.; Kusuhara, H.; Adachi-Akahane, S.; Hasegawa, M.; Morita, N.; Endou, H.; Sugiyama, Y. The renal-specific transporter mediates facilitative transport of organic anions at the brush border membrane of mouse renal tubules. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perazella, M.A. Drug-induced acute kidney injury: Diverse mechanisms of tubular injury. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2019, 25, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, R.C.; van Kooten, C.; van de Lagemaat-Paape, M.E.; Daha, M.R.; Paul, L.C. Renal tubular epithelial cell death and cyclosporin A. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002, 17, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Betton, G.R.; Kenne, K.; Somers, R.; Marr, A. Protein biomarkers of nephrotoxicity: A review and findings with cyclosporin A, a signal transduction kinase inhibitor and N-phenylanthranilic acid. Cancer Biomark. 2005, 1, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; He, W.; Xia, P.; Sun, W.; Shi, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, B.; Zhu, J.; et al. Total Extracts of Abelmoschus manihot L. Attenuates Adriamycin-Induced Renal Tubule Injury via Suppression of ROS-ERK1/2-Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klos, C.; Koob, M.; Kramer, C.; Dekant, W. p-aminophenol nephrotoxicity: Biosynthesis of toxic glutathione conjugates. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1992, 115, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, G.; Favret, G.; Catone, B.; Bartoli, E. The effect of colchicine on proximal tubular reabsorption. Pharmacol. Res. 2000, 41, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, M.; Ramm, S.; Hafner, M.; Muhlich, J.L.; Gottwald, E.M.; Weber, E.; Jaklic, A.; Ajay, A.K.; Svoboda, D.; Auerbach, S.; et al. A Quantitative Approach to Screen for Nephrotoxic Compounds In Vitro. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faiz, H.; Boghossian, M.; Martin, G.; Baverel, G.; Ferrier, B.; Conjard-Duplany, A. Cadmium chloride inhibits lactate gluconeogenesis in mouse renal proximal tubules: An in vitro metabolomic approach with 13C NMR. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 238, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.V.; Er, P.X.; Lawlor, K.T.; Motazedian, A.; Scurr, M.; Ghobrial, I.; Combes, A.N.; Zappia, L.; Oshlack, A.; Stanley, E.G.; et al. Kidney micro-organoids in suspension culture as a scalable source of human pluripotent stem cell-derived kidney cells. Development 2019, 146, dev172361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Musah, S.; Mammoto, A.; Ferrante, T.C.; Jeanty, S.S.F.; Hirano-Kobayashi, M.; Mammoto, T.; Roberts, K.; Chung, S.; Novak, R.; Ingram, M.; et al. Mature induced-pluripotent-stem-cell-derived human podocytes reconstitute kidney glomerular-capillary-wall function on a chip. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrosyan, A.; Cravedi, P.; Villani, V.; Angeletti, A.; Manrique, J.; Renieri, A.; De Filippo, R.E.; Perin, L.; Da Sacco, S. A glomerulus-on-a-chip to recapitulate the human glomerular filtration barrier. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paueksakon, P.; Fogo, A.B. Drug-induced nephropathies. Histopathology 2017, 70, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perazella, M.A.; Markowitz, G.S. Bisphosphonate nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Srivastava, T.; Heruth, D.P.; Duncan, R.S.; Rezaiekhaligh, M.H.; Garola, R.E.; Priya, L.; Zhou, J.; Boinpelly, V.C.; Novak, J.; Ali, M.F.; et al. Transcription Factor beta-Catenin Plays a Key Role in Fluid Flow Shear Stress-Mediated Glomerular Injury in Solitary Kidney. Cells 2021, 10, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, C.A. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am. Fam. Physician 2008, 78, 743–750. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, K.S.; Obert, L.A. Drug-induced Glomerulonephritis: The Spectre of Biotherapeutic and Antisense Oligonucleotide Immune Activation in the Kidney. Toxicol. Pathol. 2018, 46, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moledina, D.G.; Perazella, M.A. Drug-Induced Acute Interstitial Nephritis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 2046–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, G.S.; Perazella, M.A. Drug-induced renal failure: A focus on tubulointerstitial disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2005, 351, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Li, L.X.; Harris, P.C.; Yang, J.; Li, X. Extracellular vesicles and exosomes generated from cystic renal epithelial cells promote cyst growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramann, R.; Tanaka, M.; Humphreys, B.D. Fluorescence microangiography for quantitative assessment of peritubular capillary changes after AKI in mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 1924–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunn, K.W.; Sutton, T.A.; Sandoval, R.M. Live-Animal Imaging of Renal Function by Multiphoton Microscopy. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2018, 41, 12.9.1–12.9.18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verma, S.K.; Molitoris, B.A. Renal endothelial injury and microvascular dysfunction in acute kidney injury. Semin. Nephrol. 2015, 35, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dimke, H.; Sparks, M.A.; Thomson, B.R.; Frische, S.; Coffman, T.M.; Quaggin, S.E. Tubulovascular cross-talk by vascular endothelial growth factor a maintains peritubular microvasculature in kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lameire, N. Nephrotoxicity of recent anti-cancer agents. Clin. Kidney J. 2014, 7, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Nouri, Z.L.; Reese, J.A.; Terrell, D.R.; Vesely, S.K.; George, J.N. Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: A systematic review of published reports. Blood 2015, 125, 616–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Sun, Y.; Shi, X.; Shen, H.; Ning, H.; Liu, H. 3D printing of tissue engineering scaffolds: A focus on vascular regeneration. Biodes Manuf. 2021, 4, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Shad, F.; Smith, M.C. Acute kidney injury: A guide to diagnosis and management. Am. Fam. Physician 2012, 86, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kellum, J.A.; Lameire, N.; Group, K.A.G.W. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: A KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit. Care 2013, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Port, F.K.; Eknoyan, G. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) and the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI): A cooperative initiative to improve outcomes for hemodialysis patients worldwide. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2004, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, R.; Kellum, J.A. Acute kidney injury: What’s the prognosis? Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2011, 7, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bajaj, P.; Chowdhury, S.K.; Yucha, R.; Kelly, E.J.; Xiao, G. Emerging Kidney Models to Investigate Metabolism, Transport, and Toxicity of Drugs and Xenobiotics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, C.D.; Sayer, R.; Windass, A.S.; Haslam, I.S.; De Broe, M.E.; D’Haese, P.C.; Verhulst, A. Characterisation of human tubular cell monolayers as a model of proximal tubular xenobiotic handling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008, 233, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasnim, F.; Zink, D. Cross talk between primary human renal tubular cells and endothelial cells in cocultures. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2012, 302, F1055–F1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astashkina, A.I.; Mann, B.K.; Prestwich, G.D.; Grainger, D.W. Comparing predictive drug nephrotoxicity biomarkers in kidney 3-D primary organoid culture and immortalized cell lines. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 4712–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barre-Sinoussi, F.; Montagutelli, X. Animal models are essential to biological research: Issues and perspectives. Future Sci. OA 2015, 1, FSO63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neves, F.; Abrantes, J.; Almeida, T.; de Matos, A.L.; Costa, P.P.; Esteves, P.J. Genetic characterization of interleukins (IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-4, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12A, IL-12B, IL-15 and IL-18) with relevant biological roles in lagomorphs. Innate Immun. 2015, 21, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Soo, J.Y.; Jansen, J.; Masereeuw, R.; Little, M.H. Advances in predictive in vitro models of drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, B.A.; Badr, N.A.; Felder, R.A. 3D cell culture opens new dimensions in cell-based assays. Drug Discov. Today 2009, 14, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhans, S.A. Three-Dimensional in Vitro Cell Culture Models in Drug Discovery and Drug Repositioning. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riss, T.; Trask, O.J., Jr. Factors to consider when interrogating 3D culture models with plate readers or automated microscopes. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2021, 57, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelants, C.; Pillet, C.; Franquet, Q.; Sarrazin, C.; Peilleron, N.; Giacosa, S.; Guyon, L.; Fontanell, A.; Fiard, G.; Long, J.A.; et al. Ex-Vivo Treatment of Tumor Tissue Slices as a Predictive Preclinical Method to Evaluate Targeted Therapies for Patients with Renal Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kashaninejad, N.; Chan, W.K.; Nguyen, N.T. Eccentricity effect of micropatterned surface on contact angle. Langmuir 2012, 28, 4793–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kashaninejad, N.; Nikmaneshi, M.R.; Moghadas, H.; Kiyoumarsi Oskouei, A.; Rismanian, M.; Barisam, M.; Saidi, M.S.; Firoozabadi, B. Organ-Tumor-on-a-Chip for Chemosensitivity Assay: A Critical Review. Micromachines 2016, 7, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esch, E.W.; Bahinski, A.; Huh, D. Organs-on-chips at the frontiers of drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhise, N.S.; Ribas, J.; Manoharan, V.; Zhang, Y.S.; Polini, A.; Massa, S.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Khademhosseini, A. Organ-on-a-chip platforms for studying drug delivery systems. J. Control Release 2014, 190, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Polini, A.; Prodanov, L.; Bhise, N.S.; Manoharan, V.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Khademhosseini, A. Organs-on-a-chip: A new tool for drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2014, 9, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, K.J.; Suh, K.Y. A multi-layer microfluidic device for efficient culture and analysis of renal tubular cells. Lab Chip. 2010, 10, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, K.J.; Mehr, A.P.; Hamilton, G.A.; McPartlin, L.A.; Chung, S.; Suh, K.Y.; Ingber, D.E. Human kidney proximal tubule-on-a-chip for drug transport and nephrotoxicity assessment. Integr. Biol. 2013, 5, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, T.H.; Fornoni, A. Nonimmunologic targets of immunosuppressive agents in podocytes. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 34, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Friedrich, C.; Endlich, N.; Kriz, W.; Endlich, K. Podocytes are sensitive to fluid shear stress in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2006, 291, F856–F865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mashanov, G.I.; Nenasheva, T.A.; Mashanova, T.; Maclachlan, C.; Birdsall, N.J.M.; Molloy, J.E. A method for imaging single molecules at the plasma membrane of live cells within tissue slices. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021, 153, e202012657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschnick, N.; Drees, D.; Redder, E.; Erapaneedi, R.; Pereira da Graca, A.; Schafers, M.; Jiang, X.; Kiefer, F. Rapid methods for the evaluation of fluorescent reporters in tissue clearing and the segmentation of large vascular structures. iScience 2021, 24, 102650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, B.S.; Brooks, C.R.; Lam, A.Q.; Fu, H.; Morizane, R.; Agrawal, V.; Saad, A.F.; Li, M.K.; Hughes, M.R.; Werff, R.V.; et al. Modelling kidney disease with CRISPR-mutant kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent epiblast spheroids. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilmer, M.J.; Ng, C.P.; Lanz, H.L.; Vulto, P.; Suter-Dick, L.; Masereeuw, R. Kidney-on-a-Chip Technology for Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Screening. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, A.; Kaku, Y.; Ohmori, T.; Sharmin, S.; Ogawa, M.; Sasaki, H.; Nishinakamura, R. Redefining the in vivo origin of metanephric nephron progenitors enables generation of complex kidney structures from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schutgens, F.; Rookmaaker, M.B.; Margaritis, T.; Rios, A.; Ammerlaan, C.; Jansen, J.; Gijzen, L.; Vormann, M.; Vonk, A.; Viveen, M.; et al. Tubuloids derived from human adult kidney and urine for personalized disease modeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Taguchi, A.; Tanigawa, S.; Yatsuda, J.; Kamba, T.; Takahashi, S.; Kurihara, H.; Mukoyama, M.; Nishinakamura, R. Manipulation of Nephron-Patterning Signals Enables Selective Induction of Podocytes from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiderhoff, T.; Himmerkus, N.; Stuiver, M.; Mutig, K.; Will, C.; Meij, I.C.; Bachmann, S.; Bleich, M.; Willnow, T.E.; Muller, D. Deletion of claudin-10 (Cldn10) in the thick ascending limb impairs paracellular sodium permeability and leads to hypermagnesemia and nephrocalcinosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14241–14246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dimke, H.; Desai, P.; Borovac, J.; Lau, A.; Pan, W.; Alexander, R.T. Activation of the Ca2+-sensing receptor increases renal claudin-14 expression and urinary Ca2+ excretion. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2013, 304, F761–F769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olofsson, B.; Korpelainen, E.; Pepper, M.S.; Mandriota, S.J.; Aase, K.; Kumar, V.; Gunji, Y.; Jeltsch, M.M.; Shibuya, M.; Alitalo, K.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGF-B) binds to VEGF receptor-1 and regulates plasminogen activator activity in endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 11709–11714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Low, J.H.; Li, P.; Chew, E.G.Y.; Zhou, B.; Suzuki, K.; Zhang, T.; Lian, M.M.; Liu, M.; Aizawa, E.; Rodriguez Esteban, C.; et al. Generation of Human PSC-Derived Kidney Organoids with Patterned Nephron Segments and a De Novo Vascular Network. Cell Stem Cell. 2019, 25, 373–387.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, L.J.; Howden, S.E.; Phipson, B.; Lonsdale, A.; Er, P.X.; Ghobrial, I.; Hosawi, S.; Wilson, S.; Lawlor, K.T.; Khan, S.; et al. 3D organoid-derived human glomeruli for personalised podocyte disease modelling and drug screening. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bulow, R.D.; Boor, P. Extracellular Matrix in Kidney Fibrosis: More Than Just a Scaffold. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2019, 67, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Finesilver, G.; Bailly, J.; Kahana, M.; Mitrani, E. Kidney derived micro-scaffolds enable HK-2 cells to develop more in-vivo like properties. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 322, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonandrini, B.; Figliuzzi, M.; Papadimou, E.; Morigi, M.; Perico, N.; Casiraghi, F.; Dipl, C.; Sangalli, F.; Conti, S.; Benigni, A.; et al. Recellularization of well-preserved acellular kidney scaffold using embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng. Part A 2014, 20, 1486–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Batchelder, C.A.; Martinez, M.L.; Tarantal, A.F. Natural Scaffolds for Renal Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells for Kidney Tissue Engineering. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uzarski, J.S.; Su, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Z.J.; Ward, H.H.; Wandinger-Ness, A.; Miller, W.M.; Wertheim, J.A. Epithelial Cell Repopulation and Preparation of Rodent Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds for Renal Tissue Development. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 102, e53271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kharkar, P.M.; Kiick, K.L.; Kloxin, A.M. Designing degradable hydrogels for orthogonal control of cell microenvironments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7335–7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Vlierberghe, S.; Dubruel, P.; Schacht, E. Biopolymer-based hydrogels as scaffolds for tissue engineering applications: A review. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1387–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Silva, E.A.; Mooney, D.J. Growth factor delivery-based tissue engineering: General approaches and a review of recent developments. J. R. Soc. Interface 2011, 8, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nichol, J.W.; Koshy, S.T.; Bae, H.; Hwang, C.M.; Yamanlar, S.; Khademhosseini, A. Cell-laden microengineered gelatin methacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5536–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jansen, K.; Schuurmans, C.C.L.; Jansen, J.; Masereeuw, R.; Vermonden, T. Hydrogel-Based Cell Therapies for Kidney Regeneration: Current Trends in Biofabrication and In Vivo Repair. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 3845–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Costa, K.; Kosic, M.; Lam, A.; Moradipour, A.; Zhao, Y.; Radisic, M. Biomaterials and Culture Systems for Development of Organoid and Organ-on-a-Chip Models. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 2002–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Xin, J.; Pollock, D.M.; Pollock, J.S. Shear stress-mediated NO production in inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2000, 279, F270–F274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, V.; Weisz, O.A. Discerning the role of mechanosensors in regulating proximal tubule function. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2016, 310, F1–F5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ong, L.J.Y.; Zhu, L.; Tan, G.J.S.; Toh, Y.C. Quantitative Image-Based Cell Viability (QuantICV) Assay for Microfluidic 3D Tissue Culture Applications. Micromachines 2020, 11, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vriend, J.; Nieskens, T.T.G.; Vormann, M.K.; van den Berge, B.T.; van den Heuvel, A.; Russel, F.G.M.; Suter-Dick, L.; Lanz, H.L.; Vulto, P.; Masereeuw, R.; et al. Screening of Drug-Transporter Interactions in a 3D Microfluidic Renal Proximal Tubule on a Chip. AAPS J. 2018, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theobald, J.; Ghanem, A.; Wallisch, P.; Banaeiyan, A.A.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Taskova, K.; Haltmeier, M.; Kurtz, A.; Becker, H.; Reuter, S.; et al. Liver-Kidney-on-Chip To Study Toxicity of Drug Metabolites. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duzagac, F.; Saorin, G.; Memeo, L.; Canzonieri, V.; Rizzolio, F. Microfluidic Organoids-on-a-Chip: Quantum Leap in Cancer Research. Cancers 2021, 13, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.J.; Johnson, G.; Kirk, J.; Fuerstenberg, S.M.; Zager, R.A.; Torok-Storb, B. HK-2: An immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal adult human kidney. Kidney Int. 1994, 45, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prozialeck, W.C.; Edwards, J.R.; Lamar, P.C.; Smith, C.S. Epithelial barrier characteristics and expression of cell adhesion molecules in proximal tubule-derived cell lines commonly used for in vitro toxicity studies. Toxicol. In Vitro 2006, 20, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.K.; Nam, S.A.; Yang, C.W. Applications of kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prozialeck, W.C.; Edwards, J.R. Cell adhesion molecules in chemically-induced renal injury. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 114, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nieskens, T.T.; Peters, J.G.; Schreurs, M.J.; Smits, N.; Woestenenk, R.; Jansen, K.; van der Made, T.K.; Roring, M.; Hilgendorf, C.; Wilmer, M.J.; et al. A Human Renal Proximal Tubule Cell Line with Stable Organic Anion Transporter 1 and 3 Expression Predictive for Antiviral-Induced Toxicity. AAPS J. 2016, 18, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stray, K.M.; Bam, R.A.; Birkus, G.; Hao, J.; Lepist, E.I.; Yant, S.R.; Ray, A.S.; Cihlar, T. Evaluation of the effect of cobicistat on the in vitro renal transport and cytotoxicity potential of tenofovir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4982–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uetake, R.; Sakurai, T.; Kamiyoshi, A.; Ichikawa-Shindo, Y.; Kawate, H.; Iesato, Y.; Yoshizawa, T.; Koyama, T.; Yang, L.; Toriyama, Y.; et al. Adrenomedullin-RAMP2 system suppresses ER stress-induced tubule cell death and is involved in kidney protection. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasato, M.; Er, P.X.; Becroft, M.; Vanslambrouck, J.M.; Stanley, E.G.; Elefanty, A.G.; Little, M.H. Directing human embryonic stem cell differentiation towards a renal lineage generates a self-organizing kidney. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, A.Q.; Freedman, B.S.; Morizane, R.; Lerou, P.H.; Valerius, M.T.; Bonventre, J.V. Rapid and efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intermediate mesoderm that forms tubules expressing kidney proximal tubular markers. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, G.; Wu, R.; Yang, B.; Deng, C.; Lu, X.; Walker, S.J.; Ma, P.X.; Mou, S.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Human Urine-Derived Stem Cell Differentiation to Endothelial Cells with Barrier Function and Nitric Oxide Production. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; McNeill, E.; Tian, H.; Soker, S.; Andersson, K.E.; Yoo, J.J.; Atala, A. Urine derived cells are a potential source for urological tissue reconstruction. J. Urol. 2008, 180, 2226–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Liu, G.; Shi, Y.; Wu, R.; Yang, B.; He, T.; Fan, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; et al. Multipotential differentiation of human urine-derived stem cells: Potential for therapeutic applications in urology. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1840–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.J.; Sigurdson, W.J.; Nickerson, P.A.; Taub, M. Both mitogen activated protein kinase and the mammalian target of rapamycin modulate the development of functional renal proximal tubules in matrigel. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arakawa, H.; Washio, I.; Matsuoka, N.; Kubo, H.; Staub, A.Y.; Nakamichi, N.; Ishiguro, N.; Kato, Y.; Nakanishi, T.; Tamai, I. Usefulness of kidney slices for functional analysis of apical reabsorptive transporters. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McNeil, E.; Capaldo, C.T.; Macara, I.G. Zonula occludens-1 function in the assembly of tight junctions in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 1922–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gunness, P.; Aleksa, K.; Kosuge, K.; Ito, S.; Koren, G. Comparison of the novel HK-2 human renal proximal tubular cell line with the standard LLC-PK1 cell line in studying drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 88, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClane, B.A.; Chakrabarti, G. New insights into the cytotoxic mechanisms of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. Anaerobe 2004, 10, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iuchi, K.; Oya, K.; Hosoya, K.; Sasaki, K.; Sakurada, Y.; Nakano, T.; Hisatomi, H. Different morphologies of human embryonic kidney 293T cells in various types of culture dishes. Cytotechnology 2020, 72, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prange, J.A.; Bieri, M.; Segerer, S.; Burger, C.; Kaech, A.; Moritz, W.; Devuyst, O. Human proximal tubule cells form functional microtissues. Pflug. Arch. 2016, 468, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.; Fan, P.; Liu, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; Bai, H. Migration of Human Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells in Response to Physiological Electric Signals. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 724012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secker, P.F.; Luks, L.; Schlichenmaier, N.; Dietrich, D.R. RPTEC/TERT1 cells form highly differentiated tubules when cultured in a 3D matrix. ALTEX 2018, 35, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, J.; Fedecostante, M.; Wilmer, M.J.; Peters, J.G.; Kreuser, U.M.; van den Broek, P.H.; Mensink, R.A.; Boltje, T.J.; Stamatialis, D.; Wetzels, J.F.; et al. Bioengineered kidney tubules efficiently excrete uremic toxins. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedecostante, M.; Onciu, O.G.; Westphal, K.G.C.; Masereeuw, R. Towards a bioengineered kidney: Recellularization strategies for decellularized native kidney scaffolds. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2017, 40, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, L.E.; Zegers, M.M.; Mostov, K.E. Opinion: Building epithelial architecture: Insights from three-dimensional culture models. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, M.; Furusawa, K.; Mizutani, T.; Kawabata, K.; Haga, H. Three-dimensional morphogenesis of MDCK cells induced by cellular contractile forces on a viscous substrate. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Su, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, J.; Han, J.; Chen, L.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, B.; Dai, J. The effect of forced growth of cells into 3D spheres using low attachment surfaces on the acquisition of stemness properties. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3215–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hueso, M.; Navarro, E.; Sandoval, D.; Cruzado, J.M. Progress in the Development and Challenges for the Use of Artificial Kidneys and Wearable Dialysis Devices. Kidney Dis. 2019, 5, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terashima, M.; Fujita, Y.; Sugano, K.; Asano, M.; Kagiwada, N.; Sheng, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Hasegawa, A.; Kakuta, T.; Saito, A. Evaluation of water and electrolyte transport of tubular epithelial cells under osmotic and hydraulic pressure for development of bioartificial tubules. Artif. Organs 2001, 25, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, H.; Watanabe, J.; Konno, T.; Takai, M.; Saito, A.; Ishihara, K. Asymmetrically functional surface properties on biocompatible phospholipid polymer membrane for bioartificial kidney. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 77, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.L.; Mesch, L.; Schulz, I.; Becker, H.; Raible, J.; Kiessling, H.; Werner, S.; Rothbauer, U.; Schmees, C.; Busche, M.; et al. Parallelizable Microfluidic Platform to Model and Assess In Vitro Cellular Barriers: Technology and Application to Study the Interaction of 3D Tumor Spheroids with Cellular Barriers. Biosensors 2021, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M. Accelerating maturation of kidney organoids. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Q.; Xiong, G.; Liu, G.; Shupe, T.D.; Wei, G.; Zhang, D.; Liang, D.; Lu, X.; Atala, A.; Zhang, Y. Urothelium with barrier function differentiated from human urine-derived stem cells for potential use in urinary tract reconstruction. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, L.L.; Combes, A.N.; Short, K.M.; Lindstrom, N.O.; Whitney, P.H.; Cullen-McEwen, L.A.; Ju, A.; Abdelhalim, A.; Michos, O.; Bertram, J.F.; et al. Wnt11 directs nephron progenitor polarity and motile behavior ultimately determining nephron endowment. Elife 2018, 7, e40392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morizane, R.; Bonventre, J.V. Kidney Organoids: A Translational Journey. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taguchi, A.; Nishinakamura, R. Higher-Order Kidney Organogenesis from Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 730–746.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ryan, A.R.; England, A.R.; Chaney, C.P.; Cowdin, M.A.; Hiltabidle, M.; Daniel, E.; Gupta, A.K.; Oxburgh, L.; Carroll, T.J.; Cleaver, O. Vascular deficiencies in renal organoids and ex vivo kidney organogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2021, 477, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariharan, K.; Reinke, P.; Kurtz, A. Generating Multiple Kidney Progenitors and Cell Types from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1926, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magella, B.; Adam, M.; Potter, A.S.; Venkatasubramanian, M.; Chetal, K.; Hay, S.B.; Salomonis, N.; Potter, S.S. Cross-platform single cell analysis of kidney development shows stromal cells express Gdnf. Dev. Biol. 2018, 434, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherie-Lachidan, M.; Reginensi, A.; Pan, Q.; Zaveri, H.P.; Scott, D.A.; Blencowe, B.J.; Helmbacher, F.; McNeill, H. Stromal Fat4 acts non-autonomously with Dchs1/2 to restrict the nephron progenitor pool. Development 2015, 142, 2564–2573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mao, Y.; Francis-West, P.; Irvine, K.D. Fat4/Dchs1 signaling between stromal and cap mesenchyme cells influences nephrogenesis and ureteric bud branching. Development 2015, 142, 2574–2585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Humphreys, B.D.; Lin, S.L.; Kobayashi, A.; Hudson, T.E.; Nowlin, B.T.; Bonventre, J.V.; Valerius, M.T.; McMahon, A.P.; Duffield, J.S. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kobayashi, A.; Mugford, J.W.; Krautzberger, A.M.; Naiman, N.; Liao, J.; McMahon, A.P. Identification of a multipotent self-renewing stromal progenitor population during mammalian kidney organogenesis. Stem Cell Rep. 2014, 3, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lemos, D.R.; McMurdo, M.; Karaca, G.; Wilflingseder, J.; Leaf, I.A.; Gupta, N.; Miyoshi, T.; Susa, K.; Johnson, B.G.; Soliman, K.; et al. Interleukin-1beta Activates a MYC-Dependent Metabolic Switch in Kidney Stromal Cells Necessary for Progressive Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 1690–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Methods | Renal Tubule Epithelia Cells | Podocytes Stromal Cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | Targeted Cells | Drugs | Drugs | |

| Drugs, chemicals, or toxic agents with different doses | Gentamicin [17,18,19,20] Citrinin [17,21] Cisplatin [17,18,19,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] Rifampicin [17,30] Acetone [25,28,31] Aspirin [24,27,32] Penicillin G [24,27,33] Tenofovir [26,34] Cyclosporin A [26,35,36] Adriamycin [19,25,37] 4-aminophenol (PAP) [25,38] Colchicine [25,39] Cadmium chloride [40,41] | Brush border membrane of the proximal tubules S2 proximal tubular segment Basolateral membrane of proximal tubules Apical membrane of renal proximal tubules S1 and S2 proximal tubular segment Loop of Henle Brush border membrane of the proximal tubules Basolateral mem-brane of proximal tubules Brush border membrane of the proximal tubules/Thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle Brush border membrane of the proximal tubules Loop of Henle S3 proximal tubular segment S1 proximal tubular segment | Doxorubicin [17,42,43] Aspirin [27] Penicillin G [27] Puromycin-aminonucleoside [17,44] Adriamycin [42,43] | Doxorubicin [17,43] Puromycin-aminonucleoside [17] |

| Time-frames | 24 h [17,18,22,26] 48 h [18,24,27,40] 72 h [19,25,28] 2 wks [19] | 60 min [44] 24 h [17,22,42] 48 h [27] 5 days [43] | 24 h [17] 5 days [43] | |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| Gene markers | Kim-1 [17,18,23,24] HO-1 [17] | NPHS1 [17,42] WT1 [17] SYNPO [42] | ||

| Protein markers | Kim-1 [18,19,25,28,40] CYP2E1 [25,28] HO-1 [40] NGAL [19] AQP1 IL-6 [25] TNF [25] MCP-1 [25] IL-1b [25] MIP-1a [25] Rantes [25] Cleaved-caspase 3 [22] | |||

| Models | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| 2D culture | -Robust model -Easy to assess, manipulate -Cost- and time-efficient -Large scale -Retention of key metabolic | -Static model -Dedifferentiation -Lack of in vivo-like morphologic and phenotypic characteristics -Low complexity -Little predictive -Poor physiological or clinical relevance |

| 3D culture | -In vivo-like cell shape -More physiologic characteristics -Response to toxic insults with biomarkers found in vivo -3D paracrine and autocrine signaling; -Potential penetration gradients toward center -Cells of different stages (proliferating, hypoxic, quiescent, and necrotic) possible -More similar to in vivo expression profiles -Better predictive values to in vivo compound responses | -Cost-intensive -Simplified architecture -Can be variable -Less amenable to HTS/HCS -Hard to reach in vivo maturity -Complication in assay -Lack vasculature -May lack key cell types |

| Animal models | -Physiological resemblance -Well established -Physiological relevance -Complete organism -Test drug metabolism | -Species differences -Low throughput -Poor prediction -Ethical concerns -High costs |

| Renal Cell Types | Biomarkers | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein markers | m-RNA markers | ||

| Podocytes | Wilms tumor-1 Nephrin Podocin Podocalyxin Synaptopodin | NPHS1 NPHS2 Synaptopodin Wilms tumor-1 Podocalyxin | [18] [88] [89] [23] [90] |

| Proximal tubules | Lotus tetragonolobus lectin Aquaporin-1 (AQP1) Cadherin 6 Jagged 1 Megalin Kidney injury molecule 1 | ABCC1 ABCC3 ABCC4 SLC22A3 SLC40A1 | [18] [88] [89] |

| Loop of Henle | Cadherin 1 Uromodulin | Claudin 10 Claudin 14 SLC12A1 Uromodulin | [18] [91] [92] [89] |

| Distal tubules | Pterin-4 alpha-carbinolamine dehydratase 1 Solute carrier family 41 member 3; Cadherin 1 Brn1 Na+/Cl– cotransporter GATA Binding Protein 3 | Pterin-4 alpha-carbinolamine dehydratase 1 Solute carrier family 41 member 3; Cadherin 1 SLC12A3 Calbindin 1 | [18] [88] [89] |

| Collecting ducts | Dolichus biflorisagglutinin Aquaporin-2 (AQP2) Aquaporin-3 (AQP3) | Cadherin 1 GATA Binding Protein 3 Aquaporin-3 | [23] [89] |

| Endothelial cell | Platelet and endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 Cadherin 5 Fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 1 Cluster of differentiation 34 Cluster of differentiation 31 | Platelet and endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 Cadherin 5 Fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 1 CD34 | [23] [93] [89] [94] |

| Mesangial cells | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta Insulin like growth factor binding protein 5 Transgelin Matrix metallopeptidase 2 | Actin alpha 2, smooth muscle Collagen type I alpha 1 chain Transgelin | [23] [95] |

| Cell Types | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell lines: -HK2 -NKi-2 -ciPTEC -RPTEC/TERT1 | -A proximal tubular cell (PTC) line derived from normal kidney, immortalized by transduction with human papilloma virus 16 (HPV-16) E6/E7 genes -Act as a positive control -Stable cell line -Potentially valuable in toxicity and drug transporter assays -Stable cell line-Broad transporter and metabolic enzyme expression -Polarized tight monolayer formation-Potentially valuable in toxicity and drug transporter assays | -Limited transporter or proximal tubule characteristics -Low prediction -Limited data available for in vitro to in vivo extrapolation -Limited data available for in vitro to in vivo extrapolation | [113,114] [19] [115,116,117] |

| Human primary renal cells: -fetal renal cells -biopsy-derived renal cells | -Complete transporter and metabolic enzyme expression -Polarized tight monolayer formation. -High predictivity -Transepithelial transport -Broad range of biomarker assays available | -Expression of relevant proteins rapidly decreased -Limiting long-term exposure -Batch-to-batch variation -Limited availability | [81,118,119] |

| Human stem cells: -ESC -iPSC -USC | -In vivo-like complexity -In vivo-like architecture -Contains a variety of kidney cells, including proximal and distal renal tubular cells, endothelial cells, podocytes, and kidney-derived cells for high-throughput screening -Patient specific -Robust proliferative potential -Multipotential differentiation -Paracrine effects -Renal progenitor/stem cells -Obtained noninvasively at a less cost and simpler method | -Not free from ethical and legal issues -Immaturity -Mal-differentiation to non-renal cells Cultures are sometime contaminated when urine samples are obtained from female donors | [115,120] [115,121] [122,123,124] |

| Animal primary renal cells -Mouse -Rat -Rabbit Animal cell lines -Dog (MDCK) -Pig (LLC-PK1) -Monkey (VERO) | -Complete transporter and metabolic enzyme expression -Polarized tight monolayer formation -Transepithelial transport -Broad range of biomarker assays available -Stable cell line -Well established -Formation of polarized tight monolayer | -Species differences -Relatively low predictivity -Animal experiments -Species differences -Low predictivity | [125,126] [127,128,129] |

| Methods | Fabrication | Mechanism and Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditioned medium from renal cell culture | Matrigel–Stem Cells–Matrigel [23,86] | -Form a tubular structure, which contain proximal tubules, distal tubules, and podocytes -Simple steps and low cost | -More off-target differentiated cells |

| Co-culture with renal cells | Induce differentiation into iUB and iNP, and then co-culture the two kinds of cells with stromal cells in the same low-adhesion 96-well plate, and induce with RA, CHIR99021, and FGF9 [147] | -Similar to normal kidney -Mutual promotion of cell differentiation and maturation | -Inefficient |

| Renal ECM | One gram of ECM was mixed with 100 mg of pepsin from porcine gastric mucosa and sterilized by gamma irradiation (1 Mrad). The supernatant solution was neutralized with 0.1 N NaOH and stored at −80 °C [27,28] | -Its compositional, structural, and molecular similarity to human k-ECM -Available in large amounts | -Potential loss of soluble growth factors and cytokines during the decellularization process -Heterogeneous composition of the ECM from batch to batch |

| Growth factors: HGF FGF9 | Company name: PeproTech [18,149] R&D Systems [88] PeproTech [94] | -Precisely regulated to the post-intermediate mesoderm stage -Express Hoxd11 -Ensure differentiation into metanephric mesenchyme | -Immature renal unit -With no specific renal cell types |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, P.; Duan, Z.; Liu, S.; Pachon, I.; Ma, J.; Hemstreet, G.P.; Zhang, Y. Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Assessment in 3D Cellular Models. Micromachines 2022, 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13010003

Yu P, Duan Z, Liu S, Pachon I, Ma J, Hemstreet GP, Zhang Y. Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Assessment in 3D Cellular Models. Micromachines. 2022; 13(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Pengfei, Zhongping Duan, Shuang Liu, Ivan Pachon, Jianxing Ma, George P. Hemstreet, and Yuanyuan Zhang. 2022. "Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Assessment in 3D Cellular Models" Micromachines 13, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13010003

APA StyleYu, P., Duan, Z., Liu, S., Pachon, I., Ma, J., Hemstreet, G. P., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Assessment in 3D Cellular Models. Micromachines, 13(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13010003