Effect of Temperature on the Hydrotreatment of Sewage Sludge-Derived Pyrolysis Oil and Behavior of Ni-Based Catalyst

Abstract

:1. Introduction

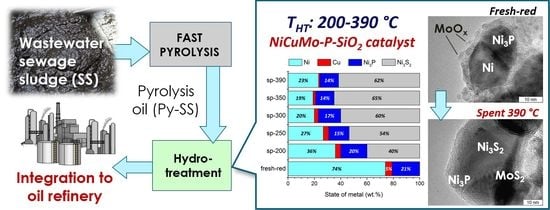

2. Results and Discussion

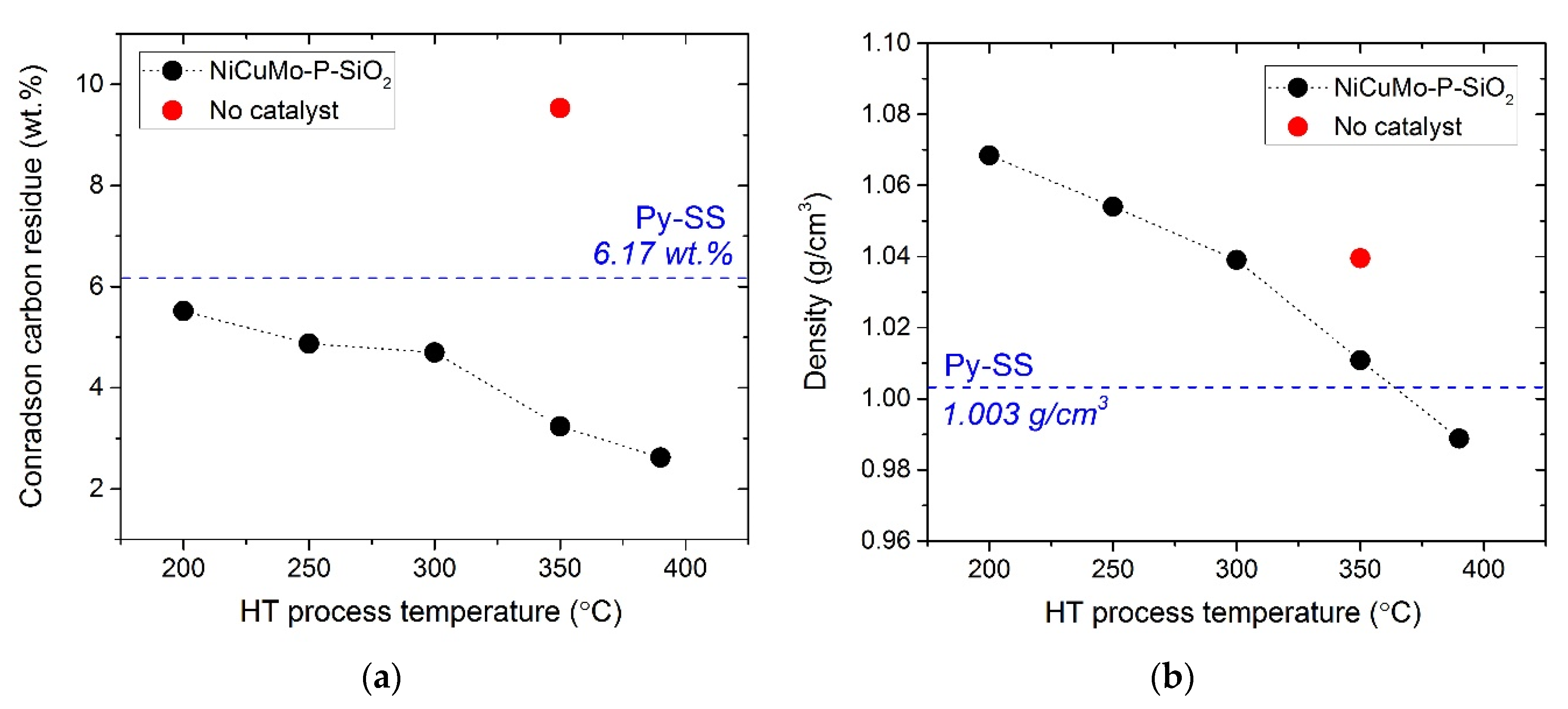

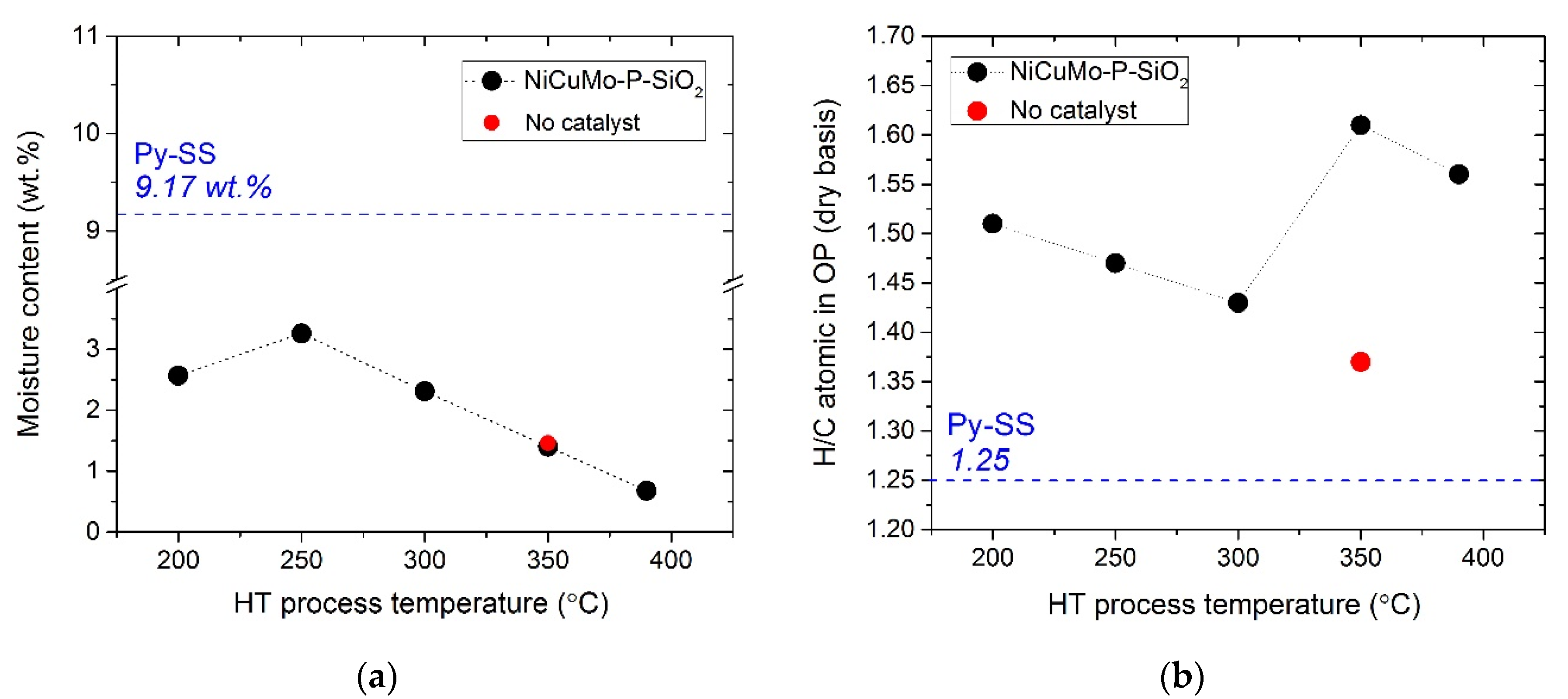

2.1. Hydrotreatment of Py-SS in a Batch Reactor

2.2. The Analysis of Reaction Products

2.3. Catalyst Characterization

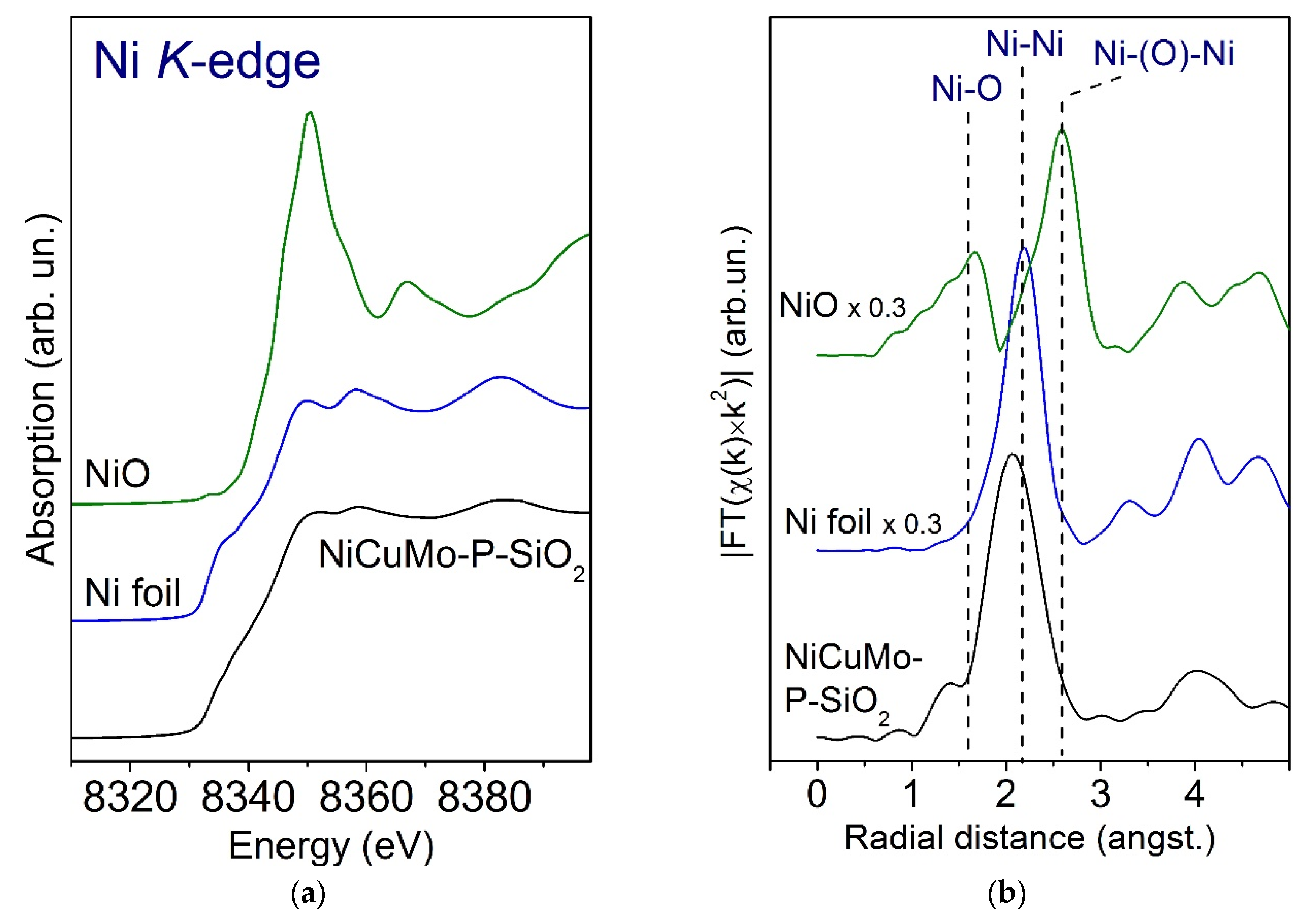

2.3.1. Fresh Catalyst

- Low-temperature region with a series of small peaks (150–350 °C) predominantly corresponds to the reduction of CuO and well crystallized NiO particles with a defective structure, weakly bonded with SiO2 [23].

- High-temperature region with one dominant peak corresponds to the reduction of oxide-silicate Ni forms, Mo6+ species into Mo4+, and the total reduction of Mo4+ into metallic Mo0 [23,52]. Moreover, the reduction of phosphate species occurs in this region as well because of the high thermal stability of the P–O bond [53].

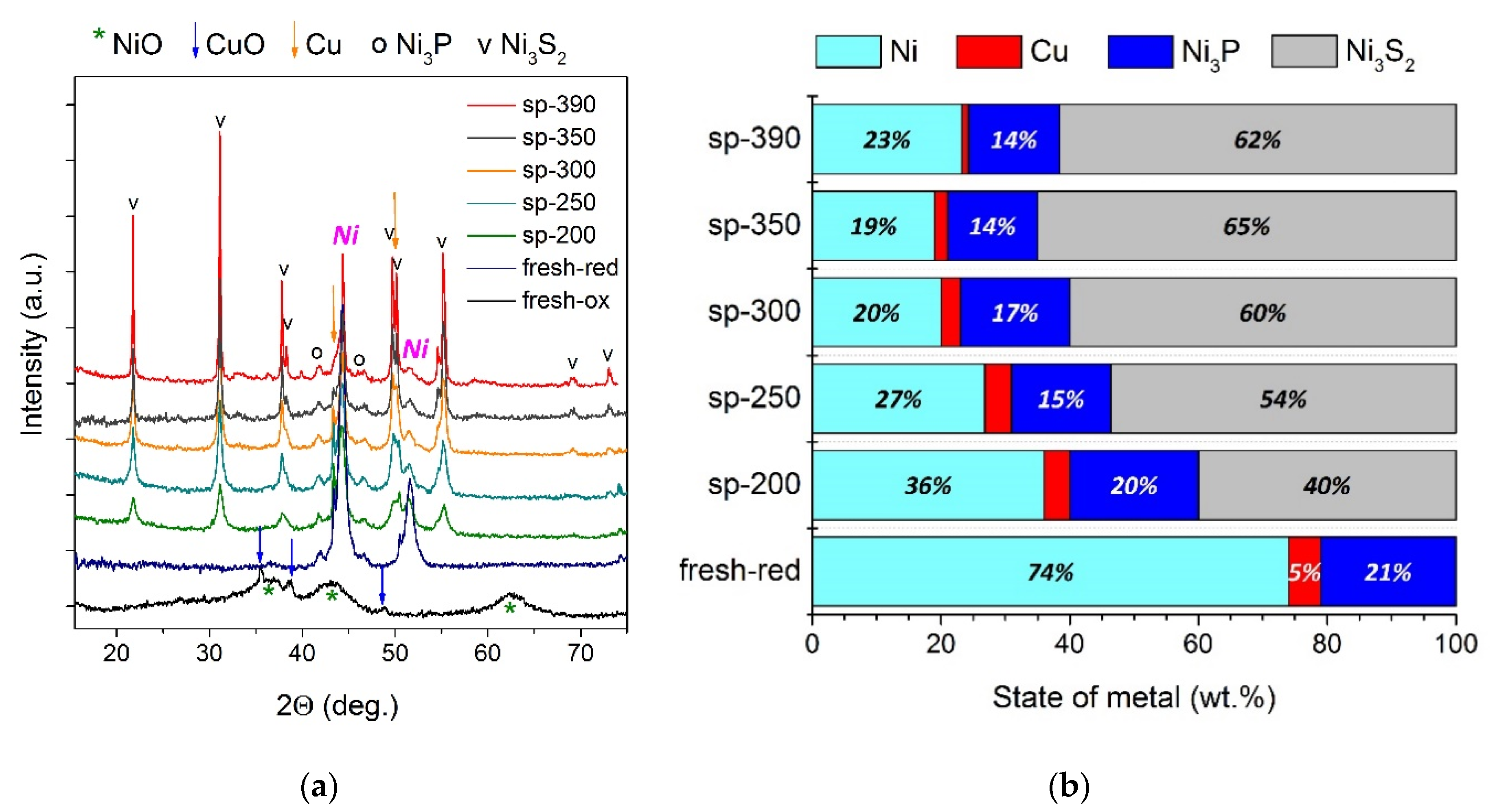

2.3.2. The Study of a Spent Catalyst after the Hydrotreatment of Py-SS

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Catalyst Preparation

3.3. Catalytic Hydrotreatment of Py-SS in a Batch Reactor

3.4. Analysis of Reaction Products

3.5. Catalyst Characterization

4. Conclusions

- The increase in the temperature of Py-SS hydrotreatment resulted in the increasing yield of gas-phase products along with the decreasing yield of coke deposits, very likely due to more intense decarboxy(carbony-)lation, hydrocracking, and hydrogenation.

- The decrease in water content, density, and CCR value of the hydrotreated product oils indicated that less polar and more thermally stable products were formed as a result of the catalytic hydrotreatment.

- As compared to the initial feed and non-catalytic processing, a higher H/C atomic ratio of product oils in the case of catalytic hydrotreatment evidenced the high hydrogenation ability of the NiCuMo-P-SiO2 catalyst.

- Severe temperature conditions promoted the conversion of long-chain fatty acids into n-alkanes, while the amount of volatile aromatic species (monoaromatic hydrocarbons, oxygen-containing aromatic hydrocarbons, and PAHs) increased via the hydroconversion of high molecular mass components.

- Active catalyst species comprised of Ni3P and metallic Ni-based solid solutions with possible incorporation of Cu and Mo were uniformly distributed throughout the amorphous silica matrix.

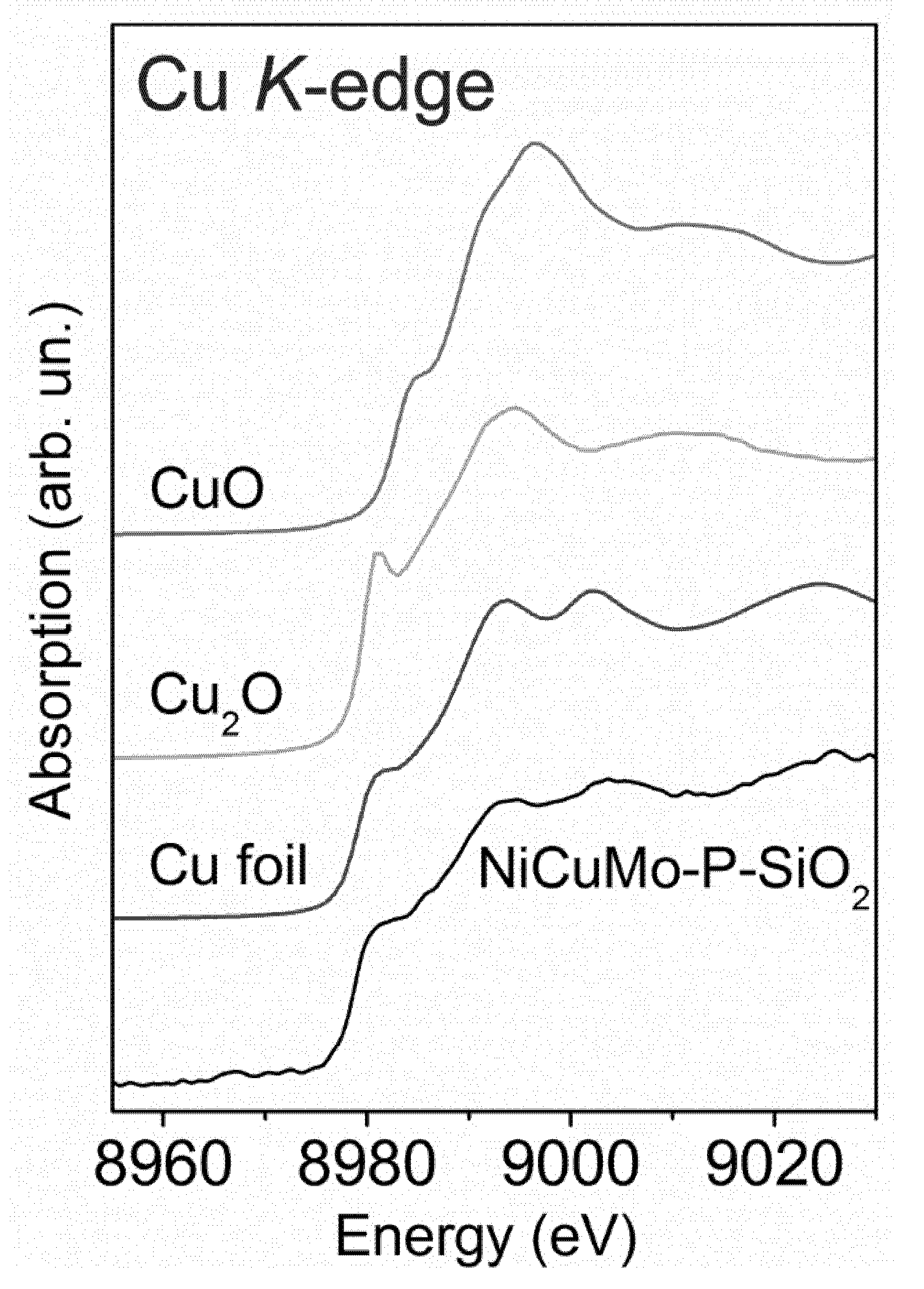

- Mo-oxidized species were in an amorphous or highly dispersed state in the fresh catalyst, while Cu was in a fully reduced metallic state.

- Initially amorphous Mo species were transformed into a MoS2 state in post-reaction catalysts; the MoS2 phase is known to be active in hydroprocessing.

- As the severity of the hydroprocessing increased, metallic Ni particles were transformed into sulfide state Ni3S2, whilst nickel phosphide species possessed outstanding stability in the whole temperature range, holding great promise for the upgrading of sewage sludge crude bio-oils.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raheem, A.; Sikarwar, V.S.; He, J.; Dastyar, W.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Wang, W.; Zhao, M. Opportunities and challenges in sustainable treatment and resource reuse of sewage sludge: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 616–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gisi, S.; Notarnicola, M. Industrial wastewater treatment. In Encyclopedia of Sustainable Technologies; Abraham, M.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kelessidis, A.; Stasinakis, A.S. Comparative study of the methods used for treatment and final disposal of sewage sludge in European countries. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, V.K.; Lo, S.-L. Sludge: A waste or renewable source for energy and resources recovery? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 708–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rulkens, W. Sewage Sludge as a biomass resource for the production of energy: Overview and assessment of the various options. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, H.D.; Werkneh, A.A.; Ambaye, T.G. Current updates on waste to energy (WtE) technologies: A review. Renew. Energy Focus 2018, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, E.; de Andrés, J.M.; Narros, A.; Rodríguez, M.E. Air and air-steam gasification of sewage sludge. The influence of dolomite and throughput in tar production and composition. Fuel 2014, 115, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xiong, S.; Xiao, B.; Yu, D.; Jia, X. Mechanism of wet sewage sludge pyrolysis in a tubular furnace. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manara, P.; Zabaniotou, A. Towards sewage sludge based biofuels via thermochemical conversion—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2566–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnaudeau, V.; Dignac, M.-F. The organic matter composition of various wastewater sludges and their neutral detergent fractions as revealed by pyrolysis-GC/MS. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2007, 78, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, J.; Charles, U.; Steele, P.H. Pyrolysis of wood/biomass for bio-oil: A critical review. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 848–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, S.; Cao, Y.; Liang, P.; Zhang, J.; Wong, M.H.; Wang, M.; Shan, S.; et al. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on properties and environmental safety of heavy metals in biochars derived from municipal sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 320, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samolada, M.C.; Zabaniotou, A.A. Comparative assessment of municipal sewage sludge incineration, gasification and pyrolysis for a sustainable sludge-to-energy management in Greece. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrone, P.A.; Elliott, D.C.; Billing, J.M.; Hallen, R.T.; Hart, T.R.; Kadota, P.; Moeller, J.C.; Randel, M.A.; Schmidt, A.J. Bench-scale evaluation of hydrothermal processing technology for conversion of wastewater solids to fuels. Water Environ. Res. 2018, 90, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, D.; Haider, M.S.; Rosendahl, L.A. Catalytic upgrading of hydrothermal liquefaction biocrudes: Different challenges for different feedstocks. Renew. Energy 2019, 141, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.-j.; Yuan, X.-z.; Zhu, H.-n.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.-l.; Zeng, G.-m. Comparative studies of thermochemical liquefaction characteristics of microalgae, lignocellulosic biomass and sewage sludge. Energy 2013, 56, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonts, I.; Gea, G.; Azuara, M.; Ábrego, J.; Arauzo, J. Sewage sludge pyrolysis for liquid production: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2781–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.-P.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Morishita, K.; Wei, X.-Y.; Takarada, T. Fractionation and identification of organic nitrogen species from bio-oil produced by fast pyrolysis of sewage sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 7648–7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazo, R.O.; de Luna, M.D.G.; Capareda, S.C. Assessing biodiesel production from sewage sludge-derived bio-oil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhar, S.; Uehara, S.; Yoshida, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Morioka, T.; Nagai, M. Hydrodenitrogenation of fast pyrolysis bio-oil derived from sewage sludge on NiMo/Al2O3 sulfide catalyst. Fuel Process. Technol. 2012, 101, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiyanti, A.R.; Bykova, M.V.; Khromova, S.A.; Yin, W.; Venderbosch, R.H.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Heeres, H.J. Ni-based catalysts for the hydrotreatment of fast pyrolysis oil. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, M.V.; Otyuskaya, D.S.; Rekhtina, M.A.; Bulavchenko, O.A.; Stonkus, O.A.; Kaichev, V.V.; Zavarukhin, S.G.; Thybaut, J.W.; Alexiadis, V.; Venderbosch, R.H.; et al. NiCuMo-SiO2 catalyst for pyrolysis oil upgrading: Model acidic treatment study. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 573, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykova, M.V.; Ermakov, D.Y.; Khromova, S.A.; Smirnov, A.A.; Lebedev, M.Y.; Yakovlev, V.A. Stabilized Ni-based catalysts for bio-oil hydrotreatment: Reactivity studies using guaiacol. Catal. Today 2014, 220–222, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Venderbosch, R.H.; Alekseeva, M.V.; Figueirêdo, M.B.; Heeres, H.; Khromova, S.A.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Cannilla, C.; Bonura, G.; Frusteri, F.; et al. Hydrotreatment of the carbohydrate-rich fraction of pyrolysis liquids using bimetallic Ni based catalyst: Catalyst activity and product property relations. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 169, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, V.A.; Khromova, S.A.; Sherstyuk, O.V.; Dundich, V.O.; Ermakov, D.Y.; Novopashina, V.M.; Lebedev, M.Y.; Bulavchenko, O.; Parmon, V.N. Development of new catalytic systems for upgraded bio-fuels production from bio-crude-oil and biodiesel. Catal. Today 2009, 144, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, M.V.; Rekhtina, M.A.; Lebedev, M.Y.; Zavarukhin, S.G.; Kaichev, V.V.; Venderbosch, R.H.; Yakovlev, V.A. Hydrotreatment of 2-methoxyphenol over high Ni-loaded sol-gel catalysts: The influence of Mo on catalyst activity and reaction pathways. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 5153–5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.; Xie, C.; Liu, D.; Liu, S.; Zhao, R.; Bian, B. Preparation and characterization of petroleum-based mesophase pitch by thermal condensation with in-process hydrogenation. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 30230–30238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menoufy, M.F.; Ahmed, H.S.; Betiha, M.A.; Sayed, M.A. A comparative study on hydrocracking and hydrovisbreaking combination for heavy vacuum residue conversion. Fuel 2014, 119, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.A.; Alekseeva, M.V.; Bulavchenko, O.A.; Yakovlev, V.A. Studying the effect of the process temperature on the degree of bio-oil hydrotreatment at low hydrogen contents over NiCu-SiO2 catalyst with a high metal loading. Catal. Ind. 2019, 11, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, P.; Sharma, B.K.; Kunwar, B.; Ross, A.B. Hydroprocessing of bio-crude from continuous hydrothermal liquefaction of microalgae. Fuel 2015, 159, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunwar, B.; Deilami, S.D.; Macaskie, L.E.; Wood, J.; Biller, P.; Sharma, B.K. Nanoparticles of Pd supported on bacterial biomass for hydroprocessing crude bio-oil. Fuel 2017, 209, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Savage, P.E. Feedstocks for fuels and chemicals from algae: Treatment of crude bio-oil over HZSM-5. Algal Res. 2013, 2, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussis, S.G.; Cranford, R.; Sytkovetskiy, N. Thermal treatment of crude algae oils prepared under hydrothermal extraction conditions. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 5294–5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiyanti, A.R.; Gutierrez, A.; Honkela, M.L.; Krause, A.O.I.; Heeres, H.J. Hydrotreatment of wood-based pyrolysis oil using zirconia-supported mono and bimetallic (Pt, Pd, Rh) catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2011, 407, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.E.; Menéndez, J.A.; Domínguez, A.; Pis, J.J.; Martínez, O.; Calvo, L.F.; Bernad, P.L. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on the composition of the oils obtained from sewage sludge. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A. Pressurized pyrolysis of sewage sludge: Process performance and products characterization. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 139, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domınguez, A.; Menéndez, J.A.; Inguanzo, M.; Bernad, P.L.; Pis, J.J. Gas chromatographic–mass spectrometric study of the oil fractions produced by microwave-assisted pyrolysis of different sewage sludges. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 1012, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Yu, Y.; Huang, H. Temperature influence and distribution of bio-oil from pyrolysis of granular sewage sludge. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 130, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindarom, C.; Meeyoo, V.; Rirksomboon, T.; Rangsunvigit, P. Thermochemical decomposition of sewage sludge in CO2 and N2 atmosphere. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Guo, Y.; Peng, N.; Lang, Q.; Xia, Y.; Gai, C.; Liu, Z. Nitrogen transformation among char, tar and gas during pyrolysis of sewage sludge and corresponding hydrochar. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 126, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazo, R.O.; Genuino, D.A.D.; de Luna, M.D.G.; Capareda, S.C. Bio-oil production from dry sewage sludge by fast pyrolysis in an electrically-heated fluidized bed reactor. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2017, 27, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boocock, D.G.B.; Konar, S.K.; Mackay, A.; Cheung, P.T.C.; Liu, J. Fuels and chemicals from sewage sludge: 2. The production of alkanes and alkenes by the pyrolysis of triglycerides over activated alumina. Fuel 1992, 71, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonts, I.; Azuara, M.; Gea, G.; Murillo, M.B. Study of the pyrolysis liquids obtained from different sewage sludge. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2009, 85, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonts, I.; Azuara, M.; Lázaro, L.; Gea, G.; Murillo, M.B. Gas chromatography study of sewage sludge pyrolysis liquids obtained at different operational conditions in a fluidized bed. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 5907–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, V.A.; Vuthaluru, H.B.; Bastow, T. Investigations into the control of odour and viscosity of biomass oil derived from pyrolysis of sewage sludge. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashkov, M.V.; Sidelnikov, V.N.; Bratchikova, A.A. New stationary ionic liquid phases with quinolinium cations for capillary gas chromatography. Anal. Lett. 2020, 53, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Jiang, X.; Lv, G.; Ma, X.; Jin, Y.; Wang, F.; Chi, Y.; Yan, J. Investigation into particle size influence on PAH formation during dry sewage sludge pyrolysis: TG-FTIR analysis and batch scale research. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 112, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Arango, A.; Fonts, I.; Chejne, F.; Arauzo, J. Product compositions from sewage sludge pyrolysis in a fluidized bed and correlations with temperature. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2016, 121, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypres, R. Aromatic hydrocarbons formation during coal pyrolysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 1987, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.-J.; Li, B.-Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.-Z. Formation of NOx precursors during the pyrolysis of coal and biomass. Part, V. Pyrolysis of a sewage sludge. Fuel 2002, 81, 2203–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakova, M.A.; Ermakov, D.Y. High-loaded nickel-silica catalysts for hydrogenation, prepared by sol-gel Route: Structure and catalytic behavior. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 245, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykova, M.V.; Ermakov, D.Y.; Kaichev, V.V.; Bulavchenko, O.A.; Saraev, A.A.; Lebedev, M.Y.; Yakovlev, V.A. Ni-based sol-gel catalysts as promising systems for crude bio-oil upgrading: Guaiacol hydrodeoxygenation study. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 113–114, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzaniuk, V.; Prins, R. Synthesis and characterization of silica-supported transition-metal phosphides as HDN catalysts. J. Catal. 2003, 219, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.P.; Proctor, A.; Hercules, D.M. Curve fitting analysis of ESCA Ni 2p spectra of nickel-oxygen compounds and Ni/Al2O3 catalysts. Appl. Spectrosc. 1984, 38, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöllner, A.; Lange, F.; Schmelz, H.; Knözinger, H. Characterization of mixed copper-manganese oxides supported on titania catalysts for selective oxidation of ammonia. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1993, 94, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Kloekhorst, A.; Venderbosch, R.H.; Bykova, M.V.; Khromova, S.A.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Heeres, H.J. Catalytic hydrotreatment of fast pyrolysis liquids in batch and continuous set-ups using a bimetallic Ni-Cu catalyst with a high metal content. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 5899–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bianchi, C.L.; Cattania, M.G.; Villa, P. XPS characterization of Ni and Mo oxides before and after “in situ” treatments. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1993, 70–71, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCanio, S.J.; Cataldo, M.C.; DeCanio, E.C.; Storm, D.A. Evidence from XPS for the stabilization of high-valent molybdenum by addition of potassium in MoAl2O3 catalysts. J. Catal. 1989, 119, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtayries, A.; Wisniewski, S.; Grimblot, J. Formation of thin oxide and sulphide films on polycrystalline molybdenum foils: Characterization by XPS and surface potential variations. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1997, 87, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, C.-O.A.; Mathieu, H.-J.; Landolt, D. Angle-resolved XPS analysis of molybdenum and tungsten in passive films on stainless steel PVD alloys. Surf. Interface Anal. 2002, 34, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Óvári, L.; Kiss, J.; Farkas, A.P.; Solymosi, F. Surface and Subsurface Oxidation of Mo2C/Mo(100): Low-energy ion-scattering, aAuger electron, angle-resolved X-ray photoelectron, and mass spectroscopy studies. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 4638–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Z. Mechanical mixtures of metal oxides and phosphorus pentoxide as novel precursors for the synthesis of transition-metal phosphides. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, A.W.; Gaudette, A.F.; Bussell, M.E. Hydrodesulfurization properties of cobalt-nickel phosphide catalysts: Ni-rich materials are highly active. J. Catal. 2008, 260, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, J.A.; Burr, A.F. Reevaluation of X-ray atomic energy levels. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1967, 39, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochet, A.; Baubet, B.; Moizan, V.; Devers, E.; Hugon, A.; Pichon, C.; Payen, E.; Briois, V. Influence of the preparation conditions of oxidic NiMo/Al2O3 catalysts on the sulfidation ability: A quick-XAS and Raman spectroscopic study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 23928–23942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, I.; Soriano, L.; Diaz-Fernandez, D.; Dominguez-Canizares, G.; Gutierrez, A.; Castro, G.R.; Chaboy, J. X-ray absorption study of the local structure at the NiO/oxide interfaces. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 2013, 20, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaur, A.; Shrivastava, B.D.; Joshi, S.K. Copper K-edge XANES of Cu(I) and Cu(II) oxide mixtures. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2009, 190, 012084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, H. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1969, 2, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscagli, C.; Yang, C.; Welle, A.; Wang, W.; Behrens, S.; Raffelt, K.; Grunwaldt, J.-D. Effect of pyrolysis oil components on the activity and selectivity of nickel-based catalysts during hydrotreatment. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 544, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, P.M.; Gardini, D.; de Carvalho, H.W.P.; Damsgaard, C.D.; Grunwaldt, J.-D.; Jensen, P.A.; Wagner, J.B.; Jensen, A.D. Stability and resistance of nickel catalysts for hydrodeoxygenation: Carbon deposition and effects of sulfur, potassium, and chlorine in the feed. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 3672. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev, V.A.; Khromova, S.A.; Ermakov, D.Y. Catalyst and Process for Hydrodeoxygenation of Oxygen-Organic Products of Plant Biomass. Processing. Patent RU2440847, 27 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Déniel, M.; Haarlemmer, G.; Roubaud, A.; Weiss-Hortala, E.; Fages, J. Energy valorisation of food processing residues and model compounds by hydrothermal liquefaction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1632–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliott, D.C.; Biller, P.; Ross, A.B.; Schmidt, A.J.; Jones, S.B. Hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass: Developments from batch to continuous process. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 178, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gollakota, A.R.K.; Kishore, N.; Gu, S. A review on hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1378–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Analysis | Parameter | Analytical Method | As-Received Wet Basis | Dry Matter Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimate analysis, wt. % | C | Elemental analysis | 66.8 | 73.5 |

| H | Elemental analysis | 8.0 | 7.7 | |

| O | By difference | 20.8 | 13.9 | |

| N | Elemental analysis | 4.0 | 4.4 | |

| S | XRF-S analysis | 0.43 | 0.47 | |

| Proximate analysis | Water content, wt. % | KF Titration | 9.17 | - |

| Density, g/cm3 | ASTM D 4052 | 1.003 | - | |

| Conradson carbon residue (CCR), wt. % | ASTM D 189 | 6.17 | - |

| Reaction Temperature | 200 °C | 250 °C | 300 °C | 350 °C | 350 °C—No Cat | 390 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed (H2 consumed + Py-SS), g | 60.49 | 60.55 | 60.69 | 60.87 | 60.47 | 60.99 |

| Yield (wet basis), wt. % of feed: | ||||||

| Organic-rich phase (OP) | 85.6 | 85.6 | 81.9 | 81.3 | 79.1 | 75.8 |

| Aqueous phase (AP) | 6.6 | 6.4 | 8.7 | 12.5 | 11.4 | 14.3 |

| Coke on the catalyst | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 1 | 0.3 |

| Gas phase (GP) | 1.6 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 6.7 |

| CH4 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 1.19 |

| CO2 | 1.51 | 1.64 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 3.51 | 4.16 |

| CO | - | - | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.44 |

| Light HCs (C2–C4) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.91 |

| Mass balance, wt. % | 94.3 | 94.3 | 94.2 | 97.9 | 95.3 | 97.1 |

| Organic Sample Dry Matter, wt. % | OP-200 | OP-250 | OP-300 | OP-350 | OP-390 | OP-350 No Cat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C 1 | 75.7 | 76.2 | 76.8 | 79.1 | 81.6 | 81.2 |

| H 1 | 9.6 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 9.3 |

| O 2 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 10.7 | 7.8 | 5.7 | 6.5 |

| N 1 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.7 |

| S 3 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.34 |

| Compound | Py-SS Peak Area, % (Peak No., Figure S1A) | OP-350 Peak Area, % (Peak No., Figure S1B) | OP-390 Peak Area, % (Peak No., Figure S1C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoaromatic compounds | |||

| Benzene, ethyl- | - | - | 1.76 (1) |

| Benzene, 1,2-dimethyl- | 0.74 (1) | - | 1.21 (2) |

| Benzene, 1,4-dimethyl- | - | 0.55 (1) | - |

| Benzene, n-propyl- | - | 0.68 (3) | 0.88 (4) |

| Benzene, (1-methylethyl)- | - | 0.48 (4) | - |

| Benzene, 1-ethyl-4-methyl- | - | - | 0.9 (5) |

| Benzene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- | - | 1.67 (5) | 2.56 (6) |

| Benzene, 1-ethyl-2-methyl- | 0.46 (3) | - | 0.24 (7) |

| Benzene, 1-ethyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- | - | - | 1.0 (9) |

| Benzene, 1-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)- | 0.42 (4) | - | - |

| Benzene, 1,2,4-trimethyl- | - | 0.27 (9) | 0.92 (10) |

| Benzene, 1-methyl-4-propyl- | - | - | 0.08 (11) |

| 1H-Indene, 2,3-dihydro- | - | 0.26 (11) | 0.37 (12) |

| Benzene, 1-butenyl- | 0.48 (8) | - | - |

| Benzene, n-pentyl- | - | 0.5 (13) | 0.34 (14) |

| 1H-Indene, 2,3-dihydro-4-methyl- | - | - | 0.24 (17) |

| Benzene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methyl-2-propenyl)- | - | - | 0.22 (18) |

| Benzene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)- | - | - | 0.96 (19) |

| 1H-Indene, 2,3-dihydro-1,6-dimethyl- | - | - | 0.21 (20) |

| Benzene, 2-ethyl-1,4-dimethyl- | - | - | 0.36 (21) |

| Benzene, 1-methyl-2-(2-propenyl)- | - | 0.27 (16) | - |

| 1H-Indene, 2,3-dihydro-4,7-dimethyl- | - | 0.25 (17) | - |

| Benzene, 2-ethenyl-1,3,5-trimethyl- | - | - | 0.56 (25) |

| 1H-Indene, 2,3-dihydro-1,1,5-trimethyl- | - | - | 0.54 (29) |

| Monoaromatics total area, % | 2.1 | 4.93 | 13.35 |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) | |||

| Naphthalene, 1-methyl- | - | 0.16 (43) | 0.18 (39) |

| Phenanthrene, 1-methyl-7-(1-methylethyl)- | 0.53 (74) | 0.69 (80) | 1.15 (76) |

| PAHs total area, % | 0.53 | 0.85 | 1.33 |

| O-aromatic compounds | |||

| Phenol, 2,6-dimethyl- | 0.31 (18) | 0.45 (34) | 0.61 (30) |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy- | 2.71 (20) | - | - |

| Phenol | 1.52 (21) | 3.4 (37) | 4.16 (32) |

| Phenol, 2-methyl- | 1.17 (22) | 1.8 (38) | 2.78 (33) |

| Phenol, 2,3-dimethyl- | - | 0.77 (40) | 1.53 (35) |

| Phenol, 2,5-dimethyl- | 0.49 (24) | - | - |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-methyl- | 5.29 (25) | - | - |

| Phenol, 2,5-diethyl- | - | - | 0.28 (36) |

| Phenol, 4-methyl- | 1.31 (26) | 5.64 (41) | 4.91 (37) |

| Phenol, 3-methyl- | - | 4.34 (42) | 7.32 (38) |

| Phenol, 2,3,5-trimethyl- | - | 0.56 (44) | 0.84 (40) |

| Phenol, 2-ethyl-5-methyl- | - | 1.04 (46) | 1.52 (42) |

| Phenol, 4-ethyl-2-methoxy- | 2.11 (29) | - | - |

| Phenol, 2-ethyl- | 0.61 (30) | - | - |

| Phenol, 4-ethyl- | 0.03 (32) | 3.08 (47) | 2.58 (43) |

| Phenol, 3-ethyl- | - | 1.7 (48) | 2.56 (44) |

| Phenol, 4-(1-methylpropyl)- | - | 0.23 (49) | 0.35 (45) |

| Phenol, 3,4-dimethyl- | - | 1.03 (50) | 1.25 (46) |

| Phenol, 2-(1-methylpropyl)- | - | 0.68 (51) | 0.9 (47) |

| Phenol, 4-propyl- | - | 3.18 (52) | 3.03 (48) |

| Phenol, 3-propyl- | - | 2.05 (53) | 3.71 (49) |

| Phenol, 3,4,5-trimethyl- | - | 0.56 (55) | 1.32 (51) |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-propyl- | 1.1 (33) | - | - |

| Ethanone, 1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)- | - | - | 1.45 (53) |

| Phenol, 4-(3-hydroxyprop-1-en-1-yl) | - | 0.61 (58) | 2.1 (54) |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-(1-propenyl)- | 0.99 (36) | - | - |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-vinyl- | 0.52 (39) | - | - |

| Phenol, 4-(2-propenyl)- | - | 0.61 (62) | 0.42 (57) |

| Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-(2-propenyl)- | 2.54 (46 | - | - |

| Phenol, 2,6-dimethoxy- | 1.04 (47) | - | - |

| 1,2-Benzenediol | 0.69 (49) | - | - |

| 1,4-Benzenediol | 0.58 (51) | - | - |

| Phenol, 2,6-dimethoxy-4-(2-propenyl)- | 0.32 (58) | - | - |

| Oxy-aromatics total area, % | 23.33 | 31.73 | 43.62 |

| Alkanes | |||

| n-Tridecane | - | - | 0.47 (3) |

| n-Tetradecane | - | - | 0.37 (8) |

| n-Pentadecane | - | - | 2.32 (16) |

| n-Heptadecane | - | - | 4.92 (23) |

| Alkanes total area, % | - | - | 8.08 |

| Acids | |||

| Ethanoic acid (acetic acid) | 1.51 (2) | 1.32 (2) | - |

| Propanoic acid | 0.49 (5) | 0.48 (6) | - |

| Butanoic acid | - | 3.01 (12) | 2.08 (13) |

| 2-Butenoic acid, (E)-(crotonic acid) | 0.4 (10) | - | - |

| Butanoic acid, 3-methyl- | - | 0.57 (15) | 0.46 (15) |

| Pentanoic acid | - | 0.8 (18) | - |

| Pentanoic acid, 4-methyl- | - | 0.51 (23) | - |

| Hexanoic acid | - | 0.45 (24) | - |

| Heptanoic acid | - | 0.42 (29) | - |

| Dodecanoic acid | 0.15 (37) | - | - |

| Tetradecanoic acid | 0.97 (45) | - | - |

| Hexadecanoic acid (palmitic acid) | 11.49 (53) | 10.69 (67) | 6.16 (63) |

| 9-Hexadecenoic acid (palmitoleic acid) | 1.81 (54) | - | - |

| Octadecanoic acid (stearic acid) | 6.83 (59) | 7.33 (70) | 3.73 (66) |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-(oleic acid) | 10.55 (60) | 3.49 (71) | 3.29 (67) |

| 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-(linoleic acid) | 6.05 (63) | 6.09 (72) | 1.05 (68) |

| Eicosanoic acid | 1.56 (65) | - | - |

| Docosanoic acid | - | 1.87 (75) | 0.66 (70) |

| Acids total area, % | 41.81 | 37.03 | 17.43 |

| Fatty acids methyl esters (FAMEs) | |||

| 5,9-docosadienoic acid, methyl ester | 0.48 (27) | - | - |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 0.94 (35) | - | - |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester | 0.91 (44) | - | - |

| FAMEs total area, % | 2.33 | - | - |

| Polycyclic compounds | |||

| 1-Isopropyl-4,7-dimethyl- 1,2,4a,5,6,8a-hexahydronaphthalene | 0.88 (12) | - | - |

| Naphthalene, 6-ethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro- | - | 0.22 (27) | 1.3 (24) |

| Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro- 1,6-dimethyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- | - | 0.54 (31) | 0.5 (28) |

| 18-Norabieta-8,11,13-triene | 0.46 (38) | 0.5 (60) | - |

| Abieta-8,11,13-trien-18-al | 0.38 (41) | - | 2.89 (55) |

| Tetrahydroabietic acid | - | 3.26 (77) | 0.52 (74) |

| Dihydroabietic acid | - | 0.68 (78) | - |

| Dehydroabietic acid | 2.27 (75) | 2.86 (83) | 0.28 (79) |

| Polycyclic compounds area, % | 3.99 | 8.06 | 5.49 |

| Other oxygenated compounds | |||

| 1,2-Cyclopentanediol, 3-methyl- | - | 0.83 (7) | - |

| n-Decanal | 0.4 (11) | - | - |

| 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2,3-dimethyl- | 0.43 (15) | - | - |

| 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-3-methyl- | 1.25 (16) | - | - |

| 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy- | 0.24 (19) | - | - |

| Benzoic acid | 0.53 (34) | - | - |

| 7-Tetradecen-1-ol | 0.87 (64) | - | - |

| Total area, % | 3.72 | 0.83 | - |

| N-heteroaromatic compounds | |||

| 1H-Indole, 6-methyl- | - | 0.27 (68) | 0.49 (64) |

| 1H-Indole, 5,7-dimethyl- | - | 0.13 (69) | 0.24 (65) |

| Total area, % | - | 0.4 | 0.73 |

| Total identified peaks, % area | 77.81 | 83.33 | 90.03 |

| Sample | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiCuMo-P-SiO2-R 1 | 0.34 | 0.0047 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.014 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 2.04 | |

| Spectrum | Ni2p3/2 | Cu2p3/2 | Mo3d5/2 | P2p | |||||

| Charge state (atom. %) | Ni0 (100) | Cu0 (100) | Mo0 (10) | Mo4+ (75) | Mo5+ (15) | Pδ− (60) | P5+ (40) | ||

| Binding energy, eV | 852.6 | 932.3 | 227.9 | 229.2 | 231.6 | 129.5 | 134.5 | ||

| Catalyst Sample | Sp-200 | Sp-250 | Sp-300 | Sp-350 | Sp-390 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S wt. % | 7.1 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 13.2 | 13.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alekseeva, M.V.; Bulavchenko, O.A.; Saraev, A.A.; Kremneva, A.M.; Shashkov, M.V.; Zaikina, O.O.; Gulyaeva, Y.K.; Grachev, A.N.; Kikhtyanin, O.; Kubička, D.; et al. Effect of Temperature on the Hydrotreatment of Sewage Sludge-Derived Pyrolysis Oil and Behavior of Ni-Based Catalyst. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10111273

Alekseeva MV, Bulavchenko OA, Saraev AA, Kremneva AM, Shashkov MV, Zaikina OO, Gulyaeva YK, Grachev AN, Kikhtyanin O, Kubička D, et al. Effect of Temperature on the Hydrotreatment of Sewage Sludge-Derived Pyrolysis Oil and Behavior of Ni-Based Catalyst. Catalysts. 2020; 10(11):1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10111273

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlekseeva (Bykova), Maria V., Olga A. Bulavchenko, Andrey A. Saraev, Anna M. Kremneva, Mikhail V. Shashkov, Olesya O. Zaikina, Yuliya K. Gulyaeva, Andrey N. Grachev, Oleg Kikhtyanin, David Kubička, and et al. 2020. "Effect of Temperature on the Hydrotreatment of Sewage Sludge-Derived Pyrolysis Oil and Behavior of Ni-Based Catalyst" Catalysts 10, no. 11: 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10111273

APA StyleAlekseeva, M. V., Bulavchenko, O. A., Saraev, A. A., Kremneva, A. M., Shashkov, M. V., Zaikina, O. O., Gulyaeva, Y. K., Grachev, A. N., Kikhtyanin, O., Kubička, D., & Yakovlev, V. A. (2020). Effect of Temperature on the Hydrotreatment of Sewage Sludge-Derived Pyrolysis Oil and Behavior of Ni-Based Catalyst. Catalysts, 10(11), 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10111273