Generation of Free OHaq Radicals by Black Light Illumination of Degussa (Evonik) P25 TiO2 Aqueous Suspensions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Gamma Radiolysis

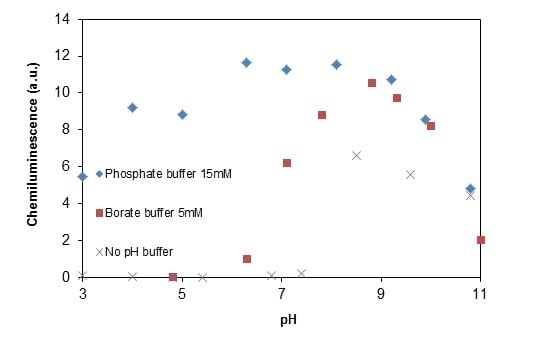

2.2. Photocatalysis

2.2.1. Adsorption of Phthalic Hydrazide to TiO2

2.2.2. Effects of Added Hydrogen Peroxide

| Item | PH | CLrate (a.u.) |

|---|---|---|

| A. No pH adjustment, 1 mM H2O2, 100 ppm TiO2, 50 μM PH | 4.6 | 0.853 |

| B. No pH adjustment, 1 mM H2O2, 50 μM PH | 6.1 | 0.255 |

| C. 1 mM HClO4, 1 mM H2O2, 100 ppm TiO2, 50 μM PH | 2.7 | 3.17 |

| D. 1 mM HClO4,1 mM H2O2, 50 μM PH | 2.7 | 0.324 |

| E. 1 mM HClO4, 100 ppm TiO2, 50 μM PH | 2.7 | 0.126 |

- Comparisons between items E, D and B show that a small yield of •OHaq can be obtained by photolysis of H2O2 at 365 nm. However, considering the absorbance of 365 nm UV light by TiO2 (~2.0 at 100 ppm), the contribution from direct photolysis of H2O2 can be neglected in the photocatalytic case;

- Comparisons between items E, C and A show that a significant yield of •OHaq can be obtained by reductive cleavage of H2O2 at 365 nm;

- Comparisons between items C and A show that of •OHaq by reductive cleavage of H2O2 at 365 nm depends on pH, and low pH promotes a higher yield. This trend is in accordance with the reaction suggested in Equation (3).

2.2.3. Effects of Br− as •OH Scavenger

2.2.4. Effects of Added Phosphate and Fluoride Anions

2.2.5. Formation of •OHaq Radicals

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials and Preparations

3.2. Irradiations

3.3. Chemiluminescence Measurements

. The total conversion of added phthalic hydrazide was controlled to be no more than 10%.

. The total conversion of added phthalic hydrazide was controlled to be no more than 10%.4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Ohtani, B. Photocatalysis A to Z - What we know and what we do not know in a scientific sense. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2010, 11, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshmiri, M.; Mohseni, M.; Troczynski, T. Development of a novel TiO2 sol-gel derived composite and its photocatalytic activities for trichloroethylene oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 2004, 53, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Agustina, T.E.; Ang, H.M.; Vareek, V.K. A review of synergistic effect of photocatalysis and ozonation of wastewater treatment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2005, 6, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malato, S.; Blanco, J.; Alarcon, D.C. Photocatalytic decontamination and disinfection of water with solar collectors. Catal. Today 2007, 122, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.S.; Ray, A.K. Major challenges in the design of a large-scale photocatalytic reactor for water treatment. Chem. Eng. Technol. 1999, 22, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, K.H.; Tao, R.; Kim, M.J. Use of a photocatalytic membrane reactor for the removal of natural organic matter in water. Effect of photoinduced desorption and ferrihydrite adsorption. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 322, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurum, D.C.; Agrios, A.G.; Gray, K.A.; Rajh, T.; Thurnauer, M.C. Explaning the enhanced photocatalytic activity of Degussa P25 mixed-phase TiO2 using EPR. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 4545–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, C.S.; Ollis, D.F. Photocatalytic degradation of organic water contaminants; mechanisms involving hydroxyl radical attack. J. Catal. 1990, 122, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Zhang, X.T.; Tryk, D.A. TiO2 photocatalysis and related surface phenomena. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2008, 63, 515–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, R.F.; Grätzel, M. EPR observation of trapped electrons in colloidal titanium dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. 1985, 89, 4495–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, D.; Ramsden, J.; Graetzel, M. Dynamics of interfacial electron-transfer processes in colloidal semiconductor systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 2977–2985. [Google Scholar]

- Spinks, J.W.T.; Woods, R.J. An Introduction to Radiation Chemistry, 3rd ed; John Wiley and Sons Inc: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Park, H.; Choi, W. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of NH3 to N2 on platinized TiO2 in water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 5462–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, R.; Imanishi, A.; Murakoshi, K.; Nakato, Y. In situ FTIR studies of primary intermediates of photocatalytic reactions on nanocrystalline TiO2 films in contact with aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 7443–7450. [Google Scholar]

- Micic, O.I.; Zhang, Y.; Cromack, K.R.; Trifunac, A.D.; Thurnauer, M.C. Trapped holes on titania colloids studied by electron paramagnetic resonans. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 7277–7283. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, Y.; Endo, K.; Ohta, I.; Nosaka, A.Y.; Nosaka, Y. Can OH radicals diffuse from the UV-irradiated photocatalytic TiO2 surfaces? Laser-induced fluorescence study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 11339–11346. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, A.; Hunte, S.L. An overview of semiconductor photocatalysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 1997, 108, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi, K.; Fujishima, A.; Watanabe, T.; Hashimoto, K. Quantum yields of active oxidative species formed on TiO2 photocatalyst. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2000, 134, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.; Czapski, G.; Rabani, J. Oxidation of phenol by radiolytically generated •OH and Chemically Generated SO4•−. A Distinction between •OH transfer and hole oxidation in in the photolysis of TiO2 colloid solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 6586–6591. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador, P. On the nature of photogenerated radical species active in the oxidative degradation of dissolved pollutants with TiO2 aqueous suspensions: A revision in the light of the electronic structure of adsorbed water. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 17038–17043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, D.; Serpone, N.; Meisel, D. Role of hydroxyl radicals and trapped holes in photocatalysis. A pulse radiolysis study. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 5166–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenländer, T. Photochemical Purification of Water and Air; WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.: Weinheim, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Bolton, J.R. Determination of the quantum yield for the photochemical generation of hydroxyl radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 4127–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesen, V.; Jonsson, M.J. Tris(hydroxymetyl) aminomethane as a probe in heterogeneous TiO2 photocatalysis. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2012, 15, 392–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi, K.; Fujishima, A.; Watanabe, T.; Hashimoto, K. Detection of active oxidative species in TiO2 photocatalysis using the fluorescence technique. Electrochem. Commun. 2000, 2, 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, T.; Nosaka, Y. Properties of O2•− and OH• formed in TiO2 aqueous suspensions by photocatalytic reaction and the influence of H2O2 and Some Ions. Langmuir 2002, 18, 3247–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, Y.; Komori, S.; Yawata, K.; Hirakawa, T.; Nosaka, A.Y. Photocatalytic OH Radical Formation in TiO2 aqueous suspension studied by several detection methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 4731–4735. [Google Scholar]

- Reitberger, T.; Gierer, J. Chemiluminescence as a means to study the role of hydroxyl radicals in oxidative processes. Holzforschung 1988, 42, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backa, S.; Jansbo, K.; Reitberger, T. Detection of hydroxyl radicals by a chemiluminescence method—A critical review. Holzforschung 1997, 51, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierer, J.; Jansbo, K.; Reitberger, T. Formation of hydroxyl radicals from hydrogen peroxide and their effect on bleaching of mechanical pulps. J. Wood Chem. Tech. 1993, 13, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backa, S.; Brolin, A. Determination of pulp characteristics by diffuse reflectance FTIR. Tappi J. 1991, 74, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Backa, S.; Gierer, J.; Reitberger, T.; Nilsson, T. Hydroxyl radical activity associated with the growth of white-rot fungi. Holzforschung 1993, 47, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.J.; Rose, A.L.; Waite, T.D. Phthalhydrazide chemiluminescence method for determination of hydroxyl radical production: Modifications and adaptations for use in natural systems. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Pan, X.; Rahmann, A.; Schuchmann, H.-P.; von Sonntag, A.C. Reversibility in the reaction of cyclohexadienyl radicals with oxygen in aqueous solution. Chem. Eur. J. 1995, 1, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielski, B.H.J.; Cabelli, D.E.; Arudi, R.L.; Ross, A.B. Reactivity of HO2/O2− radicals in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1985, 14, 1041–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, M.; Lind, J.; Reitberger, T.; Eriksen, T.E.; Merényi, G. Free radical combination reactions involving phenoxyl radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 8229–8233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, C.H.D.K.; Pearman, F.H. Chemiluminescent organic compounds. Part II the effect of substituents on the closure of phthalhydrizides to 5- and 6-membered rings. J. Chem. Soc. 1937, 64, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser, D.; Fahr, K.; Karl, W.; Wetzstein, H.-G. Hydroxylated metabolites of 2,4-dichlorophenol imply fenton-type reaction in Gloeophyllum striatum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 2479–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lide, D.R.; Frederiksen, H.P.R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 76th ed; CRC Press Inc.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wardman, P. Reduction potentials of one-electron couples involving free radicals in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1989, 18, 1637–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, M.S.; Mulac, W.A.; Weeks, J.L.; Rabani, J. The pulse radiolysis of deaerated aqueous bromide solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1966, 70, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.; Arnhold, J.; Schwinn, J.; Sprinz, H.; Brede, O.; Arnold, K. Differences in the reactivity of phthalic hydrazide and luminol with hydroxyl radicals. Free Radic. Res. 1999, 30, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, A.N.; Hetherington, W.M., III; Baer, D.R.; Wang, L.Q.; Engelhard, M.H. Comparative SHG and XPS studies of interactions between defects and N2O on rutile (110) surfaces. Surf. Sci. 1997, 392, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, P.A.; Dobson, K.D.; McQuillan, A.J. Infrared spectroscopy of the TiO2/aqueous solution interface. Langmuir 1999, 15, 2402–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Ji, H.; Ma, W.; Zang, L.; Zhao, J. Surface modification of TiO2 by phosphate: Effect on photocatalytic activity and mechanism implication. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 5993–5600. [Google Scholar]

- Maruthamuthu, P.; Neta, P. Phosphate radicals, spectra, acid-base equilibriums, and reactions with inorganic compounds. J. Phys. Chem. 1978, 82, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusa, M.A.; Grela, M.A. Experimental upper bound on phosphate radical production in TiO2 photocatalytic transformations in the presence of phosphate ions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 3294–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lv, K.; Xiong, Z.; Leng, W.; Du, W.; Liu, D.; Xue, X. Rate enhancement and rate inhibition of phenol degradation over irradiated anatase and rutile TiO2 on the addition of NaF: New insight into the mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 19024–19032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, R.H.; Harwood, W.S.; Herring, F.G. General Chemistry, 8th ed; Pearson Prentice Hall, Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002; p. 678. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Rabani, J. The measure of TiO2 photocatalytic efficiency and the comparison of different photocatalytic titania. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 11970–11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Rabani, J.; Bahnemann, D.W.; Dohrmann, J.K. Photonic efficiency and the quantum yield of formaldehyde from methanol in the presence of various TiO2 photocatalysts. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2002, 148, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, B.M.I.; Alfano, O.M.; Cassano, A.E. Absorption and scattering coefficients of titanium dioxide particulate suspensions in water. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 20043–20050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, G.V.; Greenstock, C.L.; Helman, W.P.; Ross, A.B. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/•O−) in Aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Data 1988, 17, 513–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Mark, G.; von Sonntag, C. OH radical formation by ultrasound in aqueous solutions part I: The Chemistry underlying the terephthale dosimeter. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1996, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Selloni, A. Hydroxide ions at the water/anatase TiO2 (101) interface: Structure and electronic states from first principles molecular dynamics. Langmuir 2010, 26, 11518–11525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merenyi, G.; Lind, J.; Eriksen, T.E. Nucleophilic addition to diazaquines, formation and breakdown of tetrahedral intermediates in relation to luminol chemiluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 7716–7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, H.; Reitberger, T. Generation of Free OHaq Radicals by Black Light Illumination of Degussa (Evonik) P25 TiO2 Aqueous Suspensions. Catalysts 2013, 3, 418-443. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal3020418

Liao H, Reitberger T. Generation of Free OHaq Radicals by Black Light Illumination of Degussa (Evonik) P25 TiO2 Aqueous Suspensions. Catalysts. 2013; 3(2):418-443. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal3020418

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Haidong, and Torbjörn Reitberger. 2013. "Generation of Free OHaq Radicals by Black Light Illumination of Degussa (Evonik) P25 TiO2 Aqueous Suspensions" Catalysts 3, no. 2: 418-443. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal3020418