2.2.1. Effect of Catalyst Dosage

In photocatalytic processes, the amount of photocatalyst is an important parameter that can affect the degradation rate of organic compounds. In order to obtain the optimum catalyst dosage, the relationship between the dosage and degradation rate was investigated, as shown in

Figure 4. The results clearly show that degradation under visible light irradiation without catalysts for 160 min was negligibly small, compared with the results obtained in the presence of NaBiO

3 photocatalysts with different dosages. The smaller amount of NaBiO

3 powders exhibited a lower degradation rate, because not enough catalytic active sites were supplied during the photocatalytic process. The maximum degradation rate after 160 min was around 99% when the optimum dosage (1 g L

−1) was employed. However, the degradation rate begins to be in equilibrium if the dosage is much higher than this value.

As a comparison, the results of AO degradation over TiO

2 (P25, 1 g L

−1) under the same irradiation condition are also given in

Figure 4. The TiO

2 showed little photocatalytic activity (degradation rate less than 6%) under the visible light irradiation, because of its UV-only sensitive property [

13]. Compared to TiO

2 photocatalyst, NaBiO

3 exhibited an extremely efficient photocatalytic performance (degradation rate is over 99%) towards AO under visible light irradiation. The excellent performance could be attributed to the hybridized sp orbital in the conduction band of NaBiO

3 (Na 3s and O 2p hybridized orbits), supporting a high mobility on the sp bands for the photo-excited electrons, which may lead to suppression of the recombination of electron-hole pair and a relatively higher photocatalytic activity of the material than that of other photocatalysts [

14].

Figure 4.

Effect of NaBiO3 dosage on the photocatalytic degradation rate of acridine orange (AO). Experimental conditions: AO concentration 0.1 g L−1; pH 8.

Figure 4.

Effect of NaBiO3 dosage on the photocatalytic degradation rate of acridine orange (AO). Experimental conditions: AO concentration 0.1 g L−1; pH 8.

2.2.2. Effect of Initial pH Value and Dye Concentration

The pH value of AO solution is also a key parameter that can affect the photocatalytic process dramatically. The influence of the initial pH value on the photodegradation rate of AO dye for the NaBiO

3 suspensions is shown in

Figure 5. The results indicated that the degradation rate decreased with a decrease in pH, and it proceeded much faster under an alkaline pH. When the initial pH rose from 4.0 to 8.0, the degradation rate of AO within 160 min increased significantly from 86.7% to 99.0%. The observed increase of the degradation rate with an increase in pH can be attributed to the high hydroxylation of the photocatalyst’s surface, due to the presence of a large quantity of OH

− ions, which would facilitate the formation of much more

•OH. Since hydroxyl free radical is the dominant oxidizing species in the photocatalytic process [

17], the photodegradation of AO is therefore accelerated in an alkaline medium.

Figure 5.

Effect of pH on the photocatalytic degradation rate of AO. Experimental conditions: AO concentration 0.1 g L−1; NaBiO3 concentration 1.0 g L−1.

Figure 5.

Effect of pH on the photocatalytic degradation rate of AO. Experimental conditions: AO concentration 0.1 g L−1; NaBiO3 concentration 1.0 g L−1.

By varying the initial dye concentration from 0.05 to 0.20 g L

−1 at constant NaBiO

3 dosage (1.0 g L

−1, pH 8), its effect on the degradation rate could be determined, and the results are shown in

Figure 6. As seen in the figure, degradation efficiency is inversely affected by the dye concentration. This negative effect can be explained as follows: as the dye concentration is increased, the equilibrium adsorption of dye on the catalyst surface active sites increases; hence, competitive adsorption of OH

− on the same sites decreases, meaning a lower formation rate of

•OH radical, which is the principal oxidant necessary for a high degradation efficiency. On the other hand, considering the Beer-Lambert law, as the initial dye concentration increases, the path length of photons entering the solution decreases, resulting in lower photon absorption on catalyst particles and, consequently, a lower photodegradation rate.

Figure 6.

Effect of initial dye concentration on the photocatalytic degradation rate of AO. Experimental conditions: NaBiO3 concentration 1.0 g L−1; pH 8.

Figure 6.

Effect of initial dye concentration on the photocatalytic degradation rate of AO. Experimental conditions: NaBiO3 concentration 1.0 g L−1; pH 8.

2.2.3. Effects of Anions

The study of the effects of anions on the photocatalytic degradation of AO is important, because anions are rather common in natural water and industrial wastewater. The effects of the presence of various anions, such as chloride, bicarbonate and carbonate, were studied using 0.05 M solutions of their sodium salts and an initial concentration of 0.1 g L

−1 of AO with a 1 g L

−1 of NaBiO

3. The results showed that all these anions inhibit the degradation significantly (see

Figure 7). To investigate the effects of variations of the concentration of anions on the degradation rate of AO, chloride and bicarbonate were also added at a different concentration (0.1 M) in the initial solution. It can be seen that the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of AO decreases further with increasing the concentration of anions. Inhibition effects of anions can be explained as the reaction of hydroxyl radical with anions that behaved as

•OH radical scavengers (Equations (1)–(3)) resulting in prolonged AO removal. Formation of inorganic radical anions (e.g., Cl

•, CO

3•−) under these circumstances is possible.

However, these radicals have a lower oxidation potential than hydroxyl radicals (

E0(CO

3•−/CO

32−) = 1.85 V,

E0(Cl

•/Cl

−) = 2.47 V,

E0(OH

•/H

2O) = 2.80 V); they are not as reactive as

•OH, and thus the rate of photocatalytic degradation is reduced [

18,

19,

20].

2.2.4. Evolution of Total Organic Carbon (TOC)

The complete degradation of an organic molecule by photocatalysis normally leads to the conversion of all its carbon atoms to gaseous CO

2 and of the heteroatoms into inorganic anions that remain in solution. In order to study the total mineralization of AO, the determination of total organic carbon (TOC) was carried out as a function of the irradiation time. The decrease in the TOC percentage of AO during the photocatalytic degradation is depicted in

Figure 8. The complete removal of AO (0.1 g L

−1) was achieved after 160 min of treatment, and the corresponding carbon mineralization was 44%. The treatment was prolonged to 16 h to test whether mineralization could be completed, as well. Approximately 77% of AO was mineralized within 16 h of the photocatalytic reaction time. Complete mineralization of AO was not achieved after 16 h of oxidation, although AO disappeared after 160 min. The great difference between degradation efficiency and mineralization efficiency implied that the products of AO oxidation mostly stayed at the intermediate product stage under the present experimental conditions.

Figure 7.

Effect of anions on the photocatalytic degradation rate of AO. Experimental conditions: AO concentration 0.1 g L−1; NaBiO3 concentration 1.0 g L−1; pH 8.

Figure 7.

Effect of anions on the photocatalytic degradation rate of AO. Experimental conditions: AO concentration 0.1 g L−1; NaBiO3 concentration 1.0 g L−1; pH 8.

Figure 8.

Depletion in total organic carbon (TOC) measured as a function of irradiation time for an aqueous solution of AO (0.1 g L−1) in the presence of NaBiO3 (1.0 g L−1).

Figure 8.

Depletion in total organic carbon (TOC) measured as a function of irradiation time for an aqueous solution of AO (0.1 g L−1) in the presence of NaBiO3 (1.0 g L−1).

2.2.5. Separation and Identification of the Intermediates

Analyses of the intermediates would help to better comprehend the details of the reaction process. Because of the spectral overlap between the original dye and its degradation intermediates, temporal variations during the photooxidation of AO were monitored by HPLC equipped with a UV-visible diode array detector. The chromatogram recorded at 492 nm is shown in

Figure 9. With irradiation up to 120 min, six components were identified, all with retention times less than 34 min. We denoted the AO dye and its related intermediates as species

A–F. Except for the initial AO dye (peak

A), the intensities of the other peaks increased at first and, subsequently, decreased, indicating the formation and transformation of the intermediates.

Figure 9.

HPLC chromatogram obtained for AO solution after 120 min of irradiation with visible light in the presence of NaBiO3.

Figure 9.

HPLC chromatogram obtained for AO solution after 120 min of irradiation with visible light in the presence of NaBiO3.

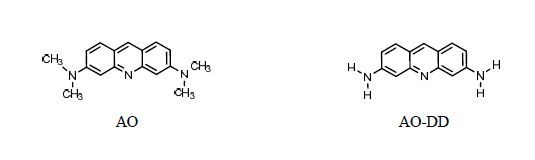

The absorption spectra of each intermediate in the visible spectral region are depicted in

Figure 10. The absorption maximum of the spectral bands shifts hypsochromically from 491.6 nm (

Figure 10, spectrum

A) to 451.4 nm (

Figure 10, Spectrum

F). This hypsochromic shift of the absorption band was presumed to result from the stepwise formation of a series of

N-de-methylated intermediates (

i.e., methyl groups were removed one by one, as confirmed by the gradual peak wavelength shifts toward the blue region). Considering the auxochromic property of the

N-methyl group, the characteristic absorption of the intermediate with less

N-methyl was expected to occur at a shorter wavelength [

21]. Similar phenomena were also observed during the photodegradation of Rhodamine-B over NaBiO

3 under visible irradiation [

15].

Figure 10.

Absorption spectra of the N-de-methylated intermediates formed during the photocatalytic degradation process of the AO.

Figure 10.

Absorption spectra of the N-de-methylated intermediates formed during the photocatalytic degradation process of the AO.

The

N-de-methylated intermediates were further confirmed using the HPLC-ESI-MS method (

Figure 11). The molecular ion peaks appeared to be in the acid forms of the intermediates.

Table 1 presents the absorption maximum and the mass peaks of the

N-de-methylated intermediates and the corresponding compounds identified by interpretation of their mass spectra. From the results of mass spectral analysis, we confirmed that the component

A,

m/

z = 266.18, in liquid chromatogram was AO. The other components were

B,

m/

z = 252.07,

N-de-mono-methyl-acridine orange;

C,

m/

z = 238.01,

N,

N’-de-dimethyl-acridine orange;

D,

m/

z = 238.14,

N,

N-de-dimethyl-acridine orange;

E,

m/

z = 224.03,

N,

N,

N′-de-trimethyl-acridine orange; and

F,

m/

z = 210.04,

N,

N,

N’,

N’

,-de-tetramethyl-acridine orange. These peaks differ exactly by 14 mass units successively, which consist of the sequential

N-de-methylation of maternal AO. The proposed

N-tetra-de-methylated intermediate (AO-DD) has been compared with the standard material of 3,6-diaminoacridine. The retention times and absorption spectra are identical.

Figure 11.

ESI mass spectra of the N-de-methylated intermediates formed during the photodegradation of the AO dye after they were separated by the HPLC-ESI-MS method.

Figure 11.

ESI mass spectra of the N-de-methylated intermediates formed during the photodegradation of the AO dye after they were separated by the HPLC-ESI-MS method.

Table 1.

Identification of the N-de-methylation intermediates of the AO dye by HPLC-ESI-MS.

It is relevant to note that when the solution was monitored at the m/z = 238 mode, two peaks (C and D) appeared in the ion chromatogram. Both of them were regarded to be the intermediates that possess two less methyl groups relative to the AO dye. One of the isomers lost two methyl groups at the same side of AO, noted as AO-D; the other one, formed by removal of a methyl group from each side of the AO molecule, noted as AO-MM. Considering that the polarity of the AO-D species is greater than that of the AO-MM intermediate, we expected the latter to be eluted off the LC column after the AO-D species. As well, to the extent that two N-methyl groups are stronger auxochromic moieties than the N,N-dimethyl or amino groups are, the maximal absorption of the AO-D intermediate was anticipated to occur at a wavelength shorter than the band position of the AO-MM species.

The relative distribution of the

N-de-methylated intermediates obtained is illustrated in

Figure 12. To minimize errors, the relative intensities were recorded at the maximum absorption wavelength for each intermediate, although a quantitative determination of all of the photogenerated intermediates was not achieved, owing to the lack of the appropriate molar extinction coefficients of these intermediates and the related reference standards. Nonetheless, we clearly observed the changes in the distribution of each intermediate during the photodegradation process of the AO dye. The first product (AO-M) of

N-de-methylation reached its maximum concentration after a 20 min irradiation period (

Figure 12, curve B). Considering that the

N,

N-dimethyl group in AO-M is bulkier than the

N-methyl group in AO-M molecules, the attack of

•OH radicals on the

N-methyl groups should be favored at the expense of the

N,

N-dimethyl groups. In accord with this notion, the HPLC results showed that the AO-D intermediate reached maximal concentration before the AO-MM intermediate did. The

N-di-de-methylated intermediates (AO-MM and AO-D) were observed (

Figure 12, curve C–D) to reach their maximum concentrations after 60 and 40 min irradiation periods, respectively. The

N-tri-de-methylated intermediate (AO-DM) was observed (

Figure 12, curve E) to reach its maximum concentration after a 80 min irradiation period, because the

•OH attacked the

N-methyl groups of AO-MM and the

N,

N-dimethyl group of AO-D. The successive appearance of the maximal quantity of each intermediate indicates that the

N-de-methylation of AO is a stepwise photochemical process.

Figure 12.

Variation in the relative distribution of the

N-de-methylated products obtained from the photodegradation of the AO dye as a function of the irradiation time. Curves B–F correspond to the peaks B–F in

Figure 9, respectively.

Figure 12.

Variation in the relative distribution of the

N-de-methylated products obtained from the photodegradation of the AO dye as a function of the irradiation time. Curves B–F correspond to the peaks B–F in

Figure 9, respectively.

2.2.6. Degradation Pathway of AO

Photocatalytic processes use light to generate conduction band electrons and valence band holes (e

− and h

+) capable of initiating redox chemical reactions on semiconductors. Previous studies indicated that the large dispersion of the hybridized sp orbitals in the conduction band of NaBiO

3 increases the mobility of the photoexcited electrons, thus suppressing the recombination of photoexcited electron-hole pairs [

14]. The hole photogenerated on the surface of NaBiO

3 could easily react with OH

−/H

2O to form ·

•OH [

13]. The

N-de-methylation of the AO occurs mostly by the attack of the

•OH species on the

N,

N-dimethyl groups of the AO, as shown in

Scheme 1. Therefore,

N-de-methylation seems play an important role in the degradation of AO. However, in our separate study, to further explore other possible degradation pathway of AO, photocatalysis in NaBiO

3 slurries (1.0 g L

−1) was conducted with a starting solution of 3,6-diaminoacridine (compound

F, AO-DD). The results showed that AO-DD indeed underwent degradation. Unfortunately, none of its degradation by-products were found and identified at this time. It was suspected that degradation followed by the chromophore rupture path might be also possible.

Scheme 1.

Proposed photodegradation mechanism of the AO dye under visible light irradiation in aqueous NaBiO3 dispersions, followed by the identification of several intermediates by HPLC-ESI mass spectral techniques.

Scheme 1.

Proposed photodegradation mechanism of the AO dye under visible light irradiation in aqueous NaBiO3 dispersions, followed by the identification of several intermediates by HPLC-ESI mass spectral techniques.

Hydroxyl radicals yield carbon-centered radicals upon the H-atom abstraction from the methyl group or they react with the lone-pair electron on the N atom to generate cationic radicals, which subsequently convert into carbon-centered radicals [

22]. The carbon-centered radicals react rapidly with O

2 to produce peroxy radicals that subsequently transform into alkoxy radicals through the bimolecular Russell mechanism [

23]. The fragmentation of the alkoxy radical produces a de-methylated product. The mono-de-methylated species, AO-M, can also be attacked by

•OH species and be implicated in other similar events (H-atom abstraction, oxygen attack and the bimolecular Russell mechanism) to yield the bi-de-methylated intermediates, AO-MM and AO-D. The

N-de-methylation process, as described above, continues until formation of the completely

N-de-methylated species, AO-DD.