Interface-Active Metal Organic Frameworks for Knoevenagel Condensations in Water

Abstract

:1. Introduction

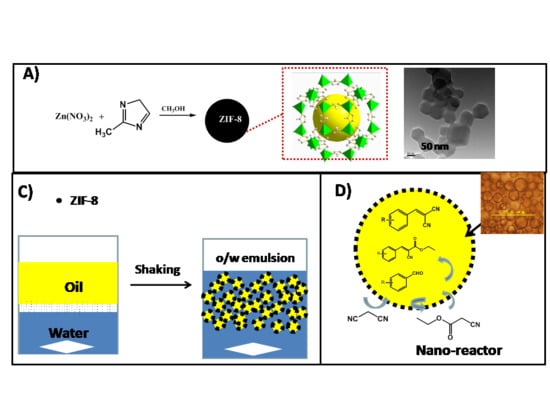

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Preparation of ZIF-8 Nanoparticles

3.2. Characterization

3.3. Catalytic Activity Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pera-Titus, M.; Leclercq, L.; Clacens, J.M.; Campo, F.; Nardello-Rataj, V. Pickering Interfacial Catalysis for Biphasic Systems: From Emulsion Design to Green Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2006–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.J.; Fang, L.; Fan, Z.Y.; Albela, B.; Bonneviot, L.; De Campo, F.; Pera-Titus, M.; Clacens, J.M. Tunable Catalysts for Solvent-Free Biphasic Systems: Pickering Interfacial Catalysts over Amphiphilic Silica Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4869–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.Q.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, W.J. A Strategy for Separating and Recycling Solid Catalysts Based on the pH-Triggered Pickering-Emulsion Inversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7455–7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.Y.; Wei, L.J.; Jing, L.Y.; Liang, J.F.; Zhang, X.M.; Tang, M.; Monteiro, M.J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, S.; et al. Dumbbell-Shaped Bi-component Mesoporous Janus Solid Nanoparticles for Biphasic Interface Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8459–8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rong, X.; Yang, H.Q.; Zhao, N. Rationally Turning the Interface Activity of Mesoporous Silicas for Preparing Pickering Foam and “Dry Water”. Langmuir 2017, 33, 9025–9033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.W.; Zhou, L.; Bing, W.; Zhang, Z.J.; Li, Z.H.; Ren, J.S.; Qu, X.G. Light Controlled Reversible Inversion of Nanophosphor-Stabilized Pickering Emulsions for Biphasic Enantioselective Biocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7498–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, W.; Yang, H.Q.; Du, Z.P. Synthesis of pH-Responsive Inorganic Janus Nanoparticles and Experimental Investigation of the Stability of Their Pickering Emulsions. Langmuir 2017, 33, 10283–10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Cho, J.; Cho, J.; Park, B.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, K.H.; Kim, J.W. Synthesis of Monodisperse Bi-Compartmentalized Amphiphilic Janus Microparticles for Tailored Assembly at the Oil-Water Interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4509–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata, P.A.; Faria, J.; Ruiz, M.P.; Jentoft, R.E.; Resasco, D.E. Hydrophobic Zeolites for Biofuel Upgrading Reactions at the Liquid-Liquid Interface in Water/Oil Emulsions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8570–8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossley, S.; Faria, J.; Shen, M.; Resasco, D.E. Solid Nanoparticles that Catalyze Biofuel Upgrade Reactions at the Water/Oil Interface. Science 2010, 327, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.H.; Wang, J.C.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.A.; Dong, Y.B. CuI@UiO-67-IM: A MOF-Based Bifunctional Composite TriphaseTransfer Catalyst for Sequential One-Pot Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition in Water. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 8341–8347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, J.; Marcello, M.; Garai, A.; Bradshaw, D. MOF-Polymer Composite Microcapsules Derived from Pickering Emulsions. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2717–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha, O.K.; Hupp, J.T. Rational Design, Synthesis, Purification, and Activation of Metal Organic Framework Materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, J.; Aguilera-Sigalat, J.; El-Hankari, S.; Bradshaw, D. Magnetic MOF Microreactors for Recyclable Size-selective Biocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1938–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.H.; Liu, X.L.; Demir, N.K.; Chen, J.P.; Li, K. Applications of water stable metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5107–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtch, N.C.; Jasuja, H.; Walton, K.S. Water stability and adsorption in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10575–10612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schejn, A.; Mazet, T.; Falk, V.; Balan, L.; Aranda, L.; Medjahdi, G.; Schneider, R. Fe3O4@ZIF-8: Magnetically recoverable catalysts by loading Fe3O4 nanoparticles inside a zinc imidazolate framework. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 10136–10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebbat, N.; Commenge, J.M.; Medjandi, G.; Schneider, R. ZIF-8 nanoparticles as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the Knoevenagel synthesis of cyanoacrylates and 3-cyanocoumarins. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 5885–5888. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.B.; Shi, J.J.; Xia, M.; Zhang, J.; Pang, Z.F.; Marchetti, A.; Wang, X.H.; Cai, J.S.; Kong, X.Q. Monodispersed ZIF-8 particles with enhanced performance for CO2 adsorption and heterogeneous catalysis. Appl Surf. Sci. 2017, 423, 349–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.L.; Ky, L.E.; Phan, N.T.S. A Zeolite Imidazolate Framework ZIF-8 Catalyst for Friedel-Crafts Acylation. Chin. J. Catal. 2012, 33, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.W.; Langner, E.H.G. The effect of synthesis temperature on the particle size of nano-ZIF-8. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 221, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Zhang, J.; Tian, M.M.; Quan, C.S.; Fan, S.D. Fabrication of Amino-functionalized Fe3O4@Cu3(BTC)2 for Heterogeneous Knoevenagel Condensation. Chin. J. Catal. 2016, 37, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Dai, T.L.; Zhang, J.; Chu, G.; Quan, C.S. Fe3O4@UiO-66-NH2 Core-Shell Nanohybrid as Stable Heterogeneous Catalyst for Knoevenagel Condensation. Chin. J. Catal. 2016, 37, 2106–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.Z.; Aranishi, K.; Xu, Q. ZIF-8 immobilized nickel nanoparticles: Highly effective catalysts for hydrogen generation from hydrolysis of ammonia borane. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 3173–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.Y.; Sun, C.Y.; Qin, C.; Wang, X.L.; Yang, G.S.; Shao, K.Z.; Lan, Y.Q.; Su, Z.M.; Huang, P.; Wang, C.G.; et al. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 as efficient pH-sensitive drug delivery vehicle. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 6906–6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Catalyst | Solvent | Time (min) | Yield (%) | Catalyst | Solvent | Time (min) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| ZIF-8 | Water | 30 | 82 | ZIF-8 | DMF | 30 | 97 |

| THF | 30 | 65 | Ethyl acetate | 30 | 49 | ||

| Hexane | 30 | 7 | Toluene | 30 | 32 | ||

| Ethanol | 30 | 82 | DMSO | 30 | 92 | ||

| Entry | Catalyst | Substrate | Substrate | Time (min) | T (°C) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blank |  |  | 30(60) | 80 | <2(3) |

| 2 | ZIF-8 |  |  | 30(60) | 80 | 82(>99) |

| 3 |  |  | 10(30) | 80 | 91(>99) | |

| 4 |  |  | 10(30) | 40 | 51(95) | |

| 5 |  |  | 10(30) | 40 | 10(36) | |

| 6 |  |  | 30(60) | 80 | 27(79) | |

| 7 |  |  | 60 | 80 | 45 | |

| 8 |  |  | 120 | 80 | 23 | |

| 9 |  |  | 10 | 40 | 85 | |

| 10 |  |  | 10 | 40 | 98 | |

| 11 |  |  | 10 | 40 | 98 | |

| 12 |  |  | 15 | 40 | 47 | |

| 13 |  |  | 30 | 40 | 12 | |

| 14 | Blank |  |  | 30 | 40 | 18 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bai, R.; Hou, X.; Li, J. Interface-Active Metal Organic Frameworks for Knoevenagel Condensations in Water. Catalysts 2018, 8, 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8080315

Zhang Y, Zhang X, Bai R, Hou X, Li J. Interface-Active Metal Organic Frameworks for Knoevenagel Condensations in Water. Catalysts. 2018; 8(8):315. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8080315

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yanmei, Xiang Zhang, Rixia Bai, Xiyan Hou, and Jun Li. 2018. "Interface-Active Metal Organic Frameworks for Knoevenagel Condensations in Water" Catalysts 8, no. 8: 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8080315

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhang, X., Bai, R., Hou, X., & Li, J. (2018). Interface-Active Metal Organic Frameworks for Knoevenagel Condensations in Water. Catalysts, 8(8), 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8080315