Preparation and Characterisation of Poly(methyl metacrylate)-Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposites for Denture Bases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods of NP Characterisation

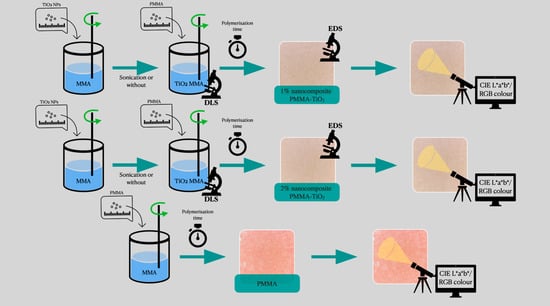

2.3. Preparation of Poly(methyl methacrylate) Modified with TiO2 Nanoparticles

2.4. Measurement of Initial Polymerisation Time of Modified PMMA

2.5. Comparison of Colour of Modified and Unmodified PMMA

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Nanoparticles

3.2. EDS Analysis

3.3. Initial Polymerisation Time of Modified PMMA

3.4. Comparison of Colour of Modified and Unmodified PMMA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The presence of TiO2 nanoparticles sized below 100 nm was indicated in the structure of the newly created biomaterial, which constitutes a ground for calling it a nanocomposite.

- There is no justification for the use of ultrasonic cleaners in the procedure of TiO2 nanoparticles incorporation into PMMA.

- The reduced polymerisation time of the new biomaterial fully enables the performance of standard procedures related to the creation of denture bases.

- Due to the considerable change in the colour, the clinical application is limited to the performance of repairs or relining of the prosthesis, where the new material is located in an area with no aesthetic requirements (impression surface or not exposed polished surface of the denture base).

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spiechowicz, E.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. Oral Cavity Candidiasis, 1st ed.; Med Tour Press International: Otwock, Poland, 1998; ISBN 83-903590-9-X. [Google Scholar]

- Uzunoglu, E.; Zeynep, A.; Bicer, E.; Dolapci, I.; Dogan, A. Biofilm-forming ability and adherence to poly-(methyl-methacrylate) acrylic resin materials of oral Candida albicans strains isolated from HIV positive subjects. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2014, 6, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cierech, M.; Szczypińska, A.; Wróbel, K.; Gołaś, M.; Walke, W.; Pochrząst, M.; Przybyłowska, D.; Bielas, W. Comparative analysis of the roughness of acrylic resin materials used in the process of making the bases of dentures and investigation of adhesion of Candida albicans to them. In vitro study. Dent. Med. Probl. 2013, 50, 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Makvandi, P.; Gu, J.T.; Zare, E.N.; Ashtari, B.; Moeini, A.; Tay, F.R.; Niu, L.N. Polymeric and inorganic nanoscopical antimicrobial fillers in dentistry. Acta. Biomater. 2020, 101, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gad, M.M.; Fouda, S.M.; Al-Harbi, F.A.; Näpänkangas, R.; Raustia, A. PMMA denture base material enhancement: A review of fiber, filler, and nanofiller addition. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 3801–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.M.; Abualsaud, R. Behavior of PMMA Denture Base Materials Containing Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: A Literature Review. Int. J. Biomater. 2019, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierech, M.; Kolenda, A.; Grudniak, A.M.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Woźniak, B.; Gołaś, M.; Swoboda-Kopeć, E.; Łojkowski, W.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. Significance of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) modification by zinc oxide nanoparticles for fungal biofilm formation. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 510, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierech, M.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Szmigiel, D.; Bączkowski, B.; Grudniak, A.; Wolska, K.; Łojkowski, W.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. Preparation and characterization of ZnO-PMMA resin nanocomposites for denture bases. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2016, 18, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierech, M.; Osica, I.; Kolenda, A.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Szmigiel, D.; Łojkowski, W.; Kurzydłowski, K.; Ariga, K.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. Mechanical and physicochemical properties of newly formed ZnO-PMMA nanocomposites for denture bases. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierech, M.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Kolenda, A.; Krawczyk-Balska, A.; Prochwicz, E.; Woźniak, B.; Łojkowski, W.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. Zinc oxide nanoparticles cytotoxicity and release from newly formed PMMA–ZnO nanocomposites designed for denture bases. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Torres, L.S.; López-Marín, L.M.; Núñez-Anita, R.E.; Hernández-Padrón, G.; Castaño, V.M. Biocompatible metal-oxide nanoparticles: Nanotechnology improvement of conventional prosthetic acrylic resins. J. Nanomater. 2011, 2011, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrowiecki, R.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Zareba, T.; Koltsov, I.; Lojkowski, W.; Tyski, S.; Mielczarek, A.; Zawadzki, P. Nanoparticles and human saliva: A step towards drug delivery systems for dental and craniofacial biomaterials. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9235–9257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cierech, M.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Kolenda, A.; Łojkowski, W.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E.; Zawadzki, P. Charakterystyka nanotlenku tytanu (IV) jako potencjalnego modyfikatora polimetakrylanu metylu. Prosthodontics 2017, 67, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karci, M.; Demir, N.; Yazman, S. Evaluation of Flexural Strength of Different Denture Base Materials Reinforced with Different Nanoparticles. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwander, M.; Rosentritt, M.; Schneider-Feyrer, S.; Hahnel, S. Biofilm formation on denture base resin including ZnO, CaO, and TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polish Center for Accreditation, Testing Laboratories, Accreditation Number: AB 1503. Available online: https://www.pca.gov.pl/en/accredited-organizations/accredited-organizations/testing-laboratories/AB%201503,entity.html (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Wojnarowicz, J.; Chudoba, T.; Gierlotka, S.; Lojkowski, W. Effect of Microwave Radiation Power on the Size of Aggregates of ZnO NPs Prepared Using Microwave Solvothermal Synthesis. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarowicz, J.; Opalinska, A.; Chudoba, T.; Gierlotka, S.; Mukhovskyi, R.; Pietrzykowska, E.; Sobczak, K.; Lojkowski, W. Effect of water content in ethylene glycol solvent on the size of ZnO nanoparticles prepared using microwave solvothermal synthesis. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 2789871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanopowder XRD Processor Demo. Available online: http://science24.com/xrd/ (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Schellenberg, J.; Otto, T.; Schadewald, A. Processing Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Autopolymerizing Hypoallergenic Denture Base Polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 41378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiato, M.C.; Dos Santos, D.M.; Baptista, G.T.; Moreno, A.; Andreotti, A.M.; Bannwart, L.C.; Dekon, S.F. Effect of thermal cycling and disinfection on colour stability of denture base acrylic resin. Gerodontology 2013, 30, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, D.; Deng, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Yang, B.; Luo, D.; Zhang, D.; Kuang, H. Gestational exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles impairs the placentation through dysregulation of vascularization, proliferation and apoptosis in mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Properties of Sample TiO2 NPs (Anatase) Catalog Number: 637254. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/aldrich/637254?lang=en®ion=NL (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Noman, M.T.; Ashraf, M.A.; Ali, A. Synthesis and applications of nano-TiO2: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 3262–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamukamba, P.; Okoh, O.; Mungondori, H.; Taziwa, R.; Zinya, S. Synthetic Methods for Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: A Review; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2018; p. 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicari, T.; Dagostim, A.C.; Klingelfus, T.; Galvan, G.L.; Monteiro, P.S.; da Silva Pereira, L.; de Assis, H.C.S.; Cestaria, M.M. Co-exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles (NpTiO2) and lead at environmentally relevant concentrations in the Neotropical fish species Hoplias intermedius. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 1032–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorenz, R.; Bellardita, M.; Scirè, S.; Palmisano, L. Photocatalytic H2 production over inverse opal TiO2 catalysts. Catal. Today 2019, 321–322, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, N.H.; Ali, A.M.; Yaseen, K.H. The evaluation effect of TiO2 nano particles on different bacterial strains isolated from water purification stations in Baghdad. J. Sci. 2016, 57, 2378–2385. [Google Scholar]

- Wojnarowicz, J.; Chudoba, T.; Lojkowski, W. A Review of Microwave Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanomaterials: Reactants, Process Parameters and Morphologies. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manerat, C.; Hayata, Y. Antifungal activity of TiO2 photocatalysis against Penicillium expansum in vitro and in fruit tests. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 107, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, D.A.; McGuigan, K.G.; Ibáñez, P.F.; Polo-López, M.I.; Byrne, J.A.; Dunlop, P.S.M.; O’Shea, K.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Pillai, S.C. Solar photocatalysis for water disinfection: Materials and reactor design. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 1211–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Liu, X.; Xie, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, C. Antibacterial Activity of Visible Light-Activated TiO2 Thin Films with Low Level of Fe Doping. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5819805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Sakai, T.; Moroi, R.; Nakagawa, M.; Sakai, H.; Ogata, T.; Terada, Y. Self-cleaning ability of a photocatalyst-containing denture base material. Dent. Mater. J. 2008, 27, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, M.; Ueda, T.; Sawaki, K.; Kawaguchi, M.; Sakurai, K. Biocompatibility of a titanium dioxide-coating method for denture base acrylic resin. Gerodontology 2016, 33, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.K. TiO2-Nanofillers Effects on Some Properties of Highly- Impact Resin Using Different Processing Techniques. Open. Dent. J. 2018, 12, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. Properties improvement of PMMA using nano TiO2. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 118, 2890–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehifard, E.; Robati Anaraki, M.; Shirkavand, S. Effect of adding TiO2 nanoparticles on the SEM morphology and mechanical properties of conventional heat-cured acrylic resin. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2019, 13, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrahlah, A.; Fouad, H.; Hashem, M.; Niazy, A.A.; AlBadah, A. Titanium Oxide (TiO(2))/Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Denture Base Nanocomposites: Mechanical, Viscoelastic and Antibacterial Behavior. Materials 2018, 11, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirkavand, S.; Moslehifard, E. Effect of TiO2 Nanoparticles on Tensile Strength of Dental Acrylic Resins. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospects 2014, 8, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracane, J.L. Hygroscopic and hydrolytic effects in dental polymer networks. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazirkar, G.; Bhanushali, S.; Singh, S.; Pattanaik, B.; Raj, N. Effect of anatasetitanium dioxide nanoparticles on the flexural strength of heat cured poly-methylmethacrylate resins: An in-vitro study. J. Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2014, 14, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandra, E.; Wahyuningtyas, E.; Sugiatno, E. The effect of nanoparticles TiO2 on the flexural strength of acrylic resin denture plate. Padjadjaran J. Dent. 2018, 30, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodagar, A.; Bahador, A.; Khalil, S.; Shahroudi, A.S.; Kassaee, M.Z. The effect of TiO2 and SiO2 nanoparticles on flexural strength of poly(methyl methacrylate) acrylic resins. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2013, 57, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Hamada, N.; Kimoto, K.; Sawada, T.; Sawada, T.; Kumada, H. Antifungal effect of acrylic resin containing apatite-coated TiO2 photocatalyst. Dent. Mater. J. 2007, 26, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, S.A.; Al-Ameer, S.S. The effect of the addition of silanized Nano titania fillers on some physical and mechanical properties of heat cured acrylic denture base materials. J. Baghdad Coll. Dent. 2015, 27, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, S.H.; Keyf, F.; Gumus, H.O.; Uzun, C. The evaluation of water sorption/solubility on various acrylic resins. Eur. J. Dent. 2008, 2, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Composition | PMMA (Control Group) | 1% Nanocomposite | 2% Nanocomposite |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 NPs powder | 0 g | 0.32 g | 0.64 g |

| PMMA powder polymer | 22 g | 22 g | 22 g |

| Liquid monomer of PMMA | 10 g | 10 g | 10 g |

| Group | Group Designation | Number of Trials | TiO2 NPs Content | Manual Mixing | Use of Ultrasounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (control group) | 0% | 4 | 0% | Yes | No |

| 1 | 0%S | 4 | 0% | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | 1% | 4 | 1% | Yes | No |

| 3 | 1%S | 4 | 1% | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | 2% | 4 | 2% | Yes | No |

| 5 | 2%S | 4 | 2% | Yes | Yes |

| Sample | Specific Surface Area, as (m2/g) | Skeleton Density, ρs ± σ (g/cm3) | Average Particle Size from SSA BET, d ± σ (nm) | Average Crystallite Size from Nanopowder XRD Processor Demo, d ± σ (nm) | Average Crystallite Size, Scherrer’s Formula, d ± σ (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 NPs | 81.6 | 3.68 ± 0.01 | 20 ± 1 | 30 ± 8 | 32 ± 20 |

| Sample TiO2 NPs/MMA | Size by DLS, Z-Average, d ± σ (nm) | Polydispersity Index, Pdl |

|---|---|---|

| Mixing for 1 min | 3589 ± 914 | 0.349 ± 0.052 |

| Mixing for 1 min and ultrasonic mixing for 240 s and ultrasonic mixing for 60 s | 4080 ± 567 | 0.562 ± 0.227 |

| Group | Trial | Initial Polymerisation Time (s) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (0%) | 1 | 400 | 409.25 | 6.5 |

| 2 | 410 | |||

| 3 | 415 (highest) | |||

| 4 | 412 | |||

| 1 (0% + S) | 1 | 375 | 369.5 | 4.20 |

| 2 | 370 | |||

| 3 | 410 | |||

| 4 | 390 | |||

| 2 (1%) | 1 | 375 | 367.0 | 7.26 |

| 2 | 370 | |||

| 3 | 358 | |||

| 4 | 365 | |||

| 3 (1%S) | 1 | 245 (lowest) | 249.75 | 5.50 |

| 2 | 255 | |||

| 3 | 245 (lowest) | |||

| 4 | 254 | |||

| 4 (2%) | 1 | 340 | 349.25 | 6.50 |

| 2 | 350 | |||

| 3 | 355 | |||

| 4 | 352 | |||

| 5 (2%S) | 1 | 260 | 257.5 | 10.41 |

| 2 | 255 | |||

| 3 | 270 | |||

| 4 | 245 (lowest) |

| Group | Measurement | CIE L*a*b* Colour Model | RGB Colour Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (0% TiO2 NPs) | 1 | L 44.13 a 9.92 b 3.62 | 123.98.99 |

| 2 | L 44.64 a 9.98 b 3.69 | 124.100.100 | |

| 3 | L 44.36 a 10.02 b 3.30 | 124.99.100 | |

| 2 (1% TiO2 NPs) | 1 | L 66.98 a 10.90 b 14.29 | 192.155.138 |

| 2 | L 65.14 a 10.69 b 12.46 | 185.151.136 | |

| 3 | L 66.67 a 10.99 b 14.15 | 191.155.137 | |

| 4 (2% TiO2 NPs) | 1 | L 67.68 a 10.75 b 12.64 | 193.158.143 |

| 2 | L 65.60 a 10.59 b 13.25 | 187.152.136 | |

| 3 | L 66.54 a 10.49 b 12.42 | 189.155.140 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cierech, M.; Szerszeń, M.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Łojkowski, W.; Kostrzewa-Janicka, J.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. Preparation and Characterisation of Poly(methyl metacrylate)-Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposites for Denture Bases. Polymers 2020, 12, 2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12112655

Cierech M, Szerszeń M, Wojnarowicz J, Łojkowski W, Kostrzewa-Janicka J, Mierzwińska-Nastalska E. Preparation and Characterisation of Poly(methyl metacrylate)-Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposites for Denture Bases. Polymers. 2020; 12(11):2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12112655

Chicago/Turabian StyleCierech, Mariusz, Marcin Szerszeń, Jacek Wojnarowicz, Witold Łojkowski, Jolanta Kostrzewa-Janicka, and Elżbieta Mierzwińska-Nastalska. 2020. "Preparation and Characterisation of Poly(methyl metacrylate)-Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposites for Denture Bases" Polymers 12, no. 11: 2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12112655

APA StyleCierech, M., Szerszeń, M., Wojnarowicz, J., Łojkowski, W., Kostrzewa-Janicka, J., & Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. (2020). Preparation and Characterisation of Poly(methyl metacrylate)-Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposites for Denture Bases. Polymers, 12(11), 2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12112655